- •Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Contributors

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •1 Overview

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 The roots of English

- •1.3 Early history: immigration and invasion

- •1.4 Later history: internal migration, emigration, immigration again

- •1.5 The form of historical evidence

- •1.6 The surviving historical texts

- •1.7 Indirect evidence

- •1.8 Why does language change?

- •1.9 Recent and current change

- •2 Phonology and morphology

- •2.1 History, change and variation

- •2.2 The extent of change: ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ history

- •2.3 Tale’s end: a sketch of ModE phonology and morphology

- •2.3.1 Principles

- •2.3.2 ModE vowel inventories

- •2.3.3 ModE consonant inventories

- •2.3.4 Stress

- •2.3.5 Modern English morphology

- •2.4 Old English

- •2.4.1 Time, space and texts

- •2.4.2 The Old English vowels

- •2.4.3 The Old English consonants

- •2.4.4 Stress

- •2.4.5 Old English morphology

- •2.4.5.1 The noun phrase: noun, pronoun and adjective

- •2.4.5.2 The verb

- •2.4.6 Postlude as prelude

- •2.5 The ‘OE/ME transition’ to c.1150

- •2.5.1 The Great Hiatus

- •2.5.2 Phonology: major early changes

- •2.5.2.1 Early quantity adjustments

- •2.5.2.2 The old diphthongs, low vowels and /y( )/

- •2.5.2.3 The new ME diphthongs

- •2.5.2.4 Weak vowel mergers

- •2.5.2.5 The fricative voice contrast

- •2.6.1 The problem of ME spelling

- •2.6.2 Phonology

- •2.6.2.2 ‘Dropping aitches’ and postvocalic /x/

- •2.6.2.4 Stress

- •2.6.3 ME morphology

- •2.6.3.2 The morphology/phonology interaction

- •2.6.3.3 The noun phrase: gender, case and number

- •2.6.3.4 The personal pronoun

- •2.6.3.5 Verb morphology: introduction

- •2.6.3.6 The verb: tense marking

- •2.6.3.7 The verb: person and number

- •2.6.3.8 The verb ‘to be’

- •2.7.1 Introduction

- •2.7.2 Phonology: the Great Vowel Shift

- •2.7.4 English vowel phonology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.5 English consonant phonology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.5.1 Loss of postvocalic /r/

- •2.7.5.2 Palatals and palatalisation

- •2.7.5.3 The story of /x/

- •2.7.6 Stress

- •2.7.7 English morphology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.7.1 Nouns and adjectives

- •2.7.7.2 The personal pronouns

- •2.7.7.3 Pruning luxuriance: ‘anomalous verbs’

- •2.8.1 Preliminary note

- •2.8.2 Progress, regress, stasis and undecidability

- •2.8.2.1 The evolution of Lengthening I

- •2.8.2.2 Lengthening II

- •3 Syntax

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Internal syntax of the noun phrase

- •3.2.1 The head of the noun phrase

- •3.2.2 Determiners

- •3.3 The verbal group

- •3.3.1 Tense

- •3.3.2 Aspect

- •3.3.3 Mood

- •3.3.4 The story of the modals

- •3.3.5 Voice

- •3.3.6 Rise of do

- •3.3.7 Internal structure of the Aux phrase

- •3.4 Clausal constituents

- •3.4.1 Subjects

- •3.4.2 Objects

- •3.4.3 Impersonal constructions

- •3.4.4 Passive

- •3.4.5 Subordinate clauses

- •3.5 Word order

- •3.5.1 Introduction

- •3.5.2 Developments in the order of subject and verb

- •3.5.3 Developments in the order of object and verb

- •3.5.5 Developments in the position of particles and adverbs

- •3.5.6 Consequences

- •4 Vocabulary

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.1.1 The function of lexemes

- •4.1.3 Lexical change

- •4.1.4 Lexical structures

- •4.1.5 Principles of word formation

- •4.1.6 Change of meaning

- •4.2 Old English

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.4 Word formation

- •4.2.4.1 Noun compounds

- •4.2.4.2 Compound adjectives

- •4.2.4.3 Compound verbs

- •4.2.4.7 Zero derivation

- •4.2.4.8 Nominal derivatives

- •4.2.4.9 Adjectival derivatives

- •4.2.4.10 Verbal derivation

- •4.2.4.11 Adverbs

- •4.2.4.12 The typological status of Old English word formation

- •4.3 Middle English

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.2 Borrowing

- •4.3.2.1 Scandinavian

- •4.3.2.2 French

- •4.3.2.3 Latin

- •4.3.3 Word formation

- •4.3.3.1 Compounding

- •4.3.3.4 Zero derivation

- •4.4 Early Modern English

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Borrowing

- •4.4.2.1 Latin

- •4.4.2.2 French

- •4.4.2.3 Greek

- •4.4.2.4 Italian

- •4.4.2.5 Spanish

- •4.4.2.6 Other languages

- •4.4.3 Word formation

- •4.4.3.1 Compounding

- •4.5 Modern English

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Borrowing

- •4.5.3 Word formation

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •5 Standardisation

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 The rise and development of standard English

- •5.2.1 Selection

- •5.2.2 Acceptance

- •5.2.3 Diffusion

- •5.2.5 Elaboration of function

- •5.2.7 Prescription

- •5.2.8 Conclusion

- •5.3 A general and focussed language?

- •5.3.1 Introduction

- •5.3.2 Spelling

- •5.3.3 Grammar

- •5.3.4 Vocabulary

- •5.3.5 Registers

- •Electric phenomena of Tourmaline

- •5.3.6 Pronunciation

- •5.3.7 Conclusion

- •6 Names

- •6.1 Theoretical preliminaries

- •6.1.1 The status of proper names

- •6.1.2 Namables

- •6.1.3 Properhood and tropes

- •6.2 English onomastics

- •6.2.1 The discipline of English onomastics

- •6.2.2 Source materials for English onomastics

- •6.3 Personal names

- •6.3.1 Preliminaries

- •6.3.2 The earliest English personal names

- •6.3.3 The impact of the Norman Conquest

- •6.3.4 New names of the Renaissance and Reformation

- •6.3.5 The modern period

- •6.3.6 The most recent trends

- •6.3.7 Modern English-language personal names

- •6.4 Surnames

- •6.4.1 The origin of surnames

- •6.4.2 Some problems with surname interpretation

- •6.4.3 Types of surname

- •6.4.4 The linguistic structure of surnames

- •6.4.5 Other languages of English surnames

- •6.4.6 Surnaming since about 1500

- •6.5 Place-names

- •6.5.1 Preliminaries

- •6.5.2 The ethnic and linguistic context of English names

- •6.5.3 The explanation of place-names

- •6.5.4 English-language place-names

- •6.5.5 Place-names and urban history

- •6.5.6 Place-names in languages arriving after English

- •6.6 Conclusion

- •Appendix: abbreviations of English county-names

- •7 English in Britain

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Old English

- •7.3 Middle English

- •7.4 A Scottish interlude

- •7.5 Early Modern English

- •7.6 Modern English

- •7.7 Other dialects

- •8 English in North America

- •8.1.1 Explorers and settlers meet Native Americans

- •8.1.2 Maintenance and change

- •8.1.3 Waves of immigrant colonists

- •8.1.4 Character of colonial English

- •8.1.5 Regional origins of colonial English

- •8.1.6 Tracing linguistic features to Britain

- •8.2.2 Prescriptivism

- •8.2.3 Lexical borrowings

- •8.3.1 Syntactic patterns in American English and British English

- •8.3.2 Regional patterns in American English

- •8.3.3 Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE)

- •8.3.4 Atlas of North American English (ANAE)

- •8.3.5 Social dialects

- •8.3.5.1 Socioeconomic status

- •8.3.6 Ethnic dialects

- •8.3.6.1 African American English (AAE)

- •8.3.6.2 Latino English

- •8.3.7 English in Canada

- •8.3.8 Social meaning and attitudes

- •8.3.10 The future of North American dialects

- •Appendix: abbreviations of US state-names

- •9 English worldwide

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 The recency of world English

- •9.3 The reasons for the emergence of world English

- •9.3.1 Politics

- •9.3.2 Economics

- •9.3.3 The press

- •9.3.4 Advertising

- •9.3.5 Broadcasting

- •9.3.6 Motion pictures

- •9.3.7 Popular music

- •9.3.8 International travel and safety

- •9.3.9 Education

- •9.3.10 Communications

- •9.4 The future of English as a world language

- •9.5 An English family of languages?

- •Further reading

- •1 Overview

- •2 Phonology and morphology

- •3 Syntax

- •4 Vocabulary

- •5 Standardisation

- •6 Names

- •7 English in Britain

- •8 English in North America

- •9 English worldwide

- •References

- •Index

398 E D WA R D F I N E G A N

1999: 161). Use of modals also differs somewhat. In conversation, must, will, better and got to are less frequent than in BrE, whereas going to (or gonna) and have to (hafta) are more common than in BrE (Biber et al., 1999: 488). Except in some legal registers, the use of shall is diminishing drastically in NAE and BrE, probably more so in NAE.

NAE displays characteristic adverb use, as with the amplifier real, as in real good and real fast. At least in conversation, US residents prefer the amplifier pretty (pretty easy, pretty good) over quite (Biber et al., 1999: 567); quite as an amplifier (quite big, quite easy) occurs in NAE only one-seventh as often as in BrE. Both varieties use quite and pretty with the adjectives sure and good, but AmE tends to limit quite sure to negative contexts: not/never quite sure. Now and immediately function as adverbs but not conjunctions in NAE, and to make these examples from the BNC grammatical in NAE, the underscored subordinators have been added: Now that they’re older they can do it and They took off immediately after the passengers were on board.

With noun phrases that denote a point in space or time, NAE sometimes requires an article where BrE does not: in the hospital and the next day. In some expressions, both varieties omit the article for relatively general senses of the noun: in school, to class, in college, to church.

In NAE the preposition may be omitted from certain time references and after certain verbs, as in a doctor’s appointment Monday; see you this weekend; and departed New York on time (cf. on Monday, at the weekend, from New York). Preposition choice or form may differ: a store on Main Street (cf. a shop in the High Street), different than or different from (different to), around the city (round) and toward the light (towards).

8.3.2 |

Regional patterns in American English |

|

A picture of North American dialects, particularly in the eastern US, has been available since the mid-twentieth century, but our understanding is complicated by the vast geographical expanse of the country and the fact that several areas west of the Mississippi River remain to be adequately investigated, and existing surveys employed different techniques and were carried out at different times; in addition, some studies focussed on pronunciation, others on vocabulary. While the general processes that establish dialects are similar for diverse kinds of features, distributions of phonological and lexical variants seldom coincide. Indeed, distributions for any two lexical items seldom coincide. In addition, much of what was investigated earlier characterised rural speakers, while later sociolinguistic interest preferred urban speakers. Finally, especially the western states and provinces continue to develop with in-migration and immigration, so dialect patterns remain unsettled.

Regional atlases have been completed for New England (Kurath et al., 1939– 43), the Upper Midwest (Allen, 1973–6), and the Gulf States (Pederson et al., 1986–93). For some other regions (North Central States, Middle and South

English in North America |

399 |

Atlantic States, Pacific West), fieldwork has been completed and some findings published. (For current information about regional atlases, see the Linguistic Atlas Projects website < http://us.english.uga.edu/ >.) A widely, but not universally, accepted view is that American English has four main regional dialects (North, Midland, South, and West), each with subdivisions, twenty-one in all, as listed in Pederson’s (2001) thorough overview. With its settlement history across a great expanse, the US has a complex pattern of regional dialects, with some broad strokes differentiating regions essentially from east to west, but with subdivisions within those dialects. Features of several regions have been mentioned above, although regions are best described in terms of sets of features rather than uniquely characteristic ones.

North American English, as we have seen, has several sources: the English brought from England to the New World by the original colonists; the English brought by later immigrants from England and other parts of Britain and Ireland; innovation in North America; and borrowings from Native Americans and from immigrant groups speaking other languages. But agreement diminishes in tracing particular expressions, grammatical forms and pronunciations, particularly to their British sources. Krapp (1925) and Kurath (1949; Kurath & McDavid, 1961) underscored the links between AmE and the standard English of southeast England, and many dialect maps in The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States

(Kurath & McDavid, 1961) contain insets of the southeastern counties of England with pronunciations matching those along the American seaboard. More generally, these interpretive studies tend to discount the likelihood of regional features of British or Irish English surviving in American regional dialects. Commenting, for example, on South and South Midland pronunciations of because with [e] in the second syllable, Kurath & McDavid (1961: 162) report ‘no evidence’ for the phenomenon in English dialects, but Montgomery (2001: 139) identifies the pronunciation in Ulster dialects and on that basis and others objects to their claim that ‘distinctive features of the dialects of the northern counties of England, of Scotland, and of Northern Ireland rarely survive in American English’.

8.3.3 |

Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) |

|

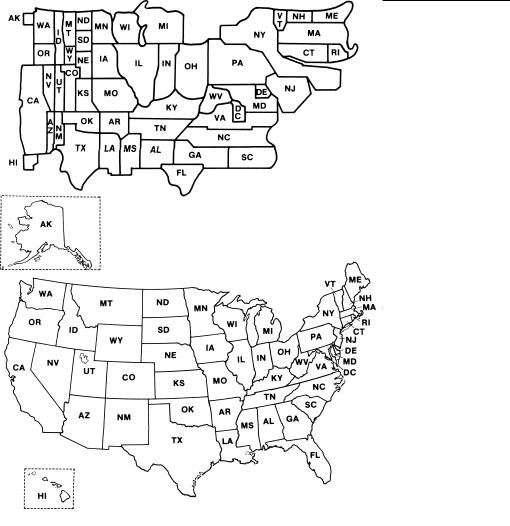

Besides the regional atlases, a promising tool for addressing regional associations between NAE and Britain is the Dictionary of American Regional English. DARE treats regional words and expressions and displays many findings on maps that represent population distribution rather than strict geographical boundaries and thus shape state borders and state sizes only roughly as compared to a traditional map. A DARE map encloses a grid of the 1,002 communities canvassed in its 1960s survey. If a particular variant occurred in a community, a filled circle appears on the map for that feature in that community; if not, the space designating that community remains empty. For a feature used in every community, the map would contain no empty spaces. Figure 8.1 shows a DARE map and a traditional map of the United States. (Full names for abbreviations

400 E D WA R D F I N E G A N

Figure 8.1 DARE map and conventional map, with state names

Source: Dictionary of American Regional English, I, 1985

such as ME ‘Maine’ and MN ‘Minnesota’ can be found in the Appendix to this chapter.)

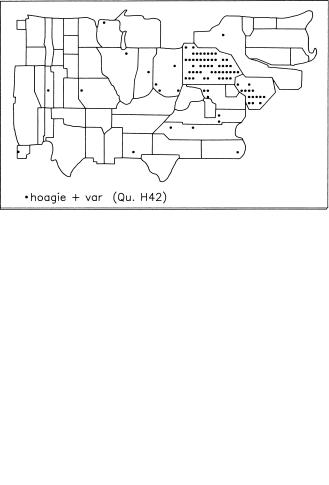

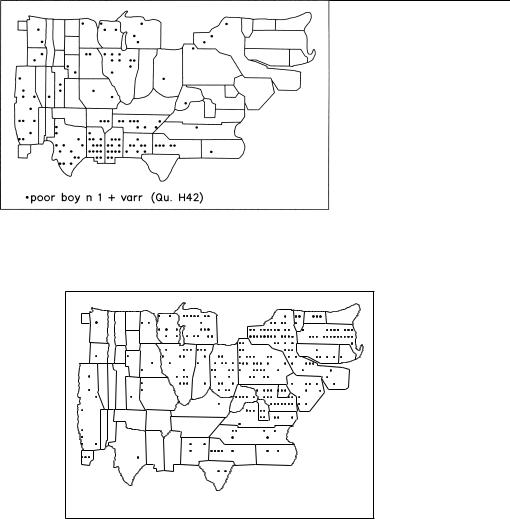

We illustrate DARE’s treatment with regional terms for a long sandwich made on an Italian roll or French bread. Hero (shortened from hero sandwich) is common in Metropolitan New York City, with some use in nearby New Jersey and upstate New York, but only sporadic use elsewhere (Figure 8.2). Hoagie is the term used almost exclusively in Pennsylvania and New Jersey (Figure 8.3). Poor boy, commonly pronounced ‘po’boy’ or ‘pore boy’, originated in Louisiana and spread west into Texas and California, east into Mississippi and Alabama, and northeast into Tennessee; a few communities in northern Illinois also used poor

English in North America |

401 |

Figure 8.2 Distribution of hero on a DARE map

Source: Dictionary of American Regional English, II, 1991

Figure 8.3 Distribution of hoagie on a DARE map

Source: Dictionary of American Regional English, II, 1991

boy, but most states show no occurrences (Figure 8.4). Submarine sandwich (Figure 8.5) appears mostly in the north central and northeast states, although the distribution of submarine and sub is likely to be far more widespread than that represented in Figure 8.5 because in 1965 the popular ‘Subway’ chain of fastfood restaurants was launched. Besides these terms, grinder is the preferred name in New England (except for Maine), while Cuban sandwich is used in Miami, Florida.

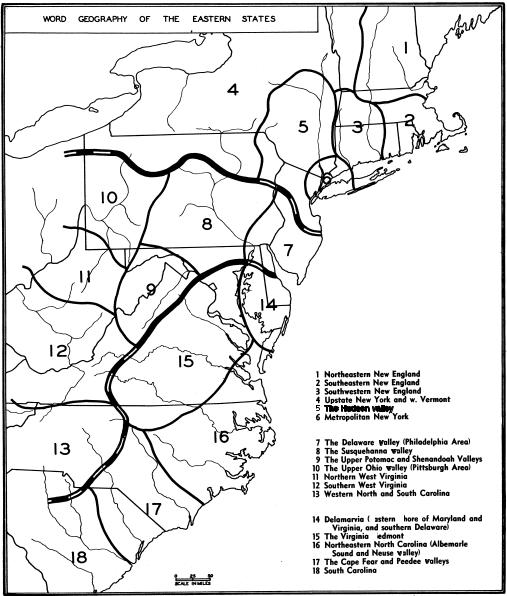

From DARE’s findings, a map of American dialects has been proposed, as we will see. First, we describe the traditional method for determining dialect boundaries by plotting occurrences of a single feature on a map and drawing isoglosses at the boundary delimiting occurrences of the feature. Reflecting this method, maps in Word Geography of the Eastern United States (Kurath, 1949)

402 E D WA R D F I N E G A N

Figure 8.4 Distribution of poor boy on a DARE map

Source: Dictionary of American Regional English, IV, 2002

.submarine sandwich + varr (Qq. H42, H41)

Figure 8.5 Distribution of submarine sandwich on a DARE map

Source: Dictionary of American Regional English, V, forthcoming

show the distribution of variants of a linguistic feature on a traditional map. Dialect maps are then drawn, in effect, by overlaying several maps to reveal bundles of isoglosses. Where isoglosses bundle together, dialect boundaries are proposed, such as those in Figure 8.6. Kurath’s map of the eastern US depicts three main dialects – North, Midland and South – a word-based division used later again when Kurath laid out regional patterns of pronunciation, despite his recognising and acknowledging noticeable differences between word boundaries and pronunciation boundaries.

Taking a different approach and using DARE materials, Carver (1987) relied on the number of isoglosses shared by a community to create ‘layers’ that enabled him to identify stronger and weaker dialect boundaries. He proposed a new dialect map

English in North America |

403 |

The speech areas of the eastern states

The north

The midland

The south

e s

p

Figure 8.6 Kurath’s dialect regions of the eastern states, based on vocabulary

Source: Kurath, 1949

that generally resembles earlier maps, but postulates only two major US dialects – North and South – each with upper and lower sections and each with subsections (see Figure 8.7). He also identified a weaker West dialect, an extension largely of the North, and argued that the traditional division into Northern, Midland and Southern dialects overlooked a fundamental divide between North and South.