Engineering and Manufacturing for Biotechnology - Marcel Hofman & Philippe Thonart

.pdfTRANSLATING EUROPEAN BIOTECH INTO US PATENTS

DO’S, DON’TS, & COSTS

THOMAS M. SAUNDERS

Lorusso & Loud

Boston, MA, USA Fax: +(617)723-4609; tmsaunders@aol.com

Introduction

Start-up biotechnology begins with an idea. European start-up biotechnology must consider how these ideas for novel drugs and methods will make the trans-Atlantic crossing to access the US market. Given the huge costs of US Food & Drug

Administration (FDA) approval, exclusivity is a threshold requirement of new drug development. US patent portfolios are a means to exclusivity. Without the potential for exclusivity, it may be impossible to justify the cost of regulatory approval. Without potential exclusivity, intellectual property licensing income or venture capital for product development will not be available. This report considers significant differences between European and US patent systems, and offers suggestion patent strategy to develop a biotech patent portfolio.

1. Five important patent differences between Europe and the US

1.1. ONE-YEAR US GRACE PERIOD FROM FIRST USE OR SALE

One European rule for patentability is “absolute novelty.” Absolute novelty means that disclosing an invention -- such as by delivering a talk or selling the thing invented -- is fatal to patentability. In contrast, the US offers a one-year grace period from first disclosure. Thus, in those instances in which the European rights were destroyed by untimely disclosure, that disclosure will not prevent applying for a patent in the US.

1.2. GRACE PERIOD (CONTINUED): TEMPUS FUGIT

The US definition of “sale” differs from the European definition. Under US law, outsourcing of a product or process may constitute a “sale” back to the hiring party.

This “sale” will (perhaps) start the one-year clock. It also is possible to have an invention “on-sale" which has been designed but not built. For example, purchasing a

459

M. Hofman and P. Thonart (eds.), Engineering and Manufacturing for Biotechnology, 459–486.

© 2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

Thomas M. Saunders

novel nucleotide from an outsource can place the nucleotide “on sale.” Soliciting business under a prepared protocol for a series of gene manipulations to yield a particular therapeutic or diagnostic result, if complete to the point at which a postdoctoral fellow or a clinician (“a person skilled in the art”) could follow the protocol and obtain the result at least some of the time, could be deemed placing it “on-sale,” thus starting the one-year clock.

1.3. DUTY OF DISCLOSURE

A European patent applicant has no specific requirement to inform the European Patent Office of significant prior art. In the US there is a duty of absolute candour. While no search need be made, an applicant in the US is responsible for informing the Patent

Office of any art of which it is aware.

1.4. COMPUTER ALGORITHMS NOW PATENTABLE

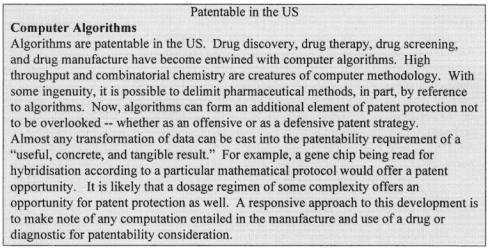

Another recent court decision confirmed that computer algorithms are now patentable.

This reversed a line of decisions that held algorithms to be “mere mathematical formulae” and unsuitable for patent protection.

1.5. FIRST TO INVENT VERSUS FIRST TO FILE

In the US, a patent is awarded to the “first to invent.” In Europe and most of the world, a patent is awarded to the “first to file.” This means that a later-filing patent applicant (the “junior party”) can obtain a patent over an earlier-filing patent applicant (senior party) if the junior party can establish earlier “conception,” “ reduction to practice,” and

(usually) some level of “diligence.” These elements are determined in the context of an intra-Patent Office proceeding termed a “patent interference.”

Drug discovery, drug therapy, drug screening, and drug manufacture have become entwined with computer algorithms. High throughput and combinatorial chemistry are creatures of computer methodology. With some ingenuity, it is possible to delimit pharmaceutical methods, in part, by reference to algorithms. Now, algorithms can form an additional element of patent protection not to be overlooked -- whether as an offensive or as a defensive patent strategy

2. Basic patent game theory

• Only market exclusivity can justify the huge cost of drug regulatory approval.

•Market exclusivity can arise from either the patent system or (occasionally, in the

US) from the FDA.

•Patent protection holds out the promise of market exclusivity, augmented profit margins, and great wealth.

•As a consequence, patents hold out the promise of wildly expensive litigation (the only kind).

460

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

•Applying for and obtaining a biotechnology patent in the US costs about $20-

30,000, and about another $70,000 for all of Europe.

•For start-up biotechnology, tens of patent applications will be filed now, and the

money paid now, for (maybe) one marketable patented product years down the road. IP applicants must plan on patent expenses of no less than $250,000 per year.

•The object of the game is to have patent protection for what it is you sell, and still avoid bankruptcy.

3. Invention germination

A technology venture must take pains to encourage disclosure of inventions. Inventive ideas are not limited to the senior scientists. One ignores post-doctoral students and technical staff at the company’s peril. One way to obtain the disclosure of inventions is by invention disclosure forms.

3.1. INVENTION DISCLOSURE FORMS

3.1.1. Short forms only

While any number of forms can be devised, our view is that a form should be as brief as possible. The function of a disclosure form is merely that of prompting a corporate representative to  with the inventor. At that meeting, a skilled representative can inquire more fully into the invention and document the necessary information. Nothing is less conducive to unearthing inventions than requiring completion of a multi-page disclosure form with no feedback. From a legal perspective, it is foolhardy to offer an inventor a detailed questionnaire and then base corporate patent actions (or inaction) on those answers without further inquiry by the patent staff.

with the inventor. At that meeting, a skilled representative can inquire more fully into the invention and document the necessary information. Nothing is less conducive to unearthing inventions than requiring completion of a multi-page disclosure form with no feedback. From a legal perspective, it is foolhardy to offer an inventor a detailed questionnaire and then base corporate patent actions (or inaction) on those answers without further inquiry by the patent staff.

3.1.2. Who gets the forms?

Submitting invention disclosures directly to an invention committee or its representative

(even if copied to supervisors) causes some problems and avoids others. From experience, we assure you that there is a real or imagined concern among inventors that a supervisor will suppress an invention or at least ask to “approve” a submission and try to claim inventorship. To avoid this concern, direct submission to a committee is useful. With direct submission, less-secure supervisors may interpret such submissions as theft of their own ideas. Periodic group idea sessions with minutes may be a partial solution. Another method is by simultaneous submissions to supervisor and committee.

Mandatory lithium is a possibility. Call us if you come up with a better idea.

461

Thomas M. Saunders

3.2. NO FORMS

A very useful approach for unearthing inventions is direct and frequent contact between all scientific personnel and the patent point person. The point person walks into all the labs at least every other week and asks what people are up to. Regular visits and interested inquiry from a source that is not “checking to see if you are working” is superior to invention disclosure forms, productivity reports, project summaries, E-mail, and everything else. Even a follow-up visit to an invention disclosure filing should prompt the patent point person to inquire beyond the basic disclosure. A comprehensive inquiry should include attention to a scientist’s guesses, hunches, and views of what data are or will prove significant.

4. Invention selection

In the non-pharmaceutical world, there are guidelines for selecting which inventions or intellectual property (IP) to pursue as patents. “Almost as good and a lot cheaper”

sells. Also, things that work better but cost more can be sold. In the pharmaceutical world, marketing “almost as good” is close to impossible. In the pharmaceutical world, at the time the patent money is being spent, you will have no idea if it works at all, let alone better. In the pharmaceutical world, most things don't work.

sells. Also, things that work better but cost more can be sold. In the pharmaceutical world, marketing “almost as good” is close to impossible. In the pharmaceutical world, at the time the patent money is being spent, you will have no idea if it works at all, let alone better. In the pharmaceutical world, most things don't work.

4.1. IP FOCUS

What business are we in? Read your business plan or stock offering. If the technology under consideration is not at the heart of your business, expending time and money on a patent application is ill advised. First, technological judgement and market savvy drop off logarithmically as the distance between the discovery and the main business increases. Second, the ability to enjoy the profit potential of a patent is substantially based on being the source of the product or process employed. If the idea is a great one for some other business, that is a bad sign.

The “our business” test should be an expansive test considering the vertical aspects of your business. Will the discovery be the subject of further inquiry in the 12 months following conception? If the answer is “no,” the technology is probably not central.

Be realistic. Breakthrough compounds emerge only rarely. In contrast, advantageous process and delivery technology improvements emerge more often and with a higher likelihood of commercial usefulness. Thus, super-producer clones, essential filtration steps, and dosage form architecture should not be overlooked as sources of IP. A patent at a process bottleneck (read “choke point”) can offer market position, trade goods for other essential technology, an entree to cooperative relationships, and a royalty stream.1 In fact, in a crowded field, it is often reasonable to maintain exclusivity by assembling a collection of tiny impediments to duplication and

1 Rats form the major component of the tiger’s diet in the wild. They are easy to catch and, in quantity, provide for most nutritional needs.

462

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

encroachment in the form of “picket patents.” With enough patents in an area, “metoo” producers may be dissuaded from entering a market unless the total market rises above perhaps $50,000,000. There is a patent litigation adage that say if one is being sued under multiple patents it is most unlikely to avoid all the claims of infringement. And a single claim of infringement will carry the day. Thus, a multiple patent arsenal is particularly protective of a commercial position.

4.2. THE LEARNING CURVE

Biotech patent applications are often filed at very early stages following conception.

This can mean filing even before the first mouse has been dosed. In the US, a patent is typically filed on limited early data and then repeatedly refiled as continuing data arise. There is a one-year period between the US filing2 and worldwide filing.

4.3. THE STAR WARS TEST

If the invention works as planned, do you anticipate that multiple Nobel Prizes would be awarded? This is nature’s way of telling you that the likelihood of success is limited in a field accustomed to limited success.

4.4.IS THERE A MARKET?

4.4.1.Money

If the primary indication is a small population, a patent might not be justified or required. Orphan drug designation may be a cheaper alternative. Also, if the market is small enough, how attractive will such a market be to the generic houses? Below about $25,000,000 annual sales there may be no reason to seek a patent.

4.4.2. Perceived need

Does the world know that this technology is required? Such a threshold question was answered affirmatively as to NMR and liposome drugs. Betaseron for the symptomatic treatment of MS has run into marketing problems because MS patients are not prepared to undergo early severe side effects, whatever the benefit. In contrast, side-effect resistance does not limit the market for cancer chemotherapeutic agents.

2 Under some circumstances, a second European application can be filed prior to a point 18 months from the US filing date. As this is not a treatise on patent prosecution, some nuances of timing and law will be simplified. For more specific answers, contact patent counsel.

463

Thomas M. Saunders

5.Points of decision

5.1.PATENT COMMITTEE

It is useful to establish a patent committee that meets, perhaps, quarterly (but certainly not more often than monthly). Representation on the committee should include Research, Development, Business Development, Marketing, and Patent Counsel. Each inventor should be invited to plead his or her case.

5.2. RATINGS

5.5.1. A = File immediately

The invention is at the core of our technology. We intend to make a product embodying this technology. Work is being done on this technology now or will begin immediately.

A’ (a rare ancillary consideration) The invention covers a technological cusp which we are sure that a competitor must traverse, but which the competitor may have overlooked. [This sounds plausible but never pans out.]

5.5.2. B = Review in six months

This could prove interesting if more data were available. It is not at the heart of our business. At the review point there will only be more data if the proponent has been

464

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

able to find the time, money, and personnel. If this has not occurred, the corporation has voted. The disclosure can be rolled over for additional periods or await other events such as the failure of a preferred line of inquiry.

5.5.3. C = Indefinite hold

The idea appears clever to non-experts. It is not germane to our business or to our competitors. The invention can be revisited if circumstances change.

It is important not to inhibit the willingness of the scientists to offer ideas by rating the ideas as “unusable, forever, under any circumstances” (though a smoke detector with a snooze alarm comes close).

5.2.3.Hard financial facts

Basic exemplary calculations include attributing about $40,000 to $50,000 in the first 4 years for each maintained application that is filed internationally.

Presuming 10 patent applications are filed yearly:

First year costs: $100,000 -- ($90,000 legal, $10,000 patent fees)

This covers $10,000 for a totally new application, and rather less for a similar application, and some costs. For an accelerated delineation of the likely patent position, filing in the US from the outset may be indicated. This can be accomplished as a US filing without filing initially in the home country, or as parallel initial filings.

Second year costs: $165,000 -- ($110,000 legal, $55,000 patent fees)

In the second year, filing 10 new patent applications as before will cost another $100,000. Perhaps 5 of the earlier patent applications will require responses to the Patent Office adding another $20,000

Entering the PCT at the one year mark on the first 10 applications will add about another $30,000. Seven months thereafter (at 19 months) one must file a demand for preliminary examination at about $1,500 each, or $15,000.

Third Year Costs: $405,000 -- ($150,000 legal, $255,000 patent fees)

465

Thomas M. Saunders

In the third year, filing 10 new patent applications as before will cost another $100,000. Perhaps 15 of the earlier patent applications will require responses to the Patent Office adding another $60,000

As before, entering the PCT at the one year mark on the next 10 applications will add another $30,000. Again, at the 19-month point the demands for preliminary examination add $15,000. And now at 30 months, entering the national stage on will cost perhaps $200,000.

In the fourth year it is reasonable to expect some patent applications to be supplanted by later applications, while others are abandoned outright. There may be a levelling off of the necessary responses to the Patent Office, but the responses may be more difficult, and hence more expensive. Offsetting any reduction, however, will be an increase in the need to respond to patent actions in the EPO. These tend to mirror responses in the US, but are not without cost. Adding up the foregoing and assuming $330,00 for the fourth year, the 4-year total is $1,000,000.

From experience there is an initial wave of filings in the first six month of corporate life. Thereafter -- and with considerable variability -- patent applications begin to emerge from research projects about 18 months after wet lab begins. At that point five or six process and product applications will be suitable for filing. Surely, the technology of your corporation will offer its own peculiar maturation time. However, once this time is known it will generally repeat forming a useful guideline for budgeting purposes.

6. Its just business

In a proprietary-obligate industry, the patent position being sought is, in many respects, no more than a reflection of corporate direction. If a start-up biotechnology or pharmaceutical technology company is sufficiently confident in the potential for success of a technology, and sufficiently committed to devote the resources to develop this technology, the patent position will follow.

6.1. WHAT IS IT REALLY WORTH TO DEVELOP AND MAINTAIN YOUR PATENT PORTFOLIO?

•Question. How do you exploit its value?

•Answer. It depends.

6.2.THE ONE TRUE ANSWER.

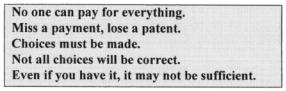

•Nothing in life is simple.

•Decisions must be made (really).

• |

The points of decision are subjective. |

• |

Making the best decision is a matter of luck and don’t let anyone tell you different. |

•Making a reasonable decision that maximises the potential for a favourable outcome is a matter of skill.

466

Translating European biotech into US patents do’s, don’ts, & costs

Based on the factors above, a few helpful hints are offered (and life is no more certain than that).

If you really believe you’re an extraordinarily high-tech company, then you’re almost certainly spending a lot of money and taking risks. So, the conclusion is that you shouldn’t take such risks without high likelihood of broad patent protection, right? Well, yes and no. In pharmaceuticals, yes! Yes, because (1) the product will probably be on the market for many, many years; (2) your FDA filings make it fairly easy for people to copy you with all the time they’ll have; and (3) the markets are big enough that people will make money even with a small share if they’ve piggybacked on your favourable outcome without the risks.

Interestingly, while broad patents are generally better than narrow ones, a narrow patent can be valuable in this field.3 For example, while even a slight change can avoid a narrow patent, e.g. replacing ethyl with butyl, it will still send the competitor back to the beginning in the development, clinical and US regulatory maze, and add to the development cost and development risk.

Contrast this with a high (but not quite as high) tech field like diagnostics. The markets are smaller, and the life cycles shorter. Odds are that a narrow patent doesn’t keep out much competition. In addition, the years it takes to complete a major patent dispute, the products in question will be obsolete well before your lawyer has finished piling paper on the judge. It often makes more sense to spend the money on the next innovation instead of defending a patent. In businesses like diagnostics or software where the product/technology turnover is very rapid, speed, flexibility, and always getting there first with the next generation can be worth much more than a patent. Of course, there are exceptions. Some very broad patents exist in these fields too, and often available for license.

NB #1: Avoid patent directed experiments. Perform only those syntheses and experiments required within a development project. It is generally a waste of time, money, and effort to perform additional syntheses and experiments with the sole intention of generating data for expanded patent protection. In pharmaceuticals, most primary compounds fail. Thus, casting a net to cover the mere possibility of a secondary compound is ill considered.

Realise that in deciding what to patent and whether to go forward without one, the competition goes through the same thought process. If you don’t want to go forward without a patent base, others won’t either. That's why there are some great ideas that companies don’t pioneer. Aspirin for heart attack prevention, for example. A small company would be unlikely to spend money on a claim to that cardiac indication when the customer could use any of the many generic substitutes already available. Of course, in the US a large producer has expended the effort, but backed it up with a huge marketing push. In most instances “method of treatment” patent claims are only valuable when you can police use of the necessary drug.

3A “broad” patent has a broad main claim. This does not exclude quite specific “picture claims” exactly coinciding with the product to be marketed.

467

Thomas M. Saunders

NB #2: Policing uses. A method of using an OTC like aspirin can’t be controlled. If, however, the method were to a novel use of a drug with only a hospital application such as doxorubicin, policing would be an easy matter.

This leads to the “under the radar” approach. Without a patent, go for a market that’s big enough for you, but not big enough to attract the sort of big competition that needs a patent. Circular, but profitable. Example: A $10 million pharmaceutical market. Who’s going to bother going for it with no patent anyway? Get there first, and secure a niche market.

6.3. NICE PACKAGE

A first objective of any patent strategy is turning what you have into a licensable package you can market to a partner.

6.3.1. Human pharmaceuticals

No major pharmaceutical house puts serious money into anything unless they see the likelihood of a strong patent position. In large part, their analysis leads them there, and their huge fixed cost reinforces this position, but this is also a deep-rooted cultural practice that is unlikely to change. It would be a daring executive indeed who risked a clinical failure when the up side was only $50,000,000.

The elements of a licensable package are

•Good basic underpinnings of science

•Data -- Well designed experiments that truly illustrate your point in vitro and, if possible, in animals

•A clear articulation of how the science translates into products

•A simple story on why the all-critical technology is novel and why you will have

protection in the market, and not just a patent.

•Patent applications rather than issued patents have a potential that is yet to be defined (and cannot be dismissed). Issued patents are often less saleable.

6.3.2. Windage

Faster moving technological fields such as gene therapy have less defined patent requirements. This is not to say it does not have patent requirements. Gene therapy has pharmaceutical aspects in long development times, but vector and tool technology is changing daily. As a result, the potential value of the broader gene sequence patents and patented use of specific genes is undefined. If one is committed to such a technology, portfolio bulk is an important consideration. The hope is that some aspect of your proprietary technology will be useful for leverage in reaching any required accommodation with a competitor.

6.3.3. Exclusivity

Pharmaceutical players always want it. But diagnostics companies and others often settle for non-exclusivity. Ask yourself this: Does having all of the market for the few uses you can market on your own translate into more or less than a small piece of a truly

468