- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •1 Introduction to Anatomic Systems and Terminology

- •2 Clinical Imaging Basics Introduction

- •3 Back

- •4 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Spine

- •5 Overview of the Thorax

- •6 Thoracic Wall

- •7 Mediastinum

- •8 Pulmonary Cavities

- •9 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Thorax

- •10 The Abdominal Wall and Inguinal Region

- •12 Abdominal Viscera

- •13 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Abdomen

- •14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

- •15 Pelvic Viscera

- •16 The Perineum

- •18 Overview of the Upper Limb

- •19 Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb

- •20 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Upper Limb

- •21 Overview of the Lower Limb

- •22 Functional Anatomy of the Lower Limb

- •23 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Lower Limb

- •24 Overview of the Head and Neck

- •25 The Neck

- •26 Meninges, Brain, and Cranial Nerves

- •29 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Head and Neck

- •Index

24 Overview of the Head and Neck

The head and neck region contains the brain, cranial meninges, cranial nerves, and sensory organs, as well as components of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and endocrine systems. The skull encloses the brain, provides the bony framework for soft tissues of the head, and contains the nasal and oral cavities and bony orbits. The head and neck communicate with the thorax through the superior thoracic aperture and with the upper limb through the cervicoaxillary canal.

24.1 Bones of the Head: The Skull

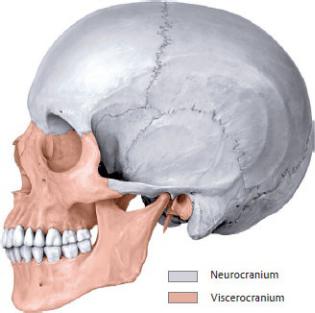

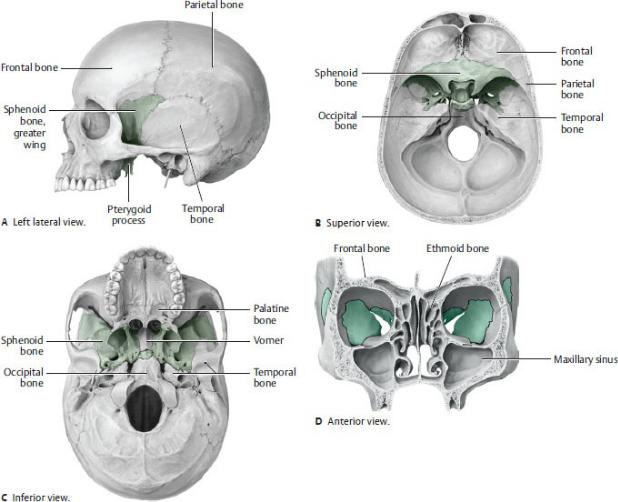

The skull is made up of two parts: the large neurocranium and the smaller viscerocranium (Fig. 24.1 and Table 24.1).

—The neurocranium, which makes up the largest part of the skull, houses and protects the brain.

—The viscerocranium includes the lower jaw and the thinwalled bones of the facial skeleton.

The Neurocranium

The neurocranium is formed by eight bones: the frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones, and paired parietal and temporal bones.

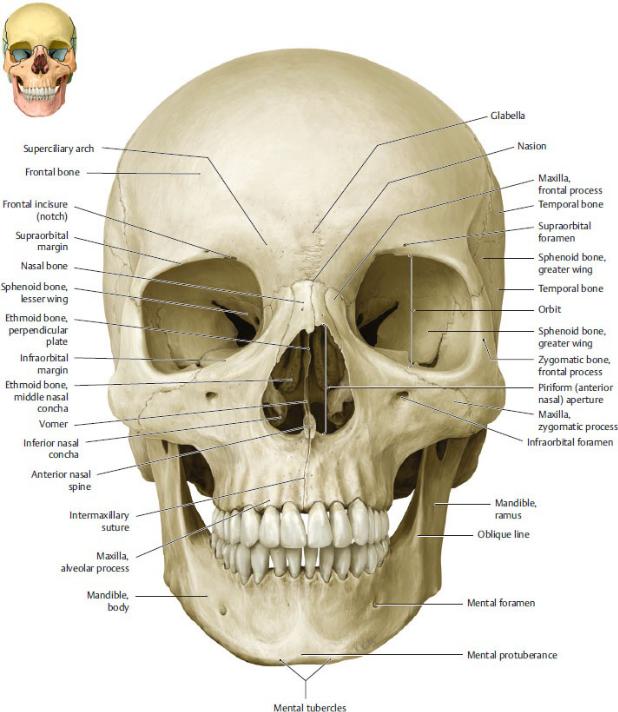

—The frontal bone (Figs. 24.2 and 24.3) forms the forehead, the roof, and the superior rim of the orbit (eye socket), and the floor of the anterior cranial fossa.

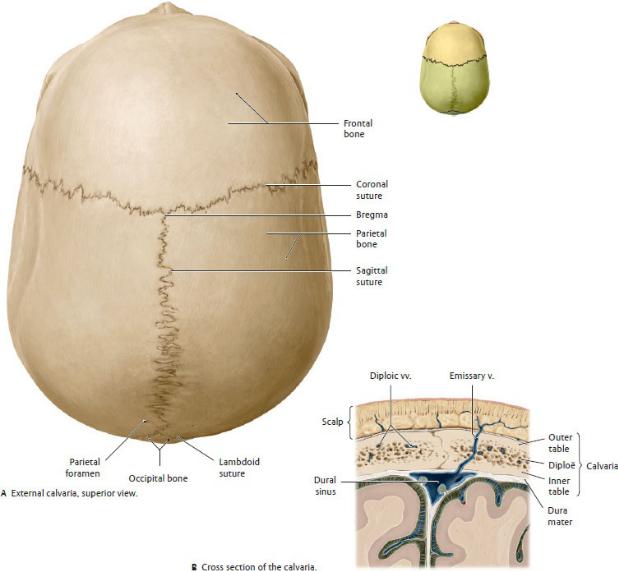

—The paired parietal bones (see Figs. 24.2, 24.5, 24.6) are flat bones that form the superolateral parts of the calvaria. Their internal surface has grooves for the middle meningeal arteries and the superior sagittal sinus.

Fig. 24.1 Bones of the neurocranium and viscerocranium

Left lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Table 24.1 Bones of the Neurocranium and Viscerocranium

Neurocranium |

Viscerocranium |

|||

• |

Frontal bone |

• |

Nasal bone |

|

• Sphenoid bone (excluding the |

• |

Lacrimal bone |

||

• |

pterygoid processes) |

• |

Ethmoid |

bone (excluding the |

Temporal bone (squamous |

• |

cribriform plate) |

||

• |

part, petrous part) |

Sphenoid |

bone (pterygoid |

|

Parietal bone |

|

processes) |

||

• |

Occipital bone |

• |

Maxilla |

|

• Ethmoid bone (cribriform plate) |

• |

Zygomatic bone |

||

• |

Auditory ossicles |

• |

Temporal bone (tympanic part, |

|

|

|

• |

styloid process) |

|

|

|

Mandible • Vomer |

||

|

|

• |

Inferior nasal concha |

|

|

|

• |

Palatine bone |

|

|

|

• |

Hyoid bone |

|

Most of the ethmoid bone is in the viscerocranium; most of the sphenoid bone is in the neurocranium. The temporal bone is divided between the two (see Fig. 24.1).

Fig. 24.2 Lateral skull

Left lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.3 Anterior skull

Anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

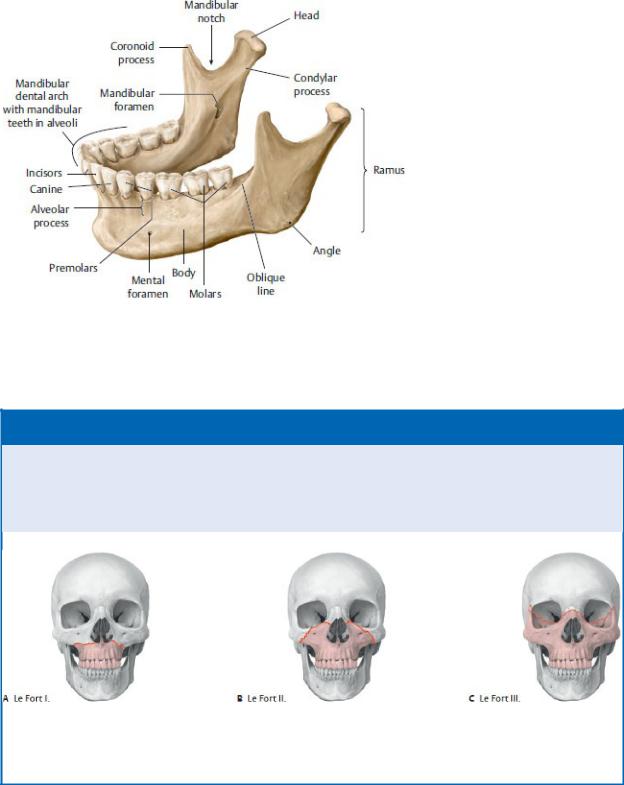

Fig. 24.4 Mandible

Oblique, left lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 24.1: CLINICAL CORRELATION

FRACTURES OF THE FACE

The framelike construction of the facial skeleton leads to characteristic patterns for fracture lines (classified as Le Fort I, II, and III fractures).

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

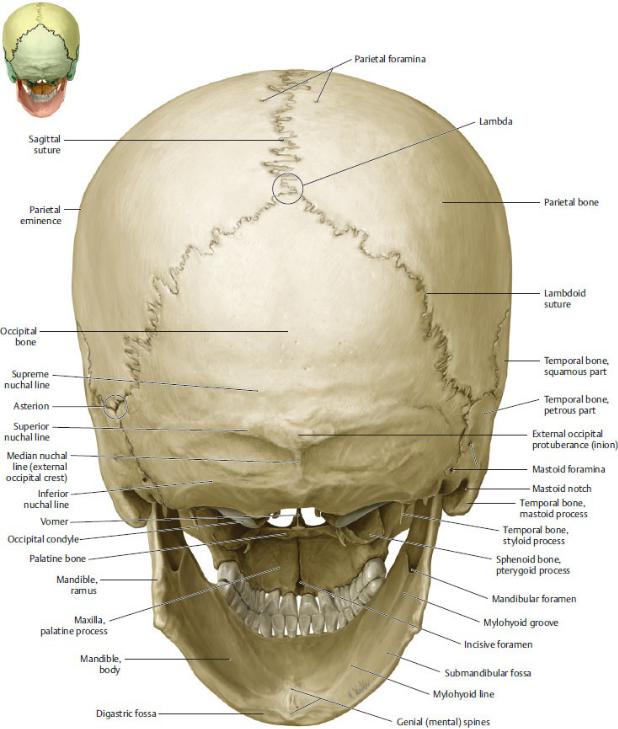

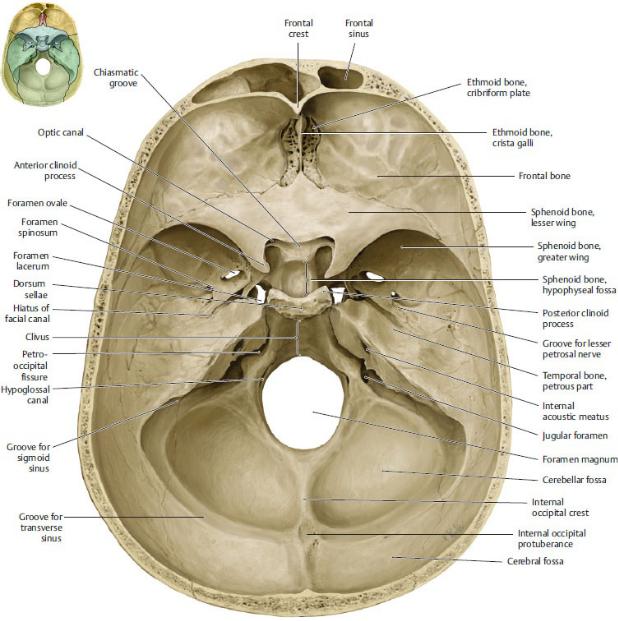

—The occipital bone (Figs. 24.6, 24.7, 24.8) forms the posterior cranial fossa of the skull base.

•A small anterior portion is called the clivus.

•Foramina (openings) include the large foramen magnum and the condylar canals. The jugular foramen is formed partly by the occipital bone and partly by the petrous part of the temporal bone.

•Inferiorly, occipital condyles articulate with the first cervical vertebra.

•The internal surface has grooves for the sigmoid and transverse dural sinuses.

•The external surface is marked with superior and inferior nuchal lines and an external occipital protuberance.

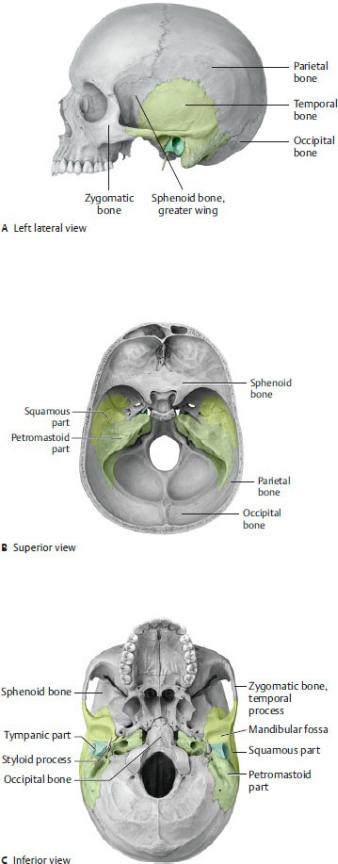

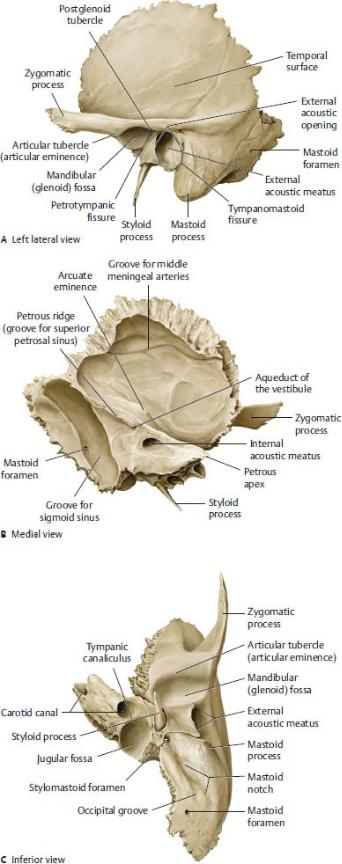

—The paired temporal bones (Figs. 24.2, 24.7, 24.8, 24.9, 24.10) form part of the middle and posterior cranial fossae.

•An outer squamous part forms the lateral skull, an inner petrous part encloses the middle and inner ear (neurocranium), and a tympanic part encloses the external auditory canal and tympanic membrane (viscerocranium).

•Processes include a mastoid process composed of a mesh of mastoid air cells, the posterior part of the zygomatic arch, and a long, pointed styloid process.

•Foramina (openings) include an internal acoustic meatus, external acoustic meatus, carotid canal, and stylomastoid foramen.

•A mandibular fossa and articular tubercle articulate with the mandible.

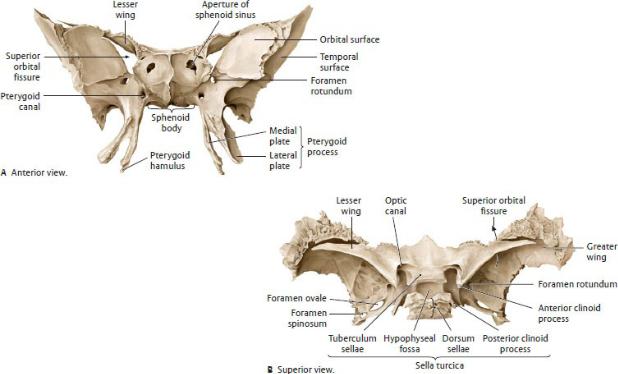

—The sphenoid bone (Figs. 24.11 and 24.12) forms the posterior part of the orbit and the floor and the lateral wall of the middle cranial fossa between the frontal and temporal bones.

•It has two greater wings that form parts of the middle cranial fossa and lateral walls of the skull.

•Two lesser wings form the posterior part of the anterior cranial fossa and end in anterior clinoid processes.

•The sphenoid body encloses the sphenoid sinus.

•A midline saddle-shaped formation, the sella turcica, contains the hypophyseal fossa and is limited anteriorly by the tuberculum sellae and posteriorly by the dorsum sellae and its posterior clinoid processes.

•Paired pterygoid processes, each with a medial and a lateral pterygoid plate, project inferiorly (viscerocranium).

•Paired openings include the optic canal, superior orbital fissure, foramen rotundum, foramen ovale, and foramen spinosum.

Fig. 24.5 Calvaria

The bones of the calvaria—the frontal, occipital, and two parietal bones—are composed of three layers: a dense outer table, a thin inner table, and a middle diploë layer. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.6 Posterior skull

Posterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.7 Base of the skull: exterior

Inferior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.8 Base of the skull: Interior

Superior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.9 Temporal bone in situ

Squamous part (light green), petromastoid part (pale green), tympanic part (dark green). (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.10 Temporal bone

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.11 Sphenoid bone in situ

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.12 Sphenoid bone

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

The Viscerocranium

The viscerocraniun, or facial skeleton, is composed of 15 bones: the ethmoid, mandible, and vomer, and the paired inferior nasal concha, maxillary, nasal, lacrimal, zygomatic, and palatine bones (see Figs. 24.2, 24.3, 24.15).

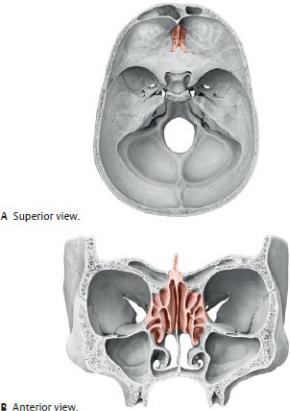

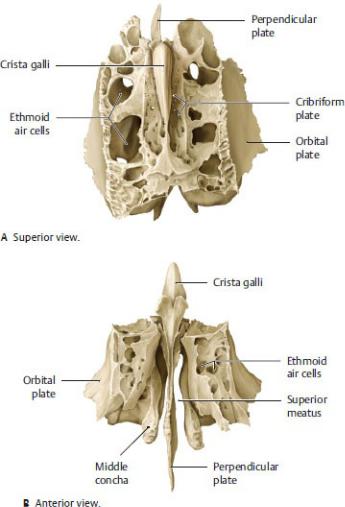

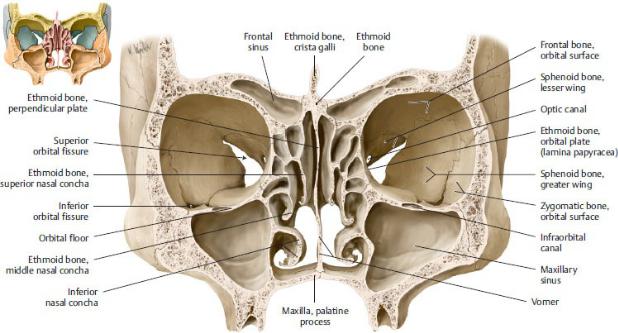

—The ethmoid bone (Figs. 24.13 and 24.14) forms part of the anterior cranial fossa, the medial walls of the orbits, and parts of the nasal septum and lateral nasal walls.

•The cribriform plate (neurocranium) sits in the anterior cranial fossa above the nasal cavity.

•The perpendicular plate forms part of the nasal septum.

•Ethmoid processes include the crista galli superiorly and superior and middle nasal concha inferiorly on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity.

•Numerous thin-walled ethmoid air cells form the ethmoid sinuses.

—Paired maxillary bones (maxilla) (Figs. 24.2, 24.3, 24.15) form the upper jaw, floors of the orbits, and parts of the nose and palate.

•The maxillary dental arch contains alveoli (sockets) for the upper teeth.

•Palatine processes form the anterior part of the palate, and frontal processes form part of the external nose.

•An infraorbital foramen opens onto the face.

•A large maxillary sinus within the maxilla sits below each orbit.

—The mandible (Figs. 24.2 and 24.4) forms the lower jaw.

•A horizontal body connects posteriorly with a vertical ramus on each side.

Fig. 24.13 Ethmoid bone in situ

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•An angle forms on each side at the junction between the body and the ramus.

•The superior end of each ramus has an anterior coronoid process that is separated from the posterior condylar process by a mandibular notch.

•The head of the condylar process articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone.

•Foramina include a mental foramen externally and a mandibular

foramen internally.

•The mandibular dental arch contains alveoli that house the lower teeth.

—Paired nasal bones (Fig. 24.3) form the bridge of the nose.

—Paired lacrimal bones (Fig. 24.2) form the anterior medial walls of the orbits and contain fossae for the lacrimal sacs.

—Paired zygomatic bones (Fig. 24.2) form the bony prominences of the cheeks, anterior parts of the zygomatic arches, and lateral walls of the orbits.

—Paired palatine bones (Fig. 24.7) have vertical parts that form the posterior lateral walls of the nasal cavity and horizontal processes that form the posterior parts of the palate.

—The vomer (Fig. 24.15) forms the inferior and posterior part of nasal septum.

—Paired inferior nasal conchae (Fig. 24.15) form the lowest scroll-like processes on the lateral walls of the nasal cavity.

Fig. 24.14 Ethmoid bone

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.15 Bones of the orbit and nasal cavities

Coronal section, anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Sutures of the Skull

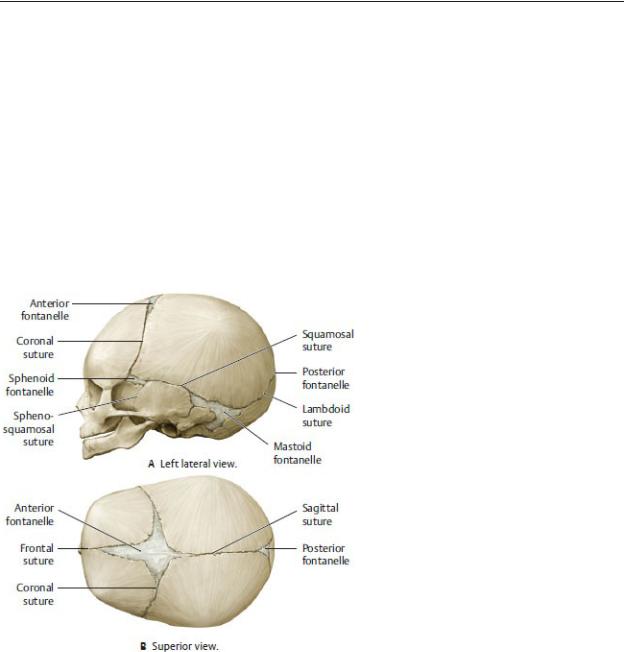

—During development, the bones of the calvaria grow outward from their center toward adjacent bones; the bones eventually fuse to form fibrous joints called sutures.

—Although there are many smaller sutures, the major sutures of the calvaria (see Figs. 24.2, 24.3, 24.5, 24.6) are

•the sagittal suture between the right and left parietal bones,

•the coronal suture between the frontal and parietal bones,

•the lambdoid suture between the occipital and parietal bones, and

•the squamous sutures between the parietal and temporal bones.

—At birth, growth of the skull bones and formation of the sutures are incomplete. Large fibrous areas, known as fontanelles, remain between the bones and allow for continued growth of the brain. The largest of these, the anterior fontanelle at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones, closes

between 18 and 24 months of age (Fig. 24.16).

BOX 24.2: DEVELOPMENTAL CORRELATION

CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS

Premature closure of the cranial sutures, a condition known as craniosynostosis, results in a variety of skull malformations, the shape of which depends on the suture involved. Plagiocephaly, the most common deformity, indicates premature closure of the coronal or lambdoid suture on one side and creates an asymmetrical appearance. Scaphocephaly is characterized by a long, narrow cranium produced by early closure of the sagittal suture. If untreated, craniosynostosis may lead to increased intracranial pressure, seizures, and delayed development of the skull and brain. Surgery is typically the recommended treatment to reduce the intracranial pressure and correct the deformities of the face and skull bones.

—Junctions of the sutures and other prominent points of the skull are useful for measuring growth of the skull and brain; determining race, gender, and age; and locating deep cranial structures (Table 24.2).

BOX 24.3: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SKULL FRACTURES AT THE PTERION

The thin bones that make up the pterion overlie the anterior branches of the middle meningeal artery, a branch of the maxillary artery that runs deep to the bone in the epidural space. Because of this relationship, skull fractures at the pterion can lead to a life-threatening epidural hemorrhage (see Box 26.3).

Table 24.2 Landmarks of the Skull

Landmark |

Location of Point or Area |

Nasion |

Junction of frontonasal and internasal sutures |

|

|

Glabella |

Most anterior prominence of frontal bone above |

|

the nasion |

Bregma |

Junction of coronal and sagittal sutures |

Pterion |

Area encompassing junction of frontal, parietal, |

|

sphenoid, and temporal bones along the |

|

sphenoparietal suture |

|

|

Vertex |

Most superior point of the skull along the sagittal |

|

suture |

|

|

Lambda |

Junction of lambdoid and sagittal sutures |

|

|

Asterion |

Junction of sutures joining occipital, temporal, and |

|

parietal bones |

|

|

(see Figs. 24.2, 24.3, 24.5, 24.6)

Fig. 24.16 The neonatal skull

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

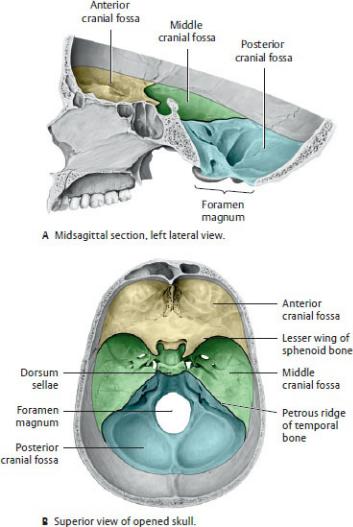

Cranial Fossae

—The floor of the cranial cavity is divided into three fossae, or spaces (Fig. 24.17; see also Fig. 24.8).

• The anterior cranial fossa, formed by the frontal and ethmoid bones

and lesser wing of the sphenoid bone, contains the frontal lobe of the brain and the olfactory bulbs (see Section 26.2 for a description of the brain).

•The middle cranial fossa, formed by the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid bone and squamous and petrous parts of the temporal bones, contains the temporal lobes of the brain, the optic chiasm, and the pituitary gland. The hypophyseal fossa separates the right and left halves of the middle cranial fossa.

•The posterior cranial fossa, formed primarily by the occipital bone and petrous parts of the temporal bones, contains the pons, medulla oblongata, and cerebellum of the brain. The medulla oblongata exits the skull through the foramen magnum located on the floor of the fossa, and grooves on the posterior and lateral walls accommodate the transverse and sigmoid dural venous sinuses.

Fig. 24.17 Cranial fossae

The interior of the skull base consists of three successive fossae that become progressively deeper in the frontal-to-occipital direction. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—Foramina within the anterior, middle, and posterior fossae allow blood vessels and nerves to pass through the skull (Fig. 24.18). (See Sections 24.3, 24.4 and 26.3 for arteries of the head, veins of the head, and cranial nerves, respectively.)

Fig. 24.18 Neurovascular structures entering or exiting the cranial cavity

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

24.2 Bones of the Neck

Most bones of the neck are parts of the vertebral column, thoracic skeleton, or pectoral girdle (see Fig. 1.5A).

—The seven cervical vertebrae support the head on the vertebral column and provide attachment for neck muscles.

—The manubrium of the sternum forms the inferior midline boundary of the anterior neck.

—The clavicles form the lateral boundaries of the neck.

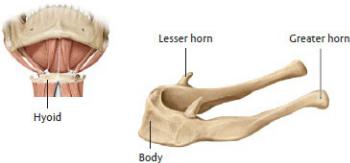

—The hyoid bone, a small U-shaped bone, lies anterior to the C3 vertebra in the neck (Fig. 24.19).

•It has a body and paired lesser and greater horns.

•The hyoid does not articulate directly with any other bones of the skeleton, but muscles and ligaments attach it to the mandible, styloid processes of the temporal bones, larynx, clavicles, sternum, and scapulae.

Fig. 24.19 Hyoid bone

The hyoid bone is suspended in the neck by muscles between the floor of the mouth and the larynx. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

24.3 Arteries of the Head and Neck

Arteries of the head and neck are branches of the right and left subclavian and common carotid arteries (see Fig. 5.6).

—The brachiocephalic trunk arises from the aortic arch and divides behind the right sternoclavicular joint to form the right subclavian and right common carotid arteries.

—The left subclavian and left common carotid arteries are direct branches of

the aortic arch in the superior mediastinum of the thorax.

The Subclavian Artery

The subclavian arteries enter the neck through the superior thoracic aperture and pass laterally between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. Two branches, the vertebral artery and the thyrocervical trunk, arise medial to the anterior scalene muscles on each side and supply structures in the head and neck (Fig. 24.20). Other branches supply structures at the base of the neck and thoracic outlet.

—The vertebral artery passes posteriorly in the neck to ascend through the transverse foramina of C1–C6 vertebrae and enters the foramen magnum at the base of the skull.

•In the neck, it contributes the single anterior spinal artery and paired posterior spinal arteries that supply the upper spinal cord.

•In the skull, it gives off the posteroinferior cerebellar arteries.

•It terminates by joining the contralateral vertebral artery to form a single basilar artery, which supplies the posterior circulation of the brain.

—The thyrocervical trunk is a short trunk that branches into four arteries:

•the inferior thyroid artery, the largest branch, which turns medially to supply the larynx, trachea, esophagus, and thyroid and parathyroid glands;

•the suprascapular and transverse cervical arteries, which supply muscles of the back and scapular region; and

•the ascending cervical artery, a small branch that supplies muscles in the neck.

—The costocervical trunk arises posteriorly from the subclavian artery and branches into

•the deep cervical artery, which supplies muscles of the posterior neck.

•the supreme intercostal artery, which supplies the muscles of the first intercostal space.

—The internal thoracic artery arises from the inferior side of the subclavian artery. It descends into the thorax on either side of the sternum to supply muscles of the thorax and sternum (see Section 5.2).

BOX 24.4: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SUBCLAVIAN STEAL SYNDROME

“Subclavian steal” usually results from a stenosis of the left subclavian artery located proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery. When the

left arm is exercised, there may be insufficient blood flow to the arm. As a result, blood is “stolen” from the vertebral artery circulation, causing a reversal of flow in the vertebral artery on the affected side. This leads to a deficient blood flow in the basilar artery and may deprive the brain of blood, producing a feeling of lightheadedness.

Subclavian steal syndrome

Red circle indicates area of stenosis; arrows indicate direction of blood flow. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.20 Arteries of the neck

The Carotid Artery System

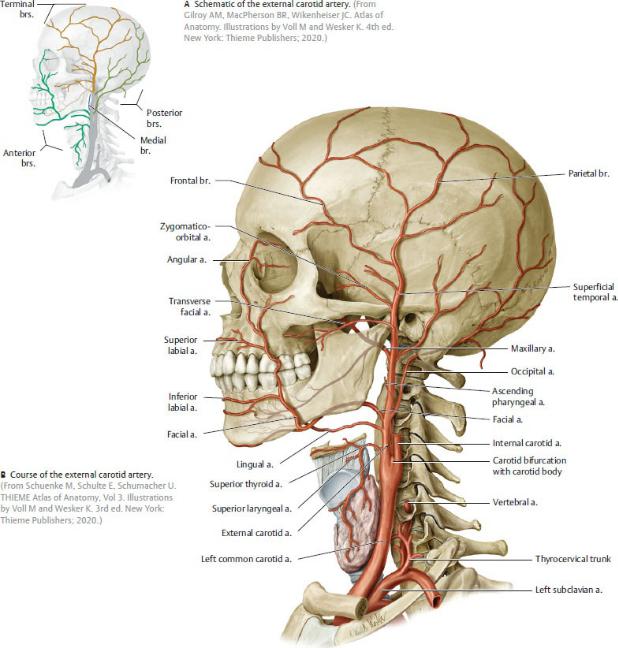

The carotid artery system supplies structures of the neck, face, skull, and brain and consists of paired common carotid, external carotid, and internal carotid arteries and their branches.

—The common carotid artery enters the neck from the thorax and ascends, with the internal jugular vein and vagus nerve, within a fascial sleeve, the carotid sheath.

•Its only branches, the external carotid and internal carotid arteries, arise from its bifurcation at the C4 vertebral level (Fig. 24.21).

Fig. 24.21 External carotid artery

Left lateral view.

—The external carotid artery supplies most structures of the face and head except the brain and the orbits. Six branches arise from the external carotid artery in the neck before it passes behind the mandible and finally bifurcates into two terminal branches, the maxillary and superficial temporal arteries (Table 24.3).

1. The superior thyroid artery supplies the thyroid gland and, through its

superior laryngeal artery, the larynx.

2.The lingual artery supplies the posterior tongue and floor of the mouth, parts of the oral cavity, the tonsil, soft palate, epiglottis, and sublingual gland.

3.The facial artery ascends deep to the submandibular gland, which it supplies, and crosses the mandible from below to enter the face. It passes lateral to the corners of the mouth and terminates near the medial angle of the eye as the angular artery. The branches of the facial artery include

◦the submental and tonsillar branches in the neck, and

◦the superior and infe rior labial arteries and a lateral nasal artery on the face.

4.The occipital artery supplies branches to the posterior neck muscles.

5.The ascending pharyngeal artery sends branches to the pharynx, ear, and deep neck muscles.

6.The posterior auricular artery passes posteriorly to supply the scalp behind the ear.

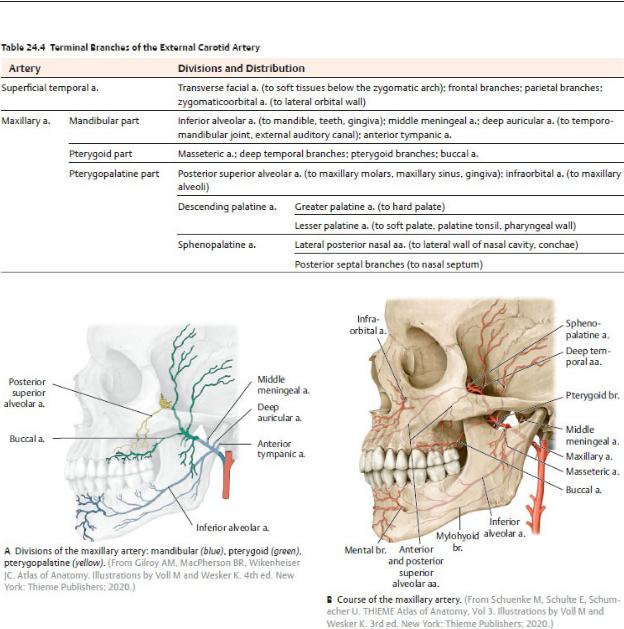

—The maxillary artery arises posterior to the mandible and passes medially through the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae (see Sections 27.5 and 27.6). Branches from its three parts, the mandibular, pterygoid, and pterygopalatine parts, supply most structures of the face (Table 24.4; Figs. 24.22 and 24.23).

—The superficial temporal artery passes superiorly through the temporal region anterior to the ear and terminates as frontal and parietal arteries on the scalp. Its branches on the face (Fig. 24.21; see Table 24.4) include the following:

• The transverse facial artery, which supplies the parotid gland and duct and crosses anteriorly to supply the skin of the face

• The zygomatico-orbital artery, which supplies the lateral orbit

• The middle temporal artery, which supplies the temporal region

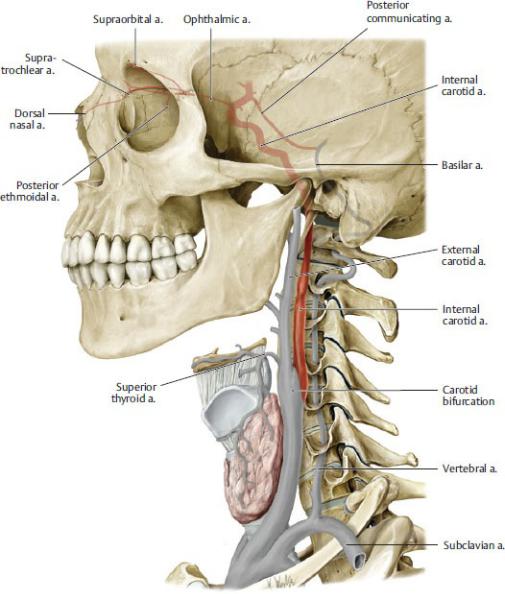

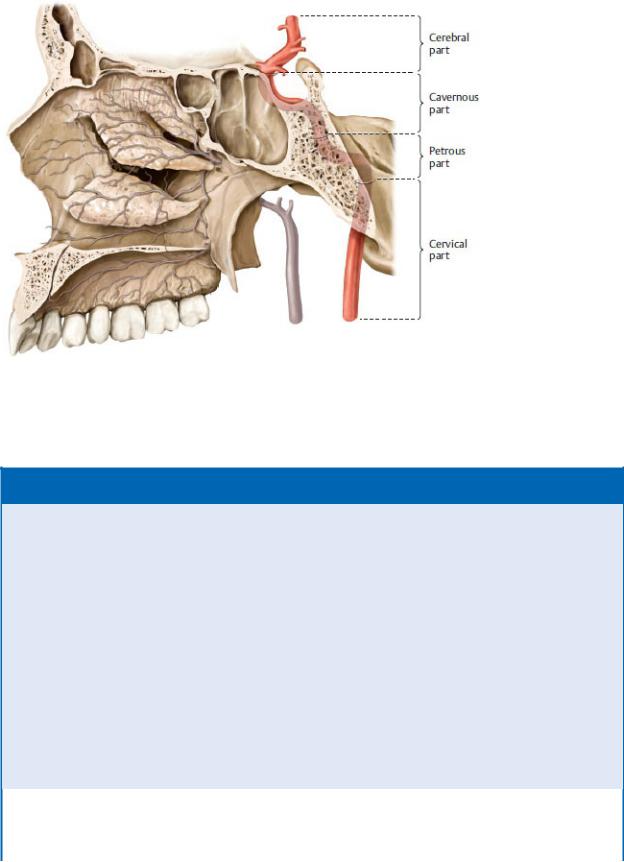

—The internal carotid artery is the continuation of the common carotid artery (Figs. 24.24 and 24.25).

• It is described in four parts:

◦A cervical part in the neck that has no branches

◦A petrous part that courses within the carotid canal of the temporal bone

◦A cavernous part that passes through the cavernous sinus (a venous sinus lateral to the sella turcica; see Figs. 26.6 and 26.7)

◦A cerebral part that emerges into the middle cranial fossa posterior

to the orbit

•Two receptors are located within the internal carotid artery near its origin.

◦The carotid sinus, a baroreceptor that responds to changes in arterial pressure, is noticeable as a small dilation near the origin of the internal carotid artery.

◦The carotid body, a small mass of tissue located near the carotid sinus, is a chemoreceptor that monitors blood oxygen levels. Stimulation of the carotid body initiates an increase in heart rate, respiration rate, and blood pressure.

Table 24.3 Anterior, Medial, and Posterior Branches of the External Carotid Artery

Branch |

Artery |

Divisions and Distributions |

Anterior brs. |

Superior |

Glandular br. (to thyroid gland); superior |

|

thyroid a. |

laryngeal a.; sternocleidomastoid br. |

|

|

|

|

Lingual a. |

Dorsal lingual brs. (to base of tongue, |

|

|

palatoglossal arch, tonsil, soft palate, |

|

|

epiglottis); sublingual a. (to sublingual |

|

|

gland, tongue, oral floor, oral cavity); deep |

|

|

lingual a. |

|

|

|

|

Facial a. |

Ascending palatine a. (to pharyngeal wall, |

|

|

soft palate, pharyngotympanic tube); |

|

|

tonsillar branch (to palatine tonsils); |

|

|

submental a. (to oral floor, submandibular |

|

|

gland); labial aa.; angular a. (to nasal root) |

|

|

|

Medial br. |

Ascending |

Pharyngeal brs.; inferior tympanic a. (to |

|

pharyngeal |

mucosa of inner ear); posterior meningeal |

|

a. |

a. |

|

|

|

Posterior |

Occipital a. |

Occipital brs.; descending br. (to posterior |

brs. |

|

neck muscles) |

|

|

|

|

Posterior |

Stylomastoid a. (to facial n. in facial |

|

auricular a. |

canal); posterior tympanic a.; auricular br.; |

|

|

occipital br.; parotid br. |

Note: For terminal brs, see Table 24.4.

Fig. 24.22 Maxillary artery

Left lateral view.

Fig. 24.23 Deep branches of the maxillary artery

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•The ophthalmic artery, which arises within the skull as the first major branch of the internal carotid artery, passes through the optic canal to supply the orbital contents, including the retina of the eye through its central retinal artery.

◦Branches of the ophthalmic artery, the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries to the anterior scalp and ethmoidal arteries to the nasal cavity, anastomose with branches of the external carotid artery (Box 24.5).

•The anterior and middle cerebral arteries arise from the internal carotid artery to supply the anterior circulation of the brain (see Section 26.2).

Fig. 24.24 Internal carotid artery

Left lateral view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.25 Course of the internal carotid artery in the skull

Right side, medial view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 24.5: CLINICAL CORRELATION

ANASTOMOSES BETWEEN EXTERNAL CAROTID AND INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERIES

The external carotid artery supplies superficial and deep regions of the face, the nasal and oral cavities, and the neck, while the internal carotid artery supplies the brain and the orbit. There are areas of overlap and important anastomoses between these circulations that can become clinically significant, such as the collateralization of blood supply to the brain, the transmission of infections from the face to the cerebral circulation, and accurate ligation of the source of a nosebleed. Primary areas of anastomoses include branches of the facial artery and ophthalmic arteries in the orbit and the sphenopalatine and ethmoidal arteries on the nasal septum.

Anastomoses between branches of the external carotid and internal carotid arteries

Branches of the external carotid artery are grouped by color: anterior = red; medial = blue; posterior = green; terminal = brown. Branches of the external carotid artery (e.g. the facial artery, red) communicate with terminal branches of the internal carotid artery (e.g. the ophthalmic artery, purple). (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

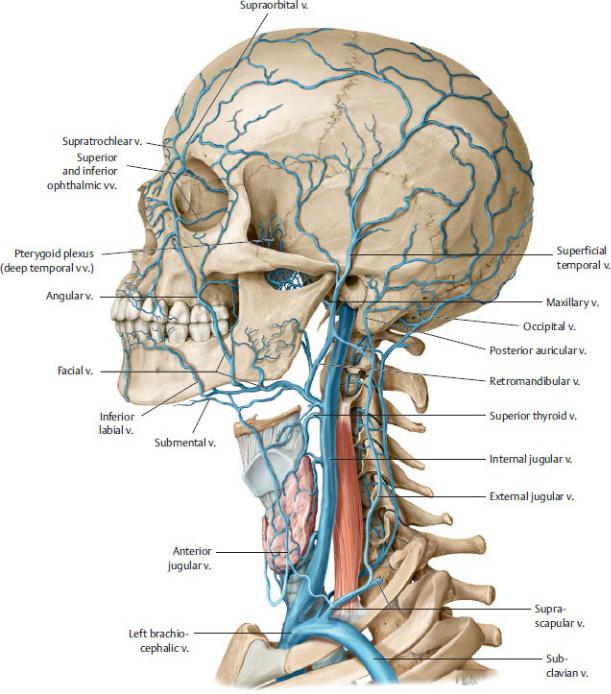

24.4 Veins of the Head and Neck

—Superficial and deep veins of the head and neck drain almost exclusively to the external and internal jugular veins, although some also communicate with the vertebral venous plexus of the vertebral column (Figs. 24.26 and

24.27).

—Superficial veins generally follow the course of the arteries, but the veins are usually more numerous, more variable, and more interconnected than the arteries.

—The most prominent superficial veins on each side of the head include

•the supratrochlear and supraorbital veins, which drain to the angular vein;

•the angular vein, which joins with the deep facial vein and continues inferiorly as the facial vein;

•the pterygoid venous plexus, which drains areas supplied by the maxillary artery, including the orbit, nasal cavity, and oral cavity (it drains to the maxillary and deep facial veins);

•the deep facial vein which arises from the pterygoid venous plexus and drains to the facial vein;

•the facial vein, which drains to the internal jugular vein;

•the superficial temporal and maxillary veins, which join to form the retromandibular vein;

•the retromandibular vein, which joins the posterior auricular vein to form the external jugular vein; and

•the occipital vein, which drains to the external jugular vein.

—Right and left external jugular veins form posterior to the angle of the mandible by the union of the posterior auricular veins and the posterior division of the retromandibular veins.

•They cross the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the neck and drain into the subclavian vein.

•They drain the scalp and side of the face.

•Their tributaries include the retromandibular, posterior auricular, occipital, transverse cervical, suprascapular, and anterior jugular veins.

—A right and left internal jugular vein forms at the jugular foramen at the skull base and descends within the carotid sheath with the common carotid artery and vagus nerve.

•It joins the subclavian vein in the root of the neck to form the brachiocephalic vein. The junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins is called the jugulosubclavian junction, or venous angle. The thoracic duct and right lymphatic duct terminate at this junction, respectively.

•It drains the brain, the anterior face and scalp, and the viscera and deep muscles of the neck.

Fig. 24.26 Superficial veins of the head and neck

Left lateral view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•Its tributaries include the dural venous sinuses, facial vein, lingual vein, pharyngeal veins, and superior and middle thyroid veins.

—A small anterior jugular vein originates from superficial veins on each side near the hyoid bone.

•It descends to the base of the neck and terminates in the external jugular or subclavian vein.

•A jugular venous arch may connect the right and left anterior jugular veins at the base of the neck, above the sternum.

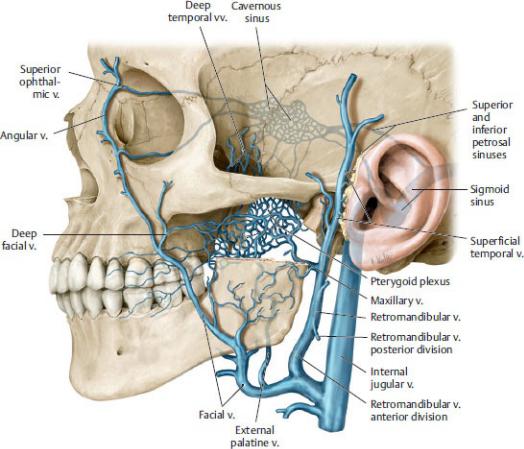

—Deep veins of the orbit and brain drain to dural venous sinuses, venous channels formed within the outer covering of the brain that have no arterial counterpart (see Section 18.1). Dural venous sinuses drain eventually to the internal jugular vein.

Fig. 24.27 Deep veins of the head

Left lateral view. The pterygoid plexus is a venous network situated between the mandibular ramus and the muscles of mastication. The cavernous sinus connects branches of the facial vein to the sigmoid sinuses. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

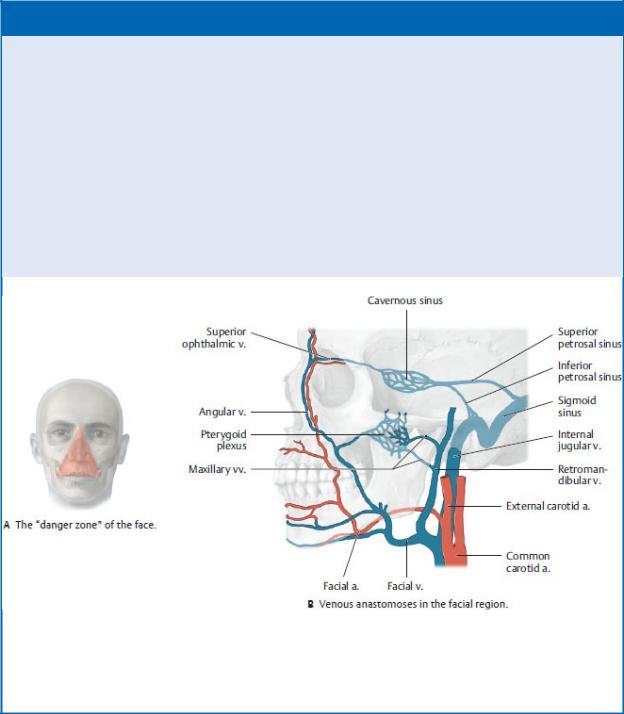

BOX 24.6: CLINICAL CORRELATION

VENOUS ANASTOMOSES AS PORTALS OF INFECTION

The extensive anastomoses between superficial veins of the face, and the deep veins of the head (e.g., pterygoid plexus) and dural sinuses (e.g., cavernous sinus) is clinically very important. Veins in the triangular danger zone of the face are, in general, valveless. Thus, bacterial infections from the face are easily disseminated into the cranial cavity. An infection on the lip, for example, may travel via the facial vein to the cavernous sinus, resulting in a cavernous sinus thrombosis (infection leading to clot formation that may occlude the sinus) or even meningitis.

The “danger zone” and venous anastomoses in the facial region

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

24.5 Lymphatic Drainage of the Head and Neck

—Superficial lymph nodes of the head and neck extend along the external jugular vein.

• They receive lymph from local areas and drain to the deep cervical

nodes.

•Superficial node groups include occipital, retroauricular, mastoid, parotid, anterior cervical, and lateral cervical nodes (Fig. 24.28; Table 24.5).

Table 24.5 Superficial Cervical Lymph Nodes

Lymph Node (l.n.) |

Drainage Region |

Retroauricular l.n. |

Occiput |

|

|

Occipital l.n. |

|

|

|

Mastoid l.n. |

|

|

|

Superficial parotid l.n. |

Parotid-auricular region |

|

|

Deep parotid l.n. |

|

|

|

Anterior superficial cervical l.n. |

Sternocleidomastoid region |

|

|

Lateral superficial cervical l.n. |

|

|

|

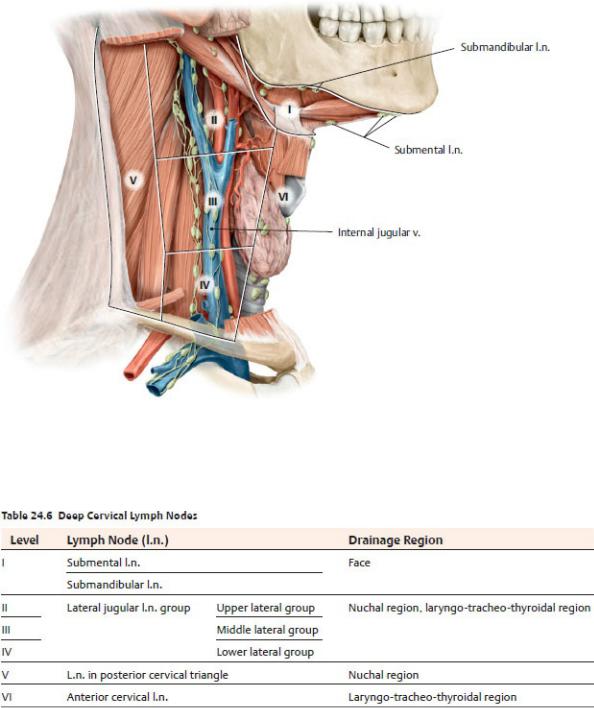

—Lymph from structures in the head and neck ultimately drains into deep cervical lymph nodes that lie along the internal jugular vein deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 24.29; Table 24.6). There are two groups of deep cervical nodes:

•Superior deep cervical nodes, known as the jugulodigastric group, lie near the facial and internal jugular veins and posterior belly of the digastric muscle. Submandibular and submental nodes also drain to this group. Superior deep cervical nodes drain either to the inferior deep cervical nodes or directly to the jugular lymphatic trunks.

•Inferior deep cervical nodes are usually associated with the lower internal jugular vein, but some nodes also reside in the area around the subclavian vein and brachial plexus. Inferior deep cervical nodes drain directly to the jugular lymphatic trunks.

—Lymphatic vessels from the deep cervical nodes join to form jugular lymphatic trunks.

•On the right, these trunks drain directly or indirectly (via the right lymphatic duct) into the right jugulosubclavian junction (right venous angle).

•On the left, these trunks join the thoracic duct, which drains into the left jugulosubclavian junction (left venous angle).

Fig. 24.28 Superficial cervical lymph nodes

Right lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 24.29 Deep cervical lymph nodes

Right lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 3. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

24.6 Nerves of the Head and Neck

Innervation of head and neck structures is a complex combination of somatic and autonomic nerves arising from the cervical spinal cord, cranial nerves, and the sympathetic trunk. A brief overview is provided here. For more detailed

discussions see Section 26.3 (cranial nerves), Section 26.4 (autonomic innervation), and Section 25.4 (nerves of the neck).

—Somatic nerves of the head and neck include the following:

•spinal nerves C1 through C4, which innervate structures in the head and neck

◦The cervical plexus is derived from anterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C1–C4.

◦The suboccipital, greater occipital, and third occipital nerves are derived from posterior rami of cervical spinal nerves.

•spinal nerves C5 through T1, whose anterior rami form the brachial plexus that innervates the upper limb (see Section 18.4)

•Cranial nerves (CN I to CN XII), which arise from the brain.

—Autonomic nerves of the head and neck include

•parasympathetic nerves, which arise in association with four of the cranial nerves (CN III, VII, XI, and X), and

•sympathetic nerves, which arise from the cervical sympathetic trunk.