340 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

Pradhuman, in his book on small cap investing, contrasts a strategy of buying small-cap value stocks with small-cap growth stocks and presents several results. First, the excess return on a small-cap value strategy is less than the sum of the excess return on a value strategy and the excess return on a small-cap strategy. In other words, there is some leakage in returns from both strategies when you combine them. Second, the difference in returns between value and growth small-cap stocks mirrors the difference in returns between value and growth large-cap stocks, but the cycles are exaggerated. In other words, when value stocks outperform (or underperform) growth stocks across the market, small-cap value stocks outperform (or underperform) smallcap growth stocks by an even larger magnitude. Third, the excess returns in the past two decades on a small-cap value strategy seem to be more driven by the value component than by the small cap component.9

I n i t i a l P u b l i c O f f e r i n g s

In initial public offerings (IPOs), private firms make the transition to being publicly traded firms by offering their shares to the public. In contrast with equity issues by companies that are already publicly traded, where there is already a market price for the stock that acts as an anchor, an initial public offering has to be priced by an investment banker based on perceptions of demand and supply. There are some investors who believe that they can exploit both the uncertainty in the process and the biases brought to the pricing by investment bankers to make excess returns.

T h e P r o c e s s o f a n I n i t i a l P u b l i c O f f e r i n g When a private firm becomes publicly traded, the primary benefit it gains is increased access to financial markets and to capital for projects. This access to new capital is a significant gain for high-growth businesses with large and lucrative investment opportunities. A secondary benefit is that the owners of the private firm are able to cash in on their success by attaching a market value to their holdings. These benefits have to be weighed against the potential costs of being publicly

9He came to this conclusion by regressing excess returns on stocks against market capitalization and price-to-book ratio. The latter explained far more of the differences in excess returns than the former.

The Allure of Growth: Small Cap and Growth Investing |

341 |

traded. The most significant of these costs is the loss of control that may ensue from being a publicly traded firm. Other costs associated with being a publicly traded firm are the information disclosure requirements and the legal requirements.10 Assuming that the benefits outweigh the costs, there are several steps involved in an initial public offering.

Once the decision to go public has been made, a firm generally cannot approach financial markets on its own. This is so because it may be largely unknown to investors and does not have the expertise to go public without help. Therefore, a firm has to pick intermediaries to facilitate the transaction. These intermediaries are usually investment banks which provide several services.

First, they help the firm meet the information disclosure and filing requirements of the public markets. In order to make a public offering the United States, a firm has to file a registration statement and prospectus with the SEC, providing information about the firm’s financial history, its forecasts for the future, and how it plans to use the funds it raises from the initial public offering. The prospectus provides information about the riskiness and prospects of the firm for prospective investors in its stock. Second, they provide the credibility a small and unknown private firm may need to induce investors to buy its stock. Third, they provide their advice on the valuation of the company and the pricing of the new issue. Fourth, they absorb some of the risk in the issue by guaranteeing an offer price on the issue; this guarantee is called an underwriting guarantee. Finally, they help sell the issue by assembling an underwriting syndicate, who try to place the stock with their clients. The underwriting syndicate is organized by one investment bank, called the lead investment bank, and private firms tend to pick investment bankers based on reputation and expertise, rather than price. A good reputation provides the credibility and the comfort level needed for investors to buy the stock of the firm; expertise applies not only to the pricing of the issue and the process of going public but also to other financing decisions that might be made in the aftermath of a public issue. The investment banking agreement is then negotiated, rather than opened up for competition.

Once the firm chooses an investment banker to take it public, the next step is to estimate a value for the firm. This valuation is generally done by the lead investment bank, with substantial information provided by the issuing firm. The value is sometimes estimated using discounted cash flow

10The costs are twofold. One is the cost of producing and publicizing the information itself. The other is the loss of control over how much and when to reveal information about the firm to others.

342 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

models, similar to those described in Chapter 5. More often, though, the value is estimated by using a pricing multiple, estimated by looking at comparable firms that are already publicly traded. Whichever approach is used, the absence of substantial historical information, in conjunction with the fact that these are small companies with high growth prospects, makes the estimation of value an uncertain one at best. The other decision the firm has to make relates to the size of the initial issue and the use of the proceeds. In most cases, only a portion of the firm’s stock is offered at the initial public offering; this reduces the risk on the underpricing and enables the owners to test the market before they try to sell more stock. In most cases, the firm uses the proceeds from the initial stock issue to finance new investments.

The next step in this process is to set the value per share for the issuer. To do so, the equity in the firm is divided by the number of shares, which is determined by the price range the issuer would like to have on the issue. If the equity in the firm is valued at $50 million, for example, the number of shares would be set at 5 million to get a target price range of $10 per share, or at 1 million shares to get a target price range of $50 per share. The final step in this process is to set the offering price per share. Most investment banks set the offering price below the estimated value per share for two reasons. First, it reduces the bank’s risk exposure, since it ensures that the shares will be bought by investors at the offering price. (If the offering price is set too high and the investment bank is unable to sell all of the shares being offered, it has to use its own funds to buy the shares at the offering price.) Second, investors and investment banks view it as a good sign if the stock increases in price in the immediate aftermath of the initial issue. For the clients of the investment banker who get the shares at the offering price, there is an immediate payoff; for the issuing company, the ground has been prepared for future issues. In setting the offering price, investment bankers have the advantage of first checking investor demand. This process, which is called building the book, involves polling institutional investors prior to pricing an offering to gauge the extent of the demand for an issue. It is also at this stage in the process that the investment banker and issuing firm will present information to prospective investors in a series of presentations called road shows. In this process, if the demand seems very strong, the offering price will be increased; in contrast, if the demand seems weak, the offering price will be lowered. In some cases, a firm will withdraw an initial public offering at this stage11 if investors are not enthusiastic about it.

11One study of initial public offerings between 1979 and 1982 found that 29 percent of firms terminated their initial public offerings at this stage in the process.

The Allure of Growth: Small Cap and Growth Investing |

343 |

Once the offering price has been set, the die is cast. If the offering price has indeed been set below the true value, the demand will exceed the offering, and the investment banker will have to choose a rationing mechanism to allocate the shares. On the offering date—the first date the shares can be traded—there will generally be a spurt in the market price. However, if the offering price has been set too high, as is sometimes the case, the investment bankers will have to discount the offering to sell it and make up the difference to the issuer because of the underwriting agreement.

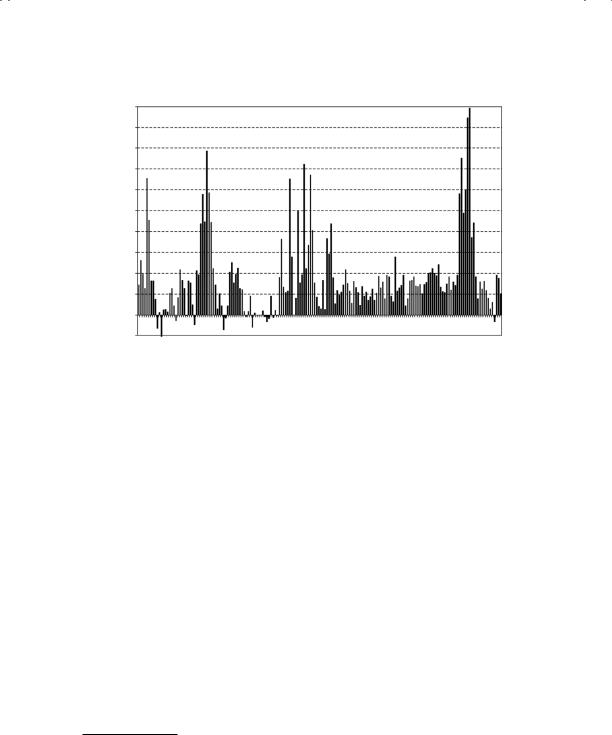

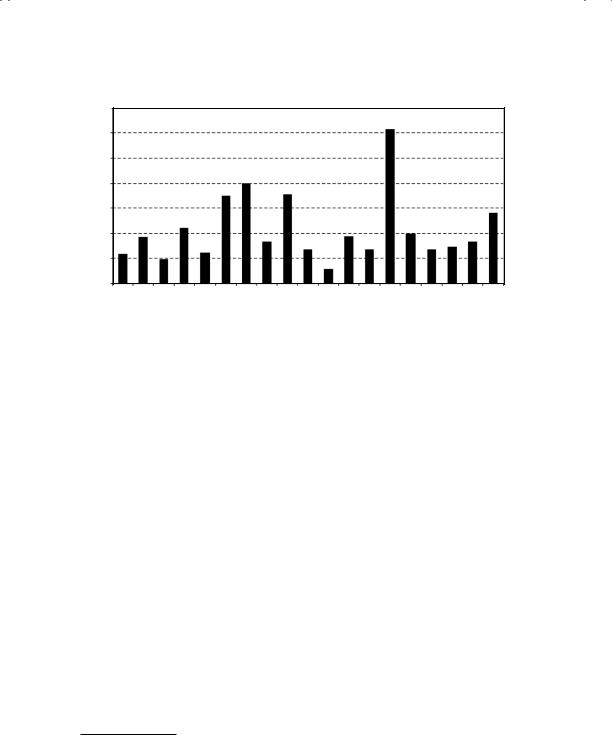

I P O P r i c i n g : T h e E v i d e n c e How well do investment bankers price initial public offerings? One way to measure this is to compare the price when the stock first starts trading to the offering price. Precise estimates vary from year to year, but the average initial public offering seems to be underpriced by about 10 percent to 15 percent. The underpricing also seems to be greater for smaller public offerings. One study estimates the underpricing as a function of the issue proceeds for 1,767 IPOs between 1990 and 1994, and the results are presented in Figure 9.8.12

|

18.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

date |

14.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

on offering |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2–10 |

10–20 |

20–40 |

40–60 |

60–80 |

80–100 |

100–200 |

200–500 |

>500 |

Proceeds of IPO (in $millions)

F I G U R E 9 . 8 Average Initial Return and Issue Size

Source: I. Lee, S. Lockhead, J. R. Ritter, and Q. Zhao, “The Costs of Raising Capital,” Journal of Financial Research 19 (1996): 59–74.

12I. Lee, S. Lockhead, J. R. Ritter, and Q. Zhao, “The Costs of Raising Capital,”

Journal of Financial Research 19 (1996): 59–74.

344 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

100.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

90.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

80.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

70.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–10.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1960 |

1963 |

1965 |

1968 |

1970 |

1973 |

1975 |

1978 |

1980 |

1983 |

1985 |

1988 |

1990 |

1993 |

1995 |

1998 |

2000 |

2003 |

Year

F I G U R E 9 . 9 IPO Underpricing over Time

Source: A. Ljundquist, IPO Underpricing, Handbooks in Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance, edited by Espen Eckbo (Elsevier/North Holland Press (2004)).

The smaller the issue, the greater the underpricing; the smallest offerings often are underpriced by more than 17 percent, but the underpricing is much less for the larger issues.

In a comprehensive survey article on IPO underpricing in 2004, Ljundquist presents two additional findings about the phenomenon.13 First, he notes that the degree of underpricing has varied widely over time in the United States and presents the average offering date returns (a rough measure of underpricing) across time in Figure 9.9.

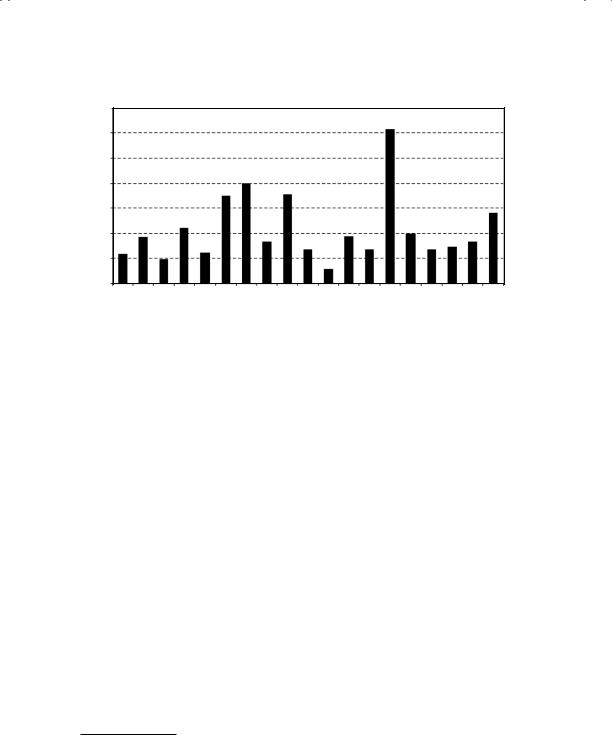

Note the dramatic underpricing in 1999 and 2000, when the average IPO jumped by 71 percent and 57 percent on the opening date respectively, and that IPO markets move in cycles, with underpricing increasing in the hot periods and shrinking during other periods. Second, Ljundquist expands the analysis to look at public offerings in 19 European markets in Figure 9.10, and notes that IPOs are underpriced, on average, in every single one. As attention shifts toward emerging markets, initial public offerings have boomed in Asia and Latin America in the past few years. Boulton, Smart, and

13A. Ljundquist, IPO Underpricing, Handbooks in Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance, edited by Espen Eckbo (2004).

The Allure of Growth: Small Cap and Growth Investing |

345 |

70.0

60.0

50.0

40.0

30.0

20.0

10.0

0.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hung |

|

|

|

|

|

Portugal |

Spain |

|

|

Kingdom |

Austria |

Denmark |

France |

Greece |

Irelan |

LuxembourgNetherlan |

ds |

|

Switzerland |

|

|

Germany |

|

|

|

|

|

Belgium |

Finland |

|

|

|

|

d |

|

|

Swe |

den |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ary |

|

|

Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United |

|

F I G U R E 9 . 1 0 |

IPO Underpricing in European Markets |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: A. Ljundquist, IPO Underpricing, Handbooks in Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance, edited by Espen Eckbo (Elsevier/North Holland Press (2004)).

Zutter estimate the degree of underpricing across 37 countries, including many emerging markets, and evaluate reasons for differences.14 In particular, they find that IPO underpricing decreases with earnings quality; the underpricing is greatest in countries with poor information disclosure standards and opaque financial statements. The price jumps about 121 percent on the offering date for a typical Chinese IPO but only about 7 percent for the average Brazilian IPO.

While the evidence that initial public offerings go up in price on the offering date is strong, it is not clear that these stocks are good investments in the years after. Loughran and Ritter tracked returns on 5,821 IPOs in the five years after the offerings and contrasted them with returns on nonissuers in Figure 9.11. Note that the IPO firms consistently underperform the nonissuing firms and that the underperformance is greatest in the first few years after the offering. This phenomenon is less pronounced for larger initial public offerings, but it still persists. Put succinctly, the primary payoff to investing in IPOs comes from getting the shares at the offering price and not from buying the shares in the after market.

14T. J. Boulton, S. B. Smart, and C. J. Zutter, “Earnings Quality and International IPO Underpricing,” Accounting Review 86 (2010): 483–505.

346 |

|

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

16% |

|

|

14% |

|

|

12% |

|

|

Return |

|

|

|

10% |

|

|

Annual |

8% |

|

|

6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4% |

|

|

|

2% |

|

|

|

0% |

|

Nonissuers |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

IPO’s |

|

3 |

4 |

|

Year after Offering |

5 |

|

|

F I G U R E 9 . 1 1 Postissue Returns—IPOs versus Non-IPOs

Source: T. Loughran and J. R. Ritter, “The New Issues Puzzle,” Journal of Finance 50, 23–51.

I n v e s t m e n t S t r a t e g i e s Given the evidence on underpricing of IPOs and the substandard returns in the years after, are there investment strategies that can be constructed to make money on IPOs? In this section, we consider two. In the first, we adopt the bludgeon approach, trying to partake in every initial public offering and hoping to benefit from the offering day jump (chronicled in the preceding studies). In the second, we adopt a variant of momentum investing, riding IPOs in hot markets and avoiding them in cold markets. In the last, we look at refinements that allow us to invest selectively in those IPOs where the odds best favor investors.

The Bludgeon Strategy: Invest in Every IPO If initial public offerings, on average, are underpriced, an obvious investment strategy is to subscribe to a large number of initial public offerings and to construct a portfolio based on allotments of these offerings. There is, however, a catch in the allotment process that may prevent this portfolio from earning excess returns from the average underpricing. When investors subscribe to initial public offerings, the number of shares that they are allotted will depend on whether and by how much the offering is underpriced. If it is significantly underpriced, you will get only a fraction of the shares that you requested. However, if the offering is correctly priced or overpriced, you will get all of the shares that you requested. Thus, your portfolio will be underweighted

The Allure of Growth: Small Cap and Growth Investing |

347 |

in underpriced initial public offerings and overweighted in overpriced offerings.

Is there a way in which you can win this allotment game or in the postoffering market? There are two strategies that you can adopt, though neither guarantees success. The first is to be the beneficiary of a biased allotment system, where the investment bank gives you more than your share of your requested shares in underpriced offerings. The second is to bet against the herd and sell short on IPOs just after they go public, hoping to make money from the price decline in the following months. The peril with this strategy is that the newly listed stocks are not always liquid, and selling short can be both difficult and dangerous.

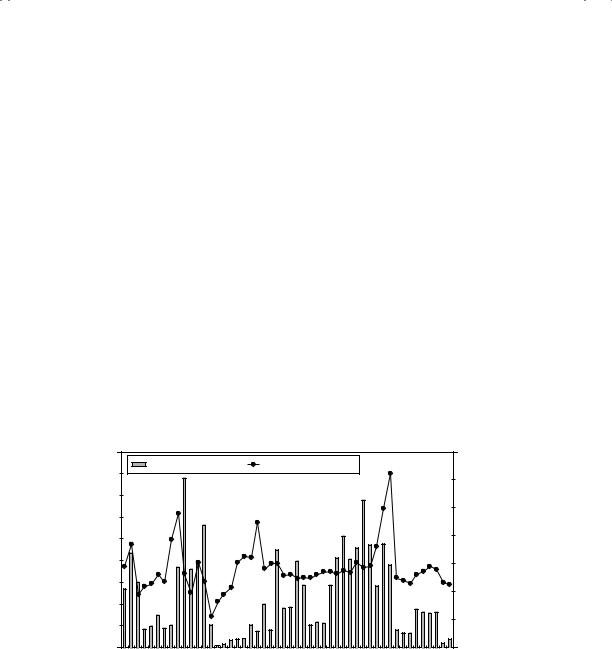

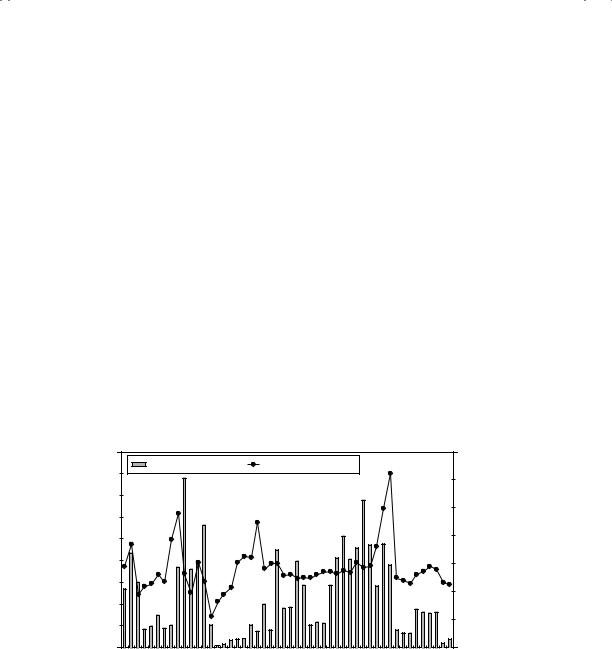

Ride the Wave: Invest Only in Hot Markets Initial public offerings ebb and flow with the overall market, with both the number of offerings and the degree of underpricing moving in waves. There are periods when the market is flooded with initial public offerings, with significant underpricing, and periods when there are very few offerings, with a concurrent drop-off in underpricing as well. Contrast, for instance, the salad days of the late 1990s, when firms went public at an extraordinary pace, and 2001, when the number slowed to a trickle. Figure 9.12 provides a summary of the

900 |

100.00% |

Number of Offerings |

Average Initial Return |

800 |

80.00% |

|

700 |

|

600 |

60.00% |

|

500 |

40.00% |

|

400 |

20.00% |

300 |

0.00% |

|

200 |

|

100 |

–20.00% |

|

0 |

–40.00% |

1960196219641966196819701972197419761978198019821984198619881990199219941996199820002002200420062008 |

|

Year |

|

F I G U R E 9 . 1 2 Number of IPOs and Average Initial Return

Source: A. Ljundquist, IPO Underpricing, Handbooks in Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance, edited by Espen Eckbo (Elsevier/North Holland Press, 2004)). For the most recent years, we used data from IPOcentral.com, a website that tracks IPOs.

348 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

number of offerings made each year from 1960 to 2010 and the average initial returns on those offerings.

Note that the number of offerings drops to almost zero in the early 1970s and the returns to IPOs drop as well. The same phenomenon occurs after the dot-com crash of 2001–2002 and the banking crisis of 2008–2010. A strategy of riding the IPO wave would therefore imply investing when the IPO market is hot, with lots of offerings and significant underpricing, and steering away from IPOs in the lean years.

This strategy is effectively a momentum strategy, and the risks are similar. First, while it is true that the strategy generates returns, on average, across the entire hot period, whether you make money or not depends largely upon how quickly you recognize the beginning of a hot IPO market (with delayed entry translating into lower returns) and its end (since the IPO listings toward the very end of the hot market are the ones most likely to fail). Second, the initial public offerings during any period tend to share a common sector focus. For instance, the bulk of the initial public offerings during 1999 were of young technology and telecom firms. Investing only in these public offerings will result in a portfolio that is not diversified in periods of plenty, with an overweighting in whichever sector is in favor at that point in time.

The Discriminating IPO Investor If the biggest danger of an IPO investment strategy is that you may be saddled with overpriced stocks (either because you received your entire allotment of an overpriced IPO or because you are approaching the end of a hot IPO cycle), incorporating a value focus may allow you to avoid some of the risk. Thus, rather than invest in every IPO listing across time or in hot markets, you will invest only in those IPOs where the odds of underpricing are greatest. This will require an investment of time and resources prior to the offering, where you use the information in the prospectus and other public filings to value the company, employing either intrinsic or relative valuation models. You will then use the value estimates from your analysis to decide on which IPOs to invest in and which ones to avoid.

There are two potential pitfalls with this strategy. The first is that your valuation skills have to be well honed, because valuing a company going public is generally much more difficult than valuing one that is already listed. While companies going public have to provide information on their financial standing and what they plan to use the offering proceeds for, they also tend to be younger, high-growth firms. As a consequence, not only is there less of a financial history for the firm, but that history is not as useful in forecasting the future. The second is that, as we noted in the earlier

The Allure of Growth: Small Cap and Growth Investing |

349 |

section, IPO markets go through cycles, with the number of underpriced offerings dropping to a handful in cold markets. Thus, your task may end up being finding the least overpriced IPOs rather than underpriced ones, and then working out an exit strategy for selling these stocks before the correction hits.

D e t e r m i n a n t s o f S u c c e s s A strategy of investing in initial public offerings makes more sense as an ancillary strategy rather than a primary strategy, partly because of the sector concentration of initial public offerings during hot periods and partly because of the absence of offerings during cold periods. Assuming that it is used as an ancillary strategy, you would need to do the following to succeed:

Have the valuation skills to value companies with limited information and considerable uncertainty about the future, so as to be able to identify public offerings that are underpriced or overpriced.

Since this is a short-term strategy, often involving getting the shares at the offering price and flipping the shares shortly after the offering date, you will have to gauge the market mood and demand for each offering, in addition to assessing its value. In other words, a shift in market mood can leave you with a large allotment of overpriced shares in an initial public offering.

Play the allotment game well, asking for more shares than you want in companies that you view as severely underpriced and fewer or no shares in firms that are overpriced or that are priced closer to fair value.

Be ready to be a global investor, as initial public offerings increasingly shift to emerging markets in Asia and Latin America.

In recent years, investment banks have used the allotment process to reward selected clients. In periods when demand for initial public offerings is high, they have also been able to punish favored investors who flip shares for a quick profit by withholding or rationing future allotments. If you are required to hold these stocks for the long term to qualify for the initial offering, you may very well find that the superior performance of these stocks in the initial offering period can very quickly be decimated by poor returns in subsequent periods.

G r o w t h S c r e e n s

If you are a portfolio manager whose choices come from a very large universe of stocks, your most effective way of building a portfolio may be to screen