MusculoSkeletal Exam

.pdf

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

Paradigm for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome

A 22-year-old man presents with a chief complaint of pain in the left occipital and temporal areas together with discomfort on the left posterolateral aspect of the neck. He describes having noticed a painful clicking associated with chewing. He reports having been involved in an altercation after a fraternity party 2 weeks ago. At that time, he was struck multiple times about the head and upper torso, being knocked to the ground and sustaining a laceration to the occipital region of his scalp, which required sutures. He had been found to be neurologically intact both in the emergency room and again on follow up examination. There has been no evidence found to indicate the presence of intracranial pathology.

His past medical history was noncontributory to his present complaints. Physical examination demonstrated the patient to be a well developed/well nourished young male in mild distress. He held his head slightly flexed and rotated towards the right. He spoke clearly, but had an asymmetry to his mandible on opening his mouth. There was no discomfort elicited on compression of the cervical spine. There was slight discomfort and limitation of head and neck extension and rotation to the left. Neurologically the patient was intact to the upper and lower extremities. The occipital scalp laceration was dry and healing per primum. There was palpable crepitus perceived over the left TMJ with movement of the jaw. There was also over tenderness on palpation over the left masseter muscle in the temporal region of the skull.

X-rays showed slight straightening and compensatory rotation of the cervical spine without fracture or dislocation of the bony elements. MRI of the jaw demonstrated damage to the fibrocartilaginous disc of the TMJ with surrounding soft tissue edema.

This is a paradigm for traumatic subluxation of the left TMJ and tear of surrounding ligamentous structures and intraarticular meniscus, and posttraumatic instability of the TMJ with secondary cervical muscular strain, because of:

A history of acute trauma

No prior history of symptoms Immediate onset of pain and dysfunction Asymmetry of mouth opening Limitation of cervical range of motion

tion may need to be modified if the patient reacts adversely with very little activity and requires a long time for relief.

The patient’s disorder may be related to age, gender, ethnic background, body type, static and dynamic posture, occupation, leisure activities, hobbies, and general activity level. Psychosocial issues, stress level, and coping mechanisms should be addressed. It is important to inquire about any change in daily routine and any unusual activities that the patient has participated in.

Gentle Palpation

The palpatory examination is started with the patient in the sitting position.

You should first search for areas of localized effusion, discoloration, birthmarks, open sinuses or drainage, incisional areas, bony contours and alignment, muscle girth and symmetry.

Remember to use the dominant eye when checking for alignment or symmetry. Failure to do this can alter the findings. You should not have to use deep pressure to determine areas of tenderness or malalignment. It is important to use firm but gentle pressure, which will enhance your palpatory skills. By having a sound basis of cross-sectional anatomy, you should not have to physically penetrate through several layers of tissue to have a good sense of the underlying structures. Remember, if the patient’s pain is increased at this point in the examination, the patient will be very reluctant to allow you to continue, or may become more limited in his or her ability to move.

Palpation is most easily performed with the patient in a relaxed position. Although the initial palpation may be performed with the patient sitting, the supine and prone positions allow for easier access to the bony and soft-tissue structures.

The easiest position for palpation of the posterior structures is with the patient supine and the examiner sitting behind the patient’s head. You can rest your forearms on the table, which enables you to relax your hands during palpation.

Posterior Aspect

Bony Structures

Mastoid Processes

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 41–42, Figure 4.8).

Transverse Processes of C1

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 42–43, Figure 4.9).

Soft-Tissue Structures

Trapezius

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 47–48, Figure 4.19).

Suboccipital Muscles

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 48–49, Figure 4.20).

85

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

Semispinalis Cervicis and Capitis

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 48, Figure 4.53).

Greater Occipital Nerves

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 48, Figure 4.20).

Ligamentum Nuchae

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 48–49, Figure 4.21).

Levator Scapulae

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 49) and Figure 8.71.

Anterior Aspect

To facilitate palpation of the anterior aspect of the neck, the patient should be in the supine position. The head should be supported and the neck relaxed. Make sure that the neck is in neutral alignment.

Bony Structures

Mandible

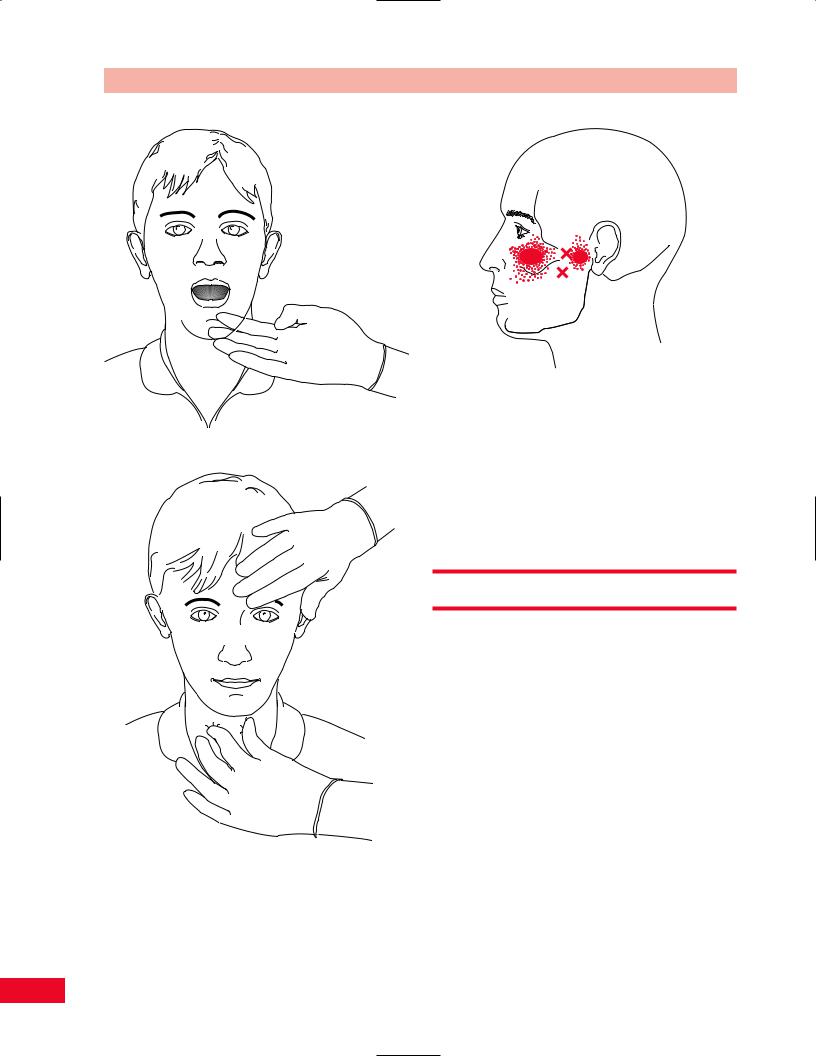

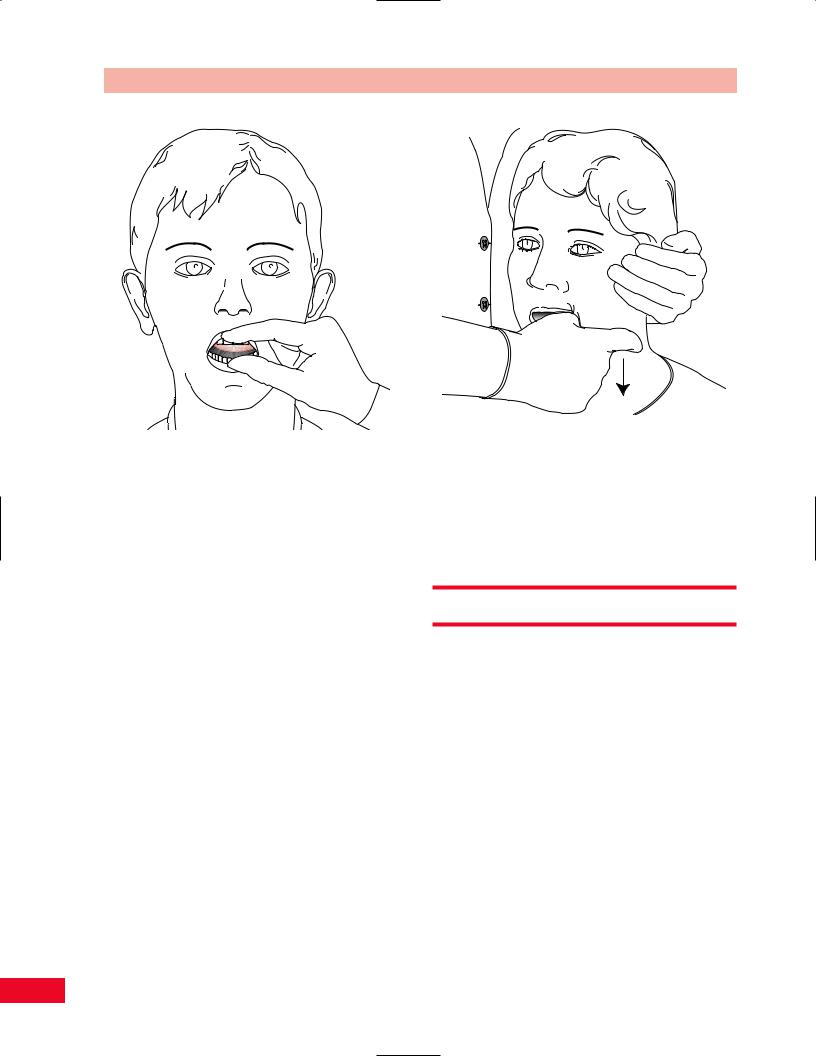

Run your fingers along the entire bony border of the mandible starting medial and inferior to the ears, move inferiorly to the angle of the mandible and then anteriorly and medially. Palpate both sides simultaneously (Figure 5.1).

Teeth

Wearing gloves, the examiner is able to retract the mouth and examine the teeth. Note if any teeth are missing or loose, the type of bite, and any malocclusion.

Hyoid

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 49, Figure 4.22).

Thyroid

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 51, Figure 4.23).

Cervical Spine

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 39–56) for a full description of palpation of all bony prominences and soft tissue structures.

Soft-Tissue Structures

Temporalis

Palpate on the lateral aspect of the skull over the temporal fossa. Ask the patient to close their mouth and you will be able to feel the muscle contract. Spasm of the muscle may be a cause of headaches (Figure 5.2).

Lateral and Medial Pterygoid

Place your gloved little or index finger between the cheek and the superior gum. Travel past the molar until

Temporalis

muscle

Mandible

Figure 5.1 Palpation of the mandible. |

Figure 5.2 Palpation of the temporalis muscle. |

86

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

A

Figure 5.3 Palpation of the pterygoid muscles.

you reach the neck of the mandible. Ask the patient to open their jaw and you will note tightness in the muscle. You will not be able to differentiate between the lateral and medial portions of the muscle (Iglarsh and SnyderMackler, 1994). Spasm in the muscle can cause pain in the ear and discomfort while eating (Figure 5.3).

Masseter

Place your gloved index finger in the patient’s mouth and slide the finger pad along the inside of the cheek approximately halfway between the zygomatic arch and the mandible. Simultaneously, palpate the external cheek with your index thumb. Ask the patient to close their mouth and you will feel the muscle contract (Figure 5.4).

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

Please refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 54–55, Figure 4.32).

Scaleni Muscles

Please refer to Chapter 4 (p. 55, Figure 4.32).

The Suprahyoid Muscle

Can be palpated externally inferior to the chin, in the arch of the mandible (Rocabado and Iglarsh, 1991). The infrahyoid muscle can be palpated on either side of the thyroid cartilage. A contraction of the muscle is felt if you gently resist cervical flexion at the beginning of the range (Rocabado and Iglarsh, 1991). Spasm in the suprahyoid muscle can elevate the hyoid and create

B

Figure 5.4 Palpation of the masseter muscle.

difficulty swallowing. Pain can also be felt in the mouth near the muscles’ origin (Figure 5.5).

Trigger Points of the TMJ Region

Myofascial pain of the TMJ region is quite common and can occur due to dental malocclusion, bruxism,

87

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

Figure 5.6 Trigger points of the lateral pterygoid, shown with common areas of referred pain.

A

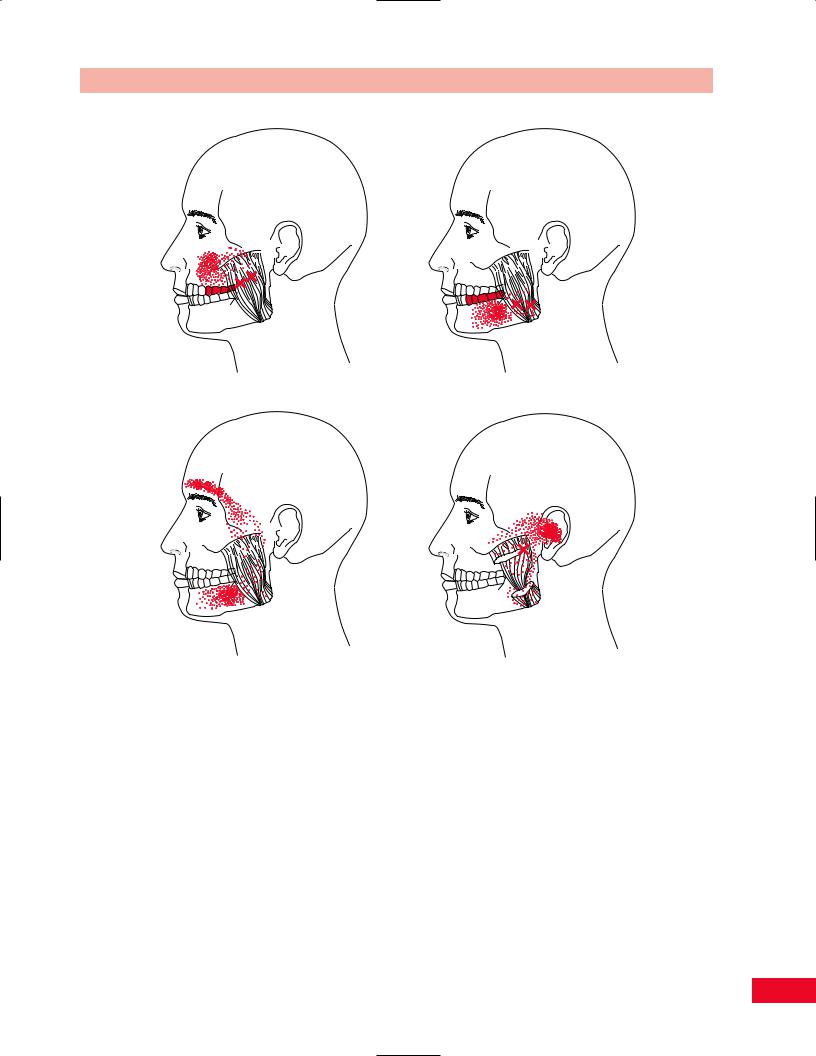

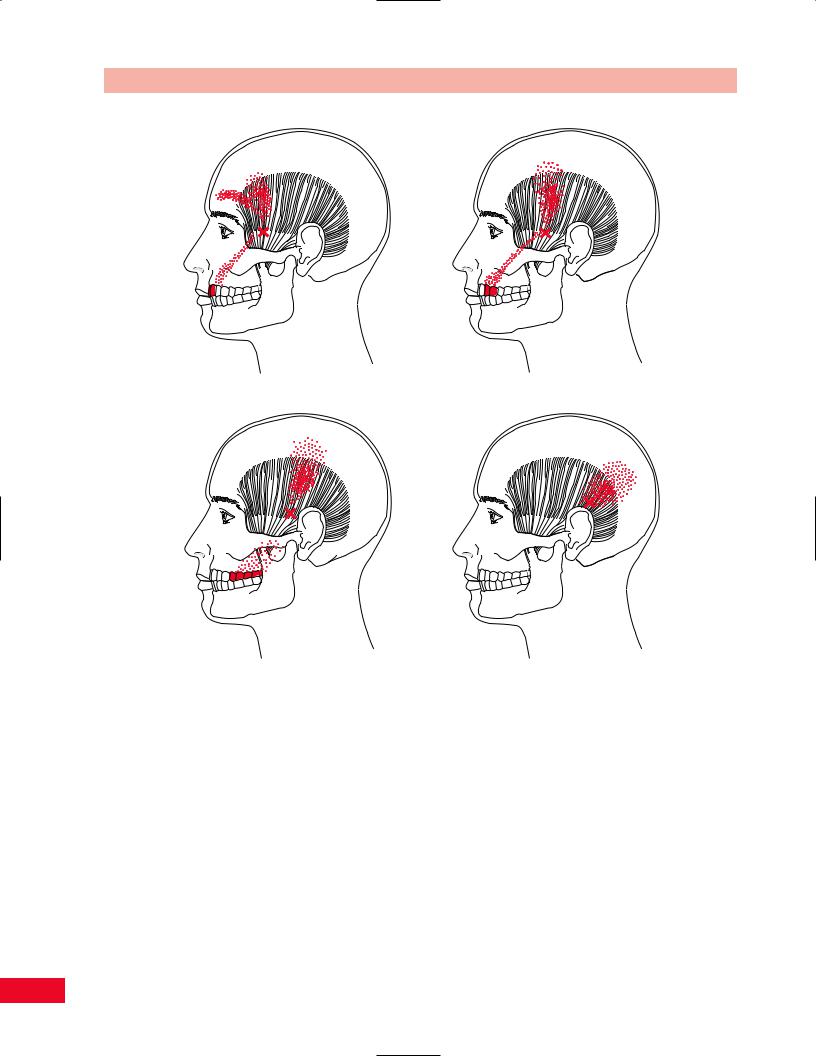

The masseter and lateral pterygoid are the most commonly affected, followed by the temporalis and medial pterygoid muscles. The location and referred pain zones for trigger points in these muscles are illustrated in Figures 5.6–5.9.

B

Figure 5.5 Palpation of the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles.

excessive gum chewing, prolonged mouth breathing (while wearing diving gear or a surgical mask), and trauma. Activation of these trigger points can cause headaches and can mimic TMJ intrinsic joint disease.

Active Movement Testing

Have the patient sit on a stool in a well-lit area of the examination room. Shadows from poor lighting will affect your perception of the movement. The patient should be appropriately disrobed so that you can observe the neck and upper thoracic spine. You should watch the patient’s movements from the anterior, posterior, and both lateral aspects. While observing the patient move, pay particular attention to his or her willingness to move, the quality of the motion, and the available range. Lines in the floor may serve as visual guides to the patient and alter the movement patterns. It may be helpful to ask the patient to repeat movements with the eyes closed. A full assessment of cervical movement should be performed first. (Refer to Chapter 4, pp. 57, 59–62 for a full description.) Note the position of the patient’s mouth with all the cervical movements.

Assess the active range of motion of the temporomandibular joints. Active movements of the temporomandibular joints include: opening of the mouth, closing of the mouth, protrusion, and lateral mandibular deviation to the right and left. While observing

88

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

A B

C D

Figure 5.7 Trigger points of the masseter, shown with common areas of referred pain.

the patient move, pay particular attention to his or her willingness to move, the quality of the motion, the available range, and any deviations that might be present.

Movement can be detected by placing your fourth or fifth fingers in the patient’s ears to palpate the condyles. The TM joints can also be palpated externally, by placing your index finger anterior to the ear. Note any clicking, popping, or grinding with the movement. Pain or tenderness, especially on closing, is indicative of posterior capsulitis (Magee, 1997). During opening of the jaw, the condyle must move forward. Full opening requires that the condyles rotate and translate equally (Magee, 1997) If this symmetrical movement does not occur, you will note a deviation. Loss of motion can be secondary to rheumatoid

arthritis, congenital bone abnormalities, soft tissue or bony ankylosis, osteoarthritis, and muscle spasm (Hoppenfeld, 1976).

The TMJ is intimately related to both the cervical spine and the mouth. To be complete in the evaluative process, cervical active range of motion should be included in the examination of the TMJ. Details of cervical spine testing can be found in Chapter 4 (pp. 57, 59–61, Figure 4.43).

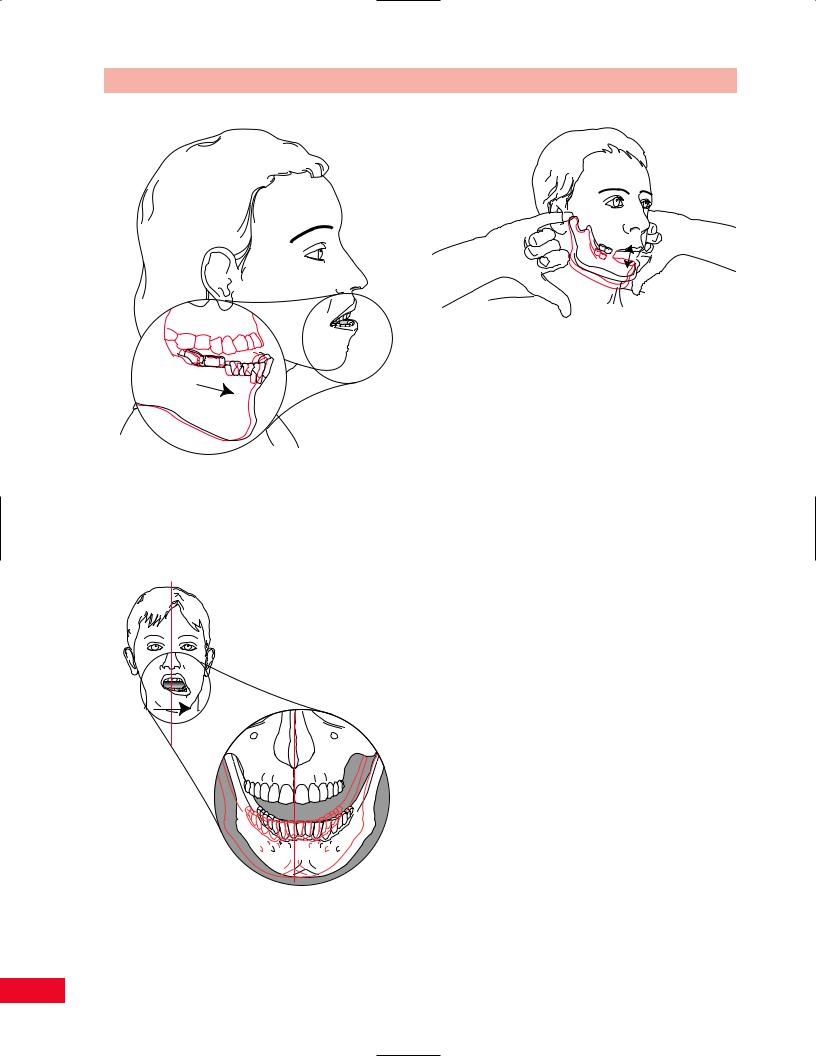

Opening of the Mouth

Ask the patient to open their mouth as far as they can. Both TM joints should be working simultaneously and synchronously, allowing the mandible to open

89

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

A B

C D

Figure 5.8 Trigger points of the temporalis, shown with common areas of referred pain.

evenly without deviation to one side. The clinician should palpate the opening by placing their fifth fingers into the patient’s external auditory meatus with the

finger pads facing anteriorly and should feel the condyles move away from their fingers. If one TM joint is hypomobile, then the jaw will deviate to that side. Normal range of motion of opening is between 35 and 55 mm from the rest position to full opening (Magee, 1997). The opening should be measured between the maxillary and mandibular incisors. If the jaw opens less than 25–33 mm it is classified as being hypomobile. If opening is greater than 50 mm then the joint is classified as hypermobile (Iglarsh and SnyderMackler, 1994). A quick functional test is performed by asking the patient to place 2–3 flexed fingers, at

their knuckles, between the upper and lower teeth (Figure 5.10).

Closing of the Mouth

The patient is instructed to close their mouth from full opening. The clinician should palpate the opening by placing their fifth fingers into the patient’s external auditory meatus with the finger pads facing anteriorly and should feel the condyles move toward their fingers.

Protrusion of the Mandible

The patient should be instructed to jut the jaw anteriorly so that it protrudes out from the upper teeth.

90

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

A

Medial pterygoid muscle

B

Figure 5.9 Trigger points of the medial pterygoid, shown with common areas of referred pain.

The movement should not be difficult for the patient to perform. Measure the distance the lower teeth protrude anteriorly past the upper teeth. Normal range of motion for this movement should be between 3 and 6 mm from the resting position to the protruded position (Magee, 1997; Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994) (Figure 5.11).

Lateral Mandibular Deviation

The patient should be instructed to disengage his or her bite and then move the mandible first to one side, back to the midline, and then to the other side. The clinician should pick points on both the upper and lower teeth to be used as markers for measuring the amount of lateral deviation. The normal amount of lateral deviation is 10–15 mm (Magee, 1997) approx-

A

B

Figure 5.10 Observe as the patient opens their mouth as far as they can. Both TM joints should be working simultaneously and synchronously allowing the mandible to open evenly without deviation to one side. A quick functional test is performed by asking the patient to place 2–3 flexed fingers, at their knuckles, between the upper and lower teeth.

imately one-fourth of the range of opening (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994). Lateral deviation to one side from the normal resting position or an abnormal degree of deviation may be caused by muscle dysfunction of the masseter, temporalis, or lateral pterygoid, or problems with the disc or lateral ligament on the opposite side from which the jaw deviates (Magee, 1997) (Figure 5.12).

Measurements of temporomandibular joint movements can be made by using a ruler marked in millimeters, or a Boley gauge (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994).

91

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

Figure 5.11 Observe as the patient juts the jaw anteriorly so that it protrudes out from the upper teeth.

Figure 5.12 Observe as the patient disengages his or her bite and then moves the mandible first to one side, back to the midline, and then to the other side.

Figure 5.13 The freeway space is the point within the open pack position where the soft tissues of the temporomandibular joints are the most relaxed.

Assessing the Freeway Space

The freeway space is the point within the open pack position where the soft tissues of the temporomandibular joints are the most relaxed. The patient can achieve this position by leaving their tongue on their hard palate and leaving the mandible slightly depressed. You can assess the freeway position by placing your fourth fingers, pad facing anteriorly into the patient’s external auditory meatus as the patient slowly closes their mouth. The freeway space is achieved when you palpate the mandibular heads touching your finger pads (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994). The normal measurement is 2–4 mm (Harrison, 1997) (Figure 5.13).

Measurement of Overbite

Ask the patient to close their mouth. Mark the point where the maxillary teeth overlap the mandibular teeth. Ask the patient to open their mouth and measure from the top of the teeth to the line that you marked. This measurement is usually 2–3 mm (Iglarsh and SnyderMackler, 1994; Rocabado, unpublished data, 1982) (Figure 5.14).

Measurement of Overjet

Overjet is the distance that the maxillary teeth protrude anteriorly over the mandibular teeth. Ask the patient to close their mouth and measure from underneath the maxillary incisors to the anterior surface of the mandibular incisors. This measurement is usually

92

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

Overbite

A

B

Overjet

Figure 5.14 Overbite is the point where the maxillary teeth overlap the mandibular teeth. Overjet is the distance that the maxillary teeth protrude anteriorly over the mandibular teeth.

2–3 mm (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994; Rocabado, unpublished data, 1982) (Figure 5.14).

Figure 5.15 Measurement of the mandible is taken from the back of the TMJ to the notch of the chin. Compare the measurement of both sides.

Mandibular Measurement

Measure from the back of the TMJ to the notch of the chin. Compare both sides. If one side is asymmetrical from the other a structural or developmental deformity may be present. Normal measurements should be between 10 and 12 cm (Magee, 1997) (Figure 5.15).

Swallowing and Tongue Position

The patient is instructed to swallow with their tongue in the normal relaxed position. The gloved clinician separates the patient’s lips and observes the position of the tongue. The normal position should be at the top of the palate (Figure 5.16).

Passive Movement Testing

Passive movement testing can be divided into two categories: physiological movements (cardinal plane), which are the same as the active movements, and mobility testing of the accessory (joint play, component) movements. Using these tests helps to differentiate the contractile from the noncontractile (inert) elements. These elements (ligaments, joint capsule, fascia, bursa, dura mater, and nerve root) (Cyriax, 1979) are stretched or stressed when the joint is taken to the end of the available range. At the end of each passive physiological movement you should sense the end feel and determine whether it is normal or pathological.

93

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

Figure 5.16 The normal position of the tongue is at the top of the palate.

Passive Physiological Movements

Passive testing of the physiological movements are easiest if they are performed with the patient in the sitting position. Testing of the cervical spine movements is described in Chapter 4 on the Cervical Spine (pp. 62–65). Passive movement testing of the TM joint is rarely performed unless the clinician is examining the end feel of the movement. The end feel of opening is firm and ligamentous while the end feel of closing is hard, teeth to teeth.

Mobility Testing of Accessory Movements

Mobility testing of accessory movements will give you information about the degree of laxity or hypomobility present in the joint and the end feel. The patient must be totally relaxed and comfortable to allow you to move the joint and obtain the most accurate information.

Distraction of the

Temporomandibular Joint

The patient is in the sitting position with the examiner to one side of the patient. The clinician places their gloved thumb into the patient’s mouth on the superior aspect of the patient’s molars and pushes inferiorly. The examiner’s index finger simultaneously rests on the exterior surface of the mandible and pulls inferiorly

Figure 5.17 Mobility testing of distraction of the temporomandibular joint.

and anteriorly. The test should be performed unilaterally with one hand testing mobility and the other hand available to stabilize the head. The end feel should be firm and abrupt (Figure 5.17).

Resistive Testing

Movements of the jaw are complex due to the freedom of movement allowed by the TM joints. The cervical muscles serve to stabilize the head as the muscles of mastication act on the mandible. The temporalis and masseter are the main closing muscles. The inferior portion of the lateral pterygoid functions to open the mouth and protrude the mandible. The superior portion of the lateral pterygoid stabilizes the mandibular condylar process and disc during closure of the mouth. Extreme weakness of these muscles is unusual except in cases of central nervous system or trigeminal nerve damage.

Jaw Opening

The primary mouth opener is the lateral pterygoid (inferior portion) (Figure 5.18). The anterior head of the digastric muscle assists this muscle.

•Position of patient: Sitting, facing you.

•Resisted test: Place the palm of your hand under the patient’s chin and ask them to open their

94