aswath_damodaran-investment_philosophies_2012

.pdf

Information Pays: Trading on News |

381 |

the excess returns earned are not very large. Lakonishok and Lee took a closer look at the price movements around insider trading. They found that firms with substantial insider selling had stock returns of 14.4 percent over the subsequent 12 months, which was significantly lower than the 22.2 percent earned by firms with insider buying. However, they found that the link between insider trading and subsequent returns was greatest for small companies and that there was almost no relationship at larger firms. They also noted that it was far weaker for long-term returns than for short-term returns.

Over the past two decades, there have been two developments that have affected the profitability of insider trading in the United States. The first is that the SEC has become more expansive in its definition of what constitutes insider information (to include any material nonpublic information, rather than just information releases from the firm) and more aggressive in its enforcement of insider trading laws. The second is that companies, perhaps in response to the SEC’s hard line on insider trading, have adopted more stringent policies restricting insiders from trading on information. Perhaps as a consequence, the price effect of insider trading has decreased over time, and one study finds that the price effect of (legal) insider trading has almost disappeared since 2002, with the adoption of Regulation Fair Disclosure (Regulation FD), which restricts selective information disclosure by companies to a few investors or analysts, and Sarbanes-Oxley, which increased scrutiny of insider trading.4

Is insider trading more informative (and profitable) in some firms than in others? A study that looked at differences across firms finds that insider trading is more profitable in less transparent firms and where analyst disagreement about future earnings growth is greatest.5 In a related finding, Aboody and Lev note that insider trades are more profitable at firms with significant research and development (R&D) expenditures than at firms without these expenditures; arguably, the payoff and likely success of R&D investments are more difficult for outsiders to assess.6

In the past few years, there have been attempts to examine the returns earned by insiders in other markets, and the results are consistent with findings in the United States over time. In markets like the United

4I. Lee, M. Lemmon, Y. Li, and J. M. Sequeira, “The Effects of Regulation on the Volume, Timing, and Profitability of Insider Trading” (SSRN Working Paper 1824185, 2011).

5Y. Wu and Q. Zhu, “When Is Insider Trading Informative?” (SSRN Working Paper 1917132, 2011).

6D. Aboody and B. Lev, “Information Asymmetry, R&D, and Insider Gains,” Journal of Finance 56 (2000): 2747–2766.

382 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

Kingdom, where insider trading is expansively defined and strongly enforced, the profits to insider trading are minimal.7 In many emerging markets, where insider trading is defined narrowly and/or it is not prosecuted with vigor, insider buying is associated with subsequent price increases, and selling with price decreases.

C a n Y o u F o l l o w I n s i d e r s ? If insider trading offers advance warning, albeit a noisy one, of future price movements, can we as outside investors use this information to make better investment decisions? In other words, when looking for stocks to buy, should we consider the magnitude of insider buying and selling on the stock? To answer this question, we first have to recognize that since the SEC does not require an immediate filing of insider trades, investors will find out about insider trading on a stock with a lag of a few weeks or even a few months. In fact, until recently, it was difficult for an investor to access the public filings on insider trading. As these filings have been put online in recent years, this information on insider trading has become available to more and more investors.

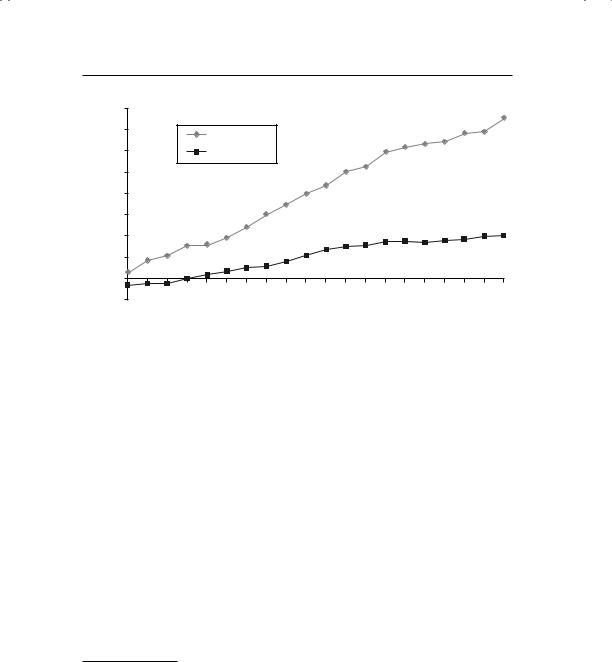

A study of insider trading examined excess returns around both the date the insiders report to the SEC and the date that information becomes available to investors in the official summary.8 Figure 10.5 presents the contrast between the two event studies.

Given the opportunity to buy on the date the insider reports to the SEC, investors could have marginal excess returns (of about 1 percent), but these returns diminish and become statistically insignificant if investors are forced to wait until the official summary date. If you control for transaction costs, there are no excess returns associated with the use of insider trading information. Does this mean that insider trading information is useless? It may be so if we focus on total insider buying and selling, but there may be value added if we can break down insider trading into more detail. Consider the following propositions:

Not all insiders have equal access to information. Top managers and members of the board should be privy to much more important information, and thus their trades should be more revealing. A study by Bettis, Vickrey, and Vickrey finds that investors who focus only on large

7D. Andriosopoulos and H. Hoque, “Information Content of Aggregate and Individual Insider Trading” (SSRN Working Paper 1959549, 2010).

8H. N. Seyhun, “Insiders’ Profts, Costs of Trading and Market Efficiency,” Journal of Financial Economics 16 (1986): 189–212.

Information Pays: Trading on News |

383 |

4%

3%

2%

1%

0%

–1%

–2%

–200 |

Insider |

Official |

+300 |

|

Reporting |

Summary |

|

|

Date |

Date |

|

Days around event date

F I G U R E 1 0 . 5 Abnormal Returns around Reporting Day: Official Summary Availability Day

Source: H. N. Seyhun, “Insiders’ Profts, Costs of Trading and Market Efficiency,”

Journal of Financial Economics 16 (1986): 189–212.

trades made by top executives rather than total insider trading may, in fact, be able to earn excess returns.9

As investment alternatives to trading on common stock have multiplied, insiders have also become more sophisticated about using these alternatives. As an outside investor, you may be able to add more value by tracking these alternative investments. For instance, Bettis, Bizjak, and Lemmon find that insider trading in derivative securities (options specifically) to hedge their common stock positions increases immediately following price run-ups and prior to poor earnings announcements. In addition, they find that stock prices tend to go down after insiders take these hedging positions.10

9J. Bettis, D. Vickrey, and Donn Vickrey, “Mimickers of Corporate Insiders Who Make Large Volume Trades,” Financial Analysts Journal 53 (1997): 57–66.

10J. C. Bettis, J. M. Bizjak, and M. L. Lemmon, “Insider Trading in Derivative Securities: An Empirical Investigation of Zero Cost Collars and Equity Swaps by Corporate Insiders” (SSRN Working Paper 167189, 1999).

386 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

N U M B E R W A T C H

Analyst following by sector: Take a look at the number of analysts who follow the typical company, by sector, for the United States.

W h o D o A n a l y s t s F o l l o w ? The number of analysts tracking firms varies widely across firms. At one extreme are firms like Apple, GE, Google, and Microsoft that are followed by dozens of analysts. At the other extreme, there are hundreds of firms that are not followed by any analysts. Why are some firms more heavily followed than others? These seem to be some of the determinants:

Market capitalization. The larger the market capitalization of a firm, the more likely it is to be followed by analysts.

Institutional holding. The greater the percentage of a firm’s stock that is held by institutions, the more likely it is to be followed by analysts. The open question, though, is whether analysts follow companies because institutions own them or whether institutions invest in companies that are more heavily tracked by analysts. Given that institutional investors are the biggest clients of equity research analysts, the causality probably runs both ways.

Trading volume. Analysts are more likely to follow liquid stocks. Here again, though, it is worth noting that the presence of analysts may play a role in increasing trading volume.

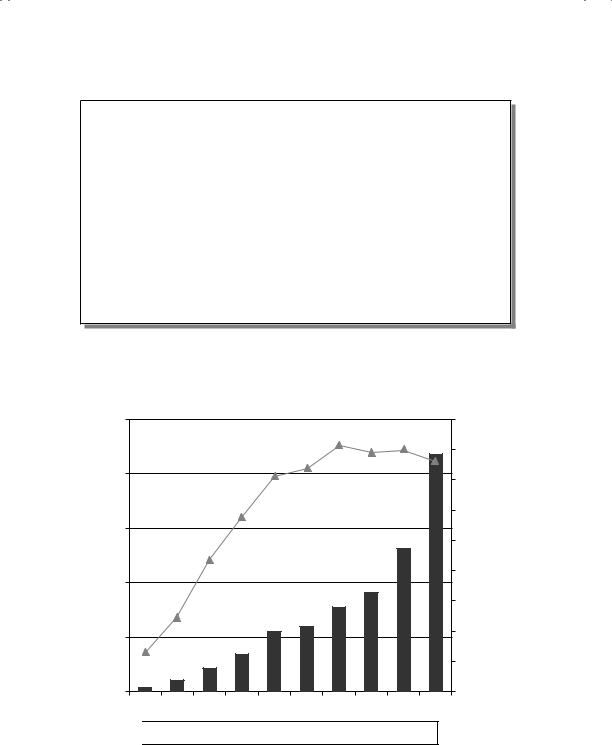

We capture all of these factors in Figure 10.6, where we classify firms into market value classes and look at the number of analysts and the institutional holding (as a percent of outstanding stock) in each class. The largest companies tend to be held more by institutions and followed by more equity research analysts.

S E L L - S I D E A N D B U Y - S I D E A N A L Y S T S :

A P R I M E R

There are thousands of financial analysts who try to value stocks, and most of them toil anonymously. The analysts who receive the most attention are the sell-side analysts who work for investment banks. Their research is primarily for external consumption and their

388 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

for the next quarter and for the next financial year. Presumably, this is where their access to company management and sector knowledge should generate an advantage. Thus, when analysts revise their forecasts upward or downward, they convey information to financial markets, and prices should react. In this section, we examine how markets react to analyst forecast revisions and whether there is a potential for investors to take advantage of this reaction.

The Information in Analyst Forecasts There is a simple reason to believe that analyst forecasts of growth in earnings should be better than using historical growth rates in earnings. Analysts, in addition to using historical data, can avail themselves of other information that may be useful in predicting future growth.

Firm-specific information that has been made public since the last earnings report. Analysts can use information that has come out about the firm since the last earnings report to make predictions about future growth. This information can sometimes lead to significant reevaluation of the firm’s expected earnings and cash flows.

Macroeconomic information that may impact future growth. The expected growth rates of all firms are affected by economic news on gross domestic product (GDP) growth, interest rates, and inflation. Analysts can update their projections of future growth as new information comes out about the overall economy and about changes in fiscal and monetary policy. Information, for instance, that shows the economy growing at a faster rate than forecast will result in analysts increasing their estimates of expected growth for cyclical firms.

Information revealed by competitors on future prospects. Analysts can also condition their growth estimates for a firm on information revealed by competitors on pricing policy and future growth. For instance, a negative earnings report by one automotive firm can lead to a reassessment of earnings for other automotive firms.

Private information about the firm. Analysts sometimes have access to private information about the firms they follow that may be relevant in forecasting future growth. In an attempt to restrict this type of information leakage, the SEC issued Regulation Fair Disclosure (Regulation FD) to prevent firms from selectively revealing information to a few analysts or investors. Outside the United States, however, firms routinely convey private information to analysts following them.

Public information other than earnings. Models for forecasting earnings that depend entirely upon past earnings data may ignore other publicly available information that is useful in forecasting future earnings. It has

Information Pays: Trading on News |

389 |

been shown, for instance, that other financial variables such as earnings retention, profit margins, and asset turnover are useful in predicting future growth. Analysts can incorporate information from these variables into their forecasts.

In summary, it is logical to expect that the resources that are expended in the care and feeding of equity research analysts provide a payoff on one of their primary tasks, forecasting earnings, if not in the long term, at least in the near term.

The Quality of Earnings Forecasts If analysts are indeed better informed than the rest of the market, the forecasts of growth from analysts should be better than estimates based on either historical growth or other publicly available information. But is this presumption justified? Are analyst forecasts of growth superior to other estimates?

The general consensus from studies that have looked at short-term forecasts (one quarter ahead to four quarters ahead) of earnings is that analysts provide better forecasts of earnings than models that depend purely upon historical data. The mean relative absolute error, which measures the absolute difference between the actual earnings and the forecast for the next quarter, in percentage terms, is smaller for analyst forecasts than it is for forecasts based on historical data.

Two studies shed further light on the value of analysts’ forecasts. An early study examined the relative accuracy of forecasts in the Earnings Forecaster, a publication from Standard & Poor’s that summarizes forecasts of earnings from more than 50 investment firms.13 This study measured the squared forecast errors by month of the year and computed the ratio of analyst forecast error to the forecast error from time-series models of earnings. It found that the time-series models actually outperform analyst forecasts from April until August, but underperform them from September through January. The authors of the study hypothesize that this is because there is more firm-specific information available to analysts during the latter part of the year. A later study compares consensus analyst forecasts from the Institutions Brokers Estimate System (I/B/E/S) with time-series forecasts from one quarter ahead to four quarters ahead.14 The analyst forecasts outperform

13T. Crichfield, T. Dyckman, and J. Lakonishok, “An Evaluation of Security Analysts Forecasts,” Accounting Review 53 (1978): 651–668.

14P. O’Brien, “Analyst’s Forecasts as Earnings Expectations,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 10 (1988): 53–83.

Number of Analysts

Number of Analysts  Institutional Holding (as %)

Institutional Holding (as %)