- •Table of contents

- •Abbreviations and Acronyms

- •Executive summary

- •Introduction

- •Institutional arrangements for tax administration

- •Key points

- •Introduction

- •The revenue body as an institution

- •The extent of revenue body autonomy

- •Scope of responsibilities of the revenue body

- •Special governance arrangements

- •Special institutional arrangements for dealing with taxpayers’ complaints

- •Bibliography

- •The organisation of revenue bodies

- •Getting organised to collect taxes

- •Office networks for tax administration

- •Large taxpayer operations

- •Managing the tax affairs of high net worth individuals taxpayers

- •Bibliography

- •Selected aspects of strategic management

- •Key points and observations

- •Managing for improved performance

- •Reporting revenue body performance

- •Summary observations

- •Managing and improving taxpayers’ compliance

- •Bibliography

- •Human resource management and tax administration

- •Key points

- •Aspects of HRM Strategy

- •Changes in policy in aspects of HRM within revenue bodies

- •Staff metrics: Staff numbers and attrition, age profiles and qualifications

- •Resources of national revenue bodies

- •Key points and observations

- •The resources of national revenue bodies

- •Impacts of recent Government decisions on revenue bodies’ budgets

- •Overall tax administration expenditure

- •Measures of relative costs of administration

- •International comparisons of administrative expenditure and staffing

- •Bibliography

- •Operational performance of revenue bodies

- •Key points and observations

- •Tax revenue collections

- •Refunds of taxes

- •Taxpayer service delivery

- •Are you being served? Revenue bodies’ use of service delivery standards

- •Tax verification activities

- •Tax disputes

- •Tax debts and their collection

- •Bibliography

- •The use of electronic services in tax administration

- •Key points

- •Provision and use of modern electronic services

- •Bibliography

- •Tax administration and tax intermediaries

- •Introduction

- •The population and work volumes of tax intermediaries

- •Regulation of tax intermediaries

- •The services and support provided to tax intermediaries

- •Bibliography

- •Legislated administrative frameworks for tax administration

- •Key findings and observations

- •Introduction

- •Taxpayers’ rights and charters

- •Access to tax rulings

- •Taxpayer registration

- •Collection and assessment of taxes

- •Administrative review

- •Enforced collection of unpaid taxes

- •Information and access powers

- •Tax offences (including policies for voluntary disclosures)

- •Bibliography

6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES – 199

Social contributions, which are not collected by the main revenue body in many OECD countries, are a significant source of tax revenue and, in fact, are the predominant source of tax revenue in over half of OECD countries.

The variations in aggregate tax burdens evident from Table 6.1 have a number of implications from a tax administration viewpoint, particularly in the context of international comparisons. The significant variations in tax burden ratios coupled with variations in the mix of direct and indirect taxes mean that there can be quite different administrative workloads and compliance issues from country to country.

Only around half of revenue bodies were able to quantify the data needed to measure the proportion of PIT and SSC collected using withholding mechanisms and for a fair number the data appear inaccurate; for the balance of revenue bodies (e.g. Canada, South Africa, and United States) the ratio tended to be in the range of 80-90%.

Refunds of taxes

A factor given relatively little attention in describing national tax systems and the work of national revenue bodies is the refunds of taxes to taxpayers, and the resultant workload and costs for the revenue body and taxpayers to settle tax liabilities. Given the underlying design of the main taxes administered (i.e. PIT, CIT and VAT) some element of over-payment by a proportion of taxpayers is unavoidable; in fact, for both the PIT and VAT some incidence of refunds is desirable. However, as discussed in this section the overall incidence of refunds taxes (in value terms) for many countries is higher than perhaps generally recognised and varies significantly across countries. Related to this, the relatively high incidence of tax refunds for particular taxes raises a number of important tax system management issues of concern to taxpayers, policy-makers and revenue bodies. Excess tax payments represent a cost to taxpayers in terms of “the time value of money”, which is particularly critical to businesses that are operating with tight margins where cash flow is paramount. Any delays in refunding legitimately overpaid taxes may therefore result in significant “costs” to taxpayers, particularly where there are no or inadequate provisions for the payment of interest to taxpayers in respect of delayed refunds. Another important consideration is that tax regimes with a high incidence of tax refunds are attractive to fraudsters (especially via organised criminal attacks) and for this reason present a significant risk to revenue bodies and necessitate effective risk-based approaches for identifying potentially fraudulent refund claims.

From limited research carried out by the Secretariat, there appear to be a range of factors that can influence the incidence of refunds for each of the major taxes administered

– see Box 6.1. Some or all of these may apply to varying degrees across each of the surveyed countries.

Concerning VAT systems, the combination of factors that result in a relatively high incidence of taxes to be refunded to taxpayers, coupled with a requirement to pay interest on delayed refunds creates a “conflict” for many revenue bodies that must be carefully managed. On the one hand, they must be alert to potentially excessive refund claims taking steps to develop and use sophisticated risk profiling techniques to detect such claims before they are made to claimants validate in such situations, while on the other hand they are under pressure to expeditiously refund amounts of VAT legitimately overpaid which businesses require to fund their operations. These considerations have prompted international and regional tax organisations to give attention to this matter with a view to providing “best practice”

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

200 – 6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES

guidance to revenue bodies, particularly in developing and transitional economies. A useful study of the issues encountered in this field and practical guidance for establishing a system of effective controls is contained in VAT Refunds: A Review of Country Experience, IMF Working Paper WP/05/218 produced by the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

The key observations concerning the incidence of refunds are as follows:

The incidence of tax refunds (for 42 of 52 revenue bodies) varies significantly, reflecting a range of tax system design factors of the kind described in Box 6.1. For 2011;

-12 revenue bodies reported aggregate refunds < 10%;

-15 revenue bodies reported an amount between 10-20%;

-11 revenue bodies reported between 20-30%; and

-4 revenue bodies reported in excess of 30% (i.e. Czech Rep., Poland, Slovakia, and Switzerland) with the Slovak Rep. reporting an abnormally large 66%);.

In overall terms, there is an increasing trend in the proportion of tax being refunded to taxpayers over the period reported, although this trend appears to have been influenced, in part at least, by reduced tax revenues in some countries arising in the aftermath of the global economic crisis;

Box 6.1. Factors that can contribute to the incidence of tax refunds

Personal income tax

Employee withholding schedules (where the non-cumulative approach is used) that are calibrated to marginally “over-withhold” taxes from employees wages, pending the settlement of liabilities in end-of year tax returns;

Tax system design features that result in various tax benefits being delivered to taxpayers via the end-of-year tax return assessment process;

The use of flat rate (creditable) withholding mechanisms for investment income, particularly interest income, that result in “overpayment” of taxes for lower income taxpayers (and that are generally refunded with the filing of a tax return);

Design features of the system for making advance payments of tax (e.g. the base applied for estimating instalments, the threat of penalties for under-estimates) that may discourage some taxpayers from making revised estimates of income prior to filing their end-year tax return;

Taxpayers under-reporting income and/or over-claiming deductions and other entitlements in the end-of-tax return process to inflate their refund entitlements.

Corporate income tax

Reversals of relatively large assessments following the resolution of taxpayers’ disputes, resulting in refunds of overpaid taxes; and

Features of the system for making advance payments of tax (e.g. the base applied for estimating instalments, the threat of penalties for under-estimates) that may discourage some taxpayers from making revised estimates prior to filing their end-year tax return.

Value added tax

The nature of a country’s economy (e.g. the extent of value added of export industries, the proportion of taxable and zero-rated sales in the economy);

Design features of the VAT system, particularly the extent of zero-rating and use of multiple rates; and

Inflated VAT refund claims that go undetected, including those resulting from fraudulent schemes designed to exploit weaknesses in VAT refund controls.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES – 201

Although not researched in detail, data from selected revenue bodies’ annual performance and/or statistical reports indicate that substantial amounts of VAT (i.e. in excess of 20% of annual gross revenue collections) must be refunded, for example;

-Finland: over 40% of gross collections in 2011;

-France: 26.9% of gross collections in 2010;

-Hungary: 40.0% of gross collections in 2010 and 45.9% in 2011;

-New Zealand: 43.9% in 2010/11 and 44.7% in 2011/12;

-Slovakia: VAT refunds in excess of 50% of gross collections in 2010;

-South Africa: 35.9% of gross collections in 2010/11 and 40.7% in 2011/12;

-Spain: VAT refunds of 34.0% (2010) and 36.4% (2011);

-Sweden: VAT refunds of 39% in 2009; and

-United Kingdom: 49.8% in 2010/11 and 49.2% in 2011/12.

While for many of these countries the incidence of VAT refunds can be partly attributed to a high volume of exports, the data nevertheless highlights the importance of revenue bodies having systematic processes in place for granting timely VAT refunds to compliant taxpayers, as well as robust compliance checks in place for the detection of fraudulent VAT registrations and refund claims (ideally before any refunds are paid to claimants).

Around 20% of revenue bodies were unable to quantify the value of refunds, suggesting a possible gap in their normal performance monitoring arrangements.

Taxpayer service delivery

The provision of a comprehensive array of services for taxpayers and their representatives is an important component of the work of revenue bodies given the size of their client base, and the complexity and range of taxes administered, often applying self-assessment principles. However, revenue bodies face many competing demands. With limits on the resources that they can devote to all of their work, careful choices must be made as to how they are to be allocated to achieve the optimal mix of outcomes. As part of this, consideration must also be given to ensuring that service demands are satisfied in the most economical way, meaning the revenue bodies require both a detailed understanding of their service demand volumes and the costs of the various channels used for satisfying such demand.

In 2012, the FTA undertook a study – Working smarter in revenue administration – Using demand management strategies to meet service delivery goals – with the purpose of identifying the demand management processes revenue bodies had in place and the steps they took to understand the root causes of service demand and how that knowledge was applied to either reduce demand or shift it to more cost efficient channels. Among other things the study, which examined the approaches of some 26 (mostly OECD) countries, found that:

Despite having implemented multi-channel service models and setting service objectives to shift taxpayers to self-service and the online channel, many revenue bodies were continuing to experience high demand on their more expensive in-person and inbound call channels.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

202 – 6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES

Most revenue bodies were measuring demand through a variety of methodologies and technologies such as manual processes, call centre and workload control systems and databases that provide useful information on volumes, trends and demand topics; however, these methodologies were typically costly, timeconsuming, labour intensive and, most importantly, not effective for determining the root causes of demand.

Generally speaking, internal revenue body governance processes for managing service demand were immature-fragmented, incomplete, and/or lacking co-ordination

In light of the study’s findings, the FTA commissioned further work in 2012 to provide practical guidance for revenue bodies to assist them meet taxpayers’ service expectations. This work is expected to be published in the second quarter of 2012.

As a follow-on to the FTA’s study and to reinforce the importance of this matter to all revenue bodies, the CIS 2012 survey sought volume data on the main service demand categories of revenue bodies.

Managing service demand-service volumes

Data on the service volumes reported by revenue bodies are set out in Tables 6.3 and 6.4, while Table 6.5 sets out a number of ratios to place the data in a comparative context. The key observations and findings are as follows:

In-person inquiries

Many revenue bodies (over 25%) were unable to quantify the level of demand for this service category suggesting possible weaknesses in their knowledge of this service channel and ability to improve its efficiency.

For revenue bodies where data are available, there are significant variations in the relative levels of in-person inquiries received; using the benchmark “inquiries made/100 citizens” for the 2010 and 2011 fiscal years, a number of countries (e.g. France, Hungary, and Portugal) have an abnormally high incidence of in-person inquiries, suggesting potential to significantly reduce the costs of their “in-person inquiries” channel;

Many revenue bodies with relative high “in-person inquiry” volumes have relatively low “phone telephony” volumes and/or offer in-person payment services, suggesting potential for efficiency gains from increasing use of telephony and Internet services and modern payment services respectively – examples here include Estonia, France, Hungary, and Portugal.

The Canada Revenue Agency has the lowest rate of service demand for this channel, the result of concerted efforts to reduce the costs of this channel; a case study describing how this has been achieved is set out in the aforementioned 2012 FTA report “Working smarter in revenue administration – Using demand management strategies to meet service delivery goals” (p. 34).

On a positive note and as described in Chapter 2 a fair number of revenue bodies are taking steps to significantly scale back the size of their office networks, which might reasonably be expected to lead to large reductions in their “in-person inquiries” volumes.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES – 203

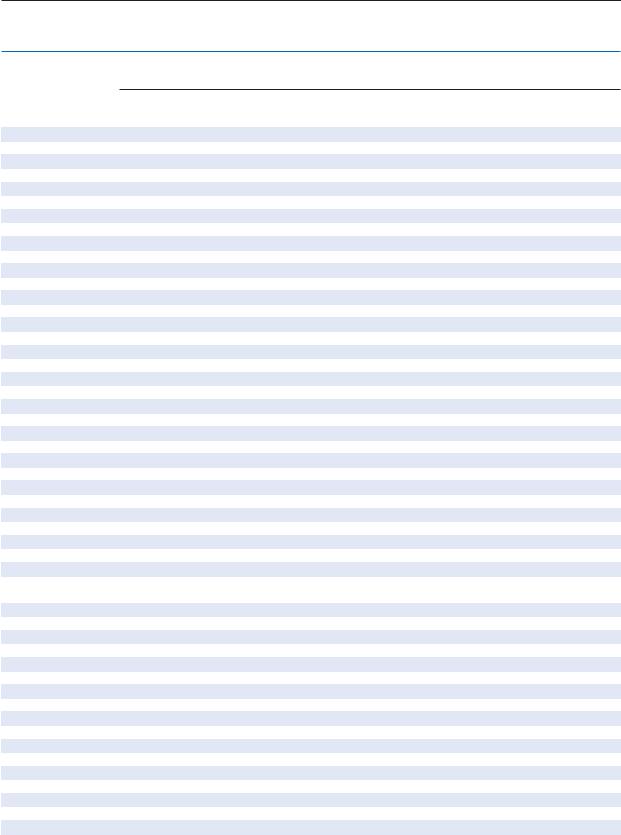

Table 6.3. Service demand volumes-for selected services

In-person inquiries (000s)

Written correspondence from taxpayers (000s) |

“Hits” on Internet webpage |

|

Paper |

(millions) |

|

Countries |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

662/1 |

542/1 |

3 110 |

5 006/1 |

19 |

19 |

2 256 |

3 014 |

Austria |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

126 |

133 |

32.4 |

58.7 |

Belgium |

n.a./1 |

n.a./1 |

n.a./1 |

n.a./1 |

n.a./1 |

n.a./1 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Canada |

240 |

234 |

410 |

360 |

/1 |

/1 |

82.3/1 |

88.2/1 |

Chile |

2 345 |

2 445 |

n.a. |

141 |

23 |

30 |

230 |

295 |

Czech Rep. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Denmark |

400 |

390 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

380 |

350 |

34.6 |

32.6 |

Estonia |

310 |

290 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

62.7 |

67.7 |

Finland |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

17 |

17 |

12.6 |

13.4 |

France |

15 150 |

17 860 |

>4 500 |

n.a. |

3 380 |

4 150 |

56.0 |

n.a. |

Germany |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Greece |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Hungary |

2 350 |

2 500 |

11 |

12 |

31 |

267 |

300.2 |

360.2 |

Iceland |

40 |

70 |

n.a |

61 |

12 |

18 |

7.7 |

12.0 |

Ireland |

870 |

810 |

2 890/1 |

2 720/1 |

In paper |

In paper |

16.4 |

18.2 |

Israel |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a |

Italy |

9 700 |

10 300 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

83 |

106 |

668.1 |

713.1 |

Japan |

4 200 |

3 760 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

117.3 |

125.5 |

Korea |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

298.7 |

298.8 |

Luxembourg |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

57.5 |

58.5 |

Mexico |

8 970 |

10 330 |

n.app. |

n.app. |

1 200 |

1 600 |

244.4 |

234.2 |

Netherlands |

880 |

980 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

0 |

0 |

43.0 |

71.6 |

New Zealand |

200 |

200 |

900 |

800 |

700 |

700 |

10.3 |

17.8 |

Norway |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

12.0 |

14.5 |

Poland |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Portugal |

14 988 |

12 976 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

111.3 |

123.9 |

Slovak Rep. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

<1 |

<1 |

6 |

6 |

n.a. |

n.a |

Slovenia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Spain |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

484.9 |

514.8 |

Sweden |

1 400 |

1 500 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

300 |

400 |

30.5 |

38.7 |

Switzerland |

0 |

0 |

200 |

200 |

100 |

100 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Turkey |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

1 |

3 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

United Kingdom |

3 090 |

3 200 |

11 390 |

9 690 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

United States |

6 380 |

6 390 |

20 790 |

19 830 |

52 |

53 |

307.5/1 |

322.5/1 |

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

333 |

344 |

131.3 |

155.0 |

Brazil |

20 300 |

20 100 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

120 |

145 |

76 |

107.3 |

Bulgaria |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

14 |

14 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

China |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Colombia |

3 270 |

3 140 |

1 450 |

920 |

116 |

98 |

5.29 |

5.4 |

Cyprus |

n.a. |

n.a. |

1 |

1 |

<1 (VAT) |

<1 (VAT) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Hong Kong, China |

230 |

210 |

430 |

440 |

100 |

110 |

22.13 |

24.8 |

India |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Latvia |

470 |

560 |

10 |

170 |

100 |

130 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Lithuania |

192 |

110/1 |

3 |

3 |

19 |

13 |

19.24 |

34.9 |

Malaysia |

81 |

93 |

8 |

4 |

120 |

96 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Malta |

46 |

44 |

19 |

20 |

1 |

2 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Romania |

n.a. |

n.a. |

3 |

47 |

13 |

17 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Russia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

172 |

160 |

17 |

50 |

30.46 |

37.27 |

Saudi Arabia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Singapore |

186 |

143 |

450 |

280 |

260 |

220 |

7.78 |

8.6 |

South Africa |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

8.1 |

8.6 |

For notes indicated by “/ (number)”, see Notes to Tables section at the end of the chapter, p. 228. Source: CIS survey responses.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

204 – 6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES

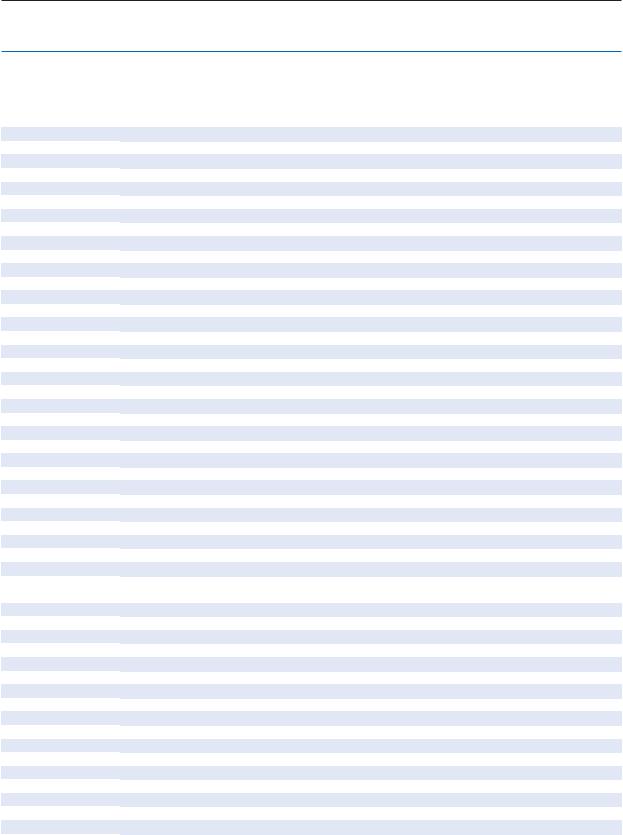

Table 6.4. Service demand volumes: Phone inquiries

|

|

|

Phone inquiries received (millions) |

|

|

Phone calls answered (excl. |

||

|

Handled by IVR/1 |

Other calls |

|

Total |

IVR-handled calls) (millions) |

|||

Country |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

1.09/2 |

1.78/2 |

10.12/2 |

10.98/2 |

11.21 |

12.77 |

8.89 |

9.35 |

Austria |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

n.a. |

3.54/2 |

n.a. |

3.54 |

n.a. |

3.54/2 |

Belgium |

|

|

1.006 |

1.255 |

1.006 |

1.255 |

0.704 |

0.628 |

Canada |

7.15 |

7.02 |

17.04 |

18.10 |

24.19 |

25.12 |

16.39 |

17.39 |

Chile |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.99 |

1.01 |

0.99 |

1.01 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

Czech Rep. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Denmark |

3.39 |

3.35 |

4.32 |

4.28 |

7.71 |

7.63 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Estonia |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.25 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.28 |

0.24 |

0.25 |

Finland |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

1.41 |

1.71 |

1.41 |

1.71 |

0.94 |

1.07 |

France |

n.a. |

n.a. |

3.14 |

4.34 |

3.14 |

4.34 |

3.25 |

3.07 |

Germany |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Greece |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Hungary |

1.26 |

1.23 |

0.814 |

0.774 |

2.07 |

2.00 |

0.78 |

0.75 |

Iceland |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.26 |

0.255 |

0.26 |

0.255 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

Ireland |

3.93 |

3.96 |

1.91 |

1.94 |

5.84 |

5.9 |

1.71 |

1.74 |

Israel |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a |

Italy |

0.08 |

0.09 |

2.61 |

3.63 |

2.69 |

3.72 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

Japan |

0.025 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

5.14 |

5.04 |

Korea |

5.01 |

4.78 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Luxembourg |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Mexico |

5.76 |

5.75 |

5.39 |

4.87 |

11.15 |

10.62 |

4.77 |

4.45 |

Netherlands |

n.a. |

n.a. |

15.09 |

15.81 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

13.73 |

14.02 |

New Zealand |

0.6 |

0.7 |

5.4 |

5.1 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

4.0 |

3.7 |

Norway |

n.a. |

n.a. |

2.62 |

2.66 |

2.62 |

2.66 |

2.18 |

1.99 |

Poland |

0.274 |

0.270 |

0.214 |

0.221 |

0.488 |

0.491 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Portugal |

1.13 |

1.16 |

n.a |

n.a |

1.13 |

1.16 |

0.71 |

0.98 |

Slovak Rep. |

n.appl. |

0.024 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Slovenia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Spain |

4.2 |

5.48 |

6.72 |

6.18 |

10.92 |

11.66 |

5.99 |

5.7 |

Sweden |

8.3 |

8.3 |

n.a |

n.a |

n.a. |

n.a. |

4.5 |

4.4 |

Switzerland/2 |

- |

- |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

Turkey |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.25 |

0.48 |

0.254 |

0.480 |

0.247 |

0.473 |

United Kingdom |

3.11 |

6.51 |

41.34 |

50.64 |

44.45 |

57.15 |

26.92 |

23.43 |

United States |

35.11 |

42.29 |

48.4/2 |

47.6/2 |

83.51 |

89.89 |

36.67 |

34.24 |

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

0.388 |

0.436 |

5.5 |

3.5 |

5.888 |

3.936 |

0.202 |

0.263 |

Brazil |

n.appl |

n.appl. |

10.16 |

9.71 |

10.16 |

9.71 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

Bulgaria |

0.125 |

0.095 |

0.218 |

0.211 |

0.343 |

0.306 |

0.207 |

0.2 |

China |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Colombia |

0.54 |

0.54 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Cyprus |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Hong Kong, China |

1.24 |

1.17 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

1.28 |

1.21 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

India |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Latvia |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

0.12 |

0.22 |

Lithuania |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.941 |

0.758 |

0.941 |

0.758 |

0.769 |

0.702 |

Malaysia |

0.072 |

0.091 |

0.426 |

0.466 |

0.420 |

0.438 |

0.492 |

0.528 |

Malta |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.183 |

0.145 |

0.183 |

0.145 |

0.102 |

0.068 |

Romania |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

0.98 |

1.0 |

0.98 |

1.0 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Russia |

n.a |

n.a |

n.a |

n.a |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a |

0.484 |

Saudi Arabia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Singapore |

0.542 |

0.467 |

1.066 |

1.047 |

1.608 |

1.514 |

0.997 |

0.996 |

South Africa |

n.appl. |

n.appl. |

5.66 |

6.16 |

5.66 |

6.16 |

5.04 |

5.58 |

For notes indicated by “/ (number)”, see Notes to Tables section at the end of the chapter, p. 228. Source: CIS survey responses.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

6. OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF REVENUE BODIES – 205

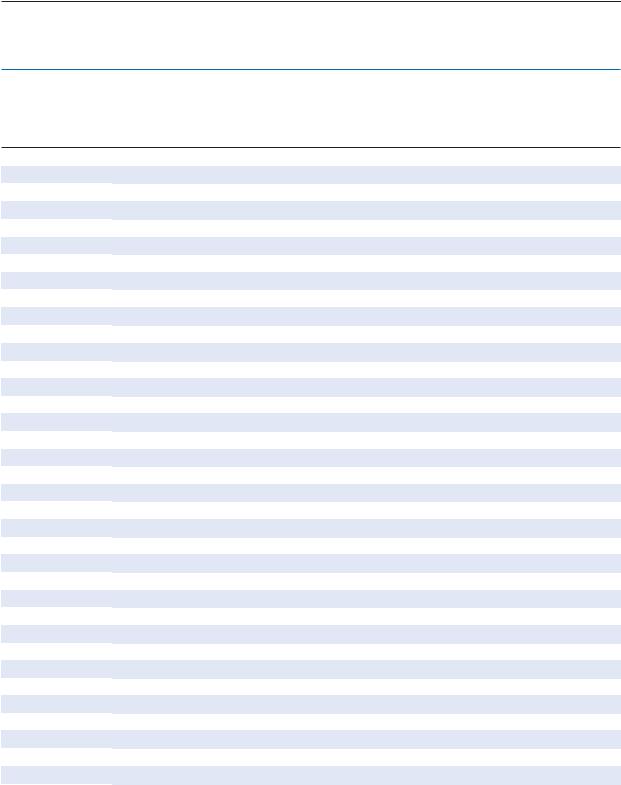

Table 6.5. Taxpayer services: Selected administrative features and demand ratios

(This table only includes revenue bodies that reported volumes of in-person and phone inquiries answered)

|

2010 citizen |

|

population |

Country |

(mln) |

|

|

|

|

|

Phone inquiries answered |

|

|

|

|

In-person inquiries: |

(excl. IVR handled): |

||

Selected features of administration |

No. per 100 citizens |

No. per 100 citizens |

||||

Non-tax |

|

In-person |

|

|

|

|

roles/1 |

Local offices |

payments |

2010 |

2011 |

2010 |

2011 |

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

22.3 |

R |

11 |

|

2.95 |

2.42 |

39.9 |

41.9 |

Austria |

8.4 |

|

40 |

1.5% |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

42.2 |

Belgium |

10.8 |

|

1 182 |

9 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

6.5 |

5.8 |

Canada |

34.1 |

W |

40 |

5% |

0.7 |

0.7 |

48.1 |

51.0 |

Chile |

17.1 |

|

46 |

|

13.7 |

14.2 |

4.9 |

4.9 |

Denmark |

5.5 |

C |

28 |

|

7.3 |

7.1 |

n.a |

n.a |

Estonia |

1.3 |

C |

- |

1% |

23.8 |

22.3 |

18.5 |

19.2 |

Finland |

5.4 |

|

43 |

|

n.a. |

n.a. |

17.4 |

19.8 |

France |

62.6 |

|

1 500 |

9 |

24.2 |

28.5 |

5.2 |

4.9 |

Hungary |

10.0 |

C |

52 |

|

23.5 |

25.0 |

7.8 |

7.5 |

Iceland |

0.3 |

|

- |

9 |

13.3 |

23.3 |

43 |

43 |

Ireland |

4.5 |

C |

74 |

|

19.3 |

18.0 |

38.1 |

38.6 |

Italy |

60.2 |

|

108 |

|

16.1 |

17.1 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

Japan |

127.5 |

|

524 |

4.2% |

3.3 |

2.9 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

Mexico |

108.4 |

C |

67 |

|

8.3 |

9.5 |

4.4 |

4.1 |

Netherlands |

16.5 |

C, W |

- |

|

5.3 |

5.9 |

83.2 |

85 |

New Zealand |

4.4 |

R, W |

17 |

|

4.5 |

4.5 |

90.9 |

84.1 |

Norway |

4.9 |

|

200/1 |

|

n.a. |

n.a. |

44.5 |

40.6 |

Portugal |

10.6 |

|

343 |

47.1% |

141 |

122.6 |

6.7 |

9.2 |

Spain |

46.1 |

C |

202/1 |

|

n.a. |

n.a. |

13.0 |

12.4 |

Sweden |

9.4 |

|

- |

|

14.9 |

16.0 |

47.8 |

46.8 |

Switzerland |

7.8 |

|

- |

|

n.a. |

n.a. |

25.6 |

25.6 |

Turkey |

72.7 |

|

1063 |

9 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

0.4 |

0.7 |

United Kingdom |

61.3 |

|

224 |

|

5.0 |

5.2 |

43.9 |

38.2 |

United States |

309.1 |

|

134 |

0.5% |

2.1 |

2.1 |

11.9 |

11.1 |

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

42.2 |

C |

|

|

n.a. |

n.a. |

<1 |

<1 |

Brazil |

195.0 |

C |

|

|

10.4 |

10.3 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

Colombia |

45.2 |

C |

- |

|

7.2 |

6.9 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Hong Kong, China |

7.2 |

|

- |

0 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

< 1 |

< 1 |

Latvia |

2.1 |

C |

34 |

|

22.4 |

26.6 |

5.7 |

10.5 |

Lithuania |

3.4 |

|

- |

|

5.6 |

3.2 |

22.6 |

20.6 |

Malaysia |

29.2 |

|

|

9 |

< 1 |

< 1 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

Malta |

0.4 |

|

- |

5% |

11.5 |

11.0 |

25.5 |

17 |

Singapore/2 |

5.2 |

|

0 |

|

3.6 |

2.8 |

19.2 |

19.1 |

South Africa |

50.1 |

C |

35 |

9 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

10.1 |

11.1 |

/1. C: customs administration; R: retirement incomes/superannuation; and W: welfare benefits, etc.

/2. Number indicated is % of total payments; 9 indicates that local offices collect tax payments but volumes are not known. Singapore: Citizen population includes Singapore citizens, permanent residents and foreigners.

Sources: CIS survey responses, population data from OECD Factbook 2011 and CIA World Factbook.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013