Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

|

Diseases of Gastrointestinal System and Liver |

||

Table 11.1: Causes of vomiting |

or photophobia. These patients need immediate |

||

Gastrointestinal |

Nongastrointestinal |

investigation in a hospital. |

|

Workup for chronic vomiting should include evaluation |

|||

|

|

||

Acute |

|

for cause with blood chemistry (blood sugar, electrolytes, |

|

|

|

||

Gastroenteritis |

Infections, e.g. urinary tract |

serum amylase and liver enzymes); ultrasound abdomen, |

|

Hepatitis |

infection, meningitis, ence |

upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and, as indicated by |

|

Appendicitis |

phalitis, pertussis |

available clues, barium studies (meal and small bowel |

|

Small intestinal obstruction, |

Raised intracranial tension |

follow-through), gastric emptying scan, CT or MRI brain, |

|

(malrotation, volvulus, |

Diabetic ketoacidosis |

metabolic testing or urine analysis. It is important to |

|

intussusception) |

Defects in fatty acid oxidation |

||

remember that children with cyclic vomiting should be |

|||

Cholecystitis |

or respiratory chain |

||

evaluated during symptomatic attack before starting |

|||

Pancreatitis |

Drug or toxin induced |

||

intravenous fluids since test results are typically non |

|||

|

|

||

Chronic |

|

contributory during asymptomatic periods. |

|

|

|

||

Gastroesophageal reflux |

Raised intracranial tension |

Evaluation of a child with acute vomiting should |

|

include assessment of hydration, electrolytes, creatinine |

|||

Gastritis |

Chronic sinusitis |

||

Gastric outlet obstruction |

Uremia |

and plain X-ray abdomen (in suspected surgical causes). |

|

(hypertrophic pyloric |

Overfeeding |

Promethazine andondansetron are usefulin postoperative |

|

stenosis, peptic ulcer) |

|

vomiting and to abort episodes of cyclical vomiting. |

|

Small bowel obstruction |

|

Ondansetron, given alone or with dexamethasone, is |

|

(duodenal stenosis, annular |

|

preferred for chemotherapy related vomiting. Domperi |

|

pancreas, superior |

|

done and metoclopramide are useful in patients with |

|

mesenteric artery syndrome) |

|

||

|

gastroparesis.Antihistaminicslikediphenhydraminehelp |

||

Food allergy |

|

||

|

in motion sickness. Management of the underlying |

||

Achalasia cardia |

|

||

|

condition is essential. |

||

Gastroparesis |

|

||

|

Some common disorders presenting with vomiting are |

||

Eosinophilic esophagitis |

|

||

|

described below: |

||

Recurrent |

|

||

|

|

||

Cyclic vomiting |

Urea cycle defects |

Idiopathic Hypertrophlc Pyloric Stenosls |

|

Abdominal migraine |

Diabetic ketoacidosis |

Hypertrophicpyloricstenosisisthe mostcommonsurgical |

|

Malrotation with volvulus |

Addison disease |

||

disorder of thegastrointestinal tract in infants. The pylorus |

|||

|

|

||

(>2/week) at low intensity (1-2 emesis/hr). While chronic |

is thickened and elongated with narrowing of its lumen |

||

due to hypertrophy of the circularmusclefibersof pylorus. |

|||

vomiting is usually caused by a gastrointestinal etiology, |

Clinical presentation. The classical presentation is with non |

||

cyclic vomiting is predominantly due to neurologic, |

|||

bilious vomiting that gradually increases infrequency and |

|||

metabolic and endocrine causes. |

|||

severity to become projectile in nature. The disorder is |

|||

|

|

||

Evaluation |

|

4-6 times more common in boys than girls. Most patients |

|

A detailed history and examination often gives clue to the |

present with vomiting starting beyond 3 weeks of age; |

||

however, about 20% are symptomatic since birth and |

|||

diagnosis. The etiology of vomiting varies according to |

|||

presentation is delayed until 5 months of age in others. |

|||

age; while infectious causes occur across all ages, most |

|||

Constipation is common.Recurrent and persistent vomi |

|||

congenitalanomalies,e.g. atresiaor stenosis andmetabolic |

|||

ting causes dehydration, malnutrition and hypochloremic |

|||

disorders, present in the neonatal period or infancy. The |

|||

alkalosis. As the stomach muscles contract forcibly to |

|||

first step is to find out whether the vomitus is bilious or |

|||

overcome the obstruction, a vigorous peristaltic wave can |

|||

nonbilious. This determines the site of disease. Lesions |

|||

be seen to move from left hypochondrium to umbilicus, |

|||

beyond the ampulla of Vater cause bilious vomiting and |

|||

particularly on examination after feeding. A firm olive |

|||

those proximal to it lead to nonbilious vomiting. Asso |

|||

shaped mass is palpable in the midepigastrium in 75-80% |

|||

ciated features may indicate etiology, e.g. vomitus con |

|||

infants, especially after feeds. |

|||

taining stale food of previous day (suggests gastric outlet |

|||

|

|||

obstruction), visible peristalsis (obstruction), vomiting in |

Evaluation. Ultrasound abdomen is the diagnostic |

||

early morning (intracranial neoplasm or cyclic vomiting |

investigation and shows muscle thickness of >4 mm and |

||

syndrome), vertigo (middle ear disorder) and hypotonia |

pyloruslengthof>16mm. Theultrasoundis100%sensitive |

||

(mitochondrial disorders). The 'red flag' symptoms and |

and nearly 90% specific in diagnosis of hypertrophic |

||

signs in a child with vomiting are the presence of blood |

pyloric stenosis. However, in case of doubt, an upper GI |

||

or bile in the vomitus, severe abdominal pain with |

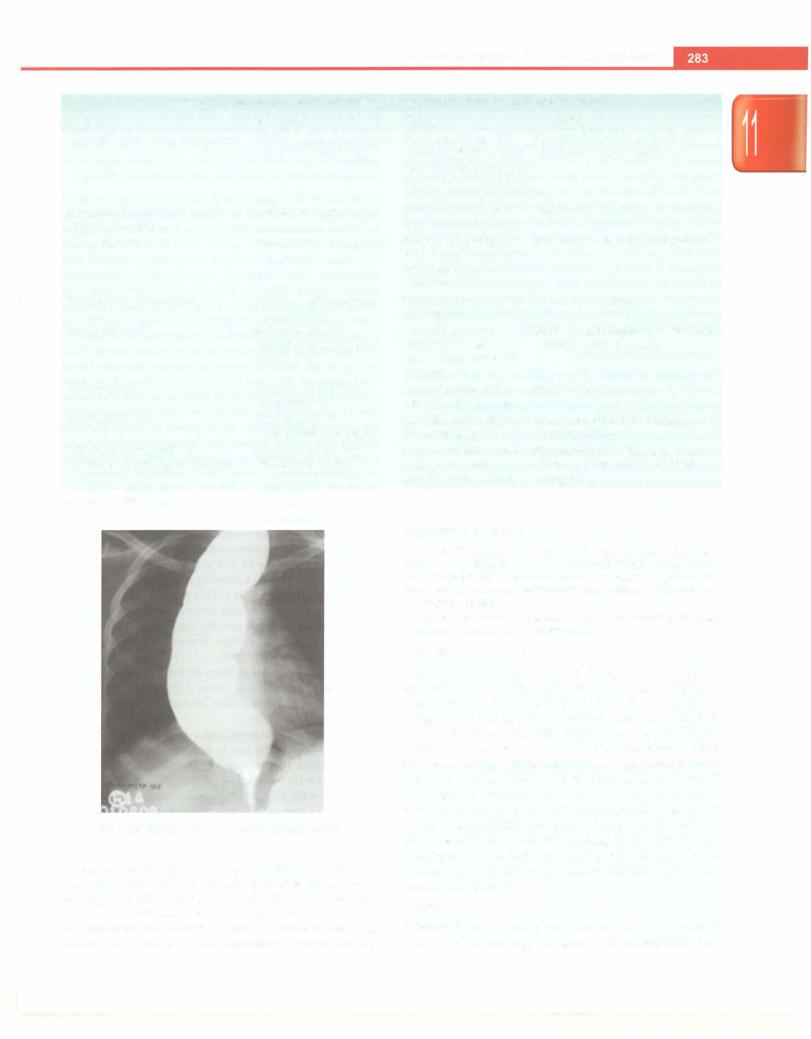

barium study can show a consistent elongation of the |

||

abdominal distension or tenderness, projectile vomiting, |

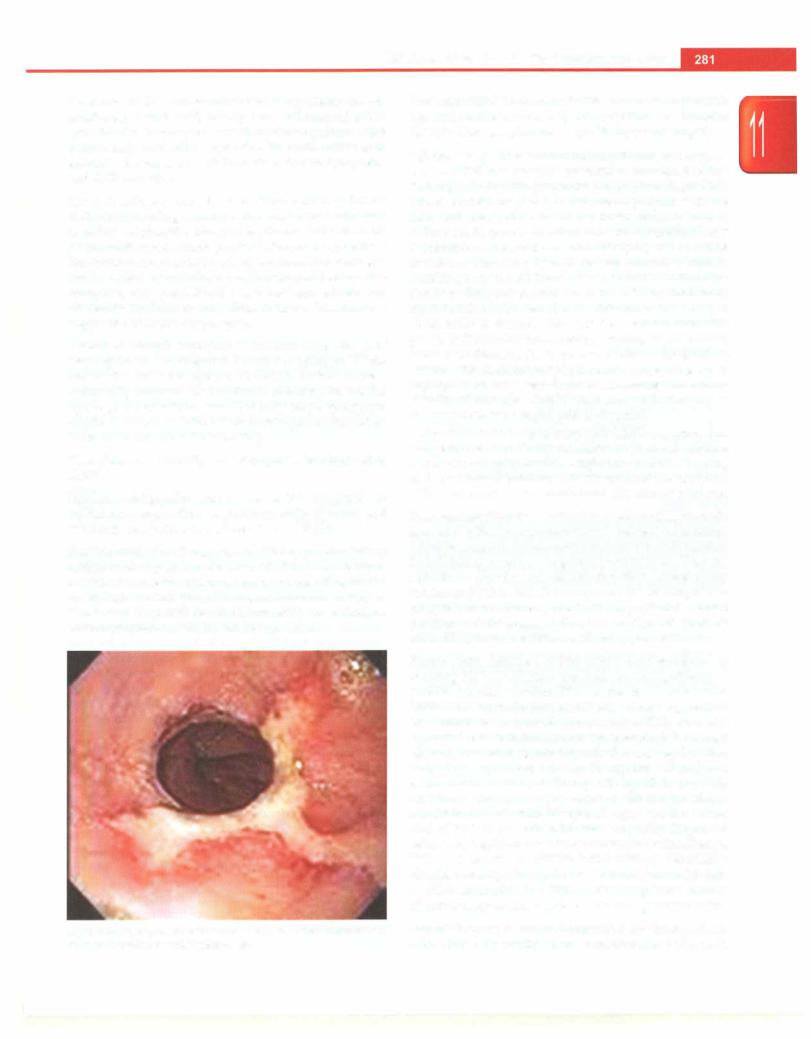

pyloric channel (Fig. 11.1) or an upper GI endoscopy is |

||

persistent tachycardia or hypotension, neckstiffness and/ |

performed. |

||