Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

--------------------------------------.N;,u_tr.i;, ,;;tio.;.n;.;_-

Factors to be Considered while Planning Food for the Child

There are six cardinal factors to be considered while feeding the child:

1. Energy density. Most of our traditional foods are bulky and a child cannot eat large quantities at a time. Hence, it is important to give small energy dense feeds at frequent intervals to ensure adequate energy intakes by the child. Energy density of foods given to infants and young children can be increased without increasing the bulk by adding a teaspoon of oil or ghee in every feed. Fat is a concentrated source of energy and increases energy content of food without increasing the bulk. Sugar and jaggery can be added in infant foods. Amylase rich foods such as malted foods reduce the viscosity of the foods and therefore, the child can eat more quantities at a time (malting is germinating whole grain cereal or pulse, drying and then grinding). Thin gruels do not provide enough energy; a young infant particularly during 6-9 months requires thick but smooth mixtures.

2. Amount of feed. At 6 months of age, feed should be started with small amount as much as 1-2 teaspoons and the quantity is increased gradually as the child gets older and starts to accept food better. Child should be given time to adapt gradually to larger quantities from teaspoon to tablespoon and then to a katori.

3. Consistency of feed. Infants can eat pureed, mashed and semisolid foods beginning at six months. By 8 months, most infants can also eat finger foods (snacks that can be eaten by children alone). By 12 months, most children can eat the same types of foods as consumed by the rest of the family. As the child grows older, he should be shifted to more appropriate foods suitable for his age. Foods that can cause choking such as nuts, grapes, raw carrots should be avoided. For small children, the food should not contain particulate matter that may trigger gag reflex or vomiting.

4. Frequency of feeding. An average healthy breastfed infant needs complementary foods 2-3 times per day at 6-8 months of age and 3-4 times per day at 9-24 months. For children 12-24 months of age, additional nutritious snacks such as a piece of fruit should also be offered 1-2 times per day. Snacks are defined as foods eaten between meals that are convenient and easy to prepare. If energy density or amount of food per meal is low, or the child is no longer breastfed, more frequent meals should be provided.

5. Hygiene. Goodhygieneandproperfoodhandling should be practiced to prevent children from infections and malnutrition.Simplepractices include: (i) washinghands before food preparation and eating, (ii) serving freshly cooked foods (cooked food should not be kept for more than 2-3 hr), (iii) using cleanutensils, (iv) coveringfood properly, and (v) avoiding use of feeding bottles.

6. Helping the child. Feeding the infants and children should be an active, engaging and interactive affair.

Often the food is left in front of the child to eat. This approach is not appropriate. Parents should actively engage with the child in feeding, making the child sit in the lap and feeding him affectionately in small portions with spoon or with small morsels. The older child is coaxed and encouraged to finish the desired amount of food.

UNDERNUTRITION

Undernutrition is a condition in which there is inadequate consumption, poor absorption or excessive loss of nutrients. Overnutrition is caused by overindulgence or excessive intake of specificnutrients. The term malnutrition refers to both undernutrition as well as overnutrition. However, sometimes the terms malnutrition and protein energy malnutrition (PEM) are used interchangeably with undernutrition.

Malnourished children may suffer from numerous associated complications. They are more susceptible to infections, especially sepsis, pneumonia and gastro enteritis. Vitamin deficiencies and deficiencies of minerals and trace elements can also be seen. Malnutrition in young children is conventionally determined through measurement of height, weight, skinfold thickness (or subcutaneous fat) and age. The commonly used indices derived from these measurements are given in Table 6.6.

Epidemiology

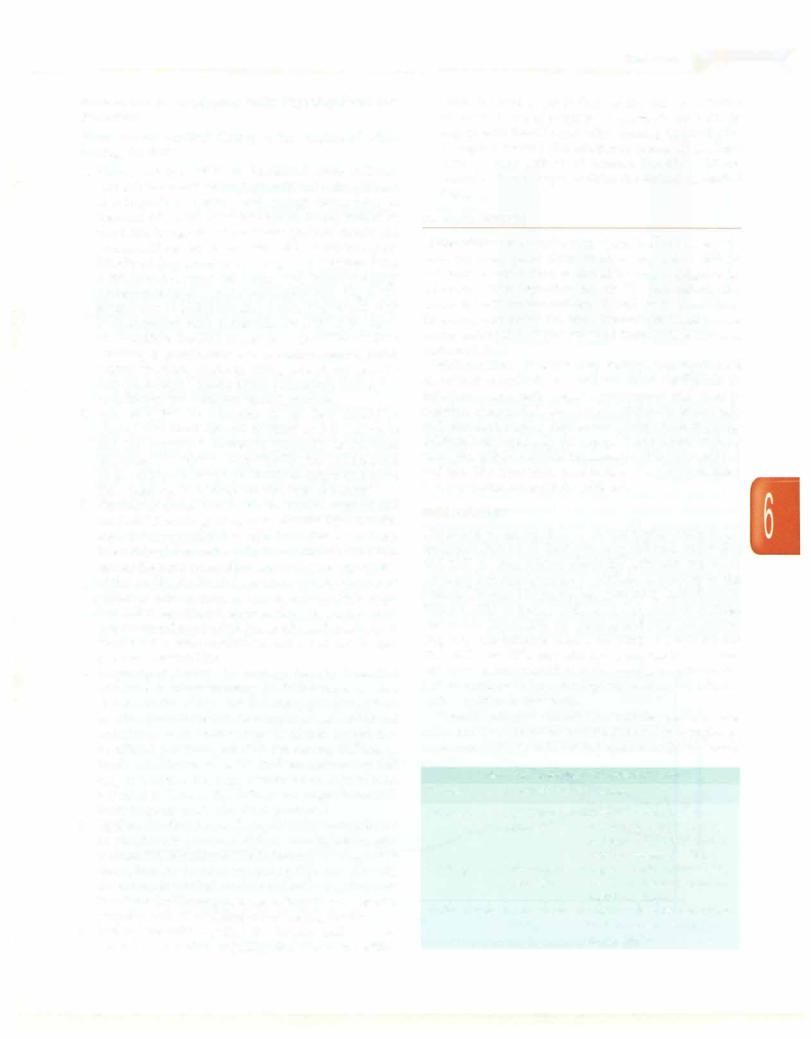

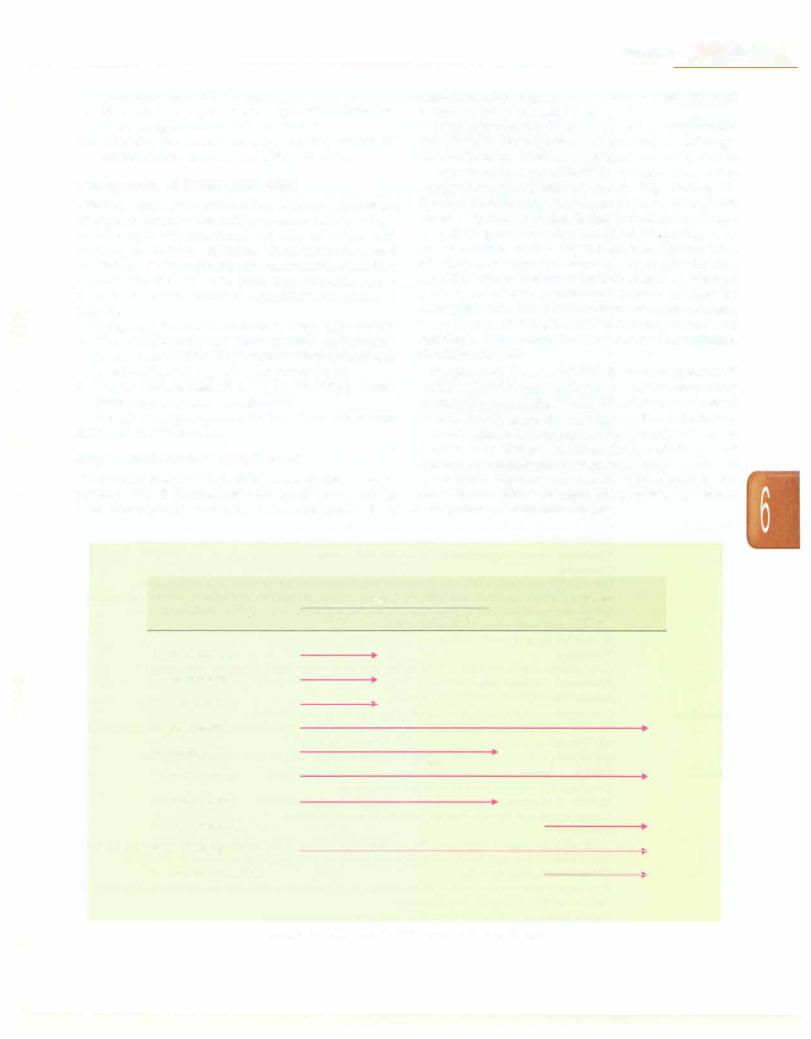

Childhood undernutrition is an underlying cause in an estimated 35% of all deaths among children under five and 21% of total global disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost among under 5 children. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 3, carried out in 2005-06, 40% of India's children under the age of three are underweight, 45% are stunted and 23% are wasted (Fig. 6.2). Comparable figures for NFHS 2 (1998-99) are 43%, 51% and 20%, respectively. There has been a slow reduction in undernutrition in the country over the years, but we continue to have the highest burden of childhood undernutrition in the world.

Overall, both girls and boys have similar prevalence of undernutrition. Prevalence of undernutrition is higher in rural areas (46%) than in urban populations (33%). Levels

Table 6.6: Indicators of undernutrition

Indicator |

Interpretation |

Comment |

Stunting |

Low height |

Indicator of chronic |

|

for-age |

malnutrition, the result of |

|

|

prolonged food deprivation |

|

|

and/or disease or illness |

Wasting |

Low weight |

Suggests acute malnutrition, |

|

for-height |

the result of more recent food |

|

|

deficit or illness |

Underweight |

Low weight |

Combined indicator to reflect |

|

for-age |

both acute and chronic |

|

|

malnutrition |

- Essential Pediatrics

6

51

|

|

|

•NFHS 2 |

|

|

|

(1998-1999) |

0 |

|

|

NFHS 3 |

(l) |

|

|

(2005-2006) |

Ol |

|

|

|

.'9 |

2 |

|

|

C |

|

|

|

(l) |

|

|

|

(l) |

|

|

|

a.. |

|

|

|

|

0 |

Wasted |

Underweight |

|

Stunted |

Fig. 6.2: Trends in nutritional status of children under 3 yr in India,

Source, National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2 and 3

of malnutrition vary widely across Indian states. Punjab, Kerala, Jammu and Kashmir and Tamil Nadu account for the lowest proportions (27-33%) of underweight children; while Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh report the maximum (52-60%) levels of under weight children.

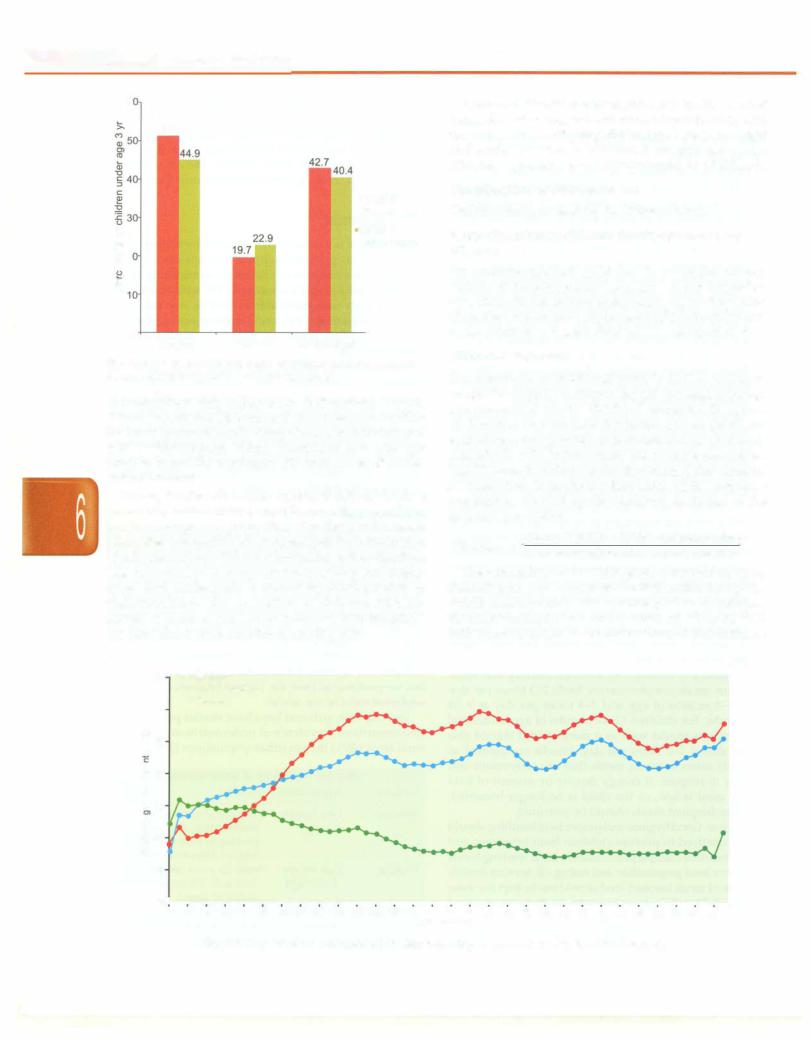

During the first six months of life, 20-30% of children are already malnourished, often because they were born low birthweight. The proportion of undemutrition starts rising after 4-6 months of age because of the introduction of unhygienic foods that cause infections suchas diarrhea. Late introduction of complementary feeding and inade quate food intake leads to increasing predisposition to undernutrition. The proportion of children who are stunted or underweight increases rapidly withthe child's age until about 18-24 months of age (Fig. 6.3).

Undemutrition isstronglyassociated withshorteradult height, lessschooling,reduced economic productivity and, for women, lower offspring birthweight. Low birthweight and undernutrition in childhood are risk factors for diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemias in adulthood.

Classification of Undernutrition

Undemutrition is classified in different ways.

Basic Groupings: Undernourished, Stunted and Wasted

An undernourished child has low weight-for-age (Table 6.6). Stunting means being short or low height-for age. This indicateschronic undernutrition.Wastingon the other hand means low weight-for-height indicating acute undernutrition. Awasted child has an emaciated look.

WHO Classification

The assessment of nutritional status is done according to weight-for-height (or length), height (or length)-for-age and presence of edema. The WHO recommends the use of Z scores or standard deviation scores (SOS) for evaluatinganthropometric data,soastoaccurately classify individuals with indices below the extreme percentiles. The SD score is defined as the deviation of the value for an individual from the median value of the reference population, divided by the standard deviation of the reference population.

Observed value - Median reference value SD score = Standard deviation of reference population

The calculation of the SOS gives a numerical score indicating how far away from the 50th centile for age the child's measurements falls. A score of -2 to -3 indicates moderate malnutrition and a score of +2 to +3 SOS indicates overweight. Ascore of less than -3SOSindicates

70..... stunted

..... Underweight

..... Wasted

60

l so

U)

.c

0

E 40

30

"'

C:

20 i:

u

10

o-l---,--..-----,------,--- |

.....18 |

---,--..-----,--..-- |

.....30 |

---,--..---,---,--..-- |

.....42 |

---,--..---,---,--..---.---,--,- |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

o |

2 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

14 |

16 |

20 |

22 |

24 |

26 |

28 |

32 |

34 |

36 |

38 |

40 |

44 |

46 |

48 |

50 |

52 |

54 |

56 |

58 |

|||

Age (months)

Fig. 6.3: Proportions of malnourished children according to age (National Family Health Survey 3)

--------------------------------------N_u_t_ri-ti_o_n__

severe malnutrition and a score of more than +3 indicates obesity. WHO growth charts are provided in Chapter 2.

The term 'edematous malnutrition' is used if edema is also present. Clinical classification of undernutrition as marasmus, kwashiorkor and marasmic kwashiorkor is helpful (discussed below).

/AP Classification

This classification proposed by the Indian Academy of Pediatricsisbasedonweightforagevalues(Table6.7).The standardusedinthisclassification forreferencepopulation was the 50th centile of the old Harvard standards.

Table 6.7: IAP classification of malnutrition

Grade of malnutrition |

Weight-for-age ofthe standard (%) |

|

Normal |

>80 |

|

Grade I |

71-80 |

(mild malnutrition) |

Grade II |

61-70 |

(moderate malnutrition) |

Grade ill |

51-60 |

(severe malnutrition) |

Grade IV |

<50 (very severe malnutrition) |

|

Marasmus, Kwashiorkor, Marasmic Kwashiorkor

Based on the appearance, undernourished child may have marasmus or kwashiorkor or marasmic kwashiorkor. These severe forms of malnutrition are described later in this chapter.

Age Independent Indices to Diagnose Undernutrition

In many situations the child's age is not known, e.g. children from orphanages, street children, during natural disasters, etc. This has prompted many attempts to devise methods of interpreting anthropometric data, which do not require knowledge of precise age. Various variables change slowly over certain broad age ranges and thus are regarded as independent of age over these ranges (Table 6.8). Certain tools have been developed to simplify the measurement for field workers and give a visible indicator of the degree of malnutrition.

Mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) It is a widely used measurement and requires minimum equipment. It increases rapidly in thefirstyear (11-16cm)andthenbeen found to be relatively stable between the ages 1 and 5 yr at a value of between 16 and 17 cm. Any value below 13.5 cm is abnormal and suggestive of malnutrition. A

value below 11.5 cm is suggestive of severe malnutrition. Recently, it has been shown that MUAC may not be age independent and therefore, the WHO recommends MUAC-for-age reference data to be used in girls andboys 6-59 month old where possible.

Shakir tape method This special tapehas colored zones: red, yellow and greencorrespondingto <12.5 cm (wasted), 12.5 to 13.5 cm (borderline) and over 13.5 cm (normal) MUAC respectively.

Bangle test A bangle with internal diameter of 4 cm is passed above the elbow. In severe malnutrition it can be passed above the elbow, in normal children it cannot.

Skinfold thickness It is an indication of the subcutaneous fat. Triceps skin fold is the most representative of the total subcutaneous fat up to sixteen years of age. It is usually above 10 mm in normal children whereas in severely malnourished it may fall below 6 mm.

Severe Acute Malnutrition

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) among children 6-59 months of age is defined by World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF as any of the following: (i) weight for-height below -3 standard deviation (SD or Z scores) of the median WHO growth reference; (ii) visible severe wasting; (iii) presence of bipedal edema; or (iv) mid upper arm circumference below 11.5 cm. This classification is used to identify children at high-risk of death. Children having SAM require urgent attention and management in the hospital. In a child below 6 months of age, the MUAC can not be used, and SAMshouldbe diagnosed in thepresence of (i), (ii) or (iii).

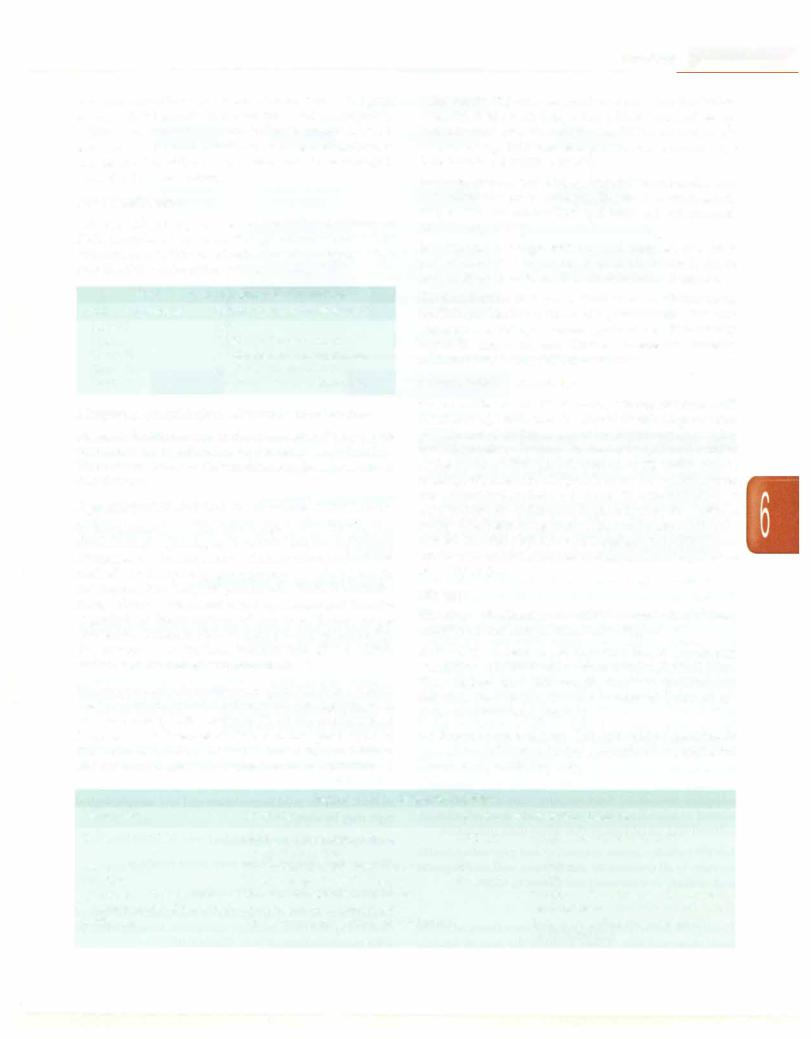

Etiology

The causes of malnutrition couldbe viewed as immediate, underlying and basic as depicted in Fig. 6.4. Immediate determinants The immediate determinants of a child's nutritionalstatus work at the individual level. They include low birthweight, illnesses (particularly infections such as diarrhea and pneumonia) and inade quate dietary intake (Box 6.2).

Underlying determinants The immediate determinants are in turn influenced by three household determinants namely food, health and care.

|

Table 6.8: Age independent indices |

|

|

Name ofindex |

Calculation |

Normal value |

Value in malnutrition |

Kanawati and McLaren |

Mid-arm circumference/head |

0.32-0.33 |

Severely malnourished <0.25 |

|

circumference (cm) |

|

|

Rao and Singh |

Weight (in kg) x 100/height2 (in cm) |

0.14 |

0.12-0.14 |

Dugdale |

Weight (in kg)/height16 (in cm) |

0.88-0.97 |

< 0.79 |

Quaker arm circumference |

Mid-arm circumference that would |

|

75-85% malnourished; <75% severely |

measuring stick (Quac stick) |

be expected for a given height |

|

malnourished |

Jelilfe ratio |

Head circumference/chest circumference |

|

Ratio <1 in a child >1 yr suggests |

|

|

|

malnutrition |

__E_s_s_e_n_ tii_aP_e_d_i a _tr-ics_________________________________

Nutritional status

|

|

|

|

|

|

Immediate |

|

|

|

|

|

determinants |

|

|

|

|

|

and services |

|

Underlying |

|

|

|

|

|

determinants |

|

Resources for food secur |

Resources for care |

Resources for health |

|

|

||

|

Food production |

|

Caregiver control of |

Safe water supply |

|

|

|

Cash income |

resources and autonomy |

Adequate sanitation |

|

|

|

Transfers of food in-kind |

Caregiver physical and |

Health care availability |

|

|

||

|

|

|

initial status |

Environmental safety |

|

|

|

|

|

Caregiver knowledge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

and beliefs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[POVERTY! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Political and economic structure |

I |

|

Basic |

|

|

|

Sociocultural environment |

|

determinants |

|

Fig. 6.4: Determinants of a child's nutrition status

Box 6.2: Three immediate causes of undernutrition

•Low dietary intake: Delayed complementary feeding and inadequate intake of food means less nutrients available for growth

•Low birthweight: Infants born small, often remain small

•Infection: Diarrhea, pneumonia and other infections consume energy and hamper growth. Diarrhea causes nutrition loss in stool

Food refers to food security at the household level. It is the sustainable access to safe food of sufficient quality and quantity, paying attention to energy, protein and micronutrients. This in-turn depends on having financial, physicalandsocialaccessas distinctfrom mere availability.

Care refers to a process taking place between a caregiver and the receiver of care. It translates food availability at the household level and presence of health services into growth and development of the child. Households may have an abundance of food but still have malnourished children attributed to absence of care. Care includes care for women, breastfeeding and complementary feeding, home health practices, hygiene practices, psychosocial care and food preparation. The factors that determine adequate household food security, care and health are related to resources, their control and a host of political, cultural and social factors that affect their utilization.

Health includes access to curative and preventive health services to all community members as well as a hygienic and sanitary environment and access to water.

status and education level of the families, women's empowerment, cultural taboos regarding food andhealth, access to water and sanitation, etc.

Pathological Features

Malnutrition affects almost all organ systems. The salient findings in various organs or tissues are elucidated in Table 6.9.

Clin ical Features of Malnu rit on i

Mild Malnutrition

Itis most common between the ages of 9 months and 2 yr. Main features are as follows:

Growthfailure. This is manifested by slowing or cessation of linear growth; static or decline in weight; decrease in mid-arm circumference; delayedbonematuration; normal or diminished weight for height Z scores; and normal or diminished skin fold thickness.

Infection. A high rate of infection involving various organ systems may be seen, e.g. gastroenteritis, pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Anemia. May be mild to moderate and any morphological type may be seen.

Activity. This may be diminished

Skin and hair changes. These may occur rarely.

Moderate to Severe Malnutrition

Basic Determinants

Finally, the underlyingdeterminants are influencedby the basic determinants. These include the socioeconomic

Moderate to severe malnutrition is associated with one of classical syndromes, namely, marasmus, kwashiorkor, or with manifestations of both (Table 6.10).

--------------------------------------- |

N_u_t_ri-ti_o_n |

|

Table 6.9: Pathological changes in malnutrition in various organ systems |

Upper gastrointestinal |

Mucosa shiny and atrophic, papillae of tongue flattened |

tract |

|

Small and large intestine |

Mucosa and villi atrophic; brush border enzymes reduced; hypotonic, rectal prolapse |

Liver |

Fatty liver, deposition of triglycerides |

Pancreas |

Exocrine secretion depressed; endocrine function less severely affected; glucagon production |

|

reduced; insulin levels low; atrophy and degranulation or hypertrophy of islets seen |

Endocrine system |

Elevated growth hormone; thyroid involution and fibrosis; adrenal glands atrophic and cortex |

|

thinned; increased cortisol; catecholamine activity unaltered |

Lymphoreticular |

Thymus involuted; loss of distinction between cortex and medulla; depletion of lymphocytes; |

system |

paracortical areas of lymph nodes depleted of lymphocytes; germinal centers smaller and fewer |

Central nervous system |

Head circumference and brain growth retarded; changes seen in the dendritic arborization and |

|

morphology of dendritic spines; cerebral atrophy on CT/MRI; abnormalities in auditory brainstem |

|

potentials and visual evoked potentials |

Cardiovascular system |

Changes in cardiac volume, muscle mass and electrical properties of the myocardium; systolic |

|

function affected more than diastolic function |

Table 6.10: Differences between kwashiorkor and marasmus

Clinical finding |

Marasmus |

Kwashiorkor |

Occurrence |

More common |

Less common |

Edema |

Absent |

Present |

Activity |

Active |

Apathetic |

Appetite |

Good |

Poor |

Liver |

Absent |

Present |

enlargement |

|

|

Mortality |

Less than kwashiorkor |

High in early stage |

Recovery |

Recover early |

Slow recovery |

Infections |

Less prone |

More prone |

Marasmus

It results from rapid deterioration in nutritional status. Acute starvation or acute illness over a borderline nutritional status could precipitate this form of under nutrition. It is characterized by marked wasting of fat and muscle as these tissues are consumed to make energy.

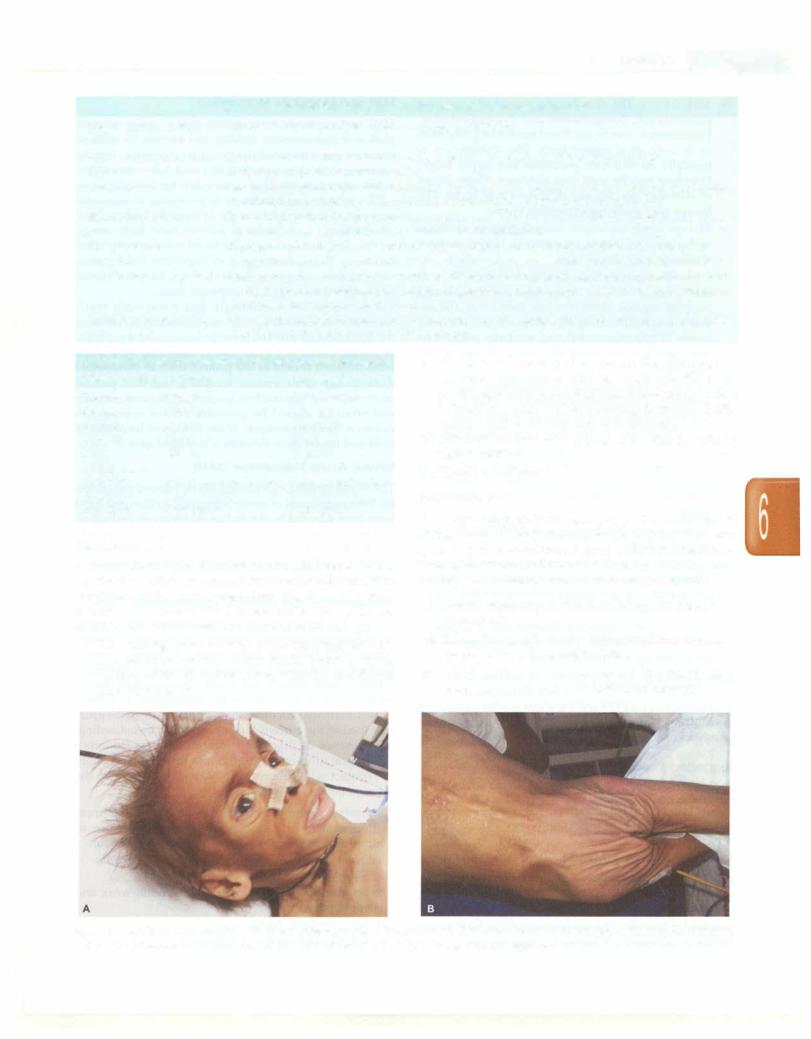

i.The main sign is severe wasting. The child appears very thin (skin and bones) and has no fat. There is severe wasting of the shoulders, arms, buttocks and thighs (Figs 6.SA and B).

ii.The loss of buccal pad of fat creates the aged or wrinkled appearance that has been referred to as

monkey facies (Fig. 6.SA). Baggy pants appearance refers to loose skin of the buttocks hanging down (Fig. 6.SB). Axillary pad of fat may also be diminished

iii.Affected children may appear to be alert in spite of their condition

iv.There is no edema

Kwashiorkor

It usually affects children aged 1--4 yr. The main sign is pitting edema, usually starting in the legs and feet and spreading, in more advancedcases, to the hands and face. Because of edema, children with kwashiorkor may look healthy so that their parents view them as well fed.

i. General appearance. Child may have a fat sugar baby

appearance.

ii. Edema. It rangesfrom mildtogross and may represent up to 5-20% of the body weight.

iii. Muscle wasting. It is always present. The child is often weak, hypotonic and unable to stand or walk.

Figs 6.SA and B: An 8-yr-old child with severe acute malnutrition. Note the (A) dull, lustreless, sparse hair; temporal hollowing; loss of buccal pad of fat; anxious look; CB) loose folds of skin in the gluteal region giving a 'baggy pant' appearance

___Essen_tiiaP__edi_a tr-cis_________________________________

iv.Skin changes. The skin lesions consist of increased pigmentation, desquamation and dyspigmentation. Pigmentation maybe confluent resemblingflaky paint or in individual enamel spots. The distribution is typically on buttocks, perineum and upper thigh. Petechiae may be seen over abdomen. Outer layers of skin may peel off and ulceration may occur. The lesions may sometimes resemble burns.

v.Mucous membrane lesions. Smooth tongue, cheilosis and angularstomatitis are common. Herpes simplex stomatitis may also be seen.

vi.Hair. Changes include dyspigmentation, loss of characteristic curls and sparseness over temple and occipital regions. Hairs also lose their lustre and are easily pluckable. A flag sign which is the alternate bands of hypopigmented and normally pigmented hair pattern is seen when the growth of child occurs in spurts.

vii.Mental changes. Includes unhappiness, apathy or irritability with sad, intermittent cry. They show no signs of hunger and it is difficult to feed them.

viii.Neurological changes. These are seen during recovery.

ix.Gastrointestinal system. Anorexia, sometimes with vomiting, is the rule. Abdominal distension is characteristic. Stools may be watery or semisolid, bulky with a low pH and may contain unabsorbed sugars.

x.Anemia. It may also be seen, as in mild PEM, but with greater severity.

xi.Cardiovascular system. The findings include cold, pale extremities due to circulatory insufficiency and are associated with prolonged circulation time, brady cardia, diminished cardiac output and hypotension.

xii.RenalJunction. Glomerularfiltrationand renalplasma flow are diminished. There is aminoaciduria and inefficient excretion of acid load.

Marasmic Kwashiorkor

Itis amixed formofPEMandmanifestsasedemaoccurring in children who may or may not have other signs of kwashiorkorand havevaried manifestations ofmarasmus.

Suggested Reading

Victora C, Adair L, Fall C, et al. Maternal and child undemutrition: consequences for adulthealth and human capital. Lancet 2008; 371;340--57 World Health Organization. The management of nutrition in major

emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000

MANAGEMENT OF MALNUTRITION

The management of malnutrition depends on its severity. While mild to moderate malnutrition can be managed on ambulatory basis, severe malnutrition is preferably managed in hospital. Themanagement oflowbirthweight infants is discussed in Chapter 8.

Mild and Moderate Malnutrition

Mild and moderate malnutrition make up the greatest portion of malnourished children andaccount for >80% of malnutrition associated deaths. It is, therefore, vital to interveneinchildrenwithmildandmoderate malnutrition at the community levelbeforethey develop complications.

The mainstay of treatment is provision of adequate amounts of protein and energy; at least 150 kcal/kg/day should be given. In order to achieve these high energy intakes,frequent feeding (up toseventimesa day)is often necessary. Because energy is so important and because carbohydrate energy sources are bulky, oil isusually used to increase the energy in therapeutic diets.

It is recognized increasingly that a relatively small increase over normal protein requirements is sufficient for rapid catchup growth, provided energy intake is high. A protein intake of 3 g/kg/day is sufficient. Milk is the most frequent source of the protein used in therapeutic diets, though other sources, including vegetable protein mixtures,have been usedsuccessfully. Adequateminerals and vitamins should be provided for the appropriate duration. Thebest measure of the efficacy of treatment of mild and moderate malnutrition is weight gain.

Severe Acute Malnutrit on (SAM) i

The World Health Organization hasdevelopedguidelines for themanagement ofsevereacutemalnutritionand these have been adapted by the Indian Academy of Pediatrics. At the community level, the four criteria listed previously should be used to diagnose severe acute malnutrition.

WHOrecommendsexclusiveinpatientmanagementofchildren with severe acute malnutrition.

Assessment of the Severely Malnourished Child

History. The child with severe malnutrition has a complex backdrop with dietary, infective, social and economic factors underlying the malnutrition. A history of events leading to the child's admission should be obtained. Socioeconomic history and family circumstances should be explored to understand the underlying and basic causes. Particular attention shouldbe givento: (i)theusual diet (before the current illness) including breastfeeding;

(ii)presence of diarrhea (duration, watery/bloody);

(iii)information on vomiting, loss of appetite, cough;

(iv)contact with tuberculosis. Malnutrition may be the presentation of HIV infection.

Examination.Anthropometry providesthemainassessment of the severity of malnutrition. Physical features of malnutrition as described above should be looked for.

Clinical features of prognostic significance include:

i.Signs of dehydration

ii.Shock (cold hands, slow capillary refill, weak and rapid pulse)

iii.Severe palmar pallor

iv.Eye signs of vitamin A deficiency

---------------------------------------N_u_t_rti-oin__

v.Localizing signs of infections

vi.Skin infection or pneumonia, signs of HIV infection, fever (temperature 37.5°C or 99.5°F)

vii.Hypothermia (rectaltemperature <35.5°C or <95.9°F), mouth ulcers, skin changes of kwashiorkor.

Managementof Severe Malnutrtioni

Children with severe malnutrition undergo physiologic changes to preserve essential processes, which include reductions in the functional capacity of organs and slowing of cellular activities. These alterations and coexisting infections put severely malnourished children at particular risk of death from hypoglycemia, hypo thermia, electrolyteimbalance, heart failure and untreated infection.

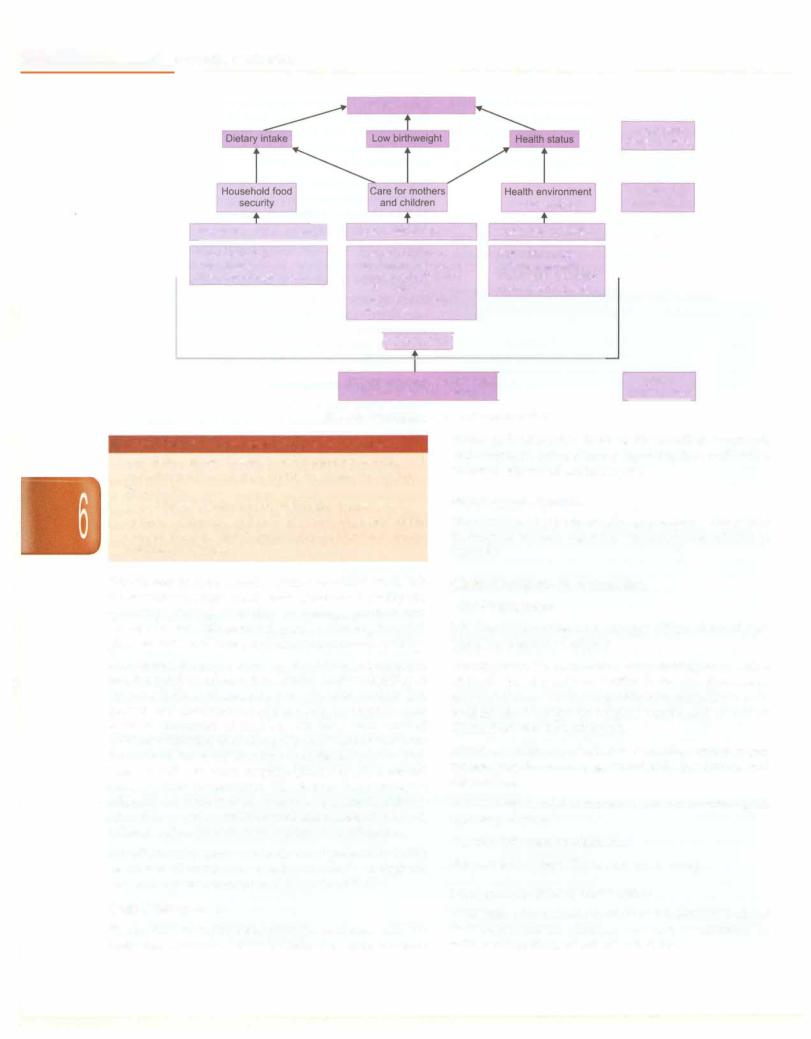

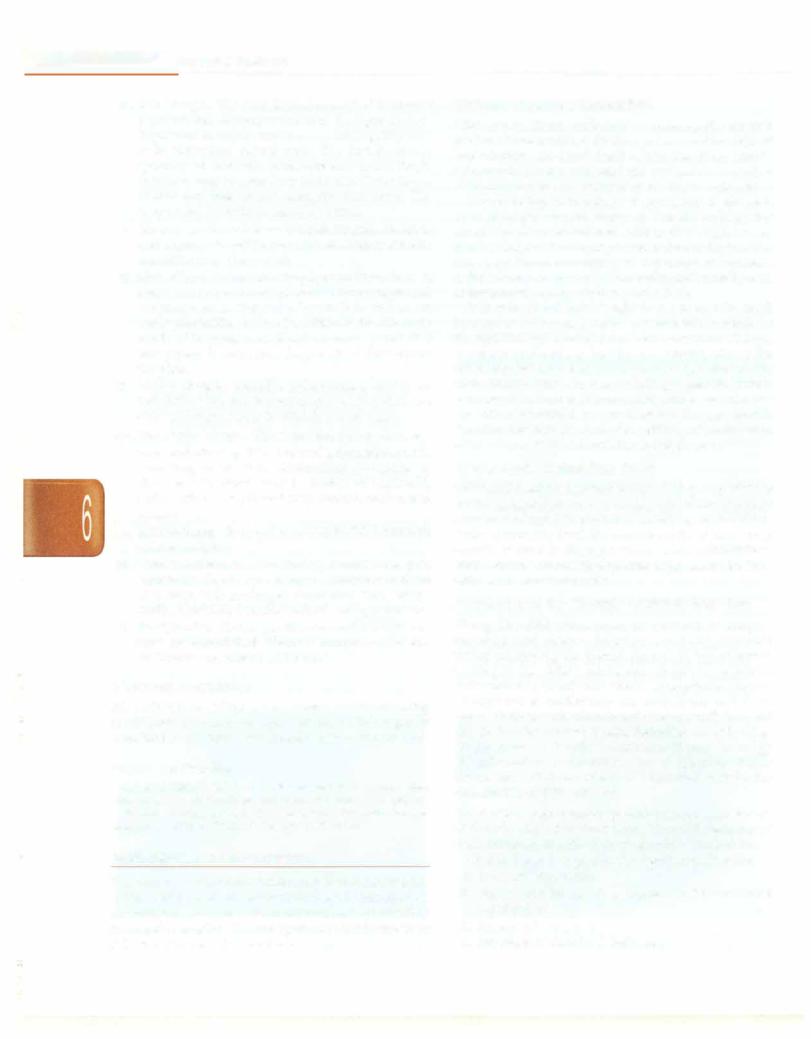

The general treatment involves ten steps in two phases:

•The initial stabilization phase focuses on restoring homeostasis and treating medical complications and usually takes 2-7 days of inpatient treatment.

•The rehabilitation phase focuses on rebuilding wasted tissues and may take several weeks.

The ten essential steps and the time frame are shown in Fig. 6.6 and Table 6.11.

Step 1: Treat/Prevent Hypoglycemia

All severely malnourished children are at risk of hypo glycemia (blood glucose level <54 mg/dl or 3 mmol/1), hence blood glucose should be measured immediately at

admission.If bloodglucosecannotbe measured, onemust assume hypoglycemia and treat.

Hypoglycemia may be asymptomatic or symptomatic.

Symptomatic hypoglycemia manifesting as lethargy, unconsciousness, seizures, peripheral circulatory failure or hypothermia is more common in marasmus, where energy stores are depleted or when feeding is infrequent. For correction ofasymptomatichypoglycemia, 50 ml of 10% glucose or sucrose solution (1 rounded teaspoon of sugar in 31h tablespoons of water) should be given orally or by nasogastric tube followed by the first feed. For correction of symptomatic hypoglycemia, 5 ml/kg of 10% dextrose should be given intravenously. This should be followed with 50 ml of 10% dextrose or sucrose solution by nasogastric tube. Blood glucose levels must be estimated every 30 min till the glucose level becomes normal and stabilizes. Once stable, the 2 hourly feeding regimens should be started.

Feeding should be started with starter F-75 (Formula 75 whichis aWHO recommendedstarterdietforsevereacute malnutrition containing 75 kcal/100 ml of feed (described later) as quickly as possible and then continued 2-3 hourly day andnight(initiallya quarter ofthe2hourlyfeedshould be given every30 mintilltheblood glucosestabilizes).Most episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia can be prevented by frequent, regular feeds and the child should be fed regularly throughout the night. Hypoglycemia, hypothermia and infection generally occur as a triad.

Steps |

Stabilization |

Rehabilitation |

|

|

|

|

Weeks 2-6 |

|

Days 1-2 |

Days 3-7 |

|

1.Hypoglycemia

2.Hypothermia

3.Dehydration

4.Electrolytes

5.Infection

|

|

No iron |

With iron |

6. |

Micronutrients |

|

|

7. |

Initiate feeding |

|

|

8. |

Catchup growth |

|

|

9. |

Sensory stimulation |

|

|

|

|

||

10. |

Prepare for followup |

|

|

|

|||

Fig. 6.6: The time frame for initiating and achieving 10 steps

|

E |

|

|

|

s |

_____________ |

________ |

|

|

s s e n |

tia P e d i atric |

_ |

|||

|

__ |

_ |

_ |

_ _ |

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ - _ ___________ |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.11: Summary of the management of severe malnutrition |

|

|

|

Hypoglycemia |

|

Blood glucose level <54 mg/dl or 3 mmol/1 |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

If blood glucose cannot be measured, assume hypoglycemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypoglycemia, hypothermia and infection generally occur as a triad |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Asymptomatic hypoglycemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Give 50 ml of 10% glucose or sucrose solution orally or by nasogastric tube followed by first feed |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Feed with starter F-75 every 2 hourly day and night |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symptomatic hypoglycemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Give 10% dextrose IV 5 ml/kg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow with 50 ml of 10% dextrose or sucrose solution by nasogastric tube |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feed with starter F-75 every 2 hourly day and night |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Start appropriate antibiotics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prevention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feed 2 hourly starting immediately |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prevent hypothermia |

|

|

|

Hypothermia |

|

|

Rectal temperature less than <35.5°C or 95.5°F or axillary temperature less than 35°C or 95°F |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Always measure blood glucose and screen for infections in the presence of hypothermia |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clothe the child with warm clothes; ensure that the head is also covered with a scarf or cap |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Provide heat using overhead warmer, skin contact or heat convector |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Avoid rapid rewarming as this may lead to disequilibrium |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feed the child immediately |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Give appropriate antibiotics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prevention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Place the child's bed in a draught free area |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Always keep the child well covered; ensure that head is also covered well |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

May place the child in contact with the mother's bare chest or abdomen (skin-to-skin) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Feed the child 2 hourly starting immediately after admission |

|

|

|

Dehydration |

|

|

Difficult to estimate dehydration status accurately in the severely malnourished child |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Assume that all severely malnourished children with watery diarrhea have some dehydration |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Low blood volume (hypovolemia) can coexist with edema |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Use reduced osmolarity ORS with potassium supplements for rehydration and maintenance |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Amount depends upon how much the child wants, volume of stool loss, and whether the child is vomiting |

||

|

|

|

|

|

Initiate feeding within two to three hours of starting rehydration; use F-75 formula on alternate |

||

|

|

|

|

|

hours along with reduced osmolarity ORS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Be alert for signs of overhydration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prevention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Give reduced osmolarity ORS at 5-10 ml/kg after each watery stool, to replace stool losses |

||

|

|

|

|

|

If breastfed, continue breastfeeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initiate refeeding with starter F-75 formula |

|

|

|

Electrolytes |

|

|

Give supplemental potassium at 3-4 mEq/kg/day for at least 2 weeks |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

On day l, give 50% magnesium sulphate (equivalent to 4 mEq/ml) IM once (0.3 ml/kg; maximum of 2 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

ml). Thereafter, give extra magnesium (0.8-1.2 mEq/kg daily) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excess body sodium exists even though the plasma sodium may be low; decrease salt in diet |

||

|

Iniection |

|

|

Multiple infections are common; assume serious infection and treat |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Usual signs of infection such as fever are often absent |

|

|

Majority of bloodstream infections are due to gram-negative bacteria

Hypoglycemia and hypothermia are markers of severe infection

Treatment

Treat with parenteral ampicillin 50 mg/kg/dose 6 hourly for at least 2 days followed by oral amoxicillin 15 mg/kg 8 hourly for 5 days and gentamicin 7.5 mg/kg or arnikacin 15-20 mg/kg

IM or IV once daily for 7 days

If no improvement occurs within 48 hr, change to IV cefotaxime (100-150 mg/kg/day 6-8 hourly) or ceftriaxone (50-75 mg/kg/day 12 hourly)

If other specific infections are identified, give appropriate antibiotics

Contd.

---------------------------------------N_u_t_ri-ti_o n

|

Table 6.11: Summary of the management of severe malnutrition (Contd.) |

|

Prevention |

|

Follow standard precautions like hand hygiene |

|

Give measles vaccine if the child is >6 mo and not immunized, or if the child is >9 mo and had been |

|

vaccinated before the age of 9 months |

Micronutrients |

Use up to twice the recommended daily allowance of various vitamins and minerals |

|

On day 1, give vitamin A orally (if age >1 yr give 2 lakh IU; age 6-12 mo give 1 lakh IU; age |

|

0-5 mo give 50,000 IU) |

|

Folic acid 1 mg/day (give 5 mg on day 1) |

|

Zinc 2 mg/kg/day |

|

Copper 0.2-0.3 mg/kg/day |

|

Iron 3 mg/kg/day, once child starts gaining weight; after the stabilization phase |

Initiate feeding |

Start feeding as soon as possible as frequent small feeds |

|

If unable to take orally, initiate nasogastric feeds |

|

Total fluid recommended is 130 ml/kg/day; reduce to 100 ml/kg/day if there is severe edema |

|

Continue breastfeeding ad libitum |

|

Start with F-75 starter feeds every 2 hourly |

|

If persistent diarrhea, give a cereal based low lactose F-75 diet as starter diet |

|

If diarrhea continues on low lactose diets give, F-75 lactose free diets (rarely needed) |

Catch-up growth |

Once appetite returns in 2-3 days, encourage higher intakes |

|

Increase volume offered at each feed and decrease the frequency of feeds to 6 feeds per day |

|

Continue breastfeeding ad libitum |

|

Make a gradual transition from F-75 to F-100 diet |

|

Increase calories to 150-200 kcal/kg/day, and proteins to 4--{j g/kg/day |

|

Add complementary foods as soon as possible to prepare the child for home foods at discharge |

Sensory stimulation |

A cheerful, stimulating environment |

|

Age appropriate structured play therapy for at least 15-30 min/day |

|

Age appropriate physical activity as soon as the child is well enough |

|

Tender loving care |

Prepare for followup Primaryfailure to respond is indicated by: Failure to regain appetite by day 4 Failure to start losing edema by day 4 Presence of edema on day 10

Failure to gain at least 5 g/kg/day-by-day 10

Secondaryfailure to respond is indicated by:

Failure to gain at least 5 g/kg/day for consecutive days during the rehabilitation phase

Step 2: Treat/Prevent Hypothermia

All severely malnourished children are at risk of hypothermia due to impairment of thermoregulatory control, lowered metabolic rate and decreased thermal insulation from body fat. Children with marasmus, concurrent infections, denuded skin and infants are at a greater risk. Hypothermia is diagnosed if the rectal temperature is less than 35.5°C or 95.9°F or axillary temperature is less than 35°C or 95°F. A low reading thermometer (range 29-42°C) should be used to measure the temperature of malnourished children. If the temperature does not register on a normal thermometer, hypothermia should be assumed and treated. It can occur in summers as well.

The child should be rewarmed providing heat using radiation (overhead warmer) or conduction (skin contact) or convection (heatconvector).Rapidrewarmingmay lead to disequilibrium and should be avoided.

In case of severe hypothermia (rectal temperature <32°C) warm humidified oxygen should be given fol lowed immediately by 5 ml/kg of 10% dextrose IV or 50 ml of 10% dextrose by nasogastric route (if IV access is difficult). If clinical condition allows the child to take orally, warm feeds should be given immediately or else the feeds should be administered through a nasogastric tube. If there is feed intolerance or another contra indication for nasogastric feeding, maintenance IV fluids (prewarmed) should be started.

In a hypothermic child, hypoglycemia must be looked for and managed. The child's temperature should be monitored every 2 hr till it rises to more than 36.5°C. Temperature monitoring must be ensured especially at night when the ambient temperature falls.

Inmostcases,hypothermiamay bepreventedbyfrequent feeding.Therefore, thechildshouldbefedimmediately and subsequently,every2 hourly. All children shouldbe nursed

- Esse_n tiai_Ped_ ia _tr-ic_s_________________________________

in a warm environment, clothed with warm clothes and covered using a warm blanket. The head should also be covered well with a scarf or a cap. The child could also be putincontactwiththemother'sbarechestorabdomen (skin to-skin) as in kangaroo mother care to provide warmth. Besidesthesemeasures, hypothermia can also be prevented by placing the child's bed in a draught free area away from doors and windows, minimizing exposure after bathing or during clinicalexamination andkeepingthechilddryalways.

Step 3: Treat/Prevent Dehydration

Dehydration tends to be overdiagnosed and its severity overestimated in severely malnourished children. Loss of elasticity of skin may either be due to loss of the subcutaneousfatin marasmus orlossof extracellular fluid in dehydration. In dehydration, the oral mucosa feels dry to the palpating finger gently rolled on the inner side of the cheek. Presence of thirst, hypothermia, weak pulses and oliguria are other signs of dehydration in severely malnourished children. It is important to recognize that low blood volume (hypovolemia) cancoexist with edema. Since estimation of dehydration may be difficult in severely malnourished children, it is safe to assume that all patients with watery diarrhea have some dehydration.

The Indian Academy of Pediatrics has recommended theuse of onesolutionfor alltypes ofdiarrheain allclinical settings and there is evidence to suggest that the new reduced osmolarity ORS with potassium supplements, given additionally, is effective in severe malnutrition.

Dehydration should be corrected slowly over a period of 12 hr. Some dehydration can be corrected with ORS. Intravenous therapy should be given only for severe

dehydration and shock or if the enteral route cannot be used.

ORS is given orally or by nasogastric tube at 5ml/kg every 30 min for first 2 hr and then at 5-10 ml/kg every hour for the next 4-10 hr. The exact amount actually depends on how much the child wants, volume of stool loss and whether child is vomiting. Ongoing stool losses should be replaced with approximately 5-10 ml/kg of the ORS after each watery stool. The frequent passage of small unformed stools should not be confused with profuse watery diarrhea as it does not require fluid replacement.

Breastfeeding should be continued during the rehy dration phase. Refeeding must be initiated with starter F- 75 within 2-3 hr of starting rehydration. The feeds must be given on alternate hr (e.g. 2, 4, 6 hr) with reduced osmolarityORS (hr 1, 3, 5). Once rehydration is complete, feeding must be continued and ongoing losses replaced with ORS.

The progress of rehydration should be monitoredevery half hourly for first 2 hr and then hourly for the next 4- 10 hr. Pulse rate, respiratory rate, oral mucosa, urine frequency or volumeand frequency of stools and vomiting should be monitored. One must be alert for signs of overhydration (increaseinrespiratoryrateby 5/minute and pulse rate by 15/minute, increasing edema and periorbital

puffiness), which can be dangerous and may lead to heart failure. In case of signs of overhydration, ORS should be stopped immediately and child reassessed after one hour. On the other hand a decrease in the heart rate and respiratory rate (if increased initially) and increase in the urine output indicate that rehydration is proceeding. The return of tears, a moist oral mucosa, less sunken eyes and fontanelle and improved skin turgor are also indicators of rehydration. Once any four signs of hydration (child less thirsty, passing urine, tears, moist oral mucosa, eyes less sunken, faster skin pinch) are present, ORS for rehydration must bestoppedandcontinuedtoreplacetheongoinglosses.

Severe dehydration with shock It is important to recognize severe dehydration in malnourished children. Severedehydrationwithshockistreatedwithintravenous fluids. Ideally, Ringer lactate with 5% dextrose should be used as rehydrating fluid. If not available, half normal saline (N/2) with 5% dextrose or Ringer lactatealone can be used. After providing supplemental oxygen, the rehydrating fluid should be given at a slow infusion rate of 15ml/kgoverthefirsthour withcontinuousmonitoring of pulse rate, volume, respiratory rate, capillary refill time and urine output.

If there is improvement (pulse slows, faster capillary refill) at the end of the first hour of IV fluid infusion, a diagnosis of severe dehydration with shock should be considered and the rehydrating fluid repeated at the same rateof15ml/kgoverthenexthour. Thisshouldbefollowed by reducedosmolarityORS at 5-10 ml/kg/hr, either orally or by nasogastric tube. Patients should be monitored for features of overhydration and cardiac decompensation.

Septic shock If at the end of the first hour of IV rehydra tion, there is no improvement or worsening, septic shock must be considered and appropriate treatment started.

Step 4: Correct Electrolyte Imbalance

In severely malnourished children excess body sodium exists even though the plasma sodium may be low. Sodium intake should be restricted to prevent sodium overload and water retention during the initial phase of treatment. Excess sodium in the diet may precipitate congestive cardiac failure.

All severely malnourished children have deficiencies of potassium andmagnesium, which maytake two weeks or more to correct. Severely malnourished children may develop severe hypokalemia and clinically manifest with weakness of abdominal, skeletal and even respiratory muscles. This may mimic flaccid paralysis. Electro cardiographymayshow ST depression, T waves inversion and presence of U waves. If serum potassium is <2 mEq/1 or <3.5 mEq/1 with ECG changes, correction should be started at 0.3-0.5 mEq/kg/hr infusion of potassium chloride in intravenous fluids, preferablywithcontinuous monitoring of the ECG.

Once severe hypokalemia is corrected, all severely malnourished children need supplemental potassium at