- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

2 Terraced Vineyards in Europe: The Historical Persistence … |

19 |

2.6Convergent Legacies

The historical processes outlined above gave rise to a group of common legacies that controlled the history of terraced wine-growing areas in the course of the twentieth century. Those belong to the picture of general reduction in Europe of the use of terracing, indicated by slight chorological variations and varying intensity according to the region.

Such contraction occurred in connection with a general productivity crisis in farming on the slopes, coinciding both with mechanisation of agriculture on level ground and with emigration towards urban or industrial centres, or, for the Mediterranean coasts, to tourist centres. The contraction was brought about in real terms by the replacement of terracing with other forms of management through the possibilities offered by mechanisation, by expansion of residential areas and, above all, by abandonment of the land. This last phenomenon assumed almost everywhere astounding dimensions, with reductions that in Italy often exceeded 75% of land previously under cultivation. In Calabria’s Costa Viola, the extent of cultivated terracing has dropped from 612 ha in 1929 to 130 ha today (Nicolosi and Cambareri 2007); in the Cinque Terre, an area among the most hit by abandonment, the passage has been from a maximum of 1200 ha of cultivated land in the course of the twentieth century to around 100 ha today (Besio 2002). This trend of contraction also continues in our times, if more slowly, in spite of various operations of support for marketing and of heritage conservation, among them the inclusion of various areas in UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites. In Lavaux, the loss between 1993 and 2015 was 40 ha (OCVP 2015). Between 2006 and 2015, the wine-growing area of the Vallese, terraced and not (but the former was probably worst hit), decreased by an annual rate of between 4 and 8% (Canton du Valais 2016).

As has been said, elsewhere the dominant phenomenon has by contrast been the movement towards other ways of managing the slopes. In Alto Douro, terracing has been replaced by what is known as patamares and by vertical planting. The latter is also responsible for the major transformation of the wine-growing landscape in the Rhine and Moselle valleys.

To the reasons for the decline in terracing cited above must be added that of the significant diseases that attacked the vine in Europe from the mid-nineteenth century. Oidium, peronospora and above all phylloxera, while not permanently changing the productive assets on a national scale (Bonardi 2014; Jacquet and Bourgeon 2010), sometimes began or hastened the process of abandonment at a local or regional level.

As appears in the course of specific research studies (APARE 1983; Bonardi and Varotto 2016), one of the causes of these areas’ economic weakness is the fragmentation of ownership. Among the most macroscopic examples can be cited the distribution values of ownership in Val d’Aosta, where 80% of the total cultivated land (equivalent to 98% of the businesses) is held in properties of less than one hectare, and those of Ribeira Sacra, with 93% of the cultivated land subdivided

20 |

L. Bonardi |

between farms of less than two hectares (www.cervim.org). The latter situation is very similar to that of Calabria’s Costa Viola, where the average size of the holdings is less than two and a half hectares (Di Fazio et al. 2005).

This phenomenon has its origins, as has been seen, in the processes of the actual construction of these holdings and, specifically, from those aspects of management of the ownership, common to so many areas, that from the beginning of the slopes’ agricultural exploitation has favoured strong parcellisation of the land ownership. Overcoming the problematic legacy through systems of consolidation represents a major challenge for these areas today.

Notwithstanding these findings, the reduction of terraced wine-growing areas, as with those olive-growing, has in general been less drastic in comparison to other crops, including cereal and fruit growing, once very widespread.

It is clear that the ubiquitous establishment of a market economy has in the first-place penalised subsistence farming and, more generally, mixed cropping systems. By contrast, highly specialised productive systems, as exactly is terraced viticulture, open to the international markets, found themselves in the twentieth century in a relatively advantageous position. The centuries of inclusion in commercial circuits, guaranteed by their position along favourable communication routes or alongside market outlets, placed these areas very early on in a competitive system on a continental, and in some cases world, scale. In such a context were developed both forms of protection and improvement of the quality of production and pronounced specialisation. Among the last are the sweet or aromatic wines that mark the areas of Alto Douro (Porto), Banyuls (Vin doux naturel), Pantelleria (Moscato di Pantelleria and Passito di Pantelleria) and the Cinque Terre (Sciacchetrà).

Specialisation and quality perfecting in the course of the twentieth century have built an advantage that benefits the best wine estates of these economies, even if built on terracing, compared to others. From this perspective, it does not seem a matter of chance that the area of the largest single terraced viticulture in Europe corresponds to the world’s first viticulture designation, known as the “Pombaline Demarcations”, instituted from 1756 to control the quality of the wines of Alto Douro8 (Bianchi de Aguiar 2010). The first territorial delimitation of a sweet wine, on the other hand, dates back to 1909, that of the terraced area of Banyuls (Ferrer 1930).

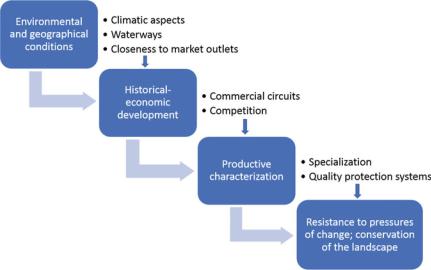

From the same perspective of protection of the quality, and brand, of wine production is probably to be understood the system of vintage announcements applied for centuries in Valtellina following a rare model, for capillarity and historical persistency, in Italian viticulture. The explanatory layout of the process that leads from the geographical–environmental determinant to the survival of today’s terraced viticulture is summarised in Fig. 2.4.

8The systems of demarcation instituted in the first half of the eighteenth century in Chianti and Tokaj were of different origins.

2 Terraced Vineyards in Europe: The Historical Persistence … |

21 |

Fig. 2.4 Geographic variables and historical–economic development of terraced viticulture

2.7Conclusions

This work has highlighted the historical and geographical reasons, convergent and interconnected, that governed the localisation and evolution of the principal terraced wine-growing areas. These are part of the wider picture of the relationships between the sites of European viticulture with the centres of wine consumption. The problems linked to the transport of the wine over long distances, connected with those of its preservation, were addressed historically by a topographical approach with the solution of placing the vineyards along waterways, from time to time represented by rivers, lakes, the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. By guaranteeing the best means of transport for a product peculiarly liable to deterioration, such routes determined the economic fortune, often long-lasting, of the wine-growing regions developed along them. For Alpine localisation, an analogous solution was to some extent guaranteed by the existence of climatically favourable areas and the position alongside market outlets to Central Europe.

Much of the extent of European terraced vineyards can be explained by one or the other condition, which gave rise to the early opening up of the economies of these regions.

In fact, as Unwin (2005: 144) has already pointed out for the mediaeval period, “the idea of an independent Mediterranean peasantry, producing its own subsistence needs on its own land, is largely a myth”. This concept is certainly applicable to the large terraced areas, even if in a number of cases only from the modern age, and weakens the traditional vision of terracing as a holding and representation of

22 |

L. Bonardi |

self-sufficiency. In all probability, the economic dimension of these regions, strongly specialised from an early date, and the search for qualitative solutions, later brought about the positive major resistance in the face of the crises that struck European terraced viticulture in the course of the last century.

References

Agnoletti M, Emanueli F, Maggiari G, Preti F (2012) Il disastro ambientale del 25 ottobre 2011 nelle Cinque terre. In: Agnoletti M, Carandini A, Santagata W (eds) Florens 2012—Studi e ricerche. Essays and researches, pp 25–39. Bandecchi e Vivaldi

Aldighieri B, Bonardi L, Comolli R, Conforto A, Mariani L, Mazzoleni G, Rizzotti T (2006) Vine-growing in Valchiavenna (SO): the Pianazzola project. Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana 6:17–27 Special issue

APARE (1983) Des Agriculteurs en terrasses. Analyse, synthèse. Avignon: A.R.E.E.A.R. Languedoc Roussilon—Ministère de l’Agriculture

ASR Lombardia (Annuario Statistico Regionale) (2015) http://www.asr-lombardia.it/ASR/ lombardia-e-province/agricoltura/produzione-agricola-zootecnia-e-risultati-economici/tavole/ 9853/2015/. Accessed 20 Feb 2017

Barbera G, Cullotta S, Rossi-Doria I, Ruhl J, Rossi-Doria B (2009) I paesaggi a terrazze in Sicilia. Metodologie per l’analisi, la tutela e la valorizzazione. ARPA, Sicilia

Bartaletti F (2006) Pendii terrazzati nelle Alpi Cozie: i casi di Chiomonte e Bardonecchia. Geotema: Paesaggi terrazzati 29:25–34

Besio M (2002) The conservation of built landscape and the maintenance of a collective architecture. In: World heritage expert meeting on vineyard cultural landscapes, Tokaj, Hungary, 11–14 July 2001, pp 41–42. Secretariat of the Hungarian World Heritage Committee in collaboration with the UNESCO World Heritage Centre

Bianchi de Aguiar F (2010) La spécificité des paysages du Douro. In: Pérard J, Perrot M (eds) Paysages et patrimoines viticoles. Rencontres du Clos-Vougeot 2009. Centre Georges Chevrier, pp 91–97

Blanc J-F (2001) Terrasses d’Ardèche. Paysages et Patrimoine. chez l’auteur

Blanchemanche Ph (1990) Bâtisseurs de paysages. Editions de la Maison de Sciences de l’Homme Bonardi L (2010) Les paysages viticole en terrasses: des espaces de convergence. In: Pérard J, Perrot M (eds) Paysages et patrimoines viticoles. Rencontres du Clos-Vougeot 2009. Centre

Georges Chevrier, pp 129–140

Bonardi L (2014) Paesaggi e peculiarità dei terrazzamenti viticoli. In: Bonardi L, Caligari A, Foppoli D, Gadola L, Grossi D, Stangoni T, Vanoi G (eds) Paesaggi valtellinesi: trasformazione del territorio, cultura e identità locale. Mimesis, pp 71–82

Bonardi L, Cavallo F (2014) Résistence et renaissance de la viticulture dans la lagune de Venise. In: Pérard J, Perrot M (eds) Le vin en heritage, anciens vignobles, nouveaux vignobles. Rencontres du Clos-Vougeot 2014. Centre Georges Chevrier, pp 85–107

Bonardi L, Varotto M (2016) Paesaggi terrazzati d’Italia. Eredità storiche e nuove prospettive. Angeli

Camera C, Apuani T, Masetti M (2015) Modeling the stability of terraced slopes: an approach from Valtellina (Northern Italy). Environ Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4089-0 Canton du Valais (2016) Année vitivinicole 2015—Rapport annuel. Département de l’économie,

de l’énergie et du territoire, Office cantonal de la viticulture. https://www.vs.ch/documents/ 180911/1045634/Ann%C3%A9e+vitivinicole+2015.pdf/331daa33-a42e-4e26-a7d4-98bf4cc02 296. Accessed 12 Dec 2017

2 Terraced Vineyards in Europe: The Historical Persistence … |

23 |

Carmona J, Simpson J (1998) A vueltas con la cuestión agraria catalana: el contrato de “Rabassa morta” y los cambios en la viticultura, 1890–1929. In: Documento de Trabajo 98-07 Depto. de Hist. Económica e Instituciones Serie de Hist. Económica e Instituciones 01. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

Ceschi R (1999) Nel labirinto delle valli. Uomini e terre di una regione alpina: la Svizzera italiana. Casagrande

Cevasco A, Pepe G, Brandolini P (2014) The influences of geological and land use settings on shallow landslides triggered by an intense rainfall event in a coastal terraced environment. Bull Eng Geol Env 73:859–875

Chemin A, Varotto M (2008) Le “masiere” del Canale di Brenta. In: Scaramelllini G, Varotto M (eds) Paesaggi terrazzati dell’arco alpino. Atlante. Marsilio, pp 97–101

Consell de Mallorca (2007) Actes de les jornades sobre terrasses i prevenció de riscs naturals. Actas de las jornadas sobre terrazas y prevención de riesgos naturales, Mallorca, 14, 15 i 16 de setembre de 2006. Departament de Medi Ambient, Consell de Mallorca, Palma de Mallorca Constans M (2010) Le patrimoine paysager viticole de Banyuls, entre reconstruction et destruction. In: Pérard J, Perrot M (eds) Paysages et patrimoines viticoles. Rencontres du

Clos-Vougeot 2009. Centre Georges Chevrier, pp 181–199

Courtot R (1990) La place des terrasses dans les systèmes agricoles méditerranéens. In: Provansal M (ed) Méditerranée 71. L’agriculture en terrasses sur les versants méditerranéens; histoire, conséquences sur l’évolution du milieu, p 42

d’Abreu C (2007) Navegação no rio Douro: o sonho (re)corrente de Castela. Douro 22:37–78 de Beauchamp Ph (1992) L’architecture rurale des Alpes-Maritimes. Édisud

de Montaigne M (1889) Journal du voyage de Michel de Montaigne en Italie, par la Suisse et l’Allemagne en 1580 et 1581. Lapi

Del Treppo M, Leone A (1977) Amalfi medievale. Giannini

Di Fazio S, Malaspina D, Modica G (2005) La gestione territoriale dei paesaggi agrari terrazzati tra conservazione e sviluppo. AIIA

Dion R (1959) Histoire de la vigne et du vin en France des origines au XIX siècle. Doullens Ferrer G (1930) Le vignoble de Banyuls-sur-Mer. Revue géographique des Pyrénées et du

Sud-Ouest 2:185–192

Ferrigni F (2011) Dal Ducato alla Costiera Amalfitana. In: Ferrigni F (ed) Le regole del vernacolo. Viaggio nel patrimonio edilizio minore della Costiera Amalfitana e dell’Irpinia. www.univeur. org. Accessed 15 May 2017

Formica C (2010) Paesaggi terrazzati tra storia e sostenibilità. Il litorale campano e l’isola d’Ischia. Studi e ricerche socio-territoriali 0:25–56

Frapa P (1984) Le terrasses de culture entre le passé et l’avenir. Forêt méditerranéenne 2:129–130 Frapa P (1997) Restanques, faïsses ou banquettes: l’homme, l’eau et la pente. Études

vauclusiennes 58:59–66

Gadille R (1978) L’héritage d’une viticulture antique, vignes et vins de Côte-Rôtie et Condrieu. Revue de Géographie de Lyon 53:7–22. https://doi.org/10.3406/geoca.1978.1213

Gauchet S (2001) Des pratiques agricoles aux pratiques paysagères. Aménagement et Nature 141:55–66

Gauvard C (1996) La France au moyen âge: du Ve au XVe siècle. PUF

Gugerell K (2009) Wine-Growing in the Wachau—red and white resistance. In: Splechtna B (ed) Proceedings of the international symposium: preservation of biocultural diversity—a global issue, BOKU University, Vienna, 6–8 May 2008, pp 107–113. University of Natural Resource Management and Applied Life Sciences, Wien

Iona ML (1986) La città di Maria Teresa. Pragmatismo e pianificazione. UR: urbanismo revista 4:21–25

Jacquet O, Bourgeon J-M (2010) Crise du phylloxéra et mutations du paysage. In: Pérard J, Perrot M (eds) Paysages et patrimoines viticoles. Rencontres du Clos-Vougeot 2009. Centre Georges Chevrier, pp 151–162

Kieninger PR, Gugerell K, Penker M (2016) Governance-mix for resilient socio-ecological production landscapes in Austria—an example of the terraced riverine landscape Wachau. In:

24 |

L. Bonardi |

UNU-IAS, IGES (eds) Mainstreaming concepts and approaches of socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes into policy and decision-making (Satoyama initiative thematic review vol 2). United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability, Tokyo, pp 36–49

Lorusso D (forthcoming). Fa vini potentissimi e assai. Geografia e storia della viticoltura in Valtellina. In: Panzera F (ed) Viti&Vini. La vite e il vino nella nostra cultura, con uno sguardo a Ticino, Vallese e Valtellina. Bollettino Storico della Svizzera Italiana, 14, Edizioni Salvioni

Lourenço-Gomes L, Pinto L, Rebelo J (2015) Wine and cultural heritage. The experience of the Alto Douro Wine Region. Wine Econ Policy 4:78–87

Moreno D (2012) Valle d’Aosta. In: Agnoletti M (ed) Environmental history, vol 1. Italian historical rural landscapes. Spriger. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5354-9_6167-173

Moschini C (2017) La vite in Val d’Ossola. Una coltivazione dal grande passato. Silvana Nicolosi A, Cambareri D (2007) Il paesaggio terrazzato della Costa Viola. In: Atti XXXVI

Incontro di Studio Ce.S.E.T. Firenze University Press, pp 179–194

OCVP—Office Cantonal de la Viticulture et de la Promotion (2015) Registre Cantonal des Vignes 2015. Department de l’economie et du sport—Service de l’agriculture, Canton de Vaud. http:// www.vd.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/themes/economie_emploi/viticulture/fichiers_pdf/15_12_ 16_RCV_2015.pdf. Accessed 30 Oct 2016

Parvex F, Turiel A (2001) Ameliorations des structures agricoles et paysageres dans les perimetres viticoles. Sauvegarde des murs en pierres seches et du vignoble en terrasses valaisan. Etude exploratoire, rapport final. Service de l’agriculture de l’etat du valais, Offices des améliorations foncières et de la viticulture. http://www.pierreseche.com/a_lire/rapport_final_SEREC.pdf. Accessed 01 Sept 2016

Pereira GM, Morais Barros A (2016) Port Wine and the Douro region in the early modern period. RIVAR 3:127–144

Petit C, Werner K, Höchtl F (2012) Historic terraced vineyards: impressive witnesses of vernacular architecture. Landsc Hist 33:5–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01433768.2012.671029

Pini AI (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: Archetti G (ed) La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Centro Culturale Artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, pp 585–598

Provansal M (ed) (1990) L’agriculture en terrasses sur les versants méditerranéens; histoire, conséquences sur l’évolution du milieu, Séminaire Aix-en-Provence, 3 février 1990. Méditerranée 71

Quaini M (1973) Per la storia del paesaggio agrario in Liguria. Atti della Società ligure di storia patria 86:201–360

Queijeiro J, Vilanova M, Rodriguez I, de la Montaña J (2010) Paysages viticoles et terroir dans l’OAC Ribeira Sacra (Galice, NO de l’Espagne). In: VIII international terroir congress, chap 6, pp 91–96. http://terroir2010.entecra.it/atti/VIIICongress_sess6.html. Accessed 01 Sept 2016

Romegialli G (1834) Storia della Valtellina e delle già Contee di Bormio e Chiavenna, vol 1. Cagnoletta

Scaramellini G (2014) Coltura della vite, produzione e commercio del vino in Valtellina (secoli IX-XVIII). Territoires du vin 6. http://revuesshs.u-bourgogne.fr/territoiresduvin/document. php?id=1765

Scaramellini G, Varotto M (eds) (2008) Paesaggi terrazzati dell’arco alpino. Atlante. Marsilio Schultz HR (2010) Paysages et vignobles des vallées du Rhin et de la Moselle. In: Pérard J,

Perrot M (eds) Paysages et patrimoines viticoles. Rencontres du Clos-Vougeot 2009. Centre Georges Chevrier, pp 141–150

Tarolli P, Preti F, Romano N (2014) Terraced landscapes: from an old best practice to a potential hazard for soil degradation due to land abandonment. Anthropocene 6:10–25. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ancene.2014.03.002

Terranova R (1989) Il paesaggio costiero terrazzato delle Cinque Terre in Liguria. Studi e Ricerche di Geografia 12:1–58

Terranova R, Bernini M, Zanzucchi F (2006) Geologia, geomorfologia e vini del Parco Nazionale delle Cinque Terre (Liguria, Italia). Boll Della Soc Geol Ital 6:115–128

2 Terraced Vineyards in Europe: The Historical Persistence … |

25 |

Unwin T (2005) Wine and the vine. An historical geography of viticulture and the wine trade. Routledge

Varanini GM (2003) Le strade del vino. Note sul commercio vinicolo nel tardo Medioevo (con particolare riferimento all’Italia settentrionale). In: Archetti G (ed) La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Centro Culturale Artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, pp 635–663

Vinea Wachau (2014) Wachau souterrain—geology and wine. http://www.vinea-wachau.at/en/ vinea-wachau/geology-and-wine/. Accessed 15 Jan 2017

www.cervim.org. Accessed 10 June 2016

Chapter 3

Italian Terraced Landscapes:

The Shapes and the Trends

Mauro Varotto, Francesco Ferrarese

and Salvatore Eugenio Pappalardo

Abstract Since the 1980s, Italian terraced landscapes have become the object of scientific attention, with a significant increase in systematic studies only in the last twenty years. However, the state of knowledge is still fragmentary. The studies were initially concentrated in limited areas considered particularly significant from an environmental or historical point of view. Even today, a detailed, national map of terraced landscapes is still lacking. Starting from this “state of the art” formed by extremely differentiated knowledge levels, the project “Mapping Terraced Landscapes in Italy” (MAPTER) began, thanks to the collaboration of several research centers at the third Meeting of the International Terraced Landscapes Alliance (ITLA) (October 6–15, 2016). MAPTER collected and attempted to harmonize, for the first time, the available data on both local and regional scales, integrating them with further surveys for uncovered areas, to produce an initial estimate of national terraced systems. This contribution delineates, first, the project’s outcomes, presenting the initial data concerning the extent and geographical distribution of Italian terraced systems. The second part of the contribution includes observations on the new processes of returning to abandoned terraced lands. These observations have emerged from a survey (the Livingstones Project) promoted by the Italian Alpine Club, and they are used here to identify practices of a virtuous “third way” for managing rural mountain areas, far from marginality, abandonment, and productive intensification.

M. Varotto (&) F. Ferrarese S. E. Pappalardo

Department of Historical and Geographic Sciences and the Ancient World, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

e-mail: mauro.varotto@unipd.it

F. Ferrarese

e-mail: francesco.ferrarese@unipd.it

S. E. Pappalardo

e-mail: salvatore.pappalardo@unipd.it

© Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 |

27 |

M. Varotto et al. (eds.), World Terraced Landscapes: History, Environment, Quality of Life, Environmental History 9, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96815-5_3