- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

50 |

L. Ažman Momirski |

and special factors of land-use changes related to terraces are typical of the Mediterranean world in general, including the Slovenian sub-Mediterranean area (Ažman Momirski and Gabrovec 2014). A volume on terraced landscapes at the regional scale of sub-Mediterranean Slovenia (Ažman Momirski 2014) contains a survey of historical sources of terraces, geological data, physiognomy of the terrain and terraced landscapes, and use/functions of terraces in various areas at the level of region, municipality, cadastral municipality, settlement, and plot. In some cases, preventing landslides on slopes is not necessary because terraces and their slopes have preserved the same form for almost two hundred years. However, planning and constructing new terraces demand a contemporary methodological approach (Ažman Momirski 2015b). In the Mediterranean landscape, terraces are a traditional element, whereas in the Pannonian landscapes, terraces are modern phenomena, created mostly in the 1960s and 1970s to facilitate intensive mechanized farming (Ažman Momirski and Kladnik 2015a). After reviewing documents at the national level (laws and strategies) and local level (spatial documents) to determine whether and how they refer to terraced landscapes, it is possible to propose a procedure to allow institutions at the national and local levels to map and evaluate terraced landscapes (Ažman Momirski and Berčič 2016). Nowadays, Lidar data offer an unprecedented accurate new interpretation tool for detecting terraced landscapes. The most significant feature of this new method is its reliability for detecting the exact boundaries of terraced areas (Berčič 2016). This new methodology will probably challenge the findings of previous studies presenting the diversity of Slovenian terraced landscapes (Kladnik et al. 2016a, b). The same authors contributed to a publication for the general public presenting terraced landscapes of the world and Slovenia (Kladnik et al. 2016a, b). Recently, Likar (2017) called attention to the fact that terracing was not only carried out on slopes to prevent erosion and mitigate the effects of droughts and flooding on farmland, but was also used in excavations for house foundations in settlements, for example, in northern Istria.

4.3State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

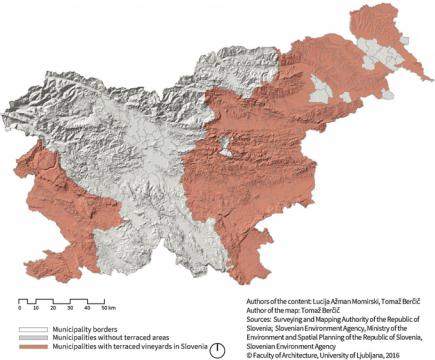

Reviewing all Slovenian territory, only 19 municipalities (out of 211) have no terraced landscapes, which altogether represent 3.3% of the country’s entire territory. In other words, terraced areas that form part of the cultural landscapes in Slovenia can be found in more than 90% of the country’s municipalities, corresponding to a little less than 97% of Slovenian territory. The presence of terraced landscapes in the municipalities is not uniform: In some municipalities, where most of the territory is flat, there may be only a few terraces on slopes that are not very steep at the edge of the municipality’s territory (borderline cases were included in the category of municipalities with terraced landscapes). In other municipalities, terraced landscapes may be the dominant landscape feature. Both active (i.e., cultivated) and abandoned terraces were considered in the review (Ažman Momirski and Berčič 2016).

4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes |

51 |

Various types of terraces exist within Slovenia’s terraced landscapes, but they are all made up of two basic formal elements: a terraced platform (or tread) and a terraced slope (or riser; Ažman Momirski 2008a, b, c, d). The criteria for determining the types of terraced landscapes are defined according to:

–The use or function of the terrace slope and terrace platform;

–The form of the terrace slope and terrace platform; and

–The construction of the terrace slope.

Land use relates to the exploitation of land through human activity in the landscape, and it is one of the best indicators of landscape structure and processes. Within Slovenia’s cultural landscapes, three main types of terraces can be distinguished based on land use (Ažman Momirski and Kladnik 2008, 2009):

–Agricultural terraces;

–Viticultural terraces; and

–Fruit-growing terraces.

Mixed types of terraces can be also found. Vegetables are grown below olive groves on terraces, fruit trees are planted on the slopes of agricultural terraces, and so on.

Agricultural terraces can be found all over Slovenia, in all of its major regions. Agricultural terraces are mostly meadows and pastures, and sometimes they are cultivated more intensively with crops or vegetables. Agricultural terraces in Slovenia differ extensively in their forms: Terraces in the high mountains just below the ridges mainly have wide terrace platforms with a steep gradient, an irregular plan, and extremely low terrace slopes; however, because of the high terrain inclination, these terraces are extremely high. In contrast, terraces at the foot of the hills, which are often low, have medium-wide terrace platforms and an almost equal proportion between terrace slopes and terrace platforms. There are also uniform, regular, higher terraces with only a few centimeters of the gradient of the terrace slope, and therefore again an identical proportion between the terrace slope and terrace platform (Ažman Momirski and Berčič 2016).

In many Slovenian landscapes, the development of cultural landscapes is inseparably linked to the development of viticulture. In the Middle Ages, farmers started to cultivate unworked land, and in the Gorizia region, for example, they planted vines on flat fields. After 1574, this type of grape cultivation was sometimes banned because it began to threaten cereal production. Prohibitions on planting grapes in fields and pastures, and a general prohibition on planting vineyards, appeared until the eighteenth century. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, the development of viticulture has been significantly affected by pests and diseases, such as gray mold of grape, peronospora, and grape phylloxera. Because phylloxera destroyed many vineyards, they had to be reconstructed, which prompted the renewed progress of viticulture. The farmers dug deep into vineyards, planting vines in rows and at proper distances. The new arrangement also improved the production options. During the First and Second World Wars, many vineyards were

52 |

L. Ažman Momirski |

destroyed and farmers started to abandon old vineyards and vineyards in less favorable areas because of labor shortages (Ažman Momirski 2008b).

Due to the specific features of production and favorable conditions for cultivating grapes, most vineyards in Slovenia are located on steep terrain, and one-fifth are terrace plantations (21%), among which 71% are arranged on slopes with a gradient over 9.1° (16%). Approximately, half of the vineyards on terraces can be found in the gradient class of 9.1°–17.0° (16–30%), and just under one-third are on slopes from 17.2° to 26.6° (31–50%). In 2015, 959 vineyards (229 ha) were planted on terraces with inclinations of 24.4°–31° (45–60%) and 101 vineyards (9 ha) on terraces with inclinations over 31° (60%) (Vineyard Census 2015). Viticulture on vineyard sites at elevations over 500 m, on slopes greater than 17.0° (30%), on terraces or embankments, and on small islands under difficult growing conditions is classified as “heroic viticulture.” This is a marginal form of viticulture, which is widespread in less than a tenth of wine-growing areas in Europe, and for which the criteria have been defined by CERVIM (2017). Since 1987, the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) has paid special attention to it.

It is also important to emphasize that an average winegrower in Slovenia cultivates only a small area, about half a hectare of vineyard. In 2015, over 90% of winegrowers were cultivating less than one hectare of vineyard, and the average vineyard size was 0.3 ha. For comparison, an average winegrower was cultivating a much smaller area (0.1 ha less) than in 2009 (Vineyard Census 2015). The study further showed that 104 municipalities in Slovenia have terraced vineyards (Fig. 4.1).

The wine-growing area of Slovenia is divided into three wine-growing regions (the Drava Region, which includes the Drava Valley in the northeast; the Lower Sava Region, which includes the Lower Sava Valley, White Carniola, and Lower Carniola in the southeast; and the Littoral Region, covering the traditional region of the Littoral in the southwest) and nine wine districts (Prekmurje, Styria, Bizeljsko-Sremič, Lower Carniola, White Carniola, the Gorizia Hills, the Vipava Valley, the Karst Plateau, and Slovenian Istria) as a consequence of the great variety of the landscape, different climate and soil conditions, and different natural conditions (Pravilnik 2003).

According to data from orthophotograph maps, there is almost 19,300 ha of vineyards in Slovenia, although the Register of Grape and Wine Producers (RPGV) lists only about 16,000 ha (Vinogradništvo in vinarstvo 2016). Data show that vineyards are increasingly shrinking at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Based on data from orthophotograph maps, vineyards have decreased by 3651 ha in the last 10 years; based on data from the RPGV, vineyards have decreased by 1192 ha in the last 10 years (Table 4.1).

In 2007 in Slovenia, 37% of vineyards were located on terraces (in 2011 only 34.9% and in 2016 only 31%): in the Drava Valley 24% (1757 ha), in the Sava Valley 27% (824 ha), and in the Littoral 55% (3759 ha; Štabuc and Hauptman 2008; RPGV 2016) (Tables 4.2 and 4.3).

In some areas in Slovenia, such as the Brkini Hills, the majority of orchards were planted on terraces or terrace slopes by the beginning of the nineteenth century.

4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes |

53 |

Fig. 4.1 Municipalities in Slovenia with terraced vineyards

Table 4.1 Comparison of vineyard land in Slovenia according to orthophotograph maps and according to the register of grape and wine producers (RPGV)

Years |

|

Orthophotograph |

|

Register of grape and wine |

|

Difference |

|

||||

|

|

maps (ha) |

|

|

producers data (RPGV) (ha) |

|

between data (ha) |

||||

2007 |

|

22,951 |

|

|

|

17,192 |

|

|

5759 |

|

|

2011 |

|

21,265 |

|

|

|

15,973 |

|

|

5292 |

|

|

2016 |

|

19,300 |

|

|

|

16,000 |

|

|

3300 |

|

|

Table 4.2 |

Comparison |

of vineyards located on terraces in the three wine-growing regions in |

|||||||||

Slovenia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Wine-growing |

|

2007 |

2007 |

2011 |

2011 |

|

2016 |

2016 |

|||

regions |

|

|

|

(%) |

(ha) |

(%) |

(ha) |

|

(%) |

(ha) |

|

Drava Valley |

|

24 |

1757 |

22.7 |

1659 |

|

20 |

1254 |

|||

Sava Valley |

|

27 |

824 |

25.5 |

769 |

|

20 |

533 |

|||

Littoral |

|

|

|

55 |

3759 |

54.3 |

3571 |

|

49 |

3035 |

|

Slovenia |

|

|

|

37 |

6340 |

34.9 |

5980 |

|

31 |

4822 |

|

Sources Štabuc and Hauptman (2008), RPGV (2016)

54

Table 4.3 Comparison of vineyards located on terraces in nine wine districts in Slovenia

L. Ažman Momirski

Wine districts |

2007 (ha) |

2011 (ha) |

2016 (ha) |

Prekmurje |

4 |

4 |

2 |

Styria |

35 |

24 |

21 |

Bizeljsko-Sremič |

42 |

34 |

27 |

Lower Carniola |

27 |

18 |

15 |

White Carniola |

27 |

23 |

20 |

Gorizia Hills |

81 |

80 |

80 |

Vipava Valley |

66 |

65 |

59 |

Karst Plateau |

14 |

13 |

10 |

Slovenian Istria |

30 |

21 |

20 |

Sources Škvarč and Kodrič (2008), Mavrič Štrukelj et al. (2012), RPGV (2016)

Here, orchard cultivation goes back to the late eighteenth century, when it was primarily promoted by teachers and parish priests (Volk et al. 2011).

A total of 8900 ha of orchards are found in Slovenia today, and intensive cultivation takes place in just over 4000 ha of orchards. There are two categories for orchards in the Slovenian land-use classification. The first is intensive orchards (category 1221), which are areas planted with only one type of fruit, except for mixed plantations of peaches and nectarines, and mixed plantations of hazelnuts, walnuts, and almonds. Farmers use modern intensive technologies to cultivate intensive orchards. The area of an intensive orchard plantation covers all plantation land together with turning areas, tracks, embankments, and other associated land. If there are more than fifty fruit trees per hectare on the land and if this plantation is not an intensive orchard, then this land is listed under land-use category 1222: extensive orchards. Natural conditions in Slovenia allow the production of mixed fruit, but apples are still the leading type of fruit (Ministry of Agriculture and Environment 2016). Only a small share of apples is grown on terraces (15.7%). The share of terraced orchards in Slovenia is higher for figs (58.1%), apricots (47.7%), cherries (47.6%), persimmons (40.7%), and chestnuts (23.7%; Škvarč and Kodrič 2007).

According to agricultural recommendations, grapevines in a terraced vineyard may be arranged as follows (terrace cross section; Ažman Momirski et al. 2007):

–Single-row terraces (the terrace platform width is 230–280 cm);

–Double-row terraces (the terrace platform width is 300–360 cm);

–Double-row terraces with a passage for a tractor between the row and the slope (the terrace platform width is 430–530 cm); and

–Multi-row terraces (the terrace platform width is 500–620 cm).

The slope and width of the terrace platform affect the width of the terraces and the height and length of the terrace slopes. The terrace platforms have a longitudinal inclination from 0.5 to 5%, which allows excess rainwater to slowly drain from vineyard terraces along their length, preventing falling of slopes, landslides,

4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes |

55 |

erosion, and drifting of slopes. According to agricultural recommendations, the usual length of a vineyard terrace is from 80 to 150 m (Vršič and Lešnik 2005).

Orchards on terraces can be arranged as follows (terrace cross section; Ažman Momirski et al. 2007):

–Single-row terraces with trees planted at the edge of the terrace platform (the terrace platform width is 300–650 cm); and

–Single-row terraces with trees planted on the terrace slope (the terrace platform width is 200–250 cm).

In some areas in Slovenia, planting trees on the terrace slopes is usual because it increases their stability.

The construction of terrace slopes can be divided into three basic categories:

–Dry stone wall construction (traditional terraces);

–Slopes reinforced with stones that were grubbed out during cultivation of farmland, and later covered with earth and grassed over (traditional terraces); and

–Grassed terrace slopes (modern terraces based on traditional terraces; modern terraces).

In some areas, it is difficult to distinguish between dry stone walls that divide property and the slopes of the terraces. Dry stone wall construction can be found in the Koper Hills, the Karst Plateau, and some places in the Alpine region (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2 Overgrown and deteriorating dry stone terrace walls in Krkavče in the Koper Hills, and new terrace construction and grassed terrace slopes in Medana in the Gorizia Hills. Photo Lučka Ažman Momirski

56 |

L. Ažman Momirski |

Fig. 4.3 Grassed terrace slopes in vineyards in Medana in the Gorizia Hills (Photo Lučka Ažman Momirski), in an olive grove in Krkavče in the Koper Hills (Photo Lučka Ažman Momirski), and in meadows and pastures in Artviže in the Brkini Hills (Photo Kras in Brkini) and the Materija Lowland (Photo Matevž Lenarčič)

Grassed terrace slopes are much more common in the cultural Slovenian landscape than dry stone wall construction and can be found in all Slovenian regions (Fig. 4.3).

Terraces can be also categorized by cultivation extent or state of decay:

–Cultivated terraces;

–Partly abandoned terraces; and

–Abandoned terraces.

The terraced landscape contributes to the identity and profile of local cultures. It is an important part of the quality of people’s lives, providing variety and making the region attractive, and in this way making possible the preservation of the settlements and vitality of rural areas (Ažman Momirski 2008a, b, c, d). In this connection, terraces are often recognized as significant landscape features. Terraces with minor or medium significance are a very common feature in Slovenia.