aswath_damodaran-investment_philosophies_2012

.pdf

520 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

of being wrong on market direction. With futures contracts, that cost can be large and unpredictable since you have to cover future price movements in the wrong direction. With options contracts, the cost is limited to the price you paid for the options if you are a call buyer. However, the trade-off is that a futures contract is essentially costless, though you are required to put up a margin to ensure that you honor the contract. Buying a call or a put option will cost you, with the cost increasing as a function of the volatility of the underlying index of asset class.

So, assuming that you are bullish about a market, should you buy futures or call options? Conversely, if you are bearish, should you sell futures or buy put options? To make that decision, you have to consider two factors. The first is the degree of certainty you possess about your market timing abilities: the more certain you feel, the greater the payoff to using futures instead of options. The second factor is the price you are paying for the downside protection on options. If you feel that options are overpriced (i.e., that the implied volatility in the options is much higher than the true volatility), you will be more likely to use futures contracts.

E x c h a n g e - T r a d e d F u n d s ( E T F s )

An exchange-traded fund is essentially what it claims to be, a market-traded security that tracks a market. It is generally created by a sponsor, who chooses both the index that the ETF will track and a method for tracking the index. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of ETFs increased from 80 to 923 and the amount invested in ETFs increased from $60 billion to more than a trillion. The first ETF, created in 1993, tracked the S&P 500, but you can now buy and sell ETFs on almost every asset class and subclass: sectors, commodities, global equities, fixed income.

Since ETFs can be used by market timers to make bets on the underlying markets, it is worth examining the trade-off on using ETFs instead of derivatives (futures or options). Like options contracts, ETFs offer you the benefits of knowing your costs with certainty at the time of the investment, though borrowing money to buy ETFs can make these costs uncertain. Like futures contracts, ETFs do not require you to pay a time premium to make a market bet. Unlike options or futures, which have finite lives, you can hold an ETF for any period you choose. Ultimately, the pricing of indexes, options, futures, and ETFs is all linked together by arbitrage, since you can create your own synthetic version of any of them by using the others. Consequently, it is unlikely that any of them is going to offer you an incredible bargain. The choice then has to be made on your comfort level with each alternative, the liquidity in each market, and your time horizon as an investor, with ETFs being more suited for investors who want to make longer-term bets.

The Impossible Dream? Timing the Market |

521 |

C O N N E C T I N G M A R K E T T I M I N G T O

S E C U R I T Y S E L E C T I O N

Can you be both a market timer and a stock picker? We don’t see why not, since they are not mutually exclusive philosophies. In fact, the same beliefs about markets that led you to become a security selector may also lead you to become a market timer. For example, if you believe that markets overreact to new information, you may buy stocks after big negative earnings surprises, but you may also buy the entire market after negative economic or employment reports. In fact, there are many investors who combine asset allocation and security selection in a coherent investment strategy.

There are, however, two caveats to an investment philosophy that includes this combination. First, to the extent that you have differing skills as a market timer and as a security selector, you have to gauge where your differential advantage lies, since you have limited time and resources to direct toward your task of building a portfolio. Second, you may find that your attempts at market timing are undercutting your stock picking and that your overall returns suffer as a consequence. If this is the case, you should abandon market timing and focus exclusively on security selection.

C O N C L U S I O N

Everyone wants to time markets, and it is not difficult to see the reasons for the allure. A successful market timer can deliver very high returns with relatively little effort. The cost of market timing, though, is high in terms of transaction costs (higher turnover ratios and tax bills) and opportunity costs (staying out of the market in years in which the market goes up). In fact, you need to be right about two-thirds of the time for market timing to pay off.

If you do decide to time markets, you have a wide range of market timing tools. Some are nonfinancial and range from the spurious like the Super Bowl indicator (whose correlation with the market is pure chance) to feel-good indicators (that measure the mood of people and thus the level of the market) to hype indicators (such as cocktail party chatter). Some market timing is centered around the macroeconomic variables that affect stock prices—interest rates and economic growth—with the intuitive argument that you buy stocks when interest rates are low and in advance of robust economic growth. While the intuition may be impeccable, markets are tough to time because they are based on predictions of these variables. Thus, high economic growth, by itself, may not lead to higher stock prices if the growth was less than anticipated. One way to incorporate forecasted growth and

522 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

risk into the analysis is to estimate the intrinsic value of the market; that is, value the market as the present value of the expected cash flows you would get from investing in it. While this may yield good long-term predictions, a better way of getting short-term predictions may be an assessment of the value of the market, relative to its own standing in prior years and to other markets.

While the menu may be varied when it comes market timing strategies, there is little evidence of actual market timing success, even when we focus on those who claim to have the most expertise at it. Collectively, mutual funds seem to exhibit reverse market timing skills at worst, and neutral market timing skills at best, switching out of stocks (and into cash) just before big up movements in the markets and doing the opposite before stock price declines. Even those mutual funds that market themselves as market timers—the tactical asset allocation funds—do not add any value from market timing. The asset allocation advice that comes from investment newsletters and market strategists also seems to suffer from the same problem of no payoffs.

If you believe that you are the exception to this general rule of failure and that you can time markets, you can do it with varying degrees of gusto. The simplest strategy is to alter your asset allocation mix to reflect your market views, but this may require you to be out of stocks for extended periods. If you want to be fully invested in equities, you can try to switch investment styles ahead of market moves, moving from value investing (in periods of high earnings growth) to growth investing (if growth levels off) or shift your money across sectors of the market. Finally, if you have enough faith in your market timing abilities to pull it off, you can buy undervalued and sell overvalued markets, and make significant profits when they converge. The risk, of course, is that they will diverge instead and that you will see your portfolio suffer as a consequence.

E X E R C I S E S

1.Do you think that you can time markets? It not, why not? If yes, why do you think that you can?

2.If you believe that you can time markets, try answering the following questions:

a.Is your market timing restricted to one market (say, the stock market) or do you use it across markets (commodities, bonds, currencies, etc.)?

b.What indicator or indicators do you use in determining that a market is mispriced? Why do you think it works?

The Impossible Dream? Timing the Market |

523 |

c.Are there any potential costs that you see from timing markets? If yes, how do you try to minimize these costs?

3.Assuming that you try to time markets, address the following:

a.Is your market timing long term or short term? Is it defensive (to protect against losses) or aggressive (to augment profits)?

b.Which market timing approach (asset allocation, speculation) do you use?

c.What market timing instruments (ETFs, derivatives) do you employ? Why?

4.Pick a market timer who is in the news right now (usually because the timer got the last market move right). What market timing indicator does he or she use to time markets? What track record does he or she have over the long term?

Lessons for Investors

To be a successful market timer, you have to:

Be right about two-thirds of the time: The payoff to timing markets correctly is high, but the cost of getting it wrong is also high. The payoff comes from staying out of the market in bad years, but the cost is that you may stay out of the market in good years.

Find an indicator that works consistently: There are dozens of indicators that are used to time markets, but few of them seem to work consistently over long periods. Even those that do only give you a sense of direction (up or down) but not of magnitude (how much up or how much down).

Recognize that you do not have many successful role models: Attempts at market timing on the part of professionals—money managers, investment newsletters, and market strategists—have generally failed. Most of them tend to follow markets rather than lead them.

526 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

A F u l l y I n d e x e d F u n d

A fully indexed fund is relatively simple to create once the index to be replicated has been identified. There are three steps in the process. The first step is to obtain information on what stocks (or assets) go into the index and their weights in the index. Note that weighting schemes vary widely across indexes. Some indexes weight stocks based on their market capitalizations (S&P 500), some are price weighted index (Dow 30), and some are based on market float (New York Stock Exchange Composite). There are even indexes where the weights are based on trading volume on the exchange. The second step is to invest the fund in each of the stocks in the index, in exactly the same proportions that they are weighted in the index. An index fund has to be fully invested in the index, since cash holdings can cause the fund’s returns to deviate from those of the index.

Once the index fund is created, there are two maintenance requirements. First, indexes change over time, as some firms are removed from the index due to acquisitions, due to bankruptcies, or because they no longer meet the criteria for the index, and new firms are added. As the index changes, the index fund will have to change as well—the deleted firms will have to be sold and the added firms will have to be acquired. While changes are relatively rare for well-established and mature indexes such as the S&P 500, they can be much more frequent for indexes that track changing or growing markets (as is the case with technology or emerging market indexes). The second requirement is that the weights in the fund will have to be monitored and adjusted to reflect changes in the weights of the ingredients of the index. One of the advantages of indexing a market-capitalization-weighted fund is that it is self-adjusting. In other words, if one stock doubles and another stock halves, the changes in their weighting in the index fund will mirror changes in the weighting in the index.

A S a m p l e d I n d e x F u n d

In some cases, it may not be practical to construct a fully indexed fund. If you are replicating an index that contains thousands of stocks, such as the Wilshire 5000 index or an index of illiquid assets or stocks, the transaction cost of creating and maintaining the index might be very large. One way around this problem is to create a fund that looks very much like the index but does not quite replicate this. You can accomplish this objective by sampling the index and buying some of the stocks listed in the index. Vanguard, which has long been the leader in the index fund business, uses sampling for its Total Market Fund that attempts to replicate the performance of all stocks traded in the United States, as well as its small stock and European index funds.

Ready to Give Up? The Allure of Indexing |

527 |

|

120.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

500 |

80.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with S&P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Correlation |

40.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20.00% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.00% |

|

|

|

|

300 |

350 |

400 |

450 |

500 |

|

50 |

100 |

150 |

200 |

250 |

Number of Stocks in Fund

F I G U R E 1 3 . 1 Correlation with the S&P 500 Index

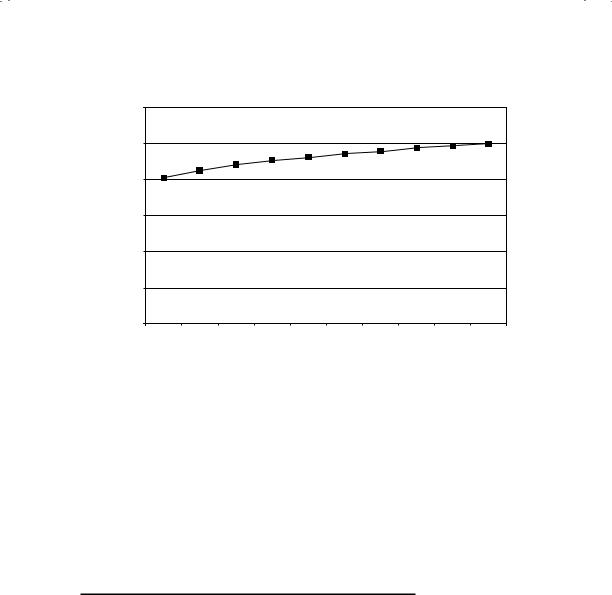

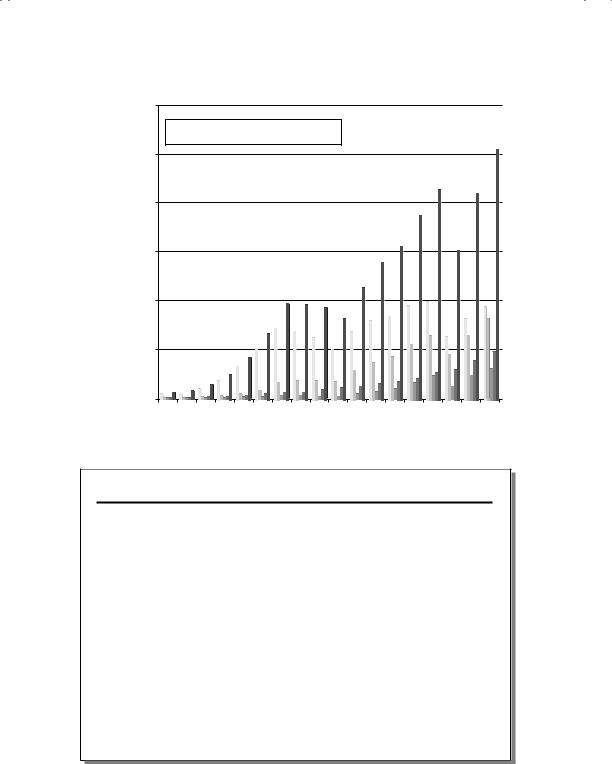

How close can you get to the index with a sampled index fund? One way to measure the closeness is to measure the correlation between an index fund and the index that it tracks. A fully indexed fund should have a correlation of 100 percent, but a sampled index fund can get very close even with a much smaller number of stocks. Figure 13.1 presents the correlation between a sampled index fund and the S&P 500 as a function of the number of stocks in the index fund.

Note that the correlation is fairly high even with 50 stocks and very quickly converges to 100 percent.

A H I S T O R Y O F I N D E X I N G

In many ways, index funds owe their existence to the early research done on efficient markets by academics. Prior to the 1960s, the conventional wisdom was that you entrusted your savings to money managers on Wall Street and they delivered high returns in exchange for management fees and transaction costs. No individual investor, it was believed, could compete against these professionals. As financial economics came into being as a discipline in the 1950s and 1960s, researchers increasingly found evidence to the contrary. In fact, the efficient market hypothesis, which argued that market prices were the best estimates of value and that all of the time and resources spent by money managers trying to pick stocks was in vain, acquired a strong following. While most practitioners remained resistant to

528 |

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHIES |

the notion that markets were efficient, there were some who saw opportunities in these academic findings. If diversification was the primary source of portfolio gains and picking stocks was not a fruitful exercise, why not create funds that were centered on diversification and minimize transaction costs? Indexing was initially made available to institutional investors in 1971, and soon individual investors were able to play the indexing game when the Vanguard 500 Index fund made its debut in 1976. Over the past three decades, it has grown to become the second largest equity fund in the world, with about $93 billion in assets in November 2011. Index funds have also widened their reach beyond the S&P 500, with 63 percent of all U.S. index funds invested in non–S&P 500 stocks, including other domestic equities (32 percent), global equities (13 percent), and bonds (19 percent) at the end of 2010.

In the past three decades, index funds have gradually increased their share of the overall market not only for individual investors’ savings but for pension and insurance money; the percentage of money invested in index funds, as a percentage of total money invested in mutual funds, has increased from 5.2 percent in 1995 to 14.5 percent in 2010; among just equity funds, index funds now account for almost 25 percent of invested money. This is not to suggest that index funds have not had their ebbs and flows. The initial impetus for index funds came from the abysmal returns delivered by portfolio managers in the 1970s. While many of these portfolio managers cannot be faulted for not seeing the long-running bear market and high inflation of the period, the subpar returns did draw attention to their management fees. Ever since, the growth of index funds seems to slow in boom periods (the early 1980s and the later 1990s), when it looks like active money management can pay off, and picks up again when markets stagnate or decline. Figure 13.2 graphs out the growth of index funds from 1993 to 2010, broken down by category.

The choices in index funds have proliferated, and you now see funds indexed to almost every conceivable index. For instance, Vanguard offered 48 index fund choices for investors in November 2011, with choices across capitalization (small-cap, mid-cap, and large-cap), return objective (dividends versus capital appreciation), style (value versus growth), global (domestic and international), and asset class (equities, bond, and balanced) funds. It even offers a social index fund, composed of mid-cap and large-cap companies that have been screened to meet social, human rights, and environmental criteria. Most of these funds are sampled funds rather than fully indexed funds, and some have restrictions on withdrawals. While we have used the Vanguard funds to illustrate the diversity of choices when it comes to index funds today, there are other fund families that also have started competing for this very large market.

S&P 500

S&P 500  Other Domestic Equity

Other Domestic Equity  Global

Global