- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •1 Introduction to Anatomic Systems and Terminology

- •2 Clinical Imaging Basics Introduction

- •3 Back

- •4 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Spine

- •5 Overview of the Thorax

- •6 Thoracic Wall

- •7 Mediastinum

- •8 Pulmonary Cavities

- •9 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Thorax

- •10 The Abdominal Wall and Inguinal Region

- •12 Abdominal Viscera

- •13 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Abdomen

- •14 Overview of the Pelvis and Perineum

- •15 Pelvic Viscera

- •16 The Perineum

- •18 Overview of the Upper Limb

- •19 Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb

- •20 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Upper Limb

- •21 Overview of the Lower Limb

- •22 Functional Anatomy of the Lower Limb

- •23 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Lower Limb

- •24 Overview of the Head and Neck

- •25 The Neck

- •26 Meninges, Brain, and Cranial Nerves

- •29 Clinical Imaging Basics of the Head and Neck

- •Index

18 Overview of the Upper Limb

The upper limb is designed for mobility and dexterity. Actions at the shoulder and elbow joints that allow positioning of the limb complement fine movements of the hands and fingers. Some stability is sacrificed for this extensive mobility, particularly in the shoulder, which makes the upper limb vulnerable to injury.

18.1 General Features

—In the anatomic position, the upper limbs hang vertically with the elbow joint pointing posteriorly and the palm of the hand facing anteriorly.

—The major regions of the upper limb (Fig. 18.1) are

•the shoulder region, which includes the pectoral, scapular, deltoid, and lateral cervical regions and overlies the pectoral (shoulder) girdle;

•the axilla (axillary region), the armpit;

•the arm (brachial region), between the shoulder and elbow;

•the cubital region, at the elbow;

•the forearm (antebrachial region), between the elbow and wrist;

•the carpal region, at the wrist; and

•the hand, which has palmar and dorsal surfaces.

—Movements at joints of the upper limb include

•flexion, bending in a direction that narrows the distance between ventral surfaces, as represented in the embryo (in the upper limb, ventral surfaces can be interpreted as anterior surfaces, but in the lower limb, due to rotation of the limbs during development, some ventral surfaces have rotated to the posterior surface);

•extension, bending, or straightening in the direction that is opposite that of flexion;

•abduction, movement away from a central axis;

•adduction, movement toward a central axis;

•external (lateral) rotation, outward rotation around a longitudinal axis;

•internal (medial) rotation, inward rotation around a longitudinal axis;

•circumduction, circular motion around the point of articulation;

•supination, turning the palm up;

•pronation, turning the palm down;

•radial or ulnar deviation, angling the wrist toward the radius or ulnar side (also abduction or adduction of the wrist); and

•opposition, movement of the thumb or 5th digit to oppose the other fingers.

—Muscles of the upper limb are categorized as

•intrinsic muscles, whose origin and insertion are near the joint (e.g., intrinsic muscles of the hand originate and insert on bones of the wrist and hand), and

•extrinsic muscles, whose origin is distant from the area of movement but insert near the joint via a long tendon (e.g., forearm muscles that flex the fingers are extrinsic muscles of the hand).

◦The tendons of extrinsic muscles are often referred to as long flexor

(or extensor) tendons.

◦Synovial tendon sheaths, which surround tendons of extrinsic muscles at the wrist and fingers, provide a lubricated surface that facilitates movement of these tendons across the joint.

Fig. 18.1 Regions of the upper limb

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

18.2 Bones of the Upper Limb

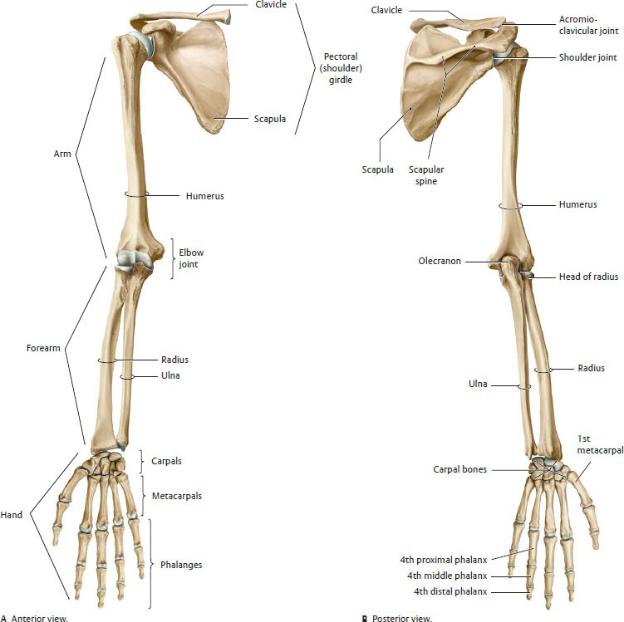

Bones of the upper limb include the clavicle and scapula that make up the pectoral girdle, the humerus of the arm, the radius and ulna of the forearm, the carpal bones of the wrist, and the metacarpal bones and phalanges of the hand

(Fig. 18.2).

—The pectoral girdle attaches the arm to the trunk (Fig. 18.3).

—The clavicle is an S-shaped bone that forms the anterior part of the pectoral girdle (Fig. 18.4).

•It articulates with the clavicular notch of the manubrium medially and the acromion of the scapula laterally.

•It is palpable along its entire length.

BOX 18.1: CLINICAL CORRELATION

CLAVICULAR FRACTURES

Fractures of the clavicle are common, particularly in children. A midclavicular fracture may be displaced by the upward pull of the proximal segment by the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the downward pull of the distal fragment by the weight of the upper limb. Distal clavicular fractures may disrupt the acromioclavicular joint or the coracoclavicular ligaments.

Fig. 18.2 Skeleton of the upper limb

Right limb. The upper limb is subdivided into three regions: arm, forearm, and hand. The pectoral (shoulder) girdle (clavicle and scapula) joins the upper limb to the thorax at the sternoclavicular joint. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.3 Shoulder girdle in situ

Right shoulder, superior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The scapula is a flat triangular bone that forms the posterior part of the pectoral girdle (Fig. 18.5).

•It overlies the 2nd to 7th ribs on the posterior thoracic wall.

•It has medial, lateral, and superior borders and a superior and inferior angle.

•Laterally, a shallow depression, the glenoid cavity, articulates with the humerus.

•A narrow neck separates the glenoid cavity from the large body of the scapula.

•A subscapular fossa lies on the anterior surface against the rib cage.

•The spine of the scapula on the posterior surface separates the supraspinous and infraspinous fossae. Laterally, the spine expands to form the acromion.

•A coracoid process extends anteriorly and superiorly over the glenoid cavity.

Fig. 18.4 Clavicle

Right clavicle.

Fig. 18.5 Scapula

Right scapula. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York:

Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The humerus is the long bone of the arm (Fig. 18.6).

•Proximally, the head articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula.

•Anteriorly, an intertubercular groove separates the greater and lesser tubercles.

•An anatomic neck separates the head from the greater and lesser tubercles. The surgical neck is the narrow part of the shaft immediately distal to the head and tubercles.

Fig. 18.6 Humerus

Right humerus. The head of the humerus articulates with the scapula at the glenohumeral joint. The capitulum and trochlea of the humerus articulate with the radius and ulna, respectively, at the elbow joint.

BOX 18.2: CLINICAL CORRELATION

HUMERAL FRACTURES

Fractures of the proximal humerus are very common and occur predominantly in older patients who sustain a fall onto the outstretched arm or directly onto the shoulder. Three main types are distinguished.

Extra-articular fractures and intra -articular fractures are often accompanied by injuries of the blood vessels that supply the humeral head (anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries), with an associated risk of post-traumatic avascular necrosis.

Fractures of the surgical neck can damage the axillary nerve and fractures of the humeral shaft and distal humerus are frequently associated with damage to the radial nerve.

•A deltoid tuberosity on the midshaft is a site for attachment of the deltoid muscle.

•A radial groove runs obliquely around the posterior and lateral surfaces.

•Distally, the humerus articulates with the radius at the capitulum and with the ulna at the trochlea.

•A large medial epicondyle and smaller lateral epicondyle are attachment sites for muscles.

•An ulnar groove separates the medial epicondyle and trochlea.

—The ulna is the medial bone of the forearm (Fig. 18.7).

•A C-shaped trochlear notch, formed by the olecranon posteriorly and the coronoid process anteriorly, articulates with the trochlea of the humerus.

•The ulna articulates with the radius at the radial notch.

•An interosseous membrane joins the shafts of the radius and ulna.

•An ulnar styloid process projects from its distal end.

—The radius is the lateral bone of the forearm (see Fig. 18.7).

•A round radial head articulates with the humerus and ulna and sits on top of a narrow neck.

•A radial tuberosity on the anterior surface provides attachments for the biceps brachii muscle.

•Distally, the radius is triangular in cross section with a flattened anterior surface.

•The radius articulates with the ulna proximally at the elbow and distally at the wrist. The interosseous membrane attaches the radius to the shaft of the ulna.

•A radial styloid process projects from the distal end and extends farther than the styloid process of the ulna.

•The radius articulates with carpal bones at the wrist.

Fig. 18.7 Radius and ulna

Right forearm, anterosuperior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 18.3: CLINICAL CORRELATION

COLLES’ FRACTURES

A Colles’ fracture, a transverse fracture through the distal 2 cm of the

radius, is the most common forearm fracture and results from a fall on an outstretched hand. The distal segment of bone is displaced dorsally and proximally, and with shortening of the radius, the styloid process appears proximal to the styloid of the ulna. The resulting appearance is referred to as the “dinner fork” deformity.

(From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The carpal bones consist of eight short bones that are arranged in two curved rows at the wrist (Figs. 18.8 and 18.9). From lateral to medial, they are

•in the proximal row, the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform; and,

•in the distal row, the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate.

BOX 18.4: CLINICAL CORRELATION

LUNATE DISLOCATION

The lunate is the most commonly displaced of the carpal bones. Normally located in the floor of the carpal tunnel, a displaced bone moves toward the palmar surface and can compress structures of the carpal tunnel.

Fig. 18.8 Bones of the hand

Right hand, palmar view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 18.5: CLINICAL CORRELATION

SCAPHOID FRACTURES

Scaphoid fractures are the most common carpal bone fractures, generally occurring at the narrow waist between the proximal and distal poles. Because the blood supply to the bone is transmitted via the distal segment, fractures at the waist (A, right scaphoid, red line; B, white arrow) can compromise the supply to the proximal segment,

often resulting in nonunion and avascular necrosis.

—The metacarpal bones consist of five long bones that form the hand.

•Proximally, their bases articulate with the carpal bones.

•Distally, their heads, the knuckles of the hand, articulate with the proximal phalanges.

—The phalanges are small long bones that form the fingers.

•They are designated as proximal, middle, and distal in each finger except in the thumb, which has only a proximal and a distal phalanx.

—Fingers and their corresponding metacarpals and phalanges are designated as 1st through 5th, with the thumb as the 1st digit and the little finger as the 5th digit.

Fig. 18.9 Bones of the hand

Right hand, dorsal view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

18.3 Fascia and Compartments of the Upper

Limb

—Deep fascia snugly encloses muscles of the upper limb. It is continuous over the pectoral girdle, the axilla, and the upper limb but has regional designations.

• Pectoral fascia invests the pectoralis major muscle.

•Clavipectoral fascia invests the subclavius and pectoralis minor muscles.

•Axillary fascia forms the floor of the axilla.

•Brachial fascia invests muscles of the arm.

•Antebrachial fascia invests muscles of the forearm and extends onto the wrist as transverse thickened bands, the flexor and extensor retinacula.

•Fascia of the hand is continuous over the dorsum and palm, but in the center of the palm it forms a thickened fibrous sheet, the palmar aponeurosis.

•Digital fibrous sheaths, extensions of the palmar aponeurosis onto the fingers, surround the flexor tendons.

—Intermuscular septa arising from the deep fascia attach to the bones of the arm, forearm, and hand, separating the limb musculature into discrete compartments. The muscles within each compartment usually share a similar function, innervation, and blood supply. The compartments of the upper limb (see Figs. 19.38 and 19.39) are

•the anterior and posterior compartments of the arm;

•the anterior and posterior compartments of the forearm; and

•the thenar, hypothenar, central, adductor, and interosseous compartments of the palm of the hand.

18.4 Neurovasculature of the Upper Limb

Arteries of the Upper Limb

—The subclavian artery and its branches supply structures in the neck, part of the thoracic wall, and the entire upper limb (Fig. 18.10).

•The right subclavian artery is a branch of the brachiocephalic trunk, which arises from the aortic arch. The left subclavian artery arises directly from the aortic arch.

Fig. 18.10 Branches of the subclavian artery

Right side, anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•The subclavian arteries enter the neck through the superior thoracic aperture, pass laterally toward the shoulder, and terminate as they pass over the 1st rib.

•The subclavian artery branches that supply the neck and thoracic wall (discussed further in Section 17.3) include

◦the vertebral artery;

◦the internal thoracic artery; and

◦the thyrocervical trunk, whose branches are the suprascapular, ascending cervical, inferior thyroid, and transverse cervical arteries.

•The branches of the thyrocervical trunk that supply muscles and skin of the scapular region include

◦the transverse cervical artery and its dorsal scapular branch and

◦the suprascapular artery.

—The axillary artery, the continuation of the subclavian artery, begins at the lateral edge of the 1st rib and terminates at the lateral border of the axilla (the lower border of the teres major muscle).

—Within the axilla, the pectoralis minor muscle lies anterior to the middle third of the axillary artery, thus dividing the artery into three segments. The origins of the branches of the axillary artery show considerable variation but generally are described as arising from its proximal, middle, or distal thirds

(Fig. 18.11).

•The proximal third has one branch:

◦The superior thoracic branch supplies the muscles of the first intercostal space.

•The middle third has two branches:

◦The thoracoacromial artery divides into deltoid, pectoral, clavicular, and acromial branches.

◦The lateral thoracic artery supplies the lateral thoracic wall, including the serratus anterior muscle and the breast.

•The distal third has three branches:

◦The subscapular artery further divides into a thoracodorsal artery, supplying the latissimus dorsi muscle, and a circumflex scapular artery, supplying muscles of the scapula.

◦The anterior circumflex humeral artery.

◦The posterior circumflex humeral artery. These circumflex arteries encircle the humeral neck to supply the deltoid region

—A scapular arcade, formed by the anastomoses of the dorsal scapular and suprascapular branches of the subclavian artery, and the circumflex scapular and thoracodorsal branches of the axillary artery provide an important collateral circulation to the scapular region when the axillary artery is injured or ligated (Fig. 18.12).

—The brachial artery, the continuation of the axillary artery, begins at the lateral border of the axilla (the lower margin of the tendon of the teres major), runs superficially along the medial border of the biceps brachii muscle, and terminates at its bifurcation in the cubital fossa (anterior elbow region). Its branches (see Fig. 18.11) include

•the deep artery of the arm (deep brachial artery, profunda brachii), which arises proximally, descends on the posterior surface of the humerus, and supplies muscles of the posterior arm; its middle and radial collateral arteries communicate with the radial artery via the radial recurrent and interosseous recurrent arteries.

•the superior and inferior ulnar collateral arteries, distal branches, which anastomose with the deep artery of the arm and the ulnar artery of the forearm to supply the elbow joint.

•the radial and ulnar arteries, the terminal branches of the brachial

artery, which supply the forearm and hand.

—The arterial anastomosis around the elbow allows the ligation of the brachial artery distal to the origin of the deep artery of the arm without compromising the blood supply to the elbow region.

—The ulnar artery originates in the cubital fossa, descends along the medial side of the forearm, and crosses through a narrow space at the wrist, the ulnar canal. It terminates as the superficial palmar arch of the hand. The major branches of the ulnar artery in the forearm (see Fig. 18.11) are

•the ulnar recurrent artery, which anastomoses with ulnar collateral arteries to supply the elbow joint, and

•the common interosseous artery, which arises in the proximal forearm and branches into anterior and posterior interosseous arteries. These interosseous branches descend on either side of the interosseous membrane and supply the anterior and posterior muscle compartments of the forearm.

—The radial artery, the smaller lateral branch of the brachial artery, descends from the cubital fossa along the lateral side of the forearm to the wrist. It crosses the wrist through the anatomic snuffbox on the dorsal side, pierces the muscles between the 1st and 2nd digits, and enters the palm of the hand, where it ends as the deep palmar arch. Its branches (see Fig. 18.11) include

•the radial recurrent artery, which anastomoses with collateral branches of the deep artery of the arm to supply the elbow joint, and

•the palmar and dorsal carpal arteries, which anastomose with branches of the ulnar artery in the wrist and hand.

Fig. 18.11 Arteries of the upper limb

Right limb, anterior view. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.12 Scapular arcade

Right side, posterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—Arteries of the wrist and hand (Fig. 18.13) include

•palmar and dorsal carpal networks, which form by contributions from radial, ulnar, and anterior and posterior interosseous arteries;

•a deep palmar arch formed largely by the radial artery that gives rise to

◦the princeps pollicis artery, which follows the ulnar surface of the 1st metacarpal to the base of the thumb, where it divides into two digital branches

◦the radialis indicis, which can arise from the princeps pollicis or radial artery and courses along the radial side of the index finger

◦three palmar metacarpal arteries, which anastomose with the common palmar digital arteries;

•a superficial palmar arch formed largely by the ulnar artery, which anastomoses with the deep palmar artery via a deep palmar branch, and gives rise to

◦three common palmar digital arteries, which divide into paired

proper digital arteries that run along the sides of the 2nd to 4th digits;

•a dorsal carpal arch, formed from the dorsal carpal network, which gives rise to three dorsal metacarpal arteries that branch into dorsal digital arteries that run on the dorsal sides of the 2nd to 4th digits; and

•a 1st dorsal metacarpal artery, which arises directly from the radial artery.

Fig. 18.13 Arteries of the forearm and hand

Right limb. The ulnar and radial arteries are interconnected by the superficial and deep palmar arches, the perforating branches, and the dorsal carpal network. (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Veins of the Upper Limb

—Veins of the limbs, similar to veins of the trunk, are more variable than the arteries, and they often form anastomoses that surround the arteries they

accompany. Veins of the limbs have unidirectional valves that prevent pooling of blood in the extremities and facilitate the movement of blood back to the heart. The limbs have both deep and superficial veins.

—Deep veins accompany the major arteries and their branches and have similar names (Fig. 18.14).

•In the distal limb, the deep veins, referred to as accompanying veins (venae comitantes), are paired and surround the artery. Proximally, the pairs merge to form a single vessel.

•The axillary vein drains the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand and receives additional contributions from

◦the lateral chest wall, including the breast, and

◦the thoracoepigastric vein of the anterolateral abdominal wall.

•The subclavian vein, the continuation of the axillary vein, begins at the lateral edge of the 1st rib and receives the venous drainage from the scapular region.

Fig. 18.14 Deep veins of the upper limb

Right limb, anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

—The superficial veins are found in the subcutaneous tissue and drain into the deep venous system via perforating (connecting) veins (Fig. 18.15).

•The dorsal venous network on the dorsum of the hand drains into two large superficial veins, the cephalic and basilic veins.

•The cephalic vein originates on the lateral side of the dorsum of the

hand and ascends on the lateral side of the forearm and arm. In the shoulder, it passes through the deltopectoral groove (formed by the borders of the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles) before emptying into the axillary vein.

Fig. 18.15 Superficial veins of the upper limb

Right limb. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

•The basilic vein arises on the medial side of the dorsum of the hand and runs posteromedially to pass anterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. In the arm, it pierces the brachial fascia (at the basilic hiatus) and joins the paired deep brachial veins to form the axillary vein.

•The median cubital vein connects the cephalic and basilic veins anterior to the cubital fossa.

•The median antebrachial vein arises from the venous network of the palm, ascends on the anterior forearm, and terminates in the basilic or median cubital vein.

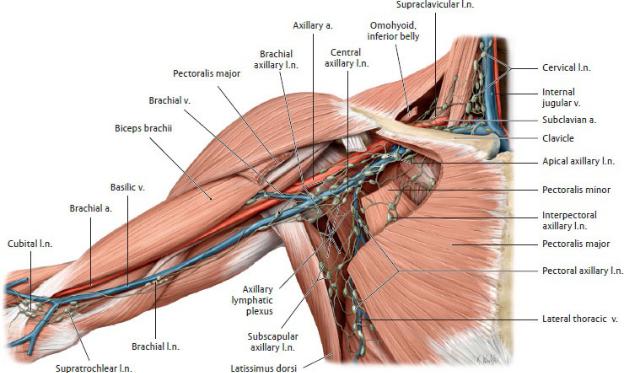

Lymphatic Drainage of the Upper Limb

Lymphatic vessels of the upper limb drain toward the axilla. They usually accompany the veins of the superficial system (cephalic and basilic veins), although there are numerous connections between the deep and superficial drainages.

—Axillary lymph node groups, each containing four to seven large nodes, are described in relation to the pectoralis minor muscle (Fig. 18.16).

•The lower axillary group lies lateral and deep to the pectoralis minor.

◦Pectoral (anterior) nodes on the anterior wall of the axilla drain the anterior thoracic wall, including the breast (75% of lymph from the breast drains to axillary nodes).

◦Subscapular (posterior) nodes along the posterior axillary fold drain the posterior thoracic wall and scapular region.

◦Brachial (lateral) nodes lie medial and posterior to the axillary vein and receive lymphatic vessels that accompany the basilic vein and the deep veins of the arm.

◦Central nodes lie deep to the pectoralis minor muscle and receive lymph from the pectoral, subscapular, and humeral nodes.

•The middle axillary group lies on the surface of the pectoralis minor muscle.

◦Interpectoral nodes lie between the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles and drain to the apical nodes.

•The upper axillary group lies medial to the pectoralis minor muscle.

◦Apical nodes lie along the axillary vein adjacent to the first part of

the axillary artery in the apex of the axilla. They receive lymph from the central nodes as well as from lymphatic vessels traveling along the cephalic vein.

—Apical lymph vessels unite to form the subclavian lymph trunks, which usually drain to the right lymphatic trunk and the thoracic duct (left lymphatic duct).

Fig. 18.16 Axillary lymph nodes

Anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

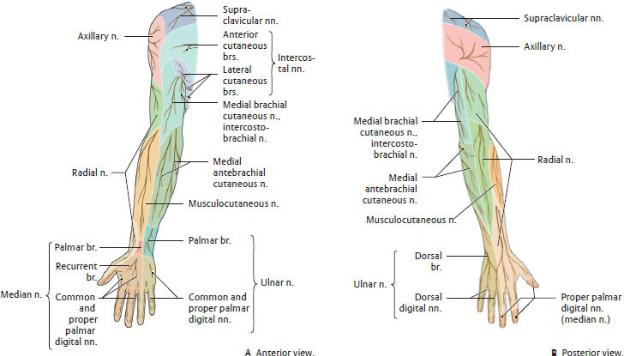

Nerves of the Upper Limb: The Brachial Plexus

The upper limb is innervated almost entirely by the nerves of the brachial plexus, which originates from the lower cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord (

Table 18.1; Figs. 18.17, 18.18, 18.19, 18.20, 18.21). (One exception, the intercostobrachial nerve, formed by the anterior rami of T1 and T2, is sensory to the medial arm but is not part of the plexus.)

—Roots of the brachial plexus emerge from the vertebral column between the anterior and middle scalene muscles (interscalene groove) in the neck.

—Formation of the plexus begins in the neck (supraclavicular part), where it

accompanies the subclavian artery, and continues into the axilla (infraclavicular part), where it accompanies the axillary artery.

—The roots, trunks, and divisions of the plexus are supraclavicular (above the clavicle); the cords form at the level of the clavicle, and their branches are infraclavicular (below the clavicle).

—Fig. 18.17 shows the architecture of the brachial plexus.

•Anterior rami of spinal nerves C5–T1 form five roots.

◦Within the plexus, upper roots form nerves that innervate muscles of the proximal limb; lower roots form nerves that innervate muscles of the distal limb.

◦The terms pre-fixed or post-fixed plexus indicate that the plexus includes anterior rami from one spinal level above (C4) or below (T2) the normal levels, respectively.

•Roots C5 to T1 combine to form three trunks: 1. C5 and C6 form the upper trunk.

2. C7 forms the middle trunk.

3. C8 and T1 form the lower trunk.

•Anterior and posterior divisions (components of the anterior rami of all spinal nerves), which are bundled together in the roots and trunks of the plexus, separate to form three cords:

1. Anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunk (C5–C7) form the lateral cord.

2. Anterior divisions of the lower trunk (C8–T1) form the medial cord.

3. Posterior divisions of all trunks (C5–T1) form the posterior cord.

•The three cords divide to form the five terminal nerves of the plexus.

◦Medial and lateral cords form the musculocutaneous, median, and ulnar nerves, which innervate the anterior muscles of the arm and forearm, and all muscles of the palm.

◦The posterior cord forms the axillary and radial nerves, which innervate muscles of the scapular and deltoid regions and posterior muscles of the arm and forearm.

Fig. 18.17 Structure of the brachial plexus

Right side, anterior view. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.18 Brachial plexus

Right side, anterior view. (See table 18.1 for explanation of color coding) (From Gilroy AM, MacPherson BR, Wikenheiser JC. Atlas of Anatomy. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 4th ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

BOX 18.6: CLINICAL CORRELATION

ROOTAND TRUNK-LEVEL INJURIES

Injuries to the proximal segments of the brachial plexus, involving the avulsion of the roots or stretching or compression of the trunks, have classic presentations that represent the distribution of the affected nerves. Nerves derived from the upper plexus innervate muscles of the proximal limb, while nerves derived from the lower plexus innervate muscles of the distal limb.

Upper plexus injuries (Erb-Duchenne palsy) involve the C5 and C6 roots or the upper trunk and are usually caused by trauma that forcefully separates the head and shoulder. The resulting deformity includes an adducted shoulder and medially rotated limb that is extended at the elbow.

Injuries of the lower plexus (Klumpke’s palsy) are far less common than those of the upper plexus, but a violent upward pull of the limb can avulse the C8 and T1 roots or damage the lower trunk. This affects the intrinsic muscles of the hand and can create a “claw hand” deformity. Because C8 and T1 are the superiormost contributions to the sympathetic trunk, avulsion of these nerve roots can also affect the sympathetic innervation in the head. The manifestation of this is known as Horner’s syndrome (see Section 28.1).

—The musculocutaneous nerve (C5–C7) pierces and innervates the coracobrachialis muscle of the arm as it leaves the axilla and then descends within the anterior compartment of the arm between the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles.

•In the arm, its muscular branches innervate the muscles of the anterior compartment, the biceps brachii and the brachialis muscles.

•It enters the forearm at the lateral edge of the cubital fossa as the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve to supply the skin of the lateral forearm.

BOX 18.7: CLINICAL CORRELATION

MUSCULOCUTANEOUS NERVE INJURY

The musculocutaneous nerve is protected on the medial side of the arm, and isolated injuries are uncommon, but they would affect the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis muscles. Flexion and supination at the elbow would be weakened but not absent because the brachioradialis and supinator muscles, which are innervated by the radial nerve, also provide those movements.

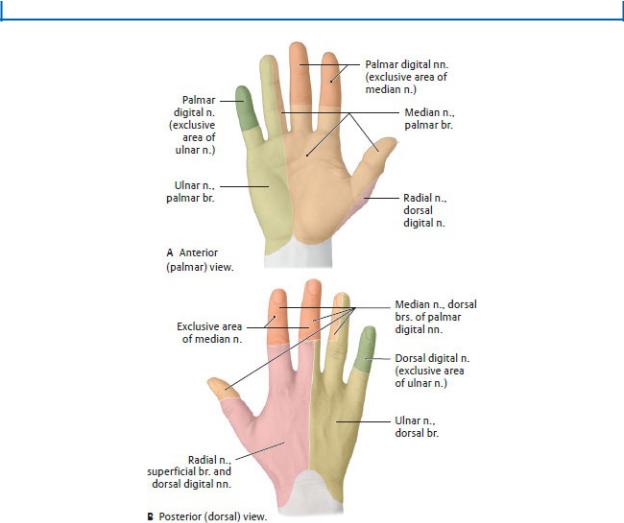

—The median nerve (C6–T1) is formed by contributions from the medial and lateral cords.

•In the arm, the median nerve descends with the brachial vessels, medial to the biceps brachii, but it does not innervate any arm muscles.

•In the forearm, it travels deep within the anterior compartment but becomes superficial at the wrist before passing through the carpal tunnel into the hand. It innervates most muscles in the anterior forearm (except the flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus).

◦Its largest branch in the forearm is the anterior antebrachial interosseous nerve.

◦A palmar branch arises distally and crosses the wrist superficial to the carpal tunnel to supply the skin of the palm.

•In the hand, the median nerve has motor and sensory functions.

BOX 18.8: CLINICAL CORRELATION

MEDIAN NERVE INJURY

Injury at the distal humerus is often caused by a supracondylar fracture and results in

•loss of sensation in the palm and palmar surface of the lateral three and a half digits,

•loss of flexion of the 1st to 3rd digits,

•positive “bottle sign” due to loss of thumb abduction (with proximal nerve lesion)

•weakened flexion of the 4th and 5th digits,

•loss of thenar opposition,

•loss of pronation,

•an “ape hand” produced by flattening of the thenar eminence, and

•the “hand of benediction” produced by flexing the hand in a fist (the 2nd and 3rd digits remain partly extended).

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

◦A thenar muscular branch, the recurrent nerve, innervates most muscles of the thenar compartment (intrinsic muscles of the thumb).

◦Palmar digital branches innervate the lateral two lumbricals (intrinsic muscles of the central compartment) and the skin of the 1st through 3rd fingers and lateral half of the 4th finger.

—The ulnar nerve [(C7) C8, T1] is a branch of the medial cord.

•In the arm, it descends on the medial side with the brachial artery. At the mid-arm, it pierces the intermuscular septum to enter the posterior compartment. It crosses the elbow joint behind the medial epicondyle, where it is subcutaneous and vulnerable to injury. It does not innervate any muscles in the arm.

•In the forearm, it runs deep to the flexor muscles but becomes superficial just proximal to the wrist.

BOX 18.9: CLINICAL CORRELATION

ULNAR NERVE INJURY

The ulnar nerve may be injured at the elbow by a fracture of the

medial epicondyle, compressed in the cubital fossa between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, or compressed in the ulnar canal at the wrist. These injuries result in the following:

•Paresthesia of the palmar and dorsal side of the medial hand and the medial one and a half digits

•Loss of thumb adduction

•Hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints

•Loss of extension of interphalangeal (IP) joints

•Weakened adduction and flexion of the wrist (for lesions at the elbow)

•Inability to form a fist due to “claw hand” deformity

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

◦Its muscular branches innervate the flexors on the medial side (flexor carpi ulnaris and medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus).

◦Palmar and dorsal cutaneous nerves arise in the wrist but are distributed to the skin of the medial half of the hand, proximal parts of the 5th digit, and medial half of the 4th digit.

•It crosses the wrist with the ulnar artery within a narrow space, the ulnar canal, where it splits into deep and superficial branches.

◦Its deep branch supplies most of the intrinsic muscles of the palm (except the adductor pollicis, half of the flexor pollicis brevis, and the 1st and 2nd lumbricals).

◦Its superficial branch innervates a small superficial muscle of the palm (palmaris brevis) and contributes to sensory innervation of the 4th and 5th digits.

—The axillary nerve (C5–C6), a branch of the posterior cord, passes to the posterior shoulder region with the posterior circumflex humeral vessels.

•In the shoulder region, it innervates scapular and deltoid muscles and skin of the deltoid region.

BOX 18.10: CLINICAL CORRELATION

AXILLARY NERVE INJURY

The axillary nerve is most vulnerable as it courses around the neck of the humerus and can be injured by fractures at the surgical neck or dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. Denervation of the deltoid results in substantial functional weakness of shoulder movements and other effects, including

•Weakened flexion and extension at the shoulder joint

•Inability to abduct the shoulder even to the horizontal position

•Loss of sensation over the deltoid region

•A flattened shoulder contour

—The radial nerve (C5–T1) forms from the posterior cord.

•In the arm, it runs posteriorly around the humerus in the radial groove with the deep brachial artery and descends within the posterior compartment.

◦Its muscular branches innervate all of the muscles of the posterior arm, the triceps brachii and anconeus muscles.

◦Its sensory branches of the arm include the posterior brachial cutaneous and inferior lateral brachial cutaneous nerves.

◦A posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve arises in the arm but

innervates skin over the posterior forearm.

•In the cubital region, it passes through the lateral intermuscular septum into the anterior compartment, where it runs anterior to the lateral epicondyle. As it enters the proximal forearm, it splits into deep and superficial branches.

◦The deep branch becomes the posterior interosseous nerve as it circles around the radius into the posterior forearm compartment. It innervates all muscles of this compartment.

◦The superficial branch descends along the lateral forearm to the wrist.

•In the hand, the radial nerve has no motor branches.

◦At the wrist, the superficial branch runs posteriorly to innervate the skin on the dorsum of the hand and proximal segments of the 1st through 3rd digits and half of the 4th digit.

BOX 18.11: CLINICAL CORRELATION

RADIAL NERVE INJURY

The radial nerve is most vulnerable to injury from a midhumeral fracture where the nerve courses along the radial groove. Because radial branches to the triceps brachii are usually proximal to the injury, elbow flexion is unaffected. Other effects include the following:

•Loss of wrist extension

•Loss of extension at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints

•Weakened pronation

•Flexed wrist and fingers producing the “wrist drop” position

“Wrist drop” resulting from loss of wrist extensors.

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.19 Sensory innervation of the hand

Right hand. Extensive overlap exists between adjacent areas. Exclusive nerve territories indicated with darker shading. (From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.20 Cutaneous innervation of the upper limb

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)

Fig. 18.21 Dermatomes of the upper limb

(From Schuenke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Vol 1. Illustrations by Voll M and Wesker K. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme Publishers; 2020.)