- •Understanding Why Communication Matters

- •Communicating as a Professional

- •Exploring the Communication Process

- •Committing to Ethical Communication

- •Communicating in a World of Diversity

- •Using Technology to Improve Business Communication

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Understanding the Three-Step Writing Process

- •Analyzing the Situation

- •Gathering Information

- •Selecting the Right Medium

- •Organizing Your Message

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Adapting to Your Audience: Building Strong Relationships

- •Adapting to Your Audience: Controlling Your Style and Tone

- •Composing Your Message: Choosing Powerful Words

- •Composing Your Message: Creating Effective Sentences

- •Composing Your Message: Crafting Coherent Paragraphs

- •Using Technology to Compose and Shape Your Messages

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Revising Your Message: Evaluating the First Draft

- •Revising to Improve Readability

- •Editing for Clarity and Conciseness

- •Using Technology to Revise Your Message

- •Producing Your Message

- •Proofreading Your Message

- •Distributing Your Message

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Electronic Media for Business Communication

- •Social Networks

- •Information and Media Sharing Sites

- •Instant Messaging and Text Messaging

- •Blogging

- •Podcasting

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Strategy for Routine Requests

- •Common Examples of Routine Requests

- •Strategy for Routine Replies and Positive Messages

- •Common Examples of Routine Replies and Positive Messages

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Using the Three-Step Writing Process for Negative Messages

- •Using the Direct Approach for Negative Messages

- •Using the Indirect Approach for Negative Messages

- •Sending Negative Messages on Routine Business Matters

- •Sending Negative Employment Messages

- •Sending Negative Organizational News

- •Responding to Negative Information in a Social Media Environment

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Using the Three-Step Writing Process for Persuasive Messages

- •Developing Persuasive Business Messages

- •Common Examples of Persuasive Business Messages

- •Developing Marketing and Sales Messages

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Applying the Three-Step Writing Process to Reports and Proposals

- •Supporting Your Messages with Reliable Information

- •Conducting Secondary Research

- •Conducting Primary Research

- •Planning Informational Reports

- •Planning Analytical Reports

- •Planning Proposals

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Writing Reports and Proposals

- •Writing for Websites and Wikis

- •Illustrating Your Reports with Effective Visuals

- •Completing Reports and Proposals

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Finding the Ideal Opportunity in Today’s Job Market

- •Planning Your Résumé

- •Writing Your Résumé

- •Completing Your Résumé

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Submitting Your Résumé

- •Understanding the Interviewing Process

- •Preparing for a Job Interview

- •Interviewing for Success

- •Following Up After an Interview

- •Chapter Review and Activities

- •Test Your Knowledge

- •Apply Your Knowledge

- •Practice Your Skills

- •Expand Your Skills

- •References

- •Index

66 Unit 2: The Three-Step Writing Process

5 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain why good organization is important to both you and your audience, and explain how to organize any business message.

Organizing Your Message

The ability to organize messages effectively is a skill that helps readers and writers alike. Good organization helps your readers in at least three ways:

■It helps your audience understand your message. By making your main idea clear and supporting it with logically presented evidence, you help audiences grasp the essential elements of your message.

Good organization benefits your audiences by helping them understand and accept your message in less time.

Good organization helps you by reducing the time and creative energy needed to create effective messages.

To organize any message,

■Define your main idea

■Limit the scope

■Choose the direct or indirect approach

■Outline your information in a logical sequence

■It helps your audience accept your message. Careful organization also helps you select and arrange your points in a diplomatic way that can soften the blow of unwelcome news or persuade skeptical readers to see your point of view. In contrast, a poorly organized message can trigger negative emotions that prevent people from seeing the value of what you have to say.

■It saves your audience time. Good organization saves readers time because they don’t have to wade through irrelevant information, seek out other sources to fill in missing information, or struggle to follow your train of thought.

In addition to saving time and energy for your readers, good organization saves you time and consumes less of your creative energy. Having a good organizational plan before you start writing helps the words flow because you can focus on how you want to say something, rather than struggling with what you want to say next. (In fact, whenever you struggle with “writer’s block,” step back and think about the organization of your message. Chances are what you’re really facing is a thinking block, not a writing block.) A clear plan also helps you avoid composing material you don’t need, and it minimizes the time you have to spend revising your first draft.

Good organizational skills are also good for your career. When you develop a reputation as a clear thinker who cares about your readers and listeners, people will be more inclined to pay attention to what you have to say.

That said, what exactly is good organization? You can think of it as structuring messages in a way that helps recipients get all the information they need while requiring the least amount of time and energy for everyone involved. Good organization starts with a clear definition of your main idea.

|

|

Defining Your Main Idea |

||

The topic is the broad subject; the |

The topic of your message is the overall subject, and your main idea is a specific statement |

|||

main idea makes a statement about |

about that topic. For example, if you believe that the current system of using paper forms |

|||

the topic. |

||||

for filing employee insurance claims is expensive and slow, you might craft a message in |

||||

|

|

|||

|

|

which the topic is employee insurance claims and the main idea is that a new web-based |

||

|

|

claim-filing system would reduce costs for the company and reduce reimbursement delays |

||

|

|

for employees. |

|

|

In some instances, you’ll need to |

In longer documents and presentations, you may need to unify a mass of material with |

|||

do some work up front to determine |

a main idea that encompasses all the individual points you want to make. Sometimes you |

|||

what the main idea of a message |

||||

won’t even be sure what your main idea is until you sort through the information. For tough |

||||

really should be. |

||||

|

|

assignments like these, consider a variety of techniques to generate creative ideas: |

||

|

|

■ Brainstorming. Working alone or with others, generate as many ideas and questions as |

||

|

|

you can, without stopping to criticize or organize. After you capture all these pieces, look |

||

|

|

|

for patterns and connections to help identify the main idea |

|

|

REAL-TIME UPDATES |

|||

|

and the groups of supporting ideas. |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

Learn More by Watching This Presentation |

■ Journalistic approach. The journalistic approach asks who, |

||

|

|

|

what, when, where, why, and how questions to distill major |

|

|

|

|

||

Smart advice for brainstorming sessions

thoughts from unorganized information.

Generate better ideas in less time with these helpful tips. Go to http://real-timeupdates.com/bce6 and click on Learn More. If you are using MyBCommLab, you can access Real-Time Updates within each chapter or under Student Study Tools.

■Question-and-answer chain. Start with a key question the audience is likely to have, and work back toward your message. In most cases, you’ll find that each answer generates new questions, until you identify the information that needs to be in your message.

Chapter 3: Planning Business Messages |

67 |

■Storyteller’s tour. Some writers find it helpful to talk through a communication challenge before trying to write. Record yourself as you describe what you intend to write. Then listen to the playback, identify ways to tighten and clarify the message, and repeat the process until you distill the main idea down to a single, concise message.

■Mind mapping. You can generate and organize ideas by using a graphic method called mind mapping. Start with a main idea and then branch out to connect every other related idea that comes to mind. The Real-Time Updates Learn More item on the previous page offers links to a variety of mind-mapping tools.

Limiting Your Scope

The scope of your message is the range of information you present, the overall length, and the level of detail—all of which need to correspond to your main idea. The length of some business messages has a preset limit, whether from a boss’s instructions, the technology you’re using, or a time frame such as individual speaker slots during a seminar. However, even if you don’t have a preset length, limit your scope to the minimum amount of information needed to convey your main idea (see Figure 3.7).

In addition to limiting the overall scope of your message, limit the number of major supporting points to a half dozen or so—and if you can get your idea across with fewer points, all the better. Listing 20 or 30 supporting points might feel as though you’re being thorough, but your audience is likely to view such detail as rambling and mind numbing. Instead, group your supporting points under major headings, such as finance, customers, competitors, employees, or whatever is appropriate for your subject. Look for ways to distill your supporting points so that you have a smaller number with greater impact.

Limit the scope of your message so that you can convey your main idea as briefly as possible.

The site’s navigation is designed to let individual audience segments (in this case, content providers), find messages that address their unique concerns.

Figure 3.7 Limiting the Scope of a Message

The Blu-ray Disc Association is the industry consortium that oversees the technical standards and other matters related to Blu-ray discs used for movies, music, and data storage. In this section of its website, the association describes the benefits of the Blu-ray format, with a separate message for each of four stakeholder groups. This particular screen describes the benefits for one of those groups (content providers, such as movie studios). Notice how the scope of the message is limited to supporting a single main idea—the business benefits of Blu-ray for this specific audience.

The first paragraph states the main idea, that Blu-ray is the ideal format for highdefinition media content.

Each of the next four paragraphs focuses on one major supporting point, with carefully chosen details to back up each supporting point—without overloading the reader with too much detail or irrelevant information.

Source: Blu-Ray Disc Association.

68 Unit 2: The Three-Step Writing Process

The number of words, pages, or minutes you need in order to communicate and support your main idea depends on your topic, your audience members’ familiarity with the material and their receptivity to your conclusions, and your credibility. You’ll need fewer words to present routine information to a knowledgeable audience that already knows and respects you. You’ll need more words to build a consensus about a complex and controversial subject, especially if the members of your audience are skeptical or hostile strangers.

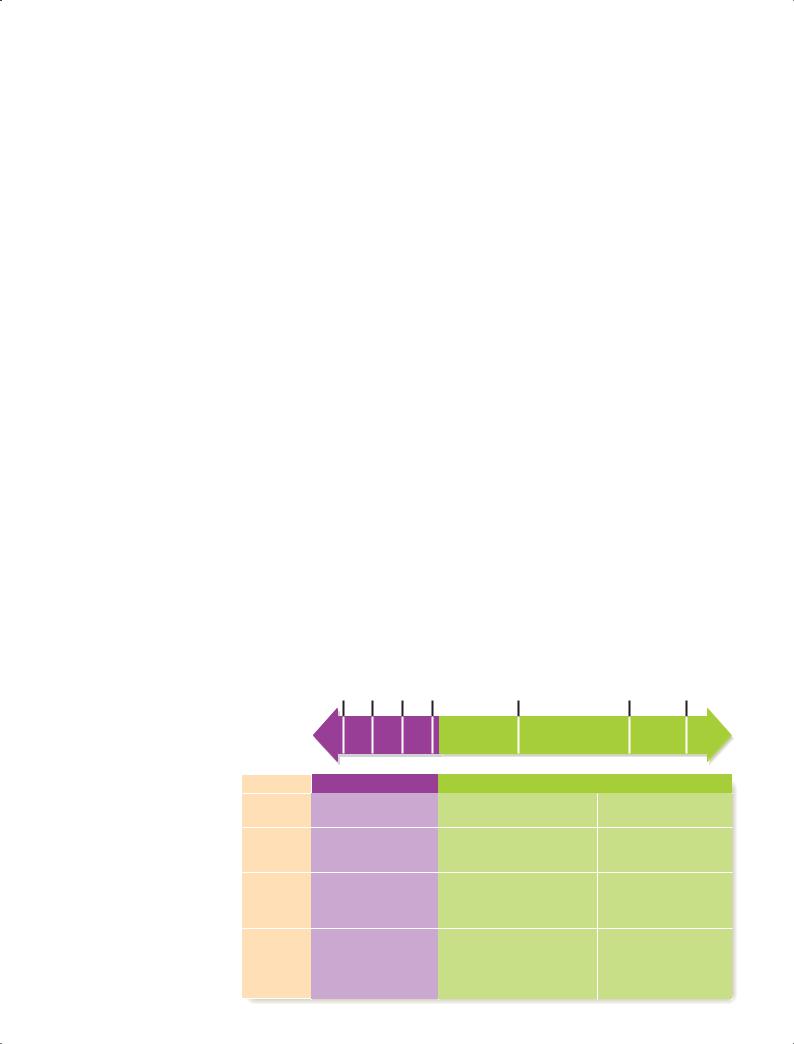

With the direct approach, you open with the main idea of your message and support it with reasoning, evidence, and examples.

With the indirect approach, you withhold the main idea until you have built up to it logically and persuasively with reasoning, evidence, and examples.

Choosing Between Direct and Indirect Approaches

After you’ve defined your main idea and supporting points, you’re ready to decide on the sequence you will use to present your information. You have two basic options:

■Direct approach. When you know your audience will be receptive to your message, use the direct approach: Start with the main idea (such as a recommendation, conclusion, or request) and follow that with your supporting evidence.

■Indirect approach. When your audience will be skeptical about or even resistant to your message, you generally want to use the indirect approach: Start with the evidence first and build your case before presenting the main idea. Note that taking the indirect approach does not mean avoiding tough issues or talking around in circles. It simply means building up to your main idea in a logical or sensitive way.

To choose between these two alternatives, analyze your audience’s likely reaction to your purpose and message, as shown in Figure 3.8. Bear in mind, however, that Figure 3.8 presents only general guidelines; always consider the unique circumstances of each message and audience situation. The type of message also influences the choice of the direct or indirect approach. In the coming chapters, you’ll get specific advice on choosing the best approach for a variety of different communication challenges.

Outlining takes some time and effort, but it can often save you considerable time and effort in the composing and revising stages.

Outlining Your Content

After you have chosen the direct or indirect approach, the next task is to figure out the most logical and effective way to present your major points and supporting details. Even if you’ve resisted creating outlines in your school assignments over the years, get into the habit of creating outlines when you’re preparing most business messages. You’ll save time, get better results, and do a better job of navigating through complicated situations.

Figure 3.8 Choosing Between the Direct and Indirect Approaches

Think about the way your audience is likely to respond before choosing your approach.

|

InterestedPleased Neutral |

Displeased |

ested |

Unwilling |

Eager |

Uninter |

|

Direct Approach |

Indirect Approach |

|

Audience |

Eager/interested/ |

Displeased |

Uninterested/unwilling |

Reaction |

pleased/neutral |

|

|

Message |

Start with the main |

Start with a neutral statement |

Start with a statement or |

Opening |

idea, the request, or |

that acts as a transition to the |

question that captures |

|

the good news. |

reasons for the bad news. |

attention. |

Message |

Provide necessary |

Give reasons to justify a |

Arouse the audience’s |

Body |

details. |

negative answer. State or |

interest in the subject. |

|

|

imply the bad news, and |

Build the audience’s |

|

|

make a positive suggestion. |

desire to comply. |

Message |

Close with a cordial |

Close cordially. |

Request action. |

Close |

comment, a reference |

|

|

|

to the good news, or a |

|

|

|

statement about the |

|

|

|

specific action desired. |

|

|

Chapter 3: Planning Business Messages |

69 |

The particular message is divided into two major points (I and II)

I. First major point

A.First subpoint

B.Second subpoint  Subpoint B is

Subpoint B is

1. |

Examples and evidence |

supported with |

The first major |

2. |

Examples and evidence |

three sets of |

|

examples and |

point is divided |

||

|

a. Detail |

evidence (1,2, |

into three |

|

and 3), the second |

subpoints |

|

|

b. Detail |

of which is further |

(A, B, and C) |

|

subdivided with |

|

|

|

|

|

3.Examples and evidence  two detail sections

two detail sections

C. Third subpoint

II. Second major point

A.First subpoint

1.Examples and evidence

2.Examples and evidence

B.Second subpoint

Figure 3.9 Structuring an Outline

No matter what outlining format you use, think through your major supporting points and the examples and evidence that can support each point.

You’re no doubt familiar with the basic outline formats that identify each point with a number or letter and that indent certain points to show which ones are of equal status. A good outline divides a topic into at least two parts, restricts each subdivision to one category, and ensures that each subdivision is separate and distinct (see Figure 3.9).

Whichever outlining or organizing scheme you use, start by stating your main idea; you then list your major supporting points and follow with examples and evidence:

■Start with the main idea. The main idea helps you establish the goals and general strategy of the message, and it summarizes (1) what you want your audience members to do, think, or feel after receiving the message and (2) why it makes sense for them to do so. Everything in your message should either support the main idea or explain its implications. (Remember that if you choose the indirect approach, the main idea will appear toward the end of your message, after you’ve presented your major supporting points.)

■State the major points. Support your main idea with the major points that clarify and explain your ideas in more concrete terms. If your purpose is to inform and the material is factual, your major points may be based on something physical or financial, for example—something you can visualize or measure, such as activities to be performed, functional units, spatial or chronological relationships, or parts of a whole. When you’re describing a process, the major points are usually steps in the process. When you’re describing an object, the major points often correspond to the parts of the object. When you’re giving a historical account, major points represent events in the chronological chain of events. If your purpose is to persuade or to collaborate, select major points that develop a line of reasoning or a logical argument that proves your central message and motivates your audience to act.

■Provide examples and evidence. After you’ve defined the main idea and identified major supporting points, you’re ready to back up those points with examples and evidence that help audience members understand, accept, and

remember your message. Choose your examples and evidence carefully. You want to be compelling and complete but also as concise as possible. One strong example or piece of evidence can be more effective than three or four weaker items.

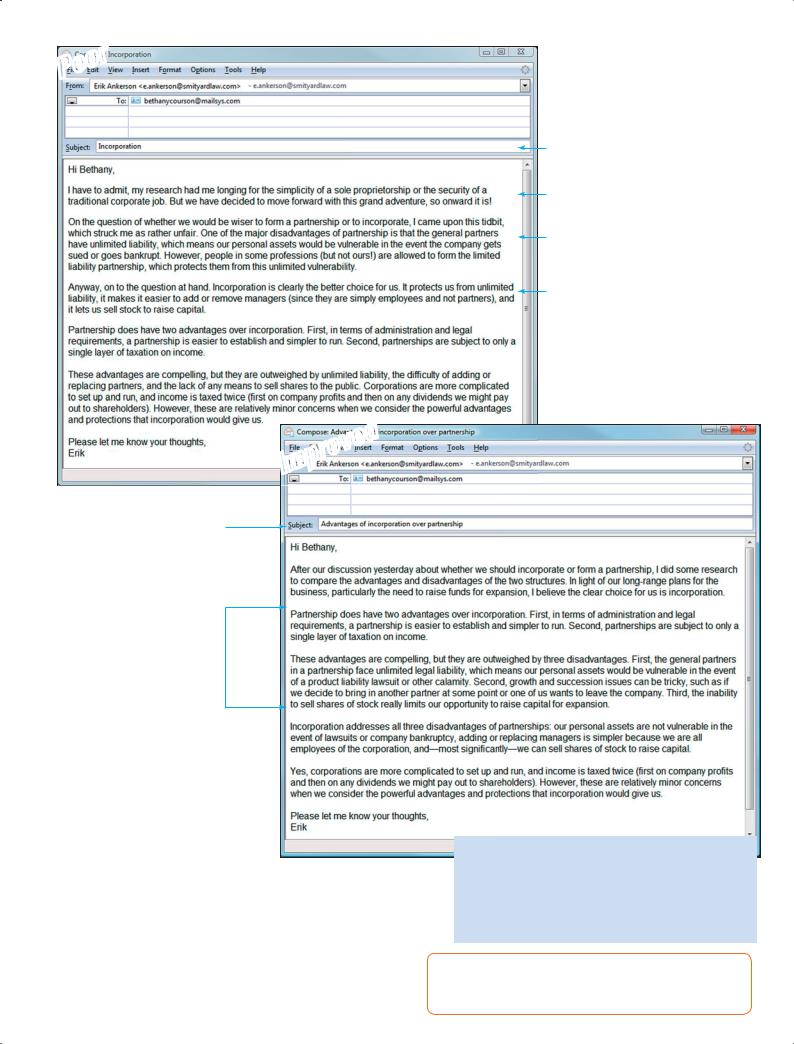

Figure 3.10 on the next page illustrates several of the key themes about organizing a message: helping readers get the information they need quickly, defining and conveying the main idea, limiting the scope of the message, choosing the approach, and outlining your information.

Choose supporting points, evidence, and examples carefully; a few strong points will make your case better than a large collection of weaker points.

Poor

This vague subject line offers few clues about the topic of the message.

The email starts off with an irrelevant discussion, doesn’t explain what research this refers to,

and fails to introduce the topic of the message.

This paragraph introduces the topic but then shifts to an irrelevant discussion (it makes a good point about unlimited liability, but the point is buried in irrelevant material).

The main idea, that the pair should incorporate, is buried in the middle of the message.

By jumping from partnership to incorporation, back to partnership, and then back to incorporation again throughout the course

of the message, the writer forces the reader to piece together the comparative

evidence herself.

Improved

The subject line states the topic (incorporation vs. partnership) and the main idea (incorporation is the better choice).

The opening provides a context  by referring to a previous conversation

by referring to a previous conversation

and then states the main idea.

These two paragraphs support the main idea by showing how the disadvantages of partnerships outweigh the advantages.

The writer continues to provide support by explaining how incorporation overcomes  all three key disadvantages of partnerships.

all three key disadvantages of partnerships.

The comparison is completed by  identifying two disadvantages of incorporation

identifying two disadvantages of incorporation

but noting that they are outweighed by the advantages.

Figure 3.10 Improving the Organization of a Message

This writer is following up on a conversation from the previous day, in which he and the recipient discussed which of two forms of ownership, a partnership or a corporation, they should use for their new company. (Partnership has a specific legal meaning in this context.) That question is the topic of the message; the main idea is the recommendation that they incorporate, rather than form a partnership. Notice how the Improved version uses the direct approach to quickly get to the main idea and then supports that by comparing the advantages and disadvantages of both forms of ownership. In contrast, the Poor version contains irrelevant information, makes the comparison difficult to follow, and buries the main idea in the middle of the message.

Pointers for Good Organization

ss Get to the topic of the message quickly; don’t make the reader guess what the message is about.

ssStart with the main idea and then support it (direct approach) or build up to the main idea at the end (indirect approach).

ss Group related ideas and present them in a logical order.

ssInclude only the information needed to convey and support your main idea.

MyBCommLab Apply Figure 3.10’s key concepts. Go to mybcommlab.com and follow this path: Course Content Chapter 3 DOCUMENT MAKEOVERS

71

Building Reader Interest with Storytelling Techniques

Storytelling might seem like an odd subject for a business course, but stories can be an effective way to organize messages in a surprising number of business communication scenarios, from recruiting and training employees to enticing investors and customers. Storytelling is such a vital means of communicating that, in the words of management consultant Steve Tobak, “It’s hard to imagine your career going anywhere if you can’t tell a story.”10 Fortunately, you’ve been telling stories all your life, so narrative techniques already come naturally to you; now it’s just a matter of adapting those techniques to business situations.

Moreover, you’ve already been on the receiving end of thousands of business stories— storytelling is one of the most common structures used in television commercials and other advertisements. People love to share stories about themselves and others, too, which makes social media ideal for storytelling.11

Career-related stories, such as how someone sought and found the opportunity to work on projects he or she is passionate about, can entice skilled employees to consider joining a firm. Established companies often tell the stories of their early days to highlight their depth of experience or core values (see Figure 3.11). Entrepreneurs use stories to help investors see how their new ideas have the potential to affect people’s lives (and therefore generate lots of sales). Stories can be cautionary tales as well, dramatizing the consequences of career blunders, ethical mistakes, and strategic missteps.

A key reason storytelling can be so effective is that stories help readers and listeners imagine themselves living through the experience of the person in the story. As a result, people tend to remember and respond to the message in

ways that can be difficult to achieve with other forms of communication.

In addition, stories can demonstrate cause-and-effect relationships in a compelling fashion.12 Imagine attending an employee orientation and listening to the trainer read off a list of ethics rules and guidelines. Now imagine the trainer telling the story of someone who sounded a lot like you, fresh out of college and full of energy and ambition. Desperate to hit demanding sales targets, the person in the story began entering transactions before customers had actually agreed to purchase, hoping the sales would eventually come through and no one would be the wiser. However, the

scheme was exposed during a routine audit, and the rising star was booted out of the company with an ethical stain that would haunt him for years. You may not remember all the rules and guidelines, but chances are you will remember what happened to that person who sounded a lot like you.

A classic story has three basic parts. The beginning of the story presents someone with whom the audience can identify in some way, and this person has a dream to pursue or a problem to solve. (Think of how movies and novels often start by introducing a likable character who immediately gets into danger, for example.) The middle of the story shows this character taking action and making decisions as he or she pursues the goal or tries to solve the problem.