A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf‘cultural lag’, the important point is that the process was not instantaneous.

N. Barnard and Satö Tamotsu: Metallurgical remains of ancient China (Tokyo, 1975); ––––: ‘Bronze casting technology in the peripheral “barbarian” regions’, BMM 12 (1987), 3–37.

NB

culture-historical theories see CULTURE

HISTORY

culture history Term used to describe a broad range of archaeological approaches that use historical explanatory principles to examine changes in culture. The origins of cultural-historical archaeology are to be found in the late 18th century, when the word culture (which had once been applied simply to the practice of agriculture) began to be used by German ethnologists to describe rural or tribal ways of life in contrast to the ‘civilized’ socioeconomic activities of city-dwellers (e.g. Klemm 1843–52). By the late 19th century, scholars such as E.B. Tylor (1871) and Eduard Meyer (1884–1902) were writing about culture in its broader, more modern sense of ‘a particular form, stage or type of intellectual development or civilization’.

Trigger (1989: 163) argues that the systematic definition of a whole sequence of interacting groups of ‘archaeological cultures’, such as the CYCLADIC or TRIPOLYE cultures, did not fully emerge until the nationalistically-motivated attempts of the German archaeologist Gustaf Kossinna (1911) to establish the origins of the INDO-EUROPEAN peoples. From this point until the emergence of NEW ARCHAEOLOGY, the idea of prehistory and history as long sequences of spatial and temporal mosaics of cultures was firmly established. Whereas 19thcentury scholars had primarily viewed cultural change in terms of an evolution from primitive to advanced forms of culture and technology, the cultural-historical archaeologists of the early 20th century began to describe and analyse changes in the archaeological record in terms of the emergence and movement of different (but not necessarily more ‘advanced’) cultural groupings. Needless to say, such archaeologists did not self-consciously proclaim any programmatic ‘culture history’ approach to archaeology – the term itself was rarely used until the advent of New Archaeology (see below).

The work of such pioneering archaeologists as Gordon Childe (1925), James Ford and Gordon Willey (1941), working within the culture history framework, did a great deal to establish meaningful chronological foundations for European and

CULTURE HISTORY 185

American archaeology. There were, however, also numerous misuses and abuses of the idea of culturehistory, such as the work of hyper-diffusionists (see DIFFUSIONISM) and nationalists (including Kossinna). Culture historians are also sometimes accused of assuming the dominance of cultural norms (shared sets of rules and expectations; see

NORMATIVE EXPLANATIONS). It is of course via

norms, expressed through material culture, that archaeologists are able to identify distinct cultures in the archaeological record in the first place – but in some cultural-historical explanations this can lead to a down-playing of cultural dissention, cultural dynamics and the actions of individuals. It can also lead to an unwarranted equating of material culture with non-material culture facies such as language, religion and ritual, and political structure (as an example of the dangers of this approach, see

‘BEAKER PHENOMENON’).

In the 1960s, the term ‘culture history’ began to be employed in a more derogatory manner to describe ‘traditional’ attitudes that were in direct opposition to the study of ‘culture process’ as espoused by New Archaeology (or PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY). New Archaeologists argued that scientific and anthropological principles should be applied to archaeological evidence in the search for an understanding of how past societies functioned – often in terms of SYSTEMS THEORY. This allowed them to downplay the traditional cultural historian’s favoured mechanisms of cultural change and diversity (i.e. cultural and technological invention, migration of peoples, diffusion) in favour of concepts such as the multiplier effect and systemic adaption to environmental change (see SYSTEMS THEORY). Certain proponents of the New Archaeology also emphasized the search for universal laws of culture process over and above the importance of cultural diversity and difference – although some scholars (e.g. Hogarth 1972) continued to argue that archaeology was essentially a culture-historical discipline.

The reaction against processual archaeology from the late 1970s led some archaeological theorists to re-examine the culture-historical tra-

dition. For example, CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY

returned to a more historical and ‘particularist’ stance, although it attempted to understand the relationship between culture and the material culture of the archaeological record in a more sophisticated fashion than in traditional culturehistorical studies (e.g. Hodder 1982).

G.F. Klemm: Allgemeine Cultur-Geschichte der Menschheit, 10 vols (Leipzig, 1843–52); E.B. Tylor:

Primitive culture (London, 1871); E. Meyer: Geschichte des

186 CULTURE HISTORY

Alterthums, 5 vols (Stuttgart, 1884–1902); G. Kossinna: Die Herkunft der Germanen (Leipzig, 1911); V.G. Childe:

The dawn of European civilization (London, 1925); J.A. Ford and G.R. Willey: ‘An interpretation of the prehistory of the eastern United States’, American Anthropologist 43 (1941), 325–63; A.C. Hogarth: ‘Common sense in archaeology’, Antiquity 46 (1972), 301–4; I. Hodder: The present past: an introduction to anthropology for archaeologists (London, 1982); B.G. Trigger: A history of archaeological thought (Cambridge, 1989), 148–205.

IS

culture process see PROCESSUAL

ARCHAEOLOGY

cuneiform Earliest known writing system, which emerged in SUMER during the early 3rd millennium BC. Probably evolving originally from simple tokens, the cuneiform script rapidly established itself as the principal medium for diplomatic communication and economic transactions throughout the Ancient Near East, until it was eventually replaced by the alphabetic Aramaic script (see ARAMAEANS). The initial breakthrough in the decipherment of the cuneiform script was made in the 1830s when Henry Rawlinson studied Darius I’s trilingual inscriptions at BISITUN.

D. Schmandt-Besserat: ‘From tokens to tablets’, Visible Language 15 (1981), 321–44; J.N. Postgate: ‘Cuneiform catalysis: the first information revolution’, ARC 3 (1984), 4–18; J. Oates and S.A. Jasim: ‘Early tokens and tablets in Mesopotamia: new information from Tell Abada and Tell Brak’, WA 17 (1986), 348–62; C. Walker: Cuneiform (London, 1987); J.N. Postgate: Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history (London and New York, 1992), 51–70; D. Schmandt-Besserat: Before writing (Austin, 1992); H.J. Nissen: Archaic book-keeping: early writing and techniques of the economic administration in the Ancient Near East (Chicago, 1993).

IS

cup marks Simple cup-shaped depressions that were pecked out on megaliths, natural boulders and outcrops in northern Britain and certain other areas of Europe. When the cup mark is enclosed by one or more concentric circles the motifs are known as ‘cup-and-ring’ marks. In these cases, the concentric circles are sometimes traversed by a radial groove, often referred to in the literature as a ‘gutter’, or may be incomplete. Cup marks are difficult to date, but seem to have been made during the later Neolithic, the Bronze Age (especially) and possibly the Iron Age.

RJA

parallel linear banks with external ditches, forming ceremonial ‘avenues’. The avenues are often closed at both ends by a continuation of the bank and ditch. Over 30 British examples are now known, the longest being the Dorset Cursus in southern England which extends about 9 km across the chalk downlands. The banks of the Dorset Cursus are about 90 m apart and incorporate two long barrows. The other cursus monuments vary greatly in size (typically under 1 km in length and below 45 m in width), but often incorporate or seem related to other Neolithic ritual enclosures (henges, square ‘mortuary enclosures’) or funerary monuments. The term ‘cursus’ derives from 18th-century speculation that they may be the remains of racetracks; modern interpretations tend to favour the idea of processional avenues, perhaps linking up complex ritual landscapes. Excavation suggests that they were built from around 3000 BC onwards (the Dorset Cursus is associated with PETERBOROUGH ware); not all were built in one phase – excavations have shown that some have been extended, while others are composed of a series of separately constructed sections.

R.J.C. Atkinson: ‘The Dorset Cursus’, Antiquity 29 (1955), 4–9; R. Bradley: The Dorset cursus (London, 1986).

RJA

Cuzco Capital of the INCA empire, located in a high valley in the Peruvian Andes. Although there had been an occupation in the city area since the Early Horizon, imperial Cuzco was defined as the sacred centre of the Inca realm by Pachacuti Inca Yupanki (crowned AD 1438), the founder of the Inca empire. Pachacuti sponsored a major building programme and many of the remaining Inca buildings can be ascribed to his architects. Inca Cuzco was laid out in the form of a puma and was a sacred place where ordinary people were not permitted to live. Among the most notable structures were the Coricancha (the Temple of the Sun, now under the church of Santo Domingo), with its garden of gold and silver plants and animals; the Haucaypata, the huge central square where the ruler watched public rituals and made (public) solar observations from a stone platform (an usnu); and the ‘fortress’ of Sacsayhuaman above the city, with its famous cyclopean walls. Most of these buildings and spaces are now much destroyed and modern construction tops the much finer Inca foundations.

J. Rowe: An introduction to the archaeology of Cuzco

(Washington, D.C., 1944); S. Niles: Callachaca: style and status in an Inca community (Iowa, 1987).

cursus Neolithic monuments consisting of two |

KB |

cybernetics Body of scientific theory that attempts to understand and measure the control mechanisms that regulate and characterize mechanical, electronic, biological and other systems. A core feature of cybernetics is the analysis of communication and information flows between different elements within a system. Although the term cybernetics is used rarely in archaeology, certain core concepts have been imported as part of

SYSTEMS THEORY.

RJA

Cycladic culture Culture which developed on the Cyclades Islands in the southern Aegean during the phase known as the Early Bronze Age or Early Cycladic (c.3300–2000), characterized by a series of fine figurines made from the local marble. Most of the evidence of the culture is from its – much looted – cemeteries, which are relatively small and which suggest a degree of social differentiation: the richest graves may contain more than one figurine and multiple marble bowls, together with painted pottery or even special items such as the silver diadem found at Dokathismata.

Throughout their history the cultures of the islands seem to have been linked culturally and to some extent economically, at first by canoe traffic – canoes are shown on early pottery – and later by sailing ships. The islands also offered the mainland important sources of obsidian (Melos) in the Neolithic and, later, metals. The Early Cycladic cultural assemblage seems to have evolved out of the local Neolithic, as expressed at SALIAGOS and KEPHALA. The Early Cycladic is generally divided into at least two phases: the Early Cycladic I (ECI) or Grotta-Pelos culture (3300–2700) and the Early Cycladic II (ECII) or Keros-Syros culture (2700–2300). Many scholars recognize an Early Cycladic III or Kastri phase (ECIII), lasting a few centuries after the end of the ECII.

The known ECI settlements are generally small and unfortified. There was only limited use of metal during the ECI, and obsidian continued to provide many of the tools. The phase is characterized by a form of cylindrical lidded vessel (or pyxis) with finely incised decoration, by fine marble bowls and ornaments, and especially by a series of very simple but finely made schematic marble figurines. These ‘violin’ or ‘fiddle’ figurines (so-called after their shape) are flat, headless and largely plain except for the incised lines that occasionally delineate the pubic region etc. Most of the marble-work has been recovered from the cemeteries of simple slab-built cist-tombs. A particularly rich set of burials, assumed to date from near the end of ECI and

CYCLOPEAN MASONRY 187

known as the ‘Plaistos group’, presents a distinctive assemblage of grave-goods: marble collared vases (or kandela) with a bulbous body and pedestal, marble bowls, and a form of figurine that is more three-dimensional and detailed than usual.

During ECII settlements seem to be located in more defensible positions, and they gain fortifications. From the middle of the 3rd millennium the Cycladic culture began to influence sites on the Greek mainland, and Cycladic material is found in Early Minoan II and III contexts. There are developments across the whole range of material culture (summarized in Renfrew 1991), but the most dramatic is the development of the marble figurines described below. In the late Early Cycladic settlements developed in coastal locations, and during the succeeding Middle Bronze Age phase these became the sites of true ports and towns

– an example is the site of Akrotiri on THERA. From the Middle Bronze Age, the influence of Minoan, and subsequently Mycenaean, civilizations increased – illustrated most dramatically by the Theran wall-paintings. After these early Mediterranean civilizations disappeared, the Cyclades became absorbed in the wider Mediterranean cultural world and lost their early cultural and artistic distinctiveness.

Cycladic figurines. The classic expression of the early Cycladic culture is a series of figurines produced during ECII, simple but not schematic like the ECI examples. Most are less than 50 cm in height, though there are monumental examples (e.g. Renfrew 1991, pl 103). The figurines conform to strict conventions: carved facial detail is restricted to the prominent nose (eyes and hair were sometimes painted on); the arms are folded over stomach/chest; the legs are defined by a groove or full incision rather than being fully separated; there is little attempt to convey volume by carving fully in the round. Many of the sculptures may also follow a convention of proportion (Renfrew 1991, ch. XI).

C. Renfrew: The emergence of civilization: the Cyclades and the Aegean in the third millennium BC (London, 1972);

––––: The Cycladic spirit (London, 1991).

RJA

Cyclopean masonry Type of walling that consists of large polygonal blocks of stone, either shaped or in their natural form, carefully fitted together to provide a continuous – but not necessarily smooth – wall. (By contrast, MEGALITHIC architecture is composed of large unshaped or only slightly shaped stones which may rest against or on top of each other, but which rarely give

188 CYCLOPEAN MASONRY

a continuous surface without the aid of drystone infilling). Cyclopean masonry is named after Cyclops, the mythical one-eyed giant of Greek legend, whom the ancient Greeks supposed to have constructed the massive MYCENAEAN fortifications in the Cyclopean style. The term is now applied elsewhere in the world – for instance, to describe the

Figure 13 cylinder seal Banqueting scenes depicted on a Sumerian cylinder seal of the Early Dynastic Period. Source: H. Crawford: Sumer and the Sumerians

(Cambridge University Press, 1991), fig. 6.6.

walls of Inca sites such as CUZCO.

RJA

cylinder seal Stone cylinder carved with relief decoration, which was rolled across wet clay items (particularly cuneiform documents or jar-stoppers) in order to indicate their genuineness or prove their ownership. Developed as an alternative to stamp seals, particularly in Mesopotamia during the late 4th to 1st millennia BC, it was eventually replaced by the increasing use of stamp-seals and ring-bezels. The complex variations in size, style and design make cylinder seals extremely useful in terms of iconographic analysis and the dating of the archaeological features in which they are found.

A.M. Gibson and R.D. Biggs: Seals and sealing in the Ancient Near East (Malibu, 1977); B. Teissier: Ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals from the Marcopoli collection (Berkeley, 1984); D. Collon: First impressions: cylinder seals in the Ancient Near East (London, 1987).

IS

Cyrenaica see AFRICA 1

D

Dabða, Tell el- (anc. Avaris) Egyptian settlement site in the eastern Delta, immediately to the south of modern QANTIR, where the Ramessid city of Piramesse grew up from the late 14th century BC onwards. The ancient town, temples and cemeteries of Avaris, covering an area of about two square kilometres on a natural mound partly surrounded by a lake, have been excavated by the Austrian archaeologist Manfred Bietak since 1966. The work has been spread over a number of different sites within the region of Tell el-Dabða, comprising a complex series of phases of occupation ranging from the 1st Intermediate Period to the 2nd Intermediate Period (c.2150–1532 BC). The deep stratigraphy at Tell elDabða has allowed the changing settlement patterns of a large Bronze Age community to be observed over a period of many generations. Bietak’s excavations indicate that the Egyptian settlement at Avaris was transformed into the capital of the HYKSOS in the 2nd Intermediate Period (1640–1550 BC), when it effectively became the centre of a SyroPalestinian colony within the Delta.

In the early 1990s the principal focus of attention in Bietak’s work was the substructure of a substantial building (probably a palace) of the Hyksos period, located at Ezbet Helmi at the western side of Tell el-Dabða. The site has achieved particular prominence because of the discovery, in 1991, of numerous fragments of early 18th-dynasty wallpaintings in the ancient gardens adjoining the structure. These depictions include scenes of ‘bullleaping’ closely resembling those excavated from the Middle Bronze Age palace at Knossos as well as from two sites in the Levant (Kabri and Alalakh). The paintings may indicate that people of Aegean origins were living within Avaris itself.

M. Bietak: Avaris and Piramesse: archaeological exploration in the eastern Nile delta (London and Oxford, 1981); W.V. Davies and L. Schofield, eds: Egypt, the Aegean and the Levant: interconnections in the second millennium BC

(London, 1995); M. Bietak: Avaris (London, 1996).

IS

Dabar Kot Large settlement mound, about 70 ha in area, located in the Thal river in the Loralai

valley of northern Pakistan. Limited excavations were conducted by Aurel Stein in 1929, followed by the surface surveys of Walter Fairservis and Sadurdin Khan in the 1950s. The site incorporates evidence for a very long occupation, from the 3rd millennium BC to the 1st millennium AD. Artefacts from the site include pre-Harappan and Mature Harappan material (see INDUS CIVILIZATION), including such painted ceramics as pre-Harappan Kili Ghul Muhammad (see QUETTA) and Periano wares and Mature Harappan black-on-red pottery. Other artefacts from pre-Harappan and Mature Harappan levels include terracotta figurines and copper and flint tools. Materials from early historic levels include iron tools and Buddhist figurines; a large unexcavated structure in the upper levels of the site may be the remains of a Buddhist religious complex.

W.A. Fairservis: ‘Archaeological surveys in the Zhob and Loralai District, West Pakistan’, Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 47 (1959), 277–478.

CS

Dabban see AFRICA 1

Dabenarti see MIRGISSA

Dahshur Egyptian cemetery of pyramids and mastaba-tombs, forming part of the southern end of the Memphite necropolis, which was used for royal burials during the Old and Middle Kingdoms (c.2649–1640 BC). The two earliest attempts at true pyramids (the Red Pyramid and the Bent Pyramid) were built at Dahshur by Sneferu (c.2575–2551 BC); the Bent Pyramid has retained more of its stone outer casing than any other pyramid. There are also three Middle Kingdom pyramids at Dahshur, belonging to Amenemhat II, Senusret III and Amenemhat III; these make up the northern extension of the royal cemetery that grew up around the 12th-dynasty capital, Itj-tawy, probably located near EL-LISHT about 25 km to the south.

J. de Morgan: Fouilles à Dahchour, 2 vols (Vienna, 1895–1903); A. Fakhry: The monuments of Sneferu at

190 DAHSHUR

Dahshur, 2 vols (Cairo, 1959–61); D. Arnold: Der Pyramidenbezirk des Königs Amenemhet III in Dahschur I (Mainz, 1987).

IS

Daima Settlement mound 5 km from the Nigeria–Cameroon frontier and 45 km south of the shore of Lake Chad in northeastern Nigeria, excavated by Graham Connah in 1965–6. The site is located on flat clay plains subject to annual flooding and known as ‘firki’ from their propensity to crack during the dry season. The mound, 250 × 170 m in size, was sectioned by means of main cutting VIII, which was 50 × 6 m at ground level and 11.5 m deep. The sequence produced eight radiocarbon dates in the range 2520–890 BP, but they are in part problematical because of stratigraphic inversions and imperfect agreement between results based on charcoal and those based on animal bones. A division of the apparently continuous occupation into three phases (I: 550 BC–AD 50, II: AD 50–700, and III: AD 700–1150) is suggested by plotting all the dates against depth and drawing a best-fit curve through them. In Graham Connah’s opinion, phase III represents a more affluent society with a more complex culture; nonetheless it continued the same distinctive exploitation pattern as before. Adopting an explicitly ecological model, he has labelled this ‘the firki response’. Very probably those who put it into effect (the ‘So’ people) were Chadic speakers, who only gradually came under Kanuri control from the 14th century AD onwards.

G. Connah: Three thousand years in Africa: man and his environment in the Lake Chad region of Nigeria (Cambridge, 1981).

PA-J

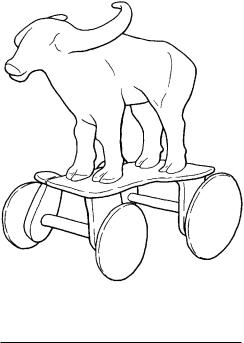

Daimabad Chalcolithic mound, about 50 ha in size, located on a tributary of the Godavari river in Maharashtra, India. The excavations of Deshpande (1958–9), Nagaraja Rao (1974) and S.A. Sali (1975–7) have documented five main phases: Savalda (c.2200–2000 BC), a locally defined Late HARAPPAN phase (c.2000–1800 BC), Daimabad (c.1800–1600 BC), MALWA (c.1600–1400 BC) and JORWE (c.1400–1000 BC), each distinguished by changes in ceramic styles, architecture and funerary remains. The most dramatic discovery from Daimabad was a unique undated hoard found by a local farmer in 1974. This consisted of four massive bronze sculptures: an elephant, a rhinoceros, a buffalo and an ox-drawn cart with human occupant. Dhavalikar (1982: 366) has suggested that these bronzes probably date to the Late Harappan period and may have been imported.

Figure 14 Daimabad Copper buffalo from the Daimabad hoard (Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay).

M.K. Dhavalikar: ‘Daimabad bronzes’, Harappan civilization, ed. by G.L. Possehl (New Delhi, 1982) 361–6; S.A. Sali: Daimabad 1976–79 (New Delhi, 1986).

CS

Dakhla Oasis Fertile region in the Libyan Desert, about 300 km to the west of modern Luxor, where the remains of circular stone huts indicate that the area was settled by sedentary groups as early as the EPIPALAEOLITHIC period (c.9000–8500 BP; McDonald 1991). A village of the Old Kingdom (c.2649–2150 BC) and a group of associated 6thdynasty mastaba-tombs have been excavated near the modern village of Balat (Giddy and Jeffreys 1980; Giddy 1987), and a cemetery of the 1st Intermediate Period (c.2150–2040 BC) has been discovered near the village of Amhada. These remains suggest that the pharaohs had already gained control of areas beyond the confines of the Nile valley by the end of the Early Dynastic period. Later ruins include a Ramessid temple of the goddess Mut (c.1130 BC), near Azbat Bashindi, a Greco-Roman necropolis (c.332 BC–AD 395), a temple of the Theban triad (Amun, Mut and Khonsu) at Deir elHagar, a temple of Thoth at el-Qasr, Roman tombs at Qaret el-Muzawwaqa, and a Roman settlement and temple at Ismant el-Kharab (Hope 1994).

H.E. Winlock, ed.: Dakhleh Oasis (New York, 1936); L.L.

Giddy and D.G. Jeffreys: ‘Balat: rapport préliminaire des fouilles à ðAyn Asil, 1979–80’, BIFAO 80 (1980), 257–69;

––––: Egyptian oases: Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra and Kharga during pharaonic times (Warminster, 1987); M.M.A. McDonald: ‘Technological organization and sedentism in the epipalaeolithic of Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt’, AAR 9 (1991), 81–109; C. Hope: ‘Excavations at Ismant el-Kharab in the Dakhleh Oasis’, EA 5 (1994), 17–18.

IS

Dalton Tradition dating from c.8500 to 7900 BC, evidence of which has been found throughout much of the southeastern United States, with particularly dense concentrations of sites in the central Mississippi River valley. Dalton toolkits are characterized by distinctive, nonfluted projectile points which are lanceolate in outline with a concave base. Also represented are hafted, bifacially flaked Dalton adzes. Differences between Dalton toolkits and those of earlier PALEOINDIAN cultures are probably attributable first to the transition from Late Pleistocene to Holocene environmental conditions and secondly to the exploitation of different kinds of plants and animals.

A. Goodyear: ‘The chronological position of the Dalton Horizon in the southeastern United States’, AA 47 (1982), 382–95; D. and P. Morse: Archaeology of the central Mississippi Valley (New York, 1983) 71–97.

RJE

Damascus see ISLAMIC ARCHAEOLOGY

Damb Sadaat Pre-Harappan mound site located near modern Quetta in northern Pakistan near the strategic Bolan Pass linking South to Central Asia. In the 1950s Walter Fairservis identified three chronological phases stretching from c.3400 to 2500 BC, according to calibrated radiocarbon dates. The first phase (Period I), comprising remains of mud-brick architecture, painted ceramics, including Kechi Beg polychrome and red paint wares and QUETTA black-on-buff ware, bone implements and a stone-blade industry, shows affinities with the earlier site of Kili Ghul Muhammad. In period II, plain and painted Quetta wares dominated the ceramic assemblage; a ceramic seal, and copper dagger and fragments were also recovered. Quetta wares declined in period III and were replaced by Sadaat black-on-red or buff wares.

W.A. Fairservis: ‘Excavations in the Quetta Valley, West Pakistan’, APAMNH 45 (1956), 169–402; S. Asthana:

Pre-Harappan cultures of India and the Borderlands (New Delhi, 1985).

CS

DANEBURY 191

dampmarks see SOILMARKS; AERIAL

ARCHAEOLOGY

Danangombe (Dhlo Dhlo) Large Khamiperiod settlement, with a population in excess of 5000, which was the capital of the ruling Rozwi dynasty in Zimbabwe from the 1690s onwards. The first ruler was the famous Changamire Dombolakonachingwango who is credited with

destroying the PORTUGUESE TRADING FEIRA of

Dambarare and forcing the Portuguese to retreat to the Zambezi. The ruling dynasty in Venda today were originally Rozwi, or closely related to them, and they moved south of the Limpopo River in the 1690s during this initial Rozwi expansion. Danangombe was mentioned in a Portuguese document in 1831, but it may have been abandoned shortly before then. Because it continued well into the historic period, Danangombe forms an important bridge between archaeological data and Shona and Venda ethnography. The settlement organization found here serves as a model that can be applied to older sites such as GREAT ZIMBABWE.

D.R. MacIver: Mediaeval Rhodesia (London, 1906); G. Caton-Thompson: The Zimbabwe culture: ruins and reactions (Oxford, 1931); D. Beach: The Shona and Zimbabwe 900–1850 (Gwelo, 1980); T.N. Huffman: Snakes and crocodiles: power and symbolism in ancient Zimbabwe

(Johannesburg, 1996).

TH

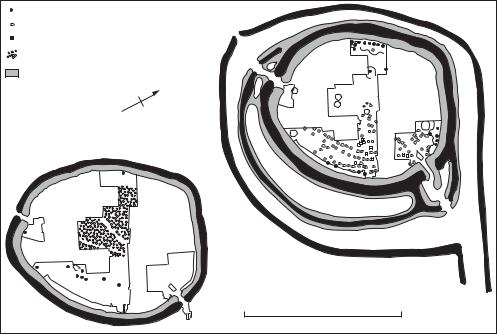

Danebury Iron Age hillfort of c.550–100 BC located in Hampshire, England, which from 1969 was subjected to an intensive series of excavations led by Barry Cunliffe. The defences consisted of a massive timber-revetted inner rampart and ditch encircled by a later and slighter rampart and ditch, and an outer ditch – giving a total area of 16.2 ha. The excavations revealed a heavily used and to some extent planned interior filled by: a central road running across the fort between the two entrances, and later subsidiary roads; circular ‘houses’ (6–9 m diameter), either built of stakes and wattle and daub, or of continuous plank walls; concentrations of storage pits; and small shrines. Like other Wessex hillforts, Danebury was found to contain numerous settings of four or six posts, which are usually interpreted as raised granaries. The low ratio of houses to storage facilities suggests that Danebury may have functioned more as a form of regional storehouse than as a settlement; this interpretation is supported by the analysis of the plant remains, which suggests that the grain was collected from a number of different growing environments. (The complex question of the control of this ‘storehouse’

192 DANEBURY

houses |

|

4-posters |

|

shrines |

|

pit clusters |

|

ramparts |

|

N |

|

EARLY |

|

|

LATE |

0 |

250 m |

Figure 15 Danebury Plans of the two major phases of the Danebury hillfort: the 6th century BC (left) and the 4th century BC (right). Source: B. Cunliffe: Anatomy of an Iron-Age hillfort (London, 1983), figs 29–31.

is critically addressed in Bradley, 1984.) At the same time Danebury seems to have been in use throughout much of its history – contradicting a model for Iron Age hillforts as temporary refuges in times of crisis.

R. Bradley: The social foundations of prehistoric Britain

(London, 1984), 135–9; B.Cunliffe: Danebury: an Iron Age Hillfort in Hampshire (London, 1984–91), 5 vols; critical review of vols 1 and 2 by J. Collis in PPS 51 (1985), 348–9; B. Cunliffe: ‘Danebury: the anatomy of a hillfort exposed’,

Case studies in European prehistory, ed. P. Bogucki (Boca Raton, 1993), 259–85.

RJA

Danger Cave Site near Great Salt Lake, Utah, in western North America, which provided a 10,000-year sequence of short-term occupations, forming the basis for the so-called Desert Culture, a way of life limited by and adapted to the extreme environmental conditions of the Great Basin. Based partly on ethnographic analogy with the Shoshone and partly on inference from the artefactual and contextual data derived from the excavation of Danger Cave, this long-stable lifestyle of small nomadic bands intensively exploiting a desert environment provides a sharp contrast

with the BIG GAME HUNTING TRADITION of the

earlier period.

J.D. Jennings: Danger Cave, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology 14, (1957).

RC

Danzantes see MONTE ALBAN

Dapenkang see TA-P’EN-K’ENG

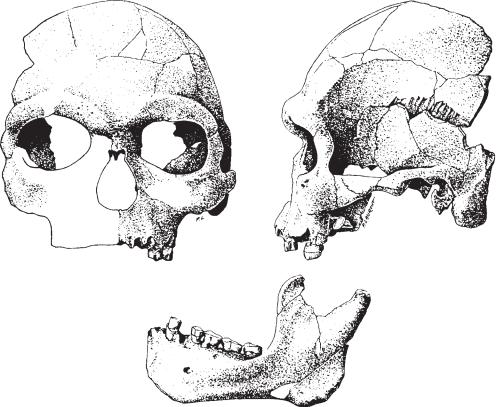

Dar es-Soltane II Cave on the Moroccan coast 6 km southwest of Rabat (excavated by André Debénath from 1969 onwards), 200 m from the cave of Dar-es-Soltane I (excavated by Armand Ruhlmann in 1937–8). Five metres of deposit at the front of the cave produced traces of human occupation in layers 2 (Neolithic), 3 (Epipalaeolithic) and 6 (ATERIAN). The remains of at least three hominids (one adult partial skull and mandible, one adolescent mandible, and one juvenile calvaria) were found over a quarter-square-metre area beneath a sandstone block in layer 7 (marine sands resting on bedrock) and are regarded as being associated with the Aterian. The skull was studied by Denise Ferembach, who came to the conclusion that it represented a robust

SAPIENS with characteristics intermediate between

those of JEBEL IRHOUD and the MECHTA-AFALOU

population associated with the IBEROMAURUSIAN. In her view, therefore, the remains from this cave testify to a local evolutionary transformation from archaic to anatomically modern man in northwest Africa. R.G. Klein comments that ‘the skull exhibits no features that distinguish it significantly from most modern human skulls, yet the population it represents inhabited Morocco at the same time that Neanderthals occupied Europe’. Five more individuals of the same type (four adult and one juvenile) are known from Aterian layers at three other sites on the Moroccan coast: El Harhoura I (Grotte Zouhrah), Témara (Grotte des Contrebandiers), and Tangier (Mugharet elAliya). The remains from the last two sites were originally identified as pre-Neanderthal or Neanderthal; but, as J.J. Hublin comments, these

DAR ES-SOLTANE II 193

hominids always display a ‘very robust masticatory apparatus and a pronounced megadonty’ and such features could explain why the first discoveries were considered to be ‘more primitive than they actually are’.

A. Debénath: ‘Découverte de restes humains probablement atériens à Dar es Soltane (Maroc)’, CRASP, série D, 281 (1975), 875–6; D. Ferembach: ‘Les restes humains de la grotte de Dar-es-Soltane 2 (Maroc) campagne 1975’,

Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris

3 (1976), 183–93; K.P. Oakley et al.: Catalogue of fossil hominids, Part 1: Africa, 2nd edn (London, 1977); A Debénath et al.: ‘Position stratigraphique des restes humains paléolithiques marocains sur la base des travaux récents’, CRASP, série II, 294 (1982), 1247–50; A. Debénath et al.: ‘Stratigraphie, habitat, typologie et devenir de l’Atérien marocain: données récentes’, L’Anthropologie 90 (1986), 233–46; R.G. Klein: The human career (Chicago and London, 1989); A. Debénath: ‘Les Atériens du Maghreb’, DA 161 (1991), 52–7; J.J. Hublin:

0 |

5 cm |

||

|

|

|

|

Figure 16 Dar-es-Soltane II The partial skull and mandible of an adult hominid found in layer 7 at Dar-es-Soltane II (drawing by P. Laurent). Source: A. Debénath et al.: L’Anthropologie 90 (1986), fig. 2.

194 DAR ES-SOLTANE II

‘Recent human evolution in northwestern Africa’

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, series B, 337/1280 (1992), 185–91.

PA-J

data Archaeological data consist of measurements made on archaeological objects (using the term in the widest possible sense, to include for example artefacts, features, assemblages, sites), as well as counts of such objects. Measurements include physical measurements (e.g. lengths and weights), scientific determinations (e.g. chemical analyses), other descriptive characteristics (e.g. colour), and assignments of objects to categories (i.e. types). Each measurement or characteristic is known as a VARIABLE; a set of variables measured on a collection of objects is known as a dataset. A dataset in tabular form, usually with rows representing objects and columns representing variables, is called a data matrix. The fundamental problem of using statistics in archaeology is QUANTIFICATION, i.e. the reduction of collections of objects to datasets. Some objects, such as building plans, are so complex that their data must take account of internal relationships (e.g. between rooms) as well as measurements and counts.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 93–114; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 8–21; C. Dallas: ‘Relational description, similarity and classification of complex archaeological entities’, Computer applications and quantitative methods in archaeology 1991, ed. G.R. Lock and J. Moffett (Oxford, 1992), 167–78.

CO

data matrix see DATA

data reduction see REDUCTION OF DATA

data set see DATA

dating techniques Scientifically-based dating techniques have a number of prerequisites. There must be a time-dependent variable, which ideally is accurately and precisely measureable and its time dependence must be well-known (e.g. the quantity of 40Ar relative to 40K in POTASSIUM-ARGON DATING defined by radioactive decay and hence the half-life of 40K). There must be a point which can be defined as being ‘time zero’ (for example, the point of death of an animal in RADIOCARBON

DATING, the firing of a pot in THERMOLUMINES-

CENCE, or the solidification of a lava flow in

POTASSIUM-ARGON DATING). This time zero and

the sample dated must be relatable to the archaeo-

logical event for which the age is actually required. In radiocarbon dating, for example, an articulated bone in a grave can readily be associated with the burial event, but mature wood charcoal fragments in the fill of a ditch are of little or no value in dating the cutting of the ditch. Similarly a piece of volcanic rock in an archaeological level will provide a date only for the formation of the rock, not its incorporation within the sediment, but archeological finds sandwiched between two volcanic layers must lie within the limits defined by these terminus results: whether these provide a sufficiently detailed chronology will depend on the circumstances. One further prerequisite is that no factor affects the intrinsic value of the time-dependent variable, other than the time dependence itself. In URANIUM-

of calcite, for example, the sample must be a closed system, preventing migration of uranium in or out of the calcite once it has formed, and in RADIOCARBON DATING pre-treatment techniques are used to remove any contaminating carbon acquired post mortem.

The techniques used in archaeological dating can be broadly categorized as based on radioactive decay or spontaneous fission (ALPHA RECOIL,

FISSION TRACK, POTASSIUM-ARGON, RADIOCALCIUM, RADIOCARBON, URANIUM-SERIES); based on climatic change (CALCITE BANDING, DENDROCHRONOLOGY, ICE CORES, OXYGEN ISOTOPE,

CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY, VARVES); based on

particular properties of materials (AMINO

ACID RACEMIZATION, ARCHAEOMAGNETISM,

CATION-RATIO, ELECTRON SPIN RESONANCE,

FLUORINE UPTAKE, NITROGEN LOSS IN BONE, PALAEOMAGNETISM, OPTICALLY STIMULATED LUMINESCENCE, TEPHROCHRONOLOGY,

THERMOLUMINESCENCE), and based on diffusion

processes (OBSIDIAN HYDRATION, NITROGEN PROFILING AND SODIUM PROFILING). Not all of these

in fact have an inherent time-dependence; some (e.g. ARCHAEOMAGNETISM) require calibration by other techniques, or at best provide only a very rough indication of chronology (e.g. flourine uptake). A number of other techniques (not listed here) have time ranges applicable to geological problems.

Scientific dating techniques quote an error term which is the precision (reproducibility) at the 1 level i.e. there is a 68% chance, if the result is accurate (i.e. unbiased), that the true age will lie between –1 and +1 of that quoted. Equally there is a 32% chance (i.e. nearly 1 in 3) that it will not. The probability increases to 95% for the range –2 to +2.

G. Faure: Principles of isotope geology, 2nd edn (New York, 1986); M.J. Aitken: Science-based dating in archaeology