- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •1 Introduction to Anatomic Systems and Terminology

- •2 Clinical Imaging Basics Introduction

- •3 Back

- •4 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Spine

- •5 Overview of the Thorax

- •6 Thoracic Wall

- •7 Mediastinum

- •8 Pulmonary Cavities

- •9 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Thorax

- •10 The Abdominal Wall and Inguinal Region

- •12 Abdominal Viscera

- •13 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Abdomen

- •14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

- •15 Pelvic Viscera

- •16 The Perineum

- •18 Overview of the Upper Limb

- •19 Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb

- •20 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Upper Limb

- •21 Overview of the Lower Limb

- •22 Functional Anatomy of the Lower Limb

- •23 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Lower Limb

- •24 Overview of the Head and Neck

- •25 The Neck

- •26 Meninges, Brain, and Cranial Nerves

- •29 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Head and Neck

- •Index

21 Overview of the Lower Limb

The lower limb supports the weight of the entire body and therefore is designed for strength and stability. Bones, muscles, and tendons tend to be more robust and joints more stable than those found in the upper limb.

21.1 General Features

—In the anatomic position, the body is upright and supported by the lower limb. The feet are together and pointed forward.

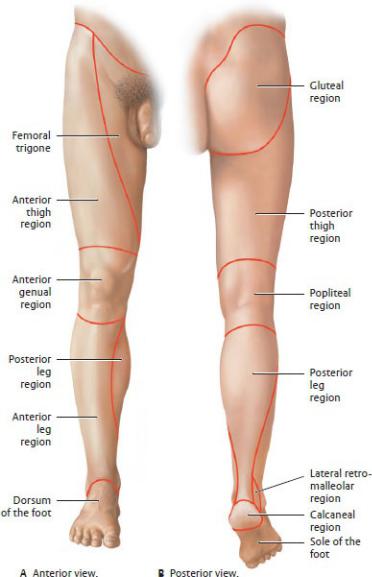

—The regions of the lower limb (Fig. 21.1) include

•the gluteal region, which includes the buttocks and lateral hip region and overlies the pelvic girdle;

Fig. 21.1 Regions of the lower limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•the thigh, between the hip and the knee;

•the popliteal and genual regions, at the knee;

•the leg, between the knee and ankle; and

•the foot, which has dorsal and plantar surfaces. The plantar surface is also called the sole of the foot.

—Movements of the joints of the lower limb are similar to movements of the upper limb, with some variations. They include

•flexion—plantar flexion indicates flexing the foot or toes downward;

•extension—dorsiflexion indicates extension of the foot, as when lifting the foot or toes upward;

•abduction and adduction—the axis for abduction and adduction of the toes is the 2nd digit;

•external rotation and internal rotation—movement around a longitudinal axis;

•inversion, or supination of the foot—lifting the medial edge of the sole; and

•eversion, or pronation of the foot lifting the lateral edge of the sole.

—As in the upper limb, muscles of the lower limb can be described as intrinsic or extrinsic:

•Intrinsic muscles of the foot originate and insert on bones of the foot and ankle.

•Extrinsic flexor and extensor muscles of the foot originate in the leg.

◦Synovial tendon sheaths surround the long flexor and extensor tendons as they cross the ankle joint.

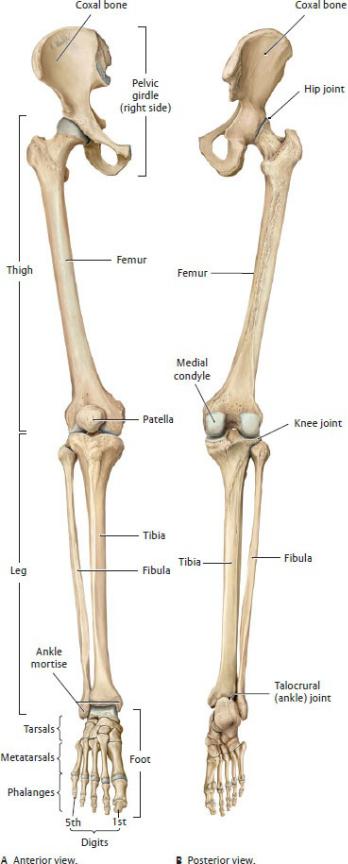

21.2 Bones of the Lower Limb

Bones of the lower limb include the hip (coxal) bone that articulates with the sacrum to form the pelvic girdle, the femur of the thigh, the tibia and fibula of the leg, the tarsal bones of the ankle and hindfoot, and the metatarsal bones and phalanges of the midfoot and forefoot (Fig. 21.2).

—The coxal (hip) bone forms the lateral part of the pelvic girdle. The features of the coxal bone are discussed in Section 10.2 with the bony pelvis.

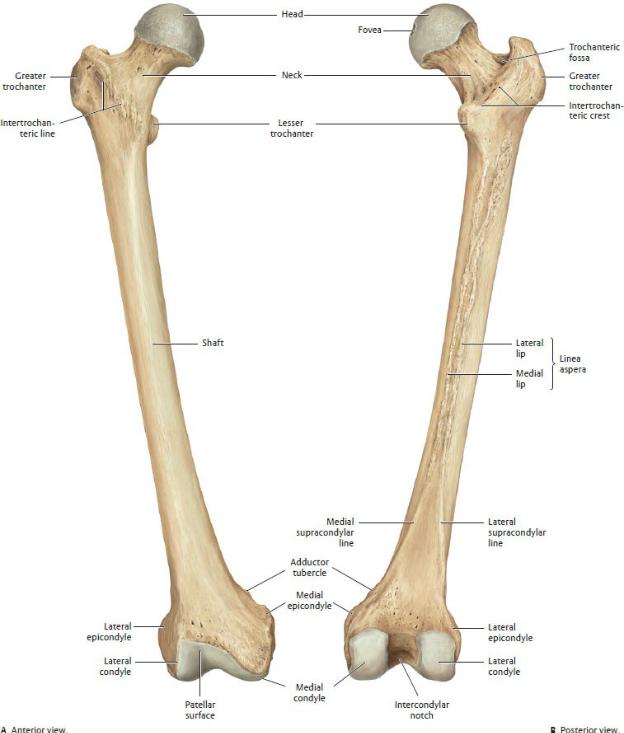

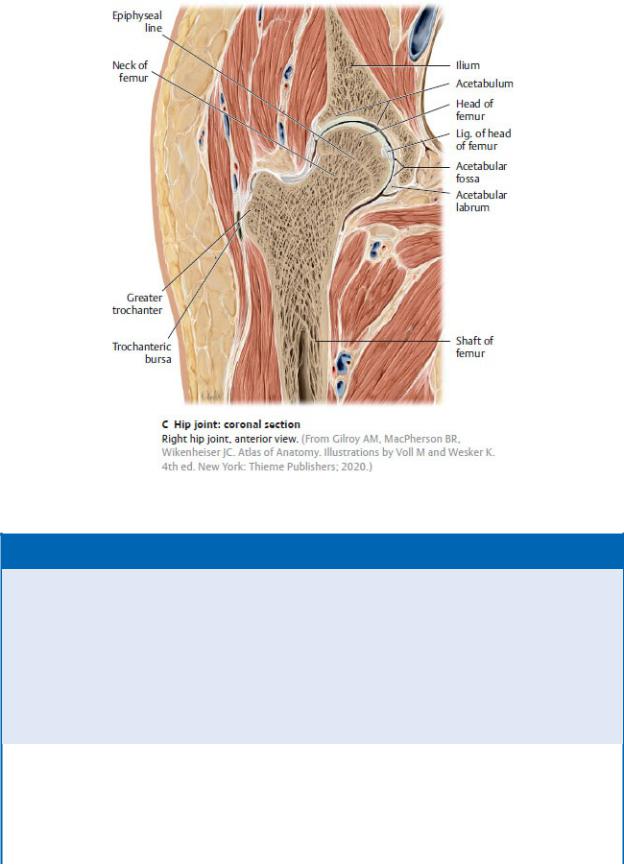

—The femur is the long bone of the thigh (Fig. 21.3).

•Proximally, its large ball-shaped head articulates with the acetabulum of the hip bone.

•The neck, angled inferolaterally, connects the head with the shaft.

•Greater and lesser trochanters, sites for muscle attachments, are separated by an intertrochanteric crest posteriorly and an intertrochanteric line anteriorly.

•The shaft is slightly bowed anteriorly and, in the anatomic position, is angled medially.

•Linea aspera, paired ridges on the posterior surface of the shaft, diverge distally as the medial and lateral supracondylar lines.

Fig. 21.2 Bones of the lower limb

Right limb. The skeleton of the lower limb consists of a limb girdle and an attached free limb. The free limb is divided into the thigh (femur), leg (tibia and fibula), and foot. It is connected to the pelvic girdle by the hip joint. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•Distally, the medial and lateral epicondyles are attachment sites for ligaments of the knee, and the adductor tubercle is an attachment site for muscle.

•The femur articulates with the tibia at the medial and lateral condyles, which are separated by the intercondylar notch.

•The femur articulates with the patella anteriorly at the patellar surface.

—The patella, a large sesamoid bone, forms the kneecap (Fig. 21.4; see also

Fig. 22.12).

•It articulates with the distal femur at the knee joint.

•Superiorly, its base is attached to the quadriceps tendon.

•Inferiorly, its apex is attached to the patellar ligament.

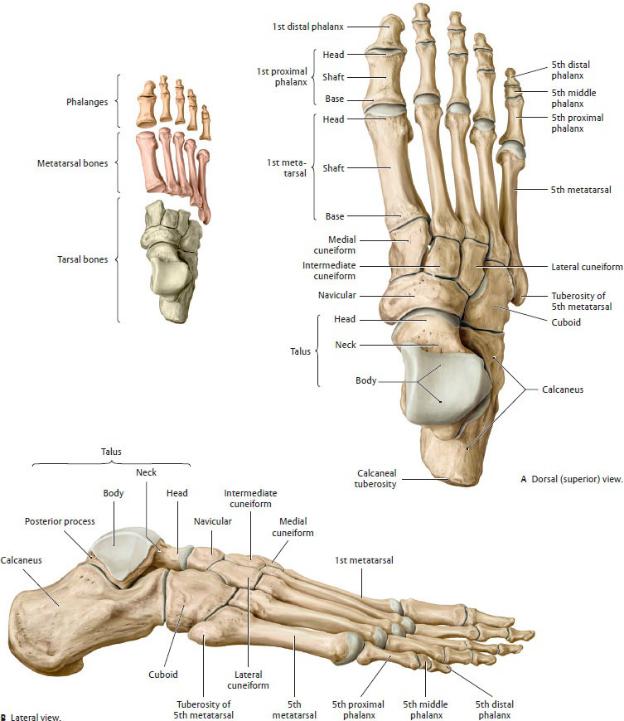

—The tibia is the large medial long bone of the leg (Fig. 21.5).

•Proximally, it articulates with the femur at the tibial plateau, which has flat medial and lateral condyles separated by an intercondylar eminence.

•It articulates with the fibula proximally at the tibiofibular joint and distally at the tibiofibular syndesmosis.

•A triangular anterolateral tubercle (Gerdy’s tubercle) separates the lateral condyle from the lateral surface of the tibial shaft.

•A tibial tuberosity on the anterior surface below the tibial plateau is an attachment site for anterior thigh muscles via the patellar ligament.

•Distally, the medial malleolus forms part of the mortise of the ankle joint.

•The sharp anterior border of the shaft is palpable between the knee and ankle.

•An interosseous membrane connects the shaft of the tibia and fibula.

—The fibula is the lateral bone of the leg (see Fig. 21.5).

•Proximally, the head articulates with the lateral condyle of the tibia at the proximal tibiofibular joint.

•A narrow neck connects the head to the shaft.

•A distal tibiofibular syndesmosis binds the fibula to the distal tibia.

•Distally, the lateral malleolus forms the lateral wall of the mortise of the ankle joint.

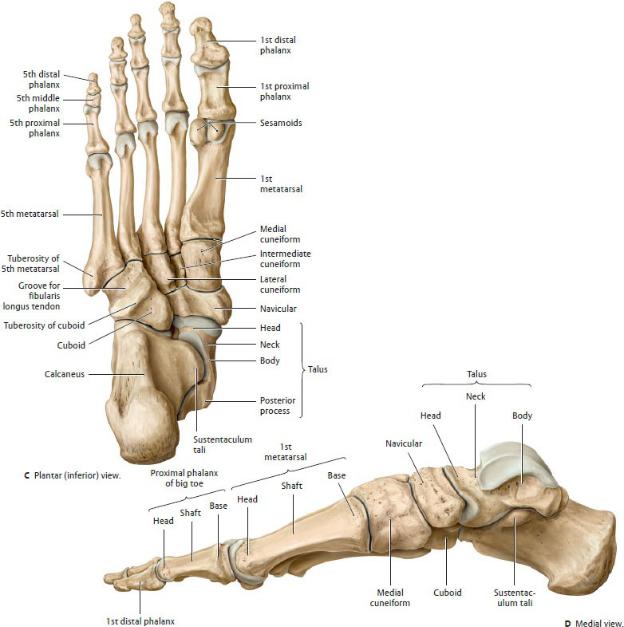

—The tarsal bones consist of seven short bones of the foot (Fig. 21.6).

•The talus is the most superior tarsal bone.

◦The body articulates with the tibia and fibula at the ankle joint.

◦The head, which articulates with the navicular bone, is the highest part of the medial arch of the foot.

◦The inferior surface articulates with the calcaneus.

•The calcaneus is the large tarsal bone of the heel.

◦It articulates superiorly with the talus and anteriorly with the cuboid.

◦The sustentaculum tali, a medial process, forms part of the medial arch of the foot.

•The navicular lies anterior to the talus and forms part of the medial arch.

•The cuboid lies anterior to the calcaneus on the lateral side of the foot.

•The medial, intermediate, and lateral cuneiform bones lie anterior to the navicular and articulate distally with the metatarsal bones.

Fig. 21.3 Right femur

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.3 (continued) Right femur

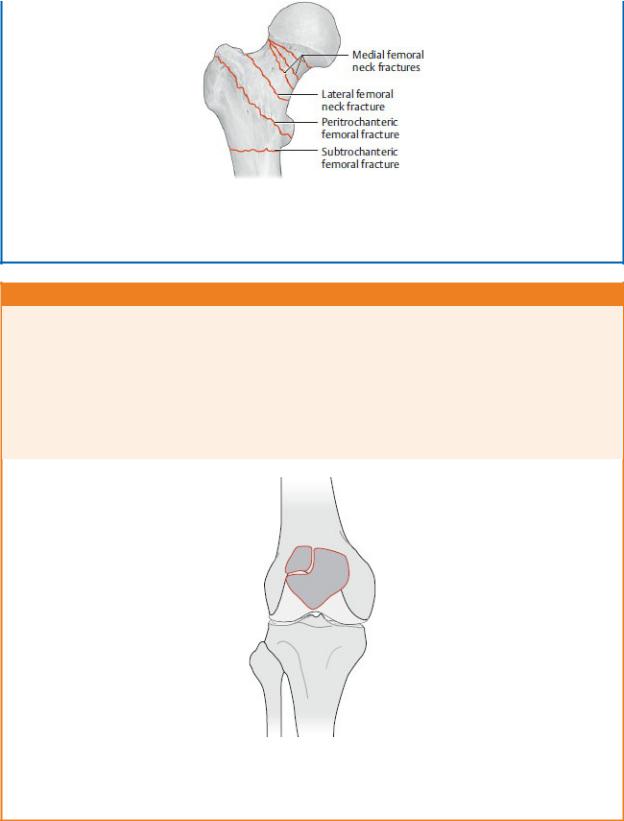

BOX 21.1: CLINICAL CORRELATION

FRACTURES OF THE FEMUR

Fractures of the femoral neck commonly occur following a lowenergy impact in women over 60 years of age with osteoporosis. The distal fragment of bone is pulled upward by the quadriceps femoris, adductor, and hamstring muscles, causing shortening and lateral (external) rotation of the limb. Femoral shaft fractures are less frequent and usually result from a major trauma.

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

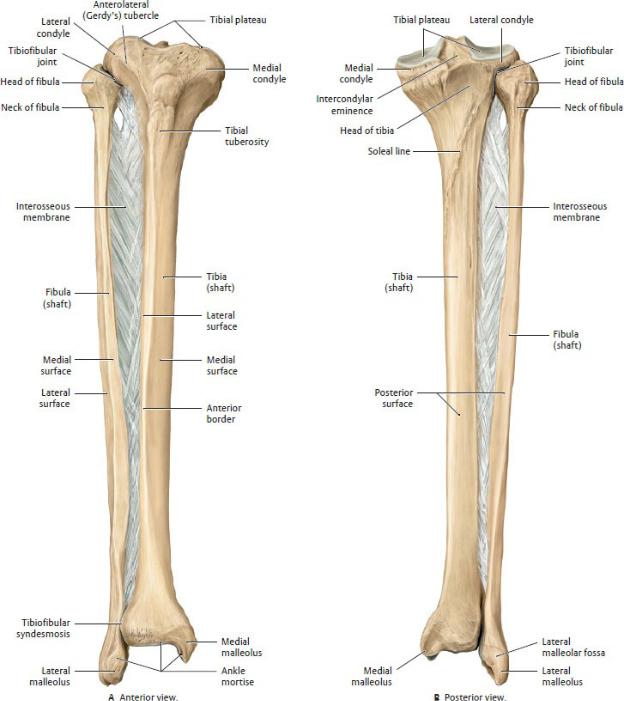

BOX 21.2: DEVELOPMENTAL CORRELATION

BIPARTITE PATELLA

Ossification of the patella occurs at ages 3 to 6 years, usually from several ossification centers. Occasionally, one center, most commonly the upper lateral segment, fails to fuse with the larger segment, resulting in a bipartite (two-part) patella. On imaging this may appear as a patellar fracture.

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.4 Patella

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.5 Tibia and fibula

Right leg. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.6 Bones of the right foot

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.6 (continued) Bones of the right foot

—The metatarsal bones consist of five long bones that are designated 1st (medial) through 5th (lateral).

•Proximally, their bases articulate with the tarsal bones.

•Distally, their heads articulate with the proximal phalanges.

•The shaft connects the heads and bases.

•Paired sesamoid bones are associated with the head of the 1st metatarsal.

•A prominent tuberosity at the base of the 5th metatarsal is a site of

attachment for muscles of the leg.

—The phalanges are small long bones of the toes.

•The 2nd through 5th digits have a proximal, middle, and distal phalanx.

•The 1st digit, the hallux, or great toe, has only a proximal and a distal phalanx.

21.3 Fascia and Compartments of the Lower

Limb

—Similar to the upper limb, the lower limb musculature is enclosed within a snug sleeve of deep fascia, which is continuous from the iliac crest to the sole of the foot but has regional designations.

•Fascia lata surrounds muscles of the thigh. Laterally, longitudinal fibers of the fascia lata form a tough band, the iliotibial tract, which extends from the iliac crest to the anterolateral (Gerdy’s) tubercle of the tibia (see Fig. 22.41).

•Crural fascia invests muscles of the leg, and at the ankle it forms the flexor and extensor retinacula.

•Fascia on the dorsum of the foot is thin, but on the sole it forms a thickened longitudinal band, the plantar aponeurosis.

•Digital fibrous sheaths are extensions of the plantar aponeurosis onto the toes, where they enclose the flexor tendons.

—The deep fascia creates compartments that separate the limb musculature. Muscles within each compartment are usually similar in function, innervation, and blood supply. Compartments of the lower limb (see Fig. 22.46) include the following:

•Anterior, medial, and posterior compartments of the thigh

•Anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior compartments of the leg (crural compartments)

•Medial, lateral, central, and interosseous compartments on the sole of the foot

•Dorsal compartment on the dorsum of the foot

21.4 Neurovasculature of the Lower Limb

Arteries of the Lower Limb

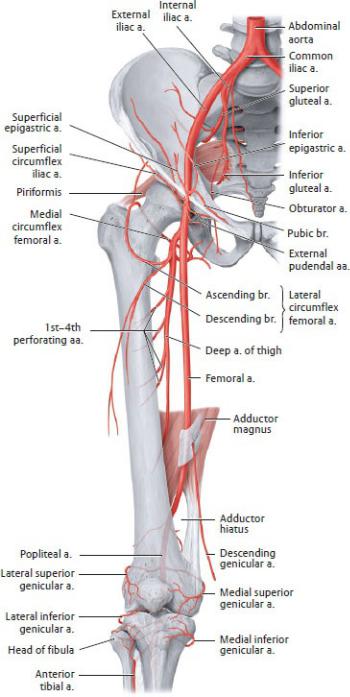

Branches of the internal iliac artery in the pelvis and the femoral artery (a continuation of the external iliac artery) supply blood to the lower limb (Fig.

21.7).

—The branches of the internal iliac artery that supply the lower limb include

•the superior gluteal and inferior gluteal arteries, which exit the pelvis posteriorly through the greater sciatic foramen to supply the gluteal region; and

•the obturator artery, which exits the pelvis anteriorly through the obturator foramen to supply the medial thigh.

—The femoral artery (clinically known as the superficial femoral artery) enters the anterior thigh deep to the inguinal ligament enclosed within a femoral sheath (formed by extensions of the deep fascia of the abdomen). The artery descends along the anteromedial thigh between the anterior and medial muscular compartments and ends at the adductor hiatus, a gap in the tendon of the adductor magnus muscle. Its branches include

•the superficial circumflex iliac and superficial epigastric arteries, which supply the abdominal wall;

•the superficial and deep external pudendal arteries, which supply the inguinal region;

•the descending genicular artery, which contributes to the anastomosis around the knee; and

•the deep artery of the thigh, which is the primary blood supply to the thigh.

—The deep artery of the thigh (deep femoral artery, profunda femoris), the largest branch of the femoral artery, arises in the proximal thigh. Its branches include

•the medial circumflex femoral artery, which is the primary blood supply to the hip joint;

•the lateral circumflex femoral artery, which supplies the hip joint and contributes to the anastomosis around the knee joint; and

Fig. 21.7 Course and branches of the femoral artery

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

• the 1st through 3rd (or 4th) perforating arteries, which supply

muscles of the anterior, medial, and posterior muscles of the thigh.

—A cruciate anastomosis provides a collateral blood supply to structures around the hip. Contributions to the anastomosis include

•the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries,

•the 1st perforating artery, and

•the inferior gluteal artery.

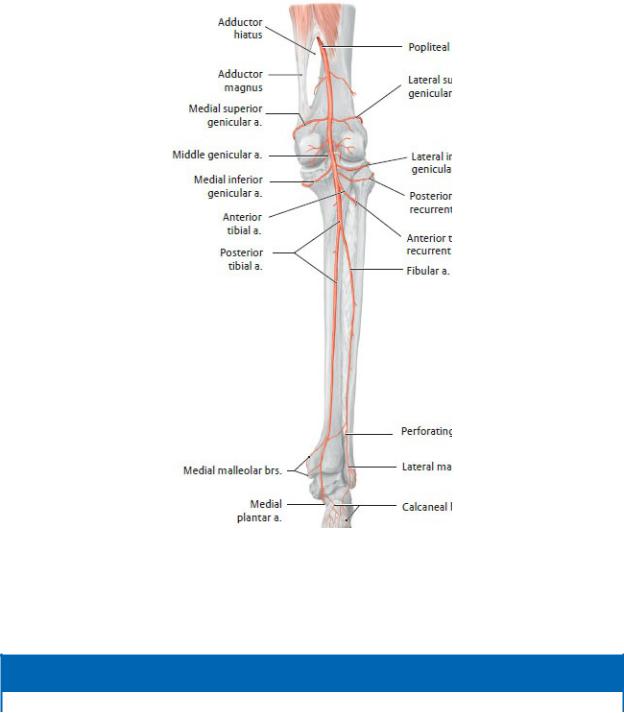

Fig. 21.8 Arteries of the knee and posterior leg

Right leg, posterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 21.3: CLINICAL CORRELATION

FEMORAL HEAD NECROSIS

Although the cruciate anastomosis surrounds the hip joint, only the medial circumflex femoral artery gives rise to branches that enter the capsule and supply the femoral head. These end arteries are at risk during the dislocation or fracture of the femoral neck. Tearing of these vessels will result in avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

—The popliteal artery is the continuation of the femoral artery as it enters the popliteal fossa, a cavity posterior to the knee joint (Fig. 21.8).

•Five genicular branches run medially and laterally around the knee.

•Anterior tibial and posterior tibial arteries, the terminal branches of the popliteal artery, arise in the proximal part of the posterior leg compartment.

—A genicular anastomosis that supplies the knee joint receives contributions from

•the medial superior and inferior, lateral superior and inferior, and middle genicular arteries;

BOX 21.4: CLINICAL CORRELATION

POPLITEAL ANEURYSM

Aneurysms of the popliteal artery are the most common peripheral arterial aneurysm. They can be distinguished by a thrill (palpable pulse) and bruits (abnormal arterial sounds) overlying the popliteal fossa. Because the artery lies deep to the tibial nerve, an aneurysm may stretch the nerve or occlude its blood supply. Pain from nerve compression is referred to the skin overlying the medial aspect of the calf, ankle, and foot. Half of all popliteal aneurysms remain asymptomatic, and ruptures are rare, but symptomatic patients present with distal leg ischemia from acute embolization or thrombosis. Fifty percent of patients with a popliteal aneurysm have an aneurysm in the contralateral artery, and 25% have an aortic aneurysm.

•the descending genicular artery from the thigh;

•the descending branch of the lateral circumflex artery; and

•the recurrent branches of anterior tibial and posterior tibial arteries.

—The posterior tibial artery descends into the deep posterior leg compartment to supply muscles in the deep and superficial posterior compartments (see Fig. 21.8). Its branches include

•the fibular artery, which arises in the upper leg and descends within the posterior leg compartment; and

•the medial plantar and lateral plantar arteries, which arise as the terminal branches posterior to the medial malleolus (Fig. 21.9).

—The fibular artery supplies muscles of the deep posterior compartment and, via small arteries that perforate the intermuscular septum, muscles of the lateral compartment. At the ankle it gives off

•a perforating branch that arises at the ankle and anastomoses with the anterior tibial artery and

•malleolar branches that contribute to an anastomosis around the ankle.

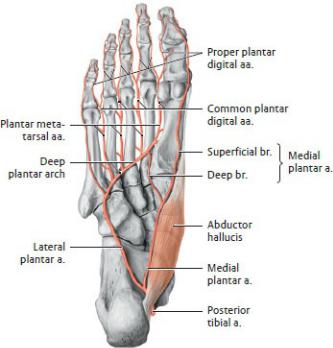

Fig. 21.9 Arteries of the sole of the foot

Right foot, plantar view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—Arteries of the sole (Fig. 21.9) arise from the posterior tibial artery and include

• the medial plantar artery, a small branch of the posterior tibial artery that

supplies the medial part of the sole;

•the lateral plantar artery, the largest branch of the posterior tibial artery, which supplies the lateral side of the sole and curves medially to anastomose with the deep plantar artery;

•a deep plantar arch, which forms through the anastomosis of the deep plantar artery and lateral plantar artery; and

•four plantar metatarsal arteries, which arise from the deep plantar arch and their branches, the common and proper plantar digital arteries,

—The anterior tibial artery passes through an opening in the interosseous membrane to supply muscles of the anterior leg compartment (Fig. 21.10). Its branches are

•proximally, a recurrent branch to the knee, and

•distally, the dorsal pedal artery as it emerges onto the dorsum of the foot.

—Arteries of the dorsum of the foot arise from the dorsal pedal artery and include

•the lateral tarsal and arcuate arteries, which form a loop on the dorsum of the foot;

•the deep plantar artery, which anastomoses with the lateral plantar artery on the sole; and

•the dorsal metatarsal arteries and their branches, the dorsal digital arteries, which arise from the arcuate artery or the dorsal pedal artery.

BOX 21.5: CLINICAL CORRELATION

THE DORSAL PEDAL PULSE

The dorsal pedal artery is readily palpable on the dorsum of the foot as it runs toward the first web space lateral to the extensor hallucis tendon. Absence of the dorsal pedal pulse suggests arterial occlusion in the peripheral vasculature.

BOX 21.6: CLINICAL CORRELATION

LOWER LIMB ISCHEMIA

Ischemia of the lower extremity is almost always related to atherosclerotic disease. Intermittent claudication is a symptom of chronic ischemic disease characterized by pain while walking, which

intensifies over time and disappears at rest. Chronic disease has a benign course and, in the majority of patients, is treated conservatively. Acute ischemia has an abrupt onset from an embolitic or thrombolytic origin and usually requires aggressive treatment. The six signs (P signs) of acute ischemia are pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesia, paralysis, and poikilothermy.

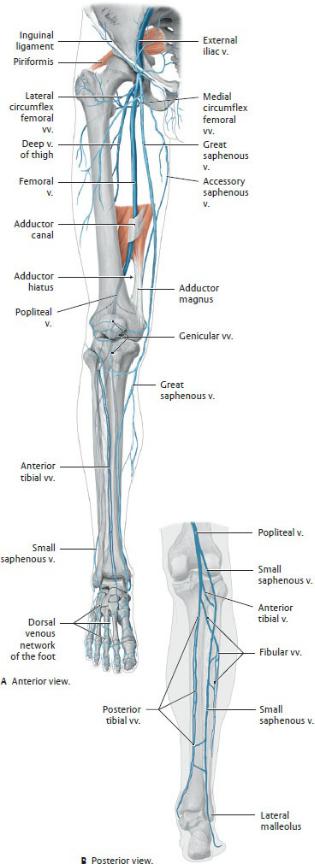

Veins of the Lower Limb

The lower limb has both deep and superficial venous drainages, which anastomose through perforating veins. Veins of both systems have numerous valves along their length.

—Veins of the deep venous system travel with the major arteries and their branches and have similar names. As in the upper limb, these deep veins usually occur as paired accompanying veins in the distal part of the limb (Fig. 21.11).

•The femoral vein, which drains the deep and superficial veins of the thigh and leg, passes under the inguinal ligament into the abdomen, where it becomes the external iliac vein.

Fig. 21.10 Arteries of the anterior leg and foot

Right leg, anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed.

New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•Superior and inferior gluteal veins, which drain the gluteal region, pass through the greater sciatic foramen to empty into the internal iliac vein of the pelvis.

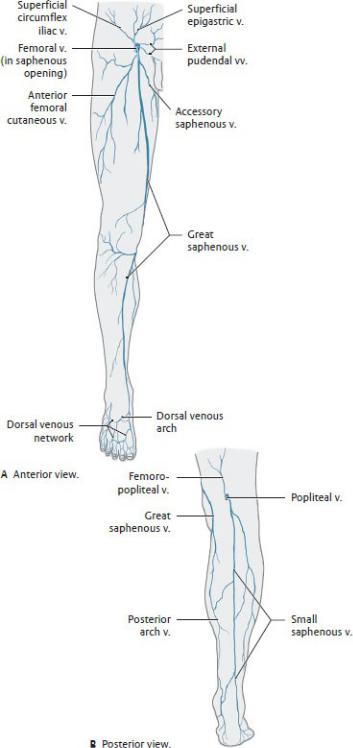

—Superficial veins are located in the subcutaneous tissue and normally drain, via perforating veins, to the deep venous system (Fig. 21.12).

•The largest superficial veins, the great saphenous and small saphenous veins, originate at the dorsal venous arch on the dorsum of the foot.

Fig. 21.11 Deep veins of the lower limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.12 Superficial veins of the lower limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 21.7: CLINICAL CORRELATION

DEEP VEIN THROMBOSES (DVT)

Thromboses (blood clots) in the deep veins of the leg result from stasis, the slowing or pooling of blood. This can result from prolonged inactivity (extended airplane travel, immobilization following surgery) or anatomic abnormalities such as laxity of the crural fascia. Thrombi from the legs can break off and travel to the heart and lungs, lodging in the pulmonary arterial tree as pulmonary emboli. Large clots can severely impair lung function and even cause death. Thrombophlebitis is the inflammation of a vein caused by thrombosis.

BOX 21.8: CLINICAL CORRELATION

VARICOSE VEINS

Varicose disease of the superficial veins of the lower limb is the most common chronic venous disease, affecting 15% of the adult population. Primary varices generally result from degeneration of the wall of the vein leading to dilated, tortuous vessels and incompetent venous valves. Secondary varices can develop from chronic occlusion of the deep veins with incompetence of the perforator veins. This causes a reversal of flow through the perforating veins. (Normal venous drainage flows from superficial to deep systems.) As the superficial veins dilate with increased volume, valve leaflets separate and become incompetent.

•The great saphenous vein arises from the medial side of the venous arch and passes superiorly, anterior to the medial malleolus and posteromedial to the knee. It drains into the femoral vein at the saphenous opening, an opening in the fascia lata in the upper thigh.

•The small saphenous vein arises from the lateral side of the venous arch, passes posterior to the lateral malleolus, and ascends the posterior leg. It drains into the popliteal vein behind the knee.

—The flow of blood from lower parts of the body must counter the downward force of gravity. In the lower limbs, venous return is assisted by

•the presence of valves in the veins,

•the pulsing of accompanying arteries, and

•the contraction of surrounding muscles.

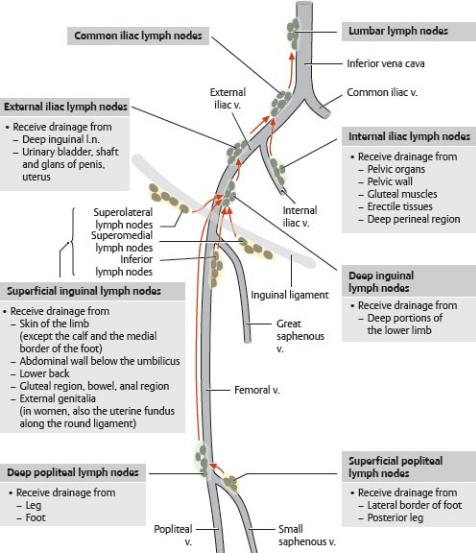

Lymphatics of the Lower Limb

Lymph from the lower limb drains superiorly from the foot following the deep and superficial veins. Upward flow is facilitated by the contraction of surrounding muscles (Fig. 21.13).

—Lymph from deep tissues of the

•gluteal region drains along the gluteal vessels to internal iliac nodes.

•thigh drains to deep inguinal nodes.

—Lymph from superficial tissues of the gluteal region and thigh drain to superficial inguinal nodes.

—Lymph from the dorsum and sole of the lateral foot and lateral leg drains along the short saphenous vein to the deep popliteal nodes at the knee. These drain directly to deep inguinal nodes.

—Lymph from the dorsum and sole of the medial foot and the medial leg drains along the long saphenous vein to superficial inguinal nodes.

—Lymph from the thigh drains first to superficial inguinal nodes, which in turn drain to deep inguinal nodes.

—Deep inguinal nodes drain sequentially to external iliac, common iliac, and lumbar nodes.

Fig. 21.13 Lymph nodes and drainage of the lower limbs

Right limb, anterior view. Arrows: direction of lymphatic drainage; yellow shading: superficial nodes; green shading: deep nodes. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

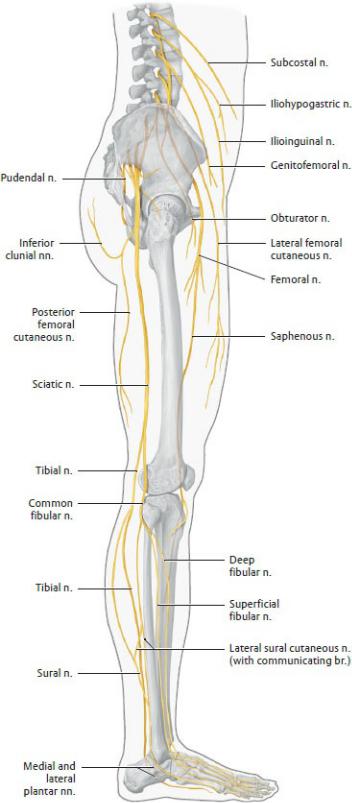

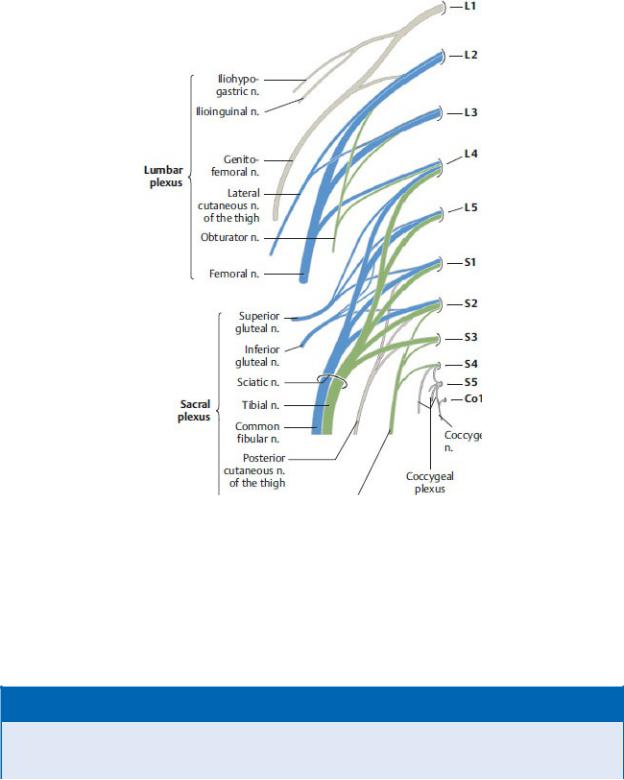

Nerves of the Lower Limb: Lumbosacral Plexus

The lumbar and sacral plexuses, often combined as the lumbosacral plexus, innervate the lower limb ( Table 21.1; Figs. 21.14, 21.15, 21.16, 21.17).

Nerves of the lumbar plexus enter the limb anteriorly to supply muscles of the anterior and medial thigh.

—The iliohypogastric (L1), genital branch of the genitofemoral (L1–L2), and ilioinguinal (L1) nerves are primarily nerves of the anterior abdominal

wall and inguinal region. They also innervate small areas of skin over the upper lateral, anterior, and medial thigh, respectively.

—The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L2–L3), a sensory nerve that enters the lateral thigh anteromedial to the anterior superior iliac spine, innervates skin of the lateral thigh.

—The femoral nerve enters the anterior thigh through the retroinguinal space (deep to the inguinal ligament), lateral to the femoral artery.

•It innervates muscles of the anterior compartment.

•Its saphenous branch is a sensory nerve that descends inferiorly to innervate the skin of the medial leg and foot.

BOX 21.9: CLINICAL CORRELATION

FEMORAL NERVE INJURY

Injuries of the femoral nerve can result in the following:

—Weakened flexion of the hip

—Loss of knee extension

—Loss of sensation on the anterior and medial thigh and medial side of the leg and foot

—Instability of the knee

Table 21.1 Nerves of the Lower Limb

Nerve |

Level |

Area of Innervation |

Lumbar plexus |

|

|

Iliohypogastric n. |

L1 |

Skin over upper lateral thigh and |

|

|

inguinal region |

Ilioinguinal n. |

L1 |

Skin over upper anterior thigh |

|

|

|

Genitofemoral n. |

L1, L2 |

Skin over upper thigh |

|

|

|

Lateral cutaneous n. of |

L2, L3 |

Skin of lateral thigh |

the thigh |

|

|

|

|

|

Femoral n. |

L2–L4 |

Iliopsoas, pectineus, sartorius, |

|

|

quadriceps femoris |

|

|

|

—Anterior cutaneous n. |

|

Skin of anterior and medial thigh |

of the thigh |

|

|

—Saphenous n. |

|

Skin of medial leg and foot |

Obturator n. |

L2–L4 |

Obturator externus, adductor |

|

|

longus, adductor brevis, adductor |

|

|

magnus, gracilis, pectineus; skin of |

|

|

medial thigh |

|

|

|

Sacral plexus |

L4–S1 |

Gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, |

Superior gluteal n. |

|

tensor fascia latae |

|

|

|

Inferior gluteal n. |

L5–S2 |

Gluteus maximus |

|

|

|

Direct branches |

L5–S2 |

Piriformis, obturator internus, |

|

|

gemelli, quadratus femoris |

|

|

|

Posterior cutaneous |

n. S1–S3 |

Skin of posterior thigh and inferior |

of the thigh |

|

gluteal region |

|

|

|

Tibial n. |

L4–S3 |

Biceps femoris (long head), |

|

|

semimembranosus, |

|

|

semitendinosus, adductor magnus |

|

|

(medial part), gastrocnemius, |

|

|

soleus, popliteus, tibialis posterior, |

|

|

flexor digitorum longus, flexor |

|

|

hallucis longus |

|

|

|

—Medial plantar n. |

|

Abductor hallucis, flexor digitorum |

|

|

brevis, flexor hallucis brevis |

|

|

(medial head), 1st lumbrical; skin |

|

|

of medial sole, 1st–3rd digits, and |

|

|

half of 4th digit |

|

|

|

—Lateral plantar n. |

|

Quadratus plantae, flexor hallucis |

|

|

brevis (lateral head), abductor digiti |

|

|

minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis, |

|

|

interossei, 2nd–4th lumbricals, |

|

|

adductor hallucis; skin of lateral |

|

|

sole, 5th digit, and half of 4th digit |

|

|

|

Common fibular n. |

L4–S2 |

Biceps femoris (short head) |

|

|

|

—Superficial fibular n. |

|

Fibularis longus and brevis; skin of |

|

|

dorsum of foot |

—Deep fibular n. |

|

Anterior tibialis, extensor hallucis |

|

|

|

|

longus and brevis, extensor |

|

|

|

digitorum longus and brevis, |

|

|

|

fibularis tertius; skin of web space |

|

|

|

between 1st and 2nd digits |

|

|

|

|

Pudendal n. |

S2–S4 |

External anal sphincter, muscles of |

|

|

|

|

the deep and superficial perineal |

|

|

|

pouches, cutaneous brs. to |

|

|

|

scrotum and labia, sensory to |

|

|

|

penis and clitoris (see Section |

|

|

|

10.6) |

|

|

|

|

Sural n. |

(tibial |

and S1 |

Skin of posterior and lateral leg |

common |

fibular |

nn. |

and lateral foot |

contributions) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 21.14 Lumbosacral plexus

Right side, lateral view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.15 Structure of the lumbosacral plexus

Right side, anterior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The obturator nerve (L2–L4) enters the medial thigh through the obturator foramen and innervates muscles of the medial compartment.

BOX 21.10: CLINICAL CORRELATION

OBTURATOR NERVE INJURY

Injury to the obturator nerve is most commonly associated with pelvic

surgery or pelvic fractures and results in the following:

—Weakened adduction of the hip (e.g., inability to move the leg from the gas pedal to the brake)

—Weakened external rotation of the hip

—Loss of sensation over a palm-size area on the medial side of the thigh

—Instability of the pelvis; lateral swing of the limb with locomotion

The sacral plexus supplies muscles of the gluteal region, posterior thigh, and all muscular compartments of the leg and foot. Its branches enter the lower limb through the greater sciatic foramen in the gluteal region.

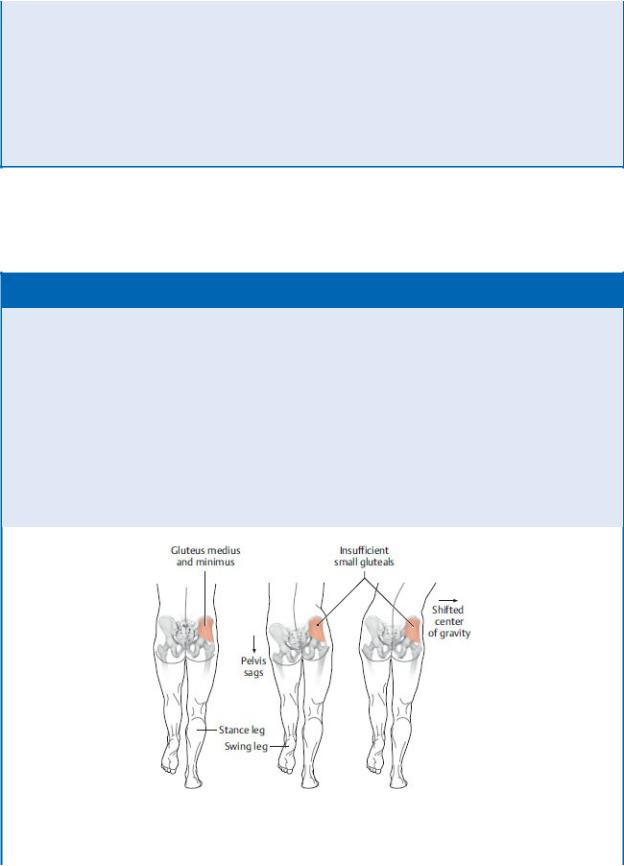

BOX 21.11: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SUPERIOR GLUTEAL NERVE INJURY

When one foot is lifted off the floor, as happens during the gait cycle, abduction of the hip by the contralateral gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles (the supported side) stabilizes the pelvis in the horizontal position. With injury to the superior gluteal nerve, the loss or weakness of abduction on that side allows the pelvis on the opposite (unsupported) side to sag. This results in a characteristic Duchenne’s limp in which the weight of the trunk is shifted toward the nervedamaged side to maintain the center of gravity.

Small gluteal muscle weakness

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York:

Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The superior gluteal nerve (L4–S1) enters the gluteal region above the piriformis muscle and runs laterally between the deep gluteal muscles. It supplies the abductors of the hip joint in the gluteal region.

—The inferior gluteal nerve (L5–S2) enters the gluteal region inferior to the piriformis muscle and innervates the large gluteus maximus muscle.

—The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L1–S3) is sensory to the thigh and posterior perineum. Its inferior clunial branches supply the inferior gluteal region.

—The sciatic nerve is made up of the tibial (L4–S3) and common fibular

(L4–S2) nerves, which are bound together in a common sheath along their course in the posterior thigh. The two nerves diverge at the apex of the popliteal fossa.

BOX 21.12: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SCIATIC NERVE INJURY

The sciatic nerve can be injured by compression by the piriformis muscle, misplaced intramuscular injections in the gluteal region, pelvic fractures, or surgical procedures such as hip replacements. An injury in the gluteal region would affect muscles of the posterior thigh and all muscular compartments of the leg, the combined effects of damage to the tibial and common fibular nerves.

—The tibial nerve, the larger branch of the sciatic nerve, separates from the common fibular nerve and continues inferiorly through the popliteal fossa into the deep posterior leg compartment.

•It innervates all of the muscles of the posterior thigh (except the short head of the biceps femoris) and the posterior leg.

•At the ankle, it passes posterior to the medial malleolus, where it terminates as the medial plantar and lateral plantar nerves.

BOX 21.13: CLINICAL CORRELATION

TIBIAL NERVE INJURY

Tibial nerve injury is unusual because the nerve is well protected in the thigh and posterior leg. Injury in the gluteal region results in the

following:

—Impaired extension of the hip

—Loss of flexion of the knee

In the popliteal fossa, it can be affected by aneurysms of the popliteal artery and knee trauma. These can cause the following:

—Loss of plantar flexion at the ankle

—Loss of plantar flexion, abduction, and adduction of the digits

—Weakened inversion of the foot

—Loss of sensation on the posterolateral leg to the lateral malleolus, the sole and lateral side of the foot

—A shuffling gait with clawing of the toes

—The medial plantar nerve, comparable to the median nerve of the hand with small motor and large sensory components, is the largest branch of the tibial nerve.

•It innervates plantar muscles on the medial side of the foot.

•A superficial branch supplies a large area of skin on the medial side of the foot and the medial three and a half digits. It terminates as three plantar digital nerves.

—The lateral plantar nerve, the smaller branch of the tibial nerve, is comparable to the ulnar nerve of the hand.

•It innervates the lateral plantar muscles and most deep muscles of the foot.

•It innervates skin on the lateral sole and lateral one and a half digits and terminates as two plantar digital nerves.

—The common fibular nerve separates from the tibial nerve and, hugging the border of the biceps femoris muscle, passes laterally around the head of the fibula where it enters the lateral leg compartment.

•In the thigh, it innervates the short head of the biceps femoris.

•In the lateral leg compartment, it splits into its terminal branches, the superficial fibular and deep fibular nerves.

BOX 21.14: CLINICAL CORRELATION

COMMON FIBULAR NERVE INJURY

The common fibular nerve is the most vulnerable of the peripheral nerves due to its exposed location around the neck of the fibula. Injuries result in the following:

—Loss of eversion of the foot

—Loss of dorsiflexion at the ankle and digits

—Weakened inversion of the foot

—Loss of sensation over the lateral leg and dorsum of the foot

—Footdrop compensated by a high-stepping gait; instability on uneven surfaces

—The superficial fibular nerve innervates the muscles in the lateral leg compartment. At the midleg, its sensory component pierces the crural fascia and runs onto the dorsum of the foot.

—From its division from the superficial fibular nerve, the deep fibular nerve circles anteriorly to enter the anterior leg compartment. It descends along the interosseous membrane, innervating all muscles of the compartment. It emerges onto the foot with the dorsal pedal artery to innervate the skin on adjacent surfaces of the 1st and 2nd digits.

BOX 21.15: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SUPERFICIAL AND DEEP FIBULAR NERVE INJURY

Injury to the superficial fibular nerve only affects eversion of the foot and sensation over the lateral leg and most of the dorsum of the foot. Injury to the deep fibular has greater functional consequences, including the loss of all dorsiflexion. This results in footdrop and the compensating high-stepping gait.

—The sural nerve (S1), formed by communicating branches of the tibial and common fibular nerves on the surface of the posterior leg, runs posterior to the lateral malleolus at the ankle to innervate the skin of the lateral foot.

Fig. 21.16 Cutaneous innervation of the lower limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 21.17 Dermatomes of the lower limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)