aswath_damodaran-investment_philosophies_2012

.pdf

390 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

the time-series model for one-quarter-ahead and two-quarters-ahead forecasts, do as well as the time-series model for three-quarters-ahead forecasts, and do worse than the time-series model for four-quarters-ahead forecasts. Thus, the advantage gained by analysts from firm-specific information seems to deteriorate as the time horizon for forecasting is extended.

Dreman and Berry examined analyst forecasts from 1974 to 1991 and found that in more than 55 percent of the forecasts examined, analyst estimates of earnings were off by more than 10 percent from actual earnings.15 One potential explanation given for this poor forecasting is that analysts are routinely over optimistic about future growth. Chopra finds that a great deal of this forecast error comes from the failure of analysts to consider large macroeconomic shifts. In other words, analysts tend to overestimate growth at the peak of a recovery and underestimate growth in the midst of a recession.16 A study that compares analyst forecast errors across seven countries finds, not surprisingly, that analysts are more accurate and less biased in countries that mandate more financial disclosure.17

Most of these studies look at short-term forecasts (usually the next quarter), and there is little evidence to suggest that analysts provide superior forecasts of earnings when the forecasts are over the long term (three or five years). A study by Cragg and Malkiel compared long-term forecasts by five investment management firms in 1962 and 1963 with actual growth over the following three years to conclude that analysts were poor long-term forecasters.18 This view was contested in a later study by Vander Weide and Carleton, who found that the consensus predictions of five-year growth from analysts were superior to historically oriented growth measures in predicting future growth.19 In general, though, only a small proportion of analysts who follow firms make long-term forecasts.

There is an intuitive basis for arguing that analyst predictions of growth rates must be better than time-series or other historical-data-based models simply because they use more information. The evidence indicates, however,

15D. N. Dreman and M. Berry, “Analyst Forecasting Errors and Their Implications for Security Analysis,” Financial Analysts Journal (May/June 1995): 30–41.

16V. K. Chopra, “Why So Much Error in Analyst Forecasts?” Financial Analysts Journal (November–December 1998): 35–42.

17H. N. Higgins, “Analyst Forecasting Performance in Seven Countries,” Financial Analysts Journal 54 (May/June 1998): 58–62.

18J. G. Cragg and B. G. Malkiel, “The Consensus and Accuracy of Predictions of the Growth of Corporate Earnings,” Journal of Finance 23 (1968): 67–84.

19J. H. Vander Weide and W. T. Carleton, “Investor Growth Expectations: Analysts vs. History,” Journal of Portfolio Management 14 (1988): 78–83.

Information Pays: Trading on News |

391 |

that this superiority in forecasting is surprisingly small for long-term forecasts and that past growth rates play a significant role in determining analyst forecasts.

Market Reaction to Earnings Forecast Revisions In Chapter 7, we considered the price momentum strategies in which investors buy stocks that have gone up the most in recent periods, expecting the momentum to carry forward into future periods. You could construct similar strategies based on earnings momentum. While some of these strategies are based purely on earnings growth rates, most of them are based on how earnings measure up to analyst expectations. In fact, one strategy is to buy stocks where analysts are revising earnings forecasts upward, and hope that stock prices follow these earnings revisions.

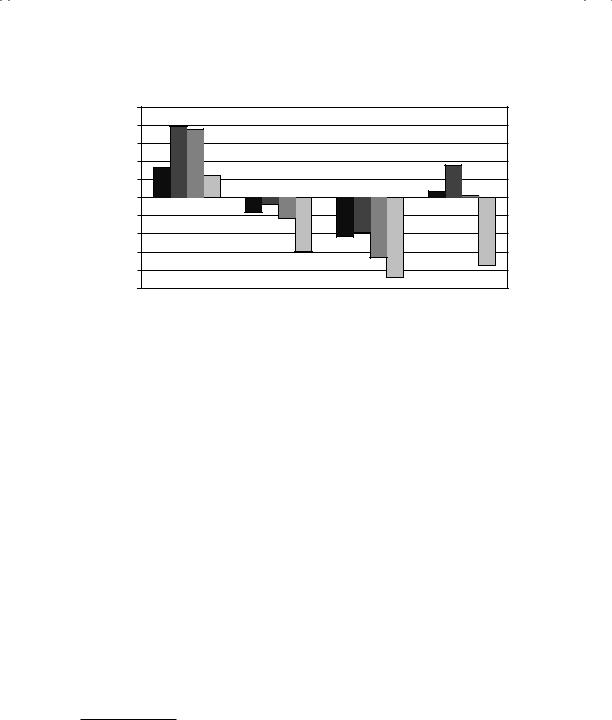

A number of studies in the United States conclude that it is possible to use forecast revisions made by analysts to earn excess returns. In one of the earliest studies of this phenomenon, Givoly and Lakonishok created portfolios of 49 stocks in three sectors based on earnings revisions, and reported earning an excess return on 4.7 percent over the following four months on the stocks with the most positive revisions.20 Hawkins, Chamberlin, and Daniels reported that a portfolio of stocks with the 20 largest upward revisions in earnings on the I/B/E/S database would have earned an annualized return of 14 percent, as opposed to the index return of only 7 percent.21 In another study, Cooper, Day, and Lewis reported that much of the excess returns is concentrated in the weeks around the revision (1.27 percent in the week before the forecast revision, and 1.12 percent in the week after), and that analysts that they categorize as leaders (based on timeliness, impact, and accuracy) have a much greater impact on both trading volume and prices.22 In 2001, Capstaff, Paudyal, and Rees expanded the research to look at earnings forecasts in other countries and concluded that you could have earned excess returns of 4.7 percent in the United Kingdom, 2 percent in France, and 3.3 percent in Germany from buying stocks with the most positive revisions.23

20D. Givoly and J. Lakonishok, “The Quality of Analysts’ Forecasts of Earnings,”

Financial Analysts Journal 40 (1984): 40–47.

21E. H. Hawkins, S. C. Chamberlin, and W. E. Daniel, “Earnings Expectations and Security Prices,” Financial Analysts Journal (September/October 1984): 20–38.

22R. A. Cooper, T. E. Day, and C. M. Lewis, “Following the Leader: A Study of Individual Analysts Earnings Forecasts,” Journal of Financial Economics 61 (2001): 383–416.

23J. Capstaff, K. Paudyal, and W. Rees, “Revisions of Earnings Forecasts and Security Returns: Evidence from Three Countries” (SSRN Working Paper 253166, 2000).

Information Pays: Trading on News |

393 |

A n a l y s t R e c o m m e n d a t i o n s The centerpieces of analyst reports are the recommendations that they make on stock, and these range from very positive (strong buy) to very negative (strong sell), with intermediate positions (weak buys, weak sells). You would expect stock prices to react to changes in analyst recommendations, if for no other reason than for the fact that some investors will follow these recommendations, pushing up stock prices on buy recommendations and pushing them down on sell recommendations. In this section, we consider some key empirical facts about analyst recommendations first and then consider how markets react to these recommendations. We close with an analysis of whether investors can use analyst recommendations to make money in the short term and the long term.

The Recommendation Game There are four empirical facts that need to be laid on the table about recommendations before we start examining how markets react to them.

1.If we categorize analyst recommendations into buy, sell, and hold, the overwhelming number are buy recommendations. In 2011, for instance, buy recommendations outnumbered sell recommendations for U.S. stocks by a 7 to 1 margin, but that was a marked improvement over the 25 to 1 margin that we saw in the boom market of the 1990s. While there are many reasons for this bias, the most significant one is that analysts who issue sell recommendations find themselves shunned not only by the companies in question but sometimes by the brokerage houses that they work for.

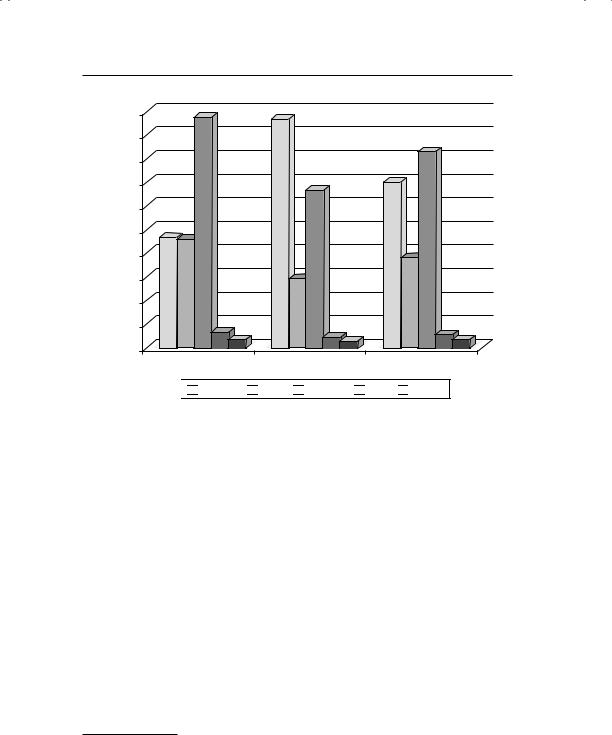

2.Part of the reason for this imbalance between buy and sell recommendations is that analysts often have many more layers beyond buy, sell, and hold. Some investment banks, for instance, have numerical rating systems in which stocks are classified from 1 to 5 (as is the case with Value Line), whereas others break buy and sell recommendations into subclasses (strong buy, weak buy). What this allows analysts to do is not only rate stocks on a finer scale, but also send sell signals without ever saying the word (sell). Thus, an analyst downgrading a stock from a strong buy to a weak buy is suggesting that investors sell the stock. In November 2011, for instance, we looked at the recommendations made by analysts on U.S. companies, categorized into five groups: from highest (strong buy or equivalent) to lowest (strong sell or equivalent); the numbers are presented in Figure 10.7.

Note that the positive recommendations vastly outnumber negative recommendations, and that the skew toward the positive is greater for small firms than for large ones.

Information Pays: Trading on News |

397 |

overlook the connections between analysts and the firms that they analyze and pay a significant price for the omission.28

Potential and Perils of Analyst Recommendations Can you make money off analyst recommendations? The answer seems to be yes, at least in the short term. Even if there were no new information contained in recommendations, there is the self-fulfilling prophecy created by clients who trade on these recommendations, pushing up stock prices after buy recommendations and pushing them down after sell recommendations.29 If this is the only reason for the stock price reaction, though, the returns are not only likely to be small but could very quickly dissipate, leaving you with large transaction costs and little to show as excess returns. In fact, that is the conclusion that Barber, Lehavy, McNichols, and Trueman arrive at in their study of whether investors can profit from following analysts.30

To incorporate analyst recommendations into an investment strategy, you need to adopt a more nuanced approach.

You should begin by identifying the analysts who not only are the most influential but also have the most content (private information) in their recommendations. Recommendations that are backed up by numbers and a solid story have more heft to them than recommendations that do not.

Optimally, you would want to screen out analysts where the potential conflicts of interest are too large for the recommendations to be unbiased. Since that will leave you with a relatively short list, you should also pay particular attention to recommendations that go against the grain (i.e., a sell recommendation from a normally bullish analyst or a buy recommendation from an analyst known for a bearish view).

28In June 2002, Merrill Lynch agreed to pay $100 million to settle with New York State, after the state uncovered e-mails sent by Henry Blodget, Merrill’s well-known Internet analyst, that seemed to disparage stocks internally as he was recommending them to outside clients. The fact that many of these stocks were being taken to the market by Merrill added fuel to the fire. Merrill agreed to make public any potential conflicts of interest it may have on the firms followed by its equity research analysts.

29This can be a significant factor. When the Wall Street Journal publishes its Dartboard column, it reports on the stocks being recommended by the analysts its picks. These stocks increase in price by about 4 percent in the two days after they are picked but reverse themselves in the weeks that follow.

30B. Barber, R. Lehavy, M. NcNichols, and B. Trueman, “Can Investors Profit from the Prophets? Security Analyst Recommendations and Stock Returns,” Journal of Finance 56 (2001): 531–563.

398 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

You should invest based on the recommendations, preferably at the time the recommendations are made.31

Assuming that you still attach credence to the views of the recommending analysts, you should watch analysts for signals that they have changed or are changing their minds. Since these signals are often subtle, you can easily miss them.

F I N D I N G T H E B E S T A N A L Y S T S

How does one go about finding the best analysts following a stock? You could go with the analysts chosen in popularity contests, where other analysts and/or portfolio managers vote for the “best” analysts. One example is the All-America analyst team from Institutional Investor, where the star analysts are picked in each sector. But do not fall for the hype. The highest-profile analysts on this list are not always the best, and some are notorious for self-promotion. The best sources of information on analysts tend to be outside services without an ax to grind. The Wall Street Journal has a special section on sell-side equity

research analysts, where it evaluates analysts on the quality of their recommendations and ranks them on that basis. There are a few online services that track equity research forecasts and recommendations and report on how close actual earnings numbers were to their forecasts.

There are qualitative factors to consider as well. Analysts who have clear, well-thought-out analyses that show a deep understanding of the businesses that they analyze should be given more weight that analysts who make spectacular recommendations based on surfacelevel assessments. Most importantly, good analysts should be just as willing to stand up to the management of companies and disagree with them (and issue sell recommendations).

T R A D I N G O N P U B L I C I N F O R M A T I O N

Most of us do not have access to private information about firms, but we all share access to public information about a firm. Some of this public

31This might not be your choice to make, since analysts reveal their recommendations first to their clients. If you are not a client, you will often learn about the recommendation only after the clients have been given a chance to take positions on the stock.

Information Pays: Trading on News |

399 |

information takes the form of periodic earnings reports and dividend announcements, made four times every year by most firms in the United States and less frequently elsewhere, and some of it is news made by the firm when it announces that it is taking over another firm (or being taken over) or making a major investment or divestiture. In some cases, the information comes from a regulatory authority governing the firm’s fortunes, as is the case when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announces that it has approved (or not approved) a drug for treatment. In each of these cases, we would expect the stock price to react to the news contained in the announcement. If the market reaction is appropriate, there is little that we can do to make money off the news, but if the market reaction is not appropriate, we may be able to exploit it with specific trading strategies.

E a r n i n g s A n n o u n c e m e n t s

When firms make earnings announcements, they convey information to fi- nancial markets about their current and future prospects. The magnitude of the information in the report, and the size of the market reaction to it, should depend on how much the earnings report exceeds or falls short of investor expectations. In an efficient market, there should be an instantaneous reaction to the earnings report if it contains surprising information, and prices should increase following positive surprises and move down following negative surprises.

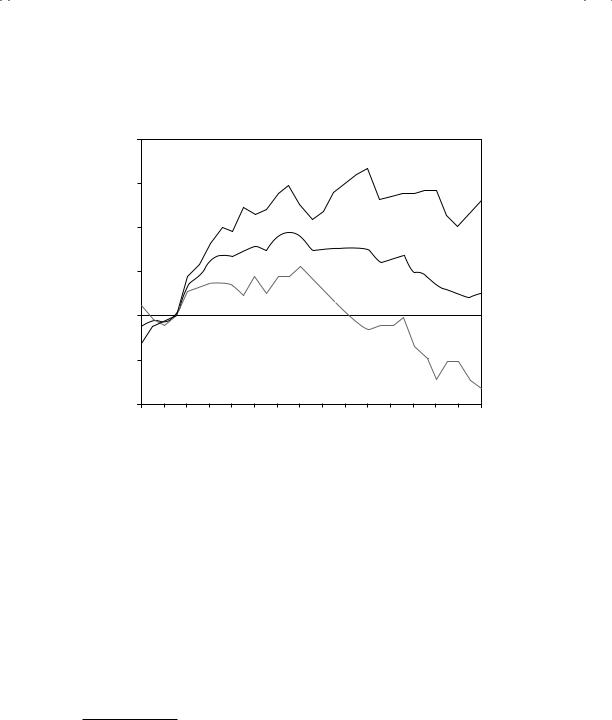

E a r n i n g s S u r p r i s e s a n d P r i c e R e a c t i o n Since actual earnings are compared to investor expectations, one of the key parts of an earnings event study is the measurement of these expectations. Some of the earlier studies of the phenomenon used earnings from the same quarter in the prior year as a measure of expected earnings; that is, firms that report increases in quarter-to-quarter earnings provide positive surprises and those that report decreases in quarter-to-quarter earnings provide negative surprises. In more recent studies, analyst estimates of earnings have been used as a proxy for expected earnings and have been compared to the actual earnings. Figure 10.10 is a graph of price reactions to earnings surprises, classified on the basis of magnitude into different classes, from most negative earnings reports to most positive earnings reports.32

32The original study of this phenomenon was in R. Ball and P. Brown, “An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers, Journal of Accounting Research 6 (1968): 159–178. That study was updated by Bernard and Thomas (1989), with daily data around quarterly earnings announcements. (V. Bernard and J. Thomas,

Highest

Highest

High

High

Neutral

Neutral

Low

Low

Lowest

Lowest