A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

Contributors

Consultant editors |

|

Richard Hodges |

RH |

Africa – Kevin McDonald |

|

Tom Huffman |

TH |

America – Dean Snow |

|

Ray Inskeep |

RI |

|

|

Robert Jameson |

RJA |

Contributors |

|

Richard Jefferies |

RJE |

Philip Allsworth-Jones |

PA-J |

Simon Kaner |

SK |

Graeme Barker |

GB |

Geoffrey King |

GK |

Noel Barnard |

NB |

Kevin McDonald |

KM |

William Billeck |

WB |

F. Massagrande |

FM |

Sheridan Bowman |

SB |

George Milner |

GM |

Karen Bruhns |

KB |

Peter Mitchell |

PM |

Roy Carlson |

RC |

Steven Mithen |

SM |

Timothy Champion |

TC |

Paul Nicholson |

PTN |

Mike Cowell |

MC |

Clive Orton |

CO |

David Crossley |

DC |

Marilyn Palmer |

MP |

Pavel Dolukhanov |

PD |

Robert W. Park |

RP |

David Gibbins |

DG |

J. Jefferson Reid |

JJR |

Roberta Gilchrist |

RG |

Colin Renfrew |

CR |

Chris Gosden |

CG |

Peter Reynolds |

PRE |

Paul Graves-Brown |

PG-B |

Prudence Rice |

PRI |

Frances Griffith |

FG |

Ian Shaw |

IS |

Charles Higham |

CH |

Carla Sinopoli |

CS |

Ian Hodder |

IH |

John Sutton |

JS |

Preface and

Acknowledgements

The principal aim of this dictionary is to provide readers with a reference tool for the terms, techniques and major sites in archaeology, but it is also intended to reflect the constant state of flux in the discipline. This is a difficult balancing act in a concise volume. Presenting archaeology as a process rather than as a body of knowledge implies that particular sites, cultures, methodologies and conceptual models must also be described in a way that is in some sense ‘provisional’ and open to change. The degree to which the entries succeed in this varies from one subject area to another, but we hope that the book as a whole conveys a sense of the challenges, ambiguities and theoretical context of archaeology as well as the surveyed and excavated data.

We have attempted to make the contents of the dictionary as comprehensive and up-to-date as possible in terms of method and theory. As far as the historical coverage is concerned, the major omission is of classical Greek and Roman history and sites, except where these impinge on other areas (e.g. Roman colonies in North Africa). It is tempting to justify this in terms of the very thorough coverage of the archaeology of the classical world that can be found in recent reference works (e.g. Speake, 1994; Hornblower and Spawforth, 1996). Our real motivation, however, was to make room for a much more comprehensive coverage of previously neglected areas, such as the archaeology of China, Japan and Oceania, as well as longer articles on theory and methodology. To help readers gain an overview of the archaeology of the various geographical regions, many concise essays with regional site maps and cross-references to relevant sites are included in the dictionary (see selective list below).

Otherwise, readers will find little to surprise them in the way the dictionary is structured. It is arranged alphabetically, and adopts the usual conventions for a work of this kind (in the belief that very few readers read ‘How To Use’ pages in dic- tionary-style reference works, or remember them for long if they do). It is common for reference editors to argue that cross-references should only be used where they lead the reader to substantial

further information about the entry that they are reading. This is certainly the most economical approach, but it does make it cumbersome to let readers know that, for example, a comparable site also has an entry in the dictionary, or that a discussion of the archaeology of the region exists (whether or not it greatly adds to the discussion of the individual site). We have therefore adopted a more flexible but inevitably more arbitrary approach, asking ourselves whether the reader might find it useful to be reminded that a related subject possesses its own entry in the dictionary.

As far as the dating of sites and artefacts is concerned, we have tried to ensure that the dates cited as BC or AD by contributors are best-estimates in calendar years. Where radiocarbon dating has been used to date a site, we encouraged authors to supply an educated guess as to the approximate calibrated (i.e. calendar) date, and wherever possible to avoid lengthy discussions of dating. This is clearly not ideal, but we felt that in a brief reference work such as this it was better than asking authors to select out or average radiocarbon dates, or to present these dates without the necessary date ranges and contextual qualifications – this would only have given a falsely ‘scientific’ impression. As some compensation, the site bibliographies can be used to locate more detailed discussions of the dating of sites.

The Wade–Giles method of romanization is used in the articles dealing with the archaeology of China. Despite increasing use, over the last decade, of the mainland Chinese p’in-yin system, the Wade–Giles system remains the standard by sheer weight of accumulated publication over the last century, and by virtue of its continuing use in current and forthcoming publications in English (including Chang Kwang-chi, 1986).

The bibliographies that follow virtually every entry are arranged in chronological order of publication, so that either the primary or the most recent sources can be readily found.

References

G. Speake: A dictionary of ancient history (Oxford, 1994); Chang Kwang-chi: The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven and London, 1986); S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth: The Oxford Classical dictionary, 3rd edn (Oxford, 1996).

Major entries on continents, countries and regions

Africa, America, Arabia (pre-Islamic), Asia, Axum, China, CIS and the Baltic States, Egypt, Europe (medieval and post-medieval), Japan, Lowland Maya, Nubia, Oceania, Persia

Major entries on archaeological theory

Annales, antiquarianism, behavioral archaeology, catastrophe theory, central place theory, chaos theory, cognitive archaeology, contextual archaeology, core– periphery models, covering laws, critical archaeology/ theory, culture history, decision theory, diffusionism, ethnoarchaeology, ethnography, experimental archaeology, falsification, feminist archaeology, foraging theory, forensic archaeology, formal analysis, functionalism, gender archaeology, hydraulic despotism, inductive and deductive explanation, landscape archaeology, logical positivism, logicism, Marxist archaeology, middle-range

PREFACE xiii

theory, neo-evolutionism, nomads, nomothetic (generalizing) approaches, normative explanations, n-transforms, paradigm, phenomenology, post-processual archaeology, post-structuralism, processual archaeology, pulse theory, refuse deposition, secondary products revolution, sign and symbol, site catchment analysis, structuralism, symbolic archaeology, systems theory, theory and theory building, wave of advance, world systems theory.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alyn Shipton, John Davey, Lorna Tunstall and Tessa Harvey for their support (and enormous patience) while waiting for this volume to emerge. We are also grateful to Louise Spencely and Brian Johnson for their hard work on the production and design of the book. The many archaeologists who have contributed to this volume have shown great perseverance during the seemingly everlasting process of commissioning and editing such a lengthy work. Above all we are grateful to Justyna, Ann, Nia and Elin whose lives have been intermittently disrupted by this book.

Ian Shaw

Robert Jameson

Bibliographical

Abbreviations

AA |

American Antiquity |

|

|

|

BSFE |

Bulletin de la Société Française |

||||||

AAR |

African Archaeological Review |

|

|

d’Egyptologie |

|

|

||||||

AE |

Annales d’Ethiopie |

|

|

|

BSGI |

Bulletin de la Service Géologique |

||||||

AI |

Ancient India |

|

|

|

|

|

d’Indochine |

|

|

|

||

AJ |

Antiquaries Journal |

|

|

|

BSPF |

Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique |

||||||

AJA |

American Journal of Archaeology |

|

Française |

|

|

|

|

|||||

AM |

Ancient Mesoamerica |

|

|

|

CA |

Current Anthropology |

|

|||||

AO |

Archiv für Orientforschung |

|

CAJ |

Cambridge Archaeological Journal |

||||||||

AP |

Ancient Pakistan |

|

|

|

CBA |

Council for British Archaeology |

|

|||||

APAMNH |

Anthropological |

Papers |

of |

the |

CdE |

Chronique d’Egypte |

|

|||||

|

American |

Museum |

of |

Natural |

CRASP |

Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des |

||||||

|

History |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sciences, Paris |

|

|

||

ARA |

Annual Review of Anthropology |

CRIPEL |

Cahier de Recherches de l’Institut de |

|||||||||

ARC |

Archaeological |

Review |

from |

|

Papyrologie |

et |

d’Egyptologie |

de |

||||

|

Cambridge |

|

|

|

|

|

Lille |

|

|

|

|

|

AS |

Anatolian Studies |

|

|

|

DA |

Les Dossiers d’Archéologie |

|

|||||

ASAE |

Annales du Service des Antiquités |

EA |

Egyptian |

Archaeology: Bulletin |

of |

|||||||

|

de ‘Egypte |

|

|

|

|

|

the Egypt Exploration Society |

|

||||

Atlal |

The Journal of South Arabian |

EC |

Early China |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

|

EES |

Egypt Exploration Society |

|

||||

AWA |

Advances in World Archaeology |

EFEO |

Ecole Française d’Extrème Orient |

|||||||||

BA |

Biblical Archaeologist |

|

|

|

HA |

Historical Archaeology |

|

|||||

BAR BS/IS |

British |

Archaeological |

Reports |

HJAS |

Harvard Journal of Asian Studies |

|

||||||

|

(British Series/International Series) |

HKJCS |

Hong Kong Journal of Chinese |

|||||||||

BASOR |

Bulletin of the American Schools of |

|

Studies |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Oriental Research |

|

|

|

IA |

Inventaria Archaeologica |

|

|||||

BEFEO |

Bulletin |

de |

l’Ecole |

Française |

IAR |

Industrial Archaeology Review |

|

|||||

|

d’Extrème Orient |

|

|

|

IEJ |

Israel Exploration Journal |

|

|||||

BIE |

Bulletin de l’Institut de l’Egypte |

IJNA |

International |

Journal of Nautical |

||||||||

BIEA |

British Institute in East Africa |

|

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

|||||

BIFAN |

Bulletin |

de l’Institute |

Française |

JA |

Journal Asiatique |

|

|

|||||

|

d’Archéologie Nordafricain |

|

JAA |

Journal |

of |

Anthropological |

||||||

BIFAO |

Bulletin |

de l’Institute |

Française |

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

||||

|

d’Archéologie Oriental |

|

|

JAH |

Journal of African History |

|

||||||

BL |

Boletín de Lima |

|

|

|

|

JAI |

Journal |

of |

the |

Anthropological |

||

BMFA |

Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts |

|

Institute |

|

|

|

|

|||||

BMFEA |

Bulletin of the Museum of Far |

JAOS |

Journal of the American Oriental |

|||||||||

|

Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm |

|

Society |

|

|

|

|

|||||

BMM |

Bulletin of the Metals Museum |

JAR |

Journal of Anthropological Research |

|||||||||

BMMA |

Bulletin |

of |

the |

Metropolitan |

JARCE |

Journal of the American Research |

||||||

|

Museum of Art, New York |

|

|

Center in Egypt |

|

|

||||||

BO |

Bibliotheca Orientalis |

|

|

|

JAS |

Journal of Archaeological Science |

|

|||||

BSEG |

Bulletin de la Société d’Egyptologie |

JASt |

Journal of Asian Studies |

|

||||||||

|

de Genève |

|

|

|

|

JEA |

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ABBREVIATIONS |

xv |

|||||

JESHO |

Journal of the Economic and Social |

|

Research Center in Egypt |

|

|||||||||||

|

History of the Orient |

|

|

|

NGM |

National Geographic Magazine |

|

||||||||

JFA |

Journal of Field Archaeology |

|

NSSEA |

Newsletter of the Society for the |

|||||||||||

JHSN |

Journal of the Historical Society of |

|

Study of Egyptian Antiquities |

|

|||||||||||

|

Nigeria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

OAHSP |

Ohio Archaeological and Historical |

||||||

JICS |

Journal of the Institute of Chinese |

|

Society Publication |

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

OUSPA |

Otago |

University |

Studies |

in |

|||

JJRS |

Japanese |

Journal |

of |

Religious |

|

Prehistoric Anthropology |

|

||||||||

|

Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PA |

Pakistan Archaeology |

|

|

||||

JMA |

Journal |

of |

|

Mediterranean |

PAnth |

Plains Anthropologist |

|

|

|||||||

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

|

|

PEFEO |

Publications |

de |

l’Ecole |

Française |

||||

JNES |

Journal of Near Eastern Studies |

|

|

d’Extrème Orient |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

JOS |

Journal of Oman Studies |

|

|

PEQ |

Palestine Exploration Quarterly |

|

|||||||||

JRAI |

Journal of the Royal Anthropological |

PPS |

Proceedings |

of |

the |

Prehistoric |

|||||||||

|

Institute |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Society |

|

|

|

|

|

|

JRAS |

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |

PSAS |

Proceedings of the Seminar for |

||||||||||||

JSA |

Journal de la Société des |

|

Arabian Studies |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Américanistes |

|

|

|

|

|

PSBA |

Proceedings of the Society of |

|||||||

JSS |

Journal of the Siam Society |

|

|

Biblical Archaeologists |

|

|

|||||||||

JSSEA |

Journal of the Society for the Study |

QAL |

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia |

||||||||||||

|

of Egyptian Antiquities |

|

|

RCHME |

Royal Commission on the Historical |

||||||||||

JWP |

Journal of World Prehistory |

|

|

Monuments of England |

|

|

|||||||||

KCH |

Khao Co Hoc |

|

|

|

|

|

SA |

Scientific American |

|

|

|

||||

KK |

K’ao-ku |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SAAB |

South |

African |

|

Archaeological |

|||

KKHP |

K’ao-ku hsueh-pao |

|

|

|

|

|

Bulletin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

KSIA |

Kratkiye |

soobshcheniya |

Institua |

SAJS |

South African Journal of Science |

|

|||||||||

|

Arkheologii akademiii nauk SSSR |

SCWW |

Ssu-ch’uan wen-wu |

|

|

|

|||||||||

LAA |

Latin American Antiquity |

|

|

SJA |

Southwestern |

|

|

Journal |

of |

||||||

LAAA |

Liverpool |

Annals |

of |

Archaeology |

|

Anthropology |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

and Anthropology |

|

|

|

|

SMA |

Suomen |

muinaismuistoydistyksen |

|||||||

LS |

Libyan Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

aikakauskrija |

|

|

|

|

|

||

MASI |

Memoirs |

of |

the |

Archaeological |

TAPS |

Transactions |

of |

|

the |

American |

|||||

|

Survey of India |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philosophical Society |

|

|

|||||

MDAIK |

Mitteilungen |

des |

Deutschen |

TLAPEPMO Travaux |

|

du |

|

Laboratoire |

|||||||

|

Archäologischen |

|

|

Instituts, |

|

d’Anthropologie, |

de Préhistoire |

et |

|||||||

|

Abteilung Kairo |

|

|

|

|

|

d’Ethnologie des Pays de la |

||||||||

MDOG |

Mitteilungen der Deutsche Orient- |

|

Méditerranée Occidentale |

|

|||||||||||

|

Gesellschaft |

|

|

|

|

|

TP |

T’oung Pao |

|

|

|

|

|

||

MIAS |

Materialy |

i |

issledovanija |

po |

TSCYY |

Ti-ssu-chi yen-chiu |

|

|

|

||||||

|

arheologii SSSR |

|

|

|

|

UJ |

Uganda Journal |

|

|

|

|

||||

MJA |

Midcontinental |

|

Journal |

of |

WA |

World Archaeology |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Archaeology |

|

|

|

|

|

WAJA |

West African Journal of Archaeology |

|||||||

MQRISA |

Modern Quaternary |

Research |

in |

WW |

Wen-wu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Southeast Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

YCHP |

Yen-ching hsüeh pao |

|

|

|||||

MS |

Monumenta Serica |

|

|

|

|

YJSS |

Yenching Journal |

of |

Sinological |

||||||

MSGI |

Mémoires du Service Géologique de |

|

Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

l’Indochine |

|

|

|

|

|

ZÄS |

Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache |

|||||||

NA |

Nyame Akuma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

und Altertumskunde |

|

|

|||||

NAR |

Norwegian Archaeological Review |

ZDMG |

Zeitschrift |

der |

|

Deutschen |

|||||||||

NARCE |

Newsletter |

of |

the |

|

American |

|

Morganländischen Gesellschaft |

|

|||||||

To

Justyna, Ann, Nia and Elin

A Dictionary of Archaeology

Edited by Ian Shaw, Robert Jameson Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1999

A

AAS see ATOMIC ABSORPTION

SPECTROPHOTOMETRY

Abadiya see HIW-SEMAINA REGION

Abkan see CATARACT TRADITION

Abri Pataud Large collapsed rock-shelter of the Upper Palaeolithic in the village of Les Eyzies, southwest France. From around 35,000 BC, the site was intermittently occupied over many thousands of years, providing evidence of tools, hearths and living areas from the early AURIGNACIAN through to the Proto-Magdelanian or later. Excavated in the 1950s and 1960s, the radiocarbon dating of the cultural sequence at Abri Pataud has greatly clarified the absolute chronology of the early Upper Palaeolithic. Various engraved and painted limestone plaques and a female figure in bas-relief were recovered from the Périgordian VI level.

Palaeolithic excavation techniques were significantly refined at Abri Pataud. First the excavator, Movius, developed a rigid suspended grid system to help control the excavation area. Second, the stratigraphy was determined by test trenches dug on either side of the edges of the main excavation. This allowed Movius to expose extensively and examine in situ the occupation layers in between the trenches. The analysis of the finds from Abri Pataud has been marked by an innovative and extensive use of attribute analysis (e.g. Bricker and David).

H.L. Movius Jr., ed.: ‘Excavation of the Abri Pataud, Les Eyzies (Dordogne)’, American School of Prehistoric Research 30/31 (1977); H. Bricker and N. David: ‘Excavation of the Abri Pataud, Les Eyzies (Dordogne): the Périgordian VI (Level 3) assemblage’, American School of Prehistoric Research 34 (1984).

RJA

Its plan must therefore have been similar to Old Kingdom pyramid complexes such as those at SAQQARA and ABUSIR. The excavation of Abu Ghurob, by the German archaeologists Ludwig Borchardt, Heinrich Schäfer and F.W. von Bissing (1898–1901), was a typical example of late 19th century ‘clearance’, designed primarily to recover choice relief blocks for European collections.

F.W. von Bissing et al.: Das Re-Heiligtum des Königs Ne- Woser-Re, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1905–28); D. Wildung:

Ni-User-Re: Sonnenkönig-Sonnengott (Munich, 1985).

IS

Abu Habba see SIPPAR

Abu Hureyra, Tell Settlement site dating to the

EPIPALAEOLITHIC, the ACERAMIC NEOLITHIC and

the ceramic Neolithic (c.8000–5000 BC), which covers an area of 11.5 ha on the southern bank of the Euphrates in northern Syria. It was excavated in 1972–3 by Andrew Moore as part of the rescue work in advance of the construction of a new Euphrates dam (Moore 1975; Moore et al, forthcoming). The archaeological remains of Neolithic mud-brick houses at Abu Hureyra – like those at the roughly contemporaneous sites of Bouqras (in Syria) and AIN GHAZAL (in Jordan) – provide a foretaste of the more urbanized culture which was to emerge most strikingly at in Anatolia.

A.M.T. Moore: ‘The excavation of Tell Abu Hureyra in Syria: a preliminary report’, PPS 41 (1975), 50–77; T. Molleson, G. Comerford and A.M.T. Moore: ‘A Neolithic painted skull from Tell Abu Hureyra, northern Syria’, CAJ 2/2 (1992), 230–33; A.M.T. Moore, G. Hillman and A. Legge: Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates

(forthcoming).

IS

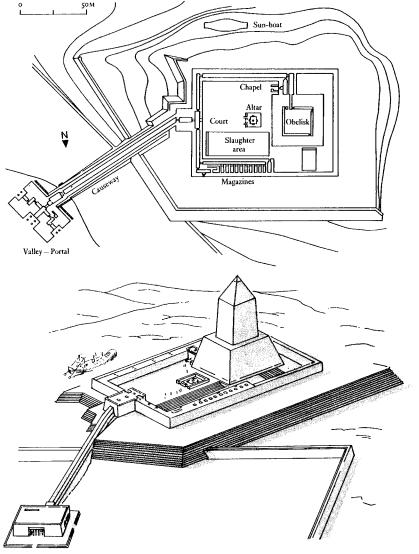

Abu Ghurob Egyptian sun temple, 10 km southwest of Cairo, built by the 5th dynasty ruler Neuserra (c.2400 BC) and dedicated to the sun-god Ra. It consisted of an upper temple, including a stone-built obelisk and open courtyard with travertine altar, as well as a causeway and valley temple.

Abu Roash (Abu Rawash) Egyptian cemetery at the northern end of the Memphite necropolis, 10 km west of Cairo, which was excavated by Emile Chassinat in 1901. The earliest remains at the site are mud-brick mastaba-tombs, which contain artefacts bearing the names of the 1st-dynasty kings

2ABU ROASH

Figure 1 Abu Ghurob Plan and reconstruction drawing of the sun temple of Nyuserra at Abu Ghurob, Egypt. Source: W. Stevenson Smith: The art and architecture of ancient Egypt, 2nd edn (Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1981), figs 124, 125.

Aha and Den (c.3000–2900 BC). The main surviving structure at the site is the 4th-dynasty unfinished pyramid of King Djedefra (c.2528–2520 BC), which was evidently originally intended to be cased in red granite. To the east of the pyramid Chassinat uncovered the remains of a mortuary temple, a trench intended to hold a solar boat (like those at GIZA), and a cemetery of Old Kingdom private tombs. In the mid-19th century, the German Egyptologist Lepsius noted the presence of a ruined mud-brick pyramid about 2 km to the south of the

complex of Djedefra, but only its burial chamber has survived into modern times.

F. Bisson de la Roque: Rapport sur les fouilles d’AbuRoasch, 3 vols (Cairo, 1924–5); V. Maragioglio and C. Rinaldi: L’architettura della piramidi Menfite V (Rapallo, 1966); C. Desroches Noblecourt, ed.: Un siècle de fouilles françaises en Egypte, 1880–1980 (Paris, 1981), 44–53; M. Vallogia: Le complex funraire de Radjedef Abu Roash: tat de la question et perspectives de recherches, BDFE 130 (1994), 5–17.

IS

Abu Salabikh Cluster of mounds comprising the site of a 4th–3rd millennium Sumerian town (the ancient name of which is uncertain) near the site of NIPPUR. The site was excavated by Nicholas Postgate mainly during the 1980s. One of the mounds consists of deposits dating to the Uruk period (c.4300–3100 BC) but the others date principally to the Early Dynastic phase (c.2900–2350 BC); the site was evidently occupied in the later periods, but the Sumerian remains are close to the modern ground-level. The survey and excavation at Abu Salabikh from the 1970s onwards has included a number of innovative techniques; on the West Mound, for instance, the whole Early Dynastic surface was investigated by scraping off the uppermost deposits, thus enabling the walls and features to be accurately planned over a wide area of the town (Postgate 1983). The exposure of large areas of mud-brick walling across the site has provided the excavators with an unusual opportunity to analyse large-scale settlement patterns within a Sumerian city (Matthews et al. 1994).

J.N. Postgate: ‘Abu Salabikh’, Fifty years of Mesopotamian discovery, ed. J. Curtis (London, 1982), 48–61; ––––: Abu Salabikh excavations I: The West Mound surface clearance

(London, 1983); ––––: ‘How many Sumerians per hectare? – probing the anatomy of an early city’, CAJ 4/1 (1994), 47–65; W. Matthews et al.: ‘The imprint of living in an early Mesopotamian city: questions and answers’,

Whither environmental archaeology?, ed. R. Luff and P. Rowley-Conwy (Oxford, 1994).

IS

Abu Shahrein see ERIDU

Abu Simbel Pair of Egyptian rock-temples, 280 km south of Aswan, built by Ramesses II (c.1290–1224 BC). The ‘Great Temple’ is dedicated to the king and the principal Egyptian deities, Amon-Ra, Ra-Horakhty and Ptah. Its sanctuary is precisely located so that the rays of the rising sun penetrate to the inner sanctum on two days of the year (22 February and 22 October), thus illuminating four statues in the inner sanctum. The ‘Small Temple’ is dedicated to the king’s wife, Nefertari. Both temples were carved into the cliffs to the west of the Nile, with colossal statues of the king and queen sculpted along the outer façades. Abu Simbel was among the Nubian monuments saved from LAKE NASSER (the reservoir created by the construction of the Aswan High Dam). In the late 1960s, in an operation costing some $40 million, the temples were dismantled into separate blocks and then reassembled at a location 64 m higher and 200 m to the west of the original site. The alignment

ABYDOS 3

of the relocated Great Temple has been maintained so that the sanctuary is still illuminated twice a year.

W. MacQuitty: Abu Simbel (London, 1965); C. Desroches-Noblecourt and C. Kuentz: Le petit temple d’Abou Simbel, 2 vols (Cairo, 1968); T. Säve-Söderbergh, ed.: Temples and tombs of ancient Nubia (London, 1987).

IS

Abusir Egyptian royal necropolis and temple site, located 25 km west of Cairo. The major archaeological remains at Abusir are the pyramids of four of the 5th-dynasty kings (Sahura, Neferirkara, Neuserra and Neferefra (c.2458–2392 BC) and the sun temple of Userkaf (c. 2465–2458 BC), which were first scientifically excavated by Ludwig Borchardt. During the 1980s and 1990s other parts of the site, including the mastaba of Ptahshepses, the mortuary temple of Neferefra, the pyramid complex of Queen Khentkawes (mother of Sahura and Neferirkara) and several Late Period shaft tombs (including that of the chief physician Udjahorresnet), have been excavated by a Czechoslovakian team. The contents of papyrus archives discovered in the mortuary temple of Neferirkara have shed useful light on the structure and mechanisms of Egyptian Old Kingdom temple administration, especially when combined with archaeological evidence from sites such as

DAHSHUR, GIZA and SAQQARA.

L. Borchardt: Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Ne-user-Re (Leipzig, 1907); ––––: Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Nefer- ir-ka-Re (Leipzig, 1909); ––––: Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahu-Re (Leipzig, 1910–13); H. Ricke: Das Sonnenheiligtum des Königs Userkaf (Cairo, 1965; Wiesbaden, 1969); P. Kaplony: ‘Das Papyrus Archiv von Abusir’, Orientalia 41 (1972), 180–244; P. PosenerKriéger: Les archives du temple funéraire de Neferirkare (Les papyrus d’Abousir), 2 vols (Cairo, 1976); M. Verner: Preliminary excavation reports in ZÄS (1982–).

IS

Abydos (anc. Abdjw) Pharaonic site on the west bank of the Nile, 50 km south of Sohag. Abydos was inhabited from the late predynastic to the Christian period (c.4000 BC–AD 641). As well as the Early Dynastic royal necropolis of Umm el-Qaðab (dating to c.3000–2649 BC), the site includes the temple of the canine god Osiris-Khentimentiu (Kom elSultan), the temples of Seti I and Ramesses II, the Osireion (an archaizing ‘dummy tomb’ of Osiris), an extensive settlement and numerous graves and cenotaphs of humans and animals. During the second half of the 19th century the site was excavated by Auguste Mariette and Emile Amélineau, whose techniques amounted to little more than treasure hunting.

4ABYDOS

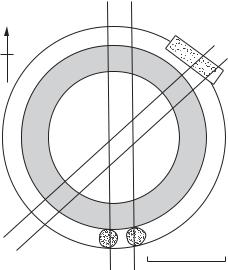

The scientific analysis of the site began with Flinders Petrie, who re-excavated the Early Dynastic royal tombs between 1899 and 1901. Peet’s 1913 season included the excavation of a small circular area of settlement dating to the late predynastic period (Gerzean: c.3500–3000 BC), including an assemblage of over 300 stone tools, a midden and several hearths (discussed in Hoffman 1979). Although Peet simply dug two trenches through an area with a diameter of about 30 m, this was nevertheless the first scientific examination of an Egyptian settlement of the predynastic period, predating even Gertrude Caton-Thompson’s pioneering work at the stratified settlement of Hammamia (see el-BADARI).

By re-analysing the results of the excavations of Petrie and Eric Peet, Barry Kemp (1967) has deduced that the Early Dynastic royal tombs were complemented by a row of ‘funerary palaces’ to the east, which may well have been the prototype of the mortuary temples in Old Kingdom pyramid complexes. In 1991 the excavations of David O’Connor revealed further support for this theory in the form of a number of Early Dynastic wooden boat graves near the Shunet el-Zebib, best surviving of the ‘funerary palaces’ (O’Connor 1991). Since 1973 German excavators have reexamined the Early Dynastic royal cemetery and its vicinity; their findings include conclusive proof of

N

Culinary zone |

Osireion Kiln |

|

Habitation zone (charcoal stained soil)

“Borer” zone

“B” Trench

“A”Trench

Hearths 0 |

10 m |

Figure 2 Abydos Schematic plan of the area of the late Gerzean settlement excavated by Eric Peet at Abydos, Egypt. Source: M.A. Hoffman: Egypt before the pharaohs (London: Ark, 1980), fig. 44.

cultural continuity between the adjacent late pre-dynastic Cemetery U and the royal graves dated to ‘Dynasty 0’, the beginning of the Early Dynastic period (Dreyer 1992).

A Mariette: Abydos: description des fouilles exécutées sur l’emplacement de cette ville, 2 vols (Paris, 1869–80); W.M.F. Petrie: The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties, 2 vols (London, 1900–1); B.J. Kemp: ‘The Egyptian 1st dynasty royal cemetery’, Antiquity 41 (1967), 22–32; M.A. Hoffman: Egypt before the pharaohs (New York, 1979), 150–4; D. O’Connor: ‘Boat graves and pyramid origins: new discoveries at Abydos, Egypt’, Expedition 33/3 (1991), 5–17; G. Dreyer: ‘Recent discoveries at Abydos Cemetery U’, The Nile Delta in transition: 4th–3rd millennium BC, ed. E.C.M. van den Brink (Tel Aviv, 1992), 293–9.

IS

accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) As used in RADIOCARBON DATING, AMS selects and counts the 14C atoms in the sample relative to the many orders of magnitude higher number of 13C or

12C atoms (see CONVENTIONAL RADIOCARBON

DATING). Mass spectrometry differentiates between charged particles of very nearly the same mass, travelling at the same velocity, by subjecting them to a magnetic field. The heavier particles are deflected least. An accelerator, used in conjunction with mass spectrometry, increases the velocity of the particles which enhances differentiation. AMS needs only of the order of 1 mg of carbon (e.g. the amount that could be derived from about 0.5 g of bone) but precision is limited, typically ± 60 years at best.

J.A.J. Gowlett and R.E.M. Hedges, eds Archaeological results from accelerator dating (Oxford, 1986); H.E. Gove: ‘The history of AMS, its advantages over decay counting: applications and prospects’, Radiocarbon after four decades: an interdisciplinary perspective, ed. R.E. Taylor, A. Long and R.S. Kra (Berlin and New York, 1992).

SB

accllahuasi Houses in which INCA ‘chosen women’ (i.e. women removed from child-bearing to prepare beer and to weave for the state) lived and worked.

G. Gasparini and L. Margolis: Inca architecture (Indiana, 1980), 56, 67, 192, 264; B. Cobo: Inca religion and customs, trans. R. Hamilton (Texas, 1990), ch. 37.

KB

Açemhöyük (anc. Burushkhattum) Settlement mound in the central plain of Anatolia, which has been identified with the city of Burushkhattum (the HITTITE Purushkhanda). The site has been excavated since 1963 by Nimet Özgüç, revealing occupation levels stretching back to the 5th