MusculoSkeletal Exam

.pdf

Chapter 4 The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine

C7

Motor

Elbow extension (triceps brachii)

Resistance

Movement

C7

Sensation

C5

T2

T1 |

C6 |

Key C7 |

|

sensory area |

|||

|

|

||

Anterior view |

C8 |

C7 |

|

|

Reflex

Triceps reflex

Figure 4.63 The C7 root level.

75

The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine Chapter 4

C8

Motor

Finger flexion (flexor digitorum profundis)

Movement

C7

T1

Sensation

C5

T2

T1 |

C6 |

|

|

C8 |

C7 |

Anterior view

Key C8 sensory area

Reflex "No Reflex"

Figure 4.64 The C8 root level.

76

Chapter 4 The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine

T1

Finger abduction (abductor digiti quinti, first dorsal interosseous)

Motor

A B

C D

Movement

Resistance

A  B

B

T1

C D

Sensation

C5

T2 |

|

|

T1 |

C6 |

|

Key T1 |

C8 |

C7 |

sensory area |

|

|

Anterior view

Reflex "No Reflex"

Figure 4.65 The T1 root level.

77

The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine Chapter 4

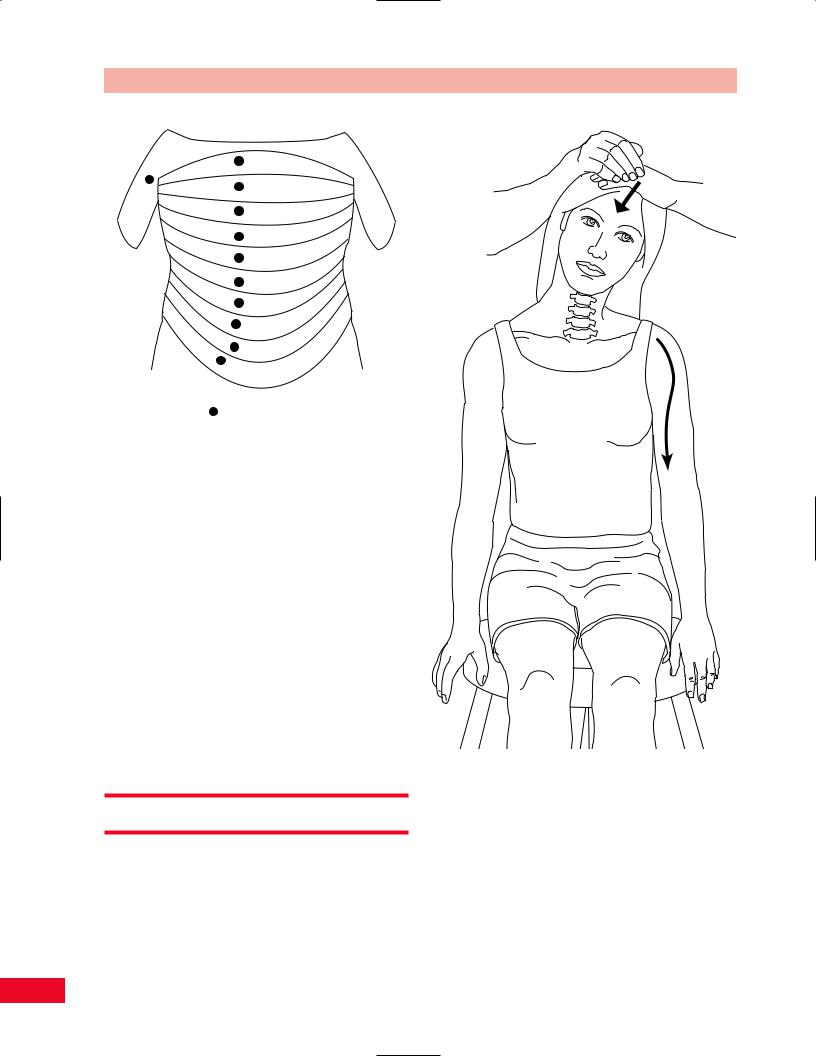

T2

T3

T4

T5

T6

T7

T8

T9

T10

T11

T12

Key sensory areas

Figure 4.66 The thoracic dermatomes and their key sensory areas.

Sensation

The key sensory area for T1 is located on the medial aspect of the arm just proximal to the antecubital fossa.

Reflex

None.

T2 through T12 Root Levels

The thoracic root levels are tested primarily by sensation, and the key sensory areas are located just to the side of the midline on the trunk as illustrated in Figure 4.66. The only exception to this is the T2 key sensory area, which is located in the anteromedial aspect of the distal axilla.

Special Tests

Compression of the cervical spine from above is performed to reproduce or amplify the radicular symptoms of pain or parasthesias that occur due to compression of the cervical nerve roots in the neural foramina. The neural foramina become narrowed when the patient extends the neck, rotates the neck, or laterally bends the head toward the side to be tested.

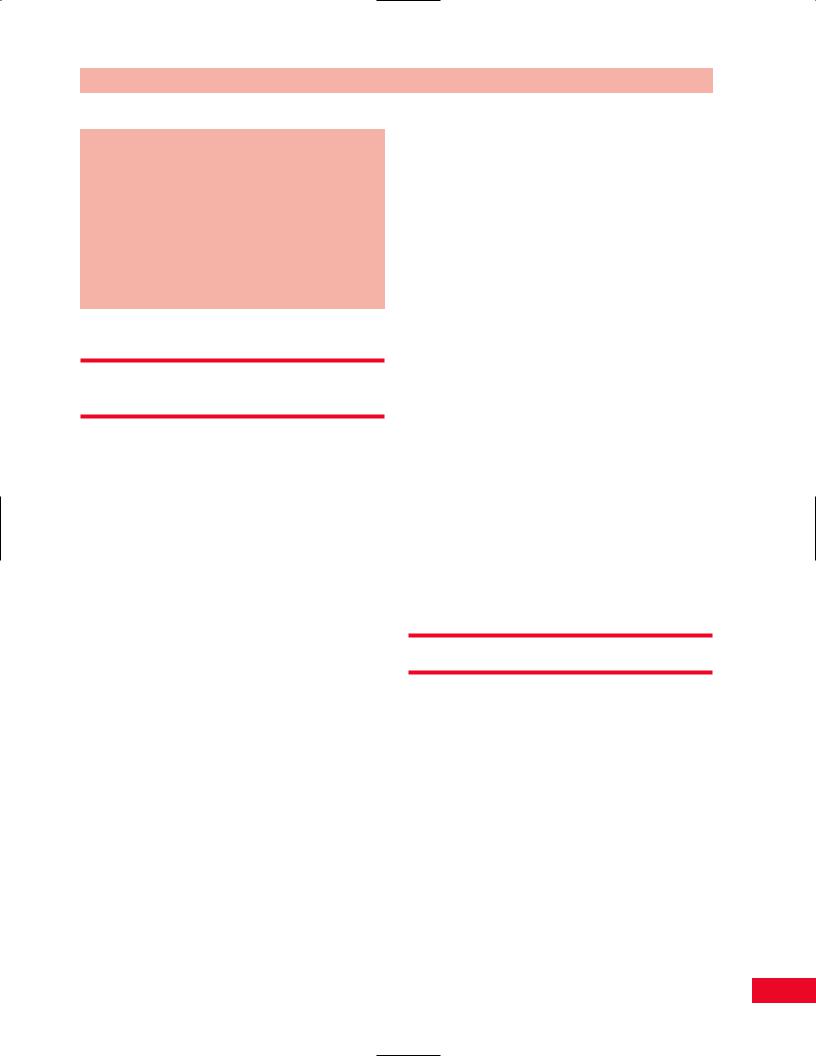

Figure 4.67 The Spurling test. The patient’s head is flexed laterally. Compression causes the neural foramina on the same side to narrow in diameter.

Spurling Test

The Spurling test (Figure 4.67) is performed with the patient’s neck in lateral flexion. The patient is sitting. Place your hand on top of the patient’s head and press down firmly or bang the back of your hand with your fist. If the patient complains of an increase in radicular symptoms in the extremity, the test finding

78

Figure 4.68 The distraction test. Distracting the cervical spine increases the diameter of the neural foramina.

is positive. The distribution of the pain and abnormal sensation is useful in determining which root level may be involved.

Distraction Test

The distraction test (Figure 4.68) is performed in an effort to reduce the patient’s symptoms by opening the neural foramina. The patient is sitting. Place one of your hands under the patient’s chin and the other hand around the back of the head. Lift the patient’s head slowly to distract the cervical spine. If the patient notes relief or diminished pain, then the test finding is positive for nerve root damage. Be careful to protect the temporomandibular joint when pulling up on the chin.

Lhermitte’s Sign

Lhermitte’s sign (Figure 4.69) is used to diagnose meningeal irritation and may also be seen in multiple sclerosis. The patient is sitting. Passively flex the patient’s head forward so that the chin approaches the chest. If the patient complains of pain or parasthesias down the spine, the test result is positive. The patient may also complain of radiating pain into the upper or lower extremities. Flexion of the hips can also be performed simultaneously with head flexion (i.e., with the patient in the long sitting position).

Chapter 4 The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine

Figure 4.69 Lhermitte’s sign.

Vertebral Artery Test

Movement of the cervical spine affects the vertebral arteries because they course through the foramina of the cervical vertebrae. These foramina may be stenotic and extension of the cervical spine may cause symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, or nystagmus. The vertebral artery test is performed prior to manipulation of the cervical spine, to test the patency of the vertebral arteries. The patient is most easily tested in a supine position. Place the patient’s head and neck in the following positions passively for at least 30 seconds, and observe for symptoms or signs as previously described: head and neck extension; head and neck rotation to the right and left; head and neck rotation to the right and left with the neck in extension (with or without lateral bending to the opposite side). Take time between each position to allow the patient to re-equilibrate. In general, turning the head to the right will affect the left vertebral artery more so and vice versa (Figure 4.70).

Referred Pain Patterns

Pain in the cervical spine may result from disease or infection in the throat, ears, face, scalp, jaw, or teeth (Figure 4.71).

79

Figure 4.72 Anteroposterior view of the cervical spine.

Figure 4.70 Vertebral artery test. This test should be performed if cervical manipulation is being contemplated.

Scalp Ears

Face

Jaw and

Teeth

Throat

Figure 4.71 The scalp, ears, face, jaw, teeth, and throat may all refer pain to the cervical spine.

Figure 4.73 Lateral view of the cervical spine.

80

Chapter 4 The Cervical Spine and Thoracic Spine

Radiological Views

Radiological views of the cervical spine are provided in Figures 4.72–4.75.

V = Vertebral body

D = Intervertebral disc Sc = Spinal cord

S= Spinous process

N= Neural foramen

P= Pedicle of vertebral arch

I= Intervertebral disc space

F= Facet joints

T= T1 Transverse process

Figure 4.75 Magnetic resonance image of the cervical spine, sagittal view.

Figure 4.74 Oblique view of the cervical spine.

81

Chapter 5

The

Temporomandibular

Joint

Temporal |

|

squama |

Greater wing |

|

of sphenoid |

Te

joinnt

joinnt

Zygoma

Maxilla

Mastoi d

Mastoi d

roces

roces

H ead (ccondyle) of manddible

Ramuus of mandible

Please refer to Chapter 2 for an overview of the sequence of a physical examination. For purposes of length and to avoid having to repeat anatomy more than once, the palpation section appears directly after the section on subjective examination and before any section on testing, rather than at the end of each chapter. The order in which the examination is performed should be based on your experience and personal preference as well as the presentation of the patient.

Functional Anatomy of the

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The TMJ is a synovial articulation. It is formed by the domed head of the mandible resting in the shallow mandibular fossa at the inferolateral aspect of the skull beneath the middle cranial fossa. Similar to the acromioclavicular joint of the shoulder, the articular surfaces of the TMJ are separated by a fibrous articular disc. The surface area of the mandibular head is similar in size to that of the tip of the small finger, yet it is subjected to many hundreds of pounds of compressive load with each bite of an apple or chew of a piece of meat.

Downward movement of the jaw is accomplished by a combination of gravity and muscular effort. The masseter and temporalis muscles perform closing of the mouth. The temporalis muscle inserts on the coronoid process. As such it functions very much like the flexors of the elbow. The masseter is attached to the lateral surface of the mandible along its posterior inferior angle. The mandible is stabilized against the infratemporal surface of the skull by contraction of the pterygoid muscles. The lateral pterygoid is attached directly onto the medial aspect of the articular disc.

There are numerous neurological structures about the TMJ. Branches of the auricular-temporal nerve provide sensation to the region. The last four cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, and XII) lie deep and in close proximity to the medial surface of the TMJ.

Given the great magnitude of repetitive forces traversing the relatively small articular surfaces of the TMJ, it is remarkable that it normally functions as well as it does over many years of use. It is equally understandable why when the anatomy of the TMJ has been altered this articulation may become an extremely painful and challenging problem.

Chapter 5 The Temporomandibular Joint

Trauma to the face and jaw may cause subluxation or dislocation of the TMJ. Untreated compromise of ligamentous stability will result, just as in the knee, in the rapid development of premature degenerative arthritis of the joint.

Instability of the TMJ may also be the result of exuberant synovitis secondary to inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, stretching capsular ligaments. The resultant instability causes further inflammation, swelling, pain and compromise of joint function.

Damage to the articular disc either by direct trauma, inflammation or simple senescence exposes the articular surfaces of the TMJ to excessive loads. This is yet another pathway leading to the premature and rapid onset of a painful osteoarthritic joint.

Given the density of neurological structures in close proximity to the TMJ, pain referred from the TMJ may be perceived about the face, scalp, neck, and shoulder. Complaints in these areas resulting from TMJ pathology are often difficult to analyze. This situation often leads to incomplete or inaccurate diagnoses and inappropriate treatment plans. As with other pathological articular conditions, a greater likelihood of success with treatment requires a thorough knowledge of local anatomy together with an accurate history and a meticulous physical examination of the patient.

The TMJ is a synovial joint, lined with fibrocartilage and divided in half by an articular disc. The TMJs must be examined together along with the teeth.

Observation

Note the manner in which the patient is sitting in the waiting room. Notice how the patient is posturing the head, neck, and upper extremities. Refer to Chapter 4 (pp. 37–38) for additional questions relating to the cervical spine. Is there facial symmetry? Is the jaw in the normal resting position (mouth slightly open but lips in contact)? How is the chin lined up with the nose in the resting position and in full opening? (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994) Is the patient supporting his or her jaw? Are they having difficulty talking and opening their mouth? Are the teeth in contact or slightly apart? Is there a crossbite, underbite, overbite or malocclusion? Patients with a crossbite present with their mandibular teeth laterally displaced to their maxillary teeth. Patients with an underbite present with their mandibular teeth anteriorly displaced to their maxillary teeth. Patients with an overbite present with

83

The Temporomandibular Joint Chapter 5

their maxillary teeth extending below the mandibular teeth. Is hypertrophy of the masseters present? Is there normal movement of the tongue? The patient should be able to move the tongue up to the palate, protrude and click it. Observe the tongue. Is there scalloping on the edges or does the patient bite the tongue? This may indicate that the tongue is too wide or rests between the teeth (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994).

What is the resting position of the tongue and where is it when the patient swallows? The normal resting position of the tongue should be on the hard palate. Are all the patient’s teeth intact? Do you notice any swelling or bleeding around gums?

Observe the patient as he or she assumes the standing position and note their posture. Pay particular attention to the position of the head, cervical and thoracic spine. Additional information relating to posture of the spine can be found in Chapters 2 and 4 (pp. 18–29 and pp. 37–38). Pain may be altered by changes in position so watch the patient’s facial expression for indications as to their pain level.

Subjective Examination

The temporomandibular joints (TM joints) are extremely well utilized and are opened approximately 1800 times during the day (Harrison, 1997). These joints are essential in our ability to eat, yawn, brush our teeth, and talk. They are intimately related to the head and cervical spine and should be included in their examination. Approximately 12.1% of Americans experience head and neck pain (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994). Unfortunately, however, these problems are frequently overlooked in the examination process.

You should inquire about the nature and location of the patient’s complaints and their duration and intensity. Note if the pain travels up to the patient’s head or distally to below the elbow. The behavior of the pain during the day and night should also be addressed. Is the patient able to sleep or is he or she awakened during the night? What position does the patient sleep in? How many pillows do they use? What type of pillow is used? Additional subjective questions relating to the cervical spine can be found in Chapter 4 (pp. 38–39) and in Box 2.1 (p. 18) for typical questions of subjective examination.

Does the patient report trauma to the TMJ joints? Was the patient hit in the jaw or did he or she fall on their face? Did he or she bite down on something

hard? Was the mouth held open excessively for a prolonged period of time (at the dentist’s office)? Did the patient overuse the joint by talking for a prolonged period of time or chewing on a tough piece of meat? Was traction applied to the neck, compressing the jaw with part of the harness?

Does the patient experience pain on opening or closing of the mouth? Pain in the fully opened position may be from an extra-articular problem, while pain with biting may be an intra-articular problem (Magee, 1997). Does the patient complain of clicking with movement. Crepitus may be indicative of DJD. Has the patient ever experienced locking of the jaw? This may be due to displacement of the disc. If the jaw locks in the open position, the TMJ might have dislocated (Magee, 1997). Is there limited opening of the mouth? Does the patient have pain with yawning, swallowing, speaking, shouting? Is there pain while eating? Does the patient chew equally on both sides of their mouth? Has the patient had previous dental interventions? Teeth may have been pulled or ground down. Does the patient clench or grind (bruxism) his or her teeth? If the front teeth are in contact and the back teeth are not, there is a malocclusion. Has the patient worn braces? When and for how long? The braces will have altered the occlusion. Has the patient been wearing a dental appliance? What type of appliance are they using and how long have they been wearing it? Has the appliance been helpful in alleviating the patient’s symptoms?

Special Questions

Was the patient breast or bottle-fed? (Iglarsh and Snyder-Mackler, 1994) Did the patient suck on a pacifier or on their fingers and for how long? Is the patient a mouth breather? This alters the position of the tongue on the palate. Does the patient complain of problems swallowing? This may be due to cranial nerve problems of the CN VII (facial nerve) and CN V (trigeminal nerve). Earaches, dizziness, or headaches may be due to TMJ, inner ear or upper cervical spine problems.

Consider the factors that make the patient’s complaints increase or ease. He or she may present with the following complaints: headaches, dizziness, seizures, nausea, blurred vision, nystagmus, or stuffiness. How easily is the patient’s condition irritated and how quickly can the symptoms be relieved? The examina-

84