Крючков Фундаменталс оф Нуцлеар Материалс Пхысицал Протецтион 2011

.pdfSpread of nuclear technologies in the 1950s–1960s g rew to cause concern of the international community about possible global sprawl of nuclear weapons. Many countries were ready to give up production of their own nuclear weapons, provided that other states – t heir neighbors first of all – would undertake similar commitments. Under th ese circumstances, Ireland put forward a Draft UN Resolution on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. In 1961, the General Assembly of the UNO unanimously adopted the proposed resolution, urging all countries to stand up against proliferation of nuclear weapons in the world. The appearance of this resolution showed that the international community was aware of the need for a global agreement on non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. However, 9 years passed before the resolution was legally acted upon in the form of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (1970).

In the 1960s, the global community took a number of steps towards curbing the spread of nuclear weapons and strengthening the control over the use of nuclear materials. The year 1963 saw conclusion of the agreement on banning nuclear tests on the ground and in the atmosphere. This instrument crowned the struggle against arms race by proving its worth as an efficient tool of halting NW spread to non-nuclear-weapons states.

The nuclear threat that loomed over the world during the Caribbean Crisis (Cuban Missile Crisis) prompted states of the Central and South America to set up a nuclear-weapons-free zone. The Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean (Tlatelolko Treaty signed in 1967) bans not only purchase and development of nuclear weapons in this region but also NW disposition there by foreign countries.

The problem of nuclear weapons proliferation was first identified at the UNO level by Ireland in 1958. In the mid-1960s, the United States and the Soviet Union started active discussions on issues associated with the prospective non-proliferation agreement which could become a framework for an international regime. In the long run, those negotiations resulted in conclusion of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which became effective in 1970. The Treaty shifted the postulates of the free nuclear trade epoch towards specific and firm commitments in regard to NM uses.

The main achievement of the NPT lies in the fact that the overwhelming majority of countries officially relinquished development and purchase of nuclear weapons. The only states that refrained from

11

joining the treaty were India, Pakistan, Israel, and Cuba. That is why the NPT, as a universal agreement, serves as a legal framework for implementation of international non-proliferation safeguards. The Treaty became an instrument whereby non-proliferation rules and standards found their way into international as well as national activities.

Starting with its effective date (March 1970), the NPT has been playing a key role in curbing the spread of nuclear weapons. It is the main international instrument that is making the international non-proliferation regime increasingly weighty and far-reaching. Its main provisions will be briefly addressed below.

The first two articles of the Treaty are of key importance, defining the main obligations of nuclear-weapons and non-nuclear-weapons states. It is stipulated there that nuclear states shall not sell nuclear weapons and nuclear explosive devices and shall execute control over them, while nonnuclear states shall not purchase or produce them.

In their negotiations, the signatories to the NPT were guided by the principle that adherence to the Treaty on the territories of non-nuclear states shall be monitored. This stipulation is addressed in Article III.1 of the NPT. The most important provision of this article is that the international safeguards shall apply to all nuclear materials handled in all peaceful nuclear activities of a country within its territory, under its jurisdiction or under its control, whichever is applicable.

In its second part, Article III of the NPT calls upon non-nuclear countries to accept the international safeguards for imported nuclear materials and components, whereby the IAEA safeguards can be extended. In fact, Article III.2 provides an international legal framework for the whole system of control over nuclear export.

Article IV deals with peaceful uses of nuclear energy. The developing knowledge of nuclear energy can serve both peaceful and military purposes. Therefore, the parties to the Treaty undertake to ensure that peaceful nuclear energy uses meet the relevant non-proliferation requirements (of Articles I and II).

Article V is related to peaceful nuclear explosions. It was included in the Treaty on the initiative of Mexico. Essentially, this article says that nuclear states may provide services to non-nuclear states in conducting peaceful nuclear explosions (PNE) under international supervision. Nevertheless, none of the non-nuclear states has so far made an official request for PNE services. This may be largely explained by the fact that

12

such explosions pose a certain risk to the environment while not being particularly needed.

Delegations of Egypt and Mexico proposed adding to the Treaty a special article on nuclear disarmament. But the question of how clear and firm were the obligations undertaken by nuclear states in accordance with Article VI, is still a point of sharp disagreement and debate. Many nonnuclear countries believe that the Treaty provisions concerning negotiations for effective measures to stop the nuclear arms race have not been met in a satisfactory way.

Article VII deals with nuclear-weapons-free zones (NWFZ). It acknowledges the right of states to set up regional NWFZs. In such a zone, it is forbidden not only to produce, purchase or receive nuclear weapons by non-nuclear parties, but also to store NW owned by nuclear states.

In 1995, a conference was held to discuss NPT prolongation, as the term of the Treaty was expiring. The main result of the conference work was its legally binding resolution on indefinite extension of the NPT. On the other hand, the conference participants voiced their concern about some outstanding problems, with the Treaty universality issues being among them.

It is common knowledge that the non-proliferation regime relies on a number of international arrangements and organizations involving both nuclear and non-nuclear states. This regime is embodied in interrelated international agreements, with the central place among them belonging to the NPT. Other relevant instruments include:

∙safeguards agreements; IAEA Statute; conventions under the aegis of the Agency, etc.;

∙national legislation regulating nuclear activities in the membercountries;

∙relevant Russian–American agreements in the field o f nuclear arms reduction;

∙agreements on establishment of nuclear-weapons-free zones: Tlatelolko, Rarotonga, Pelindaba and Bangkok treaties.

A whole number of international organizations are essential to the nonproliferation regime. So, an important role belongs to the International Atomic Energy Agency. Using a special system of measures – referred to as the IAEA Safeguards – the Agency monitors the si tuation trying to prevent NM diversion for purposes other than peaceful uses.

A sizeable contribution to solution of the proliferation problem is made by international export control (EC) regimes. The key instruments of export

13

control are restrictions on transfer of materials, equipment and technologies included in special check lists. Every country participating in the regime of export control is:

∙to create a national legal framework consistent with the agreements concluded;

∙to adhere to the EC principles in pursuing its national policy;

∙to participate in forums of the member–countries.

In the nuclear sphere, there are two main regimes for controlling export

of materials, equipment and technologies – one impl emented by the Zangger Committee and the other, by the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG). On the whole, however, the international system for control over export of mass destruction weapons includes the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), the Australian Group (for chemical and biological products and technologies), and the Wassenaar agreements (for conventional arms, dualpurpose products and technologies).

1.2. Some current problems of non-proliferation

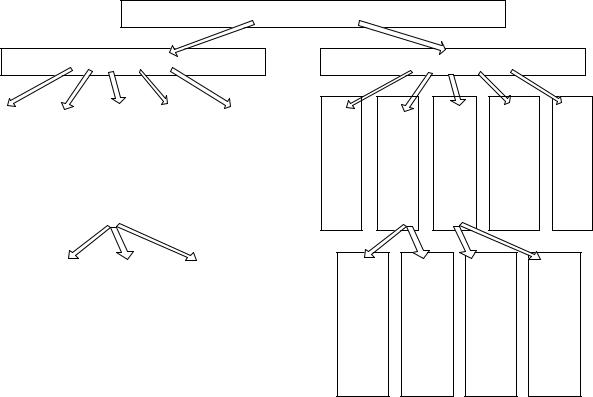

Concern over possible non-peaceful uses of nuclear materials has long been expressed by the world public opinion. Unfortunately, the weapons proliferation problem defies complete and final solution. Some of its ramifications are presented in Fig. 1.1. As the international nonproliferation regime took shape, part of these issues was settled in an acceptable way, while others still need adequate joint actions before they may be resolved. We shall dwell on some of them:

1. Extremely slow reduction of available nuclear arms is a serious problem for the non-proliferation regime. Non-nuclear-weapons countries tend to regard this fact as reluctance of nuclear states to take real, significant steps in this direction. Besides, the problem is complicated by the fact that nuclear arms reduction is an expensive process. Whatever the explanation, unceasing criticism has been directed against nuclear states, voiced during discussions of the Treaty results, for their being too slow in fulfilling their commitments on nuclear arms reduction.

14

Problems of the international non-proliferation regime

Traditional problems

Threshold states |

|

|

Safeguards |

|

|

|

Enhancement of IAEA Safeguards System |

|

|

Export control |

|

|

NW-free zones |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Extension of rights to and |

capabilities for NM inspection |

|

|

|

Improvement of inspection policy |

|

|

|

Provision of adequate financing |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New problems

Consequences of USSR breakup |

End of ‘cold war’ |

Nuclear arms reduction |

Illegal circulation of NM, dual-purpose technologies and materials |

De-facto appearance of new NW states |

Total ban of nuclear tests |

Ban of fissile material production |

Conversion of nuclear |

military complex |

Control over released weapons-grade materials |

Fig. 1.1. Some problems of the international non-proliferation regime

15

2.There are many countries today that have not joined the ranks of nuclear-weapons states. No wonder it is often hard to arrive at generally accepted decisions on further steps towards non-proliferation. To be more specific, a number of countries have their military nuclear programs but are not parties to the non-proliferation regime. Some of them, such as Israel, India and Pakistan, already have nuclear weapons in their possession, but refrain from their active deployment. Other states are, in a sense, ‘standing at the threshold’, as they initiated nuclear weapons programs in one way or another, but for some reason have stopped short at their production. Such states are Libya, Iran, North Korea, Brazil, and Argentina. Among the ‘threshold’ states, a special place belongs to the South African Republic, which built its own store of nuclear weapons but later – in 1990 – destroyed it. In most cases, an urge to possess nuclear weapons is caused by regional political problems between states and by the temptation of gaining a dominating role in the region.

It should not be forgotten that some countries (Japan, Germany, Sweden, Australia, etc.) are fully equipped economically and technically to produce nuclear weapons but are willingly committed to keep their nonnuclear status.

3.Breakup of the USSR in 1991 made an enormous impact on the global non-proliferation regime. The Soviet Union had always paid serious attention to safe use of nuclear materials, with the system of appropriate measures fairly well provided. But the methods used to this end were those of a totalitarian state, which was the owner of nuclear materials; and inside the state, such materials had practically no commercial value. The state set up a regime of secrecy and discipline, with all instructions strictly followed and failure to do so seriously punished.

The situation changed drastically after the USSR collapsed and reforms were launched in the country.

Firstly, the Soviet nuclear economy ceased to be an integral entity. The smoothly running system of interfacing and cooperation between Minsredmash (the predecessor of Minatom) enterprises was largely destroyed.

Secondly, the commercial value of nuclear materials became obvious. Thirdly, the national borders became more easily penetrable, providing

greater possibilities for smuggling or uncontrolled import/export of nuclear materials. This gave rise to the problem of illicit NM circulation, casing the need for tighter control over export of nuclear materials and dual-purpose products, as well as improved customs procedures.

16

Finally, the very approach to NM security was lop-sided. Nuclear centers were protected mostly against external intrusion. Today, nuclear materials need protection from both outsiders and insiders.

All the above circumstances called for serious revision of the attitude towards NM management, ie. towards its accounting, control and physical protection. This book will deal primarily with various aspects of these three components in management of nuclear material.

Distribution of the nuclear industry potential in the USSR

In 1991, the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in breakup of its formerly huge nuclear economy (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Nuclear industry potential at the time of the USSR collapse

|

Russia |

Ukraine |

Belarus |

Kazakhstan |

Central Asia |

TransCaucasian republics |

Baltic republics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nuclear weapons |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

|

Ship-borne nuclear |

100 % |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

power systems |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Nuclear power |

28 |

14 |

– |

1 |

– |

2 |

2 |

|

units (GW) |

(20.2) |

(12.9) |

|

(0.3) |

|

(0.8) |

(3.0) |

|

Research reactors |

25 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Uranium mining |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and primary |

40% |

20% |

– |

10% |

30% |

– |

– |

|

processing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UO2 production |

|

|

|

>80% |

|

|

|

|

Uranium |

100 % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

enrichment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Irradiated fuel |

100 % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

reprocessing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Soviet Union had signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty. When it ceased to exist, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan were left with nuclear weapons in their possession. The question was whether this amounted to appearance of new nuclear-weapons states.

17

In this situation, the whole world community and, first of all, Russia made enormous efforts to prevent nuclear weapons from sprawling into several countries and jeopardizing the regime of non-proliferation.

Russia removed all nuclear weapons from the territories of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine. Today, all nuclear arms of the former USSR are kept within Russian borders.

As a result, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan and all other ex-Soviet republics joined the NPT. The situation was rectified, and Russia succeeded to the Soviet Union as a party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Ship-borne nuclear power systems – carried first of all by submarines as well as by other vessels with nuclear reactors – are all found in Russia (the latter, e.g., belonging to the Murmansk Shipping Company).

As regards nuclear power plants, in 1991, Russia was left with 29 power units whose total capacity was 21.2 GW(e). Ukraine had 14 power units totaling 12.9 GW, while Kazakhstan owned one nuclear power plant with a 350 MW(e) fast neutron reactor BN–350. Part of the energy generated by the BN was used for desalination of seawater. BN–350 was shut down and is awaiting dismantling.

In Transcaucasia, only Armenia has a nuclear power plant consisting of two VVER–440 reactors. In 1989, the plant was close d down in reaction to popular anti-nuclear sentiments as well as for reasons of safety, considering that the plant was sited in a region of high seismic activity. Later, however, after the alarming energy crisis of 1992–1995, it w as decided to restart the reactors. The government of Armenia appealed to Russian Minatom for restoration of the NPP, as some of its equipment had gone into a bad state of repair over the time of its disuse. One power unit was successfully restarted and by 1999, the NPP was supplying 36 % of all electricity generated in this country.

In Lithuania, Minatom built the Ignalina NPP with its two RBMK-1500 power units. Both units are shut down today.

Uranium mining may be pointed out among the Nuclear Fuel Cycle (NFC) stages listed in Table 1.1. It is only 40 % of all uranium mines that are found in Russia, Ukraine accounting for 20 %, Kazakhstan for 10 %, and Tajikistan, Kirghizia and Uzbekistan for 30 %.

It is an important fact that the most hazardous – f rom the viewpoint of proliferation resistance – NFC capabilities are all sited in Russia. These are uranium enrichment, reprocessing and plutonium separation facilities.

18

References

1.Ядерное нераспространение / Под общ. ред. В.А. Орлова. М.: ПИР Центр, 2002.

2.Гарднер Г.Т. Ядерное нераспространение. М.: МИФИ, 1995.

3.Тимербаев Р.М. Россия и ядерное нераспространение. М.: Наука,

1999.

19

CHAPTER 2

MAIN TECHNOLOGIES OF THE PRESENT-DAY NUCLEAR FUEL CYCLE AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE NONPROLIFERATION REGIME*

Nuclear material (NM) is essential for two self-sustaining nuclear reactions which are accompanied by liberation of large energy amounts, namely:

∙chain fission reaction involving heavy nuclei. The nuclear material in this reaction includes natural isotopes of uranium and thorium, man-made

transuranic isotopes – mainly those of plutonium, a s well as of neptunium, americium, curium, berkelium, and californium, and the man-made 233U, which can be produced by exposure of thorium to neutron radiation;

∙thermonuclear fusion reaction involving nuclei of light isotopes. The nuclear material here includes hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and tritium). Natural hydrogen comprises 0.015 % of deuterium and none of tritium. Other nuclear materials are heavy water (D2O) and lithium whose

isotope 6Li is capable of vigorously producing tritium in the reaction 6Li(n,α)T.

Thus, nuclear materials are:

∙feed materials – uranium and thorium ores, natural uranium and thorium, depleted uranium (with low content of 235U);

∙special materials – enriched uranium (with high con tent of 235U), plutonium, and 233U;

∙transuranic elements – Np, Am, Cm, Bk, Cf;

∙heavy water, deuterium, tritium, lithium. Nuclear technologies include:

∙NM production;

∙NM storage, transportation and use;

∙NM reprocessing and recycling;

∙radioactive waste treatment and disposal.

Nuclear technologies and safe NM management are interrelated. The term “safety” – taken broadly – implies radiation s afety, nuclear safety, etc. In terms of non-proliferation, it means security from NM theft or diversion for production of nuclear explosives or other illicit uses.

* This chapter was prepared with the help of V.A. Apse and A.N. Shmelyov, based on the book by V.A. Apse and A.N. Shmelyov “Nuclear Technologies”. M.: MIFI, 2001.

20