- •Table of Contents

- •Front matter

- •Copyright

- •Preface to the twelfth edition

- •Preface to the eleventh edition

- •Preface to the tenth edition

- •Acknowledgements

- •Chapter 1. Introduction to regional anatomy

- •2. Upper limb

- •Part two. Shoulder

- •Part three. Axilla

- •Part four. Breast

- •Part five. Anterior compartment of the arm

- •Part six. Posterior compartment of the arm

- •Part eight. Posterior compartment of the forearm

- •Part nine. Wrist and hand

- •Part ten. Summary of upper limb innervation

- •Part eleven. Summary of upper limb nerve injuries

- •Part twelve. Osteology of the upper limb

- •Chapter 3. Lower limb

- •Part two. Medial compartment of the thigh

- •Part three. Gluteal region and hip joint

- •Part four. Posterior compartment of the thigh

- •Part five. Popliteal fossa and knee joint

- •Part six. Anterior compartment of the leg

- •Part seven. Dorsum of the foot

- •Part eight. Lateral compartment of the leg

- •Part nine. Posterior compartment of the leg

- •Part ten. Sole of the foot

- •Part eleven. Ankle and foot joints

- •Part twelve. Summary of lower limb innervation

- •Part thirteen. Summary of lower limb nerve injuries

- •Part fourteen. Osteology of the lower limb

- •Chapter 4. Thorax

- •Part one. Body wall

- •Part three. Thoracic cavity

- •Part five. Anterior mediastinum

- •Part eight. Pleura

- •Chapter 5. Abdomen

- •Part two. Abdominal cavity

- •Part nine. Spleen

- •Part eleven. Kidneys, ureters and suprarenal glands

- •Part twenty. Female urogenital region

- •Chapter 6. Head and neck and spine

- •Part three. Prevertebral region

- •Part eleven. Mouth and hard palate

- •Part fifteen. Lymph drainage of head and neck

- •Part twenty-two. Vertebral canal

- •Chapter 7. Central nervous system

- •Part two. Brainstem

- •Part three. Cerebellum

- •Part four. Spinal cord

- •Part five. Development of the spinal cord and brainstem nuclei

- •Chapter 8. Osteology of the skull and hyoid bone

- •Part two. Hyoid bone

- •Biographical notes

- •Index

Chapter 8. Osteology of the skull and hyoid bone

Part one. Skull

The term skull includes the mandible, and the cranium is the skull without the mandible. The cranial cavity has a roof or cranial vault, and a floor which is the base of the skull. The facial skeleton is the front part of the skull and includes the mandible (Figs 8.1 and 8.2).

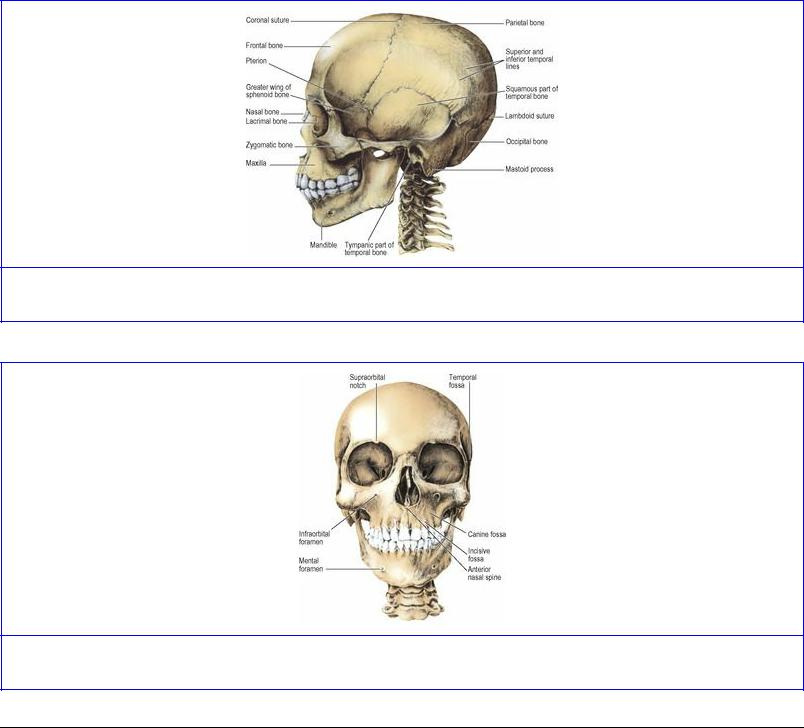

Figure 8.1 Left side of the skull.

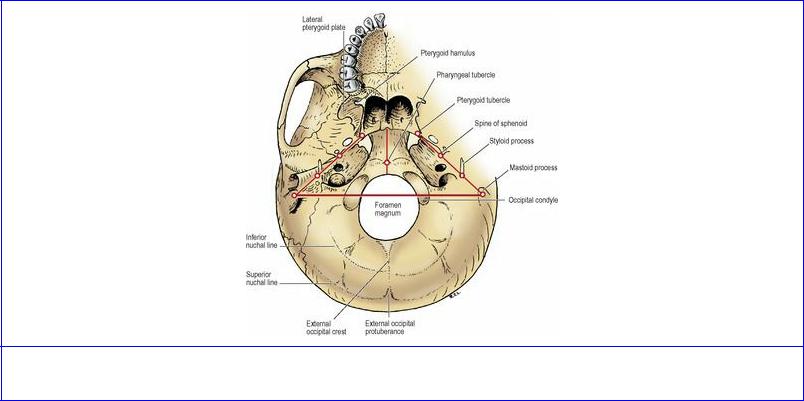

Figure 8.2 Anterior view of the skull.

External features

Superior view

Anteriorly the frontal bone articulates with the pair of parietal bones at the coronal suture, which runs transversely. The original two halves of the developing frontal bone occasionally fail to fuse, leaving a midline metopic suture. The midline meeting place of the frontal and parietal bones is the bregma, the site of the anterior fontanelle (see Fig. 1.28, p. 32). Behind the bregma the parietal bones articulate in the midline sagittal suture. On either side of the posterior part of this suture a foramen

often perforates each parietal bone, through which an emissary vein connects the superior sagittal sinus with scalp veins. The sagittal suture curves down to the lambda, at the apex of the occipital bone.

Posterior view

The lambda is the midline point where the sagittal suture meets the tortuous lambdoid suture between the squamous part of the occipital and the parietal bones (see Fig. 6.84, p. 431). Along these sutures small sutural (Wormian) bones are commonly found.

Some 6 cm below the lambda the occipital bone is projected into the external occipital protuberance, from which a ridge curves, convex upwards, towards the base of the mastoid process. This is the superior nuchal line (Fig. 8.3); gently convex upwards it lies at the junction of neck and scalp. It is the surface marking of the attachment of the tentorium cerebelli and the transverse sinus. Trapezius (medial third) and sternocleidomastoid (lateral half) are attached along the superior nuchal line. Splenius capitis is inserted into the lateral third of the line deep to sternocleidomastoid. Above this a faint, often imperceptible, highest nuchal line gives origin to occipitalis and the galea aponeurotica. Below the superior nuchal line the bone covers the cerebellar hemispheres and gives attachment to muscles at the back of the neck (see p. 430).

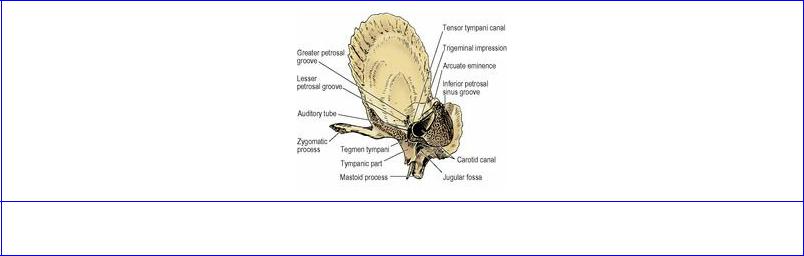

Figure 8.3 External surface of the base of the skull, with survey landmarks.

The mastoid region of the temporal bone articulates with the parietal and occipital bones, and the mastoid process projects down at the side. The suture between the mastoid and occipital bones is commonly perforated by a mastoid emissary foramen, for a vein which connects the sigmoid sinus with the posterior auricular vein.

Lateral view

To the lateral surface of the mastoid process is attached the sternocleidomastoid, with splenius and

longissimus capitis lying deep to it. In front of this is the external acoustic meatus. Above the meatus is a horizontal ridge, the supramastoid crest.

Above the crest the squamous part of the temporal bone extends up to articulate with the parietal bone. The curved anterior border of the squamous part continues to articulate with the parietal bone by its upper part while the lower part articulates with the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The coronal suture comes down along the side of the skull to reach the curved upper border of the greater wing of the sphenoid, which thus articulates posteriorly with the parietal bone and anteriorly with the frontal bone. The resulting H-shaped pattern of sutures in this region between frontal, parietal, temporal and sphenoid bones is termed the pterion (Fig. 8.1).

The supramastoid crest is projected forwards as the upper border of the zygomatic process of the temporal bone. The zygomatic arch is continued by the zygomatic bone. The frontal process of the zygomatic bone reaches up to meet the frontal bone at the frontozygomatic suture which is palpable in the living. The zygomatic bone has a sharp posterior border which continues up across the suture as a ridge on the frontal bone (Fig. 8.1). This ridge arches up and back and diverges into the superior and inferior temporal lines. The superior line fades posteriorly; the temporalis fascia is attached to it. The inferior temporal line curves down across the squamous temporal bone and turns forwards to join the supramastoid crest.

The temporal fossa is the area bounded by the superior temporal line, zygomatic arch and the frontal process of the zygomatic bone. The temporal fascia is attached above to the superior temporal line and below to the zygomatic arch. Temporalis arises from the inferior temporal line and the whole surface of the temporal fossa below it. The fossa is walled off anteriorly by the concave surface of the zygomatic bone which is here perforated by the zygomaticotemporal nerve.

The zygomatic arch is formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone and the temporal process of the zygomatic bone, which meet at an oblique suture near the front end of the arch. (The term ‘zygoma’ is best avoided; it means the arch, though it is often incorrectly used as a name for the zygomatic bone.) The masseter arises mainly from the lower border of the arch, while its posterior deep fibres arise from the medial surface of the arch. The parotidomasseteric fascia is also attached to the lower border of the arch. The arch is crossed in front of the external acoustic meatus by the auriculotemporal nerve and the superficial temporal vessels. Further forward the arch is crossed by the temporal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve.

The posterior part of the zygomatic process of the temporal bone is described as having anterior and posterior roots. The latter is the backward extension of the arch above the external auditory meatus, its upper border continuing into the supramastoid crest. The anterior root runs medially across the front of the mandibular fossa forming the articular eminence, which is part of the superior articular surface of the temporomandibular joint. Where the anterior root joins the zygomatic arch, the latter has a triangular projection pointing downwards. This is the articular tubercle to which the lateral ligament of the joint is attached.

The zygomatic bone forms the bony prominence of the cheek; it is perforated by the zygomaticofacial foramen for the zygomaticofacial nerve. Zygomaticus major arises from the surface of the zygomatic bone, and zygomaticus minor from the zygomaticomaxillary suture.

The posterior convexity of the maxilla curves backwards towards the lateral pterygoid plate, from which it is separated by the pterygomaxillary fissure. This is closed inferiorly by the pyramidal process (tubercle) of the palatine bone which is wedged between them (see Fig. 6.13, p. 352). The pterygopalatine fossa lies deep to the fissure.

The tuberosity of the maxilla is a bony prominence above the posterior surface of the last molar tooth. The buccinator arises from a linear strip on the maxilla, running forwards from here above the molar teeth. From the tuberosity a fibrous band, the pterygomaxillary ligament (see Fig. 6.13, p. 352), continues the origin of the buccinator to the tip of the hamulus. Deep to the buccinator is the vestibule of the mouth; superficial to it are the soft tissues of the face. From the tuberosity of the maxilla and the pyramidal process of the palatine bone the small superficial head of the medial pterygoid arises, overlapping the inferior head of the lateral pterygoid, which arises from the whole surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. The posterior convexity of the maxilla above the tuberosity shows two or more foramina for the posterior superior alveolar nerves and vessels.

The zygomatic process of the maxilla articulates with the zygomatic bone and with it forms an anterior pillar for the zygomatic arch. It is palpable through the cheek or the vestibule.

Anterior view

The frontal bone curves down to make the upper margins of the orbits (Fig. 8.2). Medially it goes down to meet the frontal process of each maxilla, between which it articulates with the nasal bones. Laterally it projects down as a zygomatic process to make the frontozygomatic suture with the zygomatic bone at the lateral margin of the orbit. The frontal bone occupies the upper third of the anterior view of the skull, the maxillae and mandible making the other two-thirds.

The nasal bones curve downwards and forwards from their articulation with the frontal bone. Each articulates with the frontal process of the maxilla, and they arch forward to meet in a midline suture. The lower border of each is notched by the external nasal nerve (which also grooves the posterior surface of the nasal bone). These free borders make with the two maxillae a pear-shaped piriform (anterior nasal) aperture (Fig. 8.2). In the nasal cavity the bony septum and the conchae of the lateral wall are visible. The two maxillae meet in a midline intermaxillary suture, and are projected forward as the anterior nasal spine at the lower margin of the nasal aperture. The canine root makes a ridge on the anterior surface of the maxilla, on either side of which are slight depressions, the medial one being the incisive fossa and the lateral the canine fossa, from which levator anguli oris arises and above which the anterior surface of the maxilla is perforated by the infraorbital foramen. Levator labii superioris arises from the lower margin of the orbit above the foramen, from which the infraorbital nerve emerges between these muscles. The line of attachment of buccinator and that of levator anguli oris on the body of the maxilla mark the middle of the maxillary sinus, which lies with its lower half deep to the vestibule and its upper half deep to the soft tissues of the face. The supraorbital notch, infraorbital foramen and mental foramen lie all three in a vertical line, which passes between the two lower premolar teeth. The osteology of the orbital walls and margin is described on page 397.

Inferior view

The area behind the foramen magnum consists of the squamous part of the occipital bone. The superior nuchal line lies in a curve concentric with the foramen magnum. Halfway between them the

inferior nuchal line is concentric with both. The external occipital crest, in the midline between the external occipital protuberance and the foramen magnum, bisects this area and gives attachment to the ligamentum nuchae. A rather vague line, radiating back and outwards from the foramen magnum, further bisects each half. Thus four areas are demarcated in each half (Fig. 8.3). There are two alongside the foramen magnum to which are attached rectus capitis posterior minor medially, and rectus capitis posterior major laterally (see Fig. 6.84, p. 431). Between superior and inferior nuchal lines semispinalis capitis is attached medially and superior oblique laterally.

One-third of the foramen magnum lies in front and two-thirds behind a line joining the tips of the mastoid processes. The occipital condyles have the reverse proportions; two-thirds of the condyle lies in front of the line.

The foramen magnum is in the basilar part of the occipital bone (basiocciput). The fibrous dura mater is attached to the margins of the foramen as it sweeps down from the posterior cranial fossa. Within the tube of dura mater, the lower medulla with the vertebral and spinal arteries and the spinal roots of the accessory nerves traverse the foramen in the subarachnoid space (see Fig. 6.109, p. 452). Anteriorly the margin of the foramen gives attachment to the ligaments sweeping up from the axis. Adherent to dura mater is the tectorial membrane and in front of this is the vertical limb of the cruciform ligament (see Fig. 6.79, p. 427); in front again are the apical and the pair of alar ligaments of the dens of the axis. Most anteriorly is the attachment of the anterior atlanto-occipital membrane. The posterior atlanto-occipital membrane is attached to the posterior margin of the foramen magnum.

The occipital condyles are convex kidney-shaped surfaces, covered with hyaline cartilage, beside the front half of the foramen magnum. The two convexities make a ball-and-socket joint with the atlas. But the anteroposterior curve is more pronounced than the combined side to side curvature; so the ball is oval-shaped, like an egg lying on its side, and thus permits nodding and some abduction but no rotation. Behind the condyle is the shallow condylar fossa floored by thin bone, commonly perforated by the condylar canal, carrying an emissary vein from the sigmoid sinus to the suboccipital venous plexus. Above the occipital condyle is the hypoglossal canal for the hypoglossal nerve, which emerges medial to the jugular foramen.

The basiocciput extends forward from the foramen magnum and fuses with the basisphenoid. The pharyngeal tubercle is a slight bony prominence in front of the foramen magnum, marking the midline attachment of the pharyngobasilar fascia (see Fig. 6.35, p. 384) and the highest fibres of the superior constrictor. The attachment of the fascia extends on either side of the pharyngeal tubercle along a faint ridge, convex forwards. Behind this is the attachment of the prevertebral fascia, longus capitis and rectus capitis anterior in that order from before backwards immediately in front of the occipital condyle (see Fig. 6.8, p. 345).

The mastoid process is grooved on the deep aspect of its base by the digastric notch for the origin of the posterior belly of the digastric (see Fig. 6.35, p. 384). Medial to this notch a groove for the occipital artery indents the bone along the temporo-occipital suture. The length of the styloid process is very variable. The stylopharyngeus arises high up medially, the stylohyoid high up posteriorly, and the styloglossus low down in front. The stylohyoid ligament passes on from its tip. Between the bases of the styloid and mastoid processes is the stylomastoid foramen, transmitting the facial nerve and the stylomastoid branch of the posterior auricular artery with its accompanying vein. Medial to the

styloid process the petrous bone is deeply hollowed out to form the jugular fossa, which with the shallower jugular notch in the occipital bone forms the jugular foramen, and lodges the jugular bulb at the beginning of the internal jugular vein. The inferior petrosal sinus, the glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory nerves emerge through the foramen anteromedial to the vein.

Anterior to the jugular fossa the petrous part of the temporal bone is perforated by the carotid canal. The internal carotid artery enters here and turns forward into the bone. On the ridge of bone between the jugular fossa and the carotid canal is the canaliculus for the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Anterolateral to the carotid canal, at the margin of the petrous bone, is the opening of the bony part of the auditory tube. Levator palati arises from the rectangular area at the apex of the petrous within the attachment of the pharyngobasilar fascia. The tip of the petrous bone forms the posterior boundary of the foramen lacerum between the basiocciput and the body and greater wing of the sphenoid. The foramen lacerum is closed here in life by dense fibrous tissue that extends across from the periosteum of the adjacent bones, and is pierced only by a small emissary vein and a meningeal branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery.

Lateral to the jugular fossa, the tympanic part of the temporal bone forms the bony part of the external acoustic meatus. The tympanic part is C-shaped, open above, and the squamous part of the temporal bone completes the bony ring of the external acoustic meatus. The posterosuperior margin of the meatus has a small prominence, the suprameatal spine, and forms one boundary of the (MacEwen's) suprameatal triangle; the other boundaries are the supramastoid crest and a vertical line drawn upwards from the posterior margin of the meatus. The tympanic (mastoid) antrum lies 15 mm deep to the surface of the triangle.

Anterior to the tympanic plate, the squamous part of the temporal bone is hollowed into the mandibular fossa which, with the articular eminence in front, forms the upper articular surface of the temporomandibular joint (Fig. 6.19, p. 361). The squamotympanic fissure lies between the two parts, but medially they are separated by a thin flange of bone. This is the projecting margin of the tegmen tympani, part of the petrous bone that has turned down from the roof of the middle ear (Fig. 8.4). It divides the medial part of the squamotympanic fissure into the petrosquamous fissure in front, for the capsule of the jaw joint, and the petrotympanic fissure behind (see Fig. 6.35, p. 384), through the medial end of which emerges the chorda tympani. The nerve runs down in a groove on the medial surface of the spine of the sphenoid.

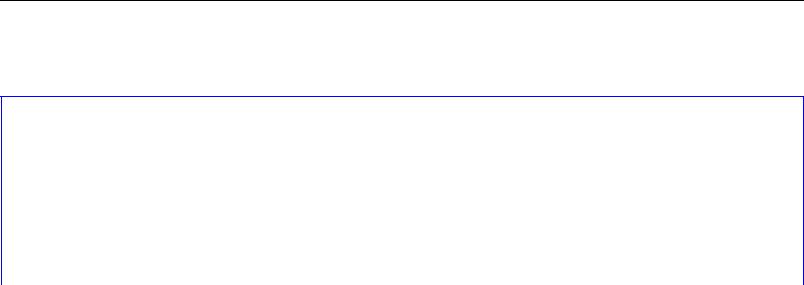

Figure 8.4 Right temporal bone, looking directly at the apex from the medial aspect.

A small triangular area of squamous bone in front of the articular eminence and the inferior aspect of the greater wing of the sphenoid form the roof of the infratemporal fossa. The upper head of lateral pterygoid arises from here. Anteriorly the inferior orbital fissure lies between the greater wing and the maxilla. The roof of the infratemporal fossa is pierced medially by the foramen ovale through which pass the mandibular nerve, its motor root and meningeal branch, the lesser petrosal nerve, the accessory meningeal artery and an emissary vein that connects the pterygoid plexus with the cavernous sinus. This vein may instead pass through a small venous foramen (of Vesalius) medial to the foramen ovale. The base of the spine of the sphenoid is perforated by the foramen spinosum for the middle meningeal vessels. The medial and lateral pterygoid plates project down from a common pterygoid process of the sphenoid at the base of the skull. The pterygoid tubercle projects back towards the foramen lacerum from the attachment of the medial pterygoid plate to the base of the skull. A line joining the tip of the mastoid process, styloid process, spine of the sphenoid and pterygoid tubercle lies at 45° to the sagittal plane (Fig. 8.3). The stylomastoid foramen lies behind the base of the styloid process, and the spine of the sphenoid overlies the opening in the petrous bone of the bony part of the auditory tube. The cartilaginous part of the tube lies along the above line, below the slit between the greater wing of the sphenoid and the apex of the petrous bone (see Fig. 6.35, p. 384). The foramen ovale perforates the greater wing of the sphenoid just lateral to the line, and the inferior opening of the carotid canal in the petrous temporal bone lies just medial to the line.

The medial pterygoid plate forms the most posterior part of the lateral wall of the nose. Its lower end has a small hook-like projection, the pterygoid hamulus (Fig. 8.3), around which the tendon of tensor palati turns. To its tip is attached the pterygomandibular raphe where the fibres of buccinator and superior constrictor interdigitate (see Fig. 6.13, p. 352). The expanded medial end of the cartilaginous auditory tube grooves the upper part of the posterior border of the medial pterygoid plate; below this the pharyngobasilar fascia and the superior pharyngeal constrictor are attached down to the hamulus. At its upper end, the posterior border splits into two edges which pass backwards and laterally enclosing the scaphoid fossa, that gives attachment to the tensor palati. The small pterygoid tubercle projects backwards medial to the scaphoid fossa, obscuring the posterior opening of the pterygoid canal that lies above it at the anterior end of the foramen lacerum. In the roof of the nose, the medial pterygoid plate has a small medial extension, the vaginal process (see Fig. 6.26, p. 370), which articulates above with the ala of the vomer and below with the sphenoidal process of the palatine bone. A small palatovaginal canal between these processes transmits the pharyngeal branches of the maxillary nerve and artery.

The lateral pterygoid plate extends back and laterally into the space of the infratemporal fossa. It gives attachment to the lower head of lateral pterygoid from its lateral surface, and to the deep head of medial pterygoid from its medial surface.

At the lateral and anterior margins of the hard palate the alveolar processes of the maxillae project downwards. Behind this projection in the anterior midline is the incisive fossa leading up into bilateral incisive foramina that open into the nasal cavity, and through which pass the greater palatine artery from below and the nasopalatine nerve from above. Medial to the third molar tooth on either side is the greater palatine foramen, between the horizontal plate of the palatine bone and the alveolar process of the maxilla. Further back are small multiple lesser palatine foramina in the pyramidal process of the palatine bone. Through the corresponding palatine foramina pass the greater and lesser palatine nerves and vessels. Medial to the greater palatine foramen is a low transverse

crest. The palatine aponeurosis is attached to the smooth part of the palatine bone behind the crest.

Internal features

The inner surface of the cranial vault shows a midline groove, widening as it is traced back, for the superior sagittal sinus. Pits in and lateral to the groove are the indentations of arachnoid granulations, those outside the sinus being in the lateral blood lakes. The grooves for the anterior and posterior branches of the middle meningeal vessels extend on to the side of the skull.

The internal surface of the base of the skull is in three levels, like the steps of a staircase: the anterior, middle and posterior cranial fossae. The anterior fossa lodges the frontal lobe and its floor is level with the upper margin of the orbit. The middle fossa lodges the temporal lobe and its floor is level with the upper border of the zygomatic arch. The posterior fossa lodges the brainstem and cerebellum and the attachment of its roof (the tentorium) lies at the upper limit of the neck muscles, attached to the outer aspect of the occipital bone.

The anterior cranial fossa extends as far back as the sharp posterior edge of the lesser wing of the sphenoid (see Fig. 6.101, p. 441). The orbital part of the frontal bone is the largest contributor to the anterior fossa. The frontal sinus invades a variable area at the anteromedial part of the roof of the orbit. Medially the frontal bone roofs in the ethmoidal sinuses and articulates with the cribriform plate. Anteriorly, a midline crest for the falx cerebri runs backwards from the front wall to a small pit, the foramen caecum, which is plugged by the fibrous tissue of the falx; in only 1% of subjects does a vein pass through the foramen, connecting nasal veins with the superior sagittal sinus. Just behind the foramen, the midline of the cribriform plate is projected up as a sharp triangle of bone, the crista galli, also for attachment of the falx. Alongside the anterior end of the crista galli is a slit through which the anterior ethmoidal nerve and vessels pass into the nasal cavity. The perforations in the cribriform plate are for the olfactory nerves. Behind the cribriform plate is the jugam (part of the body) of the sphenoid, which joins the two lesser wings and roofs the sphenoidal sinus.

The middle cranial fossa is butterfly-shaped. The small ‘body’ of the butterfly is the body of the sphenoid between the clinoid processes, while the ‘wings’ of the butterfly expand hugely into a concavity that extends out to the lateral wall of the skull and back to the upper border of the petrous bone. The body of the sphenoid is centrally hollowed out into the pituitary fossa, or sella turcica (‘Turkish saddle’), with a hump in front, the tuberculum sellae, which has a small elevation, the middle clinoid process, at each side (see Fig. 6.102, p. 444). Lateral to this a larger anterior clinoid process projects backwards from the medial ends of the lesser wings. At the back is a transverse ledge, the dorsum sellae (‘back of the saddle’); its upper border ends at each side as the posterior clinoid process.

A sheet of fibrous dura mater, the diaphragma sellae, sweeps across from the tuberculum sellae to the dorsum sellae, roofing the pituitary fossa. It is continuous laterally with the roof of the cavernous sinus, which lies on each side of the sphenoid body (see Fig. 6.103, p. 444). The diaphragma sellae is perforated centrally for the pituitary stalk, and the roof of each cavernous sinus is pierced anteriorly by the internal carotid artery, between the middle and anterior clinoid processes. A flange of dura mater, attached above to the medial and posterior clinoid processes, descends vertically between the cavernous sinus and the pituitary fossa, and sweeps medially to floor the fossa. The anterior and posterior clinoid processes give attachment to the free and attached margins, respectively, of the

tentorium cerebelli (see Fig. 6.101, p. 441).

In front of the tuberculum sellae is the chiasmatic sulcus, a groove on the upper surface of the sphenoid body. Despite the name of the groove, the optic chiasma lies at a higher level well behind it. The optic canals lie at the lateral ends of the groove, bounded by the two roots of the lesser wing and the body of the sphenoid. Each canal transmits an optic nerve, an ophthalmic artery and their meningeal sleeve.

The side of the body of the sphenoid is grooved by the internal carotid artery as it runs in the cavernous sinus from the foramen lacerum to the anterior clinoid process (see Fig. 6.102, p. 444). Lateral to this the floor of the middle fossa is made by the greater wing of the sphenoid and the petrous part of the temporal bone. Between the greater wing, the apex of the petrous bone and the side of the body of the sphenoid bone is the irregular foramen lacerum. The internal carotid artery emerges from the apex of the petrous bone to occupy the upper part of the foramen lacerum and then grooves the sphenoid. The posterior end of the lateral ridge of the groove in the sphenoid is often prominent as the lingula. Beneath the lingula is the posterior opening of the pterygoid canal, which is not visible from the middle cranial fossa. Lateral to the foramen lacerum the anterior surface of the apex of the petrous bone has a fossa, the trigeminal impression, occupied by the trigeminal ganglion (Fig. 8.4).

The upper margin of the apex of the petrous bone has a shallow groove made by the sensory root of the trigeminal nerve, with the small motor root below it. Lateral to this the upper border is grooved by the superior petrosal sinus, and to the lips of this narrow groove the tentorium cerebelli is attached, straddling the sinus.

The lateral part of the posterior wall of the middle fossa has a prominence, the arcuate eminence, which is made by the underlying anterior semicircular canal (see Fig. 6.105, p. 446). Medial and anterior to the arcuate eminence is the groove for the greater petrosal nerve, which passes obliquely into the foramen lacerum; as it does so, the nerve lies beneath the trigeminal ganglion (see Fig. 6.101, p. 441). Parallel and anterolateral to this is a small groove made by the lesser petrosal nerve; this groove is directed towards the foramen ovale.

Just in front of the petrous part of the temporal bone, the greater wing of the sphenoid is perforated by the small foramen spinosum and, anteromedial to this, by the much larger foramen ovale. The structures that pass through the foramen ovale have been described on page 507. From the foramen spinosum a groove for the middle meningeal vessels runs anterolaterally and splits into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior groove frequently enters a bony canal in the region of the pterion.

In front of the foramen ovale is the foramen rotundum, which opens forwards into the pterygopalatine fossa. It transmits the maxillary nerve.

Anteriorly the greater wing of the sphenoid fails to meet the lesser wing; the slit between them is the superior orbital fissure. Lateral to the line of the foramen rotundum this is closed by fibrous dura mater. Medial to the line of the foramen rotundum the medial end of the superior orbital fissure is open for the receipt of venous drainage from the orbit into the cavernous sinus and for the passage of nerves that run along the sinus into the orbit. The sphenoparietal sinus runs medially just below the margin of the lesser wing to enter the roof of the cavernous sinus.

The posterior cranial fossa, deeply concave, lies above the foramen magnum. Anteriorly, its upper limit is the upper border of the petrous temporal bone. Posteriorly, at the same horizontal level is a wide groove on the inner surface of the skull, which extends to the midline and is made by the transverse sinus. The two grooves meet at the internal occipital protuberance, which lies opposite the external occipital protuberance. Above the internal occipital protuberance (i.e. above the posterior fossa) is the groove made by the superior sagittal sinus. At the internal occipital protuberance the sagittal groove turns to one side (usually the right) into the transverse groove. The other transverse groove (usually the left) is narrower; it begins at the internal occipital protuberance by the inflow of the straight sinus. The tentorium cerebelli is attached to the margins of the transverse groove. Anteriorly, the transverse sinus is continuous with the sigmoid groove, which indents the cranial surface of the mastoid parts of the temporal bone (see Fig. 6.101, p. 441). Lower down, the sigmoid groove indents the occipital bone, which forms the inferior margin of the jugular foramen. The superior margin of the foramen is formed by the sharp inferior edge of the petrous part of the temporal bone, which is notched here by the inferior ganglion of the glossopharyngeal nerve (see Fig. 6.105, p. 446).

Anterior to the foramen magnum, the basiocciput, the posterior part of the sphenoid body and the dorsum sellae form a transversely concave sloping surface, the clivus. On each side the clivus is separated from the petrous temporal bone by a fissure in which the inferior petrosal sinus runs down to the jugular foramen. The basilar plexus of veins is lodged in the dura on the clivus and receives blood from the overlying pons and medulla. The plexus drains into the inferior petrosal sinuses.

Medial to the inferior margin of the jugular foramen is a rounded prominence, the jugular tubercle (see Fig. 6.105, p. 446). It lies above the occipital condyle, and between them the bone is perforated obliquely by the hypoglossal canal. The hypoglossal nerve enters here as two roots (see Fig. 6.109, p. 452). They are separated by a flange of dura mater that often ossifies. The glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory nerves lie on the surface of the jugular tubercle on their way to the jugular foramen. Above the jugular foramen is the internal acoustic meatus, through which pass the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves, nervus intermedius and labyrinthine vessels.

The internal occipital crest runs down in the midline from the internal occipital protuberance; to it is attached the falx cerebelli over the occipital sinus.

Mandible

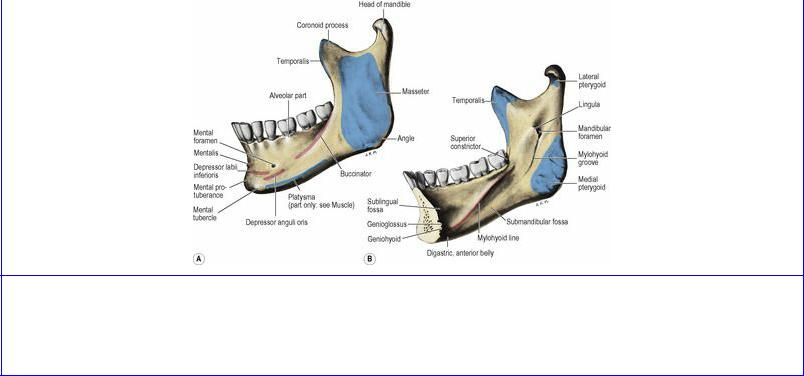

The mandible (Fig. 8.5) consists of a horizontal U-shaped body, which is continuous at its posterior ends with a pair of vertical rami.

Figure 8.5 A Left half of the mandible: lateral aspect. B Right half of the mandible: medial aspect. Genioglossus and geniohyoid are attached to the superior and inferior genial tubercles respectively.

The body of the mandible is projected up around the teeth as alveolar bone which forms the walls of the tooth sockets. The alveolar bone is covered by mucoperiosteum to form the inner and outer gums (gingivae). The cavity of the tooth socket gives attachment to the periodontal ligament; loss of this fibrous tissue in the dried skeleton commonly allows the teeth to rattle in the bone. Healthy teeth will not fall out of the dried mandible, for the alveolar bone is constricted somewhat about their necks. After the loss of a tooth, living alveolar bone atrophies and the bottom of the socket fills up with new bone; thus a glance at a gap will tell whether the tooth was lost before or after death.

On the outer surface of the body the sharp anterior border of the ramus extends forward as the external oblique line, to which the buccinator is attached opposite the molar teeth (Fig. 8.5A). The mental foramen lies halfway between the upper and lower borders of the body, in line with the interval between the two premolars. Its position varies with age (see p. 33). It faces backwards and slightly upwards in the adult, but directly laterally in early childhood; this influences the direction in which a needle is advanced for a mental nerve block. Depressor anguli oris is attached below the mental foramen and depressor labii inferioris anterior to the foramen, deep to the former muscle. Mentalis is attached near the midline. The lower border of the mandible gives attachment to the investing layer of deep cervical fascia, and to the platysma before some of its fibres pass on to the face. The lower border is crossed by the facial vessels and sometimes by the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve just in front of the masseter (see Fig. 6.11, p. 350).

The whole of the lateral surface of the ramus gives insertion to masseter. The posterior border of the ramus is projected up as the neck, which expands into the head (condyle) of the bone. The sharp anterior border continues up into the pointed coronoid process . The medial surface of the coronoid process, adjacent to its margins, is bevelled for the attachment of temporalis (Fig. 8.5B). The posterior border of this bevelled area is marked by a slight crest which runs downwards and forwards to the medial margin of the socket for the third molar tooth. The anteroinferior part of the temporalis tendon divides into two bands and the deep band is attached to this crest, which accordingly is referred to as the temporal crest. Between the lowest part of this crest and the posterior part of the oblique line is the small triangular retromolar fossa behind the last molar tooth.

The inner surface of the body is characterized by the mylohyoid line which forms a ridge that runs downwards and forwards from just below the posterior border of the third molar tooth (Fig. 8.5B). This fades anteriorly although the mylohyoid muscle attachment continues to the midline between the lower mental spine and the digastric fossa. The mental spines (previously called genial tubercles) are four small projections low down in the midline; genioglossus arises from the upper pair and geniohyoid from the lower pair of spines. The digastric fossae are two oval depressions on either side of the midline, on the inner aspect of the lower border of the mandible, for the attachment of the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles. Above the anterior part of the mylohyoid line is a smooth concavity, the sublingual fossa, which lodges the sublingual gland, and below the line the smooth submandibular fossa lodges the superficial part of the submandibular gland. Above the mylohyoid ridge the medial surface of the mandible is grooved below the last molar tooth; the lingual nerve lies here below the attachment of the pterygomandibular raphe just behind the last molar tooth (see Fig. 6.22A, p. 365).

The medial surface of the ramus is characterized by the lingula, a small tongue of bone at the anterior margin of the mandibular foramen, which lies halfway between the anterior and posterior borders of the ramus, level with the occlusal surfaces of the teeth (Fig. 8.5B). The inferior alveolar nerve and vessels pass through the foramen. The sphenomandibular ligament is attached to the lingula. The ligament is pierced by the mylohyoid vessels and nerve and these lie in the mylohyoid groove, a narrow sulcus that runs forwards from the mandibular foramen below the mylohyoid line. Between the mylohyoid groove and the angle of the mandible the medial pterygoid muscle is inserted, and irregular bony ridges lie in this area for attachment of the fibrous septa that characterize the muscle.

The neck of the mandible is hollowed anteriorly by the pterygoid fovea for the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Posteriorly the upper part of the neck is triangular and smooth. This area lies above the attachment of the temporomandibular joint capsule and is lined by synovial membrane. The lateral temporomandibular ligament is attached below this and to the lateral surface of the neck. The auriculotemporal nerve and the maxillary artery and vein cross the medial aspect of the neck, lying between it and the sphenomandibular ligament, together with parotid gland tissue.

The head of the mandible is markedly convex from front to back and slightly convex from side to side. The mediolateral axis is longer than the anteroposterior, and projects beyond the neck as medial and lateral poles, the former being more prominent. This axis is directed medially and slightly backwards. The head is bent slightly anteriorly on the neck, such that the articular surface faces upwards and forwards.

Ossification of the skull

Ossification of the skull occurs in both membrane and cartilage. The cranial vault develops in membrane, the skull base mainly in cartilage and the facial bones in membrane. Accordingly, the frontal and parietal bones develop in membrane. At birth the frontal bone is in two parts separated by the metopic suture. Fusion of this suture starts in the second year and is complete by 7 years. But the suture may persist in a small proportion of persons, in whom it must not be mistaken for a fracture line.

The squamous part of the occipital bone above the superior nuchal line ossifies intramembranously and the rest of the bone endochondrally. The skull base component of the occipital bone develops

from the sclerotomes of the four occipital somites (see p. 23), and a pair of parachordal cartilages on either side of the cranial end of the notochord. At birth the bone is in four parts: the squamous part, the median basiocciput and a pair of (lateral) exoccipital parts. The squamous and exoccipital parts fuse by the third year and by the sixth year the whole bone is one entity.

The body of the sphenoid bone develops from presphenoidal and postsphenoidal cartilages, the latter forming the sella turcica and dorsum sellae. Endochondral ossification in the adjacent ala orbitalis and ala temporalis give rise to the lesser wing and a part of the greater wing. The rest of the greater wing and the medial and lateral pterygoid plates ossify in membrane. At birth the sphenoid is in three parts: the greater wing being separate from a central part comprising the body and lesser wings. The three parts unite during the first year. At birth the body of the sphenoid is separated from the basiocciput by cartilage. This spheno-occipital synchondrosis (primary cartilaginous joint) begins to fuse between 12 and 14 years of age but ossification is not complete until 20 to 25 years of age, allowing for backward extension of the hard palate as more teeth erupt and providing space for the growing nasopharynx. Premature fusion between the sphenoid and occipital bones results in a depressed nasal bridge and a flat face.

The squamous and tympanic parts of the temporal bone ossify in membrane, while the petrous and styloid elements ossify in cartilage. The petrous part develops by ossification of the otic capsule that houses the vestibulo-cochlear apparatus. At birth the temporal bone is in three parts: the squamous and tympanic components have united but are separate from the petrous part and styloid process. All parts unite during the first year (see p. 33). A secondary ossification centre for the styloid fuses with the rest of the process after puberty.

The mandible, maxilla, vomer, inferior concha and the zygomatic, nasal, lacrimal and palatine bones ossify in membrane. The mandible is the second bone (after the clavicle) to start ossifying in the fetus; it does so in the sixth week by an ossification centre situated lateral to Meckel's cartilage (see p. 25). As intramembranous bone formation continues, this first branchial arch cartilage becomes incorporated in the developing mandible. Only the lingula and some occasional ossicles in the chin region of the mandible develop from Meckel's cartilage. A cone-shaped secondary condylar cartilage appears in the tenth week and, although it is largely replaced by bone before birth, growth continues here until 20 to 25 years of age.