- •Для некоммерческого использования.

- •9. Fundamentals of English Lexicography:

- •§ 1. Definition. Links with

- •§ 2. Two Approaches to Language Study

- •§ 3. Lexicology and Sociolinguistics

- •§ 4. Lexical Units

- •§ 6. Course of Modern English

- •§ 2. Meaning in the Referential Approach

- •§ 3. Functional Approach to Meaning

- •§ 4. Relation between the Two Approaches

- •§ 5. Grammatical Meaning

- •§ 6. Lexical Meaning

- •§ 7. Parf-of-Speech Meaning

- •§ 8. Denotational and Connotational Meaning

- •§ 9. Emotive Charge

- •§ 10. Sfylistic Reference

- •§ 11. Emotive Charge and Stylistic Reference

- •§ 12. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 13. Lexical Meaning

- •§ 14. Functional (Parf-of-Speech) Meaning

- •§ 15. Differential Meaning

- •§ 16. Distributional Meaning

- •§ 17. Morphological Motivation

- •§ 18. Phonetical Motivation

- •§ 19. Semantic Motivation

- •§ 20. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 21. Causes of Semantic Change

- •§ 22. Nature of Semantic Change

- •§ 23. Results of Semantic Change

- •§ 24. Interrelation of

- •§ 25. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 26. Semantic Structure of Polysemantic Words

- •§ 27. Diachronic Approach

- •§ 28. Synchronic. Approach

- •§ 29. Historical

- •§ 30. Polysemy

- •§ 31. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 32. Homonymy of Words and Homonymy of Word-Forms

- •§ 33. Classification of Homonyms

- •§ 34. Some Peculiarities of Lexico-Grammatical Homonymy

- •§ 35. Graphic and Sound-Form of Homonyms

- •§ 36. Sources of Homonymy

- •§ 37. Polysemy and Homonymy:

- •§ 38. Formal Criteria: Distribution and Spelling

- •§ 39. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 40. Polysemy and Context

- •§ 41. Lexical Context

- •§ 42. Grammatical Context

- •§ 43. Extra-Linguistic Context (Context of Situation)

- •§ 44. Common Contextual

- •§ 45. Conceptual (or Semantic) Fields

- •§ 46. Hyponymic (Hierarchical) Structures and Lexico-Semantic Groups

- •§ 47. Semantic Equivalence and Synonymy

- •§ 49. Patterns of Synonymic Sets in Modern English

- •§ 50. Semantic Contrasts and Antonymy

- •§ 51. Semantic Similarity

- •§ 52. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Lexical Valency (Collocability)

- •§ 2. Grammatical Valency

- •§ 3. Distribution as the Criterion of Classification

- •§ 4. Lexical Meaning

- •§ 5. Structural Meaning

- •§ 6. Interrelation of Lexical

- •§ 7. Syntactic Structure

- •§ 8. Polysemantic and Monosemantic Patterns

- •§ 9. Motivation in Word-Groups

- •§ 10. Summary and Conclusions

- •§11. Free Word-Groups

- •§ 12. Criteria of Stability

- •§ 13. Classification

- •§ 14. Some Debatable Points

- •§ 15. Criterion of Function

- •§ 16. Phraseological Units and Idioms Proper

- •§ 17. Some Debatable Points

- •§ 18. Criterion of Context

- •§ 19. Some Debatable Points

- •§ 20. Phraseology as a Subsystem of Language

- •§ 21. Some Problems of the Diachronic Approach

- •§ 22. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Segmentation of Words into Morphemes

- •§ 2. Principles of Morphemic

- •§ 3. Classification of Morphemes

- •§ 4. Procedure of Morphemic Analysis

- •§ 5. Morphemic Types of Words

- •§ 6. Derivative Structure

- •§ 7. Derivative Relations

- •§ 8. Derivational Bases

- •§ 9. Derivational Affixes

- •§ 10. Semi-Affixes

- •§ 11. Derivational Patterns

- •§ 12. Derivational Types of Words

- •§ 13. Historical Changeability of Word-Structure

- •§ 14. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Various Types and Ways of Forming Words

- •§ 2. Word-Formation.

- •§ 3. Word-Formation as the Subject of Study

- •§ 4. Productivity of Word-Formation Means

- •§ 5. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 6. Definition. Degree

- •§ 7. Prefixation. Some Debatable Problems

- •§ 8. Classification of Prefixes

- •§ 9. Suffixation. Peculiarities of Some Suffixes

- •§ 10. Main Principles of Classification

- •§ 11. Polysemy and Homonymy

- •§ 12. Synonymy

- •§ 13. Productivity

- •§ 14. Origin of Derivational Affixes

- •§ 15. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 16. Definition

- •§ 17. Synchronic Approach

- •§ 18. Typical Semantic Relations

- •I. Verbs converted from nouns (denominal verbs).

- •II. Nouns converted from verbs (deverbal substantives).

- •§ 19. Basic Criteria of Semantic Derivation

- •§ 20. Diachronic Approach of Conversion. Origin

- •§ 21. Productivity.

- •§ 22. Conversion and Sound-(stress-) Interchange

- •1) Breath — to breathe

- •§ 23. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 24. Compounding

- •§ 25. Structure

- •§ 26. Meaning

- •§ 27. Structural Meaning of the Pattern

- •§ 28. The Meaning of Compounds. Motivation

- •§ 29. Classification

- •§ 30. Relations between the iCs of Compounds

- •§31. Different Parts of Speech

- •§ 32. Means of Composition

- •§ 33. Types of Bases

- •§ 34. Correlation between Compounds and Free Phrases

- •§ 35. Correlation Types of Compounds.

- •§ 36. Sources of Compounds

- •§ 37. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Some Basic Assumptions

- •§ 2. Semantic Characteristics and Collocability

- •§ 3. Derivational Potential

- •§ 4. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 5. Causes and Ways of Borrowing

- •§ 6. Criteria of Borrowings

- •§ 7. Assimilation of Borrowings

- •§ 8. Phonetic, Grammatical

- •§ 9. Degree of Assimilation and Factors Determining It

- •§ 10. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 11. The Role of Native and Borrowed Elements

- •§ 12. Influence of Borrowings

- •§ 13. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Notional and Form-Words

- •§ 2. Frequency, Polysemy and Structure

- •§ 3. Frequency and Stylistic Reference

- •§ 4. Frequency, Polysemy and Etymology

- •§ 5. Frequency and Semantic Structure

- •§ 6. Development of Vocabulary

- •§ 7. Structural and Semantic

- •§ 8. Productive Word-Formation

- •§ 9. Various Ways of Word-Creation

- •§ 10. Borrowing

- •§ 11. Semantic Extension

- •§ 12. Some Debatable Problems of Lexicology

- •§ 13. Intrinsic Heterogeneity of Modern English

- •§ 14. Number of Vocabulary

- •§ 15. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. General Characteristics

- •§ 2. Lexical Differences of Territorial Variants

- •§ 3. Some Points of History

- •§ 4. Local Dialects in the British Isles

- •§ 5. The Relationship Between

- •§ 6. Local Dialects in the usa

- •§ 7. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Encyclopaedic and Linguistic Dictionaries

- •§ 2. Classification of Linguistic Dictionaries

- •§ 3. Explanatory Dictionaries

- •§ 4. Translation Dictionaries

- •§ 5. Specialised Dictionaries

- •§ 6. The Selection

- •§ 7. Arrangement of Entries

- •§ 8. Selection and Arrangement of Meanings

- •§ 9. Definition of Meanings

- •§ 10. Illustrative Examples

- •§ 11. Choice of Adequate Equivalents

- •§ 12. Setting of the Entry

- •§ 13. Structure of the Dictionary

- •§ 14. Main Characteristic

- •§ 15. Classification of Learner’s Dictionaries

- •§ 16. Selection of Entry Words

- •§ 17. Presentation of Meanings

- •§ 18. Setting of the Entry

- •§ 19. Summary and Conclusions

- •§ 1. Contrastive Analysis

- •§ 2. Statistical Analysis

- •§ 3. Immediate Constituents Analysis

- •§ 4. Distributional Analysis and Co-occurrence

- •§ 5. Transformational Analysis

- •§ 6. Componental Analysis

- •§ 7. Method of Semantic Differential

- •§ 8. Summary and Conclusions

- •I. Introduction

- •II. Semasiology

- •Meaning and Polysemy

- •Polysemy and Homonymy

- •III. Word-groups and phraseological units

- •Interdependence of Structure and Meaning in Word-Groups

- •IV. Word-structure

- •V. Word-formation

- •Various Ways of Forming Words

- •Affixation

- •Word-Composition

- •VI. Etymological survey of the english word-stock

- •Words of Native Origin

- •Borrowings

- •Interrelation between Native and Borrowed Elements

- •VII. Various aspects of vocabulary units and replenishment of modern english word-stock

- •Interdependence of Various Aspects of the Word

- •Replenishment of Modern English Vocabulary

- •Ways and Means of Enriching the Vocabulary

- •VIII. Variants and dialects of the english language The Main Variants of the English Language

- •IX. Fundamentals of english lexicography Main Types of English Dictionaries

- •Some Basic Problems of Dictionary-Compiling

- •X. Methods and procedures of lexicological analysis

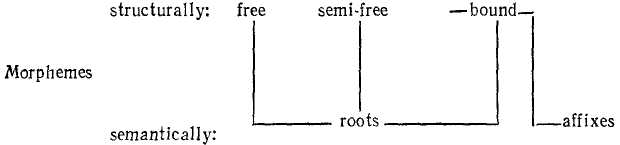

§ 3. Classification of Morphemes

Morphemes may be classified:

from the semantic point of view,

from the structural point of view.

a) Semantically morphemes fall into two classes: root-morphemes and non-root or affixational morphemes. Roots and affixes make two distinct classes of morphemes due to the different roles they play in word-structure.

Roots and affixational morphemes are generally easily distinguished and the difference between them is clearly felt as, e.g., in the words helpless, handy, blackness, Londoner, refill, etc.: the root-morphemes help-, hand-, black-, London-, -fill are understood as the lexical centres of the words, as the basic constituent part of a word without which the word is inconceivable.

The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of a ward, it has an individual lexical meaning shared by no other morpheme of the language. Besides it may also possess all other types of meaning proper to morphemes1 except the part-of-speech meaning which is not found in roots. The root-morpheme is isolated as the morpheme common to a set of words making up a word-cluster, for example the morpheme teach-in to teach, teacher, teaching, theor- in theory, theorist, theoretical, etc.

Non-root morphemes include inflectional morphemes or inflections and affixational morphemes or affixes. Inflections carry only grammatical meaning and are thus relevant only for the formation of word-forms, whereas affixes are relevant for building various types of stems — the part of a word that remains unchanged throughout its paradigm. Lexicology is concerned only with affixational morphemes.

Affixes are classified into prefixes and suffixes: a prefix precedes the root-morpheme, a suffix follows it. Affixes besides the meaning proper to root-morphemes possess the part-of-speech meaning and a generalised lexical meaning.

b) Structurally morphemes fall into three types: free morphemes, bound morphemes, semi-free (semi- bound) morphemes.

A free morpheme is defined as one that coincides with the stem 2 or a word-form. A great many root-morphemes are free morphemes, for example, the root-morpheme friend — of the noun friendship is naturally qualified as a free morpheme because it coincides with one of the forms of the noun friend.

A bound morpheme occurs only as a constituent part of a word. Affixes are, naturally, bound morphemes, for they always make part of a word, e.g. the suffixes -ness, -ship, -ise (-ize), etc., the prefixes un-,

1 See ‘Semasiology’, §§ 13-16, pp. 23-25. 2 See ‘Word-Structure’, § 8, p. 97.

92

dis-, de-, etc. (e.g. readiness, comradeship, to activise; unnatural, to displease, to decipher).

Many root-morphemes also belong to the class of bound morphemes which always occur in morphemic sequences, i.e. in combinations with ‘ roots or affixes. All unique roots and pseudo-roots are-bound morphemes. Such are the root-morphemes theor- in theory, theoretical, etc., barbar-in barbarism, barbarian, etc., -ceive in conceive, perceive, etc.

Semi-bound (semi-free) morphemes1 are morphemes that can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme. For example, the morpheme well and half on the one hand occur as free morphemes that coincide with the stem and the word-form in utterances like sleep well, half an hour,” on the other hand they occur as bound morphemes in words like well-known, half-eaten, half-done.

The relationship between the two classifications of morphemes discussed above can be graphically presented in the following diagram:

Speaking of word-structure on the morphemic level two groups of morphemes should be specially mentioned.

To the first group belong morphemes of Greek and Latin origin often called combining forms, e.g. telephone, telegraph, phonoscope, microscope, etc. The morphemes tele-, graph-, scope-, micro-, phone- are characterised by a definite lexical meaning and peculiar stylistic reference: tele- means ‘far’, graph- means ‘writing’, scope — ’seeing’, micro- implies smallness, phone- means ’sound.’ Comparing words with tele- as their first constituent, such as telegraph, telephone, telegram one may conclude that tele- is a prefix and graph-, phone-, gram-are root-morphemes. On the other hand, words like phonograph, seismograph, autograph may create the impression that the second morpheme graph is a suffix and the first — a root-morpheme. This undoubtedly would lead to the absurd conclusion that words of this group contain no root-morpheme and are composed of a suffix and a prefix which runs counter to the fundamental principle of word-structure. Therefore, there is only one solution to this problem; these morphemes are all bound root-morphemes of a special kind and such words belong to words made up of bound roots. The fact that these morphemes do not possess the part-of-speech meaning typical of affixational morphemes evidences their status as roots.2

1 The Russian term is относительно связанные (относительно свободные).

2 See ‘Semasiology’, §§ 15, 16, p. 24, 25.

93

The second group embraces morphemes occupying a kind of intermediate position, morphemes that are changing their class membership.

The root-morpheme man- found in numerous words like postman ['poustmэn], fisherman [fi∫эmэn], gentleman ['d3entlmэn] in comparison with the same root used in the words man-made ['mænmeid] and man-servant ['mæn,sэ:vэnt] is, as is well-known, pronounced, differently, the [æ] of the root-morpheme becomes [э] and sometimes disappears altogether. The phonetic reduction of the root vowel is obviously due to the decreasing semantic value of the morpheme and some linguists argue that in words like cabman, gentleman, chairman it is now felt as denoting an agent rather than a male adult, becoming synonymous with the agent suffix -er. However, we still recognise the identity of [man] in postman, cabman and [mæn] in man-made, man-servant. Abrasion has not yet completely disassociated the two, and we can hardly regard [man] as having completely lost the status of a root-morpheme. Besides it is impossible to say she is an Englishman (or a gentleman) and the lexical opposition of man and woman is still felt in most of these compounds (cf. though Madam Chairman in cases when a woman chairs a sitting and even all women are tradesmen). It follows from all this that the morpheme -man as the last component may be qualified as semi-free.