aswath_damodaran-investment_philosophies_2012

.pdf

452 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

with different voting rights, in the United States from 1993 to 2006 uncovered at least 3,687 cases where the bid price of one class of shares exceeded the ask price of the other class by at least 1 percent. Buying the cheaper class and selling the more expensive one generated excess returns in excess of 30 percent a year, after adjusting for cost of the bid-ask spread.12

N U M B E R W A T C H

Most widely traded American depositary receipts (ADRs): Take a look at the 50 most widely traded ADRs on the U.S. market.

D e p o s i t a r y R e c e i p t s Many Latin American, Asian, and European companies have American depositary receipts (ADRs) listed on the U.S. market. These depositary receipts create a claim equivalent to the one you would have had if you had bought shares in the local market and should therefore trade at a price consistent with the local shares. What makes them different and potentially riskier than the stocks with dual listings is that ADRs are not always directly comparable to the common shares traded locally—one ADR on Telmex, the Mexican telecommunications company, is convertible into 20 Telmex shares. In addition, converting an ADR into local shares can be both costly and time consuming. In some cases, there can be differences in voting rights as well. In spite of these constraints, you would expect the price of an ADR to closely track the price of the shares in the local market, albeit with a currency overlay since ADRs are denominated in dollars.

In a study that looks at the link between ADRs and local shares, Kin, Szakmary, and Mathur conclude that about 60 to 70 percent of the variation in ADR prices can be attributed to movements in the underlying share prices and that ADRs overreact to events in the U.S. market and underreact to changes in exchange rates and information about the underlying stock.13 However, they also conclude that investors cannot take advantage of the pricing errors in ADRs because convergence does not occur quickly or in predictable ways. With a longer time horizon and/or the capacity to convert

12P. Schultz and S. Shive, “Mispricing of Dual-Class Shares: Profit Opportunities, Arbitrage and Trading” (SSRN Working Paper 1338885, 2009).

13M. Kin, A. C. Szakmary, and I. Mathur, “Price Transmission Dynamics between ADRs and Their Underlying Foreign Securities,” Journal of Banking and Finance 24 (2000): 1359–1382.

A Sure Profit: The Essence of Arbitrage |

453 |

ADRs into local shares, though, you should be able to take advantage of significant pricing differences.

Studies that have looked at ADRs on stocks in a series of emerging markets, including Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Mexico, seem to arrive at common conclusions. There are often persistent deviations from price parity, and there seems to be a potential for excess returns, sometimes of significant magnitude, for investors who exploit unusually large price divergences.14 Every one of these studies also sounds notes of caution: convergence can sometimes be slow in coming, there are high transaction costs, and illiquidity in the local market can be a serious concern. Studies that have looked at developed markets such as Germany, Canada, and the United Kingdom also document occasional price differences between the local listing and the ADR, though the differences tend to be smaller and price convergence occurs more quickly.15

C l o s e d - E n d F u n d s

In a conventional mutual fund, the number of shares increases and decreases as money comes into and leaves the fund, and each share is priced at net asset value (NAV)—the market value of the securities of the fund divided by the number of shares. Closed-end mutual funds differ from other mutual funds in one very important respect. They have a fixed number of shares that trade in the market like other publicly traded companies, and the market price can be different from the net asset value.

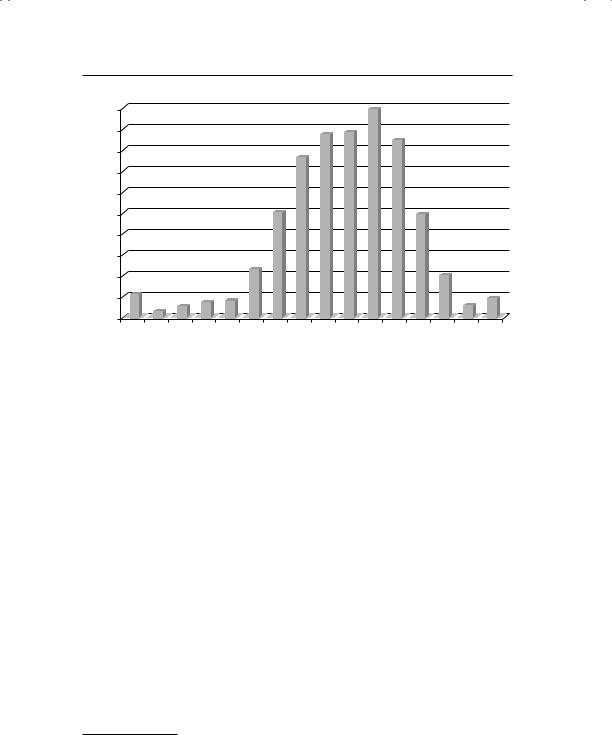

In both the United States and the United Kingdom, closed-end mutual funds have shared a common characteristic. When they are created, the price is usually set at a premium on the net asset value per share. As closed-end funds trade, though, the market price tends to drop below the net asset value and stay there. Figure 11.7 provides the distribution of premiums and discounts (computed by comparing the net asset value to the market price) for all closed-end funds in the United States in November 2011.

14For Argentina and Chile, see R. Rabinovitch, A. C. Silva, and R. Susmel, “Returns on ADRs and Arbitrage in Emerging Markets,” Emerging Markets Review 4 (2003): 225–328; for Mexico, see S. Koumkwa and R. Susmel, “Arbitrage and Convergence: Evidence from Mexican ADRs” (SSRN Working Paper, 2005); for Brazil, see O. R. de Mederos and M. E. de Lima, “Brazilian Dual-Listed Stocks, Arbitrage and Barriers” (SSRN Working Paper, 2007); for India, see S. Majumdar, “A Study of International Listing by Firms of Indian Origin” (SSRN Working Paper, 2007).

15See C. Eun and S. Sabberwal, “Cross-Border Listing and Price Discovery: Evidence from U.S. Listed Canadian Stocks,” Journal of Finance 58 (2002): 549–577; K. A. Froot and E. Dabora, “How Are Stock Prices Affected by the Location of Trade?”

Journal of Financial Economics 53 (1999): 189–216.

456 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

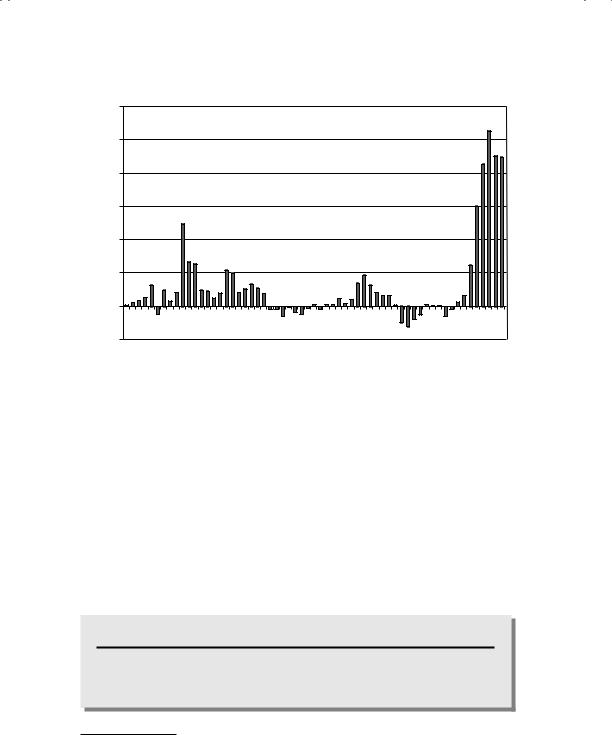

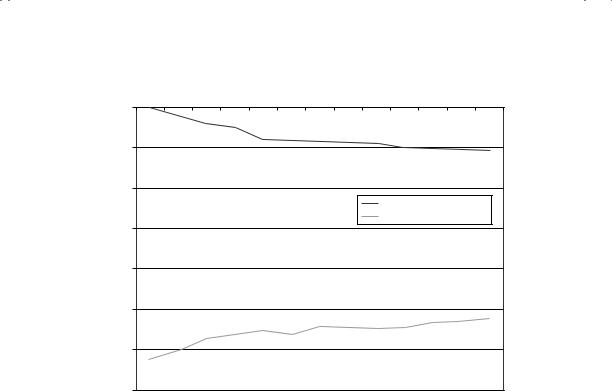

What about the strategy of buying discounted funds and hoping that the discount disappears? This strategy is clearly not riskless, but it does offer some promise. In one of the first studies of this strategy, Thompson studied closed-end funds from 1940 to 1975 and reports that you could earn an annualized excess return of 4 percent from buying discounted funds.18 A later study reports excess returns from a strategy of buying closed-end funds whose discounts had widened and selling funds whose discounts had narrowed—a contrarian strategy applied to closed-end funds.19 Extending the analysis, Pontiff reports that closed-end funds with a discount of 20 percent or higher earn about 6 percent more than other closed-end funds.20 These, as well as studies in the United Kingdom, seem to indicate a strong mean-reversion component to discounts at closed-end funds. Figure 11.9, which is from a study of the discounts on closed-end funds in the United Kingdom, tracks relative discounts on the most discounted and least discounted funds over time.

Note that the discounts on the most discounted funds decrease whereas the discounts on the least discounted funds increase, and the difference narrows over time.

Reviewing all of the evidence, it is clear that if there are profits to be made from investing in closed-end funds, they are neither riskless nor particularly large. Many closed-end funds trade at permanent discounts on their net asset values, and arbitrage opportunities are uncommon.

C o n v e r t i b l e a n d C a p i t a l S t r u c t u r e A r b i t r a g e

In both convertible and capital structure arbitrage, investors attempt to take advantage of relative mispricing of a firm’s different security offerings. In convertible arbitrage, the focus is on securities that have options embedded in them. Thus, when companies have convertible bonds or convertible preferred stock outstanding in conjunction with common stock, warrants, preferred stock, and conventional bonds, it is entirely possible that you could find one of these securities mispriced relative to the others, and be able to construct a low-risk strategy by combining two or more of the securities in a portfolio.

18Rex Thompson, “The Information Content of Discounts and Premiums on ClosedEnd Fund Shares,” Journal of Financial Economics 6 (1978): 151–186.

19Seth C. Anderson, “Closed-End Funds versus Market Efficiency,” Journal of Portfolio Management 13 (1986): 63–65.

20Jeffrey Pontiff, “Costly Arbitrage: Evidence from Closed-End Funds,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (1996): 1135–1151.

A Sure Profit: The Essence of Arbitrage |

457 |

|

0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Funds |

–10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Least Discounted Funds |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most Discounted Funds |

||||

on |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

–15% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discount |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–20% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–25% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–30% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

–35% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

Months after Ranking Date

F I G U R E 1 1 . 9 Discounts on Most Discounted and Least Discounted Funds over Time

Source: E. Dimson and C. Minio-Kozerski, “Closed-End Funds: A Survey” (working paper, London Business School, 1998).

In a simple example, note that since the conversion option is a call option on the stock, you could construct a synthetic convertible bond by combining holdings in the common stock of the company, a riskless investment, and a straight bond issued by the firm. Once you can do this, you can take advantage of differences between the pricing of the convertible bond and synthetic convertible bond and potentially make profits. In the more complex forms, when you have warrants, convertible preferred, and other options trading simultaneously on a firm, you could look for options that are mispriced relative to each other, and then buy the cheaper option and sell the more expensive one.

In practice, there are several possible impediments. First, many firms that issue convertible bonds do not have straight bonds outstanding, and you have to substitute a straight bond issued by a company with similar default risk. Second, companies can force conversion of convertible bonds, which can wreak havoc on arbitrage positions. Third, convertible bonds have long maturities. Thus, there may be no convergence for long periods,

458 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

and you have to be able to maintain the arbitrage position over these periods. Fourth, transaction costs and execution problems (associated with trading the different securities) may prevent arbitrage.

In capital structure arbitrage, you cast a wider net and look to see if a company’s debt is mispriced relative to its equity. Thus, for a distressed firm, if debt is being underpriced by bond investors while stock is being overpriced by equity investors, you would buy bonds and sell stock in the same company, hoping to gain from a convergence. The growth of the credit default swap (CDS) market has added another dimension to capital structure arbitrage. In its typical form, investors estimate what the theoretical CDS spread for a company should be, based on the stock price and how much debt the firm has, and compare this spread to the actual price for a CDS on that company in the market; if the CDS is priced too low, they buy the CDS; if it is priced too high, they sell it.21

The evidence on whether this strategy delivers risk-adjusted returns over time is mixed. A study of 135,759 CDS spreads across 261 different issuers from 2001 to 2005 found that while the strategy delivered profits at the portfolio level, individual trades were exposed to significant risk, especially from large movements in the CDS spreads.22 Another study that tried alternate structural models to estimate the correct CDS spread came to the conclusion that the structural models did well at forecasting changes in the CDS spread and that investors could earn significant excess returns, with those returns increasing for lower-credit-quality companies.

D e t e r m i n a n t s o f S u c c e s s

Studies that have looked at closed-end funds, dual-listed stocks, and the relative pricing of a firm’s securities all seem to conclude that there are pockets of inefficiency that can exploited to make money. However, there is residual risk in all of these strategies, arising sometimes from the fact that the assets are not perfectly identical (convertibles versus synthetic convertibles) or because there are no mechanisms for forcing the prices to converge (closed-end funds).

21There are several structural models that can be used to make this estimate. Many of them use variants of a pricing model developed by Merton, where equity is treated as a call option on the company and an option pricing model is used to extract the correct values for equity and the appropriate credit spread for debt. See R. C. Merton, “On the Pricing of Corporate Debt: The Risk Structure of Interest Rates,” Journal of Finance 29 (1974): 449–470.

22F. Yu, “How Profitable Is Capital Structure Arbitrage?” (SSRN Working Paper 687436, 2005).