A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

N

42 41

J

40

0

IFE 295

sections 2.3 terracotta, pottery

bone

stone

iron

12 m

quarried |

|

|

I |

|

|

|

|

2.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

2.2 |

|

E |

|

|

G |

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

17 |

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

C |

24 |

|

F |

|

|

||

14 |

15 |

34 |

|

|

|

||

|

34 |

37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.1 |

|

|

|

nails |

D |

l s |

|

A |

|

|

||

|

n a i |

|

|

quarried |

|

|

|

L i n e |

o f |

b a n k |

44 |

|

|||

|

|

|

52 |

53

7?

2.2

H

2.3

2.3

k |

|

|

n |

|

|

a |

|

|

b |

|

|

f |

|

|

o |

2.3 |

|

e |

2.1 |

|

n |

||

2.1 |

||

i |

||

L |

|

B

12 |

11 |

|

|

|

54 |

|

1051 |

2.1

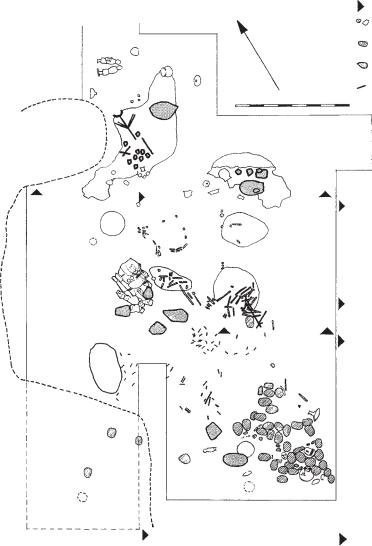

Figure 22 Ife Ife culture, plan of the main artefact concentrations at the Obalara’s Land site (labelled A–J), including terracotta heads modelled in naturalistic and schematic styles. Source: P.S. Garlake WAJA 4 (1974).

emotionally charged area’ subject to ‘extraacademic pressures and sanctions’. It is said to be home to 401 deities, the last being the ruler or Oni, who claims descent from Oduduwa the founder of the dynasty. In 1943, Kenneth Murray established that there were at least 120 shrines in the city, most of them originally situated in groves, small patches of forest often with sacred ‘peregun’ trees. Many of the groves have been destroyed by modern urban

development, one of the few to survive being at Obameri, excavated by Oliver Myers in the 1960s. At that time the grove measured 60 m2 and the shrine 25 m2; it is typical of many in Ife, in that the fragments of terracotta found were judged to have been ‘dug up and reburied’ annually as part of the festivities for the god, and a radiocarbon date of 220 ± 100 BP (AD 1730) confirmed that some of these activities were quite recent. Something of an

296 IFE

archaeologist’s nightmare, the practice of deliberate reburial renders the distinction between primary and secondary contexts more than usually difficult and necessary. Thus, at a site on Odo Ogbe street, where there are also much older deposits, Ekpo Eyo found that a terracotta head in a ‘scoop’ of earth with a radiocarbon date of 320 ± 95 BP (AD 1630) had itself been reburied. The ‘artefact concentrations’ excavated by Peter Garlake at Obalara’s Land, ‘an extra-ordinarily diverse range of objects to a considerable extent purposefully arranged’ (Garlake 1974: 143), included a group of already damaged terracottas covered with red clay. They are interpreted as part of a shrine, with four radiocarbon dates in the range 760–480 BP (AD 1190–1470). The practice of ‘burial and reburial’ therefore goes back to what has been termed the ‘Classical’ period of Ife.

By the term ‘Classical’, W.B. Fagg and Frank Willett, who first coined it, meant to refer to a ‘type period’ in the history of the city characterized by ‘naturalistic bronzes’ and terracottas, but it has subsequently been taken to include edge-laid potsherd pavements, and it is now more usual to refer to the ‘potsherd pavement’ period as marking the high point of the city’s early development. Thurstan Shaw and Garlake list 25 radiocarbon dates currently available from seven excavated sites in Ife, of which Shaw attributes 13 to this period, with in addition 10 preand two post-pavement dates (Shaw 1981: figs 2–4). Most important of the prepavement sites is Orun Oba Ado, excavated by Willett, with five dates in the range 1390–960 BP (AD 560–990). Pavement period ‘one component’ sites, apart from Obalara’s Land, include Woye Asiri and Lafogido, excavated by Garlake and Ekpo Eyo respectively. Excluding one anomalous result, there are four dates from Woye Asiri in the range 815–545 BP (AD 1135–1405) and one from Lafogido of 840 ± 95 BP (AD 1110). Also important is Ita Yemoo, excavated by Willett in 1957–63, but here, as Garlake puts it, the dates cover a long period and are ‘not internally consistent’: three underlie pavements and two (associated with terracotta sculptures) overlie them, whereas two came from ‘pit or well fills’. Taking all the dates together and calibrating them, Shaw concluded that the ‘potsherd pavement period’ in Ife extended from about AD 1100 to 1450.

The nature of the potsherd pavements can be most clearly discerned at Obalara’s Land and Woye Asiri (Garlake 1974: figs 3–4; 1977: figs 4–8) – not an accident, if we accept the author’s claim that, apart from his own work, ‘not a single comprehensive or detailed report on any excavation in Ife’ has

up to now been published. The pavements were frequently constructed around complete buried pots (interpreted by Garlake as libation jars) and semicircular cut-aways were convincingly shown to represent altars. The overall orientation of the pavements at the two sites was consistent enough to justify the claim that they represented deliberate urban planning. At Lafogido 15 pots surmounted by terracotta animal heads were arranged in a rectangular formation around a potsherd pavement, which suggested to Ekpo Eyo that this was a primary occurrence, a royal temple or tomb. A primary context has also been claimed for the terracotta sculptures overlying the potsherd pavements at Ita Yemoo. Two of the pavements were found underlying the town wall sectioned by Willett, suggesting that the walled city encompassed a much smaller area than that occupied when the ‘potsherd pavement period’ was at its height. A date of 600 ± 100 BP (AD 1350) for one of the pits beneath the wall provides a terminus post quem for its construction.

Among the elements making up the corpus of ‘Classical’ Ife art, it is the terracotta sculptures and ‘naturalistic bronzes’ that have attracted the most attention, ever since Léo Frobenius unearthed them at the Olokun grove in 1910–11. The terracottas are more numerous and varied, including a composite group from the Iwinrin grove which is claimed to be the ‘largest single’ such object ever made in Africa. The majority of terracottas are naturalistic, but there is no doubt that schematic representations were made at the same time, since both have been found together at Obalara’s Land and are shown side by side on one of the libation jars from the site (Garlake 1974: fig. 6 and pl.xlvi). As Shaw emphasizes, the ‘naturalistic bronzes’ (which are actually of copper or leaded brass) are few in number, < 30, of which 18 were recovered from the Wunmonije compound in 1938–9 and seven from Ita Yemoo in 1957. Fagg and Willett suggested that they represent royal or chiefly personages and that they were made for a ‘royal ancestor cult, probably associated with some form of divine kingship’ (Fagg and Willett 1962: 361). They may have been used in connection with second burial (‘ako’) ceremonies. In view of their stylistic homogenity, Shaw (1981: 112) expressed the opinion that they might be ‘the work of one generation, even perhaps of a single great artist’. It is now possible to test this proposition, and to assess the relationship between the ‘bronzes’ and the other elements making up the ‘Classical’ Ife complex, because seven TL dates have been obtained on their clay cores at Ita Yemoo and Wunmonije (Shaw 1981: fig 5). The dates from

Wunmonije are in the range 510–415 BP (AD 1440–1535), whereas two pieces from Ita Yemoo come to 585 ± 70 and 530 ± 50 BP (AD 1365 and 1420) respectively. Taken together the dates suggest that the ‘bronzes’ occur towards the end of the ‘Classical’ period in Ife. By contrast, the earliest casting in Ife style is now known to occur at Tada on the Niger > 200 km north of the city, where the so-called ‘seated figure’ has a TL date of 625 ± 60 BP (AD 1325). A ‘standing figure’ from the same site has a date of 585 ± 55 BP (AD 1365) but whereas its affinities are uncertain the seated figure has been described as the ‘supreme masterpiece of Ife founding’ (Willett and Fleming 1976: 139).

Other elements of material culture associated with the ‘Classical’ period include tubular blue glass beads (‘segi’), manufactured locally as shown by numerous fragments of crucibles found in excavated contexts and widely exported to other parts of West Africa, and quartz stools. Horton indeed suggests (1979: 88, 107–8) that the symbolic role of these items – particularly the beads which form an essential component of Yoruba royal crowns (‘ade’)

– may have been greater than that of the naturalistic sculptures. Iron working also played an important role, as shown by its ritual representation in the form of a > 50 kg pear-shaped lump in the shrine of Ogun Ladin, artefacts excavated at Obalara’s Land, and slag and tuyères found at Woye Asiri. The evidence of local manufacture at the last site contrasts sharply with the fact that up to now no such positive indications have been found for the ‘bronzes’ for which the city is justly famous. Research questions arising from the still fragmentary record of Ife’s archaeological and historical past include the following:

Reasons for Ife’s rise and decline. In the model proposed by Horton (in which ‘causal priority’ is given to geographic, technological, and economic factors rather than to politics and religion), Ife’s rise to power in the period from AD 900 to 1450 and its subsequent decline are due to changing patterns of trade between the forest and coastal areas on the one hand and the Sahara and savanna on the other. Ife originally controlled a ‘central trade route’ but was subsequently cut off and bypassed by the successor states of Benin and Oyo. The Tada ‘bronzes’ mentioned above are relics of the once flourishing trade route from Ife to Gao. Graham Connah (1987: 148–9) warns however that the ‘external stimulus hypothesis remains untested . . . until we know far more about the archaeology of the first millennium AD within the forest’.

Continuity and discontinuity in Ife’s history. The early centuries of Ife’s history have been termed the ‘pre-

IFE 297

Oduduwa’ period by Ade Obayemi (‘prince of iconoclasts’ as Horton calls him) in an attempt to downgrade the role of the Oduduwa dynasty in the history of the city. If this period is considered to extend up to the time of the building of the town wall, as Obayemi suggests, then clearly it would embrace all the years of Ife’s greatness. Whatever might be thought of this controversial suggestion, the results of the excavations at Obalara’s Land and Woye Asiri have tended to confirm that there are indeed elements of continuity between the early city and the Yoruba ‘spiritual capital’ of today. Thus, the pottery wares recovered include bowls of ‘isasun’ and ‘agbada’ type; two iron artefacts from Obalara’s Land are similar to ‘ogboni staves’ used by ‘Ifa’ diviners (Garlake 1974: fig. 10); and ‘ogboni’ motifs can also be discerned on certain pottery vessels from this site (Garlake 1974; fig. 6). The same vessels also show gagged heads and decapitated bodies, a reminder that human sacrifice at Ife was not forbidden until 1886 (Fagg and Willett 1962: 362).

Ife’s relationship with Nok and Benin. Willett stressed the African-ness of Ife’s artistic achievements (shown in the characteristic body proportions of the ‘bronzes’ and terracottas) in part no doubt as an antidote to Frobenius’s suggestion that the city was a lost Greek Atlantis, and he endeavoured to trace its roots to the NOK culture on stylistic grounds. In view of the chronological gap, others have doubted whether there are adequate reasons for linking the two except ‘in a remote and very generalized way’. There are much stronger grounds in local tradition to link Ife and BENIN. It is said that as late as AD 1888 the heads of the Obas of Benin were brought for burial at Orun Oba Ado, in recognition of the fact that the dynasty sprang from there. Willett’s excavations failed to provide confirmation of this point, but at Obalara’s Land and Woye Asiri a surprisingly large number of artistic motifs were found which did connect them: leopards’ heads, human heads with snakes issuing from the nostrils, ‘cat’s whiskers’ and keloid scarifications, snakes, and rectangular panels behind the altars. The available radiocarbon and TL dates are not inconsistent with the tradition of a link between the two cities, but this and all other aspects of Ife’s early development await further investigation.

F. Willett: ‘Ife and its archaeology’, JAH 1 (1960), 231–48; W. Fagg and F. Willett: ‘Ancient Ife: an ethnographical summary’, Actes du IV Congrès Panafricain de Préhistoire et de l’Etude du Quaternaire, section III, préet protohistoire

(Tervuren, 1962), 357–73; O.Myers: ‘Excavations at Ife, Nigeria’, The West African Archaeological Newsletter 6

298 IFE

(1967), 6–11; 7 (1967), 4–6; M.A. Fabunmi: Ife shrines (Ife, 1969); F. Willett: ‘A survey of recent results in the radiocarbon chronology of Western and Northern Africa’, JAH 12 (1971), 339–70; F. Willett: ‘Archaeology: chapter VIII’, Sources of Yoruba history, ed. S.O. Biobaku (Oxford, 1973), 111–39; E. Eyo: ‘Odo Ogbe Street and Lafogido: contrasting archaeological sites in Ile-Ife, Western Nigeria’, WAJA 4 (1974), 99–109; P.S. Garlake: ‘Excavations at Obalara’s Land, Ife: an interim report’, WAJA 4 (1974), 111–48; F. Willett and S.J. Fleming: ‘A catalogue of important Nigerian copper-alloy castings dated by thermoluminescence’, Archaeometry 18/2 (1976) 135–46; P.S. Garlake: ‘Excavations on the Woye Asiri family land in Ife, Western Nigeria’, WAJA 7 (1977), 57–95; R. Horton: ‘Ancient Ife: a reassessment’, JHSN 9/4 (1979), 69–149; A. Obayemi: ‘Ancient Ile-Ife: another cultural reinterpretation’, JHSN 9/4 (1979), 151–85; T. Shaw: ‘Ife and Raymond Mauny’, Le sol, la parole et l’écrit: mélanges en hommage à Raymond Mauny

(Paris, 1981), 109–35; G. Connah: African civilizations, precolonial cities and states in tropical Africa: an archaeological perspective (Cambridge, 1987).

PA-J

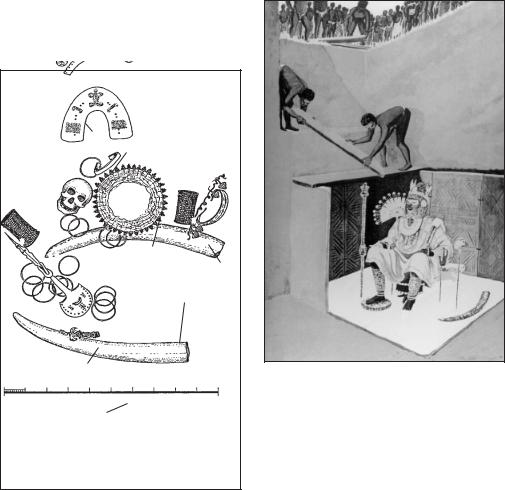

Igbo-Ukwu Town 40 km southeast of Onitsha, southeastern Nigeria, where excavations carried out by Thurstan Shaw in 1959–60 (on behalf of the Nigerian Federal Department of Antiquities) and in 1964 (on behalf of the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan) identified a cultural complex associated with a series of fine coppers and bronzes. The excavations were at three sites, all on land owned by a local family called Anozie, which in order to distinguish them have been christened Igbo Isaiah, Igbo Richard, and Igbo Jonah. Public attention was first drawn to this area in 1938, when Isaiah Anozie recovered a number of bronze artefacts while digging a cistern in his compound, although it subsequently became clear that finds had been made at the other two sites as far back as 1922. Shaw established that the three sites were functionally distinct but also shared many traits in common; hence he regarded them all as belonging to what he termed the ‘Igbo-Ukwu culture’. The results of his excavations were published in meticulous detail in two large volumes in 1970, thanks to a subvention from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations. His principal objective, as he said, was to make the primary data available to others, and his philosophy was to ‘keep separate what is description and observation and what is interpretation’ (Shaw 1977: 109). He published a shorter and more popular account in 1977, and these two works (as well as Shaw’s later papers) provide the essential baseline for any consideration of the finds at Igbo-Ukwu and the controversies which have subsequently surrounded them.

All the sites together produced 685 artefacts of copper and bronze (weighing > 74 kg) of which 110 are counted as major pieces: > 165,000 beads of glass and stone; and 21,784 potsherds, the majority consisting of characteristic ancient ‘Igbo-Ukwu ware’ with deep grooving, protuberant bosses, and patterns reminiscent of basketwork; and other objects, including some iron artefacts and iron slag, three ivory tusks, and fragments of textiles and calabashes. It is the metalwork which has attracted the most attention, on account of what W.B. Fagg called its ‘strange rococo, almost Fabergé-like virtuosity’. Whereas the copper was worked by smithing and chasing, the bronze (actually, leaded bronze with on average 6.5% tin and 8% lead) was cast using a ‘lost wax’ (or, more probably, a ‘lost latex’) technique. The resulting products have seemed to many, as Denis Williams has put it, to constitute ‘an exquisite explosion without antecedent or issue’ (Williams 1974: 119). Apart from the question of the raw materials employed for metalworking and their implications in terms of indigenous versus imported technology, controversy has centred around two topics arising directly from Thurstan Shaw’s work: (1) dating and (2) the possible ethnographic interpretation of these finds. Dating. Shaw originally obtained five radiocarbon dates on the following materials: wood from the stool in Igbo Richard 1100 ± 120 BP; charcoal from Igbo Jonah pit VI 1075 ± 130 BP; charcoal from Igbo Jonah pit IV 1110 ± 110, 505 ± 70, and 1110 ± 145BP. Four of these dates therefore fell in the 9th century AD and one (an ‘odd man out’) in the 15th. Shaw explained that the younger date might well be due to contamination from the modern clay pit above pit IV, and indicated that the balance of probability was very much in favour of a 9th century date. In his view, none of the other evidence contradicted this conclusion; the most difficult point concerned the beads, many of which, in the opinion of Alex du Toit and W.G.N. van der Sleen, must have had an Indian or Venetian origin and been imported, perhaps via Egypt. In the ensuing controversy, summarized by Shaw in 1975, there were both those who defended a younger and an older date (in particular because the latter seemed to confirm the antiquity of the Ibo people) and he himself was ‘caught in the cross-fire between the contending parties’. At the Pan-African Congress in 1983 he was able to announce that he had obtained three more dates from the British Museum, but these were subsequently revised, as follows: wood from the stool in Igbo Richard 940 ± 370BP; charcoal from Igbo Jonah pit IV 1260 ± 310 and 1100 ± 260BP (Shaw 1995a:

1995b). Calibrating the results according to the dendrochronological calender, Shaw concludes that seven of the eight dates indicate that the finds belong to a period between the 8th and 11th centuries AD. Both old and new dates are in very close agreement, and Shaw has expressed the hope that this controversy can now be allowed to ‘die down’ so that attention can be focused on other problems.

Ethnographic interpretation. In his original report, Shaw drew attention to the fact that the finds at Igbo-Ukwu might be interpreted by reference to the ‘Eze Nri’ institution first investigated by M.D.W. Jeffreys in the 1930s. This idea has been taken up and expanded by M.A. Onwuejeogwu and K. Ray. The institution exists both at Agukwu and at Oreri, immediately north of Igbo-Ukwu, and in fact Shaw ascertained that the land on which the sites are located had originally belonged to Oreri. The repository at Igbo Isaiah is therefore interpreted as having been an ‘obu’ or lineage temple used in connection with the title system, and the

IGBO-UKWU 299

burial as that of a priest king or ‘ozo’ titled man. Ray, emphasizing what he calls the ‘communicative uses of material culture . . . within a culturally and historically determined structure of meaning’, suggests that the symbols of lineage authority at Igbo Isaiah served to reinforce the strategy of social control practised by the elders and title-holders, whereas the ‘material metaphor’ of the snake as divine messenger appearing on the copper crown of the ‘Eze Nri’ at Igbo Richard underlined his role as divine representative. The ‘historical metaphor’ of the ‘children of Nri’ (male and female, each bearing characteristic ‘ichi’ scarification marks) is clearly seen on the ‘altar stand’ from Igbo Isaiah. Not everyone is convinced of the utility of these parallels. John Sutton (1991: 149) considers that this line of enquiry ‘encourages a synchronic and on

Crown, IR 337

and IR 343

Pectoral plate, IR 407

Circle of spiral copper bosses set in wood, IR 454

Copper handle for calabash, IR 464

Skull

Tanged copper |

Beaded armlets, |

fan-holder IR 432 |

IR 416 and |

|

IR 417 |

Bronze horseman |

|

hilt, IR 350 |

|

0 |

1 |

metre |

|

Figure 23 Igbo-Ukwu Igbo Ukwu, Igbo Richard: (A) schematic plan of the relative position of objects on or near the floor of the burial chamber, including numerous copper anklets, three tusks and (1) pectoral plate (2) skull

(3) circle of spiral copper bosses set in wood (4) beaded armlets (5) copper handle for calabash (6) tanged copper fan-holder, (7) bronze horseman hilt and (8) crown (B) reconstruction showing the completed burial chamber as it was being roofed in (painting by Caroline Sassoon). Source: Thurstan Shaw.

300 IGBO-UKWU

occasion a sentimental approach’ which ‘tends to emphasize the ritual and ceremonial aspects of art and wealth at the expense of addressing squarely the question of how that wealth would have been amassed’. He therefore opposes ‘the supposition of timeless continuity’ as likely to hinder further progress in understanding Igbo-Ukwu. This discordant note suggest that the ability of these sites to generate controversy is far from exhausted.

T. Shaw: Igbo-Ukwu: an account of archaeological discoveries in eastern Nigeria, 2 vols (London, 1970); D. Williams: Icon and image (New York, 1974); T. Shaw: ‘Those Igbo-Ukwu radiocarbon dates: facts, fictions and probabilities’, JAH 16/4 (1975), 503–17; ––––:

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu: archaeological discoveries in eastern Nigeria (Ibadan, 1977); K. Ray: ‘Material metaphor, social interaction and historical reconstructions: exploring patterns of association and symbolism in the Igbo-Ukwu corpus’, The archaeology of contextual meanings, ed. I. Hodder (Cambridge, 1987), 66–77; V.E. Chikwendu et al.: ‘Nigerian sources of copper, lead and tin for the IgboUkwu bronzes’, Archaeometry 31/1 (1989), 27–36; P. Craddock: ‘Man and metal in ancient Nigeria’, British Museum Magazine 6 (1919), 9; J.E.G. Sutton: ‘The international factor at Igbo-Ukwu’, AAR 9 (1991), 145–60; T. Shaw: ‘Further light on Igbo-Ukwu, including new radiocarbon dates’, Proceedings of the 9th Congress of the Pan-African Association of Prehistory and Related Studies, Jos, 1983, ed. B. Andah, P. de Maret and R. Soper (Ibadan, 1995a), 79–83; ––––: ‘Those Igbo-Ukwu dates again’, NA 44 (1995b), 43.

PA-J

Ihnasya el-Medina see HERAKLEOPOLIS

MAGNA

Impressed ware see CARDIAL WARE

Inamgaon Large Chalcolithic site on the Bhima river in Maharashtra, India, consisting of five mounds spanning the MALWA and early and late JORWE periods (c.1800–700 BC). Excavations have uncovered over 130 structures and 260 burials, as well as evidence for pottery kilns and substantial constructions relating to defence and irrigation, including a large embankment of the early Jorwe period. Domesticates known from the site include rice, wheat, barley, lentil, pea and millets, as well as humped cattle, dog, sheep and goat, and domestic horse. Wild fauna including deer, antelope, mongoose, hare, turtle, and fish were also recovered.

M.K. Dhavalikar et al.: Excavations at Inamgaon, 2 vols (Pune, 1988).

CS

Inca South American cultural group whose empire represents the last great expansionist state in

the Andean region. The Incas were originally one of many small, warring tribes found in the Peruvian highlands after the collapse of HUARI. Under their ninth ruler, who renamed himself Pachacuti (‘earthquake’) when a series of military victories over local rulers led him to usurp the throne, the Inca rapidly expanded across the highlands and then the coast, eventually controlling most of the central and south Andean area and the Ecuadorian highlands. Throughout this area, the Inca introduced their own peculiar ceramic and architectural styles and their official religion, itself invented by Pachacuti to serve the ideological needs of his new empire. Inca architecture, especially the finely-cut stone architecture that typifies many important buildings, has long entranced the western world.

Inca stone working The very fine fitting and often immense stones used in important Inca constructions has been a subject of considerable speculation, much of it risible (i.e. extra-terrestrials or travelling Asians, Africans and Europeans), over the years. A combination of experimental archaeology and architectural analysis has allowed researchers to reconstruct the methods and procedures used in Inca stone work, and to better understand the conceptualization of projects and the organization of labour in the Inca state.

In 1979 Jean-Pierre Protzen, an architect at the University of California, became interested in the subject, and began fieldwork aimed at reconstructing the process from quarrying methodologies to working the stones and erecting structures (buildings, terrace walls, etc.). Work at the largely destroyed Sacsahuaman (the stones from which were moved downhill to reconstruct Cuzco in a European mode) and at unfinished parts of Ollantaytambo indicated that the Inca characteristically worked the top of a block when the block was in place, fitting the stones by a trial and error method and using stone dust as an indication of when to work a block down. Transport of the stones was accomplished by means of chutes, and by dragging stones with the help of wooden sleepers (perhaps), although the huge stones of terrace walls seem to have been quarried on site and moved very little. Protzen’s work indicates that the Inca, like other South American peoples, used relatively simple technologies pushed to their utmost. It reinforces ideas concerning the value of time put into the manufacture of luxury goods, in this case the finely worked stone walls of royal and religious buildings.

J.H. Rowe: ‘Inca culture at the time of the Spanish conquest’, Handbook of South American Indians 2 (1946), 183–330; ––––: ‘The origins of creator worship among the

Inca’, Culture in history: essays in honour of Paul Radin, ed. S. Diamond (New York, 1960); E. Guillén: ‘El enigma de las momias Incas’, BL 5/28 (1983), 29–42; J. Hyslop: Inca settlement planning (Austin, 1990); J. Idrovo: ‘Arquitectura y urbanismo en Tomebamba, Ecuador’, Beiträge zu Allgemeinen Verlagleichenden Archäologi 13 (1993), 254–330; J.-P. Protzen: Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo (Oxford and New York, 1993).

KB

incensario (incense burner, censer) Pottery vessel used to burn incense, usually some kind of tree resin (e.g. Protium copal), and found throughout Mesoamerica in all periods. There are many different varieties and they are often elaborately modelled and painted with figures of costumed deities.

M. Goldstein: ‘The ceremonial role of the Maya flanged censer’, Man 12 (1977), 402–20; J.C. Berlo: ‘Artistic specialization at Teotihuacan: the ceramic incense burner’, Precolumbian art history: selected readings, ed. A. Cordy-Collins (Palo Alto, 1982), 83–100.

PRI

India see ASIA, SOUTH

Indo-European Indo-European is the name given by linguists to a family of languages found across a broad area from northern India and Iran to western Europe, including the Germanic and Romance tongues. These languages can be shown to share certain words, especially the names of certain trees and the words for ‘horse’ and ‘wheeled vehicles’. The way in which these modern languages are related is best explained by their having had a common root language, which at some unknown point spread throughout the ‘IndoEuropean’ area. Various attempts have been made to identify the likely original homeland of the speakers of this archaic Indo-European language – the so-called Proto-Indo-Europeans – although linking linguistic and archaeological evidence is notoriously difficult. One approach to the problem seemed to be to identify the earliest cultures to domesticate horses and to use wheeled vehicles. Partly because the early Bronze Age KURGAN cultures of the Pontic-Caspian steppe qualify on both counts, and, as mobile pastoralists are assumed to have had a propensity for migration or invasion, they have traditionally been regarded as strong contenders.

However, there is no direct evidence that these peoples spoke an Indo-European language, or that they invaded central or western Europe, and this traditional interpretation (fully described and discussed in Mallory 1989), was challenged in 1987 by Colin Renfrew. In a controversial analysis Renfrew

INDUCTIVE AND DEDUCTIVE EXPLANATION 301

suggested instead that the first agriculturalists in the Near East were Indo-Europeans, and that the Indo-European language accompanied the spread of farming from Anatolia, across Europe, after c.6500 BC; a related hypothesis has been advanced by Krantz (1988).

C. Renfrew: Archaeology and language: the puzzle of the Indo-European origins (Cambridge, 1987); critically reviewed in Quarterly Review of Archaeology 9, 1988, by C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky and M. Gimbutas; G. Krantz:

Geographical development of European languages (New York, 1988); J.P. Mallory: In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth (London, 1989); C. Renfrew: ‘They ride horses, don’t they?: Mallory on the Indo-Europeans’, Antiquity 63 (1989), 43–7.

RJA

inductive and deductive explanation Philosophers of science identify two fundamental ways of generating and validating descriptive and explanatory theories about phenomena in the world: inductive explanation and deductive explanation.

Inductive explanations begin with particular observations about the real world. These observations are then used to build the generalizations and links that constitute theories. Archaeologists often use inductive thinking when trying to interpret the evidence that they are gathering from an individual site. For example, archaeologists may notice that an unusual kind of pottery seems to occur repeatedly in a ritual context; they may move from this series of real-world observations to suggest that the pottery is ‘ritual pottery’.

In contrast, deductive explanation begins with theory-building. A series of premises are built up, from which, logically, a particular conclusion must be deduced. From this theory, the archaeologist can derive various hypotheses that must be true if the theory is valid (given that a hypothesis is simply an untested assertion of the relationship between certain aspects of a theory). At this point, the archaeologist can turn to the real world and try to substantiate his or her theory by testing the associated hypotheses against the evidence. If the evidence contradicts the hypothesis, then both the hypothesis and (if the logic is correct) the theory as formulated must be untrue. Because this approach depends upon posing hypotheses and deducing logical relationships, it is often known as the hypothetico-deductive method.

Although these are the two polar approaches to theory building, there are various compromises and extensions. For example, many archaeologists use an essentially inductive form of reasoning to suggest

302 INDUCTIVE AND DEDUCTIVE EXPLANATION

those theories worth careful consideration. They may then analyse the theories, forming hypotheses to describe the nature of the relationship between the theory and the underlying data. At this point, the archaeologist may test these hypotheses against the evidence in a very similar way to the hypothetico-deductive method. If the hypotheses do not survive the test, they are amended until the formulation of the theory accords with the evidence in the most plausible way. Although in archaeology the data available may not allow very thorough testing, this method, sometimes called the analytical inductive approach, combines the practicality of the inductive approach with some of the rigour of the deductive approach.

In some circumstances, it may be possible to test an archaeological theory using statistical methodologies and probability analysis – particularly where those methods have themselves suggested an unusual and interesting relationship between variables in a sample. Essentially, these approaches demonstrate the likelihood of the relationship seen in the sample data having occurred by chance or by sampling error, and thus its significance in interpreting real-world relationships. When statistical tests are used to assess the plausibility of an inductive explanation, the conclusion is sometimes called an inductive statistical (or probabilistic) explanation. (Deductive statistical explanations also exist, but are rarely applicable in the discipline of archaeology.) It is important to stress that tests that prove a significant and strong relationship between variables do not themselves prove an inductive theory – they merely strengthen the argument that the particular correlations observed are unlikely to have happened by chance. For example, a careful statistical analysis of the ‘ritual pottery’ mentioned above might reveal whether the fact that the pottery was found only in the ritual contexts was a statistically significant association; but statistical analysis could never prove that the pottery was used for ‘ritual’ purposes.

The relationship between these modes of enquiry and the use of general or universal laws is discussed further in the entry on COVERING LAWS. See also

THEORY AND THEORY BUILDING.

P.J. Watson et al.: Explanation in archaeology: an explicitly scientific approach (New York and London, 1971); G. Gibbon: Explanation in archaeology (Oxford, 1989).

RJA

inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) Method of quantitative chemical analysis based on the measurement of the spectrum of atomic emission

from a sample excited in an argon plasma. The technique is a development of OPTICAL EMISSION SPECTROMETRY using a high temperature plasma (6000–10,000°K), a more stable and efficient atomization source than an electric arc. It is applicable to metals, ceramics, glass and lithics and will quantify from major down to trace or ultratrace levels in some cases. Samples are required to be in solution and must be dissolved in high purity reagents, normally a mixture of concentrated acids. This operation must be carefully planned to ensure complete dissolution of the sample.

Samples are introduced into the plasma via a nebulizer which disperses the solution as an aerosol (see figure 24). The plasma temperature causes electron energy-level transitions within atoms of the elements in the sample which result in the emission of light at wavelengths characteristic of the individual elements present. It is necessary to measure the intensity of specific wavelengths corresponding to each element being quantified; this can be achieved by rapid scanning of the spectrum, measurement at preset wavelengths or a combination of both. The light intensities are proportional to the element concentrations in the plasma and hence in the solution. The instrument is calibrated using standard solutions containing known concentrations of the elements to be quantified.

The analysis is effectively simultaneous and typically 20 or more elements may be measured in one solution. The technique is applicable to the same range of materials as AAS (ATOMIC ABSORPTION SPECTROPHOTOMETRY) but has several advantages including speed, fewer interferences, linearity of calibration over wide concentration ranges and the ability to measure certain important elements such as sulphur and phosphorus. The earliest applications in archaeology have been on ceramics and glass.

M. Thompson, and J.N. Walsh: Handbook of inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (London, 1983); M.P. Heyworth et al.: ‘The role of inductively coupled plasma spectrometry in glass provenance studies’, Archaeometry 1986 (Athens, 1988), 661–9.

MC

inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICPMS) Method of quantitative chemical and isotopic analysis which combines the features of the two techniques of

AES (INDUCTIVELY COUPLED PLASMA-ATOMIC EMISSION SPECTROMETRY) and mass spectrometry

to produce a versatile trace and ultratrace. Samples, which must be in solution, are introduced into an argon plasma, similar to a conventional ICP, but

INDUS CIVILIZATION 303

|

|

|

polychromator |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

diffraction grating |

|

transfer |

plasma |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

optics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

observation zone |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R.F. coil |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

generator |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

photomultipliers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

behind exit slits |

|

auxiliary gas |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

outer (plasma |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

coolant) gas |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aerosol (+ injector gas) |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

interface |

|

|

|

|

argon |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

(analog |

|

|

digital) |

|

nebulizer |

|

|

injector gas |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

drain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

peristaltic pump |

||||||

|

|

|

computer |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

with associated software |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

solution |

|

auto sampler |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VDU |

|

|

|

|

teletype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

Figure 24 inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP–AES) |

Schematic diagram of an |

|||||||||||||||

inductively coupled plasma-atomic (ICP) system. Source: M. Thompson, and J.N. Walsh: A handbook of inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (London: Blackie, 1983), fig. 1.2.

this is used as an ion source for a quadrupole mass spectrometer. Thus, instead of measuring the atomic emission from the sample, the mass spectrum is recorded. The concentrations of elements are therefore determined by measurement of their individual isotopes after calibrating with standard solutions of known concentrations. Detection limits are uniformly lower than ICP-AES or flame AAS

(ATOMIC ABSORPTION SPECTROPHOTOMETRY).

The technique is also capable of determining isotope ratios. However, currently, the precision of these does not match the method of thermal ionisation mass spectrometry conventionally used, for example, for lead isotope ratios.

K.E. Jarvis et al.: Handbook of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Glasgow, 1992).

MC

inductive statistical explanation see

INDUCTIVE AND DEDUCTIVE EXPLANATION

Indus civilization The earliest urban society of South Asia, the Indus (or Harappan) civil-

ization emerged out of the local traditions of the early 3rd millennium BC focused on several small regional centres (e.g. AMRI and HARAPPA). It

may |

be divided into three basic |

phases: |

Early |

Harappan (c.4000–2600 BC), |

Mature |

Harappan (c.2600–1900 BC) and Late Harappan (c.1900–1300 BC). The excavated remains at a number of Indus sites provide evidence of a complex and varied subsistence economy involving a wide range of methods of irrigation. Plant domesticates included wheat, barley, millets, pulses, vegetables and, in some areas, rice. Domesticated animals included cattle, water-buffalo, sheep and goat; wild animals and fish were also consumed (Meadow 1989; Weber 1991).

More than a thousand Indus-civilization sites have been found across a range of environmental zones in Pakistan, Afghanistan and northern India. The Indus period was characterized by the development of a complex 4- or 5-level hierarchy of settlements, concentrating on several major urban centres such as MOHENJO-DARO and Harappa. Other first-level cities were GANWERIWALA,

304 INDUS CIVILIZATION

Rakhigari (80 ha in area) and possibly Dholavira; second-level towns of 10–50 ha include KALIBANGAN and Judeirjo Daro; and third-level towns in the 5–10 ha range include AMRI, LOTHAL AND CHANU-DARO. The smallest level of town, at 1–5 ha, comprised such settlements as KOT DIJI,

Balakot, SUTKAGEN DOR and NAUSHARO. There

were also many smaller sites, such as pastoral camps and specialized craft-production locales.

There has been much debate regarding the social and political organization of the Indus civilization; excavated remains at Mohenjo-Daro and other sites reveal complex urban plans, monumental constructions and a highly developed economic structure (Shaffer 1982; Malik 1984; Kenoyer 1991: 366–9). Indus sites, however, are still lacking in many of the traits characteristic of other early civilizations, such as warfare, royal burials and unambiguously identified palaces and temples. This may partly be a function of the poor quality of many of the early excavations conducted in the 1920s–1940s, which still provide most of the data on the Indus civilization. However, the situation may also reflect the fact that the archaeological models commonly applied to early states are perhaps unable to account for the full range of variability in ancient civilizations. For example, Kenoyer has suggested that Indus political structure may have been structured around several groups of semi-autonomous elites (1991:369), with an over-arching coherence in material culture and possibly ideology (Possehl 1991: 273–4), rather than being characterized by a well-integrated bureaucratic and administrative structure familiar to scholars of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

During the Early Indus period (c.4000–2600 BC), the Indus Valley and surrounding highlands were characterized by the emergence of a number of localized regional traditions (e.g. AMRI, Nal, KOT DIJI, Kili Ghul Muhammad, Hakra). This was a period in which many of the traits that would characterize the succeeding urban period appeared, including specialized craft production, longdistance trade, intensification of agriculture and stock rearing, as well as the emergence of status differentiation and the development of large central settlements with monumental architecture.

The Mature Indus period emerged from this complex of localized traditions, but there is some disagreement as to whether this transition was sudden and dramatic (e.g. Possehl 1991) or the result of more gradual continuous transformations (Mughal 1990; Kenoyer 1991). The urban phase of the Indus civilization ended in c.2100–1900 BC: in some areas sites were abandoned completely, while

in others, such as Harappa, occupation continued at a much smaller scale.

A variety of factors appear to have contributed to the decline of the Indus civilization, possibly including changing cultural and historical factors such as the overextension of economic and ritual networks (Kenoyer 1991; 370), as well as environmental changes that would have affected agricultural potential, such as the movement of the Indus river-course to the east and the drying up of the densely settled Ghaggar-Hakra region, where GANWERIWALA was located (Misra 1984). No evidence exists for extensive destruction or conflict at the end of the Indus period; instead there appear to have been localized patterns of depopulation or migration, and a return to more localized archaeological traditions.

I. Mahadevan: The Indus script: texts, concordance and tables (Delhi, 1977); G.L. Possehl, ed.: Ancient cities of the Indus (New Delhi, 1979); S. Ratnagar: Encounters: the westerly trade of the Harappa Civilization (Delhi, 1981); G.L. Possehl: Harappan civilization (New Delhi, 1982); J. Shaffer: ‘Harappan culture: a reconsideration’, Harappan Civilization, ed. by G.L. Possehl (Delhi, 1982), 41–50; S.C. Malik: ‘Harappan social and political life’, Frontiers of the Indus Civilization, ed. B.B. Lal and S.P. Gupta (Delhi, 1984), 201–10; V.N. Misra: ‘Climate, a factor in the rise and fall of the Indus Civilization’, Frontiers of the Indus Civilization, ed. by B.B. Lal and S.P. Gupta (Delhi, 1984), 461–90; R.H. Meadow: ‘Continuity and change in the agriculture of the Greater Indus Valley: the palaeoethnobotanical and zooarchaeological evidence’, Old problems and new perspectives in the archaeology of South Asia, ed. by J.M. Kenoyer (Madison, 1989), 61–74; D.K. Chakrabarti: The external trade of the Indus Civilization

(Delhi 1990); M.R. Mughal: ‘Further evidence of the Early Harappan culture in the Greater Indus Valley’, South Asian Studies 6 (1990), 175–200; J.M. Kenoyer: ‘The Indus Valley tradition of Pakistan and Western India’, JWP 5 (1991), 331–85; G.L. Possehl: ‘Revolution in the urban revolution: The emergence of Indus Civilization’, Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1991), 261–82; S.A. Weber: Plants and Harappan subsistence

(New Delhi, 1991); W.A. Fairservis: The Harappan civilization and its writings (New Delhi, 1992).

CS

industrial archaeology Subdiscipline that developed in archaeology during the mid-20th century to investigate the tangible evidence of the social, economic and technological development of the industrial era. The period covered extends from the early 18th century to the first decades of the 20th, although some would include all of the 20th century. Industrial archaeology has also been defined as a thematic discipline dealing with the methods by which humankind have achieved their