- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •1 Introduction to Anatomic Systems and Terminology

- •2 Clinical Imaging Basics Introduction

- •3 Back

- •4 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Spine

- •5 Overview of the Thorax

- •6 Thoracic Wall

- •7 Mediastinum

- •8 Pulmonary Cavities

- •9 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Thorax

- •10 The Abdominal Wall and Inguinal Region

- •12 Abdominal Viscera

- •13 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Abdomen

- •14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

- •15 Pelvic Viscera

- •16 The Perineum

- •18 Overview of the Upper Limb

- •19 Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb

- •20 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Upper Limb

- •21 Overview of the Lower Limb

- •22 Functional Anatomy of the Lower Limb

- •23 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Lower Limb

- •24 Overview of the Head and Neck

- •25 The Neck

- •26 Meninges, Brain, and Cranial Nerves

- •29 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Head and Neck

- •Index

25 The Neck

The neck extends from the base of the skull to the clavicles and manubrium. It contains vital neurovascular structures that supply the head, the thorax, and the upper limb. The neck also contains musculoskeletal elements that support and move the head and viscera of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and endocrine systems.

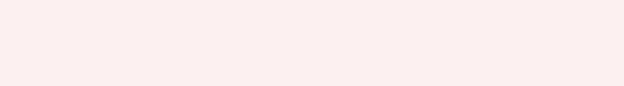

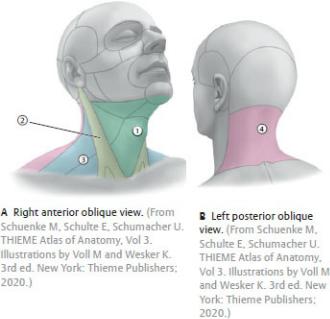

25.1 Regions of the Neck

The regions of the neck, defined by muscular and skeletal boundaries, are largely descriptive rather than functional, but they are useful for understanding the topographic relationships in the neck, which often play a significant role in medical practice (Table 25.1; Figs. 25.1). Refer to Section 25.8 for detailed anatomic relations of these regions.

—The anterior cervical region (anterior triangle) extends from the midline of the neck to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

•The region is further divided into submandibular, submental, muscular, and carotid triangles.

•The anterior region contains most of the cervical viscera, which includes the lower pharynx, esophagus, larynx, trachea, thyroid, and parathyroid glands.

—The sternocleidomastoid region is a narrow area defined by the anterior and posterior borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

•Inferiorly, the sternal and clavicular heads of the muscle define the small lesser supraclavicular fossa.

•This region contains parts of the major vascular structures of the neck.

—The lateral cervical region (posterior triangle) extends from the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the anterior border of the trapezius muscle.

•The posterior belly of the omohyoid muscle divides this region into omoclavicular and occipital triangles.

•The scalene muscles and cervical and brachial plexuses are located in

this region.

—The posterior cervical region extends from the anterior border of the trapezius muscle to the posterior midline of the neck.

•It contains the trapezius and suboccipital muscles, the vertebral artery, and posterior branches of the cervical plexus.

—The root of neck, a transition area for structures passing between the thorax and neck, is enclosed by the superior thoracic aperture, which is formed by the manubrium, the first ribs and their costal cartilages, and the first thoracic vertebra.

•It contains the trachea, esophagus, common carotid and subclavian arteries, brachiocephalic veins, vagus and phrenic nerves, the sympathetic trunk, the thoracic duct, and the apex of each lung.

Table 25.1 Regions of the Neck |

|

|

|

|

|

Region |

Divisions |

Contents |

Anterior cervical |

Submandibular |

Submandibular gland and |

region (triangle) |

(digastric) triangle |

lymph nodes, hypoglossal |

|

|

n. (CN XII), facial a. and v. |

|

|

|

|

Submental triangle |

Submental lymph nodes |

|

|

|

|

Muscular triangle |

Sternothyroid and |

|

|

sternohyoid muscles, |

|

|

thyroid and parathyroid |

|

|

glands |

|

|

|

|

Carotid triangle |

Carotid bifurcation, carotid |

|

|

body, hypoglossal (CN XII) |

|

|

and vagus (CN X) nn. |

|

|

|

Sternocleidomastoid region* |

Sternocleidomastoid, |

|

|

|

common carotid a., internal |

|

|

jugular v., vagus n. (CN X), |

|

|

jugular lymph nodes |

|

|

|

Lateral cervical |

Omoclavicular |

Subclavian a., subscapular |

region (posterior |

(subclavian) triangle |

a., supraclavicular I.n. |

triangle) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occipital triangle |

Accessory n. (CN XI), |

|

|

trunks of brachial plexus, |

|

|

transverse cervical a., |

|

|

cervical plexus (posterior |

|

|

branches) |

|

|

|

Posterior cervical region |

Nuchal muscles, vertebral |

|

|

|

a., cervical plexus |

|

|

|

* The sternocleidomastoid region also contains the lesser supraclavicular fossa.

Fig. 25.1 Cervical regions

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

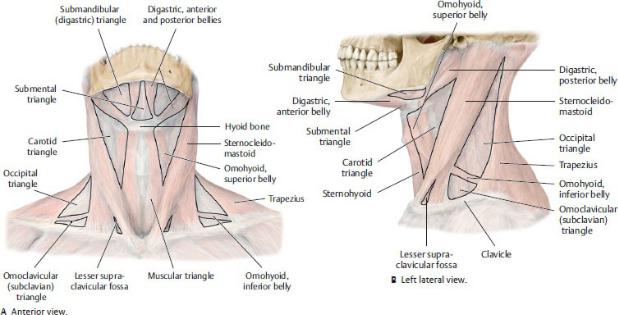

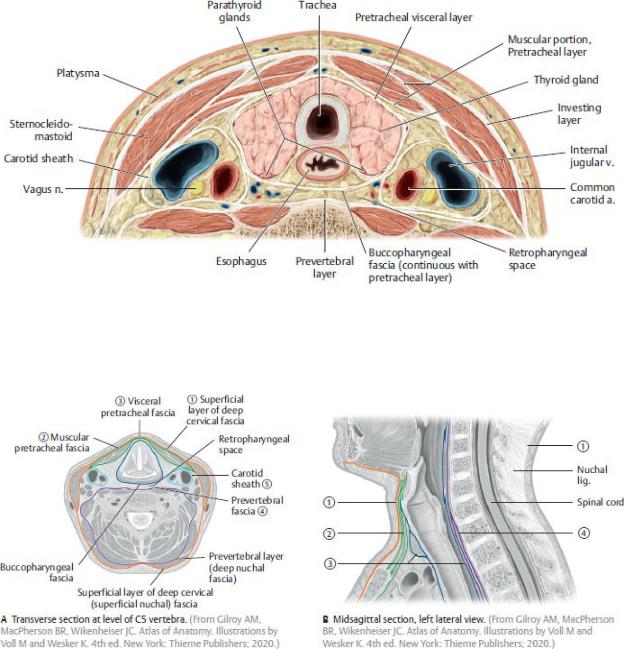

25.2 Deep Fascia of the Neck

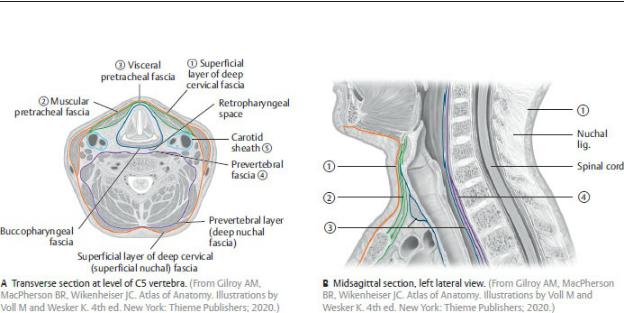

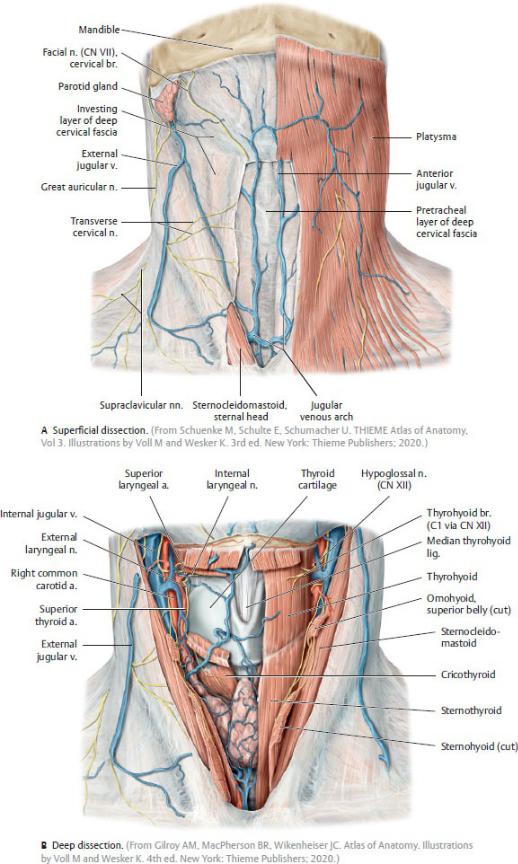

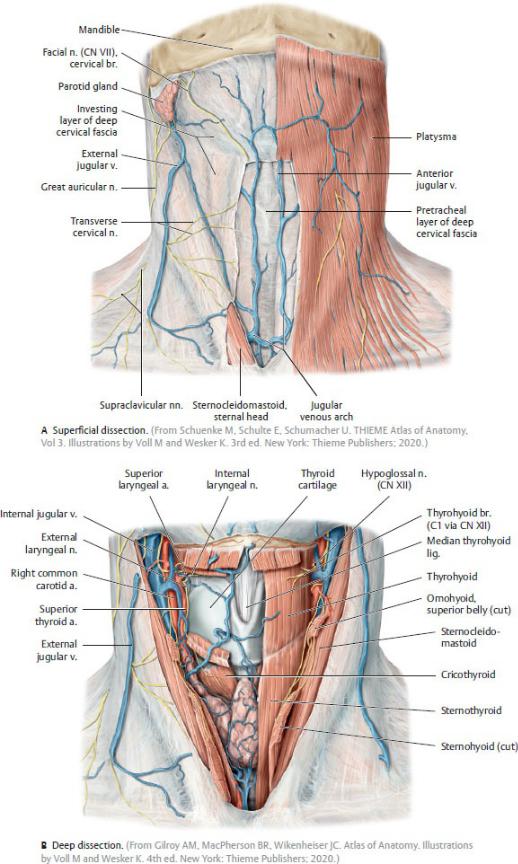

The deep cervical fascia is divided into four layers that surround and compartmentalize the structures of the neck (Fig. 25.2; Table 25.2).

—The investing (superficial) layer of the deep fascia of the neck, a thin layer that lies deep to the skin, surrounds the entire neck but splits to enclose the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles and contains cutaneous nerves, superficial vessels, and superficial lymphatics of the neck.

—The pretracheal fascia in the anterior neck has a muscular lamina (layer) that encloses the infrahyoid muscles and a visceral lamina that encloses the viscera of the anterior neck.

—The prevertebral fascia surrounds the vertebral column and the deep neck muscles and is continuous with the nuchal fascia posteriorly.

—The carotid sheath, a condensation of the pretracheal, prevertebral, and investing fasciae, forms a narrow cylindrical tube that encloses the neurovascular bundle of the neck: the internal jugular vein, common carotid artery, and vagus nerve.

—The retropharyngeal space, a potential space between the visceral layer of the pretracheal fascia and the prevertebral fascia, extends from the base of the skull superiorly to the superior mediastinum inferiorly.

Fig. 25.2 Fascial layers in the anterior neck

Transverse section of the neck at the level of C6, superior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Table 25.2 Deep Cervical Fascia

The deep cervical fascia is divided into four layers that enclose the structures of the neck.

Layer |

Type of |

Description |

|

Fascia |

|

○ Investing |

Muscular |

Envelopes entire neck; splits to |

(superficial) layer |

|

enclose sternocleidomastoid and |

|

|

trapezius muscles |

Pretracheal layer |

○ |

Encloses infrahyoid muscles |

|

Muscular |

|

|

|

|

|

○ Visceral |

Surrounds thyroid gland, larynx, |

|

|

trachea, pharynx, and esophagus |

|

|

|

○ Prevertebral |

Muscular |

Surrounds cervical vertebral |

layer |

|

column and associated muscles |

|

|

|

○ Carotid sheath |

Neurovascular |

Encloses common carotid artery, |

|

|

internal jugular vein, and vagus |

|

|

nerve |

|

|

|

25.3 Muscles of the Neck

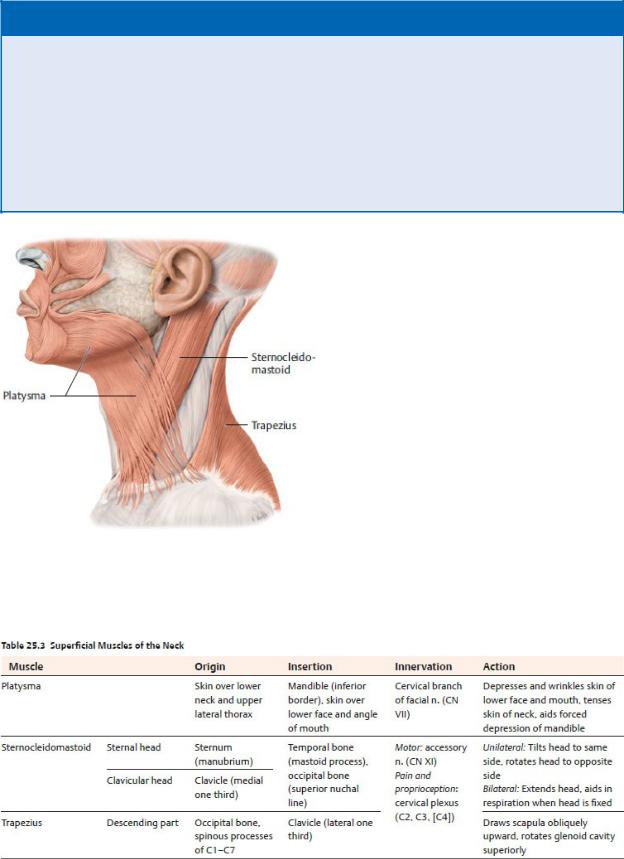

—Three muscles form the most superficial muscular layer of the neck (Fig. 25.3; Table 25.3):

•The platysma, enclosed within the superficial fascia of the neck, is a muscle of facial expression, and therefore a subcutaneous muscle, that extends onto the anterolateral surfaces of the neck.

•The sternocleidomastoid muscle, enclosed within the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia, is a visible landmark that divides the neck into anterior and lateral cervical regions.

•The trapezius, also within the investing fascial layer, is a muscle of the shoulder girdle that extends onto the neck and forms the posterior border of the lateral cervical region.

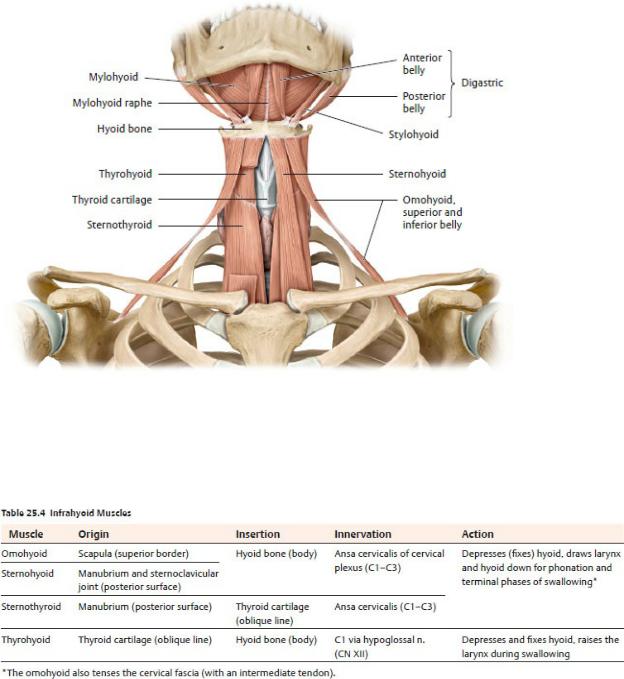

—Muscles attached to the hyoid bone lie between the superficial and deep neck muscles.

•Suprahyoid muscles, the digastric, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and hyoglossus, form the floor of the mouth and elevate the hyoid and larynx during swallowing and phonation (see Table 27.9).

•Infrahyoid muscles in the neck, omohyoid, sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and thyrohyoid, depress the hyoid and larynx during swallowing and phonation (Fig. 25.4; Table 25.4).

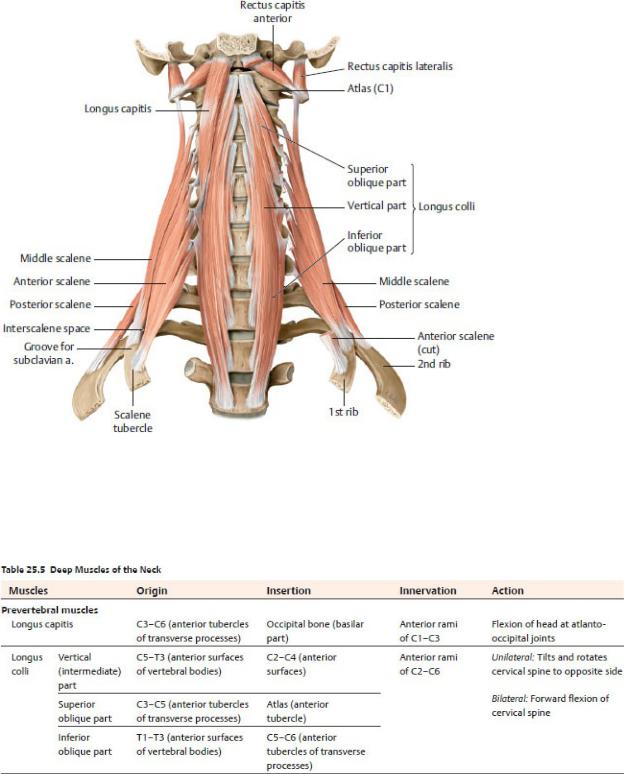

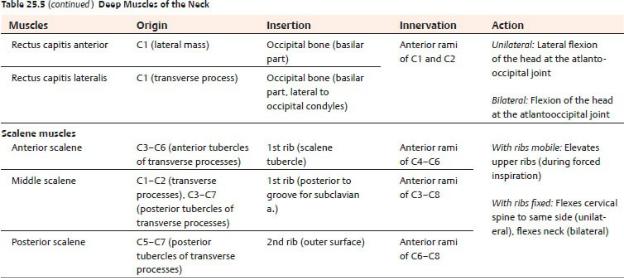

—The deep muscles of the neck lie deep to the prevertebral fascia and include the prevertebral and scalene muscles (Fig. 25.5; Table 25.5).

BOX 25.1: CLINICAL CORRELATION

CONGENITAL TORTICOLLIS

Congenital torticollis (wryneck) is a condition in which one of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles is abnormally short, causing the head to tilt to one side with the chin pointing upward to the opposite side. This shortening is thought to be the result of trauma at birth (tears or stretching of the SCM muscle) causing bleeding and swelling within the muscle and subsequent scar tissue formation.

Fig. 25.3 Superficial musculature of the neck

Left lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.4 Suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles

Anterior view. The sternohyoid has been cut on the right side. See Table 27.9 for the suprahyoid muscles. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.5 Deep muscles of the neck

Prevertebral and scalene muscles, anterior view. Removed from left side: Longus capitis and anterior scalene. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

25.4 Nerves of the Neck

Nerves of the neck include cervical and thoracic spinal nerves, nerves from the cervical sympathetic trunk, and cranial nerves.

Cervical Nerves

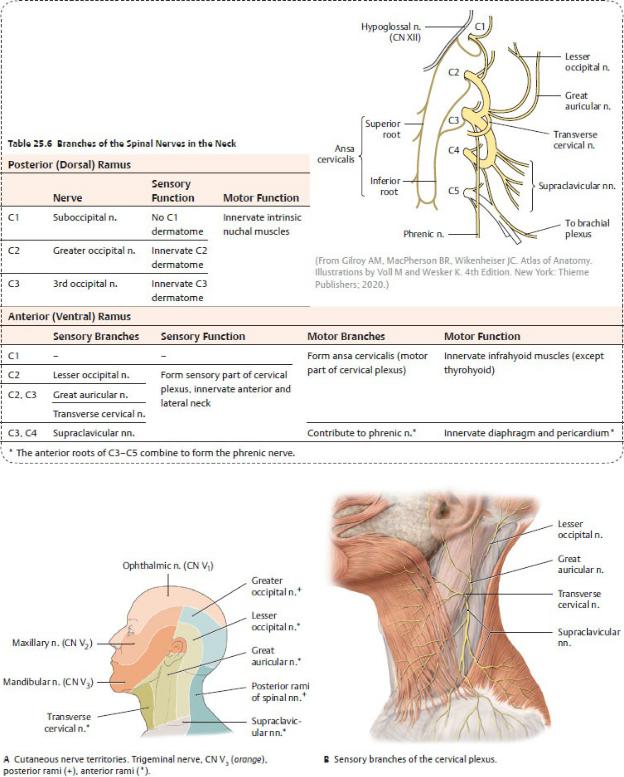

The C1–C4 spinal nerves supply the regions of the neck (Table 25.6).

—Anterior rami of C1–C4 cervical spinal nerves form the cervical plexus, which has sensory and motor components.

•The sensory nerves of the plexus, the lesser occipital (C2), great auricular (C2–C3), transverse cervical (C2–C3), and supraclavicular nerves (C3–C4), innervate the skin of the anterior and lateral neck and lateral scalp. They emerge from behind the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a location known as the nerve point of the neck (or Erb’s point) (Fig. 25.6).

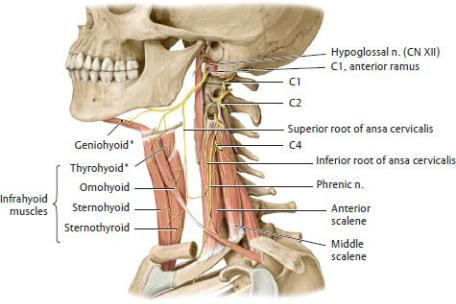

•The ansa cervicalis (C1–C3), the motor part of the plexus, which has a superior and inferior root, innervates all of the infrahyoid muscles except the thyrohyoid and usually lies anterior to the internal jugular vein (Fig. 25.7).

—The phrenic nerve, which arises from anterior rami of C3–C5 spinal nerves, descends on the surface of the anterior scalene muscle and enters the thorax, where it supplies the diaphragm with sensory and motor innervation. It also transmits sensation from the mediastinal and diaphragmatic pleura and fibrous and parietal pericardium.

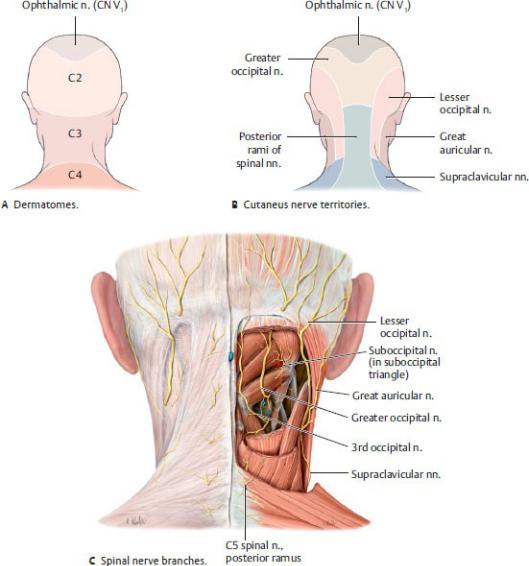

—Posterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C1 through C3 form three nerves

that provide motor and cutaneous innervation to the posterior neck and scalp: the suboccipital (C1), greater occipital (C2), and 3rd occipital nerves (C3) (Fig. 25.8).

Brachial Plexus

The brachial plexus, which innervates the upper limb, forms from the anterior rami of C5–T1. It emerges through the interscalene groove (the space between the anterior and middle scalene muscles) in the lateral region of the neck before continuing into the axilla (see Section 18.4). Normally four branches arise from the supraclavicular part of the plexus to supply muscles of the shoulder and pectoral girdle as it traverses the neck: the dorsal scapular n., suprascapular n., n. to the subclavius, and long thoracic n.

The Cervical Sympathetic Trunk

The cervical sympathetic trunk, a continuation of the thoracic sympathetic trunk, extends into the neck to the level of the C1 vertebra, where it lies anterolateral to the vertebral column and posterior to the carotid sheath (see Figs. 25.18 and

25.20).

—The cervical sympathetic trunk receives no white rami communicans from cervical spinal nerves. The preganglionic fibers that synapse in the cervical ganglia originate in thoracic spinal nerves and ascend in the sympathetic trunk to the cervical region.

Fig. 25.6 Sensory innervation of the anterolateral neck

Left lateral view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme

Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.7 Motor nerves of the cervical plexus

Left lateral view. *Innervated by the anterior ramus of C1 (distributed by the hypoglossal n.). (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.8 Sensory innervation of the nuchal region

Posterior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—Postganglionic fibers from the cervical sympathetic ganglia are distributed along three routes:

•Via gray rami communicans to join cervical spinal nerves

•Via cervical cardiac (cardiopulmonary) nerves to the cardiac plexus in the thorax

•Via sympathetic nerve plexuses surrounding vessels (periarterial plexuses), especially along the external carotid, internal carotid, and vertebral arteries, to supply structures of the head and neck (see Section

26.4)

—The cervical sympathetic trunk has superior, middle, and inferior ganglia.

•The superior cervical ganglion lies anterior to C1 vertebra and posterior to the internal carotid artery. Its branches include

◦the superior cervical sympathetic cardiac nerve,

◦branches to the pharyngeal nerve plexus,

◦an internal carotid nerve that forms the internal carotid plexus, and

◦an external carotid nerve that forms the external carotid plexus.

◦gray rami communicans that join anterior rami of C1–C4 spinal nerves.

•The middle cervical ganglion lies at the level of the C6 vertebra and gives off the middle cervical sympathetic cardiac nerve, which joins the cardiac plexus in the thorax, and gray rami communicans to anterior rami of C5 and C6 spinal nerves.

•The inferior cervical ganglion usually combines with the most superior thoracic ganglion (T1) to form the stellate ganglion, which lies anterior to the transverse process of the C7 vertebra. It gives off the inferior cervical sympathetic cardiac nerve, which descends into the thorax, and gray rami communicans to anterior rami of C7 and C8 spinal nerves.

Cranial Nerves in the Neck

Four of the cranial nerves are found in the neck.

—The glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve [CN] IX) sends branches to the tongue and pharynx in the head and descends into the neck to innervate the carotid body and carotid sinus (see Fig. 26.28). It innervates one muscle, the stylopharyngeus.

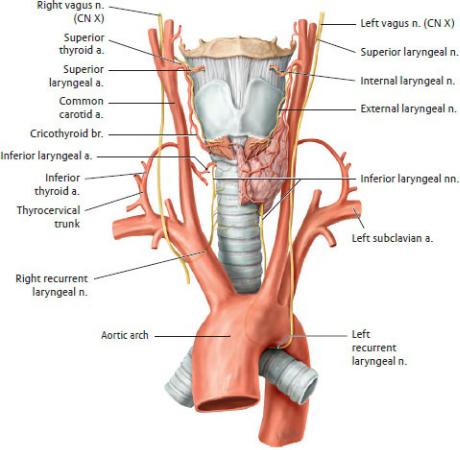

—The vagus nerve (CN X) descends within the carotid sheath in the neck before entering the thorax. Its branches to cervical structures arise from both thoracic and cervical parts of the nerve (see Fig. 26.30).

•A superior laryngeal nerve arises from the cervical part of each vagus nerve and innervates the upper larynx through its internal and external branches.

•The right recurrent laryngeal nerve arises from the inferior cervical part of the right vagus nerve and recurs around the subclavian artery in the neck.

•The left recurrent laryngeal nerve arises from the thoracic part of the left vagus nerve. It recurs around the arch of the aorta and ascends in the

neck between the trachea and esophagus.

•Cervical cardiac nerves carry visceral motor (presynaptic parasympathetic) fibers and visceral sensory fibers to the cardiac plexus.

—The spinal accessory nerve (CN XI), which is derived from roots of the upper cervical spinal cord segments, enters the skull through the foramen magnum. After exiting the skull through the jugular foramen, it innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle, then crosses the lateral region of the neck to innervate the trapezius muscle (see Fig. 26.31).

•The cranial root joins the vagus nerve.

•The spinal root innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle, then crosses the lateral region of the neck to innervate the trapezius muscle.

—The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), which exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal and courses anteriorly to the submandibular region, enters the oral cavity to innervate muscles of the tongue.

•Along its course, fibers from C1 join the hypoglossal nerve briefly, eventually diverging from it to innervate the geniohyoid and thyrohyoid muscles and to form the superior root of the ansa cervicalis (see Fig. 25.7).

25.5 Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx in the neck to the stomach in the abdomen (see Section 7.7).

—The cervical esophagus begins at the C6 vertebral level, which corresponds to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. The cervical esophagus is posterior to the trachea, anterior to the cervical vertebrae, and continuous with the laryngopharynx superiorly.

—At the pharyngoesophageal junction, the cricopharyngeus, the lowest part of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, forms the superior esophageal sphincter.

—The inferior thyroid arteries, branches of the subclavian arteries via the thyrocervical trunks, supply the cervical part of the esophagus. Veins of similar name accompany the arteries.

—Lymphatic vessels from the cervical esophagus drain to paratracheal and deep cervical nodes.

—The recurrent laryngeal nerves, branches of the vagus nerve (CN X), and vasomotor fibers from the cervical sympathetic trunk innervate the esophagus in the neck.

25.6 Larynx and Trachea

The larynx, part of the upper airway, is responsible for sound production. It communicates superiorly with the pharynx and inferiorly with the trachea and lies anterior to the C3–C6 vertebrae. The trachea, the upper part of the tracheobronchial tree, descends into the thorax, where it is continuous with the bronchi of the lungs.

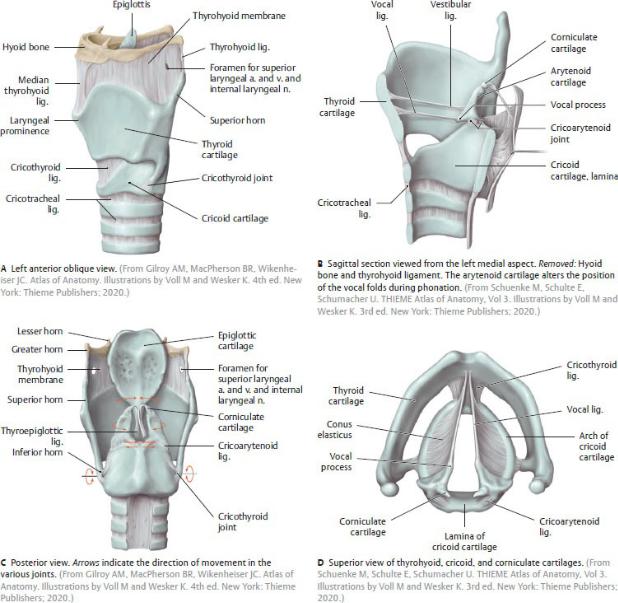

Laryngeal Skeleton

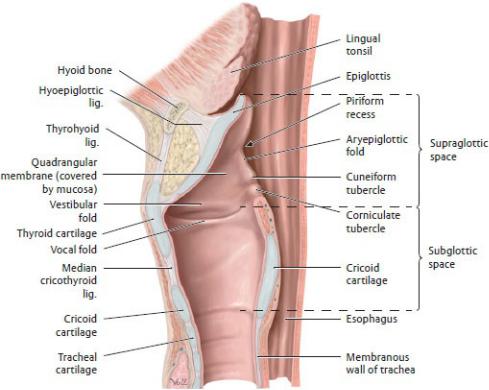

Three single cartilages and two sets of paired cartilages form the laryngeal skeleton (Fig. 25.9). All except the epiglottis (elastic cartilage) are formed of hyaline cartilage.

—The thyroid cartilage, the largest of the nine cartilages, has two laminae that join at the midline to form a laryngeal prominence (Adam’s apple). The superior horn of the thyroid cartilage attaches to the hyoid bone, and the inferior horn articulates with the cricoid cartilage at the cricothyroid joint.

—The cricoid cartilage, the only part of the laryngeal skeleton to form a complete ring around the airway, articulates superiorly with the thyroid cartilage and is attached inferiorly to the first tracheal ring. The anterior part of the cricoid cartilage, the arch, is short, and the lamina, its posterior part, is tall.

—The epiglottis, a leaf-shaped cartilage that forms the anterior wall of the laryngeal inlet at the root of the tongue, is attached inferiorly to the thyroid cartilage and anteriorly to the hyoid bone.

Fig. 25.9 Structure of the larynx

—The paired pyramidal arytenoid cartilages, which articulate with the superior border of the cricoid lamina, have an apex that articulates with the tiny corniculate cartilages and a vocal process that attaches to the thyroid cartilage through the vocal ligaments.

—The small, paired corniculate and cuneiform cartilages appear as tubercles within the aryepiglottic fold. Although the corniculate cartilages articulate with the arytenoids, the cuneiform cartilages do not articulate with the other cartilages.

Membranes and Ligaments of the Larynx

Membranes of the larynx connect the laryngeal cartilages to each other and to the hyoid bone and trachea (Figs. 25.9, 25.10, 25.11).

—The thyrohyoid membrane attaches the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone superiorly.

—The cricotracheal ligament attaches the cricoid cartilage to the first tracheal ring inferiorly.

—The quadrangular membrane extends posteriorly from the lateral border of the epiglottis to the arytenoid cartilage on each side.

•The superior free margin of this membrane forms the aryepiglottic ligament, which, when covered by mucosa, is known as the aryepiglottic fold.

•The inferior free margin is the vestibular ligament, which, when covered by mucosa, is known as the vestibular fold or false vocal cord.

—The cricothyroid membrane connects the cricoid and thyroid cartilages and extends superiorly deep to the thyroid cartilage as the conus elasticus

(see Figs. 25.9D and 25.12C).

—The free superior border of the conus elasticus forms the vocal ligament, which extends from the midpoint of the thyroid cartilage to the vocal processes of the arytenoid cartilage. The vocal ligament and the vocalis muscle form the vocal fold or vocal cord.

BOX 25.2: CLINICAL CORRELATION

TRACHEOSTOMY AND CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY

When the upper airway is obstructed, airway access can be reestablished using two different approaches. Tracheostomy is a surgical procedure in which a tracheostomy tube is inserted through an incision in the proximal trachea. This procedure is generally used for long-term management of the airway. Cricothyroidotomy is a related procedure in which an incision is made in the cricothyroid membrane. This procedure, usually performed in emergency situations, is less technically difficult than tracheostomy and has fewer complications.

Fig. 25.10 Cavity of the larynx

Midsagittal section viewed from the left side. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

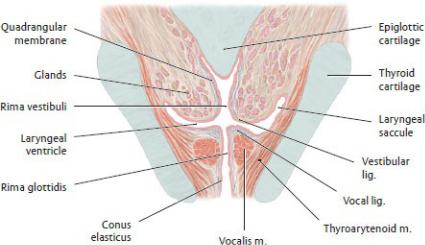

Laryngeal Cavity

The laryngeal cavity begins at the laryngeal inlet and extends to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (see Figs. 25.10 and 25.11).

—The vestibular and vocal folds define spaces within the laryngeal cavity.

•The supraglottic space (laryngeal vestibule) or supraglottic space lies above the vestibular folds.

•The rima vestibuli is the aperture between the two vestibular folds.

•The laryngeal ventricles are recesses of the laryngeal cavity between the vestibular and vocal folds.

•Laryngeal saccules are the blind ends of the laryngeal ventricles.

•The rima glottidis is the aperture between the two vocal folds.

•The subglottic space (infraglottic cavity) is the inferior part of the laryngeal cavity, which lies below the vocal folds and extends to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage.

Fig. 25.11 Vestibular and vocal folds

Coronal section. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—Sound is produced as air passes through the laryngeal cavity between the vocal folds. Variations in sound arise from changes in the position, tension, and length of these folds.

—The vestibular folds protect the airway but have no role in sound production.

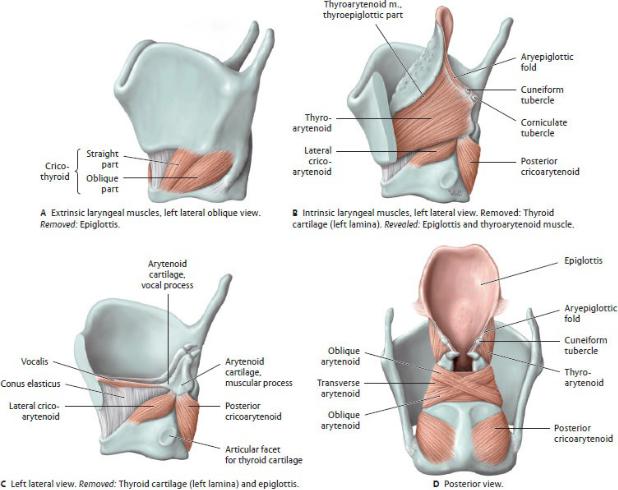

Muscles of the Larynx

The larynx has extrinsic and intrinsic muscle groups.

—Extrinsic muscles are attached to the hyoid bone and move the larynx and hyoid bone together. These include the suprahyoid muscles (see Table 27.9), which form the floor of the mouth and elevate the larynx, and the infrahyoid muscles (see Table 25.4), which depress the larynx.

—Intrinsic muscles move the laryngeal cartilages, which changes the length and tension of the vocal ligaments and size of the rima glottidis (Table 25.7;

Fig. 25.12).

—Two muscles are particularly clinically and anatomically significant:

•The posterior cricoarytenoid muscle is the only muscle that abducts the vocal folds and opens the rima glottidis.

•The cricothyroid muscle, innervated by the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, is the only intrinsic muscle that is not innervated by the inferior laryngeal nerve (a continuation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve).

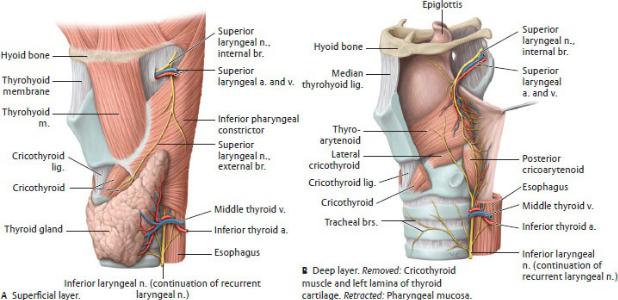

Neurovasculature of the Larynx (Figs. 25.13, 25.15, 25.16)

—The superior and inferior laryngeal arteries are branches of the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, respectively. Veins of the larynx follow the laryngeal arteries and join the thyroid veins.

—The superior and inferior laryngeal branches of the vagus nerve (CN X) provide all of the motor and sensory innervation of the larynx.

•The superior laryngeal nerve splits into an internal sensory branch, which supplies the mucosa of the vestibule and superior surface of the vocal folds, and an external motor branch, which innervates the cricothyroid muscle.

•The inferior laryngeal nerve, a continuation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, supplies the mucosa of the infraglottic larynx and innervates all intrinsic muscles of the larynx except the cricothyroid.

BOX 25.3: CLINICAL CORRELATION

RECURRENT LARYNGEAL NERVE PARALYSIS WITH THYROIDECTOMY

The recurrent laryngeal nerves in the neck are vulnerable to damage during thyroidectomy because they run immediately posterior to the thyroid gland. Unilateral damage results in hoarseness; bilateral damage causes respiratory distress and aphonia (inability to speak). Aspiration pneumonia may occur as a complication.

Trachea

The trachea, the extension of the airway inferior to the larynx, extends from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage to the level of the T4–T5 intervertebral disks in the thorax, where it bifurcates into the two primary bronchi of the lungs (see Section 7.7). In the cervical region (see Fig. 25.18)

—it lies deep to the superficial and deep cervical fascia, and sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles.

—the isthmus of the thyroid gland crosses its 2nd to 4th tracheal cartilages. The lobes of the thyroid are lateral to it and descend to the fifth or sixth tracheal cartilage.

—the esophagus lies posterior and separates it from the vertebral column.

Table 25.7 Actions of the Laryngeal Muscles

Muscle |

Action |

Effect on Rima |

|

|

|

|

|

Glottidis |

Cricothyroid m.* |

Tightens the vocal |

None |

|

folds |

|

Vocalis m. |

|

|

|

|

|

Thyroarytenoid m. |

Adducts the vocal |

Closes |

|

folds |

|

|

|

|

Transverse |

|

|

arytenoid m. |

|

|

|

|

|

Posterior |

Abducts the vocal |

Opens |

cricoarytenoid m. |

folds |

|

|

|

|

Lateral |

Adducts the vocal |

Closes |

cricoarytenoid m. |

folds |

|

*The cricothyroid m. is innervated by the external laryngeal n. All other intrinsic mm. are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal n.

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.12 Laryngeal muscles

The laryngeal muscles move the laryngeal cartilages relative to one another, affecting the tension and/or position of the vocal folds. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.13 Neurovasculature of the larynx

Left lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—the common carotid arteries ascend lateral to it.

—the recurrent laryngeal nerves ascend lateral or posterolateral to it (in the groove between the trachea and esophagus).

—it is supplied by the inferior thyroid artery and drained by the inferior thyroid veins.

—lymph drains to pretracheal and paratracheal nodes.

—it receives innervation from branches of the vagus n. and the sympathetic trunk.

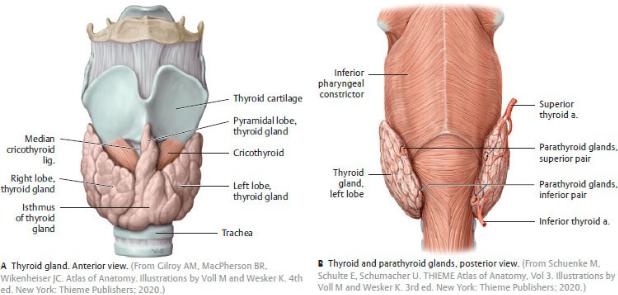

25.7 Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

The thyroid and parathyroid glands are endocrine glands that reside in the anterior cervical region (Fig. 25.14).

The Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland, the largest endocrine gland in the body, secretes thyroid hormone, which regulates the rate of metabolism, and calcitonin, which regulates the metabolism of calcium.

—The thyroid lies deep to the sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles (infrahyoid muscles) and anterolateral to the larynx and trachea between C5

and T1 vertebral levels.

—The thyroid has right and left (lateral) lobes connected by a narrow isthmus that lies anterior to the second and third tracheal rings.

—A pyramidal lobe, present in ~ 50% of the population, is a remnant of the embryonic thyroglossal duct that extends from the isthmus toward the hyoid bone.

BOX 25.4: DEVELOPMENTAL CORRELATION

THYROGLOSSAL DUCT CYST

A thyroglossal duct cyst is a fluid-filled cavity in the midline of the neck, just inferior to the hyoid bone. It results from the proliferation of epithelium left behind from the thyroglossal duct during the descent of the thyroid gland from its embryonic origin on the tongue to its postnatal position in the neck. The cyst can enlarge and press on the trachea and esophagus, in which case it can be surgically removed.

—A fibrous capsule encloses the thyroid gland. The pretracheal fascia of the neck lies outside the thyroid capsule (see Fig. 25.2).

The Parathyroid Glands

Parathyroid glands, small, ovoid endocrine glands that lie on the posterior surface of the thyroid gland, secrete parathormone, which regulates the metabolism of phosphorus and calcium (Fig. 25.14B).

—There are normally four glands, two superior and two inferior, although the number can range from two to six glands.

—The superior parathyroid glands are constant in position near the lower border of the cricoid cartilage. The position of the inferior parathyroid glands may vary, ranging from the lower pole of the thyroid gland to the superior mediastinum.

Neurovasculature of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

—The superior thyroid artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, and the inferior thyroid artery from the thyrocervical trunk supply the thyroid gland (Fig. 25.15). The inferior thyroid artery is usually the main supply to the parathyroid glands.

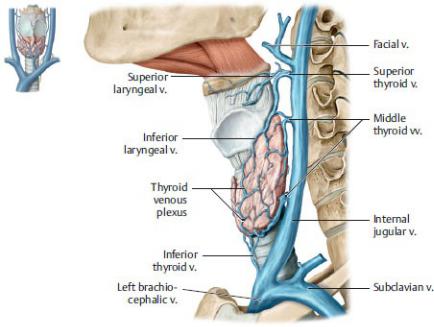

—Superior and middle thyroid veins drain into the internal jugular veins; inferior thyroid veins drain into the brachiocephalic veins in the mediastinum (Fig. 25.16). Venous drainage from the parathyroid glands

joins the thyroid veins.

—Lymphatic vessels of the thyroid may drain directly into the superior and inferior deep cervical nodes or indirectly, passing first through prelaryngeal, pretracheal, and paratracheal nodes.

—The parathyroid glands drain with the thyroid into the inferior deep cervical and paratracheal lymph nodes.

—Cardiac and superior and inferior thyroid sympathetic plexuses arise from the superior, middle, and inferior cervical sympathetic ganglia to supply vasomotor innervation to the thyroid and parathyroid glands.

—The thyroid and parathyroid glands are under hormonal control and therefore lack secretomotor innervation.

Fig. 25.14 Thyroid and parathyroid glands

Fig. 25.15 Arteries and nerves of the larynx, thyroid, and parathyroids

Anterior view. Removed: Thyroid gland (right half). (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 25.16 Veins of the larynx, thyroid, and parathyroid glands

Left lateral view. Note: The inferior thyroid vein generally drains into the left brachiocephalic vein. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

25.8 Topography of the Neck

Fig. 25.17 Topography of the anterior cervical region (continued on page 470)

Anterior view.

Fig. 25.17 (continued) Topography of the anterior cervical region

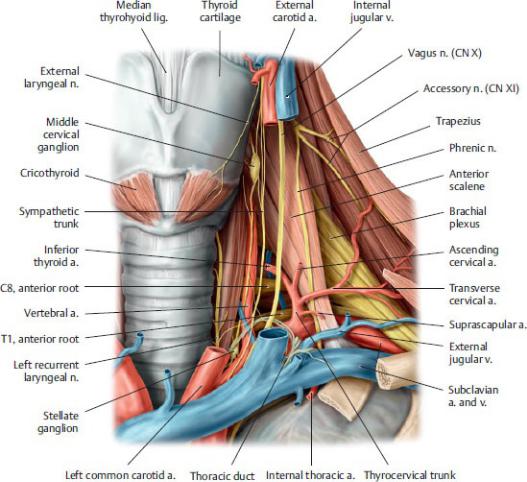

Fig. 25.18 Root of the neck

Anterior view, left side. The thyroid gland has been removed and the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein have been cut to reveal the deep structures in the root of the neck. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

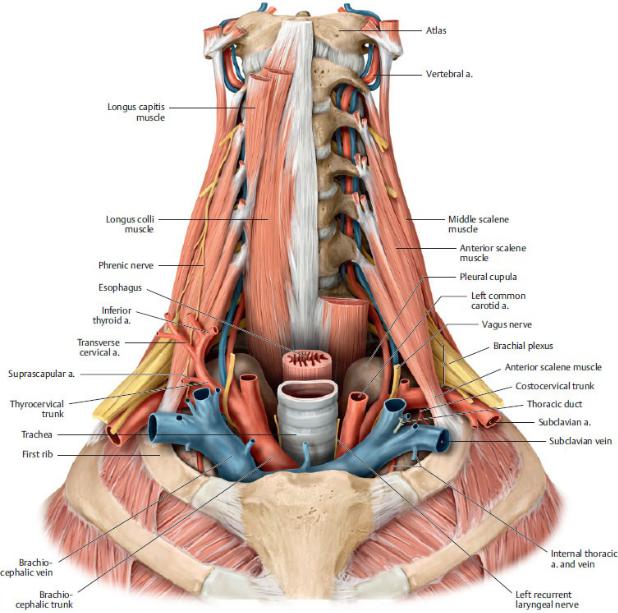

Fig. 25.19 The thoracic inlet

Anterior view. The viscera of the neck have been removed and the esophagus, trachea, common carotid artery and jugular veins have been dissected to show the relations of structures passing through the thoracic inlet. The prevertebral muscles on the left side have been cut to show the course of the vertebral artery. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

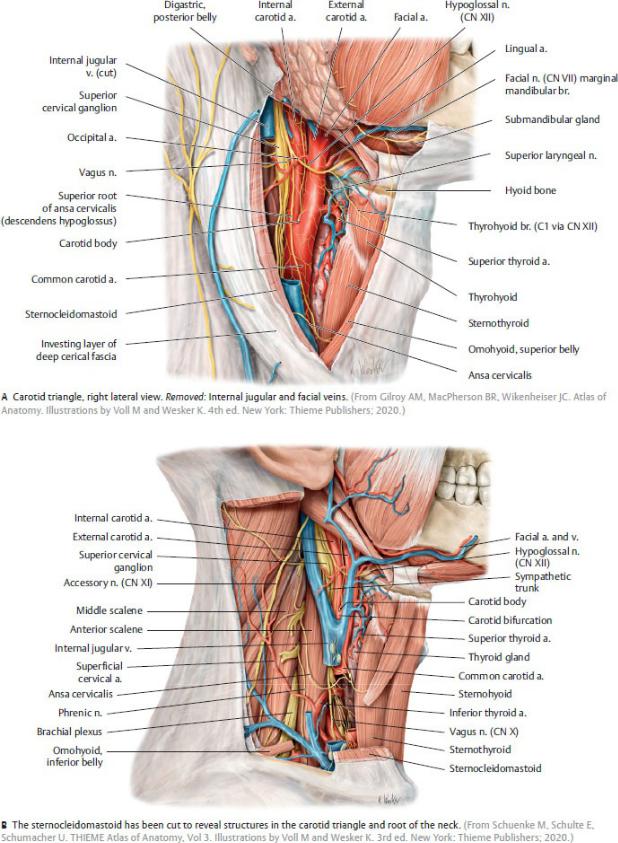

Fig. 25.20 Lateral cervical region

Right lateral view.