A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfrecord numerous military and punitive expeditions, while the role of the hunt (which is one of the most frequently mentioned royal activities) may well be significant. The numerous place-names recorded in connection with both military and hunting expeditions offer plenty of opportunity for academic argument among those who attempt to identify the archaic names with present-day geographical features and similarly named localities.

Such documents as the records of expeditions to Ch’iang-fang (‘the Ch’iang regions’) for the capture of Ch’iang peoples as well as for sacrificial and menial purposes, have been eagerly cited by Marxist-inspired writers in an effort to follow the Marxist model of history. (The nature of the chung (‘the multitudes’) would need to be defined without bias, as a step towards clarification of the status and role of peasants, craftsmen, and soldiers in Shang society.) Thus the ‘approved’ periodization of Chinese history since 1949 follows the evolutionary stages of human society according to Marx and Engels (and Kuo Mo-jo’s interpretations thereof): primitive society, slave society, feudal society, and capitalistic society (see Kuo Mo-jo 1954). Much has been written on the problems of ‘periodization’ since 1945 (when Kuo changed his earlier interpretation of Shang as a ‘primitive society’ to that of a ‘slave society’). There are more than a score of ‘systems’ which attempt to establish the date of the Chou conquest of Shang which, in both the archaeological literature (inscribed bronze ritual vessels) and the traditional literary sources, is ascribed to Wu Wang, the first king of the newly established dynasty. These systems disagree on the date of the conquest (which ranges from 1122 BC – the orthodox date used here – to 1111, 1110, 1088, 1078, 1075, 1066, 1063, 1050, 1045, 1027 and 1018 BC), and there is also conflict among the historicoliterary sources with regard to the reign-lengths of individual kings.

The Bamboo Annals have exerted a considerable influence on the chronological problem but the value of this semi-archaeological document as an historical source is very much open to question. Attempts to establish the chronology have further sought to employ astronomical data as recorded in the traditional literature along with reign-years and event-dates recorded in the bronze inscriptions, but these generally lack the names of the kings in question, and only occasionally record the year of reign, while there are numerous problems attending the interpretation of the events recorded. Arthistorical assessments of vessel typology and decoration are often cited in support of one favoured chronology or another. To sum up, how-

CHINA 155

ever, unless some major find of unambiguous purport turns up, the problem of Shang and Chou chronology will remain unsolved and continue to fuel academic exercises of debatable value.

The Chou dynasty, comprising 35 rulers, was originally located in the area of present-day Chouyuan. It established its hegemony over Shang and most of the then ‘civilized’ (as opposed to ‘barbarian’) areas of China, instituting an administrative system similar to Western-style feudalism. The first half of the period is termed WESTERN CHOU (1122–771 BC), which ends with the transfer of the ROYAL DOMAIN eastwards from Hao and Feng (near present-day Hsi-an) to Lo-yi (near Lo-yang). This is followed by the EASTERN CHOU period (770–255 BC), which in turn is divided into the Ch’un-ch’iu and Chan-kuo phases (770–482 BC and 481–221 BC respectively). With the ascendancy of CH’IN towards the close of the Chan-kuo period, the last decades of this phase are sometimes classed as falling within the Ch’in period.

Since the establishment of the modern political regime in China, the Chinese use of the term ‘feudalism’ (rendered as feng-chien) has been influenced by ideology. The so-called feudal institutions in China are actually quite different to those of the late 9th to early 13th centuries AD in western and central Europe, from which the term feudalism (feodalus, feodalité) derives. However, because of the preoccupation of Chinese writers with the existence of a ‘slave society’ during Shang, the concept of a ‘feudal society’ has been extended from Chou to Ch’ing.

The Western Chou period, at its inception and for several centuries thereafter, manifests many of the characteristics of feudalism as detailed by Ch’i Ssu-ho (1948) and further elaborated by Creel (1970). However, the latter’s working definition of feudalism, as ‘a system of government in which the ruler personally delegates limited sovereignty over portions of his territory to vassals’ (Creel 1970: 320), is, like most others, open to debate. Nevertheless, there exist a remarkable number of similar features, so much so that it is as well to recollect Marc Bloch’s observation: ‘it is by no means impossible that societies different from our own should have passed through a phase closely resembling that which has just been defined. If so, it is legitimate to call them feudal during that phase’ (Bloch 1961: 446).

During Eastern Chou (771–255 BC) the power of the Chou kings reached a low ebb and with the rise of the ‘Five Hegemons’ (wu-pa), powerful rulers of states who, one after the other, practically usurped

156 CHINA

the royal functions and authority, the Chou kings became little more than figureheads. In the Chankuo period a picture of internecine warfare emerged. It was during this phase that the rulers of such states as WU, YÜEH, LU and CH’U, which came into prominence early in Eastern Chou times, generally adopted feudal titles and even the title of ‘king’. They also claimed lineage, or intermarriages, with the Chi-surnamed royal family of the Chou dynasty, and records of their forebears having assisted the founder kings Wen and Wu in the conquest of Shang abound in the traditional literature.

From the close of the Ch’un-ch’iu period, the traditional texts which are considered to have been compiled during this period, present a wealth of information on many aspects of contemporary Chinese administration, society, thought, warfare and history in general. The form in which we now know them, however, is mainly the result of Han period recensions: contemporary archaeological versions are limited, since recent finds mainly derive from Han-period burials.

There is a vast literature in Chinese emanating from such scholars as Tung Tso-pin, Ch’en Mengchia, Hu Hou-hsuan and Chang Cheng-lan. These works are based on the oracle bones and cover many aspects of the Shang period (see Keightley 1978).

Ch’i Ssu-ho: ‘Chou-tai hsi-ming-li k’ao’ [An investigation into the investiture ceremony of the Chou Period], YCHP 23 (1947), 197–226; ––––: ‘A comparison between Chinese and European feudal institutions’, YJSS 4 (1948): 1–13; Kuo Mo-jo: Chung-kuo ku-tai she-hiu yenchiu (Peking, 1954); N. Barnard: ‘A recently excavated bronze of Western Chou date’ MS 17 (1958), 12–46; M. Bloch: Feudal society (London, 1961); H.G. Creel: The origins of statecraft in China (Chicago, 1970); N. Barnard: ‘The Nieh Ling Yi’, JICS 9 (1978), 585–628; D.N. Keightley: Sources of Shang history: the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley, 1978); ––––: ‘The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou chronology’, HJAS 38/2 (1978), 423–38; Chang Kwang-chih: Shang civilization (New Haven, 1980); D.W. Pankenier: ‘Astronomical dates in Shang and Western Chou’ EC 7 (1981/2), 2–37; D.N. Keightley, ed.: The origins of Chinese civilization

(Berkeley, 1983); Chang Kwang-chih, ed.: Studies of Shang archaeology (New Haven, 1986); D.N. Keightley:

The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven, 1986); E.L. Shaughnessy: ‘The “Current” Bamboo Annals and the date of the Zhou conquest of Shang’, HJAS 46/1 (1986), 149–80; N. Barnard: ‘Astronomical data from ancient Chinese records and the requirements of historical research methodology’, East Asian History 6 (1993), 47–74.

3 Writing and texts. The Chinese script employed throughout the vast literary heritage of China, from Han times up to the latest issue of such archaeologi-

cal journals as Wen-wu (‘cultural relics’) and K’aoku (‘archaeology’), is very close in principle to that preserved in the oracle bones, inscriptions on bronze and other artefacts. Many extant characters in common use today are directly descended from those used in pre-Han times. There are, of course, numerous obsolete characters to be noted throughout the archaeological documents; these create some difficulties in interpretation. Nevertheless, the links between the culture of ‘modern China’ and that of the past two millennia (‘imperial China’, from Han to Ch’ing i.e. 220 BC–AD 1911), and the preceding two millennia (the ‘era of cultural foundations’, from early Shang to Ch’in: c.2000–221 BC) constitute a unique cultural continuum spanning four millennia.

Incised graphs on ceramics of pre-Shang date comprise some of the earliest examples of Chinese ‘characters’. Although many are of uncertain significance, many recent studies are devoted to the important role that these ceramic markings appear to have played in the development towards true characters. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that the markings were combined to form sentences. It was not until Middle to Late Shang times that a written language developed. Systematic study of the ceramic symbols has resulted in the interesting discovery, however, that quite a few signs are repeated over a wide geographical range of sites – a situation that may well be relevant to the development of the Chinese character (Cheung 1983: 323–91); not unexpectedly, too, those markings which appear fairly certainly to be numerals have the greater incidence. Strings of ‘characters’ such as those incised on pottery in the Wu-ch’eng- ts’un find are – like the bronze artefacts found there

– probably local emulations of the contemporary Shang script, made without an actual understanding of ‘writing’.

The practice from Late Shang to Chou times of incorporating records of contemporary significance cast in bronze (as opposed to being incised into the metal, which does not occur until the late Ch’unch’iu period) has resulted in the gradual recovery of a large corpus of bronze ‘documents’. Publications of numerous repositories of bronze inscriptions have appeared over the last 900 years; these texts (excluding repeated inscriptions) amount to almost 10,000 items. Most are unprovenanced, and a large number of doubtful materials are present. However, the gradual increase in archaeological exploration in China from the 1920s, and especially the tremendous momentum since the 1950s, has resulted in the controlled excavation of some 3300 new bronze inscriptions. This corpus of well-

provenanced historical documents is now available as a means of control. Inscriptions range from large documents of 500 or so characters to groups of as few as five or six characters. Inscriptions of less than five characters are generally of the ‘clan-sign’ type (i.e. the phrase ‘X has cast this vessel’ followed by a clan-sign). Interpretations of the archaeological documents still tend to be influenced too strongly by long-established concepts engendered by the traditional literature. Nevertheless, studies over the last century, and particularly over the last few decades, have succeeded in clarifying the nature of the culture and civilization of Shang and Chou (see CHINA 2 above). The bronze documents, however, being the products of the ruling classes, naturally require supplementary evidence from the widest possible range of archaeological data to obtain a reasonably reliable and more general view of the society of the time.

The earliest examples of brush-written characters are on Shang oracle bones and ceramics. Presumably, during Late Shang and Western Chou bamboo, wood, and perhaps even silk, provided the ground for the writing of substantial amounts of text. It was not until Late Ch’un-ch’iu (c.600 BC), however, that writings on these materials entered the archaeological context. The most common surviving brush-written texts are INVENTORIES OF TOMB FURNISHINGS, usually recorded on wooden or bamboo strips. Other subjects include writings on fortune-telling, laws and ordinances, lists of punishments and state annals.

As far as writings on silk are concerned, the longest surviving single text is the Ch’u silk manuscript, which was the product of tomb robbery in Ch’ang-sha in the 1930s and is about 950 characters in length. From Han tombs, however, there are particularly impressive finds of archaeological documents such as those from WU-WEI (Mo-chui- tzu), Kan-su; Yün-meng (Shui-hu-ti), Hu-pei; Lin-yi-hsien (Yin-chüeh-shan), Shan-tung; HSINYANG, Ho-nan; Ch’ang-sha, and Pao-shan, Hu-pei. The subject-matter comprises tomb inventories, astrological works, maps, medical works, contemporary versions of the transmitted traditional literature, and lost texts of various kinds. The documents are often of substantial size; many are written on strips of bamboo or wood and bound together with cord, while others are written on scrolls of silk.

Recovery of textual data from ancient burials has invariably been heralded in China as an event of special importance. There has been a tradition of palaeographic studies, literary, philosophical, and historical writing, and textual criticism for 2000 years. Since Han times, these efforts have been

CHINA 157

directed towards (and in turn strongly tempered by) the traditional literature. The accumulated background of archival and intellectual activity, which is embodied in a vast volume of publications, many of the extant original printings of which date back to Sung times (c.AD 1100), is now receiving renewed attention from a variety of directions.

Research devoted to the newly discovered archaeological documents is gradually being published. Studies of the new materials have led to intensive researches into the traditional literature and have already resulted in revisions, modifications, and confirmations of age-old concepts. There is a constant process of review concerning the interpretations of individual characters, phrases, and even whole passages of text, as preserved throughout numerous commentaries from Han times. A renaissance in the age-old study of the traditional literature has thus been in progress over the last few decades, and has exerted a considerable influence over interpretations of archaeological data.

Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin: Written on bamboo and silk: the beginnings of Chinese books and inscriptions (Chicago and London, 1963); M. Loewe: Records of Han administration, 2 vols (Cambridge, 1967); N. Barnard: The Ch’u silk manuscript: translation and commentary (Canberra, 1973); Cheung Kwong-yue: ‘Recent archaeological evidence relating to the origin of Chinese characters’, Origins of Chinese civilization, ed. D.N. Keightley (Berkeley, 1983), 323–91.

4. The history of the archaeology of China. Two major features have characterized research and writing since the beginnings of modern archaeology in China over 60 years ago. First, there has been widespread use of western-style approaches in fieldwork, as well as the adoption (and adaptions) of western-style interpretational assessments of the data unearthed. Where these activities are directed to pre-Shang Neolithic contexts, the approach differs little from that of archaeology in other prehistoric cultural spheres. There are, however, fewer applications of the mathematical and statistical approaches of ‘NEW ARCHAEOLOGY’, the nature of which has only recently begun to be discussed in China (e.g. Huo Wei 1992).

Not unexpectedly, the more impressive excavations which relate so closely to the formative eras of Chinese culture, from Early Shang to Ch’in (c.2000–221 BC) occupy much the larger proportion of the published reports and associated studies. This is largely because of the vast quantity of textual documentation unearthed: oracle bone texts, inscribed bronzes, bamboo tablets, and silk manuscripts. We have already noted the marked effect of

158 CHINA

the traditional literature (and also, since 1949, that of 19thand 20th-century ideological influences) upon the manner in which the overall archaeological context is assessed.

The influx of western influences is to be noted mainly in the conduct of fieldwork (since the late 1920s), museum conservation (from the 1950s), applications of science (from the 1970s), systematic methods in the study of archaeological data (gradually, but with increasing acumen, over the whole period), and, over the last decade a welcome tendency among some writers to break away from the ideological restraints imposed since 1949. The importance of archaeological data to the historian has, of course, long been realized. Indeed, we should recall that before the modern era China had already developed critical approaches to history, notably in the 17th and 18th centuries, although these unfortunately languished until the late 19th century. Revivals of historical criticism thence stemmed from the works of K’ang Yu-wei, Hu Shih, Ku Chieh-kang, Liang Chi-ch’ao, and others who were strongly influenced by (or had studied in) the West. In the realm of archaeology, however, it was mainly through the persuasive expositions of the theoretical evolutionary models of Marx and Engels by Kuo Mo-jo in the 1930s, that these politically acceptable (albeit somewhat antiquated and materialistic) approaches were to come into their own after the events of 1949. They still remain an issue to be weighed carefully by users of Chinese archaeological reports and secondary writings.

Considerable time and effort is spent on the reconstruction and repair of archaeological artefacts but, unfortunately, often without subjecting the materials to thorough scientific scrutiny beforehand so as to elicit all data of possible significance. Much of the reconstruction work, however, is of a high standard – especially where materials of exceptional significance are concerned, e.g. the bronze chariot and horses (No. 2) found in a pit burial to the west of the tomb mound of Shih-huang-ti, the ‘terracotta army’ to the east of the mound, numerous individual items ranging from Neolithic pottery through textiles, brush-written bamboo tablets, lacquer-ware, to gold, silver, bronze and iron artefacts. Owing to the ravages of time and burial conditions, restoration work is also occupied with the production of facsimile representations of the original artefacts; the results are usually excellent. Possibly, these activities might seem to savour of the financial aspects of ‘making the past work for the present’. The preparation of major archaeological sites as tourist attractions, some with especially con-

structed buildings to house them (and museums to display the treasures unearthed), and, of course, the organization of overseas exhibitions, are all excellent money-making investments.

This contrasts with the rudimentary level of preservation of archaeological artefacts characteristic of numerous provincial and lesser museums, despite the continual appearance of articles relating to conservation techniques in the archaeological journals. The frequent instances of untreated ‘bronze disease’ among items on display is but one indication of this. Few such museums have proper conservation facilities let alone staff with adequate expertise to engage even in stop-gap measures. There are, of course, exceptions to be observed among the comparatively few better-endowed museums where conservation activities and laboratory research have progressed appreciably – often the latter is conducted in co-operation with outside research laboratories.

Scientific examination of the materials unearthed has progressed well in several archaeological institutes and museums, but there is an appreciable lack of equipment and qualified staff, while a considerable quantity of potentially valuable data remains unexamined, or incompletely examined, in many institutes and museums throughout the country – much of it lying dormant in store-rooms where access is limited. Generally, however, this situation has been balanced by the extensive publication of detailed and exact measurements of site areas, building foundations, kilns, skeletal remains, and of the vast quantities of artefacts unearthed; as well as the considerable proportion of fine quality drawings, décor rubbings, adequate and gradually improving photographic coverage, and quite detailed descriptive notes on individual artefacts. Along with these data, radiocarbon assessments, elemental analyses, microscopic examinations, and other such laboratory-derived information are occasionally incorporated where the institutes concerned have been fortunate enough to obtain the interest of outside laboratories to undertake such work.

Because of the comparative paucity of scientifically derived information, and the lack of experience of many of the report compilers in the use of such data (when it does become available), misleading interpretations occur at times. One has to turn to the reports on major finds to discover examples of the more extensive and reliable applications of laboratory examination, or to such periodic publications as Tzu-jan k’o-hsüeh-shih yenchiu [Studies in the History of Natural Science], Peking, and Wen-wu pao-hu yü k’ao-ku k’o-hsüeh

[Sciences of Conservation and Archaeology], Shanghai. Although techniques of dating archaeological remains such as thermoluminescence are in use, radiocarbon assessments have played the major role to date. Dendrochronological conversions still continue to follow the DLW (Damon, Long and Wallick) tables of 1972. In using the radiocarbon data, care is required. Sampled materials and their site associations are not always clear, while risky materials such as shell and bone are usually allowed the same status as more reliable charcoal, wood, etc. In the case of wood, however, it is seldom indicated specifically where the sample has been taken (e.g. from heart-wood or sap-wood). Radiocarbon-dated sites that have been reported with merely a single dated sample are treated in the archaeological literature on much the same level as sites with multiple dates, and clusters thereof. Far too often ‘mid-point dates’ are regarded as the actual date! Secondary studies using these data require careful assessment at practically all stages of reading. However, improvements have steadily been taking root: An Chi-min’s recent assessment of the nature of the anomalies attending the Neolithic periodization in South China on the basis of radiocarbon dates (An Chin-min 1989: 123–33), is an indication of current trends towards more cautious interpretative approaches.

Replication experiments involving the reconstructions of kilns, the baking of pottery, reconstructions of smelting furnaces, the casting of bronze vessels of various types in mould-assemblies following known ancient approaches, and other such experimental investigations, employing where possible comparable raw materials, have been conducted in both Mainland China and Taiwan. Very useful information at the technical level has resulted and this has allowed more effective assessments of the archaeological data.

Since the 1950s, and especially in the 1990s, the variety and rate of publication of Chinese archaeological reports has been phenomenal. In this dictionary, only a minute proportion of the available materials is cited directly – precedence has been given to English language sources (translations and secondary works) to enable the general reader to follow up on the thumbnail sketches offered here; of these, one or more items have been chosen – among other considerations – because of the extensive lists of reference materials consulted and recorded in them. For Chinese and Japanese language publications a free translation of titles is given. In the case of mainland Chinese reports where the authorship comprises one or more institutes – a most awkward custom when it comes to the

CHINCHORRO 159

compilation of bibliographies – the practice adopted here is simply to use the term ‘Anon.’.

Kuo Mo-jo: Chung-kuo ku-tai she-hui yen-chiu

[Researches into Ancient Chinese Society] (Peking, 1930); A.W. Hummel: The autobiography of a Chinese historian

(Leiden, 1931); C.S. Gardner: Chinese traditional historiography (Cambridge, MA, 1938); Li Chi and Wan Chia-pao: Ku-ch’i-wu yen-chiu chuan-k’an [Researches into ancient vessels], 5 vols (Taipei, 1964–72); Chang Ching-hsien: Chung-kuo nu-li she-hui [Chinese slave society] (Peking, 1974); Chang Kwang-chih: Shang civilization (New Haven, 1980); Lu Pen-shan and Hua Chüeh-ming: ‘T’ung-lü-shan Ch’un-ch’iu lien-t’ung shu-lu ti fu-yüan yen-chiu’ [Reconstructional researches into the Ch’un-ch’iu period smelting furnaces of T’ung- lü-shang], WW 8 (1981), 40–5; Anon.: Ch’in-ling erh-hao t’ung-ch’e-ma [The bronze horse and chariot No. 2 of the Ch’in Mound] (Peking, 1983); Anon.: Ch’in-shih-huang- ling ping-ma yung-k’ang [The terracotta warriors pit of the Ch’in-shih-huang-ti mound], 2 vols (Peking, 1988); An Chih-min: ‘Hua-nan tsao-ch’i Hsin-shih-ch’i te 14C tuantai ho wen-t’i’ [Problems attending the early Neolithic periodization in South China on the basis of radiocarbon dates], TSCYY (1989), 123–33; Huo Wei: ‘P’ing Ao Mi’Hsin k’ao-ku-chia-p’ai’ [A critical assessment of the New Archaeology school in Europe and America], SCWW 1 (1992), 8–13.

NB

chinampa Aztec term for a highly productive system of raised-field intensive agriculture practised along the shallow lakeshore in central Mexico (and elsewhere), whereby rich organic muck from the lake bottom was dug up to build a network of rectangular plots. Canals between the plots provided drainage and allowed access by canoe. Chinampas were primarily associated with the AZTECS (in the Postclassic period) but may also have been constructed in TEOTIHUACAN times (the Classic period).

P. Armillas: ‘Gardens in swamps’, Science 174 (1971) 653–704.

PRI

Chinchorro Culture of northern coastal Chile and far southern coastal Peru, between c.4000 and 1000 BC. These were the only South American people to develop artificial MUMMIFICATION: internal organs were removed, sticks inserted along the limbs to make a rigid body, the muscles plumped out with grass; the body was then covered with clay, painted and given a mask of human hair. Not all Chinchorro bodies were given this treatment, but males, females and children in roughly equal numbers were mummified in this way.

B. Bittman: ‘Revision del problema Chinchorro’, Chungara-Arica 9 (1982), 46–79; B.T. Arriaza: Beyond

160 CHINCHORRO

death: the Chinchorro mummies of ancient Chile

(Washington, D.C., 1995).

KB

Ch’ing-lien-kang (Qingliangang) see TA-WEN-

K’OU

Ch’i-shan (Qishan) see WESTERN CHOU

chi-squared test One of a number of ways of examining the ‘fit’ between two or more sets of DATA, or one set and a theoretical MODEL, when the data consist of the numbers of objects that fall into various categories, for example the numbers of artefacts of different types on two or more sites. Tests of a dataset against a model are known as GOODNESS-OF-FIT tests; comparisons of datasets

give rise to CONTINGENCY TABLES.

S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 70–6; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 115–25.

CO

Choga Mami Prehistoric site in eastern central Iraq, at the edge of the Mesopotamian plain. Excavations during the 1960s revealed strata of the late SAMARRA period (c.5000 BC) containing ceramics known as Choga Mami Transitional; this discovery is important since the upper strata at TELL ES-SAWWAN, the classic Samarra site, have been eroded away. The ‘Transitional’ ceramics resemble early UBAID pottery from sites in southern Iraq, such as Eridu and Hajji Muhammed, perhaps indicating that the origins of the Ubaid culture are to be found in the Samarra period. The late Samarra settlement at Choga Mami, as at Tell Songor in the Hamrin Basin, consists primarily of grid-planned multi-room buildings; like Tell es-Sawwan, it was contained within an enclosure wall.

Preliminary reports by J. Oates in Sumer 22/25 (1966, 1969) and Iraq 31/34 (1969, 1972); J. Oates: ‘Choga Mami’, Fifty years of Mesopotamian discovery, ed. J. Curtis (London, 1982), 22–9.

IS

Choga Mami Transitional see SAMARRA

Choga Zanbil see ELAM

Cholula Large site in Puebla, Mexico, occupied since Preclassic times but best known for the role it played in the Postclassic period (c.AD 900–1521). Cholula has been identified as a centre of the QUETZALCOATL cult, and its enormous main temple-pyramid, with episodes of Classic-period

TALUD-TABLERO construction, is now surmounted by a Catholic church. Postclassic Cholula is also associated with the manufacture and wide distribution of a brightly-coloured, polychrome ceramic known as the ‘Mixteca-Puebla’ style.

I. Marquina, co-ord.: Proyecto Cholula, Serie Investigaciones 19 (Mexico, 1970).

PRI

Choris culture see NORTON TRADITION

Chorrera Series of related fishing and agricultural village cultures in coastal Ecuador during the Formative Period (c.3000–500 BC) whose ceramic style was traded and copied throughout Ecuador and may have influenced early ceramic styles, including the coastal CHAVÍN ones, of northern Peru. These cultures were instrumental in the development of long-distance trade networks to procure exotic stones and other items (including metal) for the emerging elites.

C. Zevallos Mendez: ‘Informe preliminar sobre el Cementerio Chorrera, Bahia de Santa Elena, Ecuador’,

Revista del Museo Nacional 34 (1965–6), 20–7; K.O. Bruhns: ‘Intercambio entre la costa y la sierra en el Formativo Tardío: nuevas evidencias del Azuay’,

Relaciones culturales en el area ecuatorial del Pácifico durante la Epoca Precolombina, ed. J.-F. Bouchard and M. Guinea (Oxford, 1989), 57–74.

KB

Chou dynasty (Zhou dynasty) see CHINA 2;

EASTERN CHOU; WESTERN CHOU

Choukoutien Complex cave site near Beijing, China, where in 1927 Davidson Black found hominid fossils which he named Sinanthropus Pekinensis (‘Peking Man’). The fossils have more recently been identified with HOMO ERECTUS although they differ from the early African examples. The lower deposits are now thought to date from c.4–500,000 BP. Unfortunately many of the original fossils were destroyed during the Second World War and only casts remain. The associated archaeological remains for this period resemble the developed Oldowan (see OLDUVAI) chopper/flake industries, although the ACHEULEAN, biface-based technology had by that point existed for nearly one million years in Africa.

Choukoutien is also noted for early evidence of the use of fire, although no identifiable hearths have been found, unlike those claimed for the roughly contemporary site of Terra Amata in France. The Upper Cave has yielded fossil hominids dating from 20–30,000 BP, which, whilst

clearly modern, are said not to resemble modern Chinese.

H.L. Shapiro: Peking man (London, 1976); Jia Lanpo and Huang Weiwan: The story of Peking man (Oxford, 1990).

PG-B

Chou-yüan (Zhouyuan: ‘the plains of Chou’) Archaeologically rich area in China, c.70 km (east–west) by 20 km (north–south), which embraces mainly modern Fu-feng, Chi’-shan, Feng-hsiang and Wu-kung. Large numbers of inscribed bronzes (many from storage pit burials) figure prominently among the various finds from numerous sites in the area. However, the name ‘Chou-yüan’ has become associated with the excavations around Feng-ch’ü-ts’un, near Ch’i- shan-hsien, where two pits in the precincts of palace (or, temple?) remains radiocarbon dated to 1295–1241 BC have yielded over 17,000 ORACLE BONES, 292 of which were inscribed. These artefacts not only indicate the practice of SCAPULIMANCY by the Chou people but also shed light upon the nature of Chou civilization before it subjugated the SHANG city-state in 1122 BC. See also CHINA 2

and WESTERN CHOU.

Ch’en ch’uan-fang: Chou-yüan yü Chou-wen-hua [Chouyüan and the Chou culture] (Shanghai, 1988).

NB

chron see PALAEOMAGNETIC DATING

Ch’u (Chu) Major Chinese state which flourished in the EASTERN CHOU period (771–255 BC), the legendary origins of which are ascribed to the reign of Ch’eng Wang of Chou (c.1100 BC), at which time it was named Ching. It was eventually extinguished by the CH’IN polity in 253 BC. At the height of its power, the state of Ch’u extended from eastern Shen-hsi to the lower Yangtze Valley and from the north well into Ho-nan and northern Anhui thence southwards as far as the Tung-t’ing Lake region in southern Hu-pei and northern Hu-nan.

Ch’u, along with WUR and YÜEH, was regarded as a more or less ‘barbarian’ entity outside the pale of the MIDDLE STATES. In terms of material culture, however, it was a highly cultured region with very advanced levels in mining technology, metallurgy, weaving and embroidery, woodworking and joinery, lacquerware, music, calligraphy, various writings and poetry. The bulk of Eastern Chou literary remains have been unearthed from various Ch’u sites. Poetry (rhymed metric verse) plays a leading role in the compilation of many of the bronze inscriptions (especially those from the state of Ts’ai under Ch’u suzerainty); while the Ch’u silk

CH’Ü-FU 161

manuscript from Ch’ang-sha, includes sections of rhymed text which are among the longest unearthed to date. Very impressive finds such as the

LUAN tomb, the TSENG HOU YI tomb, the HSI-

CH’UAN, HSIA-SSU tombs, the Pao-shan Tomb No. 2, and the well-known Western Han period MA- WANG-TUI Tomb No. 1, along with such recent discoveries of the mining complexes at T’UNG-LÜ- SHAN, JUI-CH’ANG, and Nan-Ling, demonstrate the fact that Ch’u and several of the states under its control, comprised one of the most highly cultured regions of Ch’un-ch’iu and Chan-kuo times.

N. Barnard: ‘The origin and nature of the art of Ch’u – a necessary prelude to assessments of influences from the Chinese sphere into the Pacific’, Proceedings of the First New Zealand International Conference on Chinese Studies

(Hamilton, 1972), 1–47; Li Hsüeh-ch’in: Hou-ma mingshu [The Hou-ma oaths of allegiance texts] (Shanghai, 1976); ––––: Eastern Zhou and Qin civilizations, trans. Chang Kwang-chih (New Haven, 1985).

NB

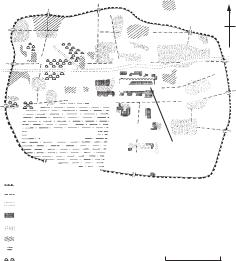

Ch’ü-fu (Qufu) Ancient city site in Shan-tung, China, which was the capital of LU, the territory enfeoffed to Po-ch’in, son of Tan, Duke of Chou, who, as tradition tells us, acted as regent during the

K’ung-lin

(ii)

(i)

(iv) (iii)

Present-day town of Ch’ü-fu

Eastern Chou wall Eastern Chou roadways Eastern Chou waterway Areas of pounded earth Areas of habitations Industrial areas

Eastern Chou city gates Burial areas

N

Palace/ temple area

(i)Wang-fu-t’ai

(ii)Yao-p’u

(iii)Hsi-pei-chiao

(iv)Tou-chi-t’ai

01 km

Figure 12 Ch’ü-fu Eastern Chou walled city of Ch’ü- fu (the capital of the kingdom of Lu), showing features of the city revealed in the 1977-8 excavations. Source: T.F. Munford: Burial patterns of the Chou period: the location and arrangement of cemeteries in North China, 1000-200 BC (Ph.D. thesis, Australian National University, 1985), fig. 6.

162 CH’Ü-FU

minority of Ch’eng Wang, the second king of the newly-established feudal kingdom of Chou which followed upon the SHANG conquest (1122 BC). Ch’ü-fu was also the birthplace of Confucius, who was supposedly also buried here. According to the Shih-chi [The memoirs of the historian], the burial of Confucius was to the north of Lu-ch’eng [Ch’ü- fu]; the tumulus still marked as his tomb lies several hundred metres north of the ancient wall. The site-area is centred around the villages of Chou-kung-miao and Hsiao-pei-kuan; the latter two having been the loci of earlier excavations.

The excavators seek to date some burials (M44, M57, and M35) in the Wang-fu-t’ai cemetery area in the western side of the ancient city from as early as Early Western Chou (1122–1001 BC) but, as well demonstrated by T.F. Munford (1985: 41–55), among other factors, the close similarities of the burials and funerary furnishings generally with those of the SHANG-TS’UN-LING cemetery site do not allow a dating much earlier than Ch’un-ch’iu times (771–481 BC).

Anon.: Ch’ü-fu Lu-kuo-ch’eng [The ancient city of Ch’ü- fu of the state of Lu] (Ch’i-nan, 1982); T.F. Munford:

Burial patterns of the Chou period: the location and arrangement of cemeteries in North China, 1000–200 BC (Ph.D. thesis, Australian National University, 1985).

chullpa Burial house or tower, characteristic of the central and southern Andean highlands.

chultun Underground cistern, usually bellshaped with a narrow mouth, found around domestic settlement in the LOWLAND MAYA area and used for storage of water or food.

D. Puleston: ‘The chultuns of Tikal’, Expedition 7 (1965) 24–9; P.A. McAnany: ‘Water storage in the Puuc region of the northern Maya lowlands: a key to population estimates and architectural variability’, Precolumbian population history in the Maya lowlands, ed. T.P. Culbert and D.S. Rice (Albuquerque, 1990) 263–84.

PRI

Chung-yüan (Zhongyuan; ‘central plains’) Region in central China largely embraced by the adjoining areas of the provinces of Ho-nan, Shenhsi, and Shan-hsi; comprising the confluence of the Huang-ho (‘Yellow River’) Basin with those of the Wei-shui and the Fen-ho. Long regarded as the very cradle of Chinese civilization, it has also been referred to as the ‘nuclear area’ and roughly coincides with the territories of the MIDDLE STATES of Chou times. With the rapid and extensive rate of archaeological discovery over the last three decades, however, and the application of radiocarbon dating (see CHINA 2), this concept has been

modified. It now seems that in the earliest periods the Chung-yüan was only one of several major cultural regions each with indigenous roots extending appreciably into high antiquity. Some, such as TZ’U-SHAN and related cultures in southern Ho-

pei, PEI-LI-KANG in Ho-nan, HO-MU-TU, in

Shang-tung, TA-P’EN-K’ENG, Taiwan (incorporating also the southeast coastal areas of China), variously date back to at least 5000 BC, a few even earlier. Thus up to the historical level (c.2000–1500 BC), increasing attention has been given to the regional developments of the several major Neolithic cultural regions and the variant characteristics of each, while the nature and extent of cultural interplay between them is gradually being clarified. However, from historical times in China, essentially the age of metallurgy and writing, the centrifugal nature of the development of Chinese civilization with its spread from the MIDDLE STATES (i.e. the major states under Chou suzerainty centred in the Chung-yüan) outwards into the peripheral ‘barbarian’ regions, where regional modifications embodying local cultural concepts intermingled with the incoming Chung-yüan influences, has become much clearer. At the same time, the entry of alien influences into the outermost of the peripheral ‘barbarian’ regions is to be noted.

Su Ping-ch’i and Yin Wei-chang: ‘Kwang-yu k’ao-ku- hsueh wen-hua ti chu-hsi-lei-hsing wen-t’i’ [Problems regarding the classification of archaeological cultural regions] WW 5 (1981), 10–17; Chang Kwang-chih: The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven, 1986).

NB

Chu-shu-chi-nien (Zhushujinian) see BAMBOO

ANNALS.

Ch’u silk manuscript (Ch’u-tseng-shu, Chuzengshu) see CHINA 3

‘Cimmerians’ see TIMBER-GRAVE CULTURE

circumscription theory Theory that explains how cultural development is influenced by environmental constraints. The theory was first put forward by Robert Carneiro (1970) in an attempt to explain the origins of the state in the Andes. He argued that communities relying on the farming of narrow valleys for their subsistence were effectively ‘circumscribed’, i.e. a point could easily be reached at which no further land was available for exploitation. This circumscription, combined with population growth, generates conflict between different settlements and thus encourages the development of chiefdoms and subordinate,

tribute-paying communities. According to Carneiro’s theory, the process of territorial conflict provided a continuous stimulus to the development of the state in coastal Peru.

In collaboration with the Egyptologist Kathryn Bard, Carneiro takes a similar approach to the question of the rise of the state in the Nile valley (Bard and Carneiro 1989). They suggest that five principal factors were involved: a concentration of food resources (both in the earlier Predynastic for hunting and fishing and in the late Predynastic for cereal crops); the circumscription of the Nile valley by the desert on either side; increasing population pressure; gradual change in society; and the development of warfare. A sixth crucial factor produced a situation somewhat different to that in the Andes – the concept of the Egyptian divine ruler, which Carneiro believes to have contributed to the final integration of a set of chiefdoms which might otherwise have been continually at war.

R.L. Carneiro: ‘A theory of the origin of the state’, Science 169 (1970), 733–8; ––––: ‘Political expansion as an expression of the principle of competitive exclusion’, Origins of the state: the anthropology of political evolution, ed. R. Cohen and E.R. Service (Philadelphia, 1978), 205–23; K. Bard and R.L. Carneiro: ‘Patterns of predynastic settlement: location, social evolution, and the circumscription theory’, CRIPEL 11 (1989), 15–23.

IS

Cîrna Mid-second millennium Bronze Age cremation cemetery near the Danube in Oltenia, Romania, consisting of c.500 urns buried in about 200 pits about 1m deep. Many of the urns and accompanying vessels (bowls and cups), are impressed and incised with tendril-like designs and arcade or swag-like motifs, often terminating in spirals. Associated with the urns were a series of similarly decorated schematic bell-shaped figurines (c.20cm high), apparently of women wearing dresses.

V. Dumitrescu: Necropola de incineratie din epoca bronzului de la Cîrna (Bucharest, 1961).

RJA

CIS and the Baltic states This region, essentially the European part of the ex-USSR plus Siberia, presents a huge range of archaeological sites, cultures and natural landscapes. Two huge plains – the Russian (East European) and West Siberian, separated by the Ural mountains – make up the western part of the Russian territory. The Altai mountains flank the West Siberian plain in the south. The eastern part consists of the Central Siberian Plateau, Central Yakut Plain and the sys-

CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES 163

tem of mountain ridges, plateaux and uplands in southern and eastern Siberia and the far east. The region includes the largest rivers of Eurasia draining to the Arctic Ocean (the Lena, Ob/Irtysh, Northern Dvina); Pacific Ocean (the Amur); Caspian Sea (the Volga); Black Sea (the Dniepr) and Baltic Sea (the Western Dvina, Neva). The climate is markedly continental, with cold winters (below 50°C in Yakutia) and mild or warm summers. The greater part of Russian territory is taken up by the tundra and forest vegetation zones. A treeless steppe corridor stretches from Southern Russia via Northern Caucasus and South Urals into southern Siberia.

1 Prehistory. The earliest evidence of hominids in the region is provided by the lower levels of AZYKH CAVE in the Caucasus, palaeomagnetically dated to >735,000 years ago. The archaic stone assemblages at the site of KOROLEVO (on the upper Tisza River in the Western Ukraine) are geologically dated to the Mindel-Günz interglacial (780–730,000 years ago). A group of sites with archaic stone inventories, including pebble tools and scrapers, have been discovered in the loess sections in the south Tadjikistan. The oldest site (Kouldoura) has been found in a buried soil below the BrunhesMatuyama geomagnetic boundary, c.735,000 years ago (Ranov 1993).

The Caucasus was intensively settled during the MOUSTERIAN epoch (c.110,000–40,000 BP), as is clear from the cave-sites of Azykh, KUDARO and many others. Mousterian sites are also located near Volgograd (Sukhaya Mechetka), near Kursk (Khotylevo) and in a few other areas of European Russia, as well as in Moldova and in the Ukraine (the Crimean cave sites of KIIK-KOBA, AK-KAYA and others). At the site of STAROSL’YE the skeleton of an anatomically modern human was found within the Mousterian layer.

During the Upper Palaeolithic (c.40,000–15,000 BP), a network of dwelling sites developed in European Russia, Ukraine and Moldova, notably in the basins of the Middle Don, Middle Dniepr and Dniestr. The earliest sites of the KOSTENKIBORSHEVO group on the River Don (belonging to the Streletskian tradition) retain elements of the Mousterian. A fully developed Upper Palaeolithic tradition (Kostenkian) emerged between 24,000 and 21,000 BP.

In the 1930s, Russian archaeologists identified substantial structures made of mammoth bones at a number of Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Russian Plain: Kostenki 1, stratum 1, Kostenki 11 stratum 1, Kostenki 4 and others. The quality of evidence at these sites invites sophisticated analysis; for

164 CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

Millennia /BCAD |

C |

U |

|

|

L |

T |

U |

R |

|

E |

S |

RussC |

|

Epochs |

-W.C. Europe |

South |

Lith. |

ZDvin |

|

|

N–E |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Russia |

LBAStrokedPottery |

LBAUpperD |

|

|

Peri-Baltic |

Diakov.Pozn |

|||

1 |

|

|

|

Tim G |

|

LBA |

|

||||||

1 |

|

|

Prag-P. |

Kurg |

|

|

Spk. |

|

|

||||

|

|

Przew |

Sa |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

0 |

|

|

Sc |

|

Za |

|

|

|

|

Textile |

|

|

|

IA |

Halls |

|

|

ScA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Laus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

BA |

Tr |

|

Cata |

Rzucz |

N-B |

|

|

Cord W |

|

Fa |

||

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

CoW |

|

Pit-G |

Usviaty |

|

S |

P |

|

V |

||||

4 |

|

LP |

Tripolye |

|

DnG-Str-Don |

|

|

|

|

CW |

PrV |

||

3 |

MesolithicNeolithic |

TBK |

|

|

Dubit. |

|

|

|

|

Ly |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sperrings |

|||||||

|

BalkanE |

Neolithic |

|

|

|

Narva |

VolUp. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

B-D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

Epipalaeolithic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Swiderian |

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yudinovian |

|

|

|

|

||

16 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kostenkian |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gorodtsovian |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

Palaeolithic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

31 |

Upper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

32 |

|

|

|

|

|

Streletzkian |

|

|

|

Spitzinian |

|

||

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mousterian |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

instance Olga Soffer (1985) has used faunal analysis in an attempt to distinguish the sites in terms of seasonality and social hierarchy. Complicated burials indicative of social stratification were found at the site of SUNGHIR in Central Russia, while the cave of KAPOVA in the Southern Urals proves the existence of Palaeolithic cave art basically similar to that of the Franco-Cantabria region.

Upper Palaeolithic sites first appeared in Siberia no later than 30,000 years BP (Tseitlin 1979). At that time, the Palaeolithic complex spread north of the Polar Circle, as is evidenced by the sites on the Pechera River (Konivets 1976). After about 15,000 BP, large dwelling-sites practically disappeared from central and southern Russia. However, from c.11,000–10,000 BP there are numerous seasonal camps of reindeer hunters in the ice-free areas of northern and northwestern Russia, notably in the catchments of Upper Dniepr, Upper Volga, and Western Dvina – for example, Nobel, Pribor.

Between 10,000 and 6000 BP various groups of hunter-gatherers can be defined in the region, and these are traditionally classified as MESOLITHIC. In Russian archaeology the term ‘Mesolithic’ implies cultural assemblages left by groups of foragers in an environment of post-glacial forests and steppes. The lithic inventories suggest a degree of cultural continuity with regard to the Late Palaeolithic – the main innovations concerned settlement and subsistence. The sites tend to gravitate to the inshore lagoons in the coastal area and to lakes further afield, reflecting the exploitation of a wide variety of forest, lake and estuarine wild-life resources. Some of the sites (e.g. KUNDA) were of considerable size and were used on a permanent or semi-permanent basis. Large Mesolithic cemeteries were discovered

Table 11 CIS and the Baltic states Chronological table for the Upper Palaeolithic to Iron Age.

Key

BA = Bronze Age; B-D = Bug-Dniestrian; C = Cherniakhov Culture; Cata = Catacomb Grave Culture; CW = Comb Ware; C o W = C o r d e d Wa r e ; D n - D o n = D n i e p r - D o n e t s i a n ; F a = Fatyanovo: Rzucz-Rzuczewo; Gu = Huns; Halls = Hallstatt; IA = Iron Age; Kurg = Kurgans; Laus. = Lausitzian; LBA = Late Bronze Age; LP = Linear Pottery; Ly = Lyalovo; N-B = North Bielorussian Culture; P = Piestina; Pit-G = Pit-Grave Culture; Ponz. = Pozniakov Culture; Prag-P. = Prag-type Pottery; PrV = Protovolosovo; Przew = Przeworsk Culture; S = Sarnate; Sa = Sarmatians; Sc = Scythians; ScA = Agricultural Scythians; Spk = Sopki; Str-G. = Strumel-Gastyatin; TBK = Funnel Beaker Culture; TimG = Timber Grave Culture; Tr = Trzciniec Culture; Up Vol = Upper Volga Culture; V = Volosovo; Za = Zarubincy Culture