- •Contents

- •Foreword

- •1.1.1 Haemostasis

- •1.1.2 Inflammatory Phase

- •1.1.3 Proliferative Phase

- •1.1.4 Remodelling and Resolution

- •1.7 The Surgeon’s Preoperative Checklist

- •1.8 Operative Note

- •2.4.1 Local Risks

- •2.4.2 Systemic Risks

- •2.5 Basic Oral Anaesthesia Techniques

- •2.5.1 Buccal Infiltration Anaesthetic

- •2.5.2 Mandibular Teeth

- •2.5.2.1 Conventional ‘Open-Mouth’ Technique

- •2.5.2.2 Akinosi ‘Closed-Mouth’ Technique

- •2.5.2.3 Gow–Gates Technique

- •2.5.2.4 Mandibular Long Buccal Block

- •2.5.2.5 Mental Nerve Block

- •2.5.3 Maxillary Teeth

- •2.5.3.1 Greater Palatine Block

- •2.5.3.2 Palatal Infiltration

- •2.5.3.3 Nasopalatine Nerve Block

- •2.5.3.4 Posterior Superior Alveolar Nerve Block

- •2.6 Adjunct Methods of Local Anaesthesia

- •2.6.1 Intraligamentary Injection

- •2.6.2 Intrapulpal Injection

- •2.7 Troubleshooting

- •3.1 Retractors

- •3.2 Elevators, Luxators, and Periotomes

- •3.3 Dental Extraction Forceps

- •3.4 Ancillary Soft Tissue Instruments

- •3.5 Suturing Instruments

- •3.6 Surgical Suction

- •3.7 Surgical Handpiece and Bur

- •3.8 Surgical Irrigation Systems

- •3.9 Mouth Props

- •4.1 Maxillary Incisors

- •4.2 Maxillary Canines

- •4.3 Maxillary Premolars

- •4.4 Maxillary First and Second Molars

- •4.5 Mandibular Incisors

- •4.6 Mandibular Canines and Premolars

- •4.7 Mandibular Molars

- •5.3 Common Soft Tissue Flaps for Dental Extraction

- •5.4 Bone Removal

- •5.5 Tooth Sectioning

- •5.6 Cleanup and Closure

- •6.2 Damage to Adjacent Teeth or Restorations

- •7.4.1.1 Erupted

- •7.4.1.2 Unerupted/Partially Erupted

- •7.4.2 Mandibular Third Molars

- •7.4.2.1 Mesioangular

- •7.4.2.2 Distoangular/Vertical

- •7.4.2.3 Horizontal

- •7.4.2.4 Full Bony Impaction (Early Root Development)

- •8.1 Ischaemic Cardiovascular Disease

- •8.5 Diabetes Mellitus

- •8.6.1 Bleeding Diatheses

- •8.6.2 Medications

- •8.6.2.1 Management of Antiplatelet Agents Prior to Dentoalveolar Surgery

- •8.6.2.2 Management of Patients Taking Warfarin Prior to Dentoalveolar Surgery

- •8.6.2.3 Management of Patients Taking Direct Anticoagulant Agents Prior to Dentoalveolar Surgery

- •8.8 The Irradiated Patient

- •8.8.1 Management of the Patient with a History of Head and Neck Radiotherapy

- •9.5.1 Alveolar Osteitis

- •9.5.2 Acute Facial Abscess

- •9.5.3 Postoperative Haemorrhage

- •9.5.4 Temporomandibular Joint Disorder

- •9.5.5 Epulis Granulomatosa

- •9.5.6 Nerve Injury

- •B.1.3 Consent

- •B.1.4 Local Anaesthetic

- •B.1.5 Use of Sedation

- •B.1.6 Extraction Technique

- •B.1.7 Outcomes Following Extraction

- •B.2.1 Deciduous Incisors and Canines

- •B.2.2 Deciduous Molars

- •Bibliography

- •Index

2.5 Basi Ora l Anaesthes Technique 19

2.4 Side Effects and Toxicity

In general, local anaesthetics are safe when used correctly. However, as with the administration of any pharmacological substance, there are risks that need to be considered and minimised.

2.4.1 Local Risks

A number of risks are inherently involved with the manipulation of deep-tissue planes and the injection of pharmacologically active substances into tissue spaces:

●●Neuralgic-type pain from needle contact directly against a nerve trunk.

●●Haematoma in the tissue space, resulting in trismus, pain, or visible bruising.

●●Transient or permanent nerve injury from physical trauma or neurotoxicity of the anaesthetic agent.

●●Needle breakage, leading to foreign-body complications.

●●Transient facial paralysis due to the effect of anaesthetic on branches of the facial nerve.

●●Necrotizing sialometaplasia, a rare ischaemic tissue reaction in response to trauma.

2.4.2 Systemic Risks

Systemic toxicity may occur after administration of local anaesthetic, particularly in paediatric or elderly populations. The risk is higher after inadvertent intravascular administration; a negative aspirate helps to reduce this risk. The initial signs are often related to the central nervous system, and include anxiety, dizziness, restlessness, tinnitus, and diplopia. If not recognised early, the patient may develop tremors, convulsions, and loss of consciousness. Late signs are related to cardiotoxicity, and include bradycardia, cardiovascular collapse, and cardiac arrest.

True allergic reactions to local anaesthetic are rare. Patients may report an ‘allergy’ after experiencing tachycardia or palpitations following administration of a local anaesthetic containing adrenaline, when in fact this is a normal physiologic response to the injection of vasoconstrictive medications. Patients may also be allergic to preservatives, or to latex in the bung of the cartridge. When a patient reports a previous adverse or allergic reaction, it is important to elicit the details to determine if it was a true allergy, which would involve rash, urticaria, oedema, and anaphylaxis. Ester local anaesthetic agents have a higher rate of allergic reaction than amide anaesthetic agents, attributed to a metabolite produced from degradation of the anaesthetic agent, p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA). Patients with sulphur allergies may experience a reaction to the metabisulphite additive used to stabilise adrenaline in solution.

2.5Basic Oral Anaesthesia Techniques

Broadly, local anaesthetic techniques involving the oral cavity can be categorised into either infil- tration-based techniques or regional nerve block techniques. Infiltration anaesthesia involves the injection of local anaesthetic agent directly adjacent to the surgical site, relying on diffusion of anaesthetic around small nerve branches and endings which supply the region to produce anaesthesia. Regional nerve block involves the injection of a local anaesthetic agent distant to the surgical site, around the known position of a larger nerve bundle that supplies the area. Regional nerve blocks can be used to anaesthetise the inferior alveolar nerve, including lingual branches, the long buccal nerve, the greater palatine, and nasopalatine nerves. Whilst a nerve block can be technically

https://t.me/DentalBooksWorld

20 2 Local Anaesthesia

more challenging, as it relies on anatomic knowledge of nerve pathways in the head and neck, if performed correctly it can provide profound anaesthesia to larger anatomic areas with fewer injections, less local anaesthetic, and less patient discomfort.

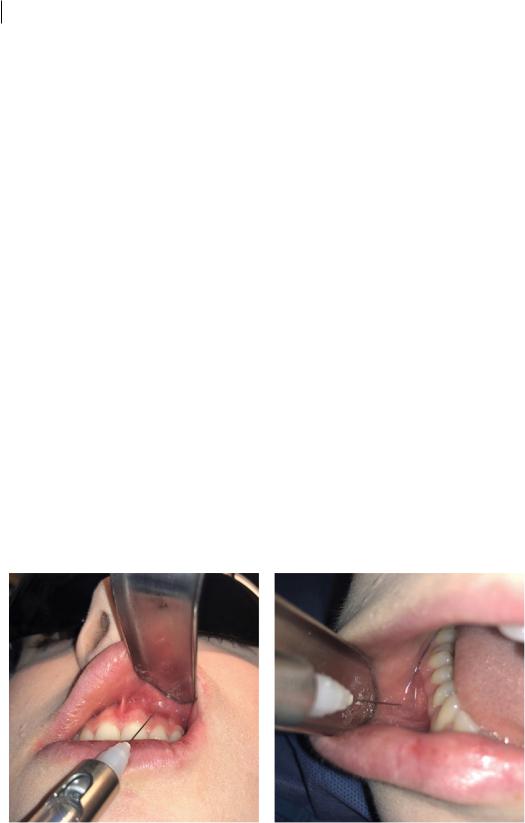

2.5.1Buccal Infiltration Anaesthetic

Buccal infiltration is a versatile technique that can be used to anaesthetise the maxillary dentition, the anterior mandible dentition, and the posterior mandible buccal mucosa (Figure 2.3). In anatomic areas where bone is thin and porous (e.g. anterior mandibular teeth or maxillary teeth), local anaesthetic solutions can diffuse through to the periodontium and tooth root apices, producing anaesthesia of the tooth itself. However, this technique does not adequately anaesthetise palatal or lingual tissues, which will need separate anaesthetic procedures prior to dental extraction. It likewise does not produce anaesthesia of the teeth or periodontal ligaments in the posterior mandible, due to the thick mandibular bony cortex; inferior alveolar nerve blocks will thus also be required.

1)Position the patient appropriately to ensure adequate access and lighting.

2)Retract the labial or buccal mucosa with a Minnesota retractor (or mouth mirror). Ensure adequate visualisation of attached and free gingiva. Keep the soft tissues taut to reduce patient discomfort.

3)Insert the needle into the deepest part of the vestibular sulcus in the buccal vestibule, and advance it approximately 2–3 mm, aiming for the approximate depth of the root apex but no further.

4)Aspirate the syringe to ensure the needle point has not traversed the intravascular space of a blood vessel.

5)Slowly inject the anaesthetic solution. A slow rate of injection will significantly reduce patient discomfort and pain.

6)Allow the local anaesthetic sufficient time to anaesthetise the tissues, based upon the pharmacokinetic properties of the anaesthetic solution, and monitor the patient for any adverse reaction.

Whilst infiltration anaesthesia is generally very safe, consideration should be given to regional structures. Insertion of the infiltration needle too deep into the maxillary vestibule can result in an unfortunate encounter with the orbit and its contents, whilst insertion too deep into the

Figure 2.3 Buccal/labial infiltration anaesthesia of the maxilla (left) and mandible (right).

https://t.me/DentalBooksWorld