- •Главная

- •1.1 Напряжений и концентраторы

- •1.1.3 Концентраторы напряжения

- •1.3 Stress concentration factor

- •1.7 Elastic-plastic stress concentration

- •1.8 Joints: bolts and welds

- •3. Механические свойства конструкционных материалов

- •3.1 Напряженности испытания

- •3.2 Stress - strain diagram

- •3.3 Testing schemes

- •3.4 Strength

- •4 Прочность материалов

- •4.1 Tension and compression

- •4.2 Shear and torsion

- •4.3 Stress-strain state

- •4.4 Bending: force and moment diagrams

- •4.5 Geometrical characteristics of sections

- •4.6 Bending: stress and deformation

- •4.7 Mixed mode loading

- •4.8 Buckling

- •4.9 Statically indeterminate systems

- •4.10 Three-dimensional structures

- •References

- •5. Theory of elasticity

- •5.1 Deformation

- •5.2 Stress

- •5.3 Hooke's law

- •5.4 Plane problems

- •5.5 Torsion

- •5.6 Bending

- •5.7 Polar coordinates

- •5.8 Plates

- •5.9 Shells

- •5.10 Contact stresses

- •6.2 Distribution functions

- •6.3 Structural models of reliability

- •6.4 Limiting state

- •6.5 Dispersion

- •6.6 Durabilty

- •6.7 Design by reliability criterion

- •6.8 Risk

- •6.9 Safety classes

- •6.10 Risk : structural and social

- •References

- •7 Materials science

- •7.1 Crystalline solids

- •7.2 Mechanical properties

- •7.3 Failure

- •7.4 Phase diagrams

- •7.5 Heat treatment of metals and alloys

- •7.6 Corrosion of metals and alloys

- •7.7 Casting

- •7.8 Polymers

- •7.9 Composites

- •7.10 Forming of metals

- •8.2 Mechanical properties

- •8.3 Stress concentration

- •8.4 Defects

- •8.5 Residual Stress

- •8.6 Strength

- •8.7 Fatigue strength

- •8.8 Fracture

- •8.9 Weldability

- •References

- •9 Composites

- •9.1 Structure of composites

- •9.2 Fibers

- •9.3 Rigidity

- •9.4 Strength

- •9.5 Crack resistance

- •9.6 Optimization

- •9.7 Fatigue and temperature effect

- •9.8 Reliability

- •9.9 Joints

- •9.10 Material selection

- •References

- •10 Finite element analysis

- •10.1 Finite element method

- •10.2 Finite elements

- •10.3 Meshing

- •10.4 Boundary conditions

- •10.5 Deformation

- •10.6 Accuracy

- •10.7 Heat transfer analysis

- •10.8 Dynamics

- •10.9 Computational fluid dynamics

- •10.10 Design analysis

- •References

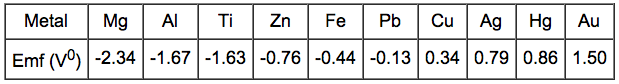

7.6 Corrosion of metals and alloys

The

electrochemical series ranks the general resistance of metals to

corrosion. The more negative the standard Emf (Electromotive force)

potential, the more easily the material will oxidize.

The

monocrystal structure shows a higher resistance to corrosion than the

same metal with polycrystalline structure. The smaller the size of

grains, the more the material is prone to corrosion damages.

If

two metals are electrically connected and immersed in a solution of

their own ions the EMF potential determines which material will

corrode. Iron dissolves in the electrolyte because iron has electrode

potential (-0.44 V) lower than that of copper (0.33 V). Consquently,

the copper deposits on the cathode. The magnitude of the voltage

driving the dissolution of iron is found to be:

If

two metals are electrically connected and immersed in a solution of

their own ions the EMF potential determines which material will

corrode. Iron dissolves in the electrolyte because iron has electrode

potential (-0.44 V) lower than that of copper (0.33 V). Consquently,

the copper deposits on the cathode. The magnitude of the voltage

driving the dissolution of iron is found to be:

DV = V1 - V2 = 0.34 - (-0.44) = 0.78 V

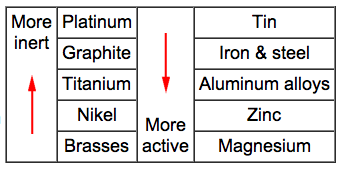

Galvanic

corrosion occurs when dissimilar metals are placed in assembly within

a corrosive electrolyte (e.g. sea water). This results in one of the

metals becoming anodic and corroding at faster rate than normal. The

other metal is the cathode responds with a decrease in corrosion

rate. The Galvanic series is useful for selecting materials to be

joined. Materials towards the bottom of the table are more active

(anodic) and will corrode at a faster rate than those above them. In

addition, the closer two metals are in the table the weaker the

corroding effect.

Galvanic

corrosion occurs when dissimilar metals are placed in assembly within

a corrosive electrolyte (e.g. sea water). This results in one of the

metals becoming anodic and corroding at faster rate than normal. The

other metal is the cathode responds with a decrease in corrosion

rate. The Galvanic series is useful for selecting materials to be

joined. Materials towards the bottom of the table are more active

(anodic) and will corrode at a faster rate than those above them. In

addition, the closer two metals are in the table the weaker the

corroding effect.

Corrosion

rate depends on the relative areas of the anode and cathode. When the

surface area of the anodic metal is smaller than that of the cathode

the resulting corrosion is rapid. Consequently, the corrosion rate is

slow when a larger anode is connected to a small cathode.

Corrosion

rate depends on the relative areas of the anode and cathode. When the

surface area of the anodic metal is smaller than that of the cathode

the resulting corrosion is rapid. Consequently, the corrosion rate is

slow when a larger anode is connected to a small cathode.

The

bolt displayed under a constant load will corrode at a greater rate

than one that is unloaded. This is due to regions of a high local

stress being anodic to those of a lower stress. The combined action

of a sufficient applied tensile stress and an aggressive environment

can cause the cracking of a part.

The

bolt displayed under a constant load will corrode at a greater rate

than one that is unloaded. This is due to regions of a high local

stress being anodic to those of a lower stress. The combined action

of a sufficient applied tensile stress and an aggressive environment

can cause the cracking of a part.

Areas

of metals subjected to cold working are rich in dislocations and

therefore constantly under stress. This results in them being anodic

to the less stressed regions and accelerates corrosion.

Areas

of metals subjected to cold working are rich in dislocations and

therefore constantly under stress. This results in them being anodic

to the less stressed regions and accelerates corrosion.

The

flow of oxygen to the area under the gasket is restricted and

therefore its concentration is low. This area will be anodic and

corrode faster than the oxygen rich areas.

The

flow of oxygen to the area under the gasket is restricted and

therefore its concentration is low. This area will be anodic and

corrode faster than the oxygen rich areas.

For

a given fatigue life the influence of a corrosive environment on the

fatigue strength of metals increases if the frequency decreases. This

means that a structure loaded at a lower frequency will sustain less

cycles to fracture at a given applied stress. The picture shows S-N

curves of carbon steel tested in several mediums. All metals and

alloys cyclically loaded under a corrosive environment do not exhibit

a endurance (fatigue) limit. Which means that a structure exploited

under such conditions will finally break even if applied stress is

very low.

For

a given fatigue life the influence of a corrosive environment on the

fatigue strength of metals increases if the frequency decreases. This

means that a structure loaded at a lower frequency will sustain less

cycles to fracture at a given applied stress. The picture shows S-N

curves of carbon steel tested in several mediums. All metals and

alloys cyclically loaded under a corrosive environment do not exhibit

a endurance (fatigue) limit. Which means that a structure exploited

under such conditions will finally break even if applied stress is

very low.

7.7 Casting

The

typical structure of a cast alloy consists of three zones:

1.

Chill zone - a few layers of fine equiaxed grains near the mold

walls.

2. Columnar zone - oriented grains grown in the direction

opposite of the heat transfer through the mold.

3. Equiaxed

zone - equiaxed grains of large size at the center of the

casting.

Depending on the processing conditions and material the

proportion of the columnar and equiaxed zones can be altered. Slow

cooling, adding the nucleating agents and agitating the melt

contribute to the growth of equiaxed zone. The enlarged columnar zone

is peculiar for pure metals.

The

typical structure of a cast alloy consists of three zones:

1.

Chill zone - a few layers of fine equiaxed grains near the mold

walls.

2. Columnar zone - oriented grains grown in the direction

opposite of the heat transfer through the mold.

3. Equiaxed

zone - equiaxed grains of large size at the center of the

casting.

Depending on the processing conditions and material the

proportion of the columnar and equiaxed zones can be altered. Slow

cooling, adding the nucleating agents and agitating the melt

contribute to the growth of equiaxed zone. The enlarged columnar zone

is peculiar for pure metals.

The

greater the volume to surface area ratio, the slower a solid body

cools and solidifies.

Solidification time can be estimated by

Chvorinov's rule:

The

greater the volume to surface area ratio, the slower a solid body

cools and solidifies.

Solidification time can be estimated by

Chvorinov's rule:

TS = B(V/A)2,

where

V is the volume; A is the surface area; B is an empirical

constant.

Patterns

very often have a temper on the vertical surfaces parallel to the

direction of withdrawal. This allows for an easy removal of the

pattern from the mold without any distortion or breaking of the mold

cavity. The angle of draft is normally 0.5-2o.

The angle depends mainly on the materials and processing

conditions.

Patterns

very often have a temper on the vertical surfaces parallel to the

direction of withdrawal. This allows for an easy removal of the

pattern from the mold without any distortion or breaking of the mold

cavity. The angle of draft is normally 0.5-2o.

The angle depends mainly on the materials and processing

conditions.

Materials

with a short temperature range of crystallization (eg. pure metals or

eutectic alloys) tend to form a large concentrated shrinkage cavity

(right). The castings of alloys with a large freezing range have

porosity dispersed in the bulk of the material (left).

Materials

with a short temperature range of crystallization (eg. pure metals or

eutectic alloys) tend to form a large concentrated shrinkage cavity

(right). The castings of alloys with a large freezing range have

porosity dispersed in the bulk of the material (left).

The

fluidity is the capability of material to flow into mold cavities

prior to solidification. The fluidity of pure metals and eutectic

alloys is higher than that of hypoeutectoid or hypereutectoid

alloys.

The

fluidity is the capability of material to flow into mold cavities

prior to solidification. The fluidity of pure metals and eutectic

alloys is higher than that of hypoeutectoid or hypereutectoid

alloys.

Risers

are used to compensate for the shrinkage of molten metal during

solidification and to avoid the formation of a shrinkage cavity

within the casting. The shrinkage cavity forms into the riser because

it is the last part solidified in the mold. The risers are usually

located over the center of the heaviest sections of castings.

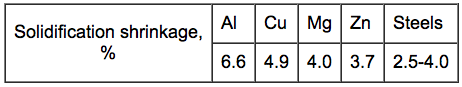

The

riser must be large enough to feed the shrinkage in the casting.

Solidification shrinkage varies for different metals and

influences the size of the risers.

Risers

are used to compensate for the shrinkage of molten metal during

solidification and to avoid the formation of a shrinkage cavity

within the casting. The shrinkage cavity forms into the riser because

it is the last part solidified in the mold. The risers are usually

located over the center of the heaviest sections of castings.

The

riser must be large enough to feed the shrinkage in the casting.

Solidification shrinkage varies for different metals and

influences the size of the risers.

Permanent mold casting vs Sand casting:

Increased dimensional accuracy and smoother surfaces; A new mold to produce every part is avoided; Increased mechanical properties due to a fine grain structure; Less time to cast a part; Shape and size of castings are limited; Not suitable for metals with a low fluidity.