- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •1 Introduction to Anatomic Systems and Terminology

- •2 Clinical Imaging Basics Introduction

- •3 Back

- •4 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Spine

- •5 Overview of the Thorax

- •6 Thoracic Wall

- •7 Mediastinum

- •8 Pulmonary Cavities

- •9 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Thorax

- •10 The Abdominal Wall and Inguinal Region

- •12 Abdominal Viscera

- •13 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Abdomen

- •14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

- •15 Pelvic Viscera

- •16 The Perineum

- •18 Overview of the Upper Limb

- •19 Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb

- •20 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Upper Limb

- •21 Overview of the Lower Limb

- •22 Functional Anatomy of the Lower Limb

- •23 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Lower Limb

- •24 Overview of the Head and Neck

- •25 The Neck

- •26 Meninges, Brain, and Cranial Nerves

- •29 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Head and Neck

- •Index

14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

The pelvic region is the area of the trunk between the abdomen and lower limb. It includes the pelvic cavity, the bowl-shaped space enclosed by the bony pelvis, and the perineum, the diamond-shaped area inferior to the pelvic floor and between the upper aspects of the thighs.

14.1 General Features

— Table 14.1 provides an overview of the divisions of the pelvis and perineum.

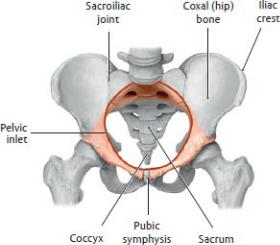

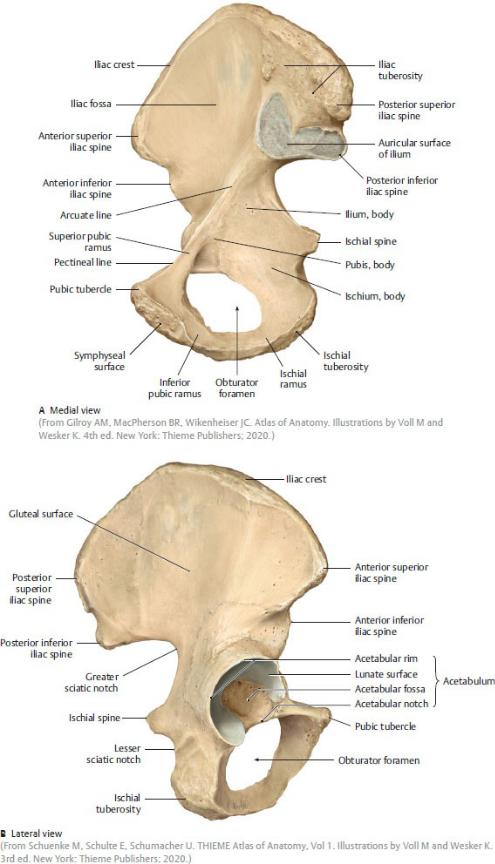

•The bony pelvis, or pelvic girdle, encloses the pelvic cavity. Its superior bony landmark is the iliac crest (Fig. 14.1).

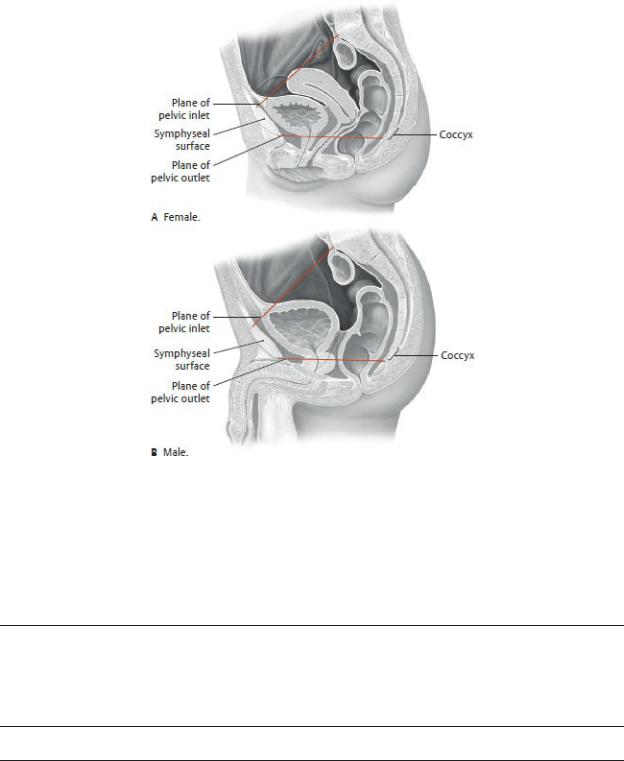

•The pelvic brim at the plane of the pelvic inlet defines the upper border of the bony true pelvis (birth canal) and separates it from the false pelvis above. A pelvic outlet defines the lower border of the true pelvis

(Fig. 14.2).

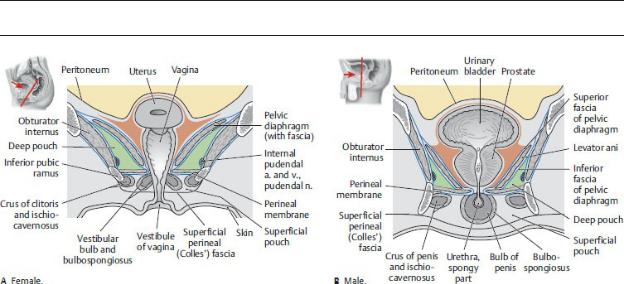

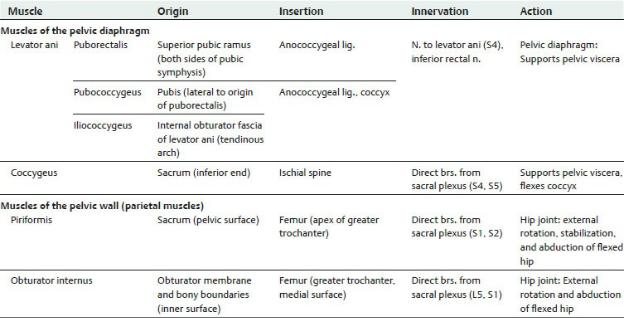

•The muscular floor of the pelvic cavity, the pelvic diaphragm, separates the true pelvis from the perineum, which lies below it (Fig. 14.3).

•The diamond-shaped perineum is subdivided into an anterior urogenital triangle and a posterior anal triangle (Fig. 14.4).

•A membranous perineal membrane divides the urogenital triangle into two small spaces:

◦an upper deep pouch, which includes the anterior recesses of the ischioanal fossae and which is bounded by the perineal membrane inferiorly, the inferior fascia of the pelvic diaphragm superiorly, and the obturator fascia laterally and

◦a lower superficial pouch bounded superiorly by the perineal membrane, inferiorly by the superficial perineal fascia, and laterally by the ischiopubic rami (Fig. 14.3).

Fig. 14.1 Pelvic girdle

Anterosuperior view. The pelvic girdle consists of the two coxal bones and the sacrum. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

The perineal membrane is not present in the anal triangle (see Fig. 15.24).

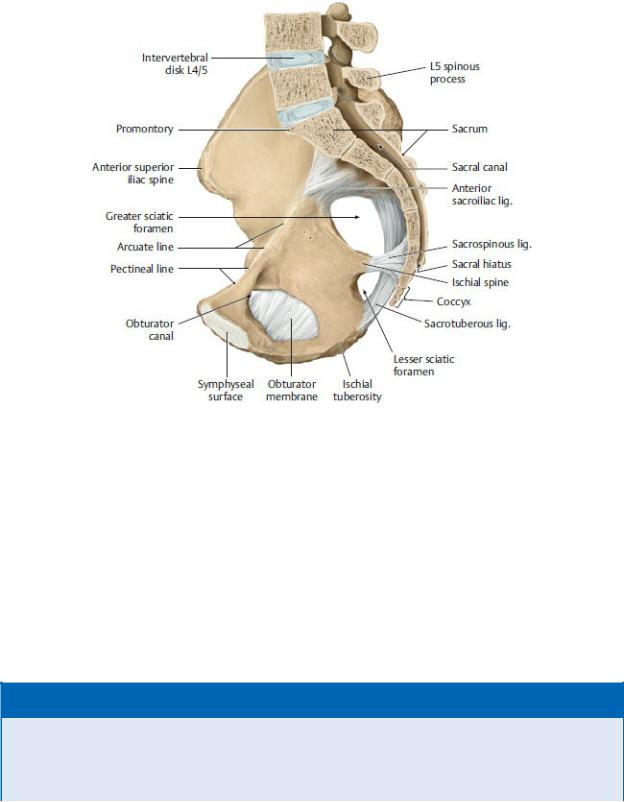

—The pelvic inlet and pelvic outlet are apertures of the bony pelvis (Fig. 14.5).

•The pelvic inlet (pelvic brim), the superior aperture, is defined by a line that extends from the promontory of the sacrum, along the arcuate line of the ilium and pectineal line of the pubic bone, to the superior border of the pubic symphysis.

•The pelvic outlet, the inferior aperture, is defined by a line that connects the coccyx, sacrotuberous ligaments, ischial tuberosities, ischiopubic rami, and inferior border of the pubic symphysis.

—The cavities of the true pelvis and the false pelvis are continuous with each other but contain different viscera.

•The true pelvis lies below the pelvic brim and is bounded inferiorly by the muscular pelvic floor. In the adult, this space houses the bladder, rectum, and pelvic genital structures.

•The false pelvis is the lower part of the abdominal cavity that lies above the pelvic brim and is bounded on each side by the iliac fossa. It contains the cecum, appendix, sigmoid colon, and loops of the small intestine.

Fig. 14.2 True and false pelvis

Midsagittal sections, viewed from the left side. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Table 14.1 Divisions of the Pelvis and Perineum

The levels of the pelvis are determined by bony landmarks (iliac alae and pelvic inlet/brim). The contents of the perineum are separated from the true pelvis by the pelvic diaphragm and two fascial layers.

Iliac crest

|

• |

Ileum (coils) |

|

• |

Cecum and appendix |

False pelvis |

• |

Sigmoid colon |

• |

Common and external iliac |

|

|

• |

aa. and vv. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lumbar plexus (branches) |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pelvic inlet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Pelvis |

• |

Distal ureters |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

• |

Urinary bladder |

|

|

|

||

|

|

• |

Rectum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• ♀: vagina, |

uterus, |

uterine |

||||

|

True pelvis |

• |

tubes, and ovaries |

|

|

|||

|

♂: ducti deferens, seminal |

|||||||

|

|

|

glands, and prostate |

|

||||

|

|

• Internal iliac a. and v. and |

||||||

|

|

• |

branches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sacral plexus |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

• |

Inferior hypogastric plexus |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

coccygeus) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

• |

External urethral sphincter |

|||||

|

|

• |

Compressor |

urethrae |

and |

|||

|

|

|

urethrovaginal |

sphincter |

||||

|

|

• |

(females) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urethra (membranous part |

||||||

|

|

• |

in males) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transverse |

perineal |

m. |

||||

|

Deep pouch |

|

(males), |

smooth |

|

muscle |

||

|

|

(female) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulbourethral |

|

glands |

||||

|

|

• |

(male) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anterior |

|

recess |

of |

|||

|

|

|

ischioanal fat pads |

|

|

|||

|

|

• Internal |

pudendal |

aa. and |

||||

|

|

|

vv., pudendal |

nn. |

and |

|||

|

|

|

branches |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perineal membrane |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Perineum |

• |

Ischiocavernosus, |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

bulbospongiosus, |

|

|

and |

||

|

|

superficial |

transverse |

Superficial pouch |

• |

perineal mm. |

|

Urethra (spongy in males) |

|||

|

• Clitoris and root of penis |

||

|

• Bulbs of the vestibule |

||

|

• |

Greater vestibular glands |

|

|

• Internal pudendal a. and v., |

||

|

|

pudendal n. and branches |

|

|

|

|

|

Superficial perineal |

|

|

|

(Colles’) fascia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subcutaneous |

• |

Fat |

|

perineal space |

|

|

|

Skin

Fig. 14.3 Pelvis and urogenital triangle of the perineum

Coronal section, anterior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.4 Regions of the perineum

Lithotomy position, caudal (inferior) view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.5 Pelvic inlet and outlet

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The peritoneum of the abdominal cavity continues into the pelvic cavity.

•The peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall drapes over the bladder, uterus, rectum, and pelvic walls, but it does not extend as far inferiorly as the pelvic floor.

•Deep pelvic viscera that lie below the peritoneum occupy a subperitoneal space that is continuous with the retroperitoneum of the abdomen (see Fig. 14.3).

—The perineum lies inferior to the pelvic cavity (see Fig. 14.4).

•The pelvic outlet forms the perimeter of the perineum, the pelvic diaphragm forms its roof, and, inferiorly, perineal skin forms its floor.

•The urogenital triangle of the perineum contains the external genital structures and openings for the urethra and vagina (in females).

•The anal triangle of the perineum contains the anal opening and anal canal, surrounded by the external anal sphincter.

—The ischioanal fossae, wedge-shaped, fat-filled spaces of the anal triangle, lie on either side of the anal canal and extend anteriorly into a small recess of the urogenital triangle (see Fig. 15.24; Section 16.5).

BOX 14.1: CLINICAL CORRELATION

PELVIC DIAMETERS: TRUE CONJUGATE, DIAGONAL CONJUGATE

Pelvic measurements are important obstetric predictors of ease of vaginal delivery. The true (obstetrical) conjugate, the narrowest

anteroposterior diameter of the birth canal, is measured from the posterior superior margin of the pubic symphysis to the tip of the sacral promontory (~ 11 cm). Because this distance is difficult to measure accurately, the diagonal conjugate is used to estimate it. This is measured from the lower border of the pubic symphysis to the tip of the sacral promontory (~ 12.5 cm).

Right hemipelvis

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

14.2 The Bony Pelvis

The bony pelvis, or pelvic girdle, consists of the sacrum, the coccyx, and the two coxal (hip) bones. It protects the pelvic viscera, stabilizes the back, and provides an attachment site for the lower limbs. Pelvic joints create the circular configuration of the pelvic girdle, which is maintained by strong pelvic ligaments (see Fig. 14.1).

—The sacrum and coccyx, the lowest segments of the vertebral column, constitute the posterior wall of the pelvic girdle.

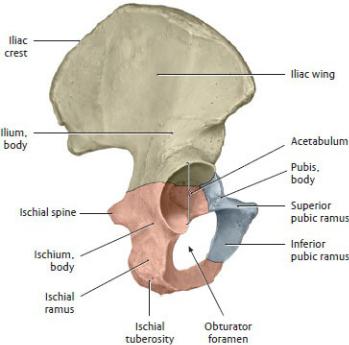

—Each hip bone, the lateral parts of the pelvic girdle, is formed by the fusion of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis (Fig. 14.6). Features of the hip bones (Fig. 14.7) include the following:

•The superior and inferior pubic rami, which join anteriorly but diverge laterally around the large obturator foramen

•The ischial spine posteriorly, which separates the greater and lesser sciatic notches

•The ischial ramus, which fuses with the inferior pubic ramus anteriorly and ends as the ischial tuberosity posteriorly

•The iliac wing, which is concave anteriorly, forming the iliac fossa. The superior edge of the iliac wing, the iliac crest, ends anteriorly as the anterior superior iliac spine and posteriorly as the posterior superior iliac spine.

•An arcuate line on the internal surface, which bisects the ilium and continues anteriorly to join with the pectineal line of the pubis. Both lines form part of the pelvic inlet (also known as the linea terminalis).

•A deep, cup-shaped depression, the acetabulum, on the lateral surface, which articulates with the femur of the lower limb

—The joints of the pelvic girdle include the following (see Fig. 14.1):

•The paired sacroiliac joints, which are synovial joints between the auricular surfaces of the sacrum and the hip bones

•The pubic symphysis, an immobile cartilaginous joint in the anterior midline that joins the pubic portions of the hip bones with an intervening fibrocartilaginous disk

Fig. 14.6 Triradiate cartilage of the coxal bone

Right coxal bone, lateral view. The coxal bone consists of the ilium, ischium,

and pubis. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.7 Coxal (hip) bone

Right coxal bone (male).

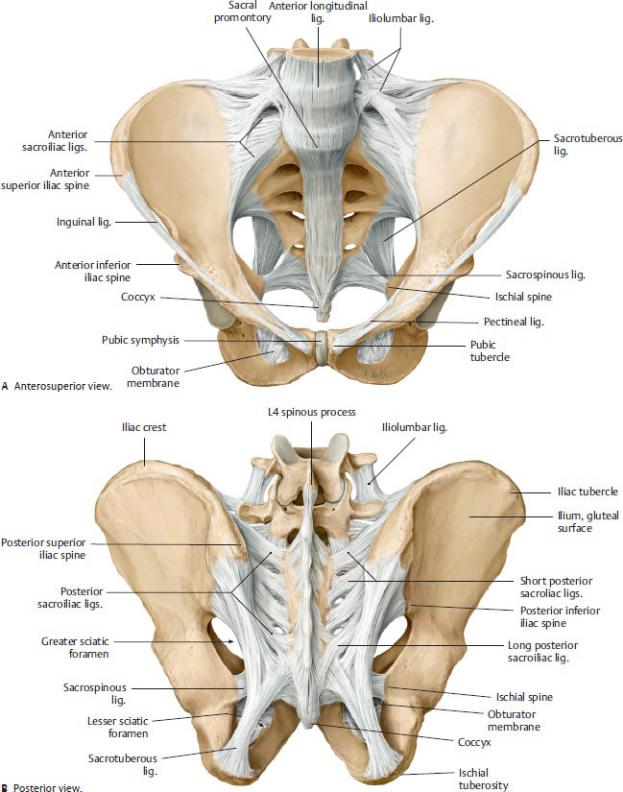

—Ligaments that support pelvic joints (Fig. 14.8) include the following:

•The strong anterior, posterior, and interosseous sacroiliac ligaments that support the sacroiliac joints

•The iliolumbar ligaments that stabilize the junction between the lumbar spine and sacrum

•Two pairs of posterior ligaments that secure the sacrum and hip bone articulations and resist posterior displacement of the sacrum

1.The sacrotuberous ligaments originate on the sacrum and insert on the ischial tuberosities.

2.The sacrospinous ligaments originate on the sacrum and insert on the ischial spines.

—The pelvic bones and ligaments form openings that allow pelvic vessels, nerves, and muscles to connect to adjacent regions (Fig. 14.9).

•The greater sciatic foramen is a posterior opening that connects the pelvis to the gluteal region (the buttocks).

Fig. 14.8 Ligaments of the pelvis

Male pelvis. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of

Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.9 Pelvic openings

Right half of male pelvis, medial view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•The lesser sciatic foramen is a passageway between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments that connects the gluteal region and perineum.

•An obturator membrane covers most of the bony obturator foramen, leaving a small obturator canal through which the obturator nerve and vessels pass into the thigh.

BOX 14.2: CLINICAL CORRELATION

LAXITY OF LIGAMENTS AND INCEASED MOBILITY DURING PREGNANCY

During the final trimester of pregnancy, there is a marked increase in

the softness and laxity of the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac ligaments, which is attributed to increased levels of relaxin and other pregnancy hormones. This often results in some pelvic instability and the characteristic waddling gait of the third trimester. Softening of the pelvic ligaments increases the pelvic diameter, which is of benefit as the neonate negotiates the birth canal. Normal ligament integrity returns within a few months following birth.

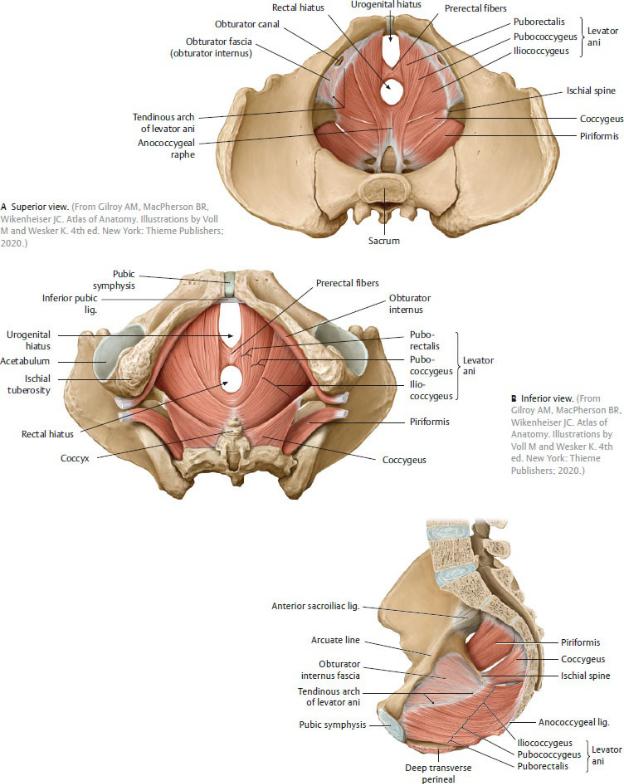

14.3 Pelvic Walls and Floor ( Table 14.2; Fig. 14.10)

—The muscles that line the pelvic walls pass into the gluteal region, where they attach to the femur (thigh bone) and act on the hip joint.

•The piriformis lines the posterior wall of the pelvis.

◦It passes from the pelvis to the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen.

◦It forms the bed for the sacral plexus and internal iliac vessels on the posterior pelvic wall.

•The obturator internus, covered by an overlying obturator fascia, lines the sidewall of the pelvis and perineum.

◦Its tendon passes from the perineum to the gluteal region through the lesser sciatic foramen.

◦A thickening of the obturator fascia, the tendinous arch of the levator ani, runs from the body of the pubis to the ischial spine.

—The funnel-shaped pelvic floor is composed of muscles, collectively known as the pelvic diaphragm, that support the pelvic viscera and resist intraabdominal pressure (i.e., pressure created during coughing, sneezing, forced expiration, defecating, and parturition). The pelvic dia-phragm is composed of the levator ani and the coccygeus muscles.

•The levator ani forms the largest part of the pelvic floor. The three muscles of the levator ani arise from the superior pubic ramus and the tendinous arch. They insert in the midline on the coccyx and along a tendinous raphe, called the anococcygeal ligament (levator plate).

◦The pubococcygeus forms the anterior part of the levator ani.

◦The iliococcygeus forms the middle part of the levator ani.

◦The puborectalis forms a muscular sling that loops around the anorectum. Normal tone of the muscle maintains the anterior angle

of the anorectum where it passes through the pelvic diaphragm. The muscle relaxes during defecation.

•The coccygeus muscle forms the posterior part of the pelvic diaphragm; it attaches to the sacrum and ischial spine and tightly adheres to the sacrospinous ligament along its entire length.

—The levator (or genital) hiatus, a gap between the puborectalis muscles on either side, allows the passage of the urethra, vagina, and rectum into the perineum.

—The inferior gluteal, superior gluteal, and lateral sacral branches of the internal iliac arteries and the median sacral branch of the abdominal aorta supply most muscles of the pelvic walls and floor (see Fig. 14.14A).

—Veins that accompany the arteries and drain the pelvic floor and walls ultimately drain to the internal iliac veins, although the lateral sacral veins may also drain to the internal vertebral venous plexus.

Fig. 14.10 Muscles of the pelvic floor

Female pelvis.

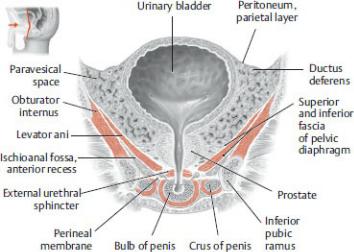

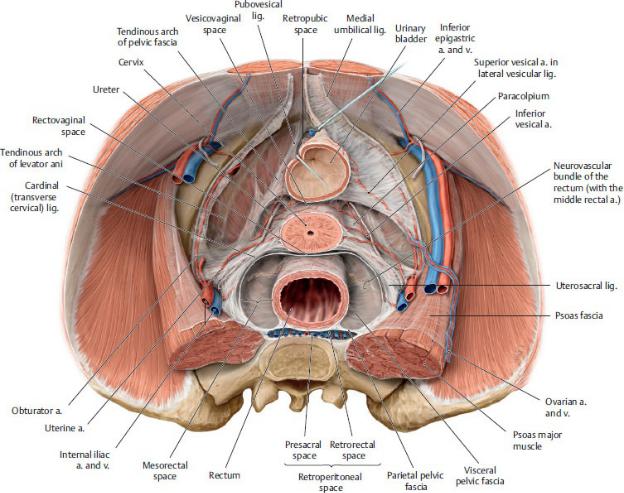

14.4 Pelvic Fascia

Pelvic fascia is a connective tissue layer located between the viscera and the muscular walls and floor of the pelvis. There are two types, membranous fascia and endopelvic fascia (Figs. 14.11 and 14.12; see also Fig. 14.3).

—Membranous pelvic fascia, usually a thin layer that adheres to the pelvic walls and viscera, has visceral and parietal layers.

•The visceral pelvic fascia surrounds the individual organs, and when in contact with the peritoneum it lies between the visceral peritoneum and the organ wall.

•The parietal pelvic fascia lines the inner surface of the muscles of the pelvic walls and floor. It is continuous with the transversalis fascia and psoas fascia of the abdomen and is named regionally for the muscle it covers (i.e., obturator fascia).

•Where the pelvic viscera pierce the pelvic diaphragm, the parietal and visceral layers merge to form a tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia. This arch runs from the pubis to the sacrum on either side of the pelvic floor. Pubovesical ligaments in the female and puboprostatic ligaments in the male are extensions of the tendinous arches that support the bladder and prostate. In females, the paracolpium—lateral connections between the visceral fascia and the tendinous arches— suspends and supports the vagina.

•Endopelvic fascia forms a loose connective tissue matrix that fills the

subperitoneal space between the visceral and parietal layers of the membranous fascia.

•Much of this fascia has a cotton candy–like consistency that pads the subperitoneal space but allows for distension of the pelvic viscera (e.g., vagina, rectum).

Fig. 14.11 Pelvic fascia

Male pelvis in coronal section, anterior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•Large supporting columns of this connective tissue extend from the pelvic walls to the rectum as the lateral ligaments of the rectum, and from the pelvic wall to the bladder as the lateral ligaments of the bladder.

•In some areas, the endopelvic fascia forms fibrous condensations [e.g., cardinal (transverse cervical) ligament] that support the pelvic viscera and their vascular and nerve plexuses.

Fig. 14.12 Fascial attachments in the female pelvis

Transverse section through the cervix, superior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

14.5 Pelvic Spaces

The peritoneum of the abdominal wall covers the superior surface of the bladder, the anterior and posterior surfaces of the uterus, and the anterolateral surfaces of the rectum. Because the peritoneum does not descend to the pelvic floor, spaces are created above the peritoneum, within the peritoneal cavity, and below the peritoneum in the subperitoneal space (Fig. 14.13).

—Peritoneal recesses, intraperitoneal spaces that are continuous with the peritoneal cavity of the abdomen and lined by the visceral peritoneum of the pelvic organs, are normally occupied by loops of small intestine and

peritoneal fluid.

•In males, a rectovesical pouch between the bladder and rectum is the lowest point in the male peritoneal cavity.

•In females, a vesicouterine pouch forms between the bladder and uterus, and a rectouterine pouch (of Douglas) forms between the uterus and rectum. The rectouterine pouch is the lowest point of the female peritoneal cavity.

—Subperitoneal recesses are extraperitoneal spaces that are continuous with the retroperitoneum of the abdomen and are filled with endopelvic fascia.

•The retropubic space (prevesical space, space of Retzius) lies between the pubic symphysis and the bladder.

•The rectorectal space (presacral space) lies between the rectum and sacrum.

—A double-layered peritoneal septum descends from the rectovesical (or rectouterine) pouch to the perineum.

•In males, this rectovesical septum separates the rectum from the seminal glands and prostate. Its lower part is often referred to as the rectoprostatic fascia.

•In females, the rectovaginal septum separates the rectum from the vagina.

Fig. 14.13 Peritoneal and subperitoneal spaces in the pelvis

Midsagittal section, viewed from the left side. Subperitoneal spaces shown in green. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

14.6 Neurovasculature of the Pelvis and

Perineum

Arteries of the Pelvis and Perineum

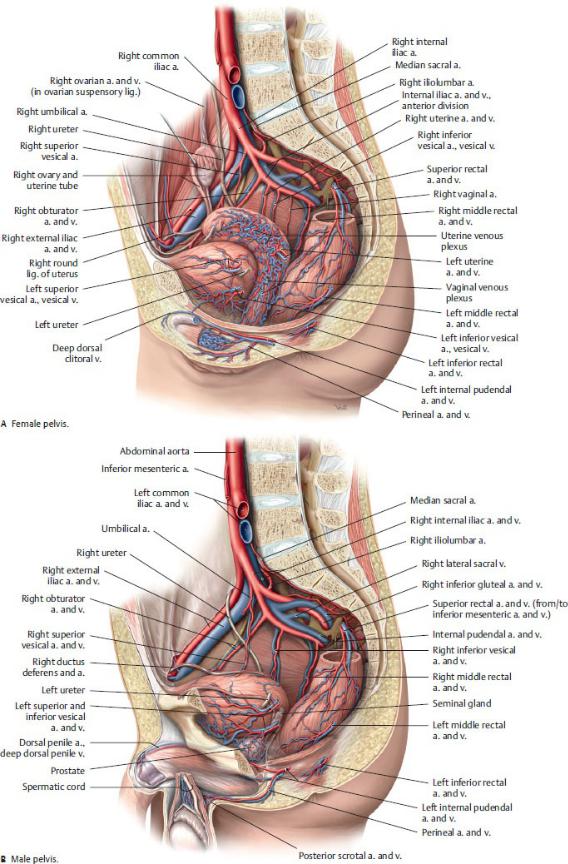

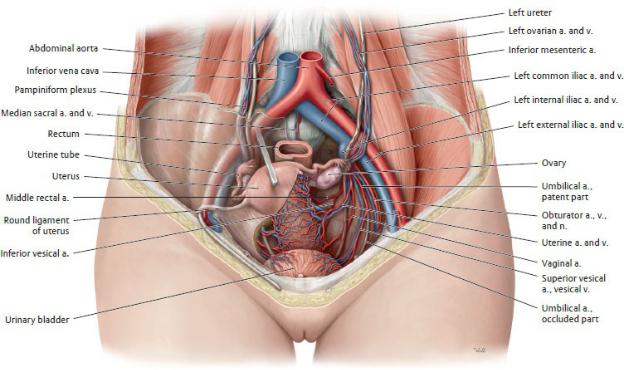

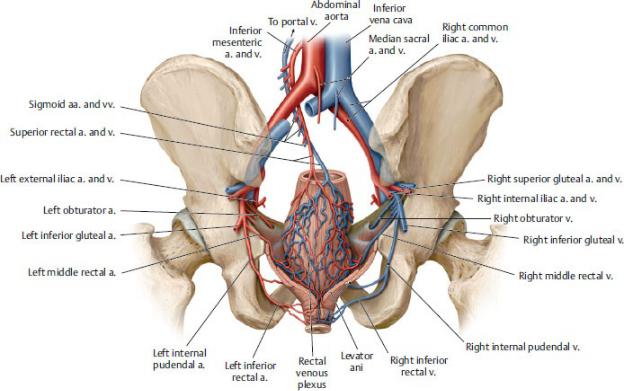

Pelvic viscera are well vascularized, primarily by branches of the internal iliac artery, with abundant ipsilateral and contralateral communications (Fig. 14.14).

—The right and left common iliac arteries descend along the pelvic brim before bifurcating into the external and internal iliac arteries at the level of the L5–S1 intervertebral disk.

—Each external iliac artery continues along the pelvic brim, lateral to the accompanying vein, and enters the lower limb without contributing branches to pelvic viscera.

—Each internal iliac artery descends into the lesser pelvis along the lateral wall before branching into two divisions ( Table 14.3)

1.The anterior division supplies most of the pelvic viscera, structures of the perineum, and some muscles in the gluteal region and thigh.

2.The posterior division contributes only parietal branches that supply muscles of the posterior abdominal wall, lower back, and gluteal region, as well as spinal branches that supply the meninges of the sacral spinal roots.

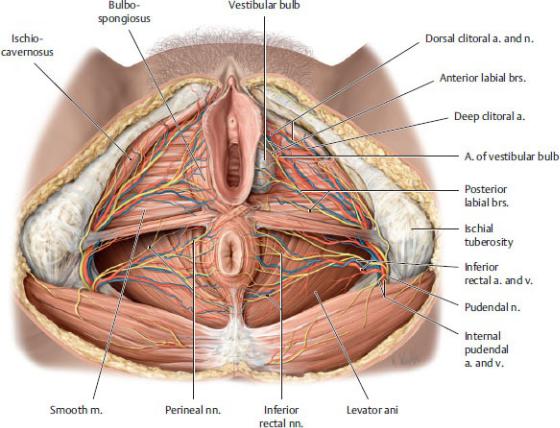

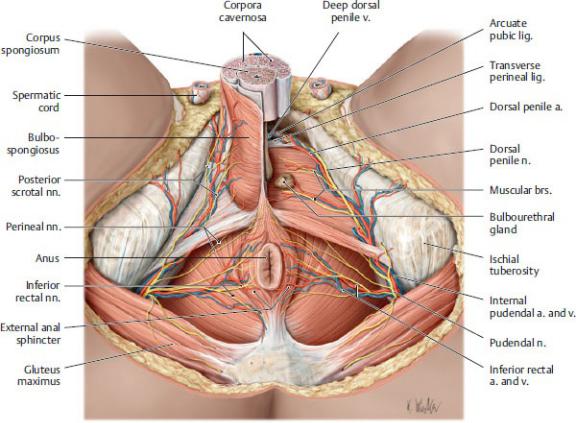

—The internal pudendal artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery, supplies most structures in the perineum. It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen and then passes through the lesser sciatic foramen into the perineum where it runs along the lateral wall of the anal triangle to the perineal membrane. Its major branches (Figs. 14.15 and 14.16) include the following:

Table 14.3 Branches of the Internal Iliac Artery |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

Anterior Division |

Posterior Division |

|||

Visceral branches |

Parietal branches |

Parietal branches |

|||

• |

Umbilical—superior |

• |

Obturator |

• |

Iliolumbar |

|

vesical* |

• |

Inferior gluteal |

• |

Lateral sacral |

• |

Uterine (female) |

|

|

• |

Superior gluteal |

•Vaginal (female)

•Inferior vesical (male)

•Middle rectal

•Internal pudendal

*After birth, the distal portion of the umbilical artery obliterates, but its remnant remains as the medial umbilical ligament on the anterior abdominal wall; the proximal portion remains as the superior vesical artery to the bladder.

•The inferior rectal artery, which supplies the external anal sphincter and skin around the anus

•The perineal artery, which supplies the structures of the superficial perineal pouch through posterior scrotal or posterior labial branches

•The dorsal penile or clitoral artery, which supplies structures in the deep perineal pouch and the glans of the penis or clitoris

—The external pudendal artery, a branch of the femoral artery in the thigh, supplies superficial tissues of the perineum.

Arteries of the pelvis that arise directly or indirectly from the abdominal aorta provide an important additional collateral blood supply to pelvic viscera.

—The ovarian and testicular arteries arise from the abdominal aorta at L2 and descend along the posterior abdominal wall.

•The ovarian artery crosses the pelvic brim and enters the pelvis within the suspensory ligament of the ovary. In the pelvis it supplies the ovary and uterine tube and anastomoses with the uterine artery (Fig. 14.17).

•The testicular artery passes through the inguinal canal as part of the spermatic cord to supply the testis. It does not supply any structures within the pelvis (Fig 14.18).

—The superior rectal artery, a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery, supplies the upper rectum and anal canal and anastomoses with middle and inferior rectal arteries in the pelvis and perineum (Fig. 14.19).

Veins of the Pelvis and Perineum

Blood from most pelvic viscera drains to a venous plexus contained either within the visceral fascia surrounding the organ (bladder, prostate) or within the organ wall (rectum).

—The visceral venous plexuses in the pelvis communicate freely, and most drain to the inferior vena caval system through tributaries of the internal iliac veins that accompany the arteries of similar name and vascular territory (area supplied by a vessel) (see Fig. 14.14).

—The internal pudendal vein accompanies the internal pudendal artery and drains most structures of the perineum. However, erectile tissues in the urogenital triangle drain through deep dorsal veins that pass under the pubic symphysis to join with visceral venous plexuses in the pelvis.

Fig. 14.14 Blood vessels of the pelvis

Idealized right hemipelvis, left lateral view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.15 Neurovasculature of the female perineum

Lithotomy position. Removed: left bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.16 Neurovasculature of the male perineum

Lithotomy position. Removed from left side: Perineal membrane, bulbospongiosus muscle, and root of penis. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.17 Blood vessels of the female genitalia

Anterior view. Removed from left side: Peritoneum. Displaced: Uterus. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 2. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.18 Blood vessels of the male genitalia

Anterior view. Opened: Inguinal canal and coverings of the spermatic cord. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 2. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.19 Blood vessels of the rectum

Posterior view. The main blood supply to the rectum is from the superior rectal artery; the middle rectal arteries serve as an anastomosis between the superior and inferior rectal arteries. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 2. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The internal iliac veins ascend from the pelvis to join with the external iliac veins. These join to form the right and left common iliac veins, which converge to form the inferior vena cava at the L5 vertebral level.

—There are three alternate venous drainages from pelvic viscera:

1.Ovarian veins drain directly into the inferior vena cava on the right and into the renal vein on the left, but they also communicate with other pelvic venous plexuses (uterine, vaginal), which drain to the internal iliac veins (see Fig. 14.17).

2.The superior rectal vein drains to the hepatic portal system through the inferior mesenteric vein. This drainage establishes an anastomosis between the portal and caval venous systems (a portosystemic anastomosis) with the middle and inferior rectal veins, which are tributaries of the internal iliac veins (see Figs. 14.19).

3.The vertebral venous plexus, which drains into the azygos system, communicates with pelvic visceral plexuses through tributaries of the internal iliac veins (see Fig. 3.17).

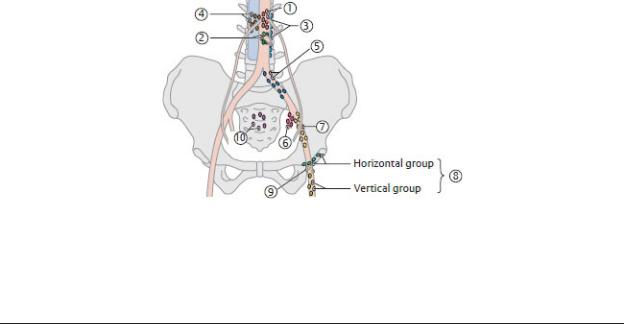

Lymphatics of the Pelvis and Perineum

Lymph from the pelvis and perineum travels through one or more groups of lymph nodes, all of which ultimately drain into the thoracic duct ( Table 14.4). The groups of nodes tend to be interconnected but vary in size and number.

There are several general drainage patterns.

—Within the pelvis, lymph drainage usually follows venous pathways, although structures that drain to the external iliac nodes do not follow this pattern.

—External iliac nodes receive lymph from the superior parts of the anterior pelvic viscera.

—Internal iliac nodes receive lymph from deep pelvic and deep perineal structures.

—Sacral nodes receive lymph from deep posterior pelvic viscera.

—Superficial and deep inguinal nodes drain most structures of the perineum.

—Inguinal nodes drain to external iliac nodes.

—External iliac, internal iliac, and sacral nodes drain to common iliac nodes, which in turn drain to lateral aortic nodes and lumbar trunks.

Nerves of the Pelvis and Perineum

Nerves of the pelvis and perineum include branches from somatic nerve plexuses as well as autonomic plexuses. Somatic nerves arise from the lumbar and sacral plexuses.

—The lumbar plexus (T12–L4) forms on the posterior abdominal wall (see Fig. 11.26). Its nerves primarily innervate muscles and skin of the lower abdominal wall and lower limb. However, its ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves transmit sensation from the mons pubis and labia and anterior scrotum in the perineum.

•The obturator nerve (L2–L4), passes along the sidewall of the pelvis and exits through the obturator canal. Although it does not innervate structures of the pelvis, its location is noteworthy because it can be injured during pelvic surgery.

—The sacral plexus forms on the posterior wall of the pelvis from the anterior rami of L4–S4. Except for short branches to pelvic floor muscles, branches of the plexus exit the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, where they innervate structures in the perineum, gluteal region, and lower limb (see

Section 15.4). Its branches in the pelvis include

Table 14.4 Lymph Nodes of the Pelvis

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Preaortic l.n. |

Superior mesenteric l.n. |

|

Inferior mesenteric l.n. |

Left lateral aortic l.n. |

|

Right lateral aortic (caval) l.n. |

|

Common iliac l.n. |

|

Internal iliac l.n. |

|

External iliac l.n. |

|

Superficial inguinal l.n. |

Horizontal group |

|

Vertical group |

|

|

Deep inguinal l.n. |

|

Sacral l.n. |

|

Abbreviation: l.n., lymph nodes |

|

|

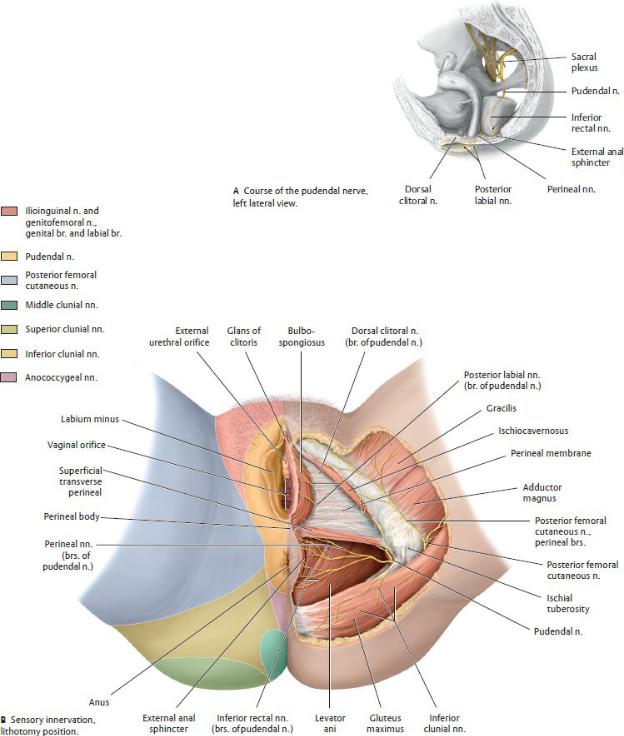

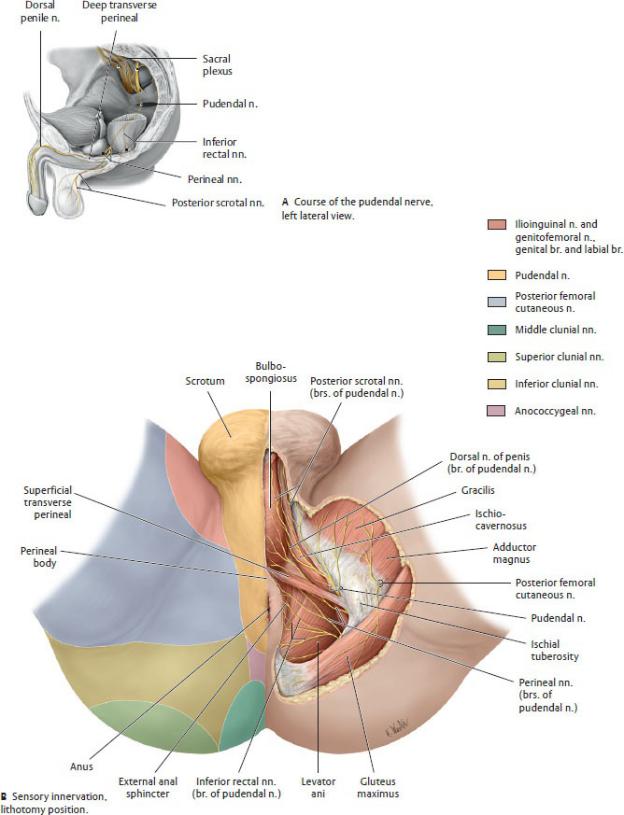

|

•The pudendal nerve (S2–S4), a branch of the sacral plexus, is the primary nerve of the perineum. It passes through the greater sciatic

foramen close to the ischial spine and then into the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen, where it courses anteriorly with the internal pudendal vessels. The pudendal nerve is a mixed somatic nerve (motor and sensory) but also carries postganglionic sympathetic fibers to perineal structures. Its major branches include the following (Figs. 14.20 and 14.21):

◦The inferior rectal nerve, which innervates the external anal sphincter

◦The perineal nerve, which supplies cutaneous branches to the scrotum and labia and motor branches to the muscles of the deep and superficial perineal pouches

◦The dorsal penile (clitoral) nerve, which is the primary sensory nerve to the penis and clitoris, especially to the glans.

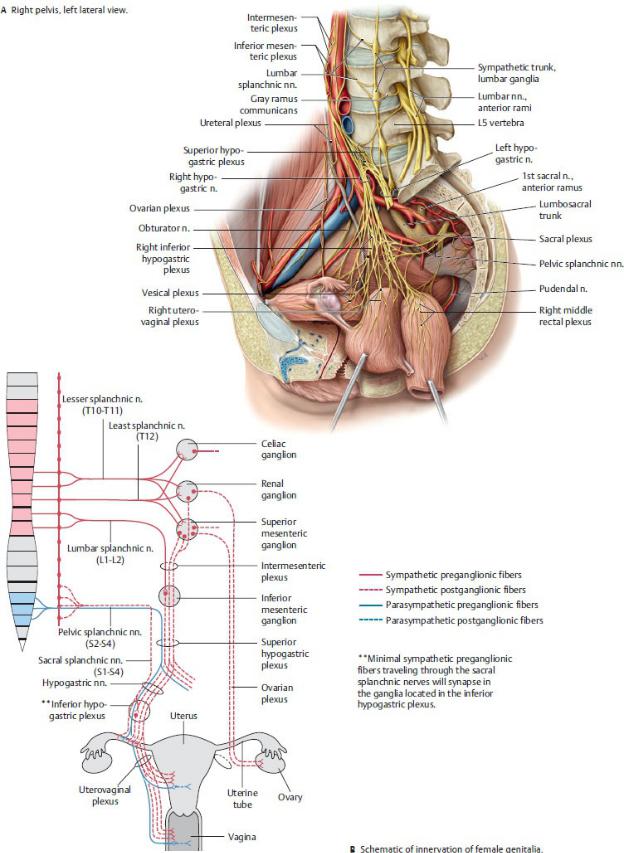

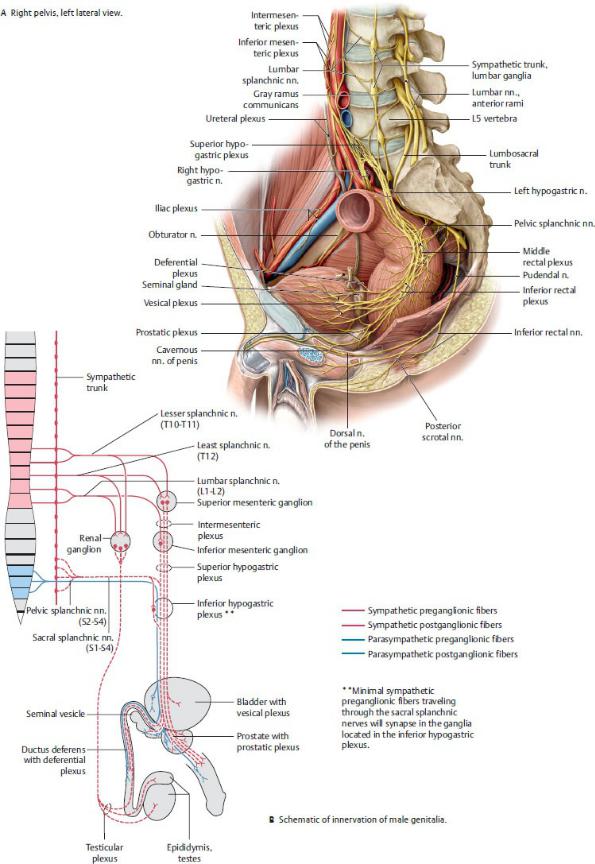

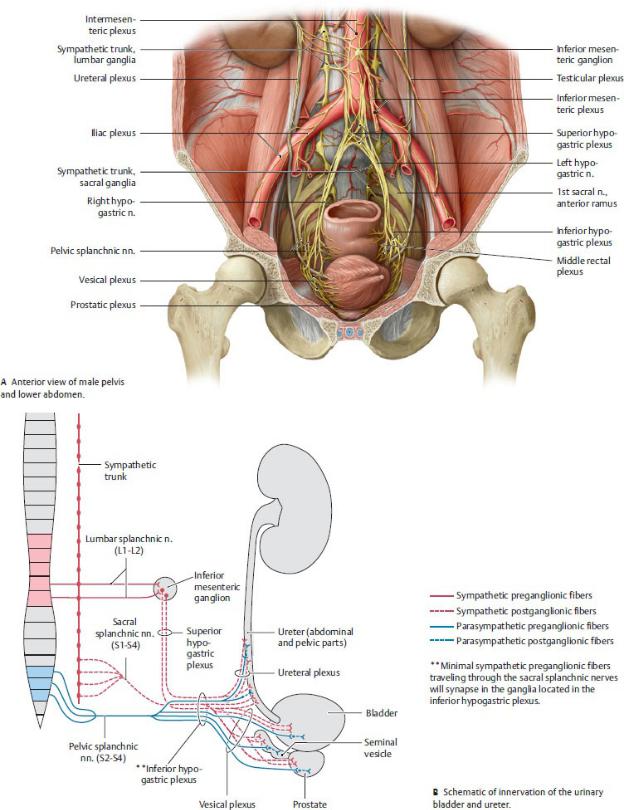

Autonomic innervation of the pelvis includes both sympathetic and parasympathetic contributions (Figs. 14.22, 14.23, 14.24, 14.25; see also Table 11.8).

—Sacral sympathetic trunks, the continuations of the lumbar sympathetic trunks, descend along the anterior surface of the sacrum to the coccyx, where they merge to form a small ganglion, the ganglion impar. The primary function of this part of the sympathetic trunks is to provide postganglionic sympathetic fibers via sacral splanchnic nerves to lower limb branches of the sacral plexus. It contributes a few fibers to the visceral plexuses of the pelvis.

—The superior hypogastric plexus, a continuation of the intermesenteric plexus in the abdomen, receives additional contributions from the two lower lumbar splanchnic nerves (sympathetic). It drapes over the bifurcation of the aorta and branches into right and left hypogastric nerves, which pass into the pelvis.

—Pelvic splanchnic nerves are the pelvic component of the parasympathetic nervous system. They originate from the sacral spinal cord and enter the pelvis with the S2–S4 anterior rami.

—The hypogastric nerves, joined by sacral splanchnic nerves (sympathetic) nerves and pelvic splanchnic nerves (parasympathetic), form right and left inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexuses.

—Rectal, uterovaginal (in females), prostatic (in males), and vesical plexuses are derived from the inferior hypogastric plexus and surround individual pelvic organs.

•Cavernous nerves arising from the prostatic plexus pass through the genital hiatus carrying parasympathetic nerves to perineal structures.

They are responsible for engorgement of the erectile tissue and erection of the penis and clitoris. They are particularly at risk during surgical removal of the prostate.

—Visceral sensory fibers from most structures in the pelvis travel with sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves, depending on the relationship of the viscera to the peritoneum, a division known as the “pelvic pain line.”

•From pelvic viscera in contact with the peritoneum, sensory fibers travel with sympathetic nerves to the superior hypogastric plexus and thoracic spinal cord.

•From pelvic viscera below the peritoneum, sensory fibers travel with parasympathetic pelvic splanchnic nerves to the sacral spinal cord.

•Although the rectum is in contact with the peritoneum on most of its surfaces, its visceral sensory fibers also travel with pelvic splanchnic nerves.

Fig. 14.20 Nerves of the female perineum and genitalia

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.21 Nerves of the male perineum and genitalia

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.22 Innervation of the anal sphincter mechanism

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 14.3: CLINICAL CORRELATION

PUDENDAL NERVE BLOCK

During labor, anesthesia of the pudendal nerve can ease perineal pain of delivery. A pudendal block can be administered through the posterior wall of the vagina, with the surgeon aiming the needle toward the ischial spine. The block can also be administered externally, inserting the needle through the skin medial to the ischial tuberosity. Since the pudendal nerve innervates only the perineum, the superior

vagina and cervix are not affected by the block, and the mother continues to feel the uterine contractions.

BOX 14.4: CLINICAL CORRELATION

PAIN TRANSMISSION DURING LABOR AND DELIVERY

The sensation of pain travels along both visceral sensory and somatic sensory routes during labor and delivery. The dividing line between these routes is the pelvic pain line, which refers to the relation of pelvic viscera to the peritoneum. Pain from the body and fundus of the uterus (intraperitoneal) travel along sympathetic nerves to the superior hypogastric plexus, and pain from the cervix and upper two-thirds of the vagina (subperitoneal) along parasympathetic nerves to the sacral spinal cord. Pain from superficial structures, the lower vagina and perineum, travels via branches of the pudendal nerve to the sacral plexus.

Fig. 14.23 Innervation of the female pelvis

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.24 Innervation of the female pelvis

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 14.25 Innervation of the pelvic urinary organs

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)