- •List of Tables

- •List of Figures

- •Table of Notation

- •Preface

- •Boolean retrieval

- •An example information retrieval problem

- •Processing Boolean queries

- •The extended Boolean model versus ranked retrieval

- •References and further reading

- •The term vocabulary and postings lists

- •Document delineation and character sequence decoding

- •Obtaining the character sequence in a document

- •Choosing a document unit

- •Determining the vocabulary of terms

- •Tokenization

- •Dropping common terms: stop words

- •Normalization (equivalence classing of terms)

- •Stemming and lemmatization

- •Faster postings list intersection via skip pointers

- •Positional postings and phrase queries

- •Biword indexes

- •Positional indexes

- •Combination schemes

- •References and further reading

- •Dictionaries and tolerant retrieval

- •Search structures for dictionaries

- •Wildcard queries

- •General wildcard queries

- •Spelling correction

- •Implementing spelling correction

- •Forms of spelling correction

- •Edit distance

- •Context sensitive spelling correction

- •Phonetic correction

- •References and further reading

- •Index construction

- •Hardware basics

- •Blocked sort-based indexing

- •Single-pass in-memory indexing

- •Distributed indexing

- •Dynamic indexing

- •Other types of indexes

- •References and further reading

- •Index compression

- •Statistical properties of terms in information retrieval

- •Dictionary compression

- •Dictionary as a string

- •Blocked storage

- •Variable byte codes

- •References and further reading

- •Scoring, term weighting and the vector space model

- •Parametric and zone indexes

- •Weighted zone scoring

- •Learning weights

- •The optimal weight g

- •Term frequency and weighting

- •Inverse document frequency

- •The vector space model for scoring

- •Dot products

- •Queries as vectors

- •Computing vector scores

- •Sublinear tf scaling

- •Maximum tf normalization

- •Document and query weighting schemes

- •Pivoted normalized document length

- •References and further reading

- •Computing scores in a complete search system

- •Index elimination

- •Champion lists

- •Static quality scores and ordering

- •Impact ordering

- •Cluster pruning

- •Components of an information retrieval system

- •Tiered indexes

- •Designing parsing and scoring functions

- •Putting it all together

- •Vector space scoring and query operator interaction

- •References and further reading

- •Evaluation in information retrieval

- •Information retrieval system evaluation

- •Standard test collections

- •Evaluation of unranked retrieval sets

- •Evaluation of ranked retrieval results

- •Assessing relevance

- •A broader perspective: System quality and user utility

- •System issues

- •User utility

- •Results snippets

- •References and further reading

- •Relevance feedback and query expansion

- •Relevance feedback and pseudo relevance feedback

- •The Rocchio algorithm for relevance feedback

- •Probabilistic relevance feedback

- •When does relevance feedback work?

- •Relevance feedback on the web

- •Evaluation of relevance feedback strategies

- •Pseudo relevance feedback

- •Indirect relevance feedback

- •Summary

- •Global methods for query reformulation

- •Vocabulary tools for query reformulation

- •Query expansion

- •Automatic thesaurus generation

- •References and further reading

- •XML retrieval

- •Basic XML concepts

- •Challenges in XML retrieval

- •A vector space model for XML retrieval

- •Evaluation of XML retrieval

- •References and further reading

- •Exercises

- •Probabilistic information retrieval

- •Review of basic probability theory

- •The Probability Ranking Principle

- •The 1/0 loss case

- •The PRP with retrieval costs

- •The Binary Independence Model

- •Deriving a ranking function for query terms

- •Probability estimates in theory

- •Probability estimates in practice

- •Probabilistic approaches to relevance feedback

- •An appraisal and some extensions

- •An appraisal of probabilistic models

- •Bayesian network approaches to IR

- •References and further reading

- •Language models for information retrieval

- •Language models

- •Finite automata and language models

- •Types of language models

- •Multinomial distributions over words

- •The query likelihood model

- •Using query likelihood language models in IR

- •Estimating the query generation probability

- •Language modeling versus other approaches in IR

- •Extended language modeling approaches

- •References and further reading

- •Relation to multinomial unigram language model

- •The Bernoulli model

- •Properties of Naive Bayes

- •A variant of the multinomial model

- •Feature selection

- •Mutual information

- •Comparison of feature selection methods

- •References and further reading

- •Document representations and measures of relatedness in vector spaces

- •k nearest neighbor

- •Time complexity and optimality of kNN

- •The bias-variance tradeoff

- •References and further reading

- •Exercises

- •Support vector machines and machine learning on documents

- •Support vector machines: The linearly separable case

- •Extensions to the SVM model

- •Multiclass SVMs

- •Nonlinear SVMs

- •Experimental results

- •Machine learning methods in ad hoc information retrieval

- •Result ranking by machine learning

- •References and further reading

- •Flat clustering

- •Clustering in information retrieval

- •Problem statement

- •Evaluation of clustering

- •Cluster cardinality in K-means

- •Model-based clustering

- •References and further reading

- •Exercises

- •Hierarchical clustering

- •Hierarchical agglomerative clustering

- •Time complexity of HAC

- •Group-average agglomerative clustering

- •Centroid clustering

- •Optimality of HAC

- •Divisive clustering

- •Cluster labeling

- •Implementation notes

- •References and further reading

- •Exercises

- •Matrix decompositions and latent semantic indexing

- •Linear algebra review

- •Matrix decompositions

- •Term-document matrices and singular value decompositions

- •Low-rank approximations

- •Latent semantic indexing

- •References and further reading

- •Web search basics

- •Background and history

- •Web characteristics

- •The web graph

- •Spam

- •Advertising as the economic model

- •The search user experience

- •User query needs

- •Index size and estimation

- •Near-duplicates and shingling

- •References and further reading

- •Web crawling and indexes

- •Overview

- •Crawling

- •Crawler architecture

- •DNS resolution

- •The URL frontier

- •Distributing indexes

- •Connectivity servers

- •References and further reading

- •Link analysis

- •The Web as a graph

- •Anchor text and the web graph

- •PageRank

- •Markov chains

- •The PageRank computation

- •Hubs and Authorities

- •Choosing the subset of the Web

- •References and further reading

- •Bibliography

- •Author Index

19.3 Advertising as the economic model |

429 |

SEARCH ENGINE

OPTIMIZERS

ADVERSARIAL INFORMATION RETRIEVAL

LINK SPAM

on selected search keywords. When a browser requests the doorway page, it is redirected to a page containing content of a more commercial nature. More complex spamming techniques involve manipulation of the metadata related to a page including (for reasons we will see in Chapter 21) the links into a web page. Given that spamming is inherently an economically motivated activity, there has sprung around it an industry of Search Engine Optimizers, or SEOs to provide consultancy services for clients who seek to have their web pages rank highly on selected keywords. Web search engines frown on this business of attempting to decipher and adapt to their proprietary ranking techniques and indeed announce policies on forms of SEO behavior they do not tolerate (and have been known to shut down search requests from certain SEOs for violation of these). Inevitably, the parrying between such SEOs (who gradually infer features of each web search engine’s ranking methods) and the web search engines (who adapt in response) is an unending struggle; indeed, the research sub-area of adversarial information retrieval has sprung up around this battle. To combat spammers who manipulate the text of their web pages is the exploitation of the link structure of the Web – a technique known as link analysis. The first web search engine known to apply link analysis on a large scale (to be detailed in Chapter 21) was Google, although all web search engines currently make use of it (and correspondingly, spammers now invest considerable effort in subverting it – this is known as link spam).

?Exercise 19.1

If the number of pages with in-degree i is proportional to 1/i2.1, what is the probability that a randomly chosen web page has in-degree 1?

Exercise 19.2

If the number of pages with in-degree i is proportional to 1/i2.1, what is the average in-degree of a web page?

Exercise 19.3

If the number of pages with in-degree i is proportional to 1/i2.1, then as the largest in-degree goes to infinity, does the fraction of pages with in-degree i grow, stay the same, or diminish? How would your answer change for values of the exponent other than 2.1?

Exercise 19.4

The average in-degree of all nodes in a snapshot of the web graph is 9. What can we say about the average out-degree of all nodes in this snapshot?

19.3Advertising as the economic model

Early in the history of the Web, companies used graphical banner advertisements on web pages at popular websites (news and entertainment sites such as MSN, America Online, Yahoo! and CNN). The primary purpose of these advertisements was branding: to convey to the viewer a positive feeling about

Online edition (c) 2009 Cambridge UP

430 |

19 Web search basics |

the brand of the company placing the advertisement. Typically these adver- CPM tisements are priced on a cost per mil (CPM) basis: the cost to the company of having its banner advertisement displayed 1000 times. Some websites struck contracts with their advertisers in which an advertisement was priced not by the number of times it is displayed (also known as impressions), but rather by the number of times it was clicked on by the user. This pricing model is

CPC known as the cost per click (CPC) model. In such cases, clicking on the advertisement leads the user to a web page set up by the advertiser, where the user is induced to make a purchase. Here the goal of the advertisement is not so much brand promotion as to induce a transaction. This distinction between brand and transaction-oriented advertising was already widely recognized in the context of conventional media such as broadcast and print. The interactivity of the web allowed the CPC billing model – clicks could be metered and monitored by the website and billed to the advertiser.

The pioneer in this direction was a company named Goto, which changed its name to Overture prior to eventual acquisition by Yahoo! Goto was not, in the traditional sense, a search engine; rather, for every query term q it accepted bids from companies who wanted their web page shown on the query q. In response to the query q, Goto would return the pages of all advertisers who bid for q, ordered by their bids. Furthermore, when the user clicked on one of the returned results, the corresponding advertiser would make a payment to Goto (in the initial implementation, this payment equaled the advertiser’s bid for q).

Several aspects of Goto’s model are worth highlighting. First, a user typing the query q into Goto’s search interface was actively expressing an interest and intent related to the query q. For instance, a user typing golf clubs is more likely to be imminently purchasing a set than one who is simply browsing news on golf. Second, Goto only got compensated when a user actually expressed interest in an advertisement – as evinced by the user clicking the advertisement. Taken together, these created a powerful mechanism by which to connect advertisers to consumers, quickly raising the annual revenues of Goto/Overture into hundreds of millions of dollars. This style of search en-

SPONSORED SEARCH gine came to be known variously as sponsored search or search advertising.

SEARCH ADVERTISING Given these two kinds of search engines – the “pure” search engines such as Google and Altavista, versus the sponsored search engines – the logical next step was to combine them into a single user experience. Current search engines follow precisely this model: they provide pure search results

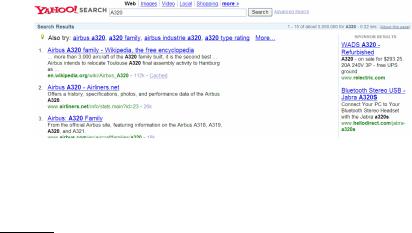

ALGORITHMIC SEARCH (generally known as algorithmic search results) as the primary response to a user’s search, together with sponsored search results displayed separately and distinctively to the right of the algorithmic results. This is shown in Figure 19.6. Retrieving sponsored search results and ranking them in response to a query has now become considerably more sophisticated than the simple Goto scheme; the process entails a blending of ideas from information

Online edition (c) 2009 Cambridge UP

19.3 Advertising as the economic model |

431 |

SEARCH ENGINE MARKETING

CLICK SPAM

Figure 19.6 Search advertising triggered by query keywords. Here the query A320 returns algorithmic search results about the Airbus aircraft, together with advertisements for various non-aircraft goods numbered A320, that advertisers seek to market to those querying on this query. The lack of advertisements for the aircraft reflects the fact that few marketers attempt to sell A320 aircraft on the web.

retrieval and microeconomics, and is beyond the scope of this book. For advertisers, understanding how search engines do this ranking and how to allocate marketing campaign budgets to different keywords and to different sponsored search engines has become a profession known as search engine marketing (SEM).

The inherently economic motives underlying sponsored search give rise to attempts by some participants to subvert the system to their advantage. This can take many forms, one of which is known as click spam. There is currently no universally accepted definition of click spam. It refers (as the name suggests) to clicks on sponsored search results that are not from bona fide search users. For instance, a devious advertiser may attempt to exhaust the advertising budget of a competitor by clicking repeatedly (through the use of a robotic click generator) on that competitor’s sponsored search advertisements. Search engines face the challenge of discerning which of the clicks they observe are part of a pattern of click spam, to avoid charging their advertiser clients for such clicks.

?Exercise 19.5

The Goto method ranked advertisements matching a query by bid: the highest-bidding advertiser got the top position, the second-highest the next, and so on. What can go wrong with this when the highest-bidding advertiser places an advertisement that is irrelevant to the query? Why might an advertiser with an irrelevant advertisement bid high in this manner?

Exercise 19.6

Suppose that, in addition to bids, we had for each advertiser their click-through rate: the ratio of the historical number of times users click on their advertisement to the number of times the advertisement was shown. Suggest a modification of the Goto scheme that exploits this data to avoid the problem in Exercise 19.5 above.

Online edition (c) 2009 Cambridge UP