- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory |

243 |

de la Soudière 2010). Precise in its location, defined in its temporality (the “place” can also be the convenient moment), and—for these reasons—having a name, the place is often personified as concealing a “spirit” or a “genius” (genius loci); the spirit of a “place” is not attached to a “space,” which has flexible outlines and a moldable morphology. Places (or topoi) are thus assimilated to beings and are our “social body”: an extension of ourselves in the environment (Leroi-Gourhan 1943). This beautiful metaphor reminds us of the ceaseless comings and goings between reality and per- ception—the perpetual interaction between the physical territory and its felt, historic, social, and patrimonial contexts. This complex process ends by developing local cultures, which are made and unmade in groups and periods. Each of these stages or concrete moments corresponds to a time/space, combining the objective space with the material, ideal, and sensory elements of each instant into a concretude (Chouquer 2001). All these instants are different and succeed each other with the complicity of the land users.

15.3Country Planning: Lifestyles

Implementing terraced lands mobilizes the concepts and mechanisms we have described above. Terracing participates in global country planning, prioritizing rural lands and, most of all, those having an agro-sylvo-pastoral production. Their spread can be considerable, and though other operations are necessary for their creation, the most visible technique used is dry-stone walling. This technique absorbs a large part of the materials excavated from freshly turned soils and supports the drainage and aeration of terraced plots. It maintains the place’s unity and coherence because it is largely manual and craft (few operators, no special tools, empirical apprenticeship despite theoretical books that have circulated since the nineteenth century and are multiplied today). The material (the stone) and the technique (building with no mortar) call up to performance, and this factor encourages the use of terraces and dry-stone construction. Additionally, dry-stone walling, just as land terracing, shows—beyond knowledge, skill, and ingenuity—the sensibility of the body and of the spirit via adaptation to contexts and milieus.

Finally, expressed by drawings and artifacts largely executed in dry stone, the “writing” of terraces arranges and orders space by showing usage rules (cultures, irrigation, storages, passages, etc.) and by inciting relevant behaviors (cyclic presence/absence of users, joint arrangements and help for productions, development of leisure activities and user-friendliness, etc.). These functions strengthen every link: inter-spatial (matching land location to the plans of traffic, etc.); inter-seasonal (matching cultures, wood cuts, animals’ passes, hunting calendars, etc.); intergenerational (transmission of land ownership, uses, features of the soil, water circulation, climate, etc.); and inter-community (drainages, road networks, trade, fairs and other festivities, etc.). There is a whole set of relationships concerning family, neighborhood, production, and cooperation that structures societies, property, and technical systems.

244 |

A. Acovitsióti-Hameau |

Similarly, if this “putting in writing” brings order, it also draws attention to activities and behaviors and thereby perpetuates them. Signaling arrangements (wall crowning, cairns, marks), hunting devices (seats, recesses, low walls), and pastoral markers (signals forbidding or allowing entry in pasture land, signals for huts and water supplies) bear indications for possible actions, misadvised or authorized, and instructions of good behavior for habitual or occasional users and for passers-by. All of them should recognize these signals or—at least—note them and leave them in place.

Efficiency and aesthetics create another register of shared perceptions, giving immaterial qualities to landscape patterns, constructed works, and modes of building—conferring an identity recorded by collective memoirs. For instance, people of Banyuls keep cultivating their vineyard in the “old way” (Fig. 15.3) and promote their products by exalting the configuration of the relief carrying the plants: steep the slope, strong the wine!

Feelings of neatness and strength from terraced spaces are emphasized as the view embraces big areas without caring about details. These panoramic views increase the “misleading clarity that confer the height and a faraway vision” (Urbain 2010). Examined near the ground or on a small scale, the same arrangements give a different image. It is because the vertiginous masks the profusion of the structures on the ground. These structures often have a modest appearance and visibility, but their existence is essential for the arrangement, the stability, and the functioning of the terraced lands’ implementation. Most of the devices for road networks, water

Fig. 15.3 Steep terraced slopes of the Banyuls—Collioures vineyard, Roussillon, France (Photo ASER Association)

15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory |

245 |

Fig. 15.4 Terraced high mountain around Arés, Maestrat, Spain (Photo ASER Association)

streaming, storage, and rest are in this class. Even important constructions, such as huts for laborers, are not always recognizable in the overviews, which display “staged” spaces, the shown images being conditioned to impress (Fig. 15.4). Walking through these spaces allows people to discover their “secrets.” These are often revealed to be treasures of ingenuity, demonstrating that places, functions, and building techniques fuse to one another and are attached to social points and imaginary items to create personalized spatial unities.

15.4What Is Important? The System

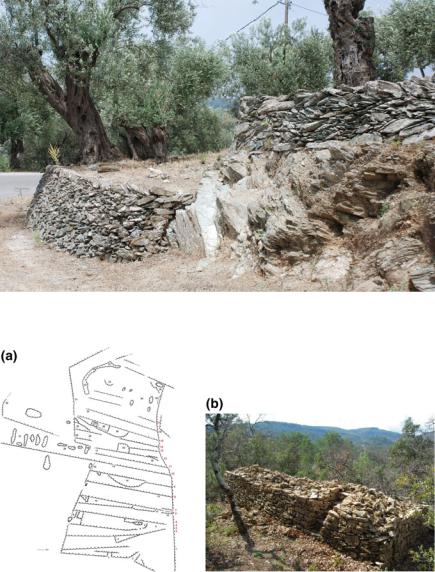

Carefully examining terraced lands and dry-stone settings shows their complexity and diversity. The smallest details reveal lifestyles and bear witness to the builders’ intelligence. Global country planning presupposes many operations and realizations, all essential and complementary: the breaking-up and drainage of lands; the shaping of plots; water courses and distribution; the partition and demarcation of cultivated, free, and wooded land; the implementation of roads and paths; the construction of utilitarian premises for peasants and foresters; and the establishment of pastoral parks and buildings. Access ramps and flying staircases through terraces, specific places for fruit trees such as olive trees (Fig. 15.5), a sun-bathed wall in front of which the dessert grapes mature, a “niche” to keep provisions cool or a hollow in the wall to tidy up tools, ropes, and flocks’ bells are all elements indispensable for the system.

246 |

A. Acovitsióti-Hameau |

Fig. 15.5 Olive trees’ protections in Lesvos, Greece (Photo ASER Association)

Fig. 15.6 Detailed country planning of a modest slope, Var, Provence, France (Photo ASER Association)

The planning affecting a hillside in the Var department’s hinterland (Provence, France) shows the complicity and complementarity between the voluminous and the restricted, the mass and the detail. The set consists of terraces, stone heaps, and enclosure walls, and it covers the whole slope and the little plateau forming its summit (Fig. 15.6).

15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory |

247 |

It is bare, thankless land, where stone appears everywhere and where one wonders if culture, even minor, is possible. However, the little, local farming community made this area fruitful, cultivating it annually and driving flocks to pasture, without neglecting the leisurely but also food-supplying activities of hunting and gathering. Functional since at least the middle of the nineteenth century, the area was gradually abandoned after World War II. Modest hunting and the grazing of small family herds subsisted until the early 2000s. Some years ago, the area became public, and the municipality intends to preserve all land accommodations, even if there is no precise plan of action yet.

Preliminary studies (topographies, ethnographical surveys, and archival research) are now finished, and the district periodically accepts guided visits, which discuss dry-stone walling and the lives of former rural people, whose hard labor is illustrated by built devices. Hunters and gatherers continue crossing the hillside. Despite the banality of the constructions (or, perhaps, because of it), the feeling of owning an exceptional patrimonial place makes its way among the state’s and inhabitants’ representatives. The concept of “lands of stone” and of “food giving stones” (Godefroid 2014) insinuates itself in the community’s agricultural and forest heritage. If the researchers and the authorities have a real responsibility for this evolution, this insinuation would not be possible without the sense (the spirit maybe?) of the place itself, which, apparently, awakens recollections of lifestyles practiced by well-known and intimate ancestors. Because memory can take hold of this sense, the place becomes part of the cultural heritage in a credible and practicable way.

The case presented above is generalizable for most of the terraced territories that are being recovered. For instance, recovering cultivation in several terraced areas of Majorca (Baleares, Spain) is intended to support alternative tourism touching the hinterland and the autumn/winter season and absorbing traditional agro-pastoral products, which are transformed and packaged in an innovative way (proposed forms and quantities, packaging types, various lots for tasting, etc.). This initiative also maintains farmers on these lands who, without such measures, would have abandoned them. So, numerous vernacular arrangements on the hillsides are rebuilt and reused, either because they welcome and supply circuits of agritourism or because the desire to develop internal wealth allows (and values) maintaining or returning to rural life. In Italy, “recoveries” or “stubborn forms of return” to rural life on terraced lands seem to have success, not due to the “fétichisation” of chosen places, but from their rehabilitating manners of living and reports to the environment that the society understands and adopts (Varotto 2008). In all contexts where innovations remain attentive to their heritages and are moderately achieved, social (new populations) and economic (new productions) transformations that accompany them do not upset the traditional vocations of places (dominant activities suitable to each land unit) or all people/territories (networks of traffic, mutual aid, and exchanges). These conditions are indispensable for the survival of terraced territories; the high level of symbiosis between inhabitants/users and time/spaces defines, not only the quality, but also the proper essence of their being. For this reason, “putting in place” and “putting in memory” terraced lands are processes