Engineering and Manufacturing for Biotechnology - Marcel Hofman & Philippe Thonart

.pdfTranslating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

10.Timing

10.1.U.S. APPLICATION FILING

The United States offers a one-year grace period from first publication, use, or sale of an invention within which to file for a patent. Within that one year, an inventor can file a patent application with no loss of  rights. After one year, no patent is possible.

rights. After one year, no patent is possible.

Other than Canada, the rest of the world does not offer any grace period. The world system is one of “absolute novelty.” Publication, use, or sale of an invention prior to filing a patent application eliminates the possibility of international patent protection. Filing an U.S. patent application prior to first publication, use, or sale is sufficient to preserve international rights. In those instances in which the European rights were destroyed by untimely disclosure, it is still possible to apply for a patent in the US. The grace period is also useful with “ iffy” inventions. Given the availability of one year in which to manufacturing and market an invention, it may be possible to determine if a real market advantage exists, prior to investing patenting costs. Such a scenario is more likely with near term products such as diagnostic and screening methodologies. Note that U.S. patent applications have previously been maintained (more or less) in confidence and not publicly disclosed until issued as a patent. US applications filed after November 29, 2000 will be published at 18 months from the earliest priority date unless the US applicant agrees not to file international counterparts. In the rest of the world, patent applications are published 18 months from the earliest priority date.

10.2. ON-SALE BAR TO PATENTABILITY

Europe limits patentability to an “absolute novelty” standard. The US offers a one-year grace period after disclosure use or sale of an invention in which to file a patent application. Europe and the US, however, apply different criteria for acts which place an invention “on sale" The surprising result of the differential is that an invention might be unpatentable in the US by reason of exceeding the one-year grace period for patent filing, but remain patentable in Europe under the seemingly more strict absolute novelty standard.

10.2.1. Out source disaster

In the United States, after an invention has been “on-sale” (or made public) for more than one year, it is not possible to obtain a patent. The “on-sale” bar is an absolute to patentability. Of late, the courts have been defining “on-sale” quite expansively. Under recent judicial constructions of “on-sale,” the “sale” of a novel compound or compound made by a novel process can be found within the transaction between a contract manufacturer and the contracting party. This “sale” starts the one-year clock.

The sale/non-sale determination may turn on such housekeeping issues as invoicing and accounting of payments between the contracting party and the manufacturing party. If the contract manufacturer is being paid to research and develop a process, or by “time and materials,” it may be arguable that there is no “sale” taking place. If invoicing is

479

Thomas M. Saunders

per unit (weight, batch, etc.), there may be a sale. This seems particularly problematic when ordering a nucleotide or protein from a supply service. Even when a transaction is “confidential,” the contracting party places an order for a specific novel nucleotide or protein, and the exact composition is created and placed in commerce – often over night. This looks like a sale.

One response to the on sale worry is to labour over each out-sourcing agreement and have excellent trial counsel. Another is to file any likely patent application within the year. To effectively respond to the danger of an unrecognised premature “sale,” keep patent counsel apprised of all out source agreements and results. Patent applications tend to be easier to draft if the patent attorney (i) knows of the invention, and (ii) has fixed an outside date for patent application filing.

10.2.2. Concept offered for sale

Under US law, an invention can be “on-sale,” even if the invention is yet to be reduced to practice.

A case recently decided by the Supreme Court dealt with an inventor who designed, but did not build, a new computer chip socket7. Drawings of the socket were sent to a manufacturer and shown to Texas Instruments before the critical date one year prior to filing the patent application, but no manufacturing was begun until after the critical date. The Supreme Court granted review specifically to address the question of whether there can be a sale prior to a reduction to practice. The answer is yes.

The Court read the patent statutes as making no requirement for reduction to practice. Thus, it reasoned, an invention was actually invented when drawings or other descriptions had been prepared “that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention8.”

Consider the situation of a protocol for series of gene manipulations to yield a particular therapeutic or diagnostic result. If the protocol were complete to the point at which a post-doctoral fellow or a clinician (“a person skilled in the art”) could follow the protocol and obtain the result at least some of the time, any commercial activity after that date could begin the one-year clock. Note, too, that even if the method by which the effect of the invention is to be achieved remains secret, a sale can be consummated. Thus, an offer to a laboratory to provide a diagnostic genomic screen, if offered at the time at which a written protocol existed to accomplish that particular screen, could well be on-sale activity under the current rule.

The safe course is to avoid any disclosure or commercial activity in advance of filing for a patent. Such “premature” patent application efforts are a necessary trade-off for obtaining secure patent protection, and may necessitate filing supplemental patent applications later as the imagined protocol encounters laboratory realities.

7 Pfaff v. Wells Electronics, Inc., 48 U.S.P.Q. 2d 1644(1998).

8 Pfaff 48 U.S.P.Q. 2d at 1642.

480

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

10.3. INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION FILING

10.3.1. Priority dates

By various treaties, the US will accept international filing dates and the rest of the world will accept the US filing date as the priority date for applications filed within one year of an original application. To file internationally, the basic choices are to file under the Patent Co-operation Treaty (“PCT”), or to file directly in a specific countries and/or regions. In particular, a US filing or a filing in any country of Europe it is possible to file directly in the European Patent Office (“EPO”) designating 17 countries in Europe (including all the major countries).

10.3.2. Internationally file the CIP

The vanilla US based company patent strategy is to file a US application on work actively underway, and then, just prior to one year from US filing, update the US application in the form of a CIP. It is then the CIP which is simultaneously filed in the US (replacing the original US application), and worldwide. A US first procedure (or home country and US) is also available to international applicants.

10.3.3. Filing costs

Filing in the PCT currently costs about $164 for each designation up to 11 designations, and peaks at about $3000 total with additional fees to designate the entire world including transmittal fees, yearly fees, and other basic fees. There are even additional fees for applications in excess of 30 pages. Ultimately, designating the world is just a holding action pending getting a major partner. This is because at 30 months one is faced with paying to enter each country, which generally makes no sense.

In the PCT, by, at most, 30 months, an application must enter the national stage. At that point, the PCT application ends and the application exists only in each country or regional patent office (e.g., EPO). At the 30 month point, the cost to enter the national stage in each country of Europe is about $15,000 total. Entering Canada is about $1,500, Japan about $4,000, and Australia about $2,000. In the end, anticipate paying $70,000 for Europe and $50,000 for Japan through to issue.

10.3.4. The EPO option

One option is to avoid the PCT and file directly by region or country. This makes sense when the countries of interest are the usual suspects. In our view, this means the EPO, and Canada, with Japan and Australia as likely additions. The distinction between PCT and direct filing is that, while expenses incurred at 30 months in the PCT are incurred at

12 months by direct filing, in most cases the initial expense is lower with direct filing.

One clear advantage is that by avoiding the PCT one avoids a number of procedural pitfalls that can derail an application. On the other hand, using the PCT offers the seeming advantage of an option to drop an application before certain fees are required.

This dropping advantage is only realised if the underlying technology is found inoperative in that period between 12 and 30 months when a PCT application must go

481

Thomas M. Saunders

to the national stage. In practice however, no new data arises and no applications are dropped in this window. It is sad but true that incurring the PCT expenses in the hope that BigPharma will eventually pay extra because rights in the former Soviet empire (or somewhere) never pays off. In the aggregate the costs are more at the front and not enough at the back on the one hit. Remember that these expenses will be incurred on every patent application for every project, while a deal will only apply to a few patents or patent applications at a later date.

1 0.3.5. Country selection

Patents exist on a country-by-country basis. A US patent can only be enforced in the

US; a French patent, only in France. Do not pursue patents in countries without effective enforcement systems. This is a basis for espousal of limiting foreign filings to the EPO and Canada, and, maybe, Japan. While Australia has an efficient judicial system, an effected population may be too limited. Remember that the costs are incurred now, while revenue will not be generated until later, if ever.

One cost sensitive licensing point is agreeing to extensive international filings only if fully paid for by the licensee. The rub comes when licensor’s corporate staff time is

not reimbursed. Patent prosecution in the more exotic countries requires numerous notarisations by state and consular officials and represents a substantial time burden. Agreeing to such filings with BigPharma is not a deal breaker, but be quick to suggest that their patent counsel handle these matters at their expense.

10.3.6. Annuity fees

Many countries charge yearly fees on pending applications and on issued patents.

These fees increase as the patent portfolio increases and ages, forming a constant and substantial drain on finances.

11. Patent Position in Action

“We aren’t worried about their patents, we have one of our own.”

11.1PATENT CLAIMS VERSUS PRODUCTS

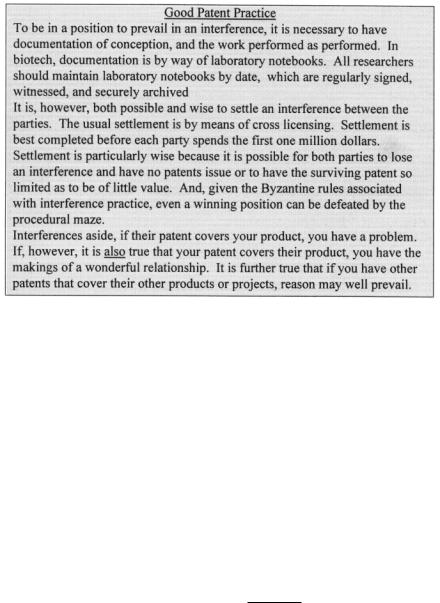

Patent infringement arises from any claim of one party’s patent covering another party’s product or process. The issue is never Patents v Patents except in fighting it out within the US Patent Office to prove that your side is first to invent. This means that in the US, a patent applicant who is second in time of filing (the “junior party”) can obtain a patent over an earlier filed patent application (senior party) if the junior party can establish earlier “conception,” “reduction to practice” and, usually, some level of “diligence.” These elements are determined in the context of an intra-Patent Office proceeding termed a “patent interference.”

482

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

This report is not a legal treatise, and the exact meaning of these terms will not be developed here to a legal certainty. Should you find yourself in an interference, the terms will be explained to you for in excess of $1,500,000 in the first year of proceedings. And if you are junior by more than about three months, you are unlikely to be pleased with the explanation.

11.2. LITIGATION VERSUS LICENSE

11.2.1. Litigation

The absolute minimum tab for a US patent suit is $1,000,000 -- to the courthouse steps. Of course, such bargains are rarely available. And forget finishing litigation. A few years of legal bills of several hundred thousand dollars per month brings most people to the table. The winner in litigation (other than the lawyers) cannot be predicted with certainty. Litigation is extremely distracting to that centre of the company that is responsible for advancing the corporate scientific front. In start-up biotechnology, this may be only five or ten people.

11.2.2. Licensing

If a license is taken, there is no infringement. If the problem is thought to be rather speculative, consider taking the license or option to a license at a lower price. The reduced price represents the tenacity of the position of the patent holder.

Taking a license is the only step that absolutely disposes of a potential infringement problem.

483

Thomas M. Saunders

Unless counsel says that there is no conceivable infringement issue, take the license -- if available -- under even minimally acceptable terms. With the uncertainty and expense of litigation, a license now can represent a great saving.

11.2.3. More timing

Be clear on timing. There may be no real problem of infringement. U.S. patents have had a 17-year life span, though some drugs secure a Patent Term Extension of up to 5 years based on a patent having issued prior to FDA approval. Under the new GATT rules that became effective in June of 1995, U.S. pharmaceutical patents will generally have a considerably shorter life span, based on a maximum of 20 years from filing. If the blocking patent is some years post-issue, and the product horizon for sale after FDA approval is some years off, there may be no problem. If it is anticipated that, subsequent to FDA approval of your product, the remaining term of the blocking patent will be brief, one may look to international sales to bridge this restricted period. Of course, this presumes that there are countries other than the U.S. presenting reasonable commercial prospects, and lacking patent coverage. Raising these alternative strategies with a recalcitrant patent holder may also bring them into agreement.

11.3. SURVIVAL CLAIM READING

11.3.1. Look only to the words of the claims

Do not be distracted by what the patent is "really" directed at, or whether or not the underlying science is bogus.

11.3.2. Element-by-element comparison

If a claim recites elements A, B, and C, does the product in question have each element? Having A, B, C, and D usually does not avoid the fact that you also have A,

B, and C. It follows that A, B and D is not A, B, and C and is clear of infringement. Also, note the distinctions between and and or.

11.3.3. Numerical claim limitations

A concentration or amount recited in a claim can provide a bright-line distinction to define infringement.

11.3.4. Ignore predicate phrases

Predicate or preamble phrases such as "A composition for growing hair" do not comprise a limitation of the claimed invention. If the potential blocking patent claims composition has A, B, and C, and your composition has A, B, and C, there is substantial cause for concern -- even if the intended use of your composition has nothing to do with hair growth. One bottle of A, B, and C looks pretty much like another bottle of A, B, and C.

484

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

11.3.5. Terms of art

In U.S. practice, certain terms have very specific meanings in patentees, not equalled in general usage: "comprising" v. "consisting of." In patentees "comprising" means the thing recited, and anything else. In contrast, "consisting of" means a rather strong limit

to the recited elements. "Consisting essentially of" means almost exactly the recited elements.

11.3.6. Definitions

The issue of coverage, validity, or infringement may turn on the specific meaning attributed to a given term. If a claim recites "lower alkyl alcohol" how many carbons does "lower" mean? A hierarchy of definitions is applied. What the patentee stated in the patent or in the file history will determine this meaning first. If neither patent nor file history defines this term, then one may look to its general definition in the art.

Be sure to check the patent for a definition of all the critical terms before infringement is ruled in or out. In almost every patent, a unique definition is applied to some claim term that may rule infringement in or out.

11.3.7. File wrapper estopped

If the applicant retreated from one position to a narrower position to avoid some prior art, this retreat forms an outer boundary of claim scope. The patentee is "estopped" from attempting to regain in court that which was surrendered in the Patent Office. The corollary here is that if one practices what was given up in prosecution of the blocking patent, one is in a "safe haven" where infringement is not possible (as to that patent).

11.3.8. Things that won't help

11.3.8.1. Different product. The product the bad guys make does not define or reflect

what their patent claims, or is totally distinct from your product. It is their patent claims against your product. Their product has nothing to do with it.

11.3.8.2. Junk Science. Bad underlying science generally will not remove a claim or destroy a patent. Patents are not journal papers written to prove and convince. Patents are merely recipes that are required to work much of the time, if followed. And even if the broad claims are wildly optimistic, specific narrow claims may fall within the range of reality.

12. Digging for patent dirt

12.1. FILE HISTORIES

Obtain full file histories of all licensed patents, patent applications, and all related applications and patents. The file histories of issued patents are publicly available documents. This is true in the U.S. and Europe. In the U.S., file histories of pending applications are confidential documents of the Patent Office, and not publicly available.

485

Thomas M. Saunders

12. 2. COMPUTER SEARCHING

The INPADOC (INternational PAtent DOcumentation Center) database provides a means to generate a printout of all countries where a patent application has been filed and the current status as to each country.

Another database is the Derwent World Patent Index. A computer search of patents and patent publications on the Derwent data base (1963 to present) can uncover international patents and patent applications, whether or not issued. In the free-to- market context, the real point of a Derwent search is to uncover pending US patent applications. The search output identifies all countries in which the application is pending. The Derwent information is less than conclusive because the 18-month delay creates a window of uncertainty to be recognised. Confirm the identity of what you are buying as to related applications and patents, and which countries. As noted above an INPADOC search is a quick check on what is out there for the patents and patent applications under consideration.

A number of new on-line search options are available on the Web or by fax.

These include

•the US Patent Office (http://www.uspto.gov)

•an IBM patent site (http://patent.womplex.ibm.com),

•the European Patent Office (http://dips.patent.gov.uk/dips/gb/en/level 1 .htm),

•MicroPatent Services (http://www.micropat.com),

•Corporate Intelligence (http://www.first.com/).

Conclusion

The pharmaceutical industry lives on proprietary technology. Patents comprise the major proprietary element. Building a patent portfolio requires timely attention.

Timely, under these circumstances, means before the validity or value of the invention are proven. Building a patent portfolio also requires large infusions of cash. Building a marketable patent portfolio requires foresight (which is often indistinguishable from luck.).

486

INDEX

ABA............................................................................................................................... |

434 |

Activated carbon......................................................................................................... |

33, 34 |

Alcalase ........................... |

39, 40, 41, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 |

Alcalase® .............................................................................. |

51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 |

Alginate ......................................................................... |

280, 283, 285, 286, 289, 307, 415 |

Anaerobic ............................................................................................................... |

145, 155 |

Anticancer...................................................................................................................... |

430 |

Antitumor ....................................................................................................................... |

431 |

Aspergillus........................................................ |

...28, 43, 48, 62, 63, 73, 74, 109, 313, 320 |

B5 .................................................................................. |

433, 434, 436, 437, 438, 440, 444 |

Bacillus licheniformis...................................................23, 28, 52, 155, 171, 172, 178, 179

Bead....................................................................................................................... |

295, 300 |

Beer ....................................................................... |

273, 275, 285, 289, 290, 291, 292, 399 |

Beer fermentation .......................................................................................................... |

285 |

Bicarbonate.................................................................................................................... |

216 |

Bioencapsulation .................................................................................... |

290, 291, 293, 306 |

Biofuel........................................................................................................... |

449, 450, 454 |

Bioreactor...................................................................... |

216, 243, 245, 281, 283, 289, 449 |

Biotechnology2, 3, 21, 28, 37, 38, 58, 61, 111, |

127, |

140, |

141, |

155, |

171, 178, 200, 216, |

226, 238, 264, 275, 277, 307, 360, 375, 376, |

397, |

398, |

411, |

412, |

419, 420, 445, 446, |

447, 448 |

|

|

Bulk enzyme processing, challenges |

..............................................................................322 |

|

Bulk enzymes purification............................................................................................. |

|

321 |

Bulk enzymes, concentration......................................................................................... |

|

320 |

Bulk enzymes, harvest.................................................................................................... |

|

320 |

Bulk enzymes, production............................................................................................. |

|

318 |

Callus............................................................................ |

|

429, 433, 435, 436, 437, 438, 439 |

Callus cultures ............................................................................................................... |

|

429 |

Carbon dioxide ...................................................................................... |

|

145, 149, 205, 206 |

CER ............................................................... |

|

203, 204, 206, 208, 211, 212, 213, 215, 216 |

Cider .............................................................................................................................. |

|

290 |

Cod muscle...................................................................................................................... |

|

52 |

Common reed.................................................................................................................. |

|

30 |

Control28, 38, 77, 79, 84, 108, |

140, 141, 181, 200, 203, 216, 217, 225, 226, 262, 317, |

|

370 |

|

|

Corynebacterium glutamicum ............................................................. |

|

23, 25, 26, 156, 216 |

Crossflow ultrafiltration ......................................................................................... |

|

171, 174 |

487

Data reconciliation................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

183, 184, 189, 193, 195, 199 |

|||||

DEAE cellulose carrier................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

271 |

||

Economy........................................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

Entrapment ............................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23, 258, 280, |

307, 413, 414 |

|||||

Enzyme stabilisation............................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

371, 376 |

||

Estimation................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63, 104, 127, 140, 141, 155, 200, 216 |

|||||||

Ethanol.......................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

l49, 289, 376 |

|||

Experimental design...................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

128, 130, 158 |

|||

Fermentation28, 29, 37, 73, |

116, |

120, |

127, |

140, |

141, 200, 217, 218, 221, 225, 267, 276, |

||||||||||||||

288, 289, 360, 414, 425 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Fibrobacter succinogenes.... |

|

......................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

157, 158, 161, 162, 164, 165, 167 |

||||||||

Flavour development..................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

261 |

|

Fluidised bed reactors............................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

269, 282 |

||||

Fructose ................................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

149, 151, 336, 434 |

||||

GA3.............................................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

434 |

|

Gas lift draft tube reactor systems |

................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

264 |

||||||

Glucose23, 123, 145, 149, 151, 158, 161, 165, 166, 185, 221, 222, 223, 314, 336, 366, |

|||||||||||||||||||

371, 375 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glutamic acid............................................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23, 28 |

|

Glutamic acid, Production .............................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

||

Hemicellulose........................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29, 37 |

|

HPLC.............................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31, 436, 445 |

|||

Hydrolysis................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22, 40, 41, 44, 46, |

52, |

53 |

|||

IMAC............................................................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

340 |

|

Immobilisation253, |

272, |

277, |

278, |

290, |

291, |

293, |

294, |

296, |

307, |

369, 420, 421, |

432, |

|

|||||||

434, 442, 444 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Immobilised cel ............................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

257, 267, 275, 289, 290, 291, 413, 414, 419 |

||||||||||

Immobilised cells................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

290, 419 |

||

Immobilised primary fermentation............................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

263 |

||||||

Immobilised yeast system.............................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

271 |

||

Intelligent bioreactor ..................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

450 |

||

Internal loop gas-lift reactor.......................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

285 |

||||

Kalman Filter........................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

203, 204, 208, 209, 210, 211, 215, 216 |

|||||||

Kinetic model ................................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

84 |

Kinetin.......................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

434, 436, 444 |

|||

Lactic acid ..................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

29, 30, 35, 37, 399, 400, 401, 402, 408, 410, 411, 412 |

|||||||||||||

Lactic acid bacteria.......................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30, 399, 400, 401, 402, 408, 410, 411, 412 |

|||||||||

Licensing ....................................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

483 |

Loop reactor systems..................................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

265 |

|

Mass balances................................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

67 |

Mathematical models.......................................................................................... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

61, 64, 73 |

||||

Matrix design................................................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

257 |

Media............................................................................................ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

216, 376, 433, 436, 446 |

||||

Metabolic flux ................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

74, 143, 145, 151, |

155, 156, 159, |

167, 216 |

|||||||

Metabolic network................................................................................................. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

161, 162 |

||

488