Итог_№ 2_2022 ТГиП

.pdf

Theory of State and Law

12.Борьба с жилищным кризисом // Красное знамя. – 1923. – № 183. – С. 3.

13.Временная инструкция НКВД по планировке и застройке участков, отводимых

впределах городской черты для жилищного строительства // Жилищное законодательство. Сборник декретов, распоряжений и инструкций с комментариями / сост. Д.И. Шейнис. – М., 1926. – 350 с.

14.Гербовый сбор с договоров и сделок (их оформление и свидетельствование). – Вып. 11. – Казань, 1925.– 43 с.

15.Гражданскийкодексввопросахиответах/подред.Ф.И.Вольфсона.–М.,1929.–205с.

16.Декрет ВЦИК, СНК от 10 августа 1922 г. № 645 «О праве застройки земельных уча- стков» //URL:http://xn--e1aaejmenocxq.xn--p1ai/node/13807 (дата обращения 25.01.2022).

17.ЖилищныйвопроспозаконодательствуРСФСР/сост.О.Б.Барсегянц.–М.,1922.–70с.

18.Жилищное законодательство. Сборник декретов, распоряжений и инструкций с комментариями / сост.Д.И. Шейнис. – М., 1926.– 350 с.

19.Меерович М. Градостроительная политика СССР (1917–1929). От города-сада к ведомственному рабочему поселку. – М., 2017. – 352 с.

20.Меерович М. Г. Наказание жилищем: жилищная политика в СССР как средство управления людьми (1917–1937). – М., 2008. – 303 с.

21.Милищенко О. А., Кравцева Н. А., Баженов В. П., Цыплёнкова И. В. Омская «Нахаловка»: формы собственности на жильё, юридическое обременение участков и строений домовладельцев, правила прописки // Электронный научно-методический журнал Омского ГАУ. – 2019. – № 4 (19). // URL: https://e-journal.omgau.ru/images/issues/ 2019/ 4/00777.pdf. (дата обращения 11.01.2022).

22.Охрана жилищных интересов трудящихся в спорах с застройщиком // Еженедельник советской юстиции. – 1926. –№ 4. – С. 107.

23.Сытин П.В. Коммунальное хозяйство (благоустройство) Москвы в сравнении с благоустройством других больших городов. – М., 1926. – 230 с.

24.Широкая дискуссия по жилищному вопросу. Жилищный вопрос и Уголовный кодекс // Еженедельник советскойюстиции. – 1922. – № 34. – С. 14.

25.Ящук Т.Ф. Декрет ВЦИК от 20 августа 1918 года «Об отмене права частной собственности на недвижимости в городах» как правовая основа муниципализации // Историкоправовые проблемы: новый ракурс. – 2013. – № 6. – С. 191–213.

Для цитирования: Микуленок Ю.А. Правовое регулирование частной застройки в период НЭПа: статья // Теория государства и права. – 2022. – № 1 (26). – С. 166–171.

DOI: 10.47905/MATGIP.2022. 27.2.015

Julia A. Mikulenok*

LEGAL REGULATION OF PRIVATE DEVELOPMENT

DURING THE NEP PERIOD

Annotation. The article deals with one of the acute issues facing the Soviet government – housing. The problems that were not solved during the tsarist period worsened in the first decade after the October Revolution and intensified the "housing famine". The new housing policy only slightly improved the living conditions of the workers, so the Soviet government resumed private construction. However, the housing sector was still under the jurisdiction of the State. The land continued to remain the property of the state, the state, through municipal departments, allo-

* Mikulenok Julia Andreevna, PhD in history, Associate Professor, Department of General Theoretical Disciplines North Caucasus Branch of the Russian State University of Justice. E-mail: AK-bara@yandex.ru.

171

Теория государства и права

cated planned plots on which new houses were allowed to be built, and strictly controlled private housing construction. Housing legislation of the 1920s regulated sanitary building and building codes, building materials.

The article provides specific examples of the content and conditions of concluded contracts for housing construction.

Key words: NEP, private development, development contract, housing construction, housing cooperation.

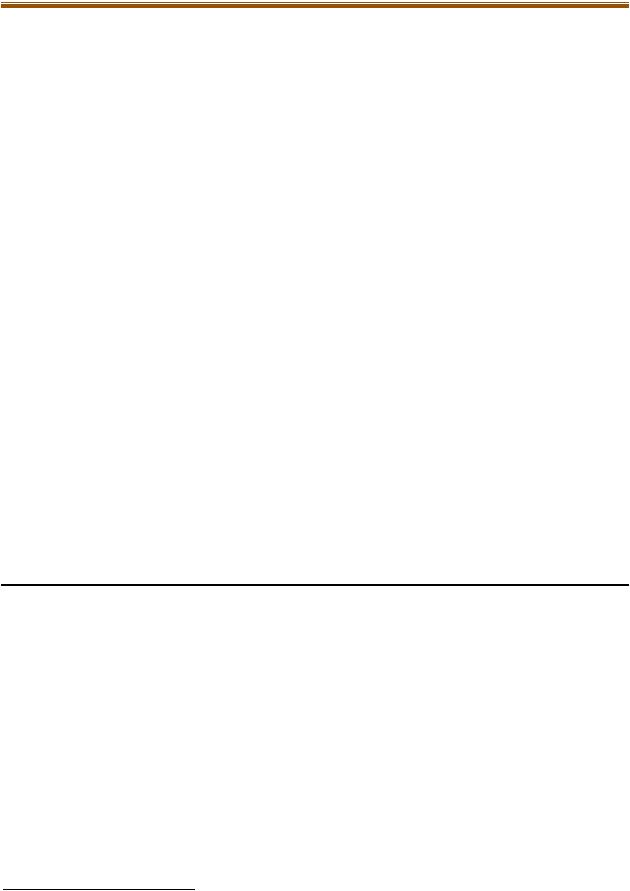

Introduction. The first decade after the establishment of Soviet power was a difficult period of political and socio–economic transformation of Russia, which aggravated the issues previously unresolved by the tsarist government. Especially acute in the 20s of the last century was the "housing issue". During the years of the Civil War and war communism, the housing stock of Soviet Russia, due to objective and subjective reasons, which we will not dwell on in this article, has significantly, decreased. So, for the first five years after the revolution, Moscow lost 25% of the housing stock. On average, the citizens of Soviet Russia were not even provided with a minimum sanitary norm of 8–10 m2. The table below shows the average rate of living space per person at the peak of the "housing famine".

|

Moscow |

Petrograd/ |

Krasnodar |

Novorossiysk |

Rostov-on-Don |

|

Leningrad |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

1923 г. |

6,5 m2 |

12,5 m2 |

4,9 m2 |

4,82 m2 |

4,5 m2 |

The dwellings were so destroyed that maintaining them from further destruction and keeping them in a satisfactory sanitary condition was the main task of the Soviet government [24, p. 14].

Trying to solve the housing issue, the authorities have embarked on a "new housing policy": the municipalization of housing, the policy of "infringement" and eviction of "exes", the creation of shelters, the minimum sanitary norm and differentiated payment for square meters are introduced. In 1918, the right of private ownership to all plots without exception was abolished [25, p. 191]. After the October Revolution, a significant part of the living space was under the jurisdiction of communal departments, which were assigned the following tasks: distribution of square meters; collection of rent; check-in, eviction or consolidation of citizens [21]. It is worth noting that this policy could not satisfy all those in need of housing. The workers were forced to occupy unsuitable premises: damp, dark rooms, corridors, basements or semi-basements, barracks, sheds, etc.

The right of private development. Objectively, the Soviet government could not eliminate the "housing famine" by starting mass housing construction, so with the advent of the NEP, private construction resumed again. The decrees of the Council of People's Commissars "On the Demunicipalization of residential buildings" and "On the unloading of Municipal Bodies from the direct operation of the municipal fund and the transfer of houses to tenant collectives" reanimated private ownership of residential buildings. However, the Soviet government was ready to encourage the private construction of sites that could not be built up by means of local executive committees [18, p. 13], or the completion of houses by institutions or individuals. The Soviet leadership was attracted only by the construction of multi-storey houses [19, pp. 208–209], as evidenced by the constant party discussions, at which party leaders repeatedly said that individual construction of the type of European cottages is not suitable for Soviet Russia [3, p. 117]. The practice of individual construction has been repeatedly criticized on the pages of the periodical press. However,

172

Theory of State and Law

an analysis of the registration books of private households shows that mostly citizens were attracted by the construction of individual houses designed for one family. In Krasnodar alone, in 1920, 2,000 small holiday houses (an old residential structure made of wood and clay) were built for families of 4–5 people [6, p. 3].

Housing legislation, encouraging private construction, provided certain benefits for developers: for the first three years they did not pay rent at all and for the rest of the contract period they paid half the amount if the living area was at least 75% of the total cubic capacity of the building [15, p. 41]. The developer was granted the right to set a fee for residential premises [22, p. 107].

In the 20s, several types of private construction can be distinguished: individual and cooperative. It is worth noting that the concept of "private development" within the framework of the Soviet housing and urban planning policy was transformed [19, p. 211]. The housing sector, including private development, was strictly controlled by the Main Department of Public Utilities [20, p. 221] (the executive body of the NKVD). The main functions of the Main Department of Public Utilities were control over individual housing construction, rationing of construction, development of residential buildings and operation management [19, p. 212]. The Departments of State Structures of the Council of National Economy formed sub-departments of urban and rural construction, which were responsible for all civil construction in cities [7, p. 34a].

Projects, materials, sanitary standards – everything was subject to regulation. For example, having considered the project of a two-storey house of the housing and construction association "Svyaz" on 56 Kommunarov St., compiled by engineer Sosnov, the Office of the Kuban District Engineer found a number of significant shortcomings in it that needed to be eliminated:

"1) Since the facade faces the street, it is necessary to give it such a look that, in addition to simplicity, it gives at least a minimum of architecture.

2)The scales should be outlined so that they can be understood and used.

3)The height of the rooms should not be more than 3.20 meters. <…>

5)All chimneys located in the outer walls must be at least 1 ½ bricks away from the outer surface of the wall.

6)All water closets must be provided with ventilation.

7)There are no chimneys and hoods for the kitchen hearths of the left front apartments of both floors. <…>

9)The partitions separating the apartments of the old part of the building and the superstructure above it must be made of fireproof material. <…>

12)Doors should not fall into partitions, as, for example, in the left front apartment of the 1st floor.

13)Redesign the porch of the exit to the courtyard. <…>

16)Cluttering kitchens with bathrooms with speakers is hardly advisable.

17)The size of the furnaces in the left apartments of both floors is disproportionately large. <...>" [5, p. 10 (about)].

The right of development arose under a contract (concluded in a notarial manner) between the owner of the land and a person wishing to build on this land [18, p. 7]. Since in Soviet Russia the land was the property of the state, therefore, only the state could grant the right of development through the municipal departments of Executive committees [14, p. 11] by allocating planned plots. So, in Krasnodar from 1923 to 1926, 2,800 planned places were allocated for construction (city gardens along the streets of Novorossiysk, Stavro-

173

Теория государства и права

pol and gardens to the east of the Club) [8, p. 12]. In Moscow by January 1, 1924 320,200 sq. s. were built with a living area of 213,467 sq. s., which could accommodate more than 120,000 people [23, p. 80]. In 1927, 67 construction permits were issued in Rostov-on-Don [10, p. 45].

The right of development could be alienated, encumbered with collateral and inherited, but it was valid only within the limitation period of the contract [18, p.7]. After the expiration of the contract, all buildings had to be handed over by the developer in good condition to the municipal department, which paid the developer the cost of the buildings by the time they were handed over [18, p. 12].

According to Soviet housing law, a building contract is a real right, conditioned by a certain period of time, to own and use a land plot as a construction area, and possession and use were limited to a specific purpose – the construction of a land plot. In the contract on the right of development, it was mandatory to specify: a) the name of the contracting parties, b) the term of the contract (40 years for wooden buildings and 60 for stone ones.

According to the decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR of August 27, 1928 "On benefits for the construction of dwellings at the expense of private capital", the deadline for contracts on the right of construction by private individuals of large houses was set at 80 years for stone, reinforced concrete and mixed buildings and at 60 years for wooden [15, p. 39]), c) the exact definition of the plot to be built, d) the amount in gold rubles and the term of the rent payment, e) the nature and size of the buildings that the developers undertake to erect, f) the start date for construction, g) the completion date of construction, h) the conditions for maintaining the buildings in good condition, and) conditions of insurance of buildings and their restoration in case of death, k) penalties in case of delay and other violations of the contract by the developer [16].

When starting construction, citizens had not only to obtain a construction permit from the municipal department, but also to provide a sketch of the development project corresponding to the established long-term urban construction plans, building rules and regulations [1, p. 227].

When drawing up the draft project, the following tasks were taken into account:

a)determining the direction of expansion of the city;

b)the establishment of the division of the city into districts: industrial, commercial, administrative and residential, of which there may be several in the city;

c)determination of the main routes and highways within the city limits to railway stations, to marinas, commercial, industrial and administrative centers with the width corresponding to their value;

d)definition of construction areas of both existing and proposed development;

e)designation of squares, public gardens, parks, boulevards, sports grounds, etc. by

districts;

f)identification of agricultural areas and satisfaction of the needs of camps, farms, nurseries, sanatoriums, urban treatment facilities and water supply sources [17, p. 15].

The building plan had to be of a simple shape, with a reduction in expensive exterior walls, which strongly cooled the room in winter. In order to get a larger wall area, the municipal department recommended limiting the number of windows and doors [11, p. 125].

The legislator made the following requirements for apartments. They should be separated by a partition or walls from the neighboring apartment. Each living room should have an area of at least 9 m2, be at least 2.70 m high. Rooms should be illuminated by direct

174

Theory of State and Law

light, windows should be at least 1/10 of the floor area. Only wooden floors are allowed in living rooms. During the construction of the walls, it was allowed to use brick or wood [18, p. 26]. For multi-storey buildings, foundations should be laid below the freezing line [13, p. 29]. The size of the plots allocated for individual construction should have been at least 600 m2 [18, p. 21]. However, local authorities could reduce this norm [8, p. 106].

During the construction of buildings, as well as their operation, the developer was obliged to comply with the established building codes, as well as sanitary and fire safety rules [18, p. 11]. Working housing had to be economical. The general requirements imposed on the workhouse stemmed from the full expediency of the whole house as a whole and each of its premises separately, in compliance with all the necessary requirements of convenience and hygiene, on the one hand, and reducing to the possible minimum the costs associated with the construction of a workhouse, on the other. The minimum size of the house is one living room, a separate kitchen and the necessary amenities. With a large family – one or two rooms for bedrooms and a common family room, which can be combined with a kitchen [11, p. 124].

When choosing land plots for working dwellings, the following conditions must be met: a) the sanitary suitability of the site for construction; b) the convenience of communication with the place of work of workers; c) the proper size of the site [13, p. 20].

The building site should be dry, drained and landscaped, i.e. all communications should have been carried out: water supply, dirt roads, drains, street lighting; a device for collecting, storing and removing sewage [18, p. 33]. Due to the fact that it was forbidden to allocate plots located near urban landfills, slaughterhouses and cemeteries for construction [18, p. 20–21], all buildings that did not meet these requirements were demolished. So, a household located behind the city cemetery of Krasnodar, on the territory of a former landfill, was demolished in 1928 [4, p. 174 (ob)].

In the 20s, housing and construction cooperative partnerships (HSCT) appeared, which united employees, workers and persons employed by private individuals. The main tasks of the Housing and communal services were the construction of new residential buildings and the restoration of destroyed buildings. However, for the majority of citizens, housing cooperation turned out to be an unbearable burden and workers and employees with a salary of at least 70 rubles per month could actually participate in housing cooperation. On average, participants in cooperative construction contributed 1 rub. 60 kopecks in gold [12, p. 3] for 1 m2 per month, excluding utilities. If we take into account the cost of utilities, then the amount of payments reached from 3 rubles [3, p. 131] up to 5 rubles per month. On average, one family needed an apartment of about 20 m2. Thus, it was necessary to pay at least 60 rubles per month [2, p. 30].

Conclusion. The first decade after the establishment of Soviet power was marked by an acute "housing famine", solving the problem of which, the new government reanimated private development again. Despite certain easing of the NEP, the development was completely under the control of the state: the allotment of land, the development plan, which was supposed to correspond to the long-term urban development plan for the next 20–30 years, and building materials and standards.

The ideal for the implementation of state policy in the field of housing construction was the construction of multi-storey cooperative houses, however, the high cost of building materials did not allow everyone to participate in housing and construction cooperation, and single-storey houses designed for one family became the predominant type of housing.

175

Теория государства и права

Conflict of interest.

The authors confirm the absence of a conflict of interest.

Bibliographic list

1.The State Archive of theRussian Federation (GARF). F. R-374. Op. 21. D. 9.

2.GARF. F. R-1235. Op. 62. D. 3.

3.The Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI). F. 17. Op. 2.D. 233.

4.The State Archive of theKrasnodar Territory (GACC). F. R-226. Op. 1. D. 426.

5.GACC. R-262. Op. 1. D. 359.

6.GAKK. F. R-262. Op. 1. D. 362.

7.GAKK. F. R-942. Op. 1. D. 60.

8.GAKK. F. R-1547. Op. 1. D. 27.

9.GAKK. F. R-1547. Op. 1. D. 28.

10.The State Archive of the Rostov region (GARO). F. R-1185. Op. 2. D. 369.

11.Barkhin G.B. Working house and working village-garden. Moscow,1922.263 p.

12.Fighting the housing crisis // Red Banner. 1923. No. 183. P. 3.

13.Temporary instruction of the NKVD on the planning and construction of plots allocated within the city limits for housing construction // Housing legislation. Collection of decrees, orders and instructions with comments / comp. D.I. Sheinis. Moscow, 1926. 350 p.

14.Stamp duty on contracts and transactions (their registration and certification). Issue 11. Kazan, 1925. 43 p.

15.The Civil Code in questions and answers / edited by F.I. Wolfson. Moscow, 1929. 205 p.

16.Decree of the Central Executive Committee, SNK of August 10, 1922 No. 645 "On the right todeveloplandplots"//URL:http://xn--e1aaejmenocxq.xn--p1ai/node/13807(accessed25.01.2022).

17.Housing issue under the legislation of the RSFSR / comp. O. B. Barseghyants. Moscow, 1922. 70 p.

18.Housing legislation. Collection of decrees, orders and instructions with comments / comp. D.I. Sheinis. Moscow, 1926. 350 p.

19.Meerovich M. Urban planning policy of the USSR (1917–1929). From the garden city to the departmental working settlement. Moscow, 2017. 352 p.

20.Meerovich M. G. Punishment by housing: housing policy in the USSR as a means of managing people (1917–1937). Moscow, 2008. 303 p.

21.Milishchenko O. A., Kravtseva N. A., Bazhenov V. P., Tsyplenkova I. V. Omsk "Nakhalovka": forms of ownership of housing, legal encumbrance of plots and buildings of homeowners, rules of registration // Electronic scientific and methodological journal of the Omsk State Agrarian University. 2019. № 4 (19). // URL: https://e-journal.omgau.ru/images/issues/ 2019/ 4/00777.pdf. (date of appeal 11.01.2022).

22.Protection of housing interests of workers in disputes with the developer // Weekly of Soviet Justice. 1926. No. 4.P. 107.

23.Sytin P.V. Communal services (landscaping) Moscow in comparison with the improvement of other largecities. Moscow, 1926. 230 p.

24.A broad discussion on the housing issue. Housing issue and the Criminal Code // Weekly of Soviet Justice. 1922. No. 34. P. 14.

25.Yaschuk T.F. Decree of the Central Executive Committee of August 20, 1918 "On the abolition of the right of privateownership of real estate in cities" as the legal basis of municipalization // Historical and legal problems: a new perspective. 2013. No. 6. Pp. 191–213.

For citation: Mikulenok Yu.A. Legal Regulation of private development during the NEP Period: article // Theoryof state and law. 2022. № 1 (26). Р. 171–176.

DOI: 10.47905/MA TGIP.2022.27.2.015

176

Theory of State and Law

Научная статья

УДК 340.0 ББК 67.0

DOI: 10.47905/MATGIP.2022. 27.2.016

А.В. Панибратцев* А.А. Романов** Т.Г. Оганесян***

ПРОЦЕССЫГЛОБАЛИЗАЦИИ И ИХ ВЛИЯНИЕ НА ПРАВОВУЮ ИДЕНТИЧНОСТЬ

Аннотация. Современный этап развития общества характеризуется повсеместным распространением глобализационных процессов, которые затрагивают абсолютно все сферы социальной жизни – право, политику, экономику, культуру, духовную сферу и т.д. Особую актуальность приобретают вопросы сохранения и трансформации идентичности в ее разнообразных ипостасях – государственной (правовой), этнической, религиозной и пр. – изучение особых отношений социальной жизни и идентичности, функциональной взаимосвязи права как средства социальной регуляции и явление идентичности, его вариация образами на ментальном уровне и репродукция правовым поведением. В этой связи авторами были рассмотрены научные точки зрения на сущность и природу глобализации, а также этнической (этнокультурной) идентичности. В ходе проведенного исследования удалось выявить, что глобализация является многомерным явлением и оказывает как негативное,такипозитивноевоздействиенаэтническуюидентичность.

Среди отрицательного влияния целесообразно отметить увеличение миграционных потоков, усиление социальной напряженности в обществе, утрата этнических ценностей, возникновение межэтнических, межрелигиозных, межконфессиональных конфликтов. Кроме того, происходит гомогенизация и универсализация идентичности, которые полностью или частично подчиняются законам и ценностям Запада. В итоге, это грозит утратой собственной этнической идентичности и поглощением этничности малых народов доминантами. Однако нельзя отрицать и выраженное позитивноевлияниеглобализационныхпроцессовнасохранениеидентичности.

В последние десятилетия наблюдается также этнофрагментация как контртенденция глобализации, когда этничность приобретает качество доминанты и происходит формирование прочных представлений о взаимосвязанном мире, этнокультурном многообразии, увеличении плотности информационно-коммуникационных связей. Отдельные этничности могут вырваться за пределы своей ограниченности и получить толчок для дальнейшего развития и институционализации. Более того, становятся

* Панибратцев Андрей Викторович, профессор кафедры гуманитарных и социально-полити- ческих наук Московского государственного университета гражланской авиации, доктор философских наук, профессор. E-mail: pasabas@yandex.ru

**Романов Александр Александрович, профессор кафедры теории и истории государства и права Юридического института (Санкт-Петербург), кандидат политических наук, доцент. E-mail: romanov@ universitas.ru

***Оганесян Тамара Геворковна, магистр юридического факультета Российского государственного социального университета.

177

Теория государства и права

доступными образование, изучение этничности и правовой культуры других народов, что позволяет обогатить свою собственную идентичность. Именно поэтому следует вычленить тот позитивный опыт, который предоставляет нам глобализация и использовать его для усиления собственной идентичности.

Ключевые слова: глобализация, философия права, идентичность, правовая идентичность, этническая идентичность, правовая политика, межэтнические конфликты.

В последние годы все большее внимание со стороны представителей научного сообщества и широкой общественности занимают вопросы групповой идентичности и проблемы ее сохранения. Это обусловлено повсеместным распространением глобализационных процессов, которые затрагивают правовые, политические, экономические, этнические, духовные и иные сферы жизнедеятельности человека. С одной стороны, эти тенденции можно рассматривать с положительной точки зрения, ведь интеграция способствует открытому общению различных этнических групп, позволяет получать образование жителям отдаленных уголков, предоставляет возможности этнокультурного обогащения, знакомит с правовой культурой, обычаями и традициями различных социумов и т.д. С другой стороны, нельзя игнорировать те проблемные моменты, которые несет в себе глобализация. Особенно сильно ее влияние на малые народы, которые более всего подвержены воздействию извне. Это может грозить для них утратой собственной идентичности и, что более серьезно, этнической ассимиляцией.

Главная цель настоящего исследования заключается в рассмотрении феномена глобализации и анализа его влияния на этническую идентичность и правовую культуру.

Для достижения заявленной цели требуется решить ряд первоочередных задач, среди которых необходимо отметить следующие:

определение сущностно-содержательной характеристики глобализации;

анализ научных точек зрения отечественных и зарубежных авторов на понятие идентичности и этнической идентичности;

философско-правовой анализ ценностного компонента идентичности, лежащий в основе формирования чувства сопричастности представителей определенной общности;

систематизация глобализационных факторов, оказывающих прямое или косвенное влияние на этническую идентичность.

Рассмотрение вопроса начнем с изучения сущностно-содержательной характеристики феномена современной глобализации. Следует подчеркнуть, что глобализация выступает неким объективным процессом развития всего мирового сообщества, который происходит независимо от воли и сознания отдельных государств, их союзов

иобъединений, от желаний этнических групп. Современную глобализацию можно представить как некую планетарную матрицу, на которой воспроизводятся сложные системы социальныхотношений,как глобальных,так илокальных обществ.

Проанализируем некоторые точки зрения, высказанные отечественными и зарубежными учеными на сущность и природу глобализации. Первые теоретические исследования процессов глобализации предприняли еще в 60-х г. XX века члены Римского клуба. В докладе «Цели для человечества» была разработана концепция «глобального общества», которая рассматривает философско-правовой аспект права

178

Theory of State and Law

вновых стандартах «гуманизма». Нормы поведения людей и правовые нормы, которые устанавливаются проводимой государством правовой политикой, должны сочетаться с философско-правовым содержанием современных ценностей: взаимопроникновением культур, демократизацией политических режимов, расширением глобальных процессов.

Первые фундаментальные упоминания глобализации были зафиксированы

в80-х годах ХХ века. Введение данного термина связано с именем Т. Левитт, который с позиции экономического детерминизма предлагал понимать глобализацию как образование универсального рынка товаров и услуг, производимых транснациональными корпорациями.

Отдельного внимания заслуживает научная позиция, высказанная М.И. Романовым, который под глобализацией понимает перманентный процесс унификации различных социальных отношений и жизнедеятельности людей. Производительные силы и производственные отношения непрерывно трансформируются в мир-экономику, которая на основе транснациональной либерализации включает в себя разнообразные экономические и политико-правовые субъекты, взаимосвязанные между собой по- литико-правовыми отношениями [7, с. 113].

Глобализация, прежде всего, рассматривается в экономическом аспекте. С этой позиции глобализация является новой формой в эволюции производительных сил и производственных отношений в виде их интернационализации в условиях качественно новой промышленной революции, когда достижения науки и техники становятся общедоступными.

Изучение глобализационных процессов в контексте мир-системного анализа показывает, что глобализация выступает как сложно-структурный процесс инкорпорации ранее слабо взаимодействующих наций и народов в общемировую экономику, а также как трансграничная правовая рецепция государственно-правовых образований [3, с. 83].

Таким образом, процессы глобализации неминуемо вносят изменения и в правовую сферу жизни общества, так как между экономикой и правом существует неразрывная взаимосвязь: правовые институты – во многом продукт экономической жизни, в свою очередь, нормы права регламентируют правила поведения для участников экономической деятельности. Иначе говоря, в условиях глобализации участники производства мир-экономики выступают не только как объекты экономической деятельности, но и как субъекты, участвующие в формировании политики и установлении правовых норм, регулирующих производственные отношения [11, с. 6]. Кучерков И.А. и Воронина Т.В. глобализацию в правовой сфере определяют как процесс формирования единообразия применяемых правовых принципов, методов правовой регламентации и правоприменительной практики. Имплементацией универсальных правовых норм в национальное законодательство формируются наднациональные механизмы правового регулирования и правоприменения [3, с. 91].

Проанализировав представленные определения термина «глобализация», приходим к выводу, что на протяжении более чем 30 лет она вызывает активные дискуссии среди авторитетных представителей научного сообщества. При этом, несмотря на повышенный интерес, до настоящего времени не сформулировано единого общепринятого определения данной дефиниции, что порождает серьезные разногласия в определении степени ее влияния на социальную жизнь. Более того, различное понимание сущности и содержания глобализации приводит к существова-

179

Теория государства и права

нию различных точек зрения относительно ее влияния на государственно-правовую, политическую, экономическую, социальную, культурную, духовную и иные сферы жизнедеятельности отдельного человека и всего общества.

Неправильно было бы отрицать тот факт, что процессы глобализации распространились по всему миру, не оставив ни единого субъекта без своего влияния в той или иной степени. Они не оставили в стороне ни один континент, страну, общество и в большей или меньшей степени нации и народы. Определенное воздействие глобализация оказывает и на идентичность, сложившуюся у конкретных этнических групп, наций и народов. В этой связи целесообразно перейти к рассмотрению сущно- стно-содержательной характеристики термина "идентичность", ее этнокультурному содержанию.

Е.П. Матузкова справедливо отмечает, что в объективной действительности культура реализуется в неразрывном взаимодействии двух форм ее бытия – объективной и субъективной [4, с. 63]. Такое сочетание обеспечивает ее идентичность и, следовательно, ее потребность в самосохранении в условиях преобразований в нор- мативно-ценностной и смысловой сферах. В таком ключе идентичность предстает как субстанциональная и относительно постоянная социальная ипостась – сфера действия закона культуросообразности конкретной общности, которая жизненно необходима в процессе ее устойчивого развития. То есть, можно говорить, что идентичность в данном понимании представляет собой некое культурное обобщение, формируемое каждой общностью в процессе генезиса и межкультурного общения.

Особый интерес вызывает точка зрения С. Солеймани, рассматривающая идентичность через призму культурной самотождественности. Автор обозначает идентичность как явление, которое вызывает у конкретного индивида и народа ощущение самотождественности [10, с.37]. Именно это ощущение позволяет определить индивиду и группе собственное положение в транснациональном пространстве. При этом для того, чтобы считать себя частью определенной группы, необходимы специальные составляющие. В качестве таких уникальных составляющих выступают следующие: язык; традиции; обычаи; народный фольклор и т.д.

Похожего мнения придерживаются И.К. Гончарова и Е.Ю. Липец, определяющие анализируемую дефиницию как причастность отдельного человека к культуре, которая формирует его ценностное ориентиры, допустимые нормы поведения, отношения к самому себе, обществу и миру [2, с. 14].

Интересно рассмотрение культурной идентичности с философской точки зрения. В данном контексте идентичность есть свойство бытия оставаться самим собой в непрерывно меняющихся и трансформирующихся объективных ситуациях.

Выработанная парадигма тяготеет к относительно устойчивому поведенческому равновесию общности и индивида, а подобную характеристику идентичности в науке принято обозначать термином «этничность».

До повсеместного распространения влияния глобализационных процессов этническая идентичность воспринималась людьми как некая данность, присущая им с момента их появления на свет. Это можно обосновать тем, что между географическим местоположением и этнокультурным опытом социума существовала автономная, достаточно прочная связь, которую разрушить было достаточно сложно. Это касалось преимущественно этнического наследия, которое передавалось из поколения в поколение в неизменном виде. То есть, можно сказать, что идентичность наряду с языком считаласьдостояниемколлективныхсообществ,проживающихнаконкретнойтерритории.

180