- •CONTENTS

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction to Toxicology

- •1.1 Definition and Scope, Relationship to Other Sciences, and History

- •1.1.2 Relationship to Other Sciences

- •1.1.3 A Brief History of Toxicology

- •1.3 Sources of Toxic Compounds

- •1.3.1 Exposure Classes

- •1.3.2 Use Classes

- •1.4 Movement of Toxicants in the Environment

- •Suggested Reading

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Cell Culture Techniques

- •2.2.1 Suspension Cell Culture

- •2.2.2 Monolayer Cell Culture

- •2.2.3 Indicators of Toxicity in Cultured Cells

- •2.3 Molecular Techniques

- •2.3.1 Molecular Cloning

- •2.3.2 cDNA and Genomic Libraries

- •2.3.3 Northern and Southern Blot Analyses

- •2.3.4 Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

- •2.3.5 Evaluation of Gene Expression, Regulation, and Function

- •2.4 Immunochemical Techniques

- •Suggested Reading

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 General Policies Related to Analytical Laboratories

- •3.2.1 Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

- •3.2.2 QA/QC Manuals

- •3.2.3 Procedural Manuals

- •3.2.4 Analytical Methods Files

- •3.2.5 Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS)

- •3.3 Analytical Measurement System

- •3.3.1 Analytical Instrument Calibration

- •3.3.2 Quantitation Approaches and Techniques

- •3.4 Quality Assurance (QA) Procedures

- •3.5 Quality Control (QC) Procedures

- •3.6 Summary

- •Suggested Reading

- •4 Exposure Classes, Toxicants in Air, Water, Soil, Domestic and Occupational Settings

- •4.1 Air Pollutants

- •4.1.1 History

- •4.1.2 Types of Air Pollutants

- •4.1.3 Sources of Air Pollutants

- •4.1.4 Examples of Air Pollutants

- •4.1.5 Environmental Effects

- •4.2 Water and Soil Pollutants

- •4.2.1 Sources of Water and Soil Pollutants

- •4.2.2 Examples of Pollutants

- •4.3 Occupational Toxicants

- •4.3.1 Regulation of Exposure Levels

- •4.3.2 Routes of Exposure

- •4.3.3 Examples of Industrial Toxicants

- •Suggested Reading

- •5 Classes of Toxicants: Use Classes

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 Metals

- •5.2.1 History

- •5.2.2 Common Toxic Mechanisms and Sites of Action

- •5.2.3 Lead

- •5.2.4 Mercury

- •5.2.5 Cadmium

- •5.2.6 Chromium

- •5.2.7 Arsenic

- •5.2.8 Treatment of Metal Poisoning

- •5.3 Agricultural Chemicals (Pesticides)

- •5.3.1 Introduction

- •5.3.3 Organochlorine Insecticides

- •5.3.4 Organophosphorus Insecticides

- •5.3.5 Carbamate Insecticides

- •5.3.6 Botanical Insecticides

- •5.3.7 Pyrethroid Insecticides

- •5.3.8 New Insecticide Classes

- •5.3.9 Herbicides

- •5.3.10 Fungicides

- •5.3.11 Rodenticides

- •5.3.12 Fumigants

- •5.3.13 Conclusions

- •5.4 Food Additives and Contaminants

- •5.5 Toxins

- •5.5.1 History

- •5.5.2 Microbial Toxins

- •5.5.3 Mycotoxins

- •5.5.4 Algal Toxins

- •5.5.5 Plant Toxins

- •5.5.6 Animal Toxins

- •5.6 Solvents

- •5.7 Therapeutic Drugs

- •5.8 Drugs of Abuse

- •5.9 Combustion Products

- •5.10 Cosmetics

- •Suggested Reading

- •6 Absorption and Distribution of Toxicants

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Cell Membranes

- •6.3 Mechanisms of Transport

- •6.3.1 Passive Diffusion

- •6.4 Physicochemical Properties Relevant to Diffusion

- •6.4.1 Ionization

- •6.5 Routes of Absorption

- •6.5.1 Extent of Absorption

- •6.5.2 Gastrointestinal Absorption

- •6.5.3 Dermal Absorption

- •6.5.4 Respiratory Penetration

- •6.6 Toxicant Distribution

- •6.6.1 Physicochemical Properties and Protein Binding

- •6.7 Toxicokinetics

- •Suggested Reading

- •7 Metabolism of Toxicants

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Phase I Reactions

- •7.2.4 Nonmicrosomal Oxidations

- •7.2.5 Cooxidation by Cyclooxygenases

- •7.2.6 Reduction Reactions

- •7.2.7 Hydrolysis

- •7.2.8 Epoxide Hydration

- •7.2.9 DDT Dehydrochlorinase

- •7.3 Phase II Reactions

- •7.3.1 Glucuronide Conjugation

- •7.3.2 Glucoside Conjugation

- •7.3.3 Sulfate Conjugation

- •7.3.4 Methyltransferases

- •7.3.7 Acylation

- •7.3.8 Phosphate Conjugation

- •Suggested Reading

- •8 Reactive Metabolites

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 Activation Enzymes

- •8.3 Nature and Stability of Reactive Metabolites

- •8.4 Fate of Reactive Metabolites

- •8.4.1 Binding to Cellular Macromolecules

- •8.4.2 Lipid Peroxidation

- •8.4.3 Trapping and Removal: Role of Glutathione

- •8.5 Factors Affecting Toxicity of Reactive Metabolites

- •8.5.1 Levels of Activating Enzymes

- •8.5.2 Levels of Conjugating Enzymes

- •8.5.3 Levels of Cofactors or Conjugating Chemicals

- •8.6 Examples of Activating Reactions

- •8.6.1 Parathion

- •8.6.2 Vinyl Chloride

- •8.6.3 Methanol

- •8.6.5 Carbon Tetrachloride

- •8.6.8 Acetaminophen

- •8.6.9 Cycasin

- •8.7 Future Developments

- •Suggested Reading

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Nutritional Effects

- •9.2.1 Protein

- •9.2.2 Carbohydrates

- •9.2.3 Lipids

- •9.2.4 Micronutrients

- •9.2.5 Starvation and Dehydration

- •9.2.6 Nutritional Requirements in Xenobiotic Metabolism

- •9.3 Physiological Effects

- •9.3.1 Development

- •9.3.2 Gender Differences

- •9.3.3 Hormones

- •9.3.4 Pregnancy

- •9.3.5 Disease

- •9.3.6 Diurnal Rhythms

- •9.4 Comparative and Genetic Effects

- •9.4.1 Variations Among Taxonomic Groups

- •9.4.2 Selectivity

- •9.4.3 Genetic Differences

- •9.5 Chemical Effects

- •9.5.1 Inhibition

- •9.5.2 Induction

- •9.5.3 Biphasic Effects: Inhibition and Induction

- •9.6 Environmental Effects

- •9.7 General Summary and Conclusions

- •Suggested Reading

- •10 Elimination of Toxicants

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Transport

- •10.3 Renal Elimination

- •10.4 Hepatic Elimination

- •10.4.2 Active Transporters of the Bile Canaliculus

- •10.5 Respiratory Elimination

- •10.6 Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •11 Acute Toxicity

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Acute Exposure and Effect

- •11.3 Dose-response Relationships

- •11.4 Nonconventional Dose-response Relationships

- •11.5 Mechanisms of Acute Toxicity

- •11.5.1 Narcosis

- •11.5.2 Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition

- •11.5.3 Ion Channel Modulators

- •11.5.4 Inhibitors of Cellular Respiration

- •Suggested Reading

- •12 Chemical Carcinogenesis

- •12.1 General Aspects of Cancer

- •12.2 Human Cancer

- •12.2.1 Causes, Incidence, and Mortality Rates of Human Cancer

- •12.2.2 Known Human Carcinogens

- •12.3 Classes of Agents Associated with Carcinogenesis

- •12.3.2 Epigenetic Agents

- •12.4 General Aspects of Chemical Carcinogenesis

- •12.5 Initiation-Promotion Model for Chemical Carcinogenesis

- •12.6 Metabolic Activation of Chemical Carcinogens and DNA Adduct Formation

- •12.7 Oncogenes

- •12.8 Tumor Suppressor Genes

- •12.8.1 Inactivation of Tumor Suppressor Genes

- •12.8.2 p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene

- •12.9 General Aspects of Mutagenicity

- •12.10 Usefulness and Limitations of Mutagenicity Assays for the Identification of Carcinogens

- •Suggested Reading

- •13 Teratogenesis

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.2 Principles of Teratology

- •13.3 Mammalian Embryology Overview

- •13.4 Critical Periods

- •13.5 Historical Teratogens

- •13.5.1 Thalidomide

- •13.5.2 Accutane (Isotetrinoin)

- •13.5.3 Diethylstilbestrol (DES)

- •13.5.4 Alcohol

- •13.6 Testing Protocols

- •13.6.1 FDA Guidelines for Reproduction Studies for Safety Evaluation of Drugs for Human Use

- •13.6.3 Alternative Test Methods

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •Suggested Reading

- •14 Hepatotoxicity

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.1.1 Liver Structure

- •14.1.2 Liver Function

- •14.2 Susceptibility of the Liver

- •14.3 Types of Liver Injury

- •14.3.1 Fatty Liver

- •14.3.2 Necrosis

- •14.3.3 Apoptosis

- •14.3.4 Cholestasis

- •14.3.5 Cirrhosis

- •14.3.6 Hepatitis

- •14.3.7 Oxidative Stress

- •14.3.8 Carcinogenesis

- •14.4 Mechanisms of Hepatotoxicity

- •14.5 Examples of Hepatotoxicants

- •14.5.1 Carbon Tetrachloride

- •14.5.2 Ethanol

- •14.5.3 Bromobenzene

- •14.5.4 Acetaminophen

- •14.6 Metabolic Activation of Hepatotoxicants

- •Suggested Reading

- •15 Nephrotoxicity

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.1.1 Structure of the Renal System

- •15.1.2 Function of the Renal System

- •15.2 Susceptibility of the Renal System

- •15.3 Examples of Nephrotoxicants

- •15.3.1 Metals

- •15.3.2 Aminoglycosides

- •15.3.3 Amphotericin B

- •15.3.4 Chloroform

- •15.3.5 Hexachlorobutadiene

- •Suggested Reading

- •16 Toxicology of the Nervous System

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 The Nervous system

- •16.2.1 The Neuron

- •16.2.2 Neurotransmitters and their Receptors

- •16.2.3 Glial Cells

- •16.3 Toxicant Effects on the Nervous System

- •16.3.1 Structural Effects of Toxicants on Neurons

- •16.3.2 Effects of Toxicants on Other Cells

- •16.4 Neurotoxicity Testing

- •16.4.1 In vivo Tests of Human Exposure

- •16.4.2 In vivo Tests of Animal Exposure

- •16.4.3 In vitro Neurochemical and Histopathological End Points

- •16.5 Summary

- •Suggested Reading

- •17 Endocrine System

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 Endocrine System

- •17.2.1 Nuclear Receptors

- •17.3 Endocrine Disruption

- •17.3.1 Hormone Receptor Agonists

- •17.3.2 Hormone Receptor Antagonists

- •17.3.3 Organizational versus Activational Effects of Endocrine Toxicants

- •17.3.4 Inhibitors of Hormone Synthesis

- •17.3.5 Inducers of Hormone Clearance

- •17.3.6 Hormone Displacement from Binding Proteins

- •17.4 Incidents of Endocrine Toxicity

- •17.4.1 Organizational Toxicity

- •17.4.2 Activational Toxicity

- •17.4.3 Hypothyroidism

- •17.5 Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •18 Respiratory Toxicity

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.1.1 Anatomy

- •18.1.2 Cell Types

- •18.1.3 Function

- •18.2 Susceptibility of the Respiratory System

- •18.2.1 Nasal

- •18.2.2 Lung

- •18.3 Types of Toxic Response

- •18.3.1 Irritation

- •18.3.2 Cell Necrosis

- •18.3.3 Fibrosis

- •18.3.4 Emphysema

- •18.3.5 Allergic Responses

- •18.3.6 Cancer

- •18.3.7 Mediators of Toxic Responses

- •18.4 Examples of Lung Toxicants Requiring Activation

- •18.4.1 Introduction

- •18.4.2 Monocrotaline

- •18.4.3 Ipomeanol

- •18.4.4 Paraquat

- •18.5 Defense Mechanisms

- •Suggested Reading

- •19 Immunotoxicity

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 The Immune System

- •19.3 Immune Suppression

- •19.4 Classification of Immune-Mediated Injury (Hypersensitivity)

- •19.5 Effects of Chemicals on Allergic Disease

- •19.5.1 Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- •19.5.2 Respiratory Allergens

- •19.5.3 Adjuvants

- •19.6 Emerging Issues: Food Allergies, Autoimmunity, and the Developing Immune System

- •Suggested Reading

- •20 Reproductive System

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Male Reproductive Physiology

- •20.3 Mechanisms and Targets of Male Reproductive Toxicants

- •20.3.1 General Mechanisms

- •20.3.2 Effects on Germ Cells

- •20.3.3 Effects on Spermatogenesis and Sperm Quality

- •20.3.4 Effects on Sexual Behavior

- •20.3.5 Effects on Endocrine Function

- •20.4 Female Reproductive Physiology

- •20.5 Mechanisms and Targets of Female Reproductive Toxicants

- •20.5.1 Tranquilizers, Narcotics, and Social Drugs

- •20.5.2 Endocrine Disruptors (EDs)

- •20.5.3 Effects on Germ Cells

- •20.5.4 Effects on the Ovaries and Uterus

- •20.5.5 Effects on Sexual Behavior

- •Suggested Reading

- •21 Toxicity Testing

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Experimental Administration of Toxicants

- •21.2.1 Introduction

- •21.2.2 Routes of Administration

- •21.3 Chemical and Physical Properties

- •21.4 Exposure and Environmental Fate

- •21.5 In vivo Tests

- •21.5.1 Acute and Subchronic Toxicity Tests

- •21.5.2 Chronic Tests

- •21.5.3 Reproductive Toxicity and Teratogenicity

- •21.5.4 Special Tests

- •21.6 In vitro and Other Short-Term Tests

- •21.6.1 Introduction

- •21.6.2 Prokaryote Mutagenicity

- •21.6.3 Eukaryote Mutagenicity

- •21.6.4 DNA Damage and Repair

- •21.6.5 Chromosome Aberrations

- •21.6.6 Mammalian Cell Transformation

- •21.6.7 General Considerations and Testing Sequences

- •21.7 Ecological Effects

- •21.7.1 Laboratory Tests

- •21.7.2 Simulated Field Tests

- •21.7.3 Field Tests

- •21.8 Risk Analysis

- •21.9 The Future of Toxicity Testing

- •Suggested Reading

- •22 Forensic and Clinical Toxicology

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 Foundations of Forensic Toxicology

- •22.3 Courtroom Testimony

- •22.4.1 Documentation Practices

- •22.4.2 Considerations for Forensic Toxicological Analysis

- •22.4.3 Drug Concentrations and Distribution

- •22.5 Laboratory Analyses

- •22.5.1 Colorimetric Screening Tests

- •22.5.2 Thermal Desorption

- •22.5.6 Enzymatic Immunoassay

- •22.6 Analytical Schemes for Toxicant Detection

- •22.7 Clinical Toxicology

- •22.7.1 History Taking

- •22.7.2 Basic Operating Rules in the Treatment of Toxicosis

- •22.7.3 Approaches to Selected Toxicoses

- •Suggested Reading

- •23 Prevention of Toxicity

- •23.1 Introduction

- •23.2 Legislation and Regulation

- •23.2.1 Federal Government

- •23.2.2 State Governments

- •23.2.3 Legislation and Regulation in Other Countries

- •23.3 Prevention in Different Environments

- •23.3.1 Home

- •23.3.2 Workplace

- •23.3.3 Pollution of Air, Water, and Land

- •23.4 Education

- •Suggested Reading

- •24 Human Health Risk Assessment

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Risk Assessment Methods

- •24.2.2 Exposure Assessment

- •24.2.3 Dose Response and Risk Characterization

- •24.3 Noncancer Risk Assessment

- •24.3.1 Default Uncertainty and Modifying Factors

- •24.3.2 Derivation of Developmental Toxicant RfD

- •24.3.3 Determination of RfD and RfC of Naphthalene with the NOAEL Approach

- •24.3.4 Benchmark Dose Approach

- •24.3.5 Determination of BMD and BMDL for ETU

- •24.3.6 Quantifying Risk for Noncarcinogenic Effects: Hazard Quotient

- •24.3.7 Chemical Mixtures

- •24.4 Cancer Risk Assessment

- •24.5 PBPK Modeling

- •Suggested Reading

- •25 Analytical Methods in Toxicology

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Chemical and Physical Methods

- •25.2.1 Sampling

- •25.2.2 Experimental Studies

- •25.2.3 Forensic Studies

- •25.2.4 Sample Preparation

- •25.2.6 Spectroscopy

- •25.2.7 Other Analytical Methods

- •Suggested Reading

- •26 Basics of Environmental Toxicology

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Environmental Persistence

- •26.2.1 Abiotic Degradation

- •26.2.2 Biotic Degradation

- •26.2.3 Nondegradative Elimination Processes

- •26.3 Bioaccumulation

- •26.4 Toxicity

- •26.4.1 Acute Toxicity

- •26.4.2 Mechanisms of Acute Toxicity

- •26.4.3 Chronic Toxicity

- •26.4.5 Abiotic and Biotic Interactions

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •27.1 Introduction

- •27.2 Sources of Toxicants to the Environment

- •27.3 Transport Processes

- •27.3.1 Advection

- •27.3.2 Diffusion

- •27.4 Equilibrium Partitioning

- •27.5 Transformation Processes

- •27.5.1 Reversible Reactions

- •27.5.2 Irreversible Reactions

- •27.6 Environmental Fate Models

- •Suggested Reading

- •28 Environmental Risk Assessment

- •28.1 Introduction

- •28.2 Formulating the Problem

- •28.2.1 Selecting Assessment End Points

- •28.2.2 Developing Conceptual Models

- •28.2.3 Selecting Measures

- •28.3 Analyzing Exposure and Effects Information

- •28.3.1 Characterizing Exposure

- •28.3.2 Characterizing Ecological Effects

- •28.4 Characterizing Risk

- •28.4.1 Estimating Risk

- •28.4.2 Describing Risk

- •28.5 Managing Risk

- •Suggested Reading

- •29 Future Considerations for Environmental and Human Health

- •29.1 Introduction

- •29.2 Risk Management

- •29.3 Risk Assessment

- •29.4 Hazard and Exposure Assessment

- •29.5 In vivo Toxicity

- •29.6 In vitro Toxicity

- •29.7 Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology

- •29.8 Development of Selective Toxicants

- •Glossary

- •Index

58 |

CLASSES OF TOXICANTS: USE CLASSES |

|

|

|

|

|

Cl |

|

Cl |

|

Cl |

Cl |

|

|

|

Cl |

|

|

|

|

|

O |

|

|

|

|

Cl |

|

|

|

|

Cl |

|

|

|

|

Cl |

Cl |

Cl |

|

|

|

|

Cl |

|

|

Dieldrin |

|

DDT |

|

|

|

|

O |

CH3

O NH

S

CH3CH2O P O NO2

O CH2CH3

Parathion |

Carbaryl |

|

Cl |

|

|

N |

NH |

|

N |

||

N |

||

CH3 |

|

|

N |

N |

|

|

||

|

NO2 |

|

Nicotine |

Imidacloprid |

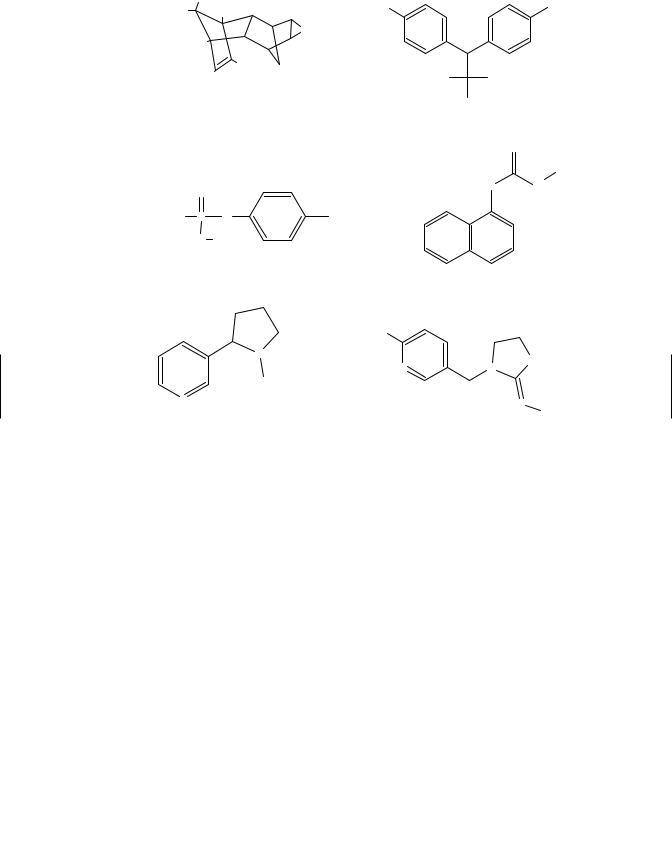

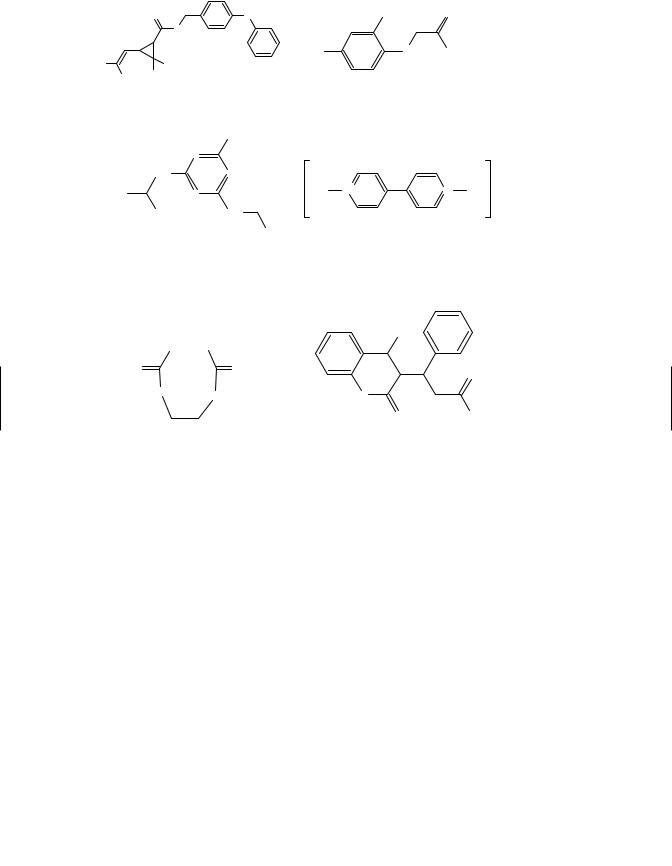

Figure 5.1 Some examples of chemical structures of common pesticides.

DDT, as well as other organochlorines, were used extensively from the 1940s through the 1960s in agriculture and mosquito control, particularly in the World Health Organization (WHO) malaria control programs. The cyclodiene insecticides, such as chlordane were used extensively as termiticides into the 1980s but were removed from the market due to measurable residue levels penetrating into interiors and allegedly causing health problems. Residue levels of chlorinated insecticides continue to be found in the environment and, although the concentrations are now so low as to approach the limit of delectability, there continues to be concern.

5.3.4Organophosphorus Insecticides

Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) are phosphoric acid esters or thiophosphoric acid esters (Figure 5.1) and are among the most widely used pesticides for insect control. During the 1930s and 1940s Gerhard Schrader and coworkers began investigating OP compounds. They realized that the insecticidal properties of these compounds and by the end of the World War II had made many of the insecticidal OPs in use today,

AGRICULTURAL CHEMICALS (PESTICIDES) |

59 |

|

O |

|

O |

Cl |

|

O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cl |

O |

Cl |

CH3 |

|

|

|

Cl |

CH3 |

|

|

|

|

Permethrin |

|

2,4-D |

|

|

|

Cl |

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

NH |

|

N |

|

H3C |

N |

|

H3C N+ |

|

|

CH3 |

|

NH |

|

|

|

|

CH3 |

|

|

Atrazine |

|

|

Paraquat |

|

Mn++ |

|

|

OH |

|

S− −S |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S |

|

S |

|

|

NH |

NH |

|

O |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

O |

|

Maneb |

|

|

Warfarin |

Figure 5.1 (continued )

O

OH

N+ CH3 2Cl−

O

CH3

such as ethyl parathion [O,O-diethyl O-(4-nitrophenyl)phosphorothioate]. The first OP insecticide to find widespread use was tetraethylpyrophosphate (TEPP), approved in Germany in 1944 and marketed as a substitute for nicotine to control aphids. Because of its high mammalian toxicity and rapid hydrolysis in water, TEPP was replaced by other OP insecticides.

Chlorpyrifos [O,O-diethyl O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinyl) phosphorothioate] became one of the largest selling insecticides in the world and had both agricultural and urban uses. The insecticide could be purchased for indoor use by homeowners, but health-related concerns caused USEPA to cancel home indoor and lawn application uses in 2001. The only exception is its continued use as a termiticide.

Parathion was another widely used insecticide due to its stability in aqueous solutions and its broad range of insecticidal activity. However, its high mammalian toxicity through all routes of exposure led to the development of less hazardous compounds. Malathion [diethyl (dimethoxythiophosphorylthio)succinate], in particular, has low mammalian toxicity because mammals possess certain enzymes, the carboxylesterases, that readily hydrolyze the carboxyester link, detoxifying the compound. Insects, by

60 CLASSES OF TOXICANTS: USE CLASSES

contrast, do not readily hydrolyze this ester, and the result is its selective insecticidal action.

OPs are toxic because of their inhibition of the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. This enzyme inhibition results in the accumulation of acetylcholine in nerve tissue and effector organs, with the principal site of action being the peripheral nervous system (PNS) (see Chapter 16). In addition to acute effects, some OP compounds have been associated with delayed neurotoxicity, known as organophosphorus-induced delayed neuropathy (OPIDN). The characteristic clinical sign is bilateral paralysis of the distal muscles, predominantly of the lower extremities, occurring some 7 to 10 days following ingestion (see Chapter 16). Not all OP compounds cause delayed neuropathy. Among the pesticides associated with OPIDN are leptophos, mipafox, EPN, DEF, and trichlorfon. Testing is now required for OP substances prior to their use as insecticides.

The OP and carbamate insecticides are relatively nonpersistent in the environment. They are applied to the crop or directly to the soil as systemic insecticides, and they generally persist from only a few hours to several months. Thus these compounds, in contrast to the organochlorine insecticides, do not represent a serious problem as contaminants of soil and water and rarely enter the human food chain. Being esters, the compounds are susceptible to hydrolysis, and their breakdown products are generally nontoxic. Direct contamination of food by concentrated compounds has been the cause of poisoning episodes in several countries.

5.3.5Carbamate Insecticides

The carbamate insecticides are esters of N -methyl (or occasionally N ,N -dimethyl) carbamic acid (H2NCOOH). The toxicity of the compound varies according to the phenol or alcohol group. One of the most widely used carbamate insecticides is carbaryl (1- napthyl methylcarbamate), a broad spectrum insecticide (Figure 5.1). It is used widely in agriculture, including home gardens where it generally is applied as a dust. Carbaryl is not considered to be a persistent compound, because it is readily hydrolyzed. Based on its formulation, it carries a toxicity classification of II or III with an oral LD50 of 250 mg/kg (rat) and a dermal LC50 of >2000 mg/kg.

An example of an extremely toxic carbamate is aldicarb [2-methyl-2-(methylthio) propionaldehyde]. Both oral and dermal routes are the primary portals of entry, and it has an oral LD50 of 1.0 mg/kg (rat)and a dermal LD50 of 20 mg/kg (rabbit). For this reason it is recommended for application to soils on crops such as cotton, citrus, and sweet potatoes. This compound moves readily through soil profiles and has contaminated groundwater supplies.

Like the OP insecticides, the mode of action of the carbamates is acetylcholinesterase inhibition with the important difference that the inhibition is more rapidly reversed than with OP compounds.

5.3.6Botanical Insecticides

Extracts from plants have been used for centuries to control insects. Nicotine [(S)-3- (1-methyl-2-pyrrolidyl)pyridine] (Figure 5.1) is an alkaloid occurring in a number of plants and was first used as an insecticide in 1763. Nicotine is quite toxic orally as well as dermally. The acute oral LD50 of nicotine sulfate for rats is 83 mg/kg and

AGRICULTURAL CHEMICALS (PESTICIDES) |

61 |

the dermal LD50 is 285 mg/kg. Symptoms of acute nicotine poisoning occur rapidly, and death may occur with a few minutes. In serious poisoning cases death results from respiratory failure due to paralysis of respiratory muscles. In therapy attention is focused primarily on support of respiration.

Pyrethrin is an extract from several types of chrysanthemum, and is one of the oldest insecticides used by humans. There are six esters and acids associated with this botanical insecticide. Pyrethrin is applied at low doses and is considered to be nonpersistent.

Mammalian toxicity to pyrethrins is quite low, apparently due to its rapid breakdown by liver microsomal enzymes and esterases. The acute LD50 to rats is about 1500 mg/kg. The most frequent reaction to pyrethrins is contact dermatitis and allergic respiratory reactions, probably as a result of other constituents in the formulation. Synthetic mimics of pyrethrins, known as the pyrethroids, were developed to overcome the lack of persistence.

5.3.7Pyrethroid Insecticides

As stated, pyrethrins are not persistent, which led pesticide chemists to develop compounds of similar structure having insecticidal activity but being more persistent. This class of insecticides, known as pyrethroids, have greater insecticidal activity and are more photostable than pyrethrins. There are two broad classes of pyrethroids depending on whether the structure contains a cyclopropane ring [e.g., cypermethrin {(±)-α-cyano-3-phenoxybenzyl (±)-cis,trans-3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl 2,2-dimethyl cyclopropanecarboxylate)}] or whether this ring is absent in the molecule [e.g., fenvalerate{(RS )-α-cyano-3-phenoxybenzyl(RS )-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-methylbutyrate}]. They are generally applied at low doses (e.g., 30 g/Ha) and have low mammalian toxicities [e.g., cypermethrin, oral (aqueous suspension) LD50 of 4,123 mg/kg (rat) and dermal LD50 of >2000 mg/kg (rabbit)]. Pyrethroids are used in both agricultural and urban settings (e.g., termiticide; Figure 5.1).

Pyrethrins affect nerve membranes by modifying the sodium and potassium channels, resulting in depolarization of the membranes. Formulations of these insecticides frequently contain the insecticide synergist piperonyl butoxide [5-{2-(2-butoxyethoxy) ethoxymethyl}-6-propyl-1,3-benzodioxole], which acts to increase the efficacy of the insecticide by inhibiting the cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for the breakdown of the insecticide.

5.3.8New Insecticide Classes

There are new classes of insecticides that are applied at low dosages and are extremely effective but are relatively nontoxic to humans. One such class is the fiproles, and one of these receiving major attention is fipronil [(5-amino-1-(2,6-dichloro-4-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl)-4-((1,R,S)-(trifluoromethyl)su-1-H -pyrasole-3-carbonitrile)]. Although it is used on corn, it is becoming a popular termiticide because of its low application rate (ca. 0.01%) and long-term effectiveness. Another class of insecticides, the chloronicotinoids, is represented by imidacloprid [1-(6-chloro-3-pyridin-3-ylmethyl)- N -nitroimidazolidin-2-ylidenamine] (Figure 5.1), which also is applied at low dose rates to soil and effectively controls a number of insect species, including termites.

- #15.08.20134.04 Mб17Hastie T., Tibshirani R., Friedman J. - The Elements of Statistical Learning Data Mining, Inference and Prediction (2002)(en).djvu

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #15.08.201315.44 Mб27Hudlicky M, Pavlath A.E. (eds.) - Chemistry of Organic Fluorine Compounds 2[c] A critical Review (1995)(en).djvu

- #

- #