aswath_damodaran-investment_philosophies_2012

.pdf

200 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

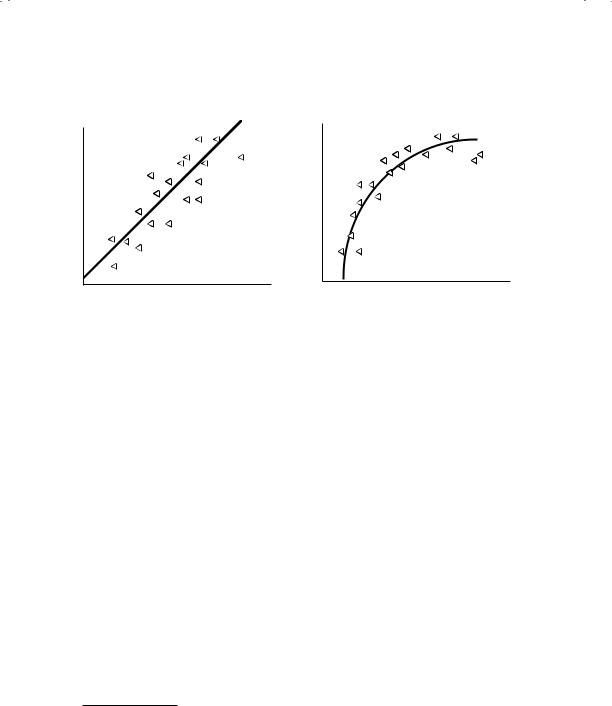

Panel A: Linear Relationship |

Panel B: Nonlinear Relationship |

F I G U R E 6 . 1 |

Scatter Plots—Linear and Nonlinear Relationships |

observe the latter, you may have to transform the variable to make the relationship more linear.36

Step 4: You can now run the regression of the dependent variable against the independent variables, with or without transformations.

In the example noted before, for instance, you would regress returns against P/E ratios, institutional holdings as a percentage of the stock outstanding, and the price change over the past six months:

Return on stock = a + b (P/E)

+c (Institutional holdings as % of stock)

+d (Stock price change over past six months)

If your hypothesis is right, you should expect to see the following:

b 0: Stocks with higher P/E ratios should have lower returns.

c 0: Stocks with higher institutional holdings should have lower returns.

d 0: Stocks that have done well over the past six months should have higher returns.

36Transformation requires you to convert a number by taking a mathematical function of it. Some commonly used transformations include the natural log, square root, and square. The natural log transformation is probably the most useful one in financial research.

Too Good to Be True? Testing Investment Strategies |

201 |

Once you run the regression, you have to pass it through the tests for statistical significance. In other words, even if all of the coefficients have the right signs, you have to check to ensure that they are significantly different from zero. In most regressions, statistical significance is estimated with a t-statistic for each coefficient. This t-statistic is computed by dividing the coefficient by the standard error of the coefficient. You can also compute an F statistic to measure whether the regression collectively yields statistically significant results.

The regression described here, where you look for differences across observations (firms, funds, or countries) at a point in time, is called a crosssectional regression. You can also use regressions to analyze how a variable changes over time as other variables change. For instance, it also long been posited that P/E ratios for all stocks go up as interest rates go down and economic growth increases. You could look at the P/E ratios for the entire market each year for the past 40 years, for instance, and examine whether P/E ratios have changed as interest rates and economic growth have changed. This regression is called a time series regression. Some inventive analysts even combine cross-sectional and time series data to create pooled regressions.

T H E L I M I T S O F R E G R E S S I O N S

Regressions are powerful tools to examine relationships, but they have their limits when it comes to testing market efficiency. The first problem that they share with all other tools is that they are only as good as the data that go into them. If your data are filled with errors, you should expect the regression output to reflect that. The second problem is that you make assumptions about the nature of the relationship between the dependent and independent variables that may not be

true. For instance, if you run a regression of returns against institutional holdings as a percentage of outstanding stock, you are assuming a linear relationship between the two—that is, that returns will change by the same magnitude if holdings go from 10 to 20 percent as they would if holdings went from 20 to 30 percent. The third problem arises when you run multiple regressions. For the regression coefficients to be unbiased, the independent variables should be uncorrelated with each other. In reality, it is difficult to find independent variables that have this characteristic.

202 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

T h e C a r d i n a l S i n s i n T e s t i n g M a r k e t E f f i c i e n c y

In the process of testing investment strategies, there are a number of pitfalls that have to be avoided. Some of them are:

Using anecdotal evidence to support or reject an investment strategy.

Anecdotal evidence is a double-edged sword. It can be used to support or reject the same hypothesis. Since stock prices are noisy and all investment schemes (no matter how absurd) will succeed sometimes and fail at other times, there will always be cases where the scheme works.

Testing an investment strategy on the same data and time period from which it was extracted. This is the tool of choice for the unscrupulous investment adviser. An investment scheme is extracted from hundreds through an examination of the data for a particular time period. This investment scheme is then tested on the same time period, with predictable results. (The scheme does miraculously well and makes immense returns.) An investment scheme should always be tested on a time period different from the one it is extracted from or on a universe different from the one used to derive the scheme.

Sampling biases. Since there are thousands of stocks that could be considered part of the testable universe of investments, researchers often choose to use a smaller sample. When this choice is random, this does limited damage to the results of the study. If the choice is biased, it can provide results that are not true in the larger universe. Biases can enter in subtle ways. For instance, assume that you decide to examine whether stocks with low prices are good investments, and you test this by estimating the returns over the past year for stocks that have low prices today. You will almost certainly find that this portfolio does badly, but not because your underlying hypothesis is false. Stocks that have gone down over the past year are more likely to have low stock prices today than stocks that have gone up. By looking at low stock prices today, you created a sample that is biased toward poorly performing stocks. You could very easily have avoided this bias by looking at stock prices at the start of your return period (rather than the end of the period).

Failure to control for market performance. A failure to control for overall market performance can lead you to conclude that your investment scheme works just because it makes good returns or does not work just because it makes poor returns. Most investment strategies will generate good returns in a period in which the market does well and few will do so when the market does badly. It is crucial, therefore, that investment schemes control for market performance during the period of the test.

Too Good to Be True? Testing Investment Strategies |

203 |

Failure to control for risk. A failure to control for risk leads to a bias toward accepting high-risk investment schemes and rejecting low-risk investment schemes, since the former should make higher returns than the market and the latter should make lower returns, without implying any excess returns. For instance, a strategy of investing in the stock of bankrupt companies may generate annual returns that are much higher than returns on the S&P 500, but it is also a much riskier strategy and has to be held to a higher standard.

Mistaking correlation for causation. Statistical tests often present evidence of correlation, rather than causation. Consider the study on P/E stocks cited in the earlier section. We concluded that low-P/E stocks tend to have higher excess returns than high-P/E stocks. It would be a mistake to conclude that a low price-earnings ratio, by itself, causes excess returns, since the high returns and the low P/E ratio themselves might have been caused by the high risk associated with investing in the stocks. In other words, high risk might be the causative factor that leads to both of the observed phenomena—low P/E ratios on the one hand and high returns on the other. This insight would make us more cautious about adopting a strategy of buying low-P/E stocks in the first place.

S o m e L e s s e r S i n s T h a t C a n B e a P r o b l e m

While the errors in the last section can be fatal, there are lesser errors that researchers make that can color their conclusions. Here is a partial list.

Data mining. The easy access that we have to huge amounts of data on stocks today can be a double-edged sword. While it makes it far easier to test investment strategies, it also exposes us to the risk of what is called data mining. When you relate stock returns to hundreds of variables, you are bound to find some that seem to predict returns, simply by chance. This will occur even if you are careful to sample without bias and test outside your sample period.

Survivor or survival bias. Most researchers start with an existing universe of publicly traded companies and work back through time to test investment strategies. This can create a subtle bias since it automatically eliminates firms that failed during the period, with obvious negative consequences for returns. If the investment scheme is particularly susceptible to picking firms that have high bankruptcy risk, this may lead to an overstatement of returns on the scheme. For example, assume that the investment scheme recommends investing in stocks that have very negative earnings, using the argument that these stocks are most likely

204 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

to benefit from a turnaround. Some of the firms in this portfolio will go bankrupt, and a failure to consider these firms will overstate the returns from this strategy.

Not allowing for transaction costs. Some investment schemes are more expensive than others because of transaction costs—execution fees, bid-ask spreads, and price impact. A complete test will take these into account before it passes judgment on the strategy. This is easier said than done, because different investors have different transaction costs, and it is unclear which investor’s trading cost schedule should be used in the test. Most researchers who ignore transaction costs argue that individual investors can decide for themselves, given their transaction costs, whether the excess returns justify the investment strategy.

Not allowing for difficulties in execution. Some strategies look good on paper but are difficult to execute in practice, either because of impediments to trading or because trading creates a price impact. Thus a strategy of investing in very small companies may seem to create excess returns on paper, but these excess returns may not exist in practice because the price impact is significant.

A S K E P T I C ’ S G U I D E T O I N V E S T M E N T S T R A T E G I E S

At the start of this chapter, we noted that investors are bombarded with sales pitches for “can’t miss” investment strategies. Increasingly, these strategy sales pitches come with what look like impressive back-tests that show that the strategy in question handily beats the market. If the proof is in the actual performance, it is also clear that most of these strategies really do not work and that we as investors need to develop ways of separating the wheat from the chaff. Here is a checklist that may help the next time you review a strategy.

Can the investment strategy be tested and implemented?

There are some investment strategies that sound good but are difficult to test and even more difficult to implement. There are two reasons for this. The first is that the strategy is based on qualitative factors that are nebulous and subject to interpretation. For instance, a strategy that requires you to invest in well-managed companies but does not specify what qualifies as good management is essentially useless. The second is that the strategy requires you to have access to information that you could not possess unless you were a time traveler. Thus, a market timing strategy that requires you to invest in stocks at the start of each year if the real economic growth in

Too Good to Be True? Testing Investment Strategies |

205 |

the last quarter of the prior year exceeds 4 percent has a fatal flaw, since the government does not report on the last quarter until February or March of the next year.

If the strategy can be tested, is the test that has been devised a fair one of the strategy?

When testing a strategy, you have to make judgment calls on a number of dimensions. You have to decide first on the time period over which you will assess the strategy, and that choice should reflect the selling point of the strategy. Thus, if an investment strategy is presented as one that protects you during market downturns, it has to be tested over a period in which there was enough market turbulence to test that claim. In general, testing an investment strategy over a period in which the market has generally moved in one direction (bullish or bearish) is dangerous, since the future will almost certainly deliver a mix of both good and bad times. You also have to make measurement choices on the variables you will use to capture the essence of the strategy. Those choices will be easy for those strategies that are built around clearly defined variables (price-to-book value ratio, for instance) but is more complicated for those strategies built around variables that can be captured with different measures (high growth, for example, can be defined as growth in revenues or earnings, and can be computed from the past or be an estimate for the future).

Does it pass the statistical tests?

In the preceding sections, we laid out the cardinal and lesser sins that bedevil the statistical tests of investment strategies. When looking at any back-test of a strategy, you should start by looking at the size of the sample (larger samples are better than smaller samples) and sampling bias (checking in particular for whether the way in which the sample was created is likely to skew the final conclusions). You should follow up by looking at how statistical significance is being established and whether there are features to the data that may contaminate the statistical tests being used to make the case.

Does it pass the economic significance tests?

As we noted earlier, what passes for statistical significance, especially with large samples, may not pass the economic significance test. In particular, there are three checks that should be performed. The first is on the magnitude of the additional returns; thus a strategy may claim to beat the market, but does it beat it by 0.2 percent, 2 percent, or 20 percent a year? The second is in the risk adjustments. We listed a number of different riskadjustment measures that can be used; in addition, there is a commonsense test that should always be applied. Take a look at the stocks (or other assets) that come through as the ones to buy based on the strategy, and see

206 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

if they reflect the study’s claims on the risk exposure. Thus, a strategy that claims to have average or low risk will be undermined if most of the stocks that show up on the list are young, high-growth companies. Finally, you should consider the potential trading costs that you will be exposed to on the strategy, given the types of stocks or assets it requires you to invest in and how often and when you have to trade.

Has it been tried before?

There is truth to the saying that almost everything that is marketed as new and different in investing has been tried before, sometimes successfully and sometimes not. While investors often view market history as obscure and irrelevant, especially given how much markets have changed over time, you can learn by looking at how investors in the past fared with strategies similar to the one that is being tested. If it worked, how long and how well did it work? If it did not work, why did it fail? If there is a new twist or variant that is being incorporated into the strategy, will it help to avoid repeating that failure? If you do have an investment strategy that has never been tried before, it is worth asking why. It is possible that the new assets or markets have made it feasible for the first time, but it is also possible that there is a fatal flaw to the strategy that you don’t see yet.

C O N C L U S I O N

The question of whether markets are efficient will always be a provocative one, given the implications that efficient markets have for investment management and research. If an efficient market is defined as one where the market price is an unbiased estimate of the true value, it is quite clear that some markets will always be more efficient than others and that markets will always be more efficient to some investors than to other investors. The capacity of a market to correct inefficiencies quickly will depend, in part, on the ease of trading, the transaction costs, and the vigilance of profit-seeking investors in that market.

Market efficiency can be tested in a number of different ways. The three most widely used tests to test efficiency are event studies, which examine market reactions to information events; portfolio studies, which evaluate the returns of portfolios created on the basis of observable characteristics; and regressions that relate returns to firm characteristics either at a point in time or across time. It does make sense to be vigilant, because bias can enter these studies, intentionally or otherwise, in a number of different ways and can lead to unwarranted conclusions and, worse still, to wasteful investment strategies.

Too Good to Be True? Testing Investment Strategies |

207 |

E X E R C I S E S

Pick an investment strategy that intrigues you. It can be a strategy that you have used before or that you have read about.

1.Is the strategy testable? If it is not, would you still use it? Why or why not?

2.Assuming that it is testable, what type of test you would need to run to evaluate the strategy—an event study, a portfolio study, or something else?

3.Once you have decided on the type of test, consider the details of how you would go about running the test. (You may not actually have the resources to run the test, but you can still think about how you would do it if you did have the resources.)

a.Over what time period would you test the strategy?

b.How big does your sample have to be for you to feel comfortable with the results?

c.Once you have chosen a time period and sample size, what are the steps involved in running the test?

d.How do you plan to incorporate risk and transaction costs into your analysis?

e.Assuming that the strategy generates excess returns, what residual concerns would you still have in implementing the strategy?

Lessons for Investors

An efficient market makes mistakes, but the mistakes tend to be random. In other words, you know that some stocks are undervalued and some are overvalued, but you have no way of identifying which group each stock falls into.

You are more likely to find inefficiencies in markets that are less liquid and where information is less easily available or accessible.

In an inefficient market, you can use publicly available information to find undervalued and overvalued stocks and trade on them to earn returns that are consistently greater than what you would have earned on a randomly selected portfolio of equivalent risk.

To create portfolios of equivalent risk, you have to use models for risk and return. To the extent that your model for risk is misspecified, you may uncover what look like inefficiencies but really represent the failures of your model.

CHAPTER 7

Smoke and Mirrors?

Price Patterns, Volume Charts,

and Technical Analysis

Some investors believed that price charts provide signals of the future, and pore over them looking for patterns that will predict future price movements. Notwithstanding the disdain with which they are viewed by other investors and many academics, easy access to data combined with an increase in computing capabilities—charting and graphing programs abound—has meant that more investors look at charts now than ever before. In addition, data on trading volume and from derivatives markets have provided

chartists with new indicators to pore over.

In this chapter, we look at the basis of charting by examining the underlying premise in charting and technical analysis, which is a belief that there are systematic and often irrational patterns in investor behavior and that technical indicators and charts provide advance warning of shifts in investor behavior. While we will not attempt to describe every charting pattern and technical indicator (there are hundreds), we will categorize them based on the view of human behavior that underlies them. In the process, we will see if there are lessons in charts that even nonbelievers can take away and cautionary notes for true believers about potential inconsistencies.

R A N D O M W A L K S A N D P R I C E P A T T E R N S

In many ways, the antithesis of charting is the notion that prices follow a random walk. In a random walk, the stock price reflects the information in past prices, and knowing what happened yesterday is of no consequence to what will happen today. Since the random walk comes in for a fair degree

209