Ghai Essential Pediatrics8th

.pdf

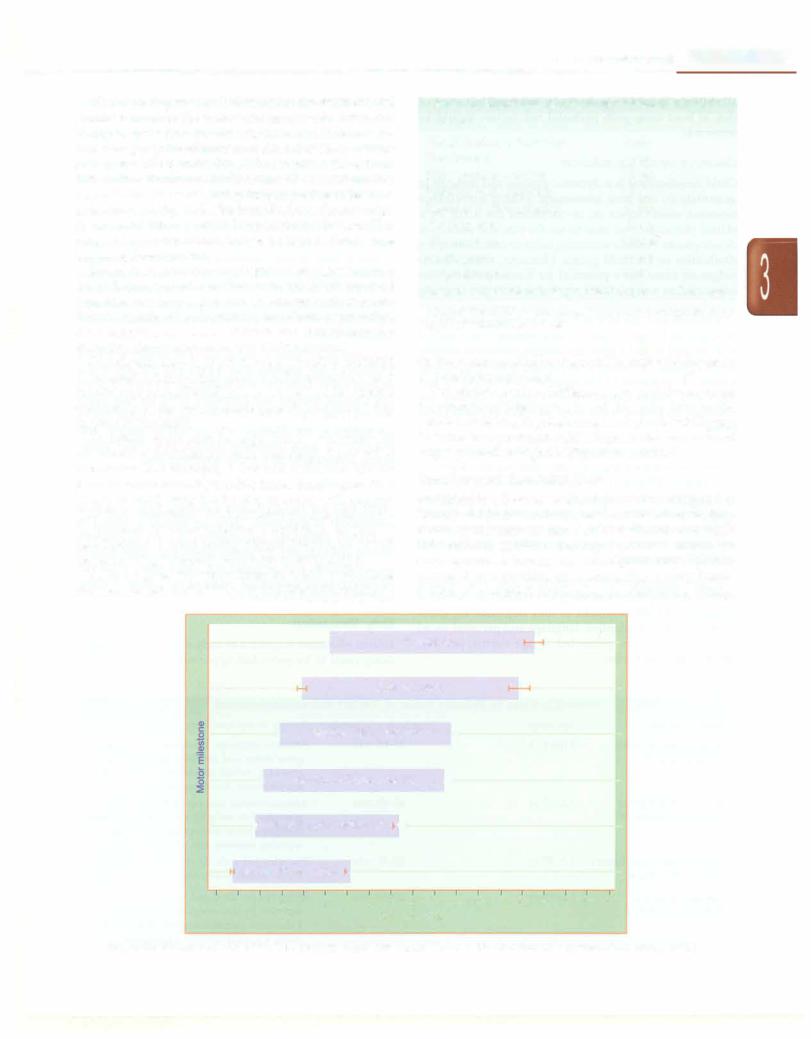

While drawing anyconclusionsaboutdevelopment, one should remember the wide variations in normality. For example, let us consider the milestone of standing alone. The average agefor attainment of this milestone in a WHO survey was 10.8 months (Fig. 3.42). However, the 3rd and 97thcentilesfor normalchildrenwere 7.7 and15.2months, respectively. The same is true for many other milestones as is shown in Fig. 3.42. The bars illustrate the age range for normal children toattain thatparticularmilestone.This range of normalcy should always be kept in mind while assessing development.

Retardation should not be diagnosed or suggested on a singlefeature. Repeatexaminationis desirable in any child who does not have a gross delay. Factors such as recent illness, significant malnutrition, emotional deprivation, slow maturation, sensory deficits and neuromuscular disorders should always be taken into account.

One should keep in mind the opportunities provided to the child to achieve that milestone. For example, a child who has not been allowed to move around on the ground sufficiently by the apprehensive parents may have delay in gross motor skills.

At times, there can be significant variations in attainment of milestones in individual fields, this is called dissociation. For example, a 1-yr-old child who speaks 2-3 words with meaning andhas finger thumb opposition (10-12 months), may not be able to stand with support (less than 10 months). Such children require evaluation for physical disorder affecting a particular domain of development. A child having normal development in all domains except language may have hearing deficit.

Table 3.5 gives the upper limits by which a milestone mustbe attained. Achild whodoes notattainthe milestone

o_e_v_e_io_p_m_e_n_t

Table 3.5: Upper limit of age for attainment of milestone

Milestone |

Age |

Visual fixation or following |

2mo |

Vocalization |

6mo |

Sitting without support |

lOmo |

Standing with assistance |

12mo |

Hands and knees crawling |

14mo |

Standing alone |

17mo |

Walking alone |

18mo |

Single words |

18mo |

Imaginative play |

3 yr |

Loss of comprehension, single words or phrases at any age

Adapted from WHO; MGRS group, WHO motor development study. Acta Pediatrics 2006;450:86-95

by the recommended limit should be evaluated for cause of developmental delay.

Thepredictivevalueofdifferentdomains ofdevelopment for subsequent intelligence is not the same. Fine motor, personal-social andlinguisticmilestonespredictintelligence far better than grossmotor skills. Inparticular, an advanced language predicts high intelligence in a child.

Development Screening Tests

Screening is a brief assessment procedure designed to identify children who should receive more intensive diag nosis or assessment. Such an assessment aids early intervention services, making a positive impact on development, behavior and subsequent school perfor mance. It also provides an opportunity for early identi fication of comorbid developmental disabilities. Ideally,

H |

Walking alone |

Standing alone

|

1--,1 |

Walking with assistance |

|

||

H |

|

Hands and knees crawling |

-l |

||

t-. |

Standing with assistance |

-t |

|

||

Sitting without support |

_. |

|

|

||

3 4 S |

6 |

7 8 |

9 10 |

11 12 |

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

|

|

|

Age jn months |

||

Fig. 3.42: Windows of achievement of six major motor milestones (WHO; Multicenter Growth Reference Study Group, 2006)

__E_s_s_e_n_t _ia_i_P_e_d_ i_at_ri_cs_________________________________

all children should be periodically screened but short of this, at least those with perinatal risk factors should be screened.

Developmental SuNeil/ance

Child development is a dynamic process and difficult to quantitate by one time assessment. During surveillance repeated observations on development are made by a skilled physician over time to see the rate and pattern of development. Periodic screeninghelpsto detect emerging disabilities as the child grows. However, using clinical judgment alone has a potential for bias and it has been suggested to use periodic screening tools for ongoing developmental surveillance. The physicianshouldchoose a standardized developmental screening tool that is practical and easy to use in office setting. Once skilled with thetool,it canbe used asscreeningmethodto identify at risk children. Screening tests popular in the west include Parents' Evaluations of Development Status (PEDS) and Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ). Some of the common screening tools used in India are described below.

Phatak's Baroda screening test This is India's best knowndevelopmenttestingsystemthatwas developed by Dr Promila Phatak. It is meant to be used by child psychologists rather than physicians. It is the Indian adaptation of Bayley's development scale and is applied tochildrenup to 30 months. It requiresseveraltestingtools and objects that are arranged according to age. The kit is available commercially.

Denver development screening test The revised Denver development screening test (DOST) or Denver II assesses child development in four domains, i.e. gross motor, fine motor adaptive, language and personal social behavior, which are presented as age norms, just like physical growth curves.

Trivandrum development screening chart This simplified adaptation of the Baroda development screen ing system is applicable to children up to 2 yr of age. It consists of 17 items selected from Bayley Scale of infant development (BSID) and Baroda tests. It is a simple test that can be administered in 5 min by a health worker, and

is useful as a mass screening test.

Clinical adaptive test and clinical linguistic and auditory milestone scale (CAT/CLAMS) This easy to

learn scale can be used to assess the child's cognitive and language skills. It uses parental report and direct testing of the child's skills.It is usedat ages of 0-36months and takes 10-20 min to apply. It is useful in discriminating children withmentalretardation(i.e.bothlanguageandvisualmotor delay) and those with communication disorders (low

language scores).

Goodenough-Harrisdrawingtest Thissimplenonverbal intelligence test requires only a pencil or pen and white unlinedpaper. Here the child is asked to draw a man in the best possible manner and points are given for each detail that the child draws. One can determine the mental age by comparing scores obtained with normative sample. This test allows a quick but rough estimate of a child's intelli gence, and is useful as a group screening tool.

Definitive Tests

These tests are required once screening tests or clinical assessment is abnormal. They are primarily aimed to accurately define the impairments in both degree and sphere. For example, by giving scores for verbal, perfor mance abilities and personal and social skills, these can be differentially quantified. Some of the common scales used are detailed in Table 3.6.

Early Stimulation

Infantswho show suspected orearly signs of development delay need to be provided opportunities that promote

Table: 3.6: Scales for definitive testing of intellect and neurodevelopment

Name ofthe test |

Age range |

Time taken to administer |

Scoring details; comments |

Bayley scale for infant |

1 mo to 3.5 yr |

30-60 min |

Assesses language, behavior, fine motor |

development II |

|

|

gross motor and problem solving skills; |

|

|

|

provides mental development index and |

|

|

|

psychomotor developmental index |

Wechsler intelligence |

6 to 17 yr |

65-80 min |

Assesses verbal and performance skills |

scale for children IV |

|

|

provides full scale IQ and indices of verbal |

|

|

|

comprehension perceptual reasoning, |

|

|

|

working memory and processing speed |

Stanford-Binet intelligence |

2 to 85 yr |

50-60 min |

Provides full scale IQ, verbal IQ, nonverbal |

scales, 5th edition |

|

|

IQ, 10 subset scores and 4 composite scores |

Vineland adaptive |

O to 89 yr |

20-60 min |

Measures personal and social skills as |

behavior scale II |

|

|

reported by the caregiver or parent, in |

|

|

|

4 domains (communication, daily living |

|

|

|

skills, socialization and motor skills) |

___________________________________D_ve_eio_ep__nm t

body control, acquisition of motor skills, language development and psychosocial maturity. These inputs, termed early stimulation, include measures such as making additional efforts to make the child sit or walk, givingtoys to manipulate,playingwith thechild, showing objects, speaking to the child and encouraging him to speak andpromptingthe child to interact withothers, etc.

There is a general lack of evidence for effectiveness of these early interventions in improving neurodevelop mentaloutcome and motor abilities. However, studies in premature babies, cerebral palsy, institutionalized child ren and other children at high risk for adverse neuro developmental outcomes suggest that these interventions are effective if started early. Compliance to interventions is important for favorable results on neurodevelopment. Systematic reviews suggest that the effect of these interventions is sustained in later childhood. For example, play and reading were effective in earlychildhood in low and middle-income countries, and kangaroo mother care was effective for low birth weight babies in resource poor settings.

Promoting Development by Effective Parenting

Comprehensive care to children requires focus on preventive efforts including child-rearing information to parents. Parenting has an immense impact on emotional, social and cognitive development and also plays a role in the later occurrence of mental illness, educational failure and criminal behavior. Creating the right conditions for early childhood development is likely to be more effective and less costly than addressing problems at a later age.

Television Viewing and Development

Television viewing in younger children has been shown to retard language development. It is a passive mode of entertainment and impairs children's ability to learn and read, and also limits creativity. Children can pick up inappropriate language and habitsby watching TVshows andcommercials. Violence andsexualityon televisioncan have alastingimpact on the child's mind. Parents need to regulate both the quantity and quality of TV viewing, limiting the time to 1-2 hr per day and ensuring that the content they see is useful.

Some Useful Internet Resources

http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/child development. html http://kidshealth.org/parent/growth/ http://www.nichd.nih.gov/ http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/ http://www.bridges4kids.org/disabilities/SU.html http://www.zerotothree.org/

Suggested Reading

Developmental surveillance and screening of infants and young chil dren. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. Pediatrics 2001;108:192---6

Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, et al. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the de veloping world. Lancet 2007;369:229-42

Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung Y, Cueto S, et al. Developmental potential in the first 5 yr for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:60-70

BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

Anorexia Nervosa

This eating disorder is characterized by: (i) body weight <85% of expected weight for age and height; (ii) intense fear of becoming fat even though underweight; (iii) disturbed body image and denial that the current body weight is low; and, (iv) in postmenarcheal girls, amenor rhea. It is most common among 15-19-yr-old.

Two clinicalsubtypesare recognized. Somepatientslose weight through excessive dietary restrictions and increased physical activity (restricting type), while others resort to vomiting and the use of laxatives or diuretics. Anorexia is commonly associated with depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and/or obsessive compulsive disorder. Profoundweightloss mayresult in hypothermia, hypotension, dependent edema, bradycardia and metabolic changes. Hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis may occur due to vomiting and use of diuretics or purgatives. Mortality is attributed to cachexia and suicide.

Psychotherapy, including individual and family the rapy, and in some cases, group therapy, are required to establish appropriate eating patterns and restore normal perceptions of hunger and satiety. A nurturing emotional environment is essential. Severely undernourished patients require nutritional rehabilitation targeting normal weight for height. While oral supervised feeding is preferred, some patients require nasogastric or parenteral nutrition. Antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs are prescribed as required.

Bulimia

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by (i) recurrent episodes of binge eating characterized by eating in a discrete period of time an amount of food that is definitely more than what normalindividualseat during a similar time period, without control over eating during the episode; and (ii) recurrent inappropriate compensatorybehaviorto prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, fasting, or excessive exercise. Binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behavior both occur, on average, at least twice a week for 3 months. There is undue influence of body shape and weight on self-evaluation. The disorder ismorecommonamonggirls between 10-19 yr of age. Many affected patients have comorbidities like depression and other psychoses. Management includes a combination of psychotherapy (specifically, cognitivebehaviortherapy)and anti-depres sant medications (such as fluoxetine). Active followup

__Ess e_nt_iai_Pe_di_at_rics__________________________________ _

needs to be maintained to ensure motivation and adhe rence to therapy.

Pica

Pica is the persistent ingestion of non-nutritive substances such as plaster, charcoal, paint and earth for at least 1 month in a manner that is inappropriate for the develop mental level, is not part of a culturally sanctioned practice and is sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention. It is a common problem in children less than 5 yr of age. Factors speculated to predispose to pica include mental retardation, psychosocial stress (maternal deprivation, parental neglect and abuse) and other beha vioral disorders. Poor socioeconomic status, malnutrition and iron deficiency are commonly associated with pica but their etiologic significance has not been established. Children with pica are at an increased risk for lead poison ing, iron deficiency anemia and parasitic infestations. Management comprises behavior modification, alleviating the psychosocial stress if any, and iron supplementation if deficiency is present.

Food Fussiness

Food fussiness is a common problem in young children. It often reflects an excessive need for control on the part of the parents about what the child eats. Management involves examining the child for any nutritional deficiencies and counseling the parents regarding the nor mal growth pattern and dietary requirements of children. Useful behavioral strategies include establishing regular meal timings, ensuring a pleasant atmosphere, offering a variety of foods and setting an example of enjoying the same food themselves. Offering small servings at a time, reducing between meal caloric intake, not force feeding the child, presenting the food in an interesting manner and praise for good eating behavior are other helpful strategies. Parents should resist the temptation of offering sugary or fatty snacks as substitute or reward for eating healthy food.

Difficulties with Toilet Training

Refusal to defecate in the toilet with development of constipation is a common problem in children and is a cause for parental frustration and increased stress for the child. The most common setting is a power struggle between the child and parents ensuing from toilet training that is begun before the child is developmentally ready to be trained. Toilet training should be started after 2 yr of age, when the child has spontaneously started indicating bladder and bowel fullness, and is able to follow simple instructions. The general ambience should be conducive to learning and free from pressure. Use of a toddler-size seat that can be placed on top of the regular toilet seat helps the child feel more secure and not afraid of falling in. Consistency in the parents' approach and positive reinforcement help in achieving the normal pattern.

Temper Tantrums

Temper tantrums include behaviors that occur when the child responds to physical or emotional challenges by drawing attention to himself and can include yelling, biting, crying, kicking, pushing, throwing objects, hitting and head banging. Tantrums typically begin at 18-36 months of age. Inability to assert autonomy or perform a complex task on his/her own causes frustration to the child which cannot be effectively communicated due to limited verbal skills. The frustration therefore is acted out as undesired behaviors. Such behavior peaks during second and third year of life and gradually subsides by the age of 3-6 yr as the child learns to control his negativism.

Parents should be asked to list situations where disruptive behavior are likely to occur and plan strategies to avoid these. For example, they should ensure that the child is rested and fed, and should carry a snack for the child when going for an outing. During a tantrum, the parents' behavior should be calm, firm and consistent and they should not permit the child to take advantage from suchbehavior. The child should be protected from injuring himself or others. At an early stage, distracting his attention from the immediate cause and changing the environment can abort the tantrum. A 'time out', i.e. asking the child to stay alone in a safe and quiet place for a few minutes, is useful.

Breath Holding Spells

Breath holding spells are reflexive events typically initiated by a provocative event that causes anger, frustration or pain causing the child to cry. The crying stops at full expiration and the child becomes apneic and cyanotic or pale. In some cases the child may lose consciousness, become hypotonic and fall. If the spell lasts for more than a few seconds, brief tonic-clonic seizure may occur. Breath holding spells always revert on their own within several seconds, with the child resuming normal activity or falling asleep for some time. Breath holding spells are rare before 6 months of age, peak at 2 yr and abate by 5 yr of age.

Diagnosis is based on the setting and the typical seq uence of crying, cyanosis or pallor with or without brief loss of consciousness. The differential diagnoses include seizures, cardiac arrhythmias or brainstem malformation. The history of provoking event, stereotyped pattern of events and presence of color change preceding the loss of consciousness help in distinguishing breath holding spells from seizures. In case the spells are associated with pallor, an electrocardiogram may be done to rule out cardiac arrhythmias and long QT syndrome.

After a thorough examination of the child, the parents should be reassured. They are explained that the apneic spells are always self-limited and do not lead to brain injury or death. The family should be advised to be consistent in their behavior with the child, remaining calm