Biomedical EPR Part-B Methodology Instrumentation and Dynamics - Sandra R. Eaton

.pdf

342 |

|

DEREK MARSH ET AL. |

where |

and |

and transitions are induced by the |

in the spin system i = k. summing over all i yields the further condition:

Solution of Eqs. 49 and 50 again yields the standard expression for saturation (see Eq. 46) where the effective spin-lattice relaxation time is given by (Marsh, 1992a):

The exchange frequency is  which gives the dependence on spinlabel concentration, N, and

which gives the dependence on spinlabel concentration, N, and  is the fractional population (or degeneracy) of the transition being saturated.

is the fractional population (or degeneracy) of the transition being saturated.

For powder spectra, the intensity of the non-linear out-of-phase spectrum is reduced without change in lineshape (Marsh and Horváth, 1992b). The effects of Heisenberg exchange are therefore readily distinguished from those of rotational diffusion. When the degree of degeneracy is high

as in a powder pattern, a large number of states is available for redistribution of saturation. Heisenberg exchange then has the same effect as a true relaxation enhancement, rather than a cross-relaxation. The effective relaxation rate is then simply:

which is found to be applicable in many practical situations with low exchange rates.

8.2Paramagnetic Enhancement by Heisenberg Exchange

Spin-lattice relaxation is induced by Heisenberg spin exchange only if the paramagnetic species comes into direct contact with the spin-label. For strong exchange, the enhancement in spin-lattice relaxation rate is given by the product of the collision rate constant,  and relaxant concentration,

and relaxant concentration,  (Molin et al., 1980):

(Molin et al., 1980):

344 |

DEREK MARSH ET AL. |

different ions, k, is given by the Solomon-Bloembergen equation for electron spins (Bloembergen, 1949; Solomon, 1955):

where  and

and  are the Larmor frequencies of the paramagnetic ion and spin label, respectively,

are the Larmor frequencies of the paramagnetic ion and spin label, respectively,  is the separation of the spin label from the paramagnetic ion,

is the separation of the spin label from the paramagnetic ion,  is the angle between the interdipole vector

is the angle between the interdipole vector  and magnetic field direction,

and magnetic field direction,  is the electron gyromagnetic ratio, and

is the electron gyromagnetic ratio, and

is the magnetic moment operator of the paramagnetic ions. The spectral densities are defined by

is the magnetic moment operator of the paramagnetic ions. The spectral densities are defined by  where

where  is the spin-lattice relaxation time of the paramagnetic ion. The latter is assumed to be sufficiently short that it also determines

is the spin-lattice relaxation time of the paramagnetic ion. The latter is assumed to be sufficiently short that it also determines  i.e.,

i.e.,  The terms

The terms  involving the angle

involving the angle  are related to the absolute values of the corresponding spherical harmonics. Summation is over the entire distribution of paramagnetic ions, k.

are related to the absolute values of the corresponding spherical harmonics. Summation is over the entire distribution of paramagnetic ions, k.

Volume integration for paramagnetic ions distributed in the aqueous phase, or surface integration for ions adsorbed at the lipid-water interface, yields values of  that depend on the distance of closest approach, R, of the paramagnetic ions to the spin label, and on the angle

that depend on the distance of closest approach, R, of the paramagnetic ions to the spin label, and on the angle  between the magnetic field and the membrane normal (Livshits et al., 2001). For macroscopically unoriented membrane dispersions, different parts of the powder pattern will saturate differently. However, the dependence of

between the magnetic field and the membrane normal (Livshits et al., 2001). For macroscopically unoriented membrane dispersions, different parts of the powder pattern will saturate differently. However, the dependence of  (static) on

(static) on  is much weaker than the initial dependence on

is much weaker than the initial dependence on  Therefore, for reasonable estimates of the saturation behaviour of the integrated spinlabel EPR intensity, one can average

Therefore, for reasonable estimates of the saturation behaviour of the integrated spinlabel EPR intensity, one can average  (static) over

(static) over  The resulting angular-independent effective values of

The resulting angular-independent effective values of  (static) are (Livshits et al., 2001):

(static) are (Livshits et al., 2001):

SATURATION TRANSFER SPECTROSCOPY |

345 |

for volume and surface distributions, respectively, where:

and |

are the bulk and |

surface paramagnetic ion concentrations, and |

||

|

with |

as the Bohr magneton. For |

and |

|

ions, |

and all three terms in Eq. 58 contribute, whereas for |

|||

and |

and the first term in |

dominates. |

|

|

Table 3 gives numerical estimates of the static dipolar  enhancements for a spin label situated at R = 1 nm in lipid membranes that are immersed in a 30 mM paramagnetic ion solution. For ions with S > ½,

enhancements for a spin label situated at R = 1 nm in lipid membranes that are immersed in a 30 mM paramagnetic ion solution. For ions with S > ½,

both the estimates of |

and the experimental values of |

depend on the |

||

way in which zero-field splittings are taken |

into account (Livshits et al., |

|||

2001). The values of |

(static) are predicted to be rather small and in the |

|||

order |

for paramagnetic ions other than |

The latter |

||

has favourable values |

of both |

and spin, |

that give rise to efficient |

|

paramagnetic relaxation enhancements, but it has an EPR spectrum at room temperature, which complicates analysis of the saturation behaviour of the spin-label spectrum. For strongly absorbed paramagnetic cations, the values

346 |

DEREK MARSH ET AL. |

of  may be increased by up to a factor of ten, because of the smaller average distance from the spin label.

may be increased by up to a factor of ten, because of the smaller average distance from the spin label.

Static dipolar interactions modulated by the fast relaxation of the paramagnetic ion also contribute to  relaxation. These contributions influence both progressive saturation studies and also linewidth measurements. In standard Leigh theory (Leigh Jr., 1970), the strong angular dependence of the dipolar relaxation for two isolated dipoles results in practically complete quenching of all resonances other than those for dipole pairs oriented at the magic angle. The much weaker angular dependence resulting from integration over a distribution of paramagnetic ions (cf. above), results in a line broadening rather than an amplitude quenching. The resulting effective transverse relaxation rates,

relaxation. These contributions influence both progressive saturation studies and also linewidth measurements. In standard Leigh theory (Leigh Jr., 1970), the strong angular dependence of the dipolar relaxation for two isolated dipoles results in practically complete quenching of all resonances other than those for dipole pairs oriented at the magic angle. The much weaker angular dependence resulting from integration over a distribution of paramagnetic ions (cf. above), results in a line broadening rather than an amplitude quenching. The resulting effective transverse relaxation rates,  (static), are given by (Livshits et al., 2001):

(static), are given by (Livshits et al., 2001):

where

For  and

and  ions

ions  the first term in

the first term in  dominates which gives

dominates which gives For

For  and

and  ions

ions

on the other hand, all terms in the spectral density contribute and

on the other hand, all terms in the spectral density contribute and

Table 3 gives numerical estimates of |

again for R = 1 nm |

|||

and 30 mM bulk concentration of paramagnetic ions. Values for |

|

|||

and |

are comparable to those for |

whereas for |

(and to |

|

a lesser |

extent |

for |

For |

ions, |

|

is 50 times greater than for |

ions, and in turn is 10-20 times |

||

less than for |

ions. |

|

|

|

SATURATION TRANSFER SPECTROSCOPY |

347 |

8.3.2Dynamic Dipolar Relaxation

In the case of rapid translation diffusion, spin-label relaxation can be induced by modulation of the dipolar interaction by the mutual diffusive motions of the spin labels and paramagnetic ions. The criterion that the dynamic mechanism dominates over the static mechanism is  where

where  is the translational diffusion coefficient and

is the translational diffusion coefficient and  is the distance of closest approach between paramagnetic ion and spin label. Unlike the situation with relaxation by diffusion-controlled Heisenberg spin exchange, the dynamic dipolar interaction is much more significant for

is the distance of closest approach between paramagnetic ion and spin label. Unlike the situation with relaxation by diffusion-controlled Heisenberg spin exchange, the dynamic dipolar interaction is much more significant for  than for

than for  because of the contribution from spectral densities at low frequency. Assuming that spectral densities at the Larmor frequency and above contribute negligibly, the

because of the contribution from spectral densities at low frequency. Assuming that spectral densities at the Larmor frequency and above contribute negligibly, the

enhancement is (Abragam, 1961):

enhancement is (Abragam, 1961):

where the zero-frequency spectral density is  and for

and for  whereas for

whereas for

The

The  enhancement therefore becomes:

enhancement therefore becomes:

where  for

for  (i.e., specifically for

(i.e., specifically for  and

and  for

for  (i.e., for most other ions).

(i.e., for most other ions).

The dynamic dipolar enhancement in  on the other hand, is:

on the other hand, is:

i.e., |

for |

and |

for |

Therefore, for ions with g-values that differ considerably from that of the spin label  the dynamic dipolar

the dynamic dipolar  is expected to be small. For ions with g-values close to those of the spin label

is expected to be small. For ions with g-values close to those of the spin label  viz.,

viz.,  the

the  enhancement is:

enhancement is:

i.e., two-fifths that |

of the dynamic dipolar |

rate. Strictly |

speaking, the latter |

condition requires equality |

of Larmor frequencies. |

348 |

DEREK MARSH ET AL. |

Therefore, hyperfine structure of the paramagnetic ion can be a complicating factor.

9.APPLICATIONS: RELAXATION ENHANCEMENTS

This section gives examples of the applications of nonlinear EPR to the different mechanisms of saturation transfer that were described in Section 8. They span reasonably well the range of different nonstandard types of STEPR experiment.

9.1Two-site exchange: lipid-protein interactions

The rate of exchange of spin-labelled lipids at the intramembranous perimeter of transmembrane proteins is relatively slow and two-component conventional  spectra are resolved when the rotational mobility differs in the two membrane lipid environments (Horváth et al., 1988). Nonlinear EPR methods, both progressive saturation EPR and

spectra are resolved when the rotational mobility differs in the two membrane lipid environments (Horváth et al., 1988). Nonlinear EPR methods, both progressive saturation EPR and  have been used to detect and measure exchange of lipids on and off the protein (Horváth et al., 1993).

have been used to detect and measure exchange of lipids on and off the protein (Horváth et al., 1993).

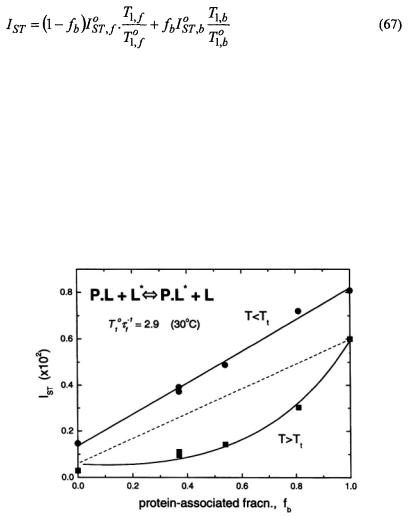

Figure 12 gives the integrated  intensity,

intensity,  as a function of the fraction,

as a function of the fraction,  of spin-labelled lipid that is associated with the myelin proteolipid protein in reconstituted membranes. Samples all have the same total lipid/protein ratio;

of spin-labelled lipid that is associated with the myelin proteolipid protein in reconstituted membranes. Samples all have the same total lipid/protein ratio;  is varied by using spin-labelled lipid species with differing affinities for the protein. The value of

is varied by using spin-labelled lipid species with differing affinities for the protein. The value of  is determined by spectral subtraction with the two-component conventional

is determined by spectral subtraction with the two-component conventional  EPR spectra (Marsh and Horváth, 1998). Below the lipid chain-melting temperature,

EPR spectra (Marsh and Horváth, 1998). Below the lipid chain-melting temperature,  any exchange is extremely slow and the normalised saturation transfer intensity,

any exchange is extremely slow and the normalised saturation transfer intensity,

is simply additive depending linearly on

is simply additive depending linearly on

where  and

and  are the values of

are the values of  for lipid-alone and protein-alone samples, respectively. In the fluid lipid phase, above

for lipid-alone and protein-alone samples, respectively. In the fluid lipid phase, above  the dependence of

the dependence of  on

on  lies below the straight (dashed) line expected for no exchange. Saturation is partially alleviated by exchange between sites on and off the protein at rates comparable to the spin-lattice relaxation time.

lies below the straight (dashed) line expected for no exchange. Saturation is partially alleviated by exchange between sites on and off the protein at rates comparable to the spin-lattice relaxation time.

Assuming that  is approximately proportional to

is approximately proportional to  (see Fig. 11), the net ST-EPR intensity in the presence of exchange is given by:

(see Fig. 11), the net ST-EPR intensity in the presence of exchange is given by:

350 |

DEREK MARSH ET AL. |

9.2Spin-Spin Interactions

This section gives two different examples of the application of ST-EPR techniques to measuring weak spin-spin interactions from the dependence on spin concentration in single-labelling experiments. One example is the use of Heisenberg exchange to determine slow translational diffusion at relatively low label concentrations. The second example is the use of local spin-spin interactions to detect protein oligomer formation. In a third subsection, examples are given of the use of spin-spin interactions detected by nonlinear EPR to determine the membrane location of spin-labelled proteins, relative to spin-labelled lipids, in double-labelling experiments.

9.2.1Spin exchange: diffusional collisions

A significant example of the use of non-linear EPR to determine lowfrequency collision rates from Heisenberg exchange interactions is offered by the translational diffusion of integral membrane proteins (Esmann and Marsh, 1992). The importance of the non-linear spin-label EPR method is that it measures local diffusion coefficients which then may be compared with long-range diffusion detected by such standard techniques as photobleaching (Clegg and Vaz, 1985).

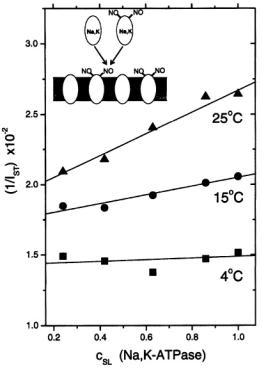

Figure 13 gives the dependence of the reciprocal  intensity,

intensity,  on concentration,

on concentration,  of spin-labelled Na,K-ATPase in membranes reconstituted at a constant total lipid/protein ratio equal to that of the native membrane. Given that the integrated second-harmonic out-of-phase absorption intensity,

of spin-labelled Na,K-ATPase in membranes reconstituted at a constant total lipid/protein ratio equal to that of the native membrane. Given that the integrated second-harmonic out-of-phase absorption intensity,  is approximately proportional to the

is approximately proportional to the  time (see Fig. 11), the relaxation enhancement with increasing spin label concentration found in Fig. 13 is described by the following relation (cf. Eq.

time (see Fig. 11), the relaxation enhancement with increasing spin label concentration found in Fig. 13 is described by the following relation (cf. Eq.

52):

where  and

and  are the values of

are the values of  and

and  in the absence of spin exchange and

in the absence of spin exchange and  is the second-order rate constant for spin exchange between spin-labelled proteins. The latter is related directly to the collision rate constant,

is the second-order rate constant for spin exchange between spin-labelled proteins. The latter is related directly to the collision rate constant,

where the probability of exchange on collision is for strong exchange and

for strong exchange and  is the normalised collision cross-section. Thus the gradients with

is the normalised collision cross-section. Thus the gradients with

SATURATION TRANSFER SPECTROSCOPY |

351 |

increasing spin-label concentration in Fig. 13 give the normalised exchange rate constant,  and hence the collision rate constant. Translational diffusion coefficients are extracted from the latter by using specific models.

and hence the collision rate constant. Translational diffusion coefficients are extracted from the latter by using specific models.

Figure 13. Reciprocal integral intensity,  of the second-harmonic out-of-phase absorption

of the second-harmonic out-of-phase absorption  ST-EPR spectra as a function of the fractional concentration,

ST-EPR spectra as a function of the fractional concentration,  of spinlabelled Na,K-ATPase in reconstituted membranes of fixed lipid/protein ratio

of spinlabelled Na,K-ATPase in reconstituted membranes of fixed lipid/protein ratio  lipid phosphate/mg protein) at the temperatures indicated. Solid lines are linear regressions. The inset indicates the mode of reconstitution by recombining complementary fractions of solubilised spin-labelled and non-spin-labelled protein (see Esmann and Marsh, 1992).

lipid phosphate/mg protein) at the temperatures indicated. Solid lines are linear regressions. The inset indicates the mode of reconstitution by recombining complementary fractions of solubilised spin-labelled and non-spin-labelled protein (see Esmann and Marsh, 1992).

Both a quasi-crystalline lattice model and the two-dimensional diffusion equation with Smoluchowski boundary conditions yield similar values for the translational diffusion coefficients:  and

and  at 15°C and 25°C, respectively (Esmann and Marsh, 1992). These values are comparable to those predicted by the Saffman and Delbrück (1976) hydrodynamic treatment for two-dimensional diffusion with a membrane viscosity of

at 15°C and 25°C, respectively (Esmann and Marsh, 1992). These values are comparable to those predicted by the Saffman and Delbrück (1976) hydrodynamic treatment for two-dimensional diffusion with a membrane viscosity of

and to those determined for various other large transmembrane proteins reconstituted at high dilution in lipid membranes

and to those determined for various other large transmembrane proteins reconstituted at high dilution in lipid membranes

is the translational diffusion coefficient of the relaxant (that of the spin-labelled system is assumed to be negligible by comparison),

is the translational diffusion coefficient of the relaxant (that of the spin-labelled system is assumed to be negligible by comparison),  is the interaction distance between relaxant and spin label,

is the interaction distance between relaxant and spin label,  is a steric factor,

is a steric factor,  is the electrical charge on the relaxant, and

is the electrical charge on the relaxant, and  is the electrostatic surface potential of the spin-labelled system. The enhancement in relaxation rate by Heisenberg spin exchange is therefore determined by the diffusionconcentration product, plus any electrostatic interactions. In the case of membranes, the local value of the product

is the electrostatic surface potential of the spin-labelled system. The enhancement in relaxation rate by Heisenberg spin exchange is therefore determined by the diffusionconcentration product, plus any electrostatic interactions. In the case of membranes, the local value of the product  at position

at position  time.

time. times,

times,  of the paramagnetic species that are much shorter than the characteristic dipolar correlation time,

of the paramagnetic species that are much shorter than the characteristic dipolar correlation time,  for translational diffusion. Dynamic dipolar relaxation, i.e., the second case, dominates at the opposite extreme, when the dipolar correlation time is much shorter than the spinlattice relaxation time of the relaxant.

for translational diffusion. Dynamic dipolar relaxation, i.e., the second case, dominates at the opposite extreme, when the dipolar correlation time is much shorter than the spinlattice relaxation time of the relaxant. and

and  are the spin-lattice relaxation times at lipid locations respectively off and on the protein, and

are the spin-lattice relaxation times at lipid locations respectively off and on the protein, and  are the corresponding values in the absence of exchange. Combining Eq. 67 with Eq. 47 and its equivalent for

are the corresponding values in the absence of exchange. Combining Eq. 67 with Eq. 47 and its equivalent for  gives the predicted dependence of

gives the predicted dependence of  on

on  in the presence of exchange. The non-linear least-squares fit shown in Fig. 12 yields a normalised on-rate constant for lipid exchange of

in the presence of exchange. The non-linear least-squares fit shown in Fig. 12 yields a normalised on-rate constant for lipid exchange of  (at fixed lipid/protein ratio of 37:1 mol/mol and T = 30°C). From this the offrates

(at fixed lipid/protein ratio of 37:1 mol/mol and T = 30°C). From this the offrates  for the lipids with different affinities for the protein are determined by the relation

for the lipids with different affinities for the protein are determined by the relation  for detailed balance (see Eq. 40).

for detailed balance (see Eq. 40). intensity,

intensity,  from different spinlabelled lipids on the fraction,

from different spinlabelled lipids on the fraction, of each lipid species associated with the myelin proteolipid protein in dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine membranes (lipid/protein = 37:1 mol/mol). Measurements are made in the gel-phase

of each lipid species associated with the myelin proteolipid protein in dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine membranes (lipid/protein = 37:1 mol/mol). Measurements are made in the gel-phase  and in the fluid phase

and in the fluid phase  at 4°C and 30°C, respectively. Solid lines are fits of Eqs. 67, 47 and equivalents obtained by a linear regression at 4°C and non-linear least squares fit giving a normalised lipid exchange rate of

at 4°C and 30°C, respectively. Solid lines are fits of Eqs. 67, 47 and equivalents obtained by a linear regression at 4°C and non-linear least squares fit giving a normalised lipid exchange rate of  at 30°C. The dashed line is the dependence expected for no exchange at 30°C (see Horváth et al., 1993).

at 30°C. The dashed line is the dependence expected for no exchange at 30°C (see Horváth et al., 1993).