- •Contents

- •Figures

- •Tables

- •Contributors

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •1 Overview

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 The roots of English

- •1.3 Early history: immigration and invasion

- •1.4 Later history: internal migration, emigration, immigration again

- •1.5 The form of historical evidence

- •1.6 The surviving historical texts

- •1.7 Indirect evidence

- •1.8 Why does language change?

- •1.9 Recent and current change

- •2 Phonology and morphology

- •2.1 History, change and variation

- •2.2 The extent of change: ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ history

- •2.3 Tale’s end: a sketch of ModE phonology and morphology

- •2.3.1 Principles

- •2.3.2 ModE vowel inventories

- •2.3.3 ModE consonant inventories

- •2.3.4 Stress

- •2.3.5 Modern English morphology

- •2.4 Old English

- •2.4.1 Time, space and texts

- •2.4.2 The Old English vowels

- •2.4.3 The Old English consonants

- •2.4.4 Stress

- •2.4.5 Old English morphology

- •2.4.5.1 The noun phrase: noun, pronoun and adjective

- •2.4.5.2 The verb

- •2.4.6 Postlude as prelude

- •2.5 The ‘OE/ME transition’ to c.1150

- •2.5.1 The Great Hiatus

- •2.5.2 Phonology: major early changes

- •2.5.2.1 Early quantity adjustments

- •2.5.2.2 The old diphthongs, low vowels and /y( )/

- •2.5.2.3 The new ME diphthongs

- •2.5.2.4 Weak vowel mergers

- •2.5.2.5 The fricative voice contrast

- •2.6.1 The problem of ME spelling

- •2.6.2 Phonology

- •2.6.2.2 ‘Dropping aitches’ and postvocalic /x/

- •2.6.2.4 Stress

- •2.6.3 ME morphology

- •2.6.3.2 The morphology/phonology interaction

- •2.6.3.3 The noun phrase: gender, case and number

- •2.6.3.4 The personal pronoun

- •2.6.3.5 Verb morphology: introduction

- •2.6.3.6 The verb: tense marking

- •2.6.3.7 The verb: person and number

- •2.6.3.8 The verb ‘to be’

- •2.7.1 Introduction

- •2.7.2 Phonology: the Great Vowel Shift

- •2.7.4 English vowel phonology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.5 English consonant phonology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.5.1 Loss of postvocalic /r/

- •2.7.5.2 Palatals and palatalisation

- •2.7.5.3 The story of /x/

- •2.7.6 Stress

- •2.7.7 English morphology, c.1550–1800

- •2.7.7.1 Nouns and adjectives

- •2.7.7.2 The personal pronouns

- •2.7.7.3 Pruning luxuriance: ‘anomalous verbs’

- •2.8.1 Preliminary note

- •2.8.2 Progress, regress, stasis and undecidability

- •2.8.2.1 The evolution of Lengthening I

- •2.8.2.2 Lengthening II

- •3 Syntax

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Internal syntax of the noun phrase

- •3.2.1 The head of the noun phrase

- •3.2.2 Determiners

- •3.3 The verbal group

- •3.3.1 Tense

- •3.3.2 Aspect

- •3.3.3 Mood

- •3.3.4 The story of the modals

- •3.3.5 Voice

- •3.3.6 Rise of do

- •3.3.7 Internal structure of the Aux phrase

- •3.4 Clausal constituents

- •3.4.1 Subjects

- •3.4.2 Objects

- •3.4.3 Impersonal constructions

- •3.4.4 Passive

- •3.4.5 Subordinate clauses

- •3.5 Word order

- •3.5.1 Introduction

- •3.5.2 Developments in the order of subject and verb

- •3.5.3 Developments in the order of object and verb

- •3.5.5 Developments in the position of particles and adverbs

- •3.5.6 Consequences

- •4 Vocabulary

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.1.1 The function of lexemes

- •4.1.3 Lexical change

- •4.1.4 Lexical structures

- •4.1.5 Principles of word formation

- •4.1.6 Change of meaning

- •4.2 Old English

- •4.2.1 Introduction

- •4.2.4 Word formation

- •4.2.4.1 Noun compounds

- •4.2.4.2 Compound adjectives

- •4.2.4.3 Compound verbs

- •4.2.4.7 Zero derivation

- •4.2.4.8 Nominal derivatives

- •4.2.4.9 Adjectival derivatives

- •4.2.4.10 Verbal derivation

- •4.2.4.11 Adverbs

- •4.2.4.12 The typological status of Old English word formation

- •4.3 Middle English

- •4.3.1 Introduction

- •4.3.2 Borrowing

- •4.3.2.1 Scandinavian

- •4.3.2.2 French

- •4.3.2.3 Latin

- •4.3.3 Word formation

- •4.3.3.1 Compounding

- •4.3.3.4 Zero derivation

- •4.4 Early Modern English

- •4.4.1 Introduction

- •4.4.2 Borrowing

- •4.4.2.1 Latin

- •4.4.2.2 French

- •4.4.2.3 Greek

- •4.4.2.4 Italian

- •4.4.2.5 Spanish

- •4.4.2.6 Other languages

- •4.4.3 Word formation

- •4.4.3.1 Compounding

- •4.5 Modern English

- •4.5.1 Introduction

- •4.5.2 Borrowing

- •4.5.3 Word formation

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •5 Standardisation

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 The rise and development of standard English

- •5.2.1 Selection

- •5.2.2 Acceptance

- •5.2.3 Diffusion

- •5.2.5 Elaboration of function

- •5.2.7 Prescription

- •5.2.8 Conclusion

- •5.3 A general and focussed language?

- •5.3.1 Introduction

- •5.3.2 Spelling

- •5.3.3 Grammar

- •5.3.4 Vocabulary

- •5.3.5 Registers

- •Electric phenomena of Tourmaline

- •5.3.6 Pronunciation

- •5.3.7 Conclusion

- •6 Names

- •6.1 Theoretical preliminaries

- •6.1.1 The status of proper names

- •6.1.2 Namables

- •6.1.3 Properhood and tropes

- •6.2 English onomastics

- •6.2.1 The discipline of English onomastics

- •6.2.2 Source materials for English onomastics

- •6.3 Personal names

- •6.3.1 Preliminaries

- •6.3.2 The earliest English personal names

- •6.3.3 The impact of the Norman Conquest

- •6.3.4 New names of the Renaissance and Reformation

- •6.3.5 The modern period

- •6.3.6 The most recent trends

- •6.3.7 Modern English-language personal names

- •6.4 Surnames

- •6.4.1 The origin of surnames

- •6.4.2 Some problems with surname interpretation

- •6.4.3 Types of surname

- •6.4.4 The linguistic structure of surnames

- •6.4.5 Other languages of English surnames

- •6.4.6 Surnaming since about 1500

- •6.5 Place-names

- •6.5.1 Preliminaries

- •6.5.2 The ethnic and linguistic context of English names

- •6.5.3 The explanation of place-names

- •6.5.4 English-language place-names

- •6.5.5 Place-names and urban history

- •6.5.6 Place-names in languages arriving after English

- •6.6 Conclusion

- •Appendix: abbreviations of English county-names

- •7 English in Britain

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Old English

- •7.3 Middle English

- •7.4 A Scottish interlude

- •7.5 Early Modern English

- •7.6 Modern English

- •7.7 Other dialects

- •8 English in North America

- •8.1.1 Explorers and settlers meet Native Americans

- •8.1.2 Maintenance and change

- •8.1.3 Waves of immigrant colonists

- •8.1.4 Character of colonial English

- •8.1.5 Regional origins of colonial English

- •8.1.6 Tracing linguistic features to Britain

- •8.2.2 Prescriptivism

- •8.2.3 Lexical borrowings

- •8.3.1 Syntactic patterns in American English and British English

- •8.3.2 Regional patterns in American English

- •8.3.3 Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE)

- •8.3.4 Atlas of North American English (ANAE)

- •8.3.5 Social dialects

- •8.3.5.1 Socioeconomic status

- •8.3.6 Ethnic dialects

- •8.3.6.1 African American English (AAE)

- •8.3.6.2 Latino English

- •8.3.7 English in Canada

- •8.3.8 Social meaning and attitudes

- •8.3.10 The future of North American dialects

- •Appendix: abbreviations of US state-names

- •9 English worldwide

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 The recency of world English

- •9.3 The reasons for the emergence of world English

- •9.3.1 Politics

- •9.3.2 Economics

- •9.3.3 The press

- •9.3.4 Advertising

- •9.3.5 Broadcasting

- •9.3.6 Motion pictures

- •9.3.7 Popular music

- •9.3.8 International travel and safety

- •9.3.9 Education

- •9.3.10 Communications

- •9.4 The future of English as a world language

- •9.5 An English family of languages?

- •Further reading

- •1 Overview

- •2 Phonology and morphology

- •3 Syntax

- •4 Vocabulary

- •5 Standardisation

- •6 Names

- •7 English in Britain

- •8 English in North America

- •9 English worldwide

- •References

- •Index

370 R I C H A R D H O G G

Most northern English dialects of PDE lack the phoneme / /. This phoneme arose with the split of ME phoneme /υ/, so that standard English contrasts foot /fυt/ and strut /str t/. The first direct evidence for the split comes in 1640 (for this and other phonological evidence during the period, Dobson, 1957, is essential and invaluable). Interestingly, already in 1596, Edmund Coote, the author of The English Schoole-Master (see Dobson, 1957: 33), had detected the split. Coote, based in Suffolk, objects to ‘the barbarous speech of your country people’, but for us this may be an indication of an East Anglian source

for the split.

A particularly salient variation results from the early Modern English change by which /a/ is lengthened before voiceless fricatives. This lengthening produces standard English forms such as /lɑ f/, /bɑθ/, /pɑ st/ for laugh, bath, past. Although the evolution of such forms is in fact lengthy, so that the position is by no means stable even today, it is worth noting the situation here, since it was in the early Modern English period that the contrasts came to be established. The bestknown dialectal variation is that almost all northern dialects have /baθ/, etc. in all these words. But there are variations too. For example, many midlands dialects show lengthening but not retraction, i.e. /baθ/, and over many southern areas raising to /æ / is common and can equally

affect the vowel of cat to give /kæt/.

In many west midlands and northwestern dialects the final /g/ in words such as thing is retained, i.e. /θ ŋg/ against standard /θ ŋ/. The standard loss of final /g/ is observable from the end of the sixteenth century but

that appears to be the result of earlier loss in East Anglia and Essex.

One interesting change which is to some extent a conservative throwback associated with the Great Vowel Shift is the preservation of the distinction between /i / and /e / (from ME /e / and / /) in meet and meat. As discussed elsewhere, in the standard language these vowels merged during the eighteenth century, but some dialects preserved the distinction. This is true of parts of the north and also of Ireland; see further below. But the distinction has been receding everywhere and may soon be lost completely.

7.6Modern English

If the Middle English period can be described as the age of dialects, then a parallel description of the Modern English period would be as the period of dialectology. The aptness of such a description is based on many different features. And it seems appropriate to consider some of these here. The reason for this is that it is only through a discussion of the basics of the development

English in Britain |

371 |

of dialectological theory that we can hope to reach an understanding of how the attitudes to and the treatment of dialects has evolved.

Although grammarians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often discuss non-standard forms, their principal reason for so doing was almost always from the vantage point of standard English and their aim to guide their readers away from social misfortune; see, for example, Mugglestone (2003). When dialect collections first appear – and perhaps the first important such collection is by John Ray in 1674 with a second edition in 1691 – the interest is primarily in vocabulary. In terms of dialect mapping, Ray classifies forms largely by county, which is a common feature of later studies too. But Ihalainen (1994) suggests that Ray probably considered there to be a north–south divide with that division roughly along a line from Bristol to the Wash, not a division which would seem sensible to later dialectologists. Ihalainen (1994) also provides a useful overview of later eighteenthand nineteenth-century dialect collections, culminating, perhaps, in Halliwell’s Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words, first published in 1847.

But, as Ihalainen also says, there was until the last quarter of the nineteenth century no serious attempt to present a coherent picture of the contemporary dialect situation. There is no single reason why the situation should have changed then, but rather a multiplicity of reasons. Clearly the ever growing urbanisation of England created an emerging polarity between standard English and local urban dialects. As Sweet (1890) writes: ‘The Cockney dialect seems very ugly to an Englishman or woman because he – and still more she – lives in perpetual terror of being taken for a Cockney . . .’ And many dialectologists complained about the way in which the railways were destroying local dialects, in terms rather reminiscent of Wordsworth’s fears for the Lake District in the age of steam.

But there was also a purely linguistic factor involved. For this was the time of both the Neogrammarian movement, which spread out from Leipzig, and of the first systematic attempts at dialect geography, in particular the German atlas started by Georg Wenkler in 1876, almost simultaneous with the birth of Neogrammarianism. In Britain this burst of activity was evident in both the Philological Society and the English Dialect Society. Thus in 1875, Alexander Ellis, with the assistance of others, produced a classification of English dialects which remains important today; see Ellis (1875) and also Ihalainen (1994) for detailed discussion; Trudgill (1999b) offers a brief introduction to the distinctions between presentday dialects and those in the Survey of English Dialects (SED), that is, the dialect situation at the end of the nineteenth century.

In 1889 Ellis produced what is generally recognised as the first systematic survey of English dialects (Ellis, 1889). Alongside this work, there began to appear the first systematic studies on individual dialects, of which Elworthy’s study of the dialect of West Somerset (1875) is a notable example. Even more interesting was the study of the dialect of Windhill in Yorkshire, published by Joseph Wright in 1892. Wright was not only a native of Windhill, a manufacturing township now

372 R I C H A R D H O G G

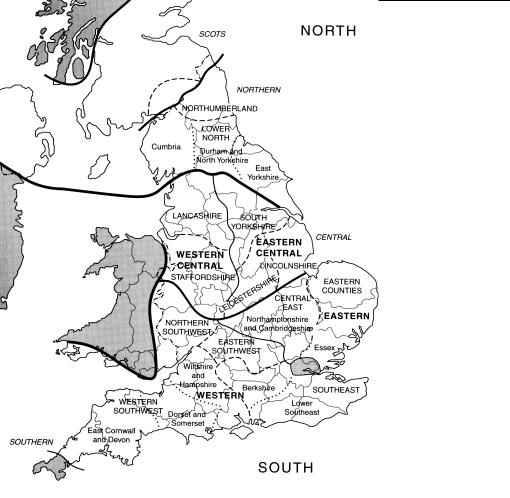

Figure 7.3 Traditional dialect areas (Trudgill, 1999b)

part of the Leeds–Bradford conurbation, but he was to become both Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford and editor of the English Dialect Dictionary (Wright, 1898–1905). This latter work retains its interest today, not merely as a fund of information, although it is that. The production of the EDD was contemporary with the production of the OED and indeed the EDD was intended as an adjunct to the OED. As such, it attempted to replicate features of the OED, such as using only written citations. From our point of view today, this is unfortunate, but the temper of the times was very different from that to which we are used.

Unlike the position in Germany and France, and indeed several other continental countries, it was a remarkably long time before a full-scale dialect atlas of either England or Scotland was produced. In Britain we had to wait until 1948, when Harold Orton, of the University of Leeds, together with Eugen Dieth of

English in Britain |

373 |

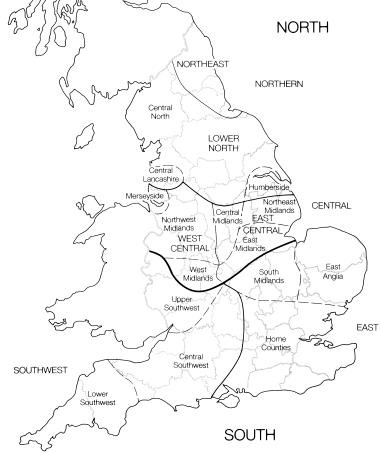

Figure 7.4 Modern dialect areas (Trudgill, 1999b)

Zurich, started work on the Survey of English Dialects (SED), which was eventually published in 1962–71 (Orton et al., 1962–71).

It is worth spending some time on the SED, since it is the essential tool for the study of traditional dialectology in Britain (although it is in fact exclusively English). The SED proceeded by means of directly interviewing dialect speakers from some 313 different localities in England, usually, but not always, one single informant from each locality. But these bare facts tell us very little. It is important to understand exactly what the aims of this study were, and to recall that it was only recently that mobile recording equipment had become easily available and also acceptable to untutored informants. Thus, above all, the SED strove to gather information about rural dialects which, it was felt, were fast disappearing under the pressures of urbanisation.

This meant that the SED was interested primarily in speakers who met four criteria: they had to be non-mobile, old, rural and male. Nowadays this group is colloquially referred to by the acronym NORMS. Each term had its own

374 R I C H A R D H O G G

justification. Informants should be non-mobile, so that they had not been subject to interference from another dialect, i.e. they spoke the ‘pure’ dialect of their native locality. They had to be old, because the aim was to record the speech of about fifty years previous, i.e. the speech of approximately the beginning of the twentieth century. I have already explained the motivation for choosing rural speakers. Males were preferred over females because it was thought that females were more subject to pressure from standardised forms of the language. In hindsight we might well regret some of the decisions that were made about informants, but whatever the case might be (at least the decision to interview only older speakers seems absolutely right under the circumstances), we have to accept those decisions as a fact of life.

One feature which at first sight most surprises present-day readers of the SED is the small number of informants. The number appears equally small when compared with the number of speakers used in the German and French dialect atlases compiled at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the next; see here Chambers & Trudgill (1980: 18ff.) for a comparative view. But there is a good explanation for the small number. The SED was organised on the basis of a set questionnaire with a variety of questions, often to be presented in an indirect manner, so that we find questions such as:

What’s in my pocket? [show an empty pocket] (nothing, nought)

Given that in total there were approximately 1,200 questions, all formed in the same manner, and that those questions were required to be asked in a set order, this took about 20 to 24 hours to administer, and often one informant would be replaced by another in order to complete the task – it should be recalled that informants were generally quite old and relatively uneducated.

What the SED provides us with, therefore, is a snapshot of a relatively stable, agriculturally based male community whose members were born around the beginning of the twentieth century. The mass of material which was collected has made it possible to produce a range of maps, in particular maps demonstrating the variety in both the phonological systems and the vocabulary. The two essential texts published by the SED are The Linguistic Atlas of England (LAE) (Orton et al., 1978) and A Word Geography of England (Orton & Wright, 1974); see also the Further Reading to this chapter. It must be pointed out that it requires some sophistication in order to read such works as the LAE successfully; and the mapping of isoglosses to distinguish the spread of individual items is a major interpretive task. For some of the pitfalls see the very useful remarks in Francis (1983).

If we look at the dialect situation in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, when dialect studies first began to flourish and only a few decades before SED informants were born, we find that in many aspects of the language there remained features which we might regard today as not merely dialectal, but frankly archaic. Below I list a few examples from the SED material which may help to make readers aware of what has now gone, or almost gone, from the language. This list is, of course, at one and the same time, selective and random.

English in Britain |

375 |

In vocabulary, it is doubtful, for example, that tab ‘ear’ is any longer found in Nottinghamshire or Derbyshire, and lug, instead of being found widely through out the north and east, as far south as Suffolk, is certainly becoming more recessive as ear becomes the ‘normal’ word in so much more of the country (although it remains a possibility for a Scot like me). Other words which have been lost or are almost lost include: urchin ‘hedgehog’ (northern, also Shropshire, Herefordshire); mind ‘remember’ is still common in Scotland, but pockets of mind formerly throughout England have lost out except perhaps on the Scottish border; quist ‘pigeons’ was formerly found in the west midlands from Cheshire to Gloucestershire, but is certainly not found in Cheshire today. It would be wrong, however, to suggest that all dialect vocabulary has been lost. For example, my own experience would suggest that lake ‘play’ is still possible in many parts of Yorkshire.

If the above paragraph gives only a tantalising flavour, it is perhaps easier to list significant morphological features. Here I concentrate on aspects of the pronoun system. One important feature which still obtained quite frequently in mid-nineteenth-century local dialects was the preservation of the second-person singular pronoun thou, which persisted widely throughout the north and the west, but was always threatened by you, a process which today is almost complete although it remains in the speech of at least some speakers from Yorkshire. That is by no means the only change in the pronoun system. Throughout the south midlands, from Leicestershire to Hampshire his and hers at the time of the SED retained the old Middle English midlands forms hisn, hern, whilst hissen for himself is still found in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, but hissel, the form still found quite widely at that time, is probably receding except in Scotland and the northernmost parts of England.

Let us now turn our attention to syntax, which is often regarded as the cinderella of dialect studies. One reason for this is that both vocabulary and phonology provide an easier and almost immediate reaction. If I were to use the word gallus, for example (which happens to be part of my native vocabulary), I doubt if more than 10 per cent of the British population would know what I meant. Native speakers of British English can normally detect phonological features in dialects other than their own without much difficulty. But often syntactic features are either unnoticed or dismissed as errors, rather than genuine dialectal variations.

Here I want to consider a small group of historical syntactic features, which are sometimes near to extinction, although they seem to have been quite vigorous 150 years ago, others of which remain viable and sometimes strong. The first of these is found in northern dialects, and is called ‘The Northern subject rule’; see Ihalainen (1994: 221–2), also Chapman (1998). The following are typical examples:

They peel them and boils them

Him and me drinks nought but water

I often tells him

I tell him not to

376 R I C H A R D H O G G

The general rule in this construction is that inflectional -s is found throughout the present tense, unless the verb is immediately preceded or followed by a single personal pronoun subject. Thus there is both an extension of the inflection, and it is nevertheless absent in the immediate vicinity of a personal pronoun. This feature is one which already existed in sixteenth-century northern English and Scots. William Dunbar writes:

On to the ded gois all Estatis

Although the dialectal spread of the Northern subject rule may have shrunk a little over the intervening time, it is still alive and well in its core areas. A superficially similar morphology occurs in East Anglian dialects, where there is no inflection throughout the present, so that we find:

She like him

but this is simply total loss of the inflection. This too appears to remain fully viable, although it has retreated from Essex, where it was formerly strong; see Trudgill (1999b: 101–2).

Southwestern and west midlands dialects have a peculiar feature no longer found elsewhere. This is a process called Pronoun Exchange, and produces sentences such as:

Her told I

which actually means ‘She told him.’ But as Trudgill (1999b: 95–8) observes, this feature was also found in Essex in the nineteenth century, which leads him to suppose, plausibly, that it was formerly a quite widespread feature of southern and western dialects before receding under the influence of the standard language. Another southern feature which was already almost lost by the twentieth century is the pronoun Ich ‘I’, as in the phrase Chill let you go in King Lear. Alexander Ellis (1889) talks of part of Somerset as The Land of Utch. It seems to have survived, just, into the 1970s.

So far I have not touched on pronunciation, yet this is perhaps the area where change is most obvious and salient. This omission has been deliberate. For this area has some interesting features, which means that it requires rather different treatment. Of course, most of the emphasis of dialect study has been placed on the phonological material, for reasons that we have already mentioned. As a result, there is a huge amount of material which we could consider, greatly exceeding the bounds of this chapter. But there is a rather more interesting issue. It seems quite clear that the last two hundred years has seen a considerable amount of change in pronunciation; see MacMahon (1998: esp. 373–4). MacMahon is talking about standard English; but the changes in non-standard dialects are even greater. The changes which have occurred in dialects over the last two hundred years, and which are most apparent in the area of phonology, can be classified into three types: (1) standardisation; (2) levelling; (3) innovation. Let us examine each these in turn, starting with standardisation.

English in Britain |

377 |

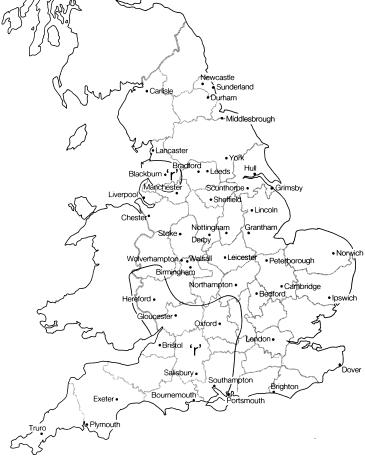

Figure 7.5 Limits of postvocalic /r/ in present-day dialects (from Trudgill, 1999b)

Most ordinary people have the perception that local dialects are disappearing under the pressure of standardisation, the result of a variety of factors, amongst which the rise of literacy due to increased education is perhaps the most obvious. To this must be added other elements such as the rise of mass media (as much the result of mass literacy as anything else) and the continuous urbanisation of the country. And that is indeed true, although, as we shall see, there are counter-effects which mean that the situation is not quite so simple.

Nevertheless, the effects of standardisation can be very well exemplified by considering one of the most notable features of standard English English, namely the loss of postvocalic /r/ in words such as arm (/ɑ m/). This is in striking contrast to the preservation of /r/ in both Scottish English and American English. It is also in contrast to the dialect situation about 100 years ago. For then, all dialects south of a line from Shrewsbury to Dover (but, importantly, excluding London) where equally rhotic, as was the northwest (from Chester northwards) and also the Tyneside area.

378 R I C H A R D H O G G

But ever since then the rhotic area has shrunk, so that now only the area southwest of a line from Northampton to Portsmouth and a small enclave centred on Blackburn in Lancashire remain. And everywhere on the margins of these areas, especially those closest to London, the rhotic forms are predominantly found with older speakers only. Other features show a similarly recessive character. Even the northern and midlands use of /υ/ in words such as but is slowly receding, for standard / / seems to have moved 25–50 miles north. Another recessive feature is perhaps the /ng/ in words such as finger, which occurs in the northwest midlands from Preston in the north to just south of Birmingham, but appears to be strong only in parts of Lancashire, Staffordshire and the west midlands.

In contrast to such recessive features, it is important to note that there are some innovative features which appear to have gained remarkable strength in a relatively short period of time. One such case involves the vocalisation of postvocalic /l/ in words such as milk. In standard English the pronunciation of this work is [m υ k] with a velarised [ ]. But in the southeastern corner of England, from Essex across to Hampshire, the l has been lost and we find [m υk]. The same area also shows the replacement of intervocalic /t/ with a glottal stop, as in /bʔə/ ‘butter’. This is often recognised as a stereotypical Cockney feature, but it is spreading, as is the process of glottalling, as in /ʔp/ ‘up’, although other dialects, such as in Scotland, appear to have independently innovated this change. The set of features we have just mentioned are commonly described as signs of ‘Estuary English’. From our point of view they demonstrate the large influence exercised on standard English by the dialects to the northeast of London. It is also important to distinguish this type of increasing use from merely stable or recessive dialect features. Thus the pronunciation of brother with a labiodental fricative, i.e. /br və/, remains a particularly Cockney feature (although Wright, 1892, found it near his native Windhill).

There is a widely held view that dialects are disappearing. This view is in many respects entirely correct. It does seem to be quite true that the variety of rural dialects with which we are presented in a work such as the SED is diminishing rapidly. This is due to obvious factors which we have already mentioned, such as the urbanisation of former countryside, the growth of mass media with its influence on the young, and the role of education and literacy in stigmatising local dialect. Yet this view does not reveal the full picture. Although rural dialects are indeed under threat, as they have been for a century or more, the history of urban dialects is rather different. To some extent, this is a historiographical issue. As we have seen, the rise of the study of dialects was essentially a nineteenthcentury phenomenon which was gradually refined until the time of the SED. Both for good reasons, such as the desire to record forms which were thought to be dying out, and for ideological reasons, connected with the desire to record ‘pure’ dialect, information about urban dialects was often ignored.

But there is also a methodological issue here, for the traditional approach was difficult to apply in urban areas, where the situation was very different. A solution to the difficulties only became possible with the emergence of what is

English in Britain |

379 |

now known as sociolinguistics. The first systematic sociolinguistic studies were undertaken by William Labov in New York in the mid-1960s; see Labov (1972) or, for a more detailed and extended account, Labov (1994). Britain had to wait for the studies of Norwich produced in the early 1970s by Peter Trudgill; see especially Trudgill (1974). Since then there have been an increasing number of important studies, several of which are mentioned in the Further Reading to this chapter.

It is important to recognise that sociolinguistics is not a rival to traditional dialectology. Yet it brought new methods of working and permitted an investigation of a much wider segment of the population, so that now younger, as well as older, informants could be sampled, and women, as well as men, were seen as proper subjects of study; also, in contrast to the SED, these sociolinguistic approaches were concerned with the interaction of different social classes. The consequences of such a revolution (that seems a more appropriate word than ‘evolution’) may not redraw the dialect geography of Britain, in the sense that the historical maps still hold. On the other hand, we now can draw new maps which can alter our perceptions of what is happening to dialects today.

This brings us back to the view that dialects are disappearing. Most of the sociolinguistic studies are based on precisely delimited areas: for example, Trudgill (1974) was a study of the sociolinguistics of Norwich; see also, for example, Milroy (1980), Cheshire (1982). This is inherent in the methodology. Nevertheless, there has been some geographically quite large-scale work done which is of the highest importance in assessing the state of present-day dialects. Perhaps the most interesting of these is Cheshire et al. (1993). This work was a first attempt to assess the language of schoolchildren throughout the British Isles. Although, for reasons outside the authors’ control, the study was not as fruitful as had been hoped, it still remains a foundation for further work in the area.

Perhaps the most important general result from this survey, and one which has been confirmed by more local studies, is that there has indeed been a process of dialect levelling, that is to say, there has been a decline in dialectal variety throughout Britain (although Scots and Ulster English tend to go their own way, presumably for reasons of national identity). But this decline in variety is not in the direction of standard English. Instead, what seems to be happening is that the different urban dialects are becoming more and more alike whilst remaining distinct from the standard.

In this survey the six most frequent usages (all with a percentage score of 85 per cent or higher) were:

them (Look at them big spiders)

should of (You should of left half an hour ago!)

‘no plural marking’ (. . . you need two pound of flour)

what as subject relative (The film what was on last night was good) never as past-tense negator (No, I never broke that)

there was with notional plural (There was some singers here a minute ago)

380 R I C H A R D H O G G

Even if there are some problems with this survey, the general outline is indisputable. Over a very wide range of urban dialects there has been a noticeable trend to level dialect forms so that it becomes sensible to consider the whole urban spread in England as tending to become a single unit. By and large these urban forms remain unacceptable in standard English, although there are signs that usages such as never and there was, as exemplified above, are acceptable in colloquial standard. Against this, the use of, for example, should of and relative what are both heavily stigmatised.

Perhaps an even more important aspect of this study is that the authors are able to demonstrate that in some features we can find evidence that there is a quite clearcut division between urban dialects and the dialects of surrounding regions. One interesting division occurs in a split between core Manchester dialects and other northwestern dialects. Core Manchester dialects use youse ‘you plural’, whilst the form is rare elsewhere; on the other hand, the same northwestern dialects regularly use demonstrative this here, that there, which is infrequent in Manchester, where them is preferred.

There is some temptation to assume that the phenomenon of dialect levelling will follow the pattern established in the standard language, where the predominant influence is from the southeastern part of the country. However, this seems to be less the case in the context of dialect levelling. One important example of levelling which seems to be spreading from other parts of the country is the replacement of present participle forms by past participle in the verbs sit and stand. Thus, where standard English has She was sitting there, He was standing there, in the urban dialects we are talking about, we find She was sat there, He was stood there. The latter forms are widely felt to be common only in the northwest of England, but in Cheshire et al. (1993) the evidence quite clearly shows the forms have become diffused over a large part of the country, including through much of the south.

A further result from this survey, which is of considerable interest, is that some usages in Scotland are quite divergent from those in England and Wales. For example, where the English schools reported demonstrative them (see above), the Scottish schools (all Glaswegian) reported thon, thae, yon. Similarly ain’t/in’t was absent from Scottish schools. Although this divergence could be trivial, it seems most likely that it is an indication of the continuing separation of Scots as a semi-autonomous variety of English.

There are, indeed, a great many dialect differences between Scots and any form of English. Not all these differences are merely the result of continuity from earlier periods, from the situation in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as we discussed in Section 7.4. This does not mean that there are no remnants of the earlier language, for there are: thus we can mention the mid-high front vowel /u/ in buik ‘book’ together with the merger of /u/ and /υ/ in that new phoneme, and the retention of postvocalic /r/; see the earlier discussion of loss of rhoticity in almost all English dialects. Remaining with phonology, the most obvious other aspect of Scots is the phenomenon known as Aitken’s Law; see Aitken (1981), Aitken & Macafee (2002), Lass (1974), Wells (1982), McClure

English in Britain |

381 |

(1994). Throughout Scots all vowels are short, except before a stem boundary, a voiced fricative or /r/. Typical examples, where English dialects have a long vowel, are Scots bead /bid/, lace /les/, cf. English /bi d/, /le s/. Perhaps the most obvious examples occur before inflectional forms so that there is a clear contrast between need /nid/ and knee+d /ni d/.

In syntax also, there are significant differences from English. Perhaps the best known of these concern modal verbs and negative marking. As in many other dialects, the variety of modal verbs is more restricted than in standard varieties, but Scots dialects have a distinctive usage not found elsewhere in Britain (except the contiguous area of Northumberland), although there are some parts of the US where the usage is found, notably in the Ohio–Pennsylvania area. The construction is called the Double Modal construction, and can be exemplified by sentences such as:

He might could do it if he tried (‘He would be able to do it . . .’)

She should can go tomorrow (‘She ought to be able to go tomorrow’)

The term Double Modal may not be fully accurate, since the following triple modal is equally possible:

He’ll might could do it for you (‘He might be able in the future to do it for you’)

Double modals are, of course, inherently interesting, since they break the usual assumption about English that there can only be one modal per verb phrase. But Scots also has a negation system which is different from that found in English dialects and which interacts with modals, so that we find sentences such as:

She couldnae hae telt him (‘It is not possible for her to have told him’)

She could no hae telt him (‘It was possible for her not to have told him’)

and even:

He couldnae hae no been no working (‘It is impossible that he has not been out of work’)

See further Brown (1991), Brown & Millar (1980). I have such forms in my own native dialect.

The evidence that we have just reviewed, from both English and Scottish dialects, supports quite strongly the belief that dialect levelling is taking place. This, however, should not lead us to assume that traditional rural dialects have completely disappeared, although they are undoubtedly on the decline, despite, I think, the comments of Trudgill (1999b: 108). But they are being replaced not so much by standard English as by a generalised non-standard variety. And this variety is different in the two countries, and could even be increasing because of external influences, such as the distinctive political atmosphere in Scotland.

The type of dialect levelling we have just discussed is sometimes reminiscent of the ‘colourless’ language which we noted in later Middle English. There are differences, to be sure, but there are also resemblances. However, there is another