- •Англійська мова для професійного спілкування

- •Передмова

- •Brief contents

- •Unit 1 structure and bonding

- •1. You are going to read three texts which are all connected with chemistry. Read the texts and be able to make intelligent guesses about:

- •2. Decide what books the texts come from. What helped you to make up your mind? Choose from the following:

- •3. Which sentence could be the opening sentence of the text?

- •4. Think about the first sentences above and decide which you think are likely to introduce a paragraph with:

- •6. Give the definitions of the following terms:

- •2. Look at Appendix 3 and Render the following text.

- •3. Read the following text. Discuss the point with your colleagues. What do you know about the methods of scientific investigation? The Scientific Method

- •The Scientific Method

- •1. Culture clips: London life

- •2.What museums are there in your city/town? Have you ever visited any?

- •3.Have you ever visited science museum of the “kpi”? Are there any in your university? Imagine that you are a guide at such museum, tell about the most interesting museum piece.

- •2. What was said in the text about:

- •3. Render the following text.

- •1. Imagine that you are starting a presentation. What phrases might you use?

- •2. Listen totwowaysofopeningpresentationsandseeifyoucanhearsomeofthephrasesabove.

- •3. Read some advices on delivering effective presentations in the Appendix 7 and write your own opening for the topic “Stereochemistry”.

- •Imagine that you are a major distributor of the following product. Look at Business English section and write a letter asking more information about the product presented below.

- •Unit 3 molecular symetry

- •2. Find five things in the texts to finish the sentence: “It reminds me of…”

- •2. Read the flowcharts given in the figure 1 and 2.

- •3. Read some information about creation of the flow charts in the Appendix 4-6 and create your own describing any experiment you made in the laboratory.

- •4. Create a list of rules related to the theme of the text given in the exercise 1. Share and compare the rules with your partners and think how they might be improved, choose the best ones.

- •5. Render the text given in the exercise 1.

- •2. Listen to two ways of giving presentations and see if you can hear some of the phrases above.

- •3. Read some advices on delivering effective presentations in the Appendix 7 and write your own presentation for the topic “Molecular symmetry”.

- •You ordered: Beckman du64 uv/VisSpectrophotometer

- •Unit 4 stereochemistry of reactions

- •Chiral Drug

- •1.Presentation: questions.

- •Unit 5 resolution of enantiomers

- •Resolution of enantiomers

- •1. Method of resolution is the title of the text in this section. What is the likely content of the article? Predict the methods which might be described.

- •3. Mark and talk about five things from the text you are glad to find out about. Talk in pairs about these things and why you chose them.

- •5.Render the text.

- •4. Think of three reasons you liked the text and three reasons you didn’t like it. Share and compare your reasons with other students. Find out how many other students share your opinion.

- •1.Presentation: useful tips.

- •3.Complete the sentence with the correct phrase.

- •Principles of Stereochemistry

- •Enantiomeric Relationships

- •Diastereomeric Relationships

- •Methods of determining configuration

- •The Cause of Optical Activity

- •Molecules With More Than One Chiral (Stereogenic) Center

- •Asymmetric Synthesis

- •Business english

- •Formal letter

- •1.Titles and addresses

- •2Covering the issues

- •3 Beginning your letter

- •4 Ordering ideas

- •5 Range

- •6 Ending the letter

- •Sample formal letter

- •Informal letter or email

- •1 Titles and addresses

- •2 Openings

- •3 Covering all the issues

- •4 Using informal language

- •5 Range

- •6 Connectors

- •7 Closing statements

- •Writing a tactful advice letter

- •How to write a request letter

- •Complaint letter

- •If necessary, add any further information:

- •Writing claim letter

- •Inquiry letter

- •Establish Your Objective

- •Determine Your Scope

- •Organize Your Letter

- •Draft Your Letter

- •Close Your Letter

- •Review and Revise Your Inquiry Letter

- •Sample Inquiry Letter __________Better Widget Makers, Inc.__________

- •5555 Widget Avenue

- •Appendices appendix 1 exclamations

- •Appendix 2 general conversation gambits

- •Appendix 3 the scheme of rendering the text

- •Appendix 4 flow charts

- •Appendix 5 graph

- •Appendix 6 reading and interpreting graphs

- •Types of Graphs

- •Appendix 7 presentations

- •Typescripts

- •Bbc Learning English. Talking Business

- •(Bbclearningenglish. Com)

- •Bibliography 1

- •Bibliography 2

3. Mark and talk about five things from the text you are glad to find out about. Talk in pairs about these things and why you chose them.

Which method do you find:

the easiest;

the most complex;

the most interesting;

to be common;

to be widespread.

5.Render the text.

Speaking

Using conversational gambits given in the Appendix 2 construct a dialogue “The best method of resolution”.

What my folks know: In pairs, talk about how much you think your family and friends know about enantiomers and how interested they are (or otherwise). Report on what your partner said.

|

|

Level of interest |

Level of knowledge |

|

Partner |

|

|

|

Parents |

|

|

|

Siblings |

|

|

|

Grandparents |

|

|

|

Best friend |

|

|

|

Workmate |

|

|

|

Other |

|

|

3. Read the following text. Discuss whether what they came up with is really so difficult, why the subject of the text may not be as easy as it seems. Share and compare your opinion with partners.

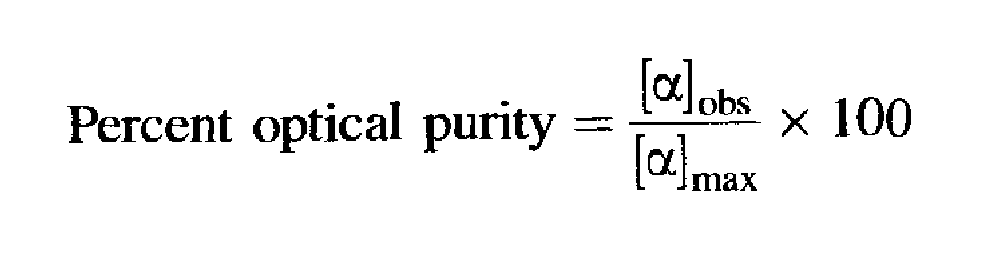

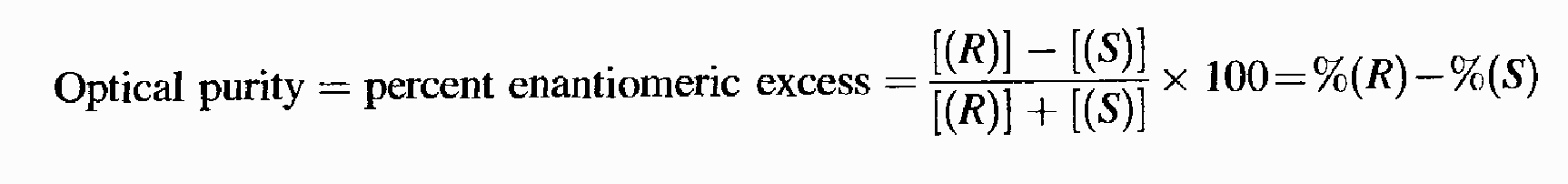

Optical Purity

Suppose we have just attempted to resolve a racemic mixture by one of the methods described in the previous section. How do we know that the two enantiomers we have obtained are pure? For example, how do we know that the ( + ) isomer is not contaminated by, say, 20% of the (-) isomer and vice versa? If we knew the value of [ɑ] for the pure material, [ɑ]max, we could easily determine the purity of our sample by measuring its rotation. For example, if [ɑ]max is +80° and our ( + ) enantiomer contains 20% of the (-) isomer, [ɑ] for the sample will be +48°. We define optical purity as

Assuming a linear relationship between [ɑ]max and concentration, which is true for most cases, the optical purity is equal to the percent excess of one enantiomer over the other:

But how do we determine the value of [a]max? It is plain that we have two related problems here; namely, what are the optical purities of our two samples and what is the value of [ɑ]max. If we solve one, the other is also solved. Several methods for solving these problems are known.

One of these methods involves the use of NMR. Suppose we have a nonracemic mixture of two enantiomers and wish to know the proportions. We convert the mixture into a mixture of diastereomers with an optically pure reagent and look at the NMR spectrum of the resulting mixture, for example,

If we examined the NMR spectrum of the starting mixture, we would find only one peak (split into a doublet by the C—H) for the Me protons, since enantiomers give identical NMR spectra. But the two amides are not enantiomers and each Me gives its own doublet. From the intensity of the two peaks, the relative proportions of the two diastereomers, and hence of the original enantiomers, can be determined. Alternatively, the "unsplit" OMe peaks could have been used. This method was satisfactorily used to determine the optical purity of a sample of l-phenylethylamine (the case shown above), as well as other cases, but it is obvious that sometimes corresponding groups in diastereomeric molecules will give NMR signals that are too close together for resolution. In such cases, one may resort to the use of a different optically pure reagent. The 13C NMR can be used in a similar manner. It is also possible to use these spectra to determine the absolute configuration of the original enantiomers by comparing the spectra of the diastereomers with those of the original enantiomers. From a series of experiments with related compounds of known configurations it can be determined in which direction one or more of the 1H or 13C NMR peaks are shifted by formation of the diastereomer. It is then assumed that the peaks of the enantiomers of unknown configuration will be shifted the same way.

A closely related method does not require conversion of enantiomers to diastereomers but relies on the fact that (in principle, at least) enantiomers have different NMR spectra in a chiral solvent, or when mixed with a chiral molecule (in which case transient diastereomeric species may form). In such cases, the peaks may be separated enough to permit the proportions of enantiomers to be determined from their intensities. Another variation, which gives better results in many cases, is to use an achiral solvent but with the addition of a chiral lanthanide shift reagent such as tris[3-trifiuoroacetyl-J-camphorato]europium(III). Lanthanide shift reagents have the property of spreading NMR peaks of compounds with which they can form coordination compounds, for examples, alcohols, carbonyl compounds, amines, and so on. Chiral lanthanide shift reagents shift the peaks of the two enantiomers of many such compounds to different extents.

Another method, involving gas chromatography, is similar in principle to the NMR method. A mixture of enantiomers whose purity is to be determined is converted by means of an optically pure reagent into a mixture of two diastereomers. These diastereomers are then separated by gas chromatography (GC) and the ratios determined from the peak areas. Once again, the ratio of diastereomers is the same as that of the original enantiomers. High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been used in a similar manner and has wider applicability. The direct separation of enantiomers by gas or liquid chromatography on a chiral column has also been used to determine optical purity.

Other methods involve isotopic dilution, kinetic resolution, 13C NMR relaxation rates of diastereomeric complexes, and circular polarization of luminescence.