- •Table of contents

- •Abbreviations and Acronyms

- •Executive summary

- •Introduction

- •Institutional arrangements for tax administration

- •Key points

- •Introduction

- •The revenue body as an institution

- •The extent of revenue body autonomy

- •Scope of responsibilities of the revenue body

- •Special governance arrangements

- •Special institutional arrangements for dealing with taxpayers’ complaints

- •Bibliography

- •The organisation of revenue bodies

- •Getting organised to collect taxes

- •Office networks for tax administration

- •Large taxpayer operations

- •Managing the tax affairs of high net worth individuals taxpayers

- •Bibliography

- •Selected aspects of strategic management

- •Key points and observations

- •Managing for improved performance

- •Reporting revenue body performance

- •Summary observations

- •Managing and improving taxpayers’ compliance

- •Bibliography

- •Human resource management and tax administration

- •Key points

- •Aspects of HRM Strategy

- •Changes in policy in aspects of HRM within revenue bodies

- •Staff metrics: Staff numbers and attrition, age profiles and qualifications

- •Resources of national revenue bodies

- •Key points and observations

- •The resources of national revenue bodies

- •Impacts of recent Government decisions on revenue bodies’ budgets

- •Overall tax administration expenditure

- •Measures of relative costs of administration

- •International comparisons of administrative expenditure and staffing

- •Bibliography

- •Operational performance of revenue bodies

- •Key points and observations

- •Tax revenue collections

- •Refunds of taxes

- •Taxpayer service delivery

- •Are you being served? Revenue bodies’ use of service delivery standards

- •Tax verification activities

- •Tax disputes

- •Tax debts and their collection

- •Bibliography

- •The use of electronic services in tax administration

- •Key points

- •Provision and use of modern electronic services

- •Bibliography

- •Tax administration and tax intermediaries

- •Introduction

- •The population and work volumes of tax intermediaries

- •Regulation of tax intermediaries

- •The services and support provided to tax intermediaries

- •Bibliography

- •Legislated administrative frameworks for tax administration

- •Key findings and observations

- •Introduction

- •Taxpayers’ rights and charters

- •Access to tax rulings

- •Taxpayer registration

- •Collection and assessment of taxes

- •Administrative review

- •Enforced collection of unpaid taxes

- •Information and access powers

- •Tax offences (including policies for voluntary disclosures)

- •Bibliography

182 – 5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES

Very high ratios (i.e. greater than 0.300%) are consistently displayed for three revenue bodies (i.e. Belgium, Hungary and the Netherlands).

A consistent downwards trend in relative administrative costs can be observed for a small number of countries (e.g. Australia, Denmark, France, Lithuania, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Russia and United Kingdom).

Within-country comparisons of this ratio over time may be suitable for drawing assessments of relative efficiency over time, although the indicator is susceptible to regular revisions of GDP made by the respective government bodies.

As for the cost of collection ratio already discussed, cross-country comparisons of this ratio in the context of assessments of relative efficiency need to be undertaken with considerable care to avoid ill-founded conclusions.

International comparisons of administrative expenditure and staffing

Cost of collection ratios

Given the many similarities in the taxes administered by federal revenue bodies from country to country, there has been a natural tendency by observers to make cross-country comparisons of “cost of collection” ratios and draw conclusions on revenue body efficiency and effectiveness. However, experience shows that such comparisons are difficult to carry out in a consistent fashion given a range of variables to be taken into account – see Box 5.2. The most significant factors to be taken account of that are not related to efficiency and effectiveness are: 1) variations in the size of the legislated tax burden; and 2) the range and nature of taxes administered, in particular whether the revenue body is responsible for the collection of social security contributions.

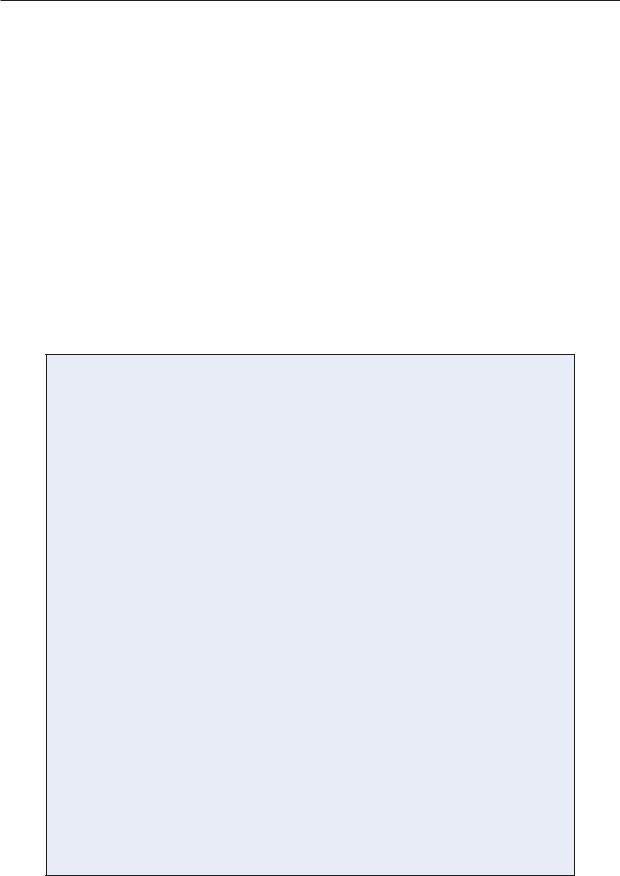

Many of the factors referred to are evident from the data in Table 5.3. For example:

For many surveyed countries (particularly a number in Europe) social security contributions, which in many countries constitute a significant revenue stream, are collected by a separate agency and therefore their costs and the revenue collected are excluded from the calculation used to compute the ratio – see information below which illustrates this particular aspect):

|

|

Countries (by level of tax/GDP in 2011) * |

|

Cost of collection ratio in 2011 |

20-30% |

30-40% |

Over 40% |

|

|

|

|

Less than 0.60 |

|

Estonia |

Norway, Sweden |

0.61 -0.80 |

United States |

Iceland |

Austria,* Denmark, Finland |

0.81-1.00 |

Korea,* United Kingdom |

Netherlands, Luxembourg,* |

|

|

|

Slovenia, Spain* |

|

1.01-1.20 |

|

Hungary, Ireland, |

France* |

1.21-1.40 |

|

Portugal* |

Czech. Rep.,* Germany* |

Over 1.41 |

Japan* |

Poland,* Slovak Rep.* |

Belgium* |

|

|

|

|

* For these countries, SSC are collected by separate agencies, not the revenue body.

The inability of some revenue bodies (i.e. Ireland, Mexico (prior to 2005), South Africa and Spain) to exclude the costs of non-tax functions (e.g. customs, welfarerelated roles) from the cost base used to calculate the ratio;

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES – 183

There are substantial differences in the statutory tax burden (and hence the potential tax revenue base) across surveyed countries (ranging from below 20% to almost 50% of GDP) that influences what is collected in practice, and hence the computed ratio; and

Unusual institutional arrangements exist in some countries (e.g. Italy for tax fraud functions, Chile and Sweden for tax debt collection functions) that see some mainstream tax administration-related functions performed by a body separate from the main revenue body; as a result, the cost data used to compute the ratio for these bodies understates the real costs of tax administration, and hence the computed ratio.

For these sorts of reasons, international comparisons of both these ratios need to be made with considerable care and take account of any abnormal factors highlighted, as well as other differences in approaches to tax administration highlighted elsewhere in this series.

Box 5.2. International comparisons of cost of collection ratios

Analytical work undertaken in conducting comparisons of cost of collection ratios has revealed that there are many factors to explain the marked variations in the ratio observed from country to country. The more significant factors are described below:

Differences in tax rates and structure: Rates of tax and the actual structure of taxes all will have a bearing on aggregate revenue and, to a lesser extent, cost considerations. For example, comparisons of the ratio involving high-taxing countries (e.g. those where tax burdens regularly exceed 40% of GDP) and low-taxing countries (e.g. those where tax burdens are less than 20%) are hardly realistic given their widely varying tax burdens.

Differences in the range and nature of taxes administered by federal revenue authorities: There are a number of differences that can arise here. In some countries, more than one major tax authority may operate at the national level (e.g. as in India, Cyprus and Malta), or taxes at the federal level are predominantly of a direct tax nature, while indirect taxes are administered largely by separate regional/state authorities (e.g. the United States). In other countries, one national authority will collect taxes for all levels of government, i.e. federal, regional and local governments (a number of EU countries).

Collection of social insurance contributions, etc.: As described earlier in this series, there are significant variations from country to country in the collection of social security contributions. A few countries (e.g. Australia, New Zealand) do not have separate regimes of mandatory social contributions, while others make separate provision for them and have them collected by the main tax revenue collection agency. Some countries have them collected by a separate government agency. Given that social contributions are a major source of tax revenue for many countries, the inclusion/exclusion of social contributions in the revenue base for “cost of collection” calculation purposes can have a significant bearing on the computed ratio.

Differences in the range of functions undertaken: The range of functions undertaken by revenue bodies can vary from country to country. For example, in some countries the revenue body is also responsible for carrying out activities not directly related to tax administration (e.g. administration of customs laws, the administration of certain welfare benefits), while in others some tax-related functions are not carried out by the revenue body (e.g. enforced debt collection). Ideally, these sorts of differences should be allowed for in any cross-country comparisons undertaken of relative aggregate costs and related ratios.

Lack of a common measurement methodology: There is no universally accepted methodology for the measurement of administrative costs. Revenue bodies that publish a cost of collection ratio generally do not reveal precise details of the measurement approach adopted for their calculations. In relation to administrative costs, the treatment of employee pension costs, accommodation costs, interest paid on overpaid taxes, the use of cash and noncash methods (e.g. by means of a float) to recompense financial institutions for collecting tax payments, and capital equipment purchases are some of the potentially significant areas where the measurement approaches adopted may vary. The ratio is also influenced by the selection of the revenue base i.e. “gross” or “net” (i.e. after refunds) revenue collections figure for its computation. For example, the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which has one of the lowest reported cost of collection ratios for any national revenue body, and the Irish Office of the Revenue Commissioners, both use “gross” revenue as the basis of their reported computation, while most other authorities use a “net” figure. As a result, for both countries the reported ratio is around 10-12 % lower than if it were computed on a “net” revenue basis. (NB: For this series, calculations are made on the basis of “net revenue” collections.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

184 – 5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES

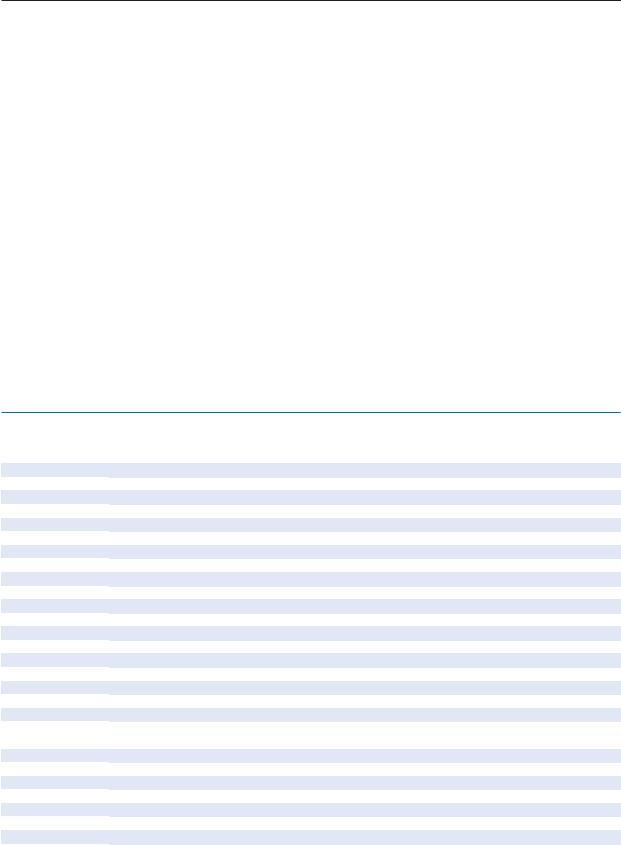

Relative staffing levels of revenue bodies

A summary of the staff usage (expressed as FTEs) by national revenue bodies is set out in Table 5.5. To the extent possible and to allow cross-country comparisons, efforts have been made to exclude staffing related non-tax related roles. In order to reflect a degree of relativity, aggregate staff levels have been compared with overall official country population and labor force data to compute two ratios: 1) the number of citizens per one full-time staff member: and 2) the number of labor force participants per full-time staff member.

Comparisons of this nature are naturally subject to some of the qualifications referred to concerning “cost of collection” ratios – in addition to efficiency considerations, exogenous factors such as the range of taxes administered (e.g. social contributions, motor vehicle and property taxes) and the performance of non-tax related roles (where these cannot be isolated) all impact on the magnitude of the reported ratio. For some countries, demographic features (e.g. country age profile and rate of unemployment) are also likely to be relevant. Revenue bodies in a number of countries (e.g. UK) also have major restructuring programmes underway, some of which project significant planned staffing reductions over the coming years. To assist readers, known abnormal factors influencing the reported ratios have been identified.

Concerning OECD countries, it will be evident that the greatest level of consistency occurs in relation to the ratio based on country labour forces (i.e. the number of labour force participants/one revenue body staff member (FTE)):

Seven revenue bodies have a ratio less than 400 (for some, including customs work);

Twelve revenue bodies have a ratio between 401-600;Seven are between 601-800; and

Eight revenue bodies have a ratio over 800 (with six “outliers” (i.e. Chile, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Switzerland and the United States) where the ratio exceeds 1 000).

For Chile (1 943:1), the staffing data provided do not cover the full range of normal tax administration functions and as a result the respective ratios are not directly comparable with others (although probably not to a significant degree). In the case of Japan, where the ratio is 1 113:1, staffing levels of the revenue body (i.e. the NTA) have remained in the region of 50 000 to 56 000 for the last 50 years, reflecting decisions both to keep staff resources roughly constant and, importantly, to minimise workloads. Compared to other countries, administrative workloads have been kept relatively low with the assistance of, among other things; special tax system design features (e.g. high thresholds for various reporting and payment obligations, less frequent tax payment obligations and extensive use of tax withholding). (Further information on some of these features can be found in Chapter 9.) Also relevant is the collection of social security contributions by a separate agency. Korea (with a ratio of 1 383:1) also makes extensive use of tax system design features that minimise workloads, in comparison with arrangements seen in other countries. For example, there is substantial use of final withholding systems for the bulk of employee taxpayers (employers withhold monthly, calculate employees’ tax liability and clear the balance off at the end of year), withholding at source arrangements for dividend and interest income and certain payments for independent services, and biannual reporting and payment arrangements for VAT liabilities.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES – 185

Table 5.5. Revenue body staff usage for fiscal year 2011 and related ratios/1

|

Staff usage aggregates (FTEs) |

|

Staff usage ratios |

||||

|

|

|

|

Citizens/ |

Labour force/ |

|

|

|

|

Tax and |

% FTEs for tax |

FTEs on tax |

FTEs on tax |

Factors affecting comparability |

|

|

All revenue body |

related support |

and support |

and support |

and support |

of countries’ computed ratios |

|

Country |

functions |

functions) |

functions |

functions |

functions |

(i.e. ratios in columns 5 and 6) |

|

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

21 764 |

18 169 |

83.5 |

1 245 |

663 |

|

|

Austria |

7 728 |

7 690 |

99.5 |

1 095 |

561 |

|

|

Belgium |

10 488 |

10 472 |

99.8 |

1 040 |

464 |

|

|

Canada |

40 173 |

38 722 |

96.4 |

881 |

483 |

|

|

Chile |

4 169 |

4 169 |

100.0 |

4 137 |

1 943 |

FTEs exclude debt collection |

|

Czech Rep. |

14 640 |

13 944 |

95.2 |

753 |

376 |

|

|

Denmark |

7 589 |

6 871 |

90 5 |

810 |

413 |

|

|

Estonia |

1 787 |

783 |

43.8 |

1 711 |

889 |

|

|

Finland |

5 229 |

5 229 |

100.0 |

1 030 |

511 |

|

|

France |

117 657 |

69 650 |

59.2 |

942 |

409 |

|

|

Germany |

110 515 |

110 515 |

100.0 |

740 |

381 |

|

|

Greece |

9 300 |

9 300 |

100.0 |

1 216 |

534 |

|

|

Hungary |

23 059 |

16 976 |

73.6 |

589 |

251 |

|

|

Iceland |

257 |

257 |

100.0 |

1 241 |

700 |

|

|

Ireland |

5 962 |

5 962 |

100.0 |

752 |

355 |

FTEs include customs |

|

Israel |

5 566 |

5 566 |

100.0 |

1 393 |

627 |

|

|

Italy/2 |

32 619 |

32 619 |

100.0 |

1 849 |

767 |

|

|

Japan |

56 261 |

56 261 |

100.0 |

2 272 |

1 113 |

|

|

Korea |

19 671 |

18 145 |

92.2 |

2 743 |

1 383 |

|

|

Luxembourg |

914 |

891 |

97.5 |

574 |

432 |

|

|

Mexico |

35 718 |

25 009 |

70.0 |

4 492 |

1 944 |

|

|

Netherlands |

29 410 |

23 014 |

78.3 |

722 |

381 |

|

|

New Zealand |

5 513 |

3 789 |

68.7 |

1 163 |

625 |

|

|

Norway |

5 947 |

5 947 |

100.0 |

833 |

440 |

|

|

Poland |

48 634 |

48 305 |

99.3 |

791 |

370 |

|

|

Portugal |

10 073 |

10 073 |

100.0 |

1 048 |

547 |

|

|

Slovak Rep. |

5 343 |

5 173 |

96.8 |

1 050 |

526 |

|

|

Slovenia |

2 417 |

2 417 |

100.0 |

847 |

387 |

|

|

Spain |

27 613 |

23 556 |

85.3 |

1 958 |

976 |

|

|

Sweden |

9 584 |

8 205 |

85.6 |

1 152 |

612 |

FTEs exclude debt collection |

|

Switzerland |

985 |

940 |

95.4 |

8 324 |

5 211 |

Data for VAT administration |

|

only |

|||||||

Turkey |

40 298 |

40 268 |

99.9 |

1 836 |

664 |

||

|

|||||||

United Kingdom |

66 466 |

66 466 |

100.0 |

929 |

474 |

|

|

United States |

94 709 |

94 709 |

100.0 |

3 290 |

1 622 |

No major indirect tax |

|

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

22 832 |

17 596 |

77.1 |

2 398 |

952 |

FTEs include customs |

|

Brazil |

25 840 |

25 840 |

100.0 |

7 714 |

4 052 |

||

Bulgaria |

7 708 |

7 703 |

99.9 |

914 |

320 |

|

|

China |

755 000 |

755 000 |

100.0 |

1 779 |

1 054 |

|

|

Colombia |

8 543 |

4 659 |

54.5 |

9 710 |

4 819 |

|

|

Cyprus |

888 |

878 |

98.9 |

957 |

490 |

|

|

Hong Kong, China |

2 818 |

2 574 |

91.3 |

2 779 |

1 439 |

Data for direct taxes only |

|

India |

40 756 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

||

Indonesia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

|

Latvia |

4 145 |

2 860 |

69.0 |

766 |

409 |

|

|

Lithuania |

3 516 |

3 516 |

100.0 |

1 003 |

462 |

Data for direct taxes only |

|

Malaysia |

10 209 |

10 209 |

100.0 |

2 858 |

1 167 |

||

Malta |

781 |

770 |

98.6 |

532 |

221 |

|

|

Romania |

27 016 |

24 009 |

88.9 |

909 |

385 |

|

|

Russia |

146 089 |

141 806 |

97.1 |

1 005 |

532 |

Very limited range of taxes |

|

Saudi Arabia |

1 386 |

1 386 |

100.0 |

19 145 |

5 505 |

||

Singapore/2 |

1 851 |

1 851 |

100.0 |

2 892 |

1 767 |

|

|

South Africa |

14 944 |

13 594 |

91.0 |

3 591 |

1 299 |

|

|

For notes indicated by “/ (number)”, see Notes to Tables section at the end of the chapter, p. 192. Source: CIS survey responses, OECD Statistics Database and CIA Factbook.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

186 – 5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES

With annual tax collections equivalent to around 20% of GDP, Mexico’s tax system (ratio of 1 944:1) is of a considerably smaller scale than most other OECD countries. Its tax system arrangements are characterised by substantial use of final withholding system arrangements for employee taxpayers (with quite limited registration of personal taxpayers (equivalent to around to 20 % of the official labor force)), and a relatively small population of registered business taxpayers. The very high ratio for Switzerland (i.e. 5 211:1) results from the fact that the Federal Tax Administration is responsible only for VAT administration, with both personal and corporate income taxes administered at the subnational level by separate agencies in each canton. For this reason, the ratio largely reflects the resources required for VAT administration, thus making it incomparable with all other national revenue bodies.

In the case of the United States (where the ratio is 1 622:1), a meaningful comparison of relative staffing levels with other surveyed countries is complicated by the absence of a national VAT (or a similar tax), as is the case in all other OECD countries. A further consideration is that, unlike most other surveyed countries, there are separate income taxes and retail sales taxes levied at the state level in the United States that are administered separately by state revenue agencies, not by the IRS. (A more appropriate comparison would necessitate account being taken of the staff required by these agencies, which is beyond the scope of what is feasible for CIS purposes.) For these reasons, the computed ratio for the IRS – and this observation applies also to its computed “cost of collection” ratio – is not really comparable with that of revenue bodies in any other OECD country.

For revenue bodies in non-OECD surveyed countries, the computed ratio reflects an even greater divergent pattern, ranging from 221:1 to over 5 000:1. The full range of factors that might explain this disparity has not been identified.

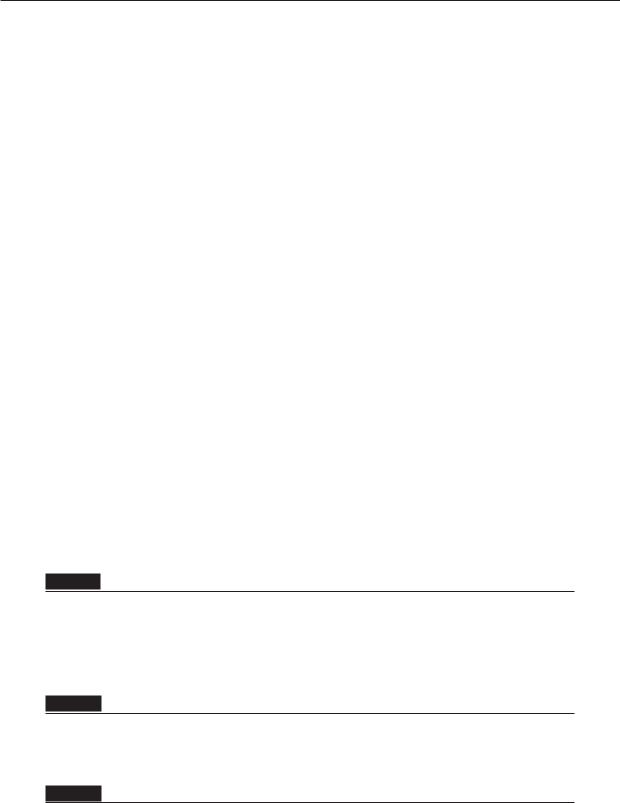

Allocation of staff resources by functional groupings

Given the similarity in the taxes administered across most surveyed countries, an important issue concerns how resources are allocated across broad functional groupings. Table 5.6 provides an indication of country practices for just under 90% of revenue bodies concerning the allocation of resources in 2011 to compliance functions (i.e. audit and related verification functions, and enforced debt collection) and other key functional groupings.

Given definitional issues (e.g. what constitutes “verification” work), and the possibility of some inconsistencies in the compilation of data, this information needs to be interpreted with care.5 Nevertheless, it does indicate that there are potentially substantial differences in staff allocation policies and practices, which may warrant further inquiry. For example:

Client account management functions: Significantly for this grouping, just over one third of revenue bodies (17) reported staff usage exceeding 30% of aggregate staff; of these revenue bodies, 12 reported IT expenditure less than 10% of total expenditure (or were unable to quantify the amount of IT expenditure incurred).

Audit, investigation and other verification activities: Survey responses for this category varied significantly ranging from around 9 to almost 70%. Around 40% of surveyed revenue bodies reported usage in excess of 30%, including five with over 50% allocated to this functional activity (i.e. Austria, Iceland, Japan, Netherlands, and Singapore).

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES – 187

Table 5.6. Staff usage (2011) by major tax functional groupings (% of total usage)

|

|

|

Total staff usage on major tax functions as a share of total usage/1 |

|

|||

|

Total FTEs for |

|

|

|

|

Support: |

|

|

all tax functions |

Account |

|

Tax debt |

Other tax |

human |

Support: other |

Country |

and support) |

management |

Verification |

collection |

operations |

resource |

functions |

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

18 169 |

20.4 |

34.0 |

10.7 |

15.5 |

6.2 |

13.1 |

Austria |

7 690 |

11.9 |

69.8 |

10.5 |

1.7 |

6.0 |

0.0 |

Belgium |

10 472 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Canada |

38 722 |

28.3 |

26.2 |

19.2 |

6.7 |

3.9 |

15.7 |

Chile |

4 169 |

20.0 |

39.0 |

0.0 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

36.3 |

Czech Rep. |

13 944 |

59.3 |

20.3 |

6.0 |

14.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Denmark |

6 871 |

25.2 |

37.9 |

14.5 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

17.8 |

Estonia |

783 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Finland |

5 229 |

36.5 |

40.7 |

9.6 |

3.5 |

2.0 |

7.8 |

France |

69 650 |

43.8 |

14.9 |

10.8 |

11.6 |

-------------- 18.9 ------------- |

|

Germany |

110 515 |

40.3 |

30.2 |

9.9 |

11.2 |

8.4 |

0.0 |

Greece |

9 300 |

n.a. |

--------------- 18.7 -------------- |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Hungary |

16 976 |

25.7 |

32.0 |

16.3 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

23.3 |

Iceland |

257 |

13.2 |

63.0 |

0.0 |

7.4 |

0.8 |

15.6 |

Ireland/2 |

5 962 |

29.6 |

28.2 |

12.3 |

8.8 |

1.8 |

19.3 |

Israel |

5 566 |

12.6 |

33.8 |

14.4 |

32.3 |

0.5 |

6.4 |

Italy/2 |

32 619 |

34.5 |

48.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

5.2 |

12.1 |

Japan/2 |

56 261 |

0.0 |

63.1 |

21.2 |

2.3 |

0.7 |

12.7 |

Korea/2 |

18 145 |

63.5 |

22.2 |

4.7 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

7.6 |

Luxembourg |

891 |

51.2 |

11.4 |

19.2 |

11.4 |

3.2 |

3.6 |

Mexico |

25 009 |

15.5 |

35.2 |

23.9 |

8.0 |

2.9 |

14.5 |

Netherlands |

23 014 |

29.4 |

30.9 |

6.8 |

10.8 |

1.4 |

20.7 |

New Zealand |

3 789 |

42.6 |

19.6 |

8.1 |

15.2 |

1.8 |

12.8 |

Norway |

5 947 |

36.1 |

22.2 |

5.1 |

16.4 |

20.3 |

0.0 |

Poland |

48 305 |

17.0 |

27.0 |

11.9 |

19.3 |

1.6 |

23.2 |

Portugal |

10 073 |

52.0 |

17.7 |

21.7 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

7.3 |

Slovak Rep. |

5 173 |

42.9 |

30.9 |

6.2 |

8.3 |

1.4 |

10.3 |

Slovenia |

2 417 |

41.7 |

14.2 |

10.8 |

24.9 |

0.0 |

8.2 |

Spain |

23 556 |

31.4 |

22.4 |

19.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

26.5 |

Sweden/2 |

8 205 |

0.0 |

29.6 |

2.7 |

11.7 |

0.0 |

56.0/3 |

Switzerland |

940 |

9.0 |

26.1 |

7.4 |

41.5 |

13.8 |

2.1 |

Turkey |

40 268 |

75.4 |

0.0 |

10.8 |

0.0 |

4.3 |

9.5 |

United Kingdom |

66 466 |

40.4 |

33.9 |

9.8 |

8.0 |

1.7 |

6.2 |

United States |

94 709 |

31.9 |

16.4 |

33.0 |

2.8 |

1.8 |

14.1 |

OECD ave. (unw.) |

|

31.7 |

30.4 |

11.5 |

9.4 |

3.3 |

13.7 |

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

17 596 |

19.2 |

35.6 |

7.0 |

12.7 |

2.2 |

23.3 |

Brazil/2 |

25 840 |

16.3 |

16.9 |

21.8 |

7.6 |

2.0 |

35.4 |

Bulgaria |

7 703 |

25.5 |

41.9 |

9.5 |

13.3 |

1.1 |

8.8 |

China |

755 000 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Colombia |

4 659 |

13.1 |

23.9 |

27.3 |

11.0 |

2.9 |

21.8 |

Cyprus |

878 |

20.5 |

37.0 |

11.5 |

17.8 |

0.9 |

12.3 |

Hong Kong, China |

2 574 |

59.4 |

9.3 |

16.9 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

12.2 |

India |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Indonesia |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Latvia |

2 860 |

39.3 |

23.0 |

8.9 |

14.7 |

1.3 |

12.8 |

Lithuania |

3 516 |

38.7 |

28.7 |

6.8 |

14.1 |

1.0 |

10.7 |

Malaysia |

10 209 |

8.0 |

23.3 |

15.9 |

29.9 |

1.8 |

21.3 |

Malta |

770 |

16.2 |

18.4 |

4.3 |

50.8 |

1.9 |

8.3 |

Romania |

24 009 |

22.1 |

22.9 |

13.9 |

15.1 |

1.3 |

24.8 |

Russia |

141 806 |

16.3 |

41.5 |

8.6 |

9.2 |

1.9 |

22.4 |

Saudi Arabia |

1 386 |

11.8 |

36.2 |

11.0 |

6.9 |

31.5 |

2.5 |

Singapore/2 |

1 851 |

8.8 |

51.8 |

11.3 |

10.5 |

1.7 |

15.9 |

South Africa |

13 594 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

For notes indicated by “/ (number)”, see Notes to Tables section at the end of the chapter, p. 192. Source: CIS survey responses & Secretariat research (e.g. revenue body reports).

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

188 – 5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES

Enforced debt collection and related functions: Usage for this functional grouping ranged from a low 2% (in Sweden where this work is primarily the responsibility of a separate body) to almost 34% (in the United States); significantly, over half of surveyed bodies disclosed total usage exceeding 10% of aggregate staff, and in 12 countries the proportion exceeded 15% indicating the relative importance of this function in these offices; of the 12 countries devoting over 15% of aggregate resources to enforced debt collection, it is noteworthy that 8 reported a relative decline in debt levels for 2011, two reported a stable position, and an increase was reported by only one revenue body. Generally speaking, revenue bodies in OECD countries devote a substantially greater proportion of their resources to this area of tax administration.

Corporate overhead functions (including IT support and human resources): Usage for this functional grouping also varied enormously, suggesting some inconsistency in how these functions are viewed and quantified. Against an average across OECD countries of around 17%, seven revenue bodies (i.e. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Romania, Saudi Arabia, and Spain) reported an abnormally high proportion (i.e. over 25%) of total staffing (the precise reasons for which have not been identified).

There are many factors that may explain some of the abovementioned variations in functional staff resource allocations between revenue bodies, including (1) the use of administrative assessment versus self-assessment for income tax; (2) the degree of automation of routine tax administration tasks; (3) the degree to which some functions are centralised and therefore may require less staff (e.g. data processing and contact centres); (4) the extent of reliance on outsourcing (e.g. for IT support), which is discussed briefly in the following section;

(5) the extent of staff devoted to overheads; (6) the nature and size of a revenue bodies’ network of offices; and (7) misclassification of underlying resource usage data. The widely fluctuating data points to the need for care in the conduct of detailed cross-country benchmarking exercises.

Outsourcing of revenue body functions/operations

Outsourcing is a growing phenomenon in the private sector and is being increasingly used by government agencies, including some revenue bodies, as a means of carrying out tasks and functions in a more cost effectiveness manner. Outsourcing the provision of IT infrastructure is fairly common among OECD revenue bodies (e.g. Australia, New Zealand, and UK) and indeed, in some countries, the Government has decreed the use of outsourcing for IT infrastructure provision as their preferred approach. For this series, revenue bodies were asked to identify whether specific tax administration functions were outsourced (beyond IT operations) – see below:

Nature of work outsourced |

Revenue bodies using outsourcing for this work |

|

|

Collect and process tax payments |

Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Finland, Greece, Hong |

(e.g. via bank/post office) |

Kong, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Malaysia, Malta, |

|

Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovak Rep., South Africa, Spain, |

|

Sweden, Turkey, United States |

Answering taxpayer inquiries |

Australia, Belgium, Brazil, China, Colombia, Greece, India, Mexico, New Zealand (peak periods |

(e.g. call centre operations) |

only), Russia (to a Federal public service body), Spain (basic inquiries only), United States |

Data processing operations |

Brazil, Germany (some regions only), Greece, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, |

|

Mexico, Sweden |

Enforced collection of tax debts |

Australia, Ireland, Italy, Singapore (use of private law firm to initiate civil legal proceedings |

|

(against delinquent taxpayers for not paying tax debts. private liquidators are appointed |

|

to manage cases for winding-up) and United Kingdom (limited to debts that cannot be |

|

collected internally) |

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES – 189

The use of outsourcing arrangements for debt collection activities is a contentious issue and although not practised widely there is one revenue body that can point to a fair deal of success. Box 5.3 sets out largely verbatim comments from a recent government external audit report that describes the experiences of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) with its use of external collection agents. With many revenue bodies under pressure to reduce costs and improve performance, including reduction in their debt inventories (see Chapter 6), the audit’s findings may be of interest.

With many revenue bodies required to reduce their costs in the coming years it is likely that use of outsourcing and/or the provision of services on a jointly-shared basis across a number of Government agencies will increase over the medium term. Concerning this latter approach, two revenue bodies (i.e. New Zealand and the UK) reported for this series that their Governments were either studying or piloting the provision of some administrative support services (e.g. human resource management, facilities management) on a “whole of Government”/ multi-agency basis. Similarly, as noted in Chapter 2, the Canadian federal government has recently created a new department – Shared Services Canada – with a mandate to lower costs and improve services by consolidating and streamlining government IT networks, data centres, and email systems; resources related to these services were transferred from some 43 federal departments and agencies to create the department, including from the CRA which transferred some 750 FTEs.

Box 5.3. Australia: Experience with the use of external collection agents

The verbatim comments hereunder were extracted from a recent report of the Australian National Audit Office concerning the ATO’s use of external collection agents.

The referral of collectable debt to external collection agents (ECAs) was trialled through a pilot program in April 2006, and subsequently fully implemented by the ATO through the establishment of contracts with four ECAs in October 2007. It was one of several new measures to contain and reduce the amount of outstanding collectable debt, which had increased yearly since 2001-02, with the annual rate of increase peaking in 2004-05 at almost 28%. Individually the debt cases referred to ECAs are low in value and unlikely to be actioned by the ATO, but collectively represent significant revenue.

The ATO is now in the fifth year of referring lower value, non-complex income tax, activity statement and superannuation guarantee charge debt cases to ECAs for collection action, employing a correspondence and telephone-based approach. The initiative provides the ATO with a flexible mechanism to action a workload that would otherwise remain unactioned. During the period of the outsourced arrangements (from October 2007 to 31 December 2011), the ATO has referred just under 1.8 million debt cases, with a combined value of approximately USD 7 billion, to the ECAs for collection action. Of this amount, the ECAs have collected just over USD 2 billion, or 29.1% of the total debt referred, at a cost of USD 54 million in ECA fees. (NB: The ATO’s contracts with ECAs are based exclusively on a flat fee payment structure. The ATO, as a general principle, does not link debt collection to employee remuneration, and has extended this principal to the arrangement with ECAs. Commission-based pricing has not been used at any stage of the outsourced arrangements. In approximately 50% of referred cases, ECAs achieve either payment in full, or negotiate payment arrangements with taxpayers.

The ECAs have collected a significant amount of debt, generating very few taxpayer complaints and there have been no known breaches in the security of taxpayers’ data. At the operational level, the ATO has successfully implemented a comprehensive arrangement that was, at the time, a new approach to collecting tax and superannuation guarantee charge debt. However, at the strategic level, the ATO could more effectively set out how the referral program is integrated with the ATO’s broader approach to debt management, and the comparative advantages that underpin the use of ECAs.

Source: The Engagement of External Debt Collection Agencies (by the Australian Taxation Office), Australian National Audit Office (June 2012).

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

190 – 5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES

The non-tax roles of national revenue bodies

Reference was made in Chapter 1 to the practice of Governments allocating “nontax related roles” to revenue bodies and the rationale for doing this (see Table 1.6). To demonstrate the significance of this development, Table 5.7 provides data on the estimated proportion of each revenue body’s budget expenditure attributable to non-tax functions for 2005 to 2011 (where available). The key observations are as follows:

Rates of expenditure on non-tax functions appear relatively constant over the period 2005 to 2011, suggesting little further recent movement in this practice.

Responsibility for customs administration is the predominant source of non-tax expenditure in many countries (e.g. Argentina, Austria, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Mexico, Netherlands, and Romania) although the amounts/ proportions reported vary considerably – from 15 to almost 50% – for reasons that have not been identified.

In the case of countries such as Canada and New Zealand, responsibility for Government welfare/benefit-related responsibilities appear to be the primary influencing factor, and in the case of New Zealand are a significant element of overall expenditure (at 35%).

Table 5.7. Expenditure on non-tax roles (% of total revenue body expenditure)

(Table only shows countries that reported one or more non-tax roles for 2010/11)

|

|

Non-tax expenditure (as % of total revenue body expenditure) |

|

Main non-tax role(s) performed by |

||||

Country |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

revenue body (where known) |

OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australia |

14 |

9 |

11 |

15 |

12 |

13 |

16 |

Superannuation/retirement |

Austria |

- |

- |

- |

23 |

24 |

30 |

31 |

Customs,welfare, labour market laws |

Belgium |

28 |

28 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

33 |

35 |

|

Canada |

10 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

16 |

15 |

Welfare/benefits |

Czech Rep. |

5 |

2 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Denmark |

13 |

13 |

13 |

10 |

10 |

34 |

36 |

Customs |

Estonia |

- |

- |

- |

56 |

56 |

56 |

55 |

Customs |

France |

42 |

42 |

42 |

41 |

40 |

40 |

40 |

Public accounting functions |

Hungary |

0 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

13 |

0 |

26 |

Customs |

Ireland |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Customs-not quantified |

Israel |

- |

- |

- |

11 |

11 |

21 |

21 |

Customs-not quantified |

Mexico |

14 |

15 |

14 |

15 |

21 |

19 |

20 |

Customs |

Netherlands |

20 |

20 |

20 |

28 |

28 |

29 |

29 |

Customs, benefits |

New Zealand |

25 |

30 |

31 |

36 |

35 |

38 |

35 |

Welfare/benefits |

Norway |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

n.a. |

Population register |

Portugal |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

Property valuation |

Spain |

- |

- |

- |

14 |

15 |

n.a |

n.a |

Customs – not quantified |

Sweden |

17 |

17 |

15 |

9 |

9 |

15 |

17 |

Population register |

Switzerland |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

5 |

11 |

10 |

|

United Kingdom |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

Non-OECD countries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Argentina |

- |

- |

- |

51 |

51 |

51 |

49 |

Customs |

Brazil |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

n.a. |

n.a |

Customs – not quantified |

Colombia |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

45 |

45 |

Customs |

Hong Kong,China |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9 |

10 |

Business registration |

Latvia |

- |

- |

- |

22 |

17 |

52 |

48 |

Customs |

Romania |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

0 |

18 |

15 |

Customs |

Russia |

- |

- |

- |

15 |

15 |

13 |

14 |

|

South Africa |

- |

- |

- |

14 |

7 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

Customs – not quantified |

Source: CIS survey responses.

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013

5. RESOURCES OF NATIONAL REVENUE BODIES – 191

Notes

1.For survey purposes, IT expenditure was defined as the total costs of providing IT support for all administrative operations (both tax and non-tax related). Survey responses suggest that a fair number of revenue bodies were not able to readily isolate total IT-related expenditure.

2.For survey purposes revenue bodies were asked to quantify the actual or estimated costs of providing all human resource management support functions (e.g. personnel, payroll, recruitment, learning and development) for administrative operations (incl. non-tax roles).

3.For example, this practice is followed by revenue bodies in Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, Slovenia, South Africa, United Kingdom, and United States.

4.These ratios have been computed using data provided by surveyed revenue bodies for this and prior editions of CIS; for a very few countries (e.g. Cyprus and Germany), the ratios for years before 2010 that appeared in prior editions of the CIS have been revised to correct errors detected in their previous compilation by the countries concerned.

5.For survey purposes, the following definitions were used: 1) Taxpayer account management: All functions associated with maintaining taxpayers’ records (e.g. registration, data processing, taxpayer accounting, filing, withholding tax administration, storage etc.); 2) Audit, investigation and other verification functions: all staff on functions associated with verifying (either through field visits, office interviews or in writing) the information contained in taxpayers’ returns for all taxes administered by the revenue body; and 3) Human resource management: Refers to personnel, recruitment, and staff training and development (policy and administration) related functions and work; 4) Other corporate support: Refers to all information technology, accommodation, corporate planning, supply, security, internal assurance, public relations and finance functions.

Notes to Tables

Table 5.1. Salary expenditure/total expenditure-tax administration

/1. Hungary: Data of the predecessor organisation: Tax and Financial Control Administration, before the merger. Italy: Total expenditure data for 2010 and 2011 relate only to revenue body; some prior year data may include other bodies involved with tax work (e.g.Equitalia); Sweden: Expenditure data (and related ratios) exclude costs of independent Enforcement Agency staff that conducts enforced debt collection activities.

/2. Hungary: Data of the National Tax and Customs Administration, after the merger of two predecessor organisations: Tax and Financial Control Administration and Customs and Finance Guard.

Table 5.2. IT and human resource management expenditure (% of all expenditure)

/1. Argentina: Ratio to total cost including customs; IT expenditure includes hardware and software equipment as well as all kind of services and technical assistance on this matter; Luxembourg: Only direct taxes. Spain: IT costs include only capital expenditures and external applications. Administrative costs and Wages of the IT Department (2,259 people that develop and manage the whole system) should be added.

Table 5.3. Cost of collection ratios (administrative costs/net revenue collections)

/1. Observations and conclusions based on the information in this table should pay close regard to the comments in the related text in this chapter.

/2. The year-by-year data is compiled from surveys conducted among revenue bodies around every two years. For CIS 2012, some prior year data items and related ratios (reported in previous editions of CIS) were

TAX ADMINISTRATION 2013: COMPARATIVE INFORMATION ON OECD AND OTHER ADVANCED AND EMERGING ECONOMIES – © OECD 2013