Индустрия перевода

..pdf

In order to avoid the issue of text length dependence [14, p. 20], we use computers to take a random selection of words (tokens) from each of the essays. In computer programme Wordsmith, standardized TTR is computed every n word as wordlist goes through each text file (By default, n = 1000), then calculated afresh for the next 1,000, and so on to the end of the text or corpus.

LD was calculated in two ways, with and without considerations of word frequency. Firstly, all grammatical words were marked based on O‟Loughlin (2001)‟s taxonomy [15, p. 20]. After the number of grammatical words and lexical words were counted, lexical density of each text was manually calculated, using the following equation:

LD= Total number of lexical words +Total number of grammatical words100.

In addition to the traditional measure of LD, another measure, creatively named as Weighted Lexical Density (WLD), was used to measure lexical density. In LD, all words are treated the same and every words are attached the same weight. In WLD, words are divided into two levels according to their degree of frequency. High-frequency lexical items as well as grammatical words were given half of the value of others as was suggested by O‟Loughlin. It can be assumed that WLD which includes a qualitative dimension to the calculation, would give more insight into lexical aspects of language proficiency thus this measure might be more discriminative. WLD should be expressed as:

WLD = |

N High-frequency Lexical Words 0.5 + N Low-frequency Lexical Words . |

|

|

N High-frequency Words 0.5 N Low-frequency Words |

|

Built on the research of programme vocabprofile (LEP) [11], WLD made a distinction between high-frequency and low-frequency words and attached different weight to them accordingly. Functional words and lexical words were again coded, using the framework as in calculating LD. Thus the WLD in this paper is calculated, using the following formula:

WLD |

N of Level 1 Lexical N of level 2 lexical 0.5 N of AWL + off-list |

|

|

. |

|

N of Level 1 Lexical N of level 2 N of Functional 0.5 N of AWL off-list |

||

4. Findings and discussion

As is mentioned above, the present research used three different tools to measure vocabulary proficiency. In addition to the quantitative approach, the present study will also probe into learners‟ scripts, or to make a comparison of learners‟ constructions to detect the distinctive lexical features for each writing level or each learning stage.

4.1. Findings and discussion of the cross-sectional studies

Research Question One: How do scripts of a higher level differ from those of a lower level in terms of vocabulary proficiency?

211

4.1.1. Quantitative findings

In order to address Research Question One, the means of different writing levels measured by three separate tools were concluded as follows:

Table 1 A comparison of the means of lexical proficiency over three learning stages

Writing Level |

|

Task 1 Essay |

|

|

Task 2 Essay |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

LD |

WLD |

|

TTR |

N |

LD |

WLD |

|

TTR |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low-level |

5 |

57.09 |

43.14 |

|

59.8 |

7 |

55.58 |

43.69 |

|

65.16 |

Moderate-level |

33 |

55.63 |

41.78 |

|

56.41 |

33 |

54.13 |

41.71 |

|

67.11 |

High-level |

10 |

57.66 |

43.04 |

|

58.5 |

8 |

55.08 |

42.41 |

|

69 |

Note: N = Number of scripts.

Table 1 above shows that all the measures, including LD, WLD and TTR, have arrived uneven group means across different writing-level groups. This may indicate that the result deserves further investigation.

Based on the initial impression made by Table 1 that there existed differences in vocabulary proficiency across writing-level groups, the results were further displayed by the following Figures 1 and Figure 2, with Task 1 and Task 2 put into separate figures:

|

Mean |

70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

lexical density |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

weigjted lexical den |

Mean |

|

|

|

sity |

|

40 |

|

TTR |

|

|

|

lower level |

Moderate level |

Advanced level |

|

|

level |

|

Level |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1. VocabularyFigure 1: Vocabularyrichnessof Task1 essays1 essaysover profiencyoverlevelsproficiency levels

One interesting finding in Fig. 1 above is that all the three measures of Task 1 essays point to the same direction that the development of lexical proficiency is not in a linear sequence. All the lowest values of the measures in Task 1 fall into moderate level groups. After a regression of vocabulary proficiency at moderate

212

writing level in Figure 1, scripts of higher levels show an increase in all three measures, though to a limited degree.

|

Mean |

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

70 |

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

lexical density |

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

weigjted lexical den |

Mean |

|

|

|

sity |

|

40 |

|

TTR |

|

|

|

lower level |

Moderate level |

Advanced level |

level |

Level |

|

Figure 2: Vocabulary richness of Task 2 essays over profiency levels

Fig. 2. Vocabulary richness of Task 2 essays over proficiency levels

The above Figure 2 indicates that the same trend happens to LD and WLD of Task 2 essays but not to TTR. Unlike the other two measures, TTR of Task 2 essays show an encouragingly linear increase from lower proficiency group to advanced proficiency group.

In order to have a deeper understanding of the initial finding, one-way ANOVA is run in terms of group means of vocabulary richness between scripts of different proficiency levels, firstly with Type 1 essays only and then with Type 2 essays only. Output of both ANOVA analysis indicates no statistically significant differences across the different proficiency groups either of Task 1 essays or of Task 2 essays, which means one has to be very cautious in interpreting the quantitative findings.

Numerical analysis, then, appeared to be of limited help in understanding the developmental pattern of lexical richness. To examine closely the lexical development pattern, scripts from different writing levels were selected for further scrutiny.

4.1.2. Qualitative findings

On account of the fact that learners‟ familiarity with certain topic might affect their performance and that it might be more revealing to compare linguistic knowledge based on the same topic, scripts in responding to the same topic were chosen for qualitative study. Altogether six scripts were selected, including two lower-level two moderate-level, and two advanced-level scripts.

The qualitative investigation seemed to find some interesting development trend of vocabulary proficiency, reported as follows: Scripts of different writing levels displayed different ability in handling adjectives. The advanced and moder-

213

ate level scripts made use of a variety of more specific, more explicit adjectives to show their opinion, while the lower levels tend to repeat the limited number of words to express themselves and most of the words were of high frequency. The similar result was noticed in the use of verbs or verb phrases.

A further investigation on the above constructions from different writing levels have revealed that scripts of moderate and higher levels show wider range of vocabulary by using more synonyms or multi-word items to express their ideas rather than repeat the previously used words like those of lower levels do, though little difference is found among moderate level and advanced level. What is more, scripts of higher level show more lexical density by using more semantically precise words or multi-words to articulate their thoughts. For example, “superstitious” seems to make better sense than “bad” when used to modify culture. “Modern” or “up-to-date” may be more revealing than “new’ when describing technology. “To explore” may be more impressive compared with “to find”, etc.

4.1.3. Discussion

Both quantitative and qualitative studies do indicate some general developmental pattern of vocabulary proficiency among different writing levels. However, when interpreting the result, one will have to take into account issues that may affect the reliability of the result, i.e. one may doubt whether the limited sample size is enough to be representative of all the language learners.

4.2. Findings and discussion of the longitudinal studies

Research Question Two: How do scripts of a later learning stage differ from those of a former learning stage in terms of vocabulary proficiency?

4.2.1. Quantitative findings

Within-subjective comparison was carried out in order to examine the development features of vocabulary proficiency across three learning stages as follows:

Table 2 A comparison of the means of lexical proficiency over three learning stages

Learning |

|

Task1 Essay |

|

|

|

Task 2 Essay |

||

stage |

N |

LD |

WLD |

TTR |

N |

LD |

WLD |

TTR |

Stage 1 |

16 |

56.31 |

42.41 |

5.19 |

16 |

54.03 |

41.74 |

66.73 |

Stage 2 |

16 |

55.8 |

41.9 |

57.97 |

16 |

54.56 |

41.84 |

66.9 |

Stage 3 |

16 |

56.51 |

42.22 |

58.44 |

16 |

54.91 |

42.78 |

67.79 |

Note: N = number of scripts.

In Table 2 above, LD and WLD show little difference from those of Task 1, but TTR of Task 2 is much higher than that of Task 1. This may confirm the assumption made previously that scripts of different genre types may elicit different lexical knowledge.

One-way ANOVA was run to compare the means of the three groups of different learning stages. The output of ANOVA suggested that the means of vocabulary richness at three different learning stages were not significantly different. This result might not be surprising since the time-span between two stages is only

214

4 weeks, a time interval that might be too short for learners to make significant differences.

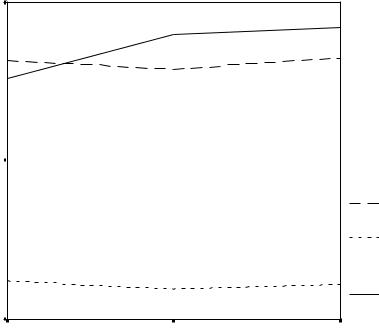

To make further investigation on the developmental sequence of vocabulary proficiency, Figure 3 and Figure 4 were drawn to illustrate the developmental pattern of vocabulary richness across three learning stages.

|

60 |

|

|

|

Mean |

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

lexical density |

|

|

|

weigjted lexical den |

Mean |

|

|

sity |

40 |

|

TTR |

|

|

learning stage 1 |

learning stage 2 |

learning stage 3 |

test time |

Test time |

Fig. Figure3. Vocabulary3: richnessof Taskof 1Taskes ays1ovessaysr le rningoverstageslearning stages

LD and WLD in Figure 3 show slight fluctuation of vocabulary richness over three learning stages, with a dip at middle stage. However, the dip may be too slight to deserve notice. The only exception is TTR in Figure 3, which increased steadily from Stage 1 to Stage 2 and remained stable until Stage 3.

Figure 4 shows three almost horizontal lines throughout learning stage 1 to learning stage 3, which means all of the three measures failed to discriminate vocabulary difference over different stages.

As is explained above, the short time-span of the present study may account for the fact that most of the measures failed to discriminate lexical performance over different stages.

4.2.2. Qualitative findings

To investigate the lexical development patterning of those essays, withinsubject observation was conducted by the present study. Closer scrutiny did detect lexical development of two subjects on Task 1 essays.

As can be observed in the scripts written by Subject 139, the script written at the first learning stage seems plain and unattractive since it tended to describe the trend shown by the diagram with almost purely object manner – no adverb is used to help readers to get better insight into the description; at the second learning stage, two adverbs are added to create more effective communication with the

215

readers. They are „decreased gradually‟ and „increased rapidly‟; at the third stage, five adverbs are noticed to modify verbs: “increase sharply”, “decrease grandly”,

“increases slightly”, “increase sharply”,and “drop quickly”.

|

Mean |

70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

lexical density |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

weigjted lexical den |

Mean |

|

|

|

sity |

|

40 |

|

TTR |

|

|

|

learning stage 1 |

learning stage 2 |

learning stage 3 |

|

|

test time |

|

Test time |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Vocabulary richness of Task 2 essays over learning stages

Figure 4: Vocabulary richness of Task 2 essays over learning stages

Scripts written by Subject 72 demonstrate the similar pattern over the three stages. At learning stage one, no modifier is found; script of Stage Two enriches itself by using some adverbs as well as adjectives, including “gradually decline”,

“steady increase”, “slight decrease”, “sharp increase” and “drop dramatically”; learning stage three also witnesses the similar lexical features, involving “increase gradually”, “went up steadily”, “increased sharply”.

The above findings seem to comply with the quantitative findings described in the previous section: learners have enriched their lexical knowledge rapidly during the EAP course, especially through Stage One to Stage Two. They tend to use more descriptive words to create more effective communication with readers. The reasonable explanation may be, again, that intensified vocabulary learning may make more effective acquisition.

4.2.3. Discussion on the findings of longitudinal studies

Quantitative study found little progress of lexical development through different learning stages. The only exception is that, from first learning stage to the second, learners rapidly enlarged their vocabulary range when writing Task 1 essays. The followed qualitative findings seemed to have confirmed this point.

A possible explanation may be that explicit learning through EAP cause makes much difference on vocabulary acquisition during the initial learning stage. This finding is in line with the discovery of Lee (2003) [16, p. 20] and Muncie

216

(2002) [17, p. 20] which suggested that explicit vocabulary learning might help newly-learned vocabulary become productive in an immediate task.

However, one must handle such interpretation with caution. The interval between two learning stage is only 4 weeks, a time-span that might not be extended enough to arrive a definite conclusion on developmental pattern.

Qualitative study did reveal that learners tend to use more descriptive words to help the readers to have a sharper insight into the content. However, this might not necessarily be the proof that the knowledge of these verbs or adjectives was newly-developed. Other possibility might be that the learners became more aware of the importance of effective communication with the readers through the training of the EAP course. It was likely that learners had known those descriptive words before. It is due to the raise of such awareness that learners begin to make more use of those words in writing.

5. Conclusion and future research

Throughout this research, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were conducted in order to obtain a greater understanding of the development of lexical proficiency across writing levels and across learning stages. Three measures of vocabulary proficiency were involved with an attempt to explore differences between writing levels or learning stages. However, none of the measures succeeded in detecting any significant differences. This may probably mean that the quantitative findings of the present study can only be interpreted as indicative rather than conclusive.

Quantitative studies found that there might be a dip in term of LD and WLD at proficiency level 2 but failed to give reasonably supportive explanation. TTR of Task 1 essays increase quickly from Stage 1 to Stage 2, which may give some implication for vocabulary pedagogy that explicit learning of vocabulary might make some difference. Genre type differences were reflected by the measure of TTR, which may indicate that test writer should apply different criteria to different genre types when describing vocabulary proficiency.

Qualitative studies across proficiency groups and learning stages did show that learners at a more proficient level and at a later learning stage tended to enrich their lexicon by using more diverse or semantically more precise lexical units to elaborate their thoughts or to make more effective communication with their readers. However, due to the fact that the qualitative studies were conducted within limited samples or within certain subjects, the findings might subject to much variation across individuals (see also [18, p. 20] for a discussion of individual differences in vocabulary use).

In all, the findings of the present project provide indicative but not constructive help for language teachers or researchers. Perhaps the greatest contribution of the present project would reside in its methodological implication for the future research. The following is the explanation:

1. Three measures of vocabulary richness are applied in this research. They are expected to reveal different aspects of vocabulary knowledge. However, one of the limitations of the study is that all three measures treat vocabulary in terms of individual words or word families. In other words, none of the measures take larg-

217

er lexical units, such as phraseology and idioms into consideration. Since words are likely to be acting in conjunction with other words [19, p. 20; 20, p. 20], it might be sensible for future research to highlight the analysis of larger lexical units.

2. The new measure WLD proposed in this research seemed to be a much refined tool to measure lexical density because it adds qualitative dimension to the quantitative approach. However, throughout the research this measure has not shown obvious prestige over the traditional LD in that all the findings of WLD are similar to those of LD. One may doubt whether all the efforts that had made in discriminating high-frequency and low-frequency vocabulary is worthwhile. Perhaps it is time for researchers to reconsider the concept of “quality” of vocabulary. Perhaps “frequency” might not be the only criteria in judging the quality of vocabulary. As is indicated by qualitative studies of this research, learners make more impressive use of vocabulary by using words or phrases that can articulate their thoughts more precisely or that can communicate with their readers more effectively. Does this imply another direction for future research, that is, to judge the quality of vocabulary from semantic or pragmatic approach?

References

1.Raimes A. What unskilled ESL students do as they write: a classroom study of composing // TESOL Quarterly. – 1985. – 19. – P. 229–258.

2.Santos T. Professors‟ reactions to the academic writing of non-native speaking students // TESOL Quarterly. – 1988. – 22. – P. 69–88.

3.Engber C.A. The relationship of lexical proficiency to the quality of ESL compositions // Journal of Second Language Writing. – 1995. – 4. – P. 139–155.

4.Read J. Assessing vocabulary in a second language // Encyclopedia of language and education. Vol. 7. Language testing and assessment / ed. C. Clapham, D. Corson. – Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publisher, 1997. – P. 99–107.

5.Haastrup K., Henriksen B. Vocabulary acquisition: From partial to precise comprehension // Travaux de l‟Institut de linguistique de Lund. Vol. 38.

Perspectives on lexical acquisition in a second language / ed. K. Haastrup,

A.Viberg. – Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press. – P. 97–114.

6.Meara P.M. Connected words: word association and second language vocabulary acquisition. – Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009.

7.Schneider M., Connor U. Analyzing topical structure in ESL essays: Not all topics are equal // Studies in Second Language Acquisition. – 1990. – 12 (4). – P. 411–427.

8.Bachman L.F. Statistical analysis for language assessment. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. – P. 85–87.

9.Read J. Assessing vocabulary. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

10.McCarthy M. Vocabulary. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

11.Laufer B., Nation P. Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production // Applied Linguistics. – 1995. – 16. – P. 307–322.

218

12.Schmitt N., Schmitt D., Clapham C. Developing and exploring the behaviour of two new versions of the Vocabulary Levels Test // Language Testing. – 2001. – 18 (1). – P. 55–88.

13.Meara P., Jones G. Eurocentres vocabulary size test (Version E1.1/K10, MSDOS). – Zurich: Eurocentres Learning Service, 1990.

14.Tweedie F., Baayen R.H. How variable may a constant be? Measures of lexical richness in perspective // Computers and the Humanities. – 1998. – 32. – P. 323–352.

15.O‟Loughlin K. Studies in language testing 13: The equivalence of direct and semi-direct speaking tests. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

16.Lee S.H. ESL learners‟ vocabulary use in writing and the effects of explicit vocabulary instruction // System. – 2003. – 31. – P. 537–561.

17.Muncie J. Processing writing and vocabulary development: comparing lexical frequency profiles across drafts // System. – 2002. – 30. – P. 225–235.

18.Dewaele J.M. Individual differences in the use of colloquial vocabulary: the effects of sociobiographical and psychological factors // Vocabulary in a second language / ed. P. Boggaards, B. Laufer. – Amsterdam: John Benjemins Publishing Company, 2004. – P. 127–153.

19.Sinclair J.M., Renouf A. A lexical syllabus for language learning // Vocabulary and language teaching / ed. R. Carter, M. McCarthy. – London: Longman, 1988. – P. 140–160.

20.Schmitt N. Vocabulary in language teaching. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

И.В. Смирнова

Пермский национальный исследовательский политехнический университет

К.М. Лебедева, А.В. Назарова

Пермский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет

КОМПЕТЕНТНОСТНЫЙ ПОДХОД В РОССИЙСКОМ ОБРАЗОВАНИИ

Рассматривается реализация компетентностного подхода в российском образовании. Проанализированы компетенции, формируемые у детей дошкольного возраста, школьников и студентов высших учебных заведений. Описываются понятия «компетенция» и «компетентность», «профессиональная компетенция», сравниваются ключевые компетенции школьников, дошкольников и студентов.

Ключевые слова: компетентностный подход, компетенция, компетентность, модернизация, профессионализация.

Компетентностный подход сегодня олицетворяет собой инновационный процесс в российском образовании. Он рассматривается как один из способов достижения нового качества образования, как «радикальное средство модернизации образования». В проектах новых государственных стандартов предполагается закрепление одинакового набора общих компетенций

219

для одного направления образования. При этом число компетенций возрастает при переходе на более высокий уровень образования. Формирование каждой компетенции должно обеспечиваться определенным набором дисциплин (или практик), объединенных в соответствующие модули, а содержание модулей дисциплин – полностью соответствовать уровню этих компетенций.

Анализ литературы по проблеме компетентности показал ее многогранность. Эти понятия используются учеными, педагогами в разных контекстах, поэтому появляется необходимость в уточнении данных понятий для дальнейшего их использования в работе. По мнению, Л.В. Свирской, в настоящее время как в образовательной теории, так и на практике происходит своеобразная экспансия понятий «компетентность», «компетенция», «компетентностный подход». Это связано, с одной стороны, со следованием тенденциям мировой образовательной практики (следствие глобализации и открытости). С другой стороны, с пониманием ложности пути изменения образовательной практики единственно на основе совершенствования способов подачи знаний, умений и навыков, и с третьей, с пониманием необходимости ориентации образования на готовность учащегося к активной самостоятельной и совместной деятельности.

В толковом словаре иностранных слов «Компетентность» определяется как «обладание компетенцией; обладание знаниями, позволяющими судить о чѐм-либо». Таким образом, компетентность является более широким понятием и включает в себя компетенции. «Компетенция» в данном словаре рассматривается как «круг полномочий какого-либо органа или должностного лица; круг вопросов, в которых данное лицо обладает познаниями, опытом». В словаре С.И. Ожегова «компетентность» также определяется как «осведомленность», «авторитетность». А «компетенция» – как «круг вопросов, в которых кто-нибудь хорошо осведомлѐн». Таким образом, и «компетентность», и «компетенция» – это обладание знанием, но при этом компетенция – это более узкий круг знаний, определенный опытом субъекта.

Далее обратимся к пониманию понятий «компетентность» и «компетенция» ученых-исследователей в области педагогики. Вопросам осмысления категорий «компетенция» и «компетентность» посвящено множество исследований, среди которых труды И.А. Зимней, В.И. Загвязинского, Г.В. Селевко, А.В. Хуторского и др. Можно отметить, что нет единства во взглядах относительно данных понятий: одни считают их синонимичными (Л.Н. Боголюбов, Н.Д. Рыжаков) или «почти синонимичными» (Г.К. Селевко), другие разграничивают их, соотнося как часть и целое (И.А. Зимняя, А.С. Прутченков, Б.И. Хасан). Так, И.А. Зимняя отмечает, что «компетенции» – некоторые внутренние потенциальные скрытые психические новообразования (знания, представления, программы действий, системы ценностей и отношений), выявляющиеся в компетентностях человека как актуальных деятельностных проявлениях.

Т.А. Ратт также подчеркивает необходимость разделять понятия «компетенция» и «компетентность» в образовании, понимая под компетенцией некоторое отчужденное, заранее заданное требование к образовательной под-

220