новая папка / [libribook.com] 50 Cases in Clinical Cardiology_ A Problem Solving Approach 1st Edition

.Pdf

Case 29 Aortic Valve Endocarditis |

|

135 |

|

|

|

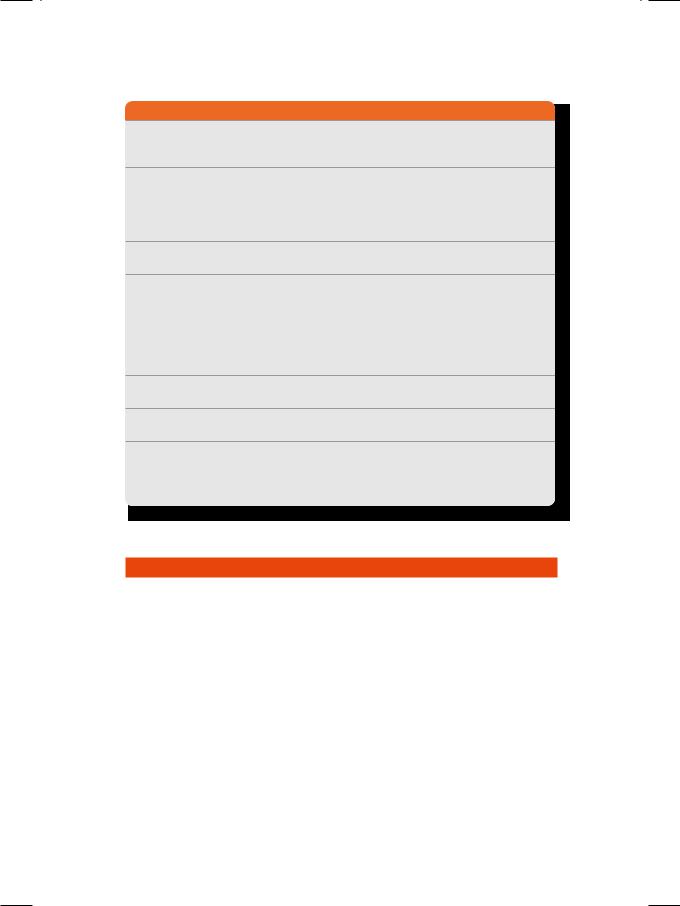

Table 29.2: Modified Duke’s diagnostic criteria of infective endocarditis

Pathological criteria

• Micro-organism demonstrated by bacterial culture • Active endocarditis on histological examination

Major criteria

• Positive blood cultures

• Typical organism consistent with endocarditis, on two separate blood cultures • Organism consistent with endocarditis, from persistently positive blood culture • Positive serology for Coxiella burnetti, Chlamydia psitacci or Mycoplasma

Evidence of endocardial involvement

• Prosthetic valve dehiscence, aortic root abscess, new valvular regurgitation

Minor criteria

• Predisposing heart condition e.g. prosthetic heart valve or intravenous drug use • Fever more than 380C

• Vascular phenomenon (embolic complication, mycotic aneurysm, Janeway lesions) • Immunological phenomenon (rheumatoid factor, nephritis, Osler’s nodes, Roth spots) • Microbiological evidence not meeting major criteria

• Echocardiographic changes not meeting major criteria

DEFINITE ENDOCARDITIS

• Pathological criteria plus 2 major, or 1 major and 3 minor, or 5 minor criteria

POSSIBLE ENDOCARDITIS

• 1 major and 1 minor, or 3 minor criteria

REJECTED DIAGNOSIS

• Firm alternative diagnosis • Does not meet above criteria

• Resolution within 4 days of antibiotic therapy

MANAGEMENT ISSUES

The mainstay of the effective treatment of infective endocarditis (barring fungal endocarditis) is antibacterial drugs. Bactericidal drugs with low minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC90) against the identified organism are chosen. The intravenous route of administration is preferable to achieve high serum levels of the drug. This ensures adequate penetration of the antibiotic, since the vegetations are rich in necrotic tissue debris and therefore resist entry of the drug. A combination of 3rd generation cephalosporin with an aminoglycoside may be initiated, even when culture reports are pending, and are generally effective against Streptococcal endocarditis. Infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus is treated with flucloxacillin or vancomycin along with gentamycin or amikacin. Usually 2 to 4 weeks of treatment suffices in native valve Streptococcal infection while 6 weeks are required to treat Staphylococcal prosthetic valve endocarditis. The indications for surgical intervention in endocarditis are prosthetic valve dehiscence, aortic root abscess, fistula formation, refractory heart failure and recurrent embolic events (Table 29.3).

136 |

|

Section 9 Endocardial Infections |

|

|

|

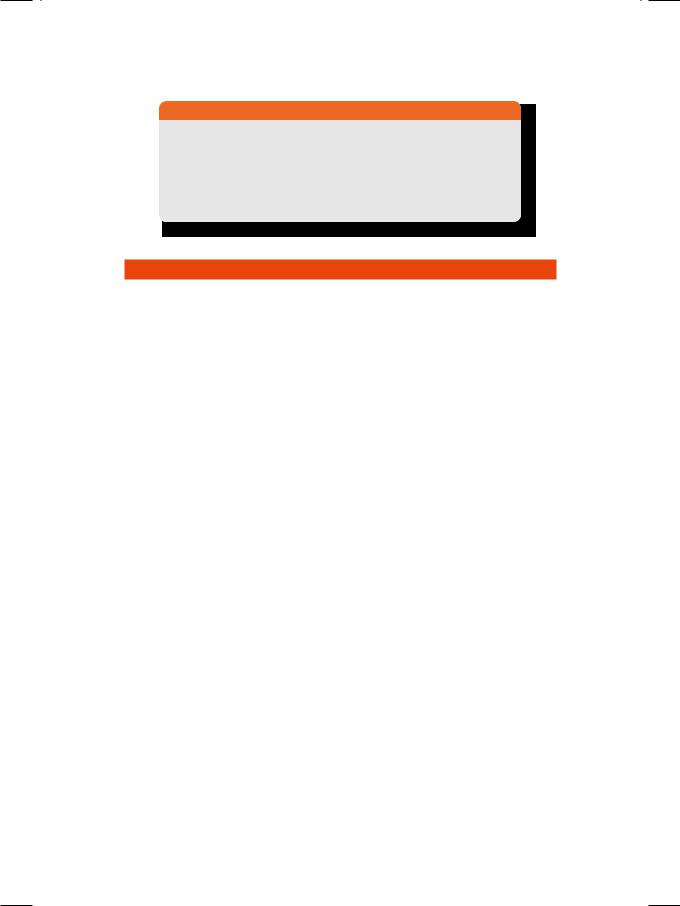

Table 29.3: Indications for surgery in endocarditis

• Fungal or resistant organism causing endocarditis • Prosthetic valve dehiscence or aortic root abscess • Heart block (septal abscess) or a fistula formation

• Valve regurgitation leading to refractory heart failure • Recurrent systemic emboli despite adequate therapy

RECENT ADVANCES

The clinical spectrum of infective endocarditis has undergone a major change in the last two decades, for several reasons. Prevalence of Staphylococcal infection has increased with the widespread use of catheters, venous lines and pacing leads and the rising incidence of intravenous drug abuse. An entirely new HACEK group of bacteria has been identified as also a range of intracellular bacteria that can cause endocarditis. With the growing number of valve replacements, prosthetic valve endocarditis is on the rise. Finally, immunocompromised hosts such as HIV-infected patients and organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive drugs are more likely to be infected by fungal organisms.

|

|

C A S E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

30 |

Tricuspid Valve |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Endocarditis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year old male came to the out-patient department of a charitable hospital, with history of fever for the last 3 weeks. The fever was high-grade and associated with chills and night sweats, but there were no rigors. He also felt fatigued and had lost his appetite, leading to significant weight loss. However, he was not aware of his exact past body-weight. He also had cough with scanty mucoid sputum for one month, but there was no history of burning micturition, vomiting, pain abdomen or passing loose stools. There was also no history of dyspnea, chest pain or hemoptysis. The patient was unmarried and he was not accompanied by any attendant. He was a college drop-out, presently not engaged in any gainful employment. He admitted smoking and taking alcohol as well as drug-snorts, whenever he could afford them. He also sometimes abused intravenous illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient was emaciated, ill-looking, confused and febrile. The pulse rate was 110 beats/min. with a BP of 96/70 mm Hg and a temperature of 101.60F. He was mildly anemic but not cyanosed or icteric and there was pitting edema over the ankles. The neck veins were engorged and showed rapid y descent. There were multiple needle-prick marks over the veins on his forearms. On cardiac auscultation, a pansystolic murmur was heard over the lower left parasternal area; no gallop sound was audible. There were scattered rhonchi and crepts over the lung fields. On examination of the abdomen, there was hepatomegaly. The liver edge was palpable 5 cm below the costal margin and it was pulsatile. There was no splenomegaly or ascites.

PERTINENT INVESTIGATIONS

The hemoglobin was 9.2 g/dL with a total leucocyte count of 13,600/cumm. of which 78% were neutrophils; the ESR was 64 mm in the 1st hour. Urine analysis showed albumin +1 with 2-3 WBCs and 8-10 RBCs per high power field. ASLO titre was 110 IU with a CRP value of 62 mg/L. The biochemical parameters were Glucose 78 mg/dl, Creatinine 1.4 mg/dl, Bilirubin 1.8mg/dl, SGOT 79 and SGPT 53 and Cholesterol 144 mg/dl. The hepatitis B surface antigen was negative but his HIV-status was unknown. Urine culture did not yield any bacterial growth. Throat swab culture was negative for beta-hemolytic Streptococcus. Three sets

138 |

|

Section 9 Endocardial Infections |

|

|

|

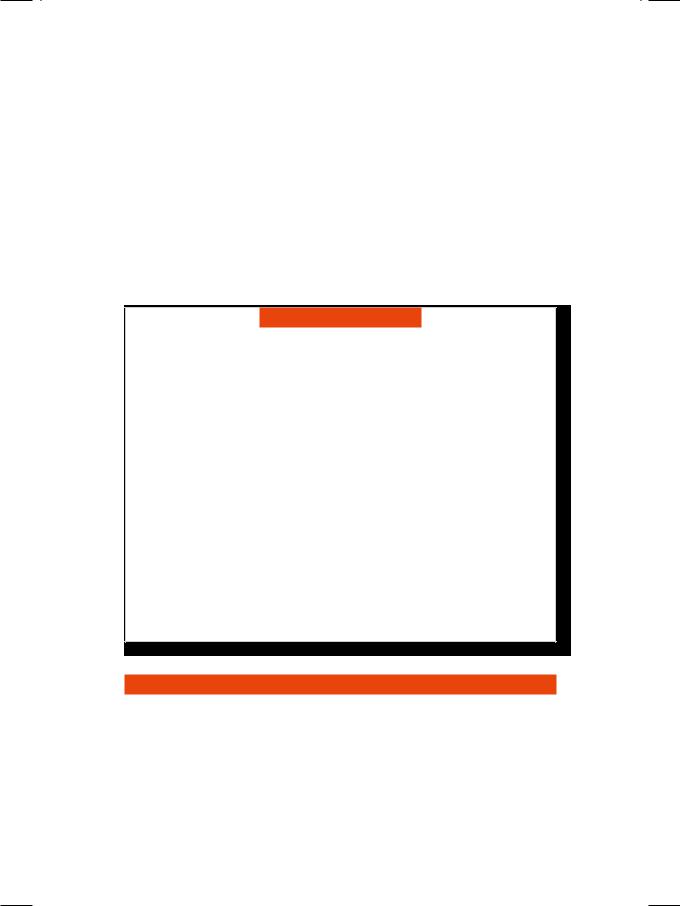

Figure 30.1: ECHO showing a nodular mass attached to valve leaflet

of blood cultures were obtained, including from the veins of the forearms that bore needle-prick marks. Two out of the three cultures grew coagulase negative Staphylococcus aureus. One of the cultures grew Candida albicans.

ECG showed sinus tachycardia with narrow QRS complexes and no ST-T changes. X-ray chest did not show any cardiomegaly, but the broncho-vascular markings were prominent over both lung fields. ECHO revealed normal left ventricular size and ejection fraction. The mitral and aortic valves were normal. An irregular echo-reflective mass was observed, which appeared to arise from the tricuspid valve (Fig. 30.1). There was moderate degree of tricuspid regurgitation. Keeping in mind the history of a prolonged febrile illness with intravenous drug abuse, positive blood cultures and demonstrable vegetations with tricuspid regurgitation, the most likely diagnosis in this case was of tricuspid valve endocarditis.

CLINICAL DISCUSSION

Endocarditis of the left-sided cardiac valves is more common than that of the rightsided valves. This is because of greater turbulence of blood flow in the left side of the heart and the fact that mitral and aortic valve disease is far more common than tricuspid valve disease. Tricuspid valve endocarditis usually occurs due to intravenous drug abuse. Staphylococcal aureus introduced by contaminated needles from the skin into the venous system, is the most common causative organism (Table 30.1).

Table 30.1: Pathogens implicated in right-sided endocarditis

• |

Typical |

Staphylococcus aureus |

|

|

|

• |

Atypical |

HACEK* group bacteria |

|

|

|

• |

Fungal |

Candida, Aspergillus |

|

|

|

*HACEK group: Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella

Case 30 Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis |

|

139 |

|

|

|

Table 30.2: Masses in right atrium

• Right atrial thrombus • Right atrial myxoma • Tricuspid vegetation • Metastatic deposits

• Chiari network remnant • Eustachian valve of IVC*

* IVC: Inferior Vena Cava

In an immuno-compromised host, HACEK group bacteria and fungal pathogens may be implicated, as in our case. Fungal endocarditis causes large vegetations, which produce a mass in the right atrium. Other causes of a mass in the right atrium are thrombus, myxoma and metastasis (Table 30.2). Tumors that grow along the blood vessels, such as hypernephroma of the kidney and hepatocellular carcinoma, extend to the right atrium via the inferior vena cava.

The Duke’s diagnostic criteria are popularly used for the definite diagnosis of endocarditis. Major criteria are microbiological and echocardiographic criteria. Microbiological evidence is positive blood culture or bacterial serology, of a typical organism consistent with endocarditis. Echocardiographic evidence is endocardial involvement in the form of an oscillating valvular structure or new valvular regurgitation (Table 30.3).

Table 30.3: Diagnostic criteria of infective endocarditis

Microbiological |

• |

positive blood culture |

|

|

|

|

• |

positive bacterial serology |

|

|

|

Echocardiographic |

• |

oscillating valvular structure |

|

|

|

|

• |

new valvular regurgitation |

|

|

|

MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Antimicrobial agents are the mainstay of treatment of infective endocarditis. A bactericidal drug with a low MIC90 value against the identified organism is chosen and given intravenously in full doses for an adequate period of time. For Staphylococcal infection, flucloxacillin along with gentamycin is the preferred regimen. For fungal infection, itraconazole or liposomal amphotericin B is chosen. Both these regimens are followed for 4 to 6 weeks. Septic pulmonary emboli which can turn into lung abscess, are treated with antimicrobial drugs and not by anticoagulants.

140 |

|

Section 9 Endocardial Infections |

|

|

|

RECENT ADVANCES

The incidence of Staphylococcal endocarditis has risen due to the widespread use of catheters, venous lines and pacing leads. Methicillin resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) has emerged as a notorious pathogen. Fungal endocarditis is been recognized in immunocompromised hosts such as HIV-infected patients and organ-transplant recipients on immunosuppressive drugs.

S E C T I O N

10

Intracardiac

Masses

|

|

C A S E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

31 |

Atrial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Myxoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CASE PRESENTATION

A 42-year old woman presented to the out-patient department with frequent fainting spells in the preceding two weeks, against a background history of exertional breathlessness. Besides being dyspneic, she had felt fatigued and lethargic over the last 3 months. She had also noticed a low-grade fever and an unintentional weight loss of 4 kg in this period. She gave no history of chills, rigors, night-sweats or nocturnal dyspneic episodes. There was no history of cyanotic spells, squatting attacks or fleeting joint pains during her childhood. She denied smoking tobacco, consuming alcohol or abusing illicit drugs.

On examination, she was mildly pale and dyspneic, but not in any distress. Her heart rate was 96 beats/min. with a BP of 128/84 mm Hg and her temperature was 99.8°F. There were no signs of congestive heart failure. On auscultation, a middiastolic rumble was heard at the mitral area, preceded by a high-pitched third heart sound. The intensity and character of the murmur changed with the patient’s position. There were no crepitations over the lung fields.

CLINICAL DISCUSSION

A history of dyspnea, constitutional symptoms and febrile illness with a cardiac murmur, raises several diagnostic possibilities. These are:

•Rheumatic fever

•Infective endocarditis

•Connective tissue disorder

•Occult malignant disease

•Atrial myxoma.

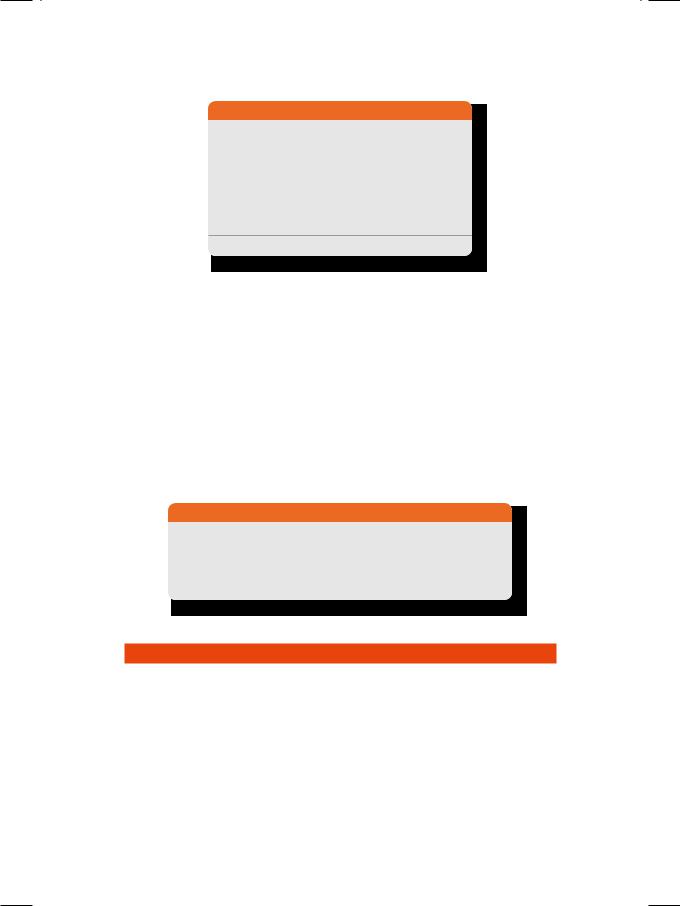

The most likely reason for a mid-diastolic murmur in the mitral area is rheumatic mitral stenosis. The murmur is preceded by an opening snap, if the leaflets are pliable. The murmur is best audible with the patient in the left lateral position but does not change its character. ECG and X-ray chest of this patient were unremarkable. ECHO revealed a round mobile mass in the left atrium, arising from the fossa ovalis of the inter-atrial septum and prolapsing into the mitral valve orifice (Fig. 31.1). The mass was lobulated in outline and variegated

144 |

|

Section 10 Intracardiac Masses |

|

|

|

Figure 31.1: ECHO showing left atrial myxoma prolapsing into the mitral orifice

in echogenicity. The left atrium was mildly dilated but the mitral valve leaflets were normal in structure and excursion. This appearance was highly suggestive of an atrial myxoma.

Anatrialthrombuscloselyresemblesamyxomawithcertainsubtledifferences.

The thrombus arises from the posterior atrial wall, not the septum and it is never pedunculated. A myxoma is usually pedunculated and rarely sessile. Myxoma generally prolapses into the mitral valve orifice in diastole (Fig. 31.2), unless it is too large in size or sessile. Thrombus is fairly rounded in outline and uniform in echogenicty, while a myxoma is often lobulated and variegated in appearance due to areas of hemorrhage, cystic necrosis and calcification. Moreover, a left atrial thrombus is often associated with structural abnormality of the mitral valve.

The differences between an atrial myxoma and an atrial thrombus are given in Table 31.1. Besides an atrial myxoma and an atrial thrombus, other structures that may be rarely seen in the left atrium are supravalvular ring (cor triatriatum), dilated coronary sinus, anomalous pulmonary veins, and large mitral leaflet vegetations.

Figure 31.2: Figure showing left atrial myxoma (A), prolapsing into the mitral orifice (B) RV: Right ventricle; LV: Left ventricle; AV: Aortic valve; MV: Mitral valve; AO: Aorta; LA: Left atrium