A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfKhirbet Kerak (Beth Yerah) One of the largest tell-sites in the Levant, situated immediately to the southwest of Lake Tiberias, 35 km east of Haifa. It was excavated between 1944 and 1964, revealing 23 strata dating from the end of the Chalcolithic period (c.3200 BC) to the 5th century AD, when it became the site of a Byzantine church. Khirbet Kerak gave its name to an important Early Bronze Age culture of the 3rd millennium BC in Syria-Palestine which appears to have been a Levantine version of

the EARLY TRANSCAUCASIAN CULTURE in

Anatolia. The Khirbet Kerak culture, roughly contemporary with the Early Dynastic phase in SUMER, is particularly characterized by red and red-and- black burnished pottery often decorated with geometrical motifs. Extensive traces of Khirbet Kerak ware have survived at other sites in the Levant, including JERICHO, BETH SHAN, Tell Judeida and UGARIT.

R.B.K. Amiran: ‘Connections between Anatolia and Palestine in the Early Bronze Age’, IEJ 2 (1952), 89–103; B. Maisler, M. Stekelis and M. Avi-Jonah: ‘The excavations at Beth Yerah (Khirbet el-Kerak)’, IEJ 2 (1952), 165–73, 218–29.

IS

Khmer see ANGKOR; BAN TAMYAE; KOH KER; LOPBURI; PHIMAI

Khoisan see AFRICA 4

Khok Charoen Cemetery of 44 extended inhumation buria ls, located in the Pa Sak valley, a tributary of the Chao Phraya River in central Thailand. When excavated by Watson and LoofsWissowa in 1966–7, the site yielded grave-goods such as pottery vessels, marine shell jewellery and stone adzeheads; no copper-based artefacts were found. The considerable variation in the quantity of goods deposited with individual burials may indicate some ranking, or at least differential personal achievement. Two thermoluminescence dates of 1180 and 1080 BC have been derived from the mortuary pottery, but when compared to the pottery typology these seem too late by 500–1000 years.

W. Watson: ‘Khok Charoen and the early metal age of Central Thailand’, Early South East Asia, ed. R.B. Smith and W. Watson (Oxford 1979), 53–62.

CH

Khok Phanom Di Large settlement (5 ha) and cemetery site dated to c.2000–1500 BC, located on a former shoreline now about 24 km from the Gulf of

KHORMUSAN 335

Siam in Thailand. After several small excavations, a major research programme took place in 1985 under the direction of Charles Higham and Rachanie Thosarat Bannanurag. This included excavation, flotation of a sample of all contexts and coring for sediment and pollen analysis. It was found that the site had been occupied between 2000 and 1500 BC. The excavations of 1985 encountered a sequence which began with industrial and occupation remains, then involved a cemetery, and finally reverted to a pottery-making area.

A remarkable feature of the cemetery was the pace with which the deposits accumulated. Within four centuries, the mound rose by 6 m. The cemetery pattern reveals that groups of individuals were laid out in clusters on a chequer-board pattern; as time went by, the dead were eventually buried above their ancestors. Two such groups have been traced through about 20 generations.

C.F.W. Higham et al.: ‘Human biology, environment and ritual at Khok Phanom Di’, WA 24/1 (1992), 35–54; C.F.W. Higham and R. Bannanurag: The excavation of Khok Phanom Di, a prehistoric site in central Thailand I: The excavation, chronology and human burials (London, 1990).

CH

Khok Phlap Cemetery site located west of the Chao Phraya River in central Thailand. The site was formerly located on or near the coast. Excavations there by Sod Daeng-iet encountered a cemetery in which people were inhumed in association with pottery vessels, shellfish remains and stone, bronze and turtleshell jewellery. Although not scientifically dated, the typology of the artefacts suggest that the site belongs to the 1st century BC.

S. Daeng-iet: ‘Khok Phlap: a newly discovered prehistoric site’, Muang Boran 4/4 (1978) 17–26.

CH

Khor Musa see KHORMUSAN

Khormusan Final Lower Nubian and Upper Egyptian lithic tradition of the Middle Palaeolithic period, named after Khor Musa (near Wadi Halfa in the northern Sudan) where the first Khormusan assemblage was identified at site 1017. Dating from about 45,000 to 15,000 BC, it is roughly contemporary with the Dabban industry (see HAUA FTEAH). The typical Khormusan site comprises an area of debris close to the Nile, covering several thousand square metres and consisting of numerous clusters of artefacts around hearths (i.e. small encampments rather than continuous stretches of

336 KHORMUSAN

settlement). The toolkit virtually always consists of LEVALLOIS flakes and cores, burins and denticulates, with a wide diversity of tool-sizes, while the surviving organic remains suggest that foodsources ranged from catfish to wild cattle, gazelles, antelopes and hippopotami.

A.E. Marks: ‘The Khormusan: an Upper Pleistocene industry in Sudanese Nubia’, The Prehistory of Nubia I, ed. F. Wendorf (Dallas, 1968), 315–91; M.A. Hoffman: Egypt before the pharaohs (New York, 1979), 70–7.

IS

Khorsabad (anc. Dur-Sharrukin) Tell-site of one of the most important cities of the Assyrian empire, located in northern Iraq, 24 km northeast of Mosul. It was a new capital founded by Sargon II (c.721–705 BC) on a virgin site, apparently built in less than ten years. But its duration as capital was even briefer than that of its Egyptian counterpart, the city of Akhetaten at EL-AMARNA; in 704 BC Sargon’s city was abandoned in favour of NINEVEH by his successor Sennacherib after Sargon had been killed in battle. Unlike el-Amarna, however, the settlement continued to be occupied for almost a century after it had fallen out of royal favour, until its destruction at the end of the Assyrian empire in 612 BC. The principal elements of the main citadel at Dur-Sharrukin, constructed on a terrace about 16 m in height at the northern corner of the city, were a seven-stage ziggurat with each storey originally painted a different colour, the palace of Sargon (decorated with frescoes, painted reliefs and glazed bricks), the palace of his brother Sinahusur, and the temple of Nabu (linked to the main palace by a stone viaduct). ‘Palace F’, in the southwestern corner of the city, incorporates a form of HILANI (a type of pillared building), perhaps deliberately borrowing from Aramaean architecture in Syria; it was used as an arsenal for storage of weapons and booty, as at Nineveh and NIMRUD.

The site was excavated in 1843–4 by Paul-Emile Botta, who transported some of the LAMASSU (colossal statues of winged bulls) from the palace gateways to Paris, where they were the first substantial Mesopotamian sculptures to be displayed in a European museum. Unfortunately many other statuary and reliefs from Khorsabad were lost in the Tigris while in transit for France. The site was also excavated by Victor Place in 1851–5, and in 1930–5 Gordon Loud discovered a new king-list (Poebel 1942) and uncovered large areas of temples and houses which had escaped Botta’s notice.

P.E. Botta and E. Flandin: Les monuments de Ninive, 5 vols (Paris, 1849–50); M. Pillet: Khorsabad: les découvertes de Victor Place en Assyrie (Paris, 1918); G. Loud, H.

Frankfort, T. Jacobsen and C.B. Altmann: Khorsabad, 2 vols (Chicago, 1936–8); A. Poebel: ‘The Assyrian king list from Khorsabad’, JNES 1 (1942), 247–306; T.A. Busink: ‘La Zikkurat de Dur-Sarukin’, Comptes rendus de la troisième rencontre Assyriologique internationale (Leiden, 1954), 105–22; H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth, 1970), 143–54, 170–4, Figs 196–9.

IS

Kiet Siel see ANASAZI

Kiik-Koba Oldest Palaeolithic cave-site in the Crimea (Ukraine), situated in the valley of the river Zuya, 25 km east of Simferopol. The sequence, discovered and excavated in the 1930s by G.A. Bonch-Osmolovsky, included two MOUSTERIAN occupation levels. the upper level included an artificial enclosure made of large cobbles, and two burials of NEANDERTHALS – one adult and one child (5–8 months old). The bodies had been laid close to each other in contracted postures.

G.A. Bonch-Osmolovsky: ‘Itogi izhucˇcenija krymskogo paleolita’ [Results of studies of the Crimean Palaeolithic],

Transactions of the INQUA Conference, vol. vi (Moscow, 1934), 114–83.

PD

Kili Ghul Muhammad see QUETTA

Kilwa see SWAHILI HARBOUR TOWNS

Kinsei Late/Final Jomon settlement in Yamanashi prefecture, Japan (c.2500–300 BC). Thirty-five buildings including a row of Final Jomon stone-paved houses were associated with a series of adjoining circular and rectangular stone burial cists interspersed with phallic standing stones and ritual deposits of juvenile wild boar and religious artefacts.

T. Niitsu and Y. Yamaki: Kinsei iseki II [The Kinsei site II] (Kofu, 1989).

SK

Kintampo Village in Central Ghana which has given its name to the ‘Kintampo culture’, first identified by Oliver Davies. The culture is known from both open-air and rockshelter sites, as at Ntereso and Kintampo respectively, and it is characterized by the following elements: stone rasps (described by Davies as ‘terracotta cigars’), polished stone axes and arm rings, grooved abrading stones and grinding stones, comb-stamped pottery, and

burnt daub with wooden pole and/or thatch impressions. Kintampo 6 rockshelter, excavated by Colin Flight in 1967–8 (60 sq. m) and by Ann B. Stahl in 1982 (3 sq. m), has provided a particularly important stratigraphic sequence, in which the Kintampo culture was preceded by a so-called ‘Punpun phase’. Flight emphasized the distinction between the two. In his view, the Kintampo culture alone was characterized by a food producing economy, and he regarded it as intrusive to the area. By contrast, Stahl points out that in the portion of the site excavated by her there was a stratigraphic overlap between Punpun and Kintampo pottery, and she also believes that there was no decisive economic break between the two cultures. The Kintampo culture alone had domestic goats and/or sheep, but in Stahl’s view the bones earlier identified as domestic cattle may have belonged to forest buffalo. Elaeis guineensis, Canarium schweinfurthii, and Celtis sp. occur throughout the sequence, as do legume-like seeds earlier identified by Flight as cultivated cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata).

Stahl therefore proposes an alternative model for the origins of food production in the area and the Kintampo culture, whereby an indigenous Late Stone Age population interacted with an incoming one to produce a distinctive local adaptation based on a fusion of autochthonous and exotic traits. There was a progressive introduction of diagnostically Kintampo elements, and the development of a ‘garden hunting’ economy. A set of 18 radiocarbon dates from six sites with Kintampo and/or Punpun occupations span the period from 3700 to 2770 BP.

C. Flight: ‘The Kintampo culture and its place in the economic prehistory of West Africa’, Origins of African plant domestication, ed. J.R. Harlan et al. (The Hague/Paris, 1976), 211–21; A.B. Stahl: ‘Reinvestigation of Kintampo 6 rock shelter, Ghana: implications for the nature of culture change’, AAR 3 (1985), 117–50.

PA-J

Kisalian see AFRICA 5

Kish (Tell el-Uhaimir, Tell Ingharra, Tell elKhazna and Tell el-Bender) One of the most important SUMERIAN cities, surviving in the form of a group of mounds covering an area of some four square kilometres in southern Iraq, about 20 km to the east of BABYLON. The rulers appear to have exercised some kind of hegemony over the other towns of the Early Dynastic period (c.2900–2350 BC); according to the Sumerian King List, the kingship was lowered down from heaven to Kish after

KITCHEN MIDDEN, SHELL MIDDEN 337

the Flood. First identified in 1873, the site was excavated by Henri de Genouillac in 1912 and by an Anglo-American expedition between 1923 and 1933. There are strata dating to the UBAID and URUK periods, but the main occupation dates to the

and Early Dynastic periods

(c.3200–2350 BC).

The site includes one of the earliest known Mesopotamian ‘palaces’ (Moorey 1964) as well as a number of cemeteries of the Early Dynastic period. Cemetery Y includes several ‘cart burials’, which were at first identified as the ‘chariot burials’ of Sumerian ‘princes’ (Langdon and Watelin 1934). There are probably seven such graves, each originally containing several human bodies in association with a large wheeled vehicle drawn by a bovid. The dating and significance of the cemetery are both subjects of some debate, but the latest evidence suggests that they are the burials of non-royal individuals of the ED II phase (Moorey 1978). There are also substantial neo-Babylonian and Sasanian remains.

S. Langdon and C. Watelin: Excavations at Kish, 3 vols (Paris, 1924–34); P.R.S. Moorey: ‘The “plano-convex building” at Kish and early Mesopotamian palaces’, Iraq 26 (1964), 83–98; McG. Gibson: City and area of Kish

(Miami, 1972); ––––: The Oxford–Chicago excavations at Kish (1923–33) (Oxford, 1978).

IS

kitchen midden, shell midden Term used in a general sense to describe an archaeological deposit formed largely of refuse from food preparation and, in a more particular sense, to describe large mounds of shells (with associated cultural debris) found at some coastal sites. Examples of the latter include the ASTURIAN complex in northern Spain and the ERTEBØLLE culture in Denmark and Scandinavia. Another group is located at the mouth of the Tagus in Portugal. While shell middens are a particular feature of Mesolithic Atlantic economies, they also exist in the Mediterranean – for example, Île de Riou in the bay of Marseilles has impressive limpet middens perhaps dating from 6000–5000 BC. The site is associated with very early Neolithic pottery and querns, which suggests that shellfish remained part of some local economies even after elements of farming systems were adopted.

Recent studies of shell middens have tended to stress that although they often form the most impressive physical evidence of a huntinggathering economy, in overall nutritional terms they may only form a minor or seasonal part of a much more complicated foraging strategy. Even where marine resources underpinned a

338 KITCHEN MIDDEN, SHELL MIDDEN

hunter-gatherer economy, sea-bird catching, eggcollecting and fishing may have been more important components in terms of their nutritional value. At the same time, at some sites shellfish may have represented a crucial ‘stand-by’ resource at times of the year when other resources were very

limited (see also FORAGING THEORY and NAMU).

C. Bonsall, ed.: The Mesolithic in Europe (Edinburgh, 1985).

RJA

kiva Type of ceremonial structure found at PUEBLO sites in the southwestern region of North America, c.AD 1–1540. Kivas are usually at least partly subterranean and shapes vary, with curvilinear forms (e.g. circular, D-shaped and keyhole-shaped) being particularly characteristic of ANASAZI settlements (e.g. PUEBLO BONITO). The largest kivas (known as ‘great kivas’) probably served as the ceremonial centres for whole communities; these can be up to 10 m in diameter.

IS

Kivik The reconstructed rectangular chamber under this round tumulus of the late 2nd millennium BC, located in Skåne in Sweden, is lined with a unique corpus of Bronze Age decorated slabs. The slabs present a series of scenes and motifs (boats, axes, spoked wheels) related to contemporary rock art, but more carefully arranged into horizontal zones. The most striking scenes show a charioteer – the earliest depiction of such in northern European art – moving behind four warriors, and a scene in which eight robed figures stand on either side of what may be an altar. The engravings may relate to the funerary rites of the entombed. The tomb was in a poor condition before its investigation, and the small amount of associated material does not allow for a precise dating.

C.-A. Moberg: Kiviksgraven (Stockholm, 1975); K. Barup et al.: Kivik (1977); N. Sandars: Prehistoric art in Europe

(London, 1985; 1st edn 1968), 286–8.

RJA

Klasies River Mouth Caves A number of caves and rockshelters with evidence of prehistoric occupation, situated along a short stretch of coast, close to the mouth of the Klasies River, 84 km west of Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Five of these form a cluster referred to as the main site. Cave 1 is a seacut cave at about 6–8 m above sea level. Cave 2 is situated in the cliff above, at 18–20 m above sea level and was made accessible by a huge accumula-

tion of deposits to the right of Cave 1, including human occupational debris, against the cliff, in what is referred to as Shelter 1A. Cave 1C is a small cavern devoid of human occupation, to the right of Cave 1, and buried by the deposits of Shelter 1A. Shelter 1B lies to the left of Cave 1, separated by a spur of rock.

The sites were first excavated by Singer and Wymer in 1967 and 1968, and subsequently in 1984–6 by H.J. Deacon, for the purpose of recovering environmental data and samples for a range of dating techniques. The combined main site sediments (16 m) contain a long sequence of MSA (Middle Stone Age) occupations designated MSA I, MSA II, HOWIESON’S POORT, and MSA III, which has become the standard reference for the MSA in the southern part of South Africa. On a combination of dating techniques and environmental data the MSA I material dates to before 110,000 uncal BP and MSA II material to c.90,000–c.70,000 uncal BP. Howieson’s Poort is less clearly dated to a span of several thousand years

around 70,000 uncal BP. ANATOMICALLY MODERN

HUMAN remains are associated with MSA I and MSA II in cave 1, shelter 1A, and shelter 1B.

R. Singer and J. Wymer: The Middle Stone Age at Klasies River Mouth in South Africa (Chicago, 1982); H.J. Deacon: ‘Late Pleistocene palaeoecology and archaeology in the southern Cape, South Africa’, The human revolution, ed. P. Mellars and C. Stringer (Edinburgh, 1989), 547–64.

RI

Kleinaspergle (Klein Aspergle, Kleiner Asperg) Massive rounded tumulus (8 m high and 60 m in diameter) covering the richest of the Iron Age ‘princely graves’ that lie at the foot of the hillfort of Hohenasperg in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Unlike most of the princely tumuli associated with major hillforts, Kleinaspergle is dated to the La Tène A period, rather than the earlier Hallstatt D period. (The settlement at Hohenasperg has never been properly excavated because it is overlain by a medieval castle, but was presumably still in use at the time of the Kleinaspergle interment.) When the tomb was partially excavated in 1879 the main chamber was found to have been robbed in antiquity, but a secondary chamber contained a series of exotic imports and artefacts of Celtic manufacture in a fully developed ‘Early La Tène’ style (see LA TÈNE). The imports, an Etruscan stamnos and Attic red-figure ware with locally added gold mounts, securely date the tomb to the second half of the 5th century BC (perhaps 430/20 BC). The Celtic items reveal the influence

of the Mediterranean world, and include a flagon in the Etruscan-influenced high-shouldered beaked form – paralleled in the classic flagons from BasseYutz – as well a series of gold mountings and a plaque; two drinking horn ends strongly suggest Scythian influence.

W. Kimmig: ‘Klein Aspergle’, Trésors des princes Celtes, eds. J.P. Mohen et al., exh. cat. (Paris, 1987), 255–64;

––––: Das Kleinaspergle (Stuttgart, 1988).

RJA

k-means see CLUSTER ANALYSIS

Knossos Foremost palace complex of the MINOAN culture of Crete, excavated by Arthur Evans in (principally) 1921–35. The material from Knossos allowed Evans to divide the Minoan chronology into three main phases: Early, Middle and Late. The site was first occupied during the Neolithic period, from the 7th millennium BC onwards. After a little-understood formative Early Minoan period, a substantial palace was built around 2000 BC; this was surrounded by a town but excavations of this and later phases have concentrated on the palace and only a few Knossos townhouses have been excavated. This first palace seems to have been destroyed by an earthquake in around 1700 BC. The grandest palace was then constructed, and continued in use until the 14th century BC – significantly after the massive volcanic explosion on the island of Santorini once thought to have precipitated Knossos’s destruction (see THERA). It seems clear that from 1700 BC, at least, Knossos was the pre-eminent settlement on Crete, but the nature of its relations with other palace sites is still debated. In the final years before its destruction Knossos may have been controlled by princes of the MYCENAEAN civilization that had arisen on the Greek mainland.

The palace consists of a central court surrounded by suites of ceremonial rooms and storage and work rooms. The complex was built on two (or even three) storeys; the upper floors were of mudbrick laced with timber, possibly to strengthen them against tremors and earthquakes. The design displays sophisticated architectural features such as light wells, stone-lined drainage channels and clay piping, dressed stone colonnades and plastered interior walls. The rooms included storage magazines, royal reception rooms and shrines. Certain rooms are decorated with elaborate wallpaintings, the surviving examples of which mostly date from about 1550 BC onwards. Knossos and Thera provide the principal examples of Minoan

KODIAK TRADITION 339

painting. Themes include formal processions and religious festivals, athletes somersaulting over bulls, dancing girls, pictures of animals (monkeys, cats, deer) within landscapes, marine scenes (flying fish etc) and decorative schemes based around banding and floral motifs. The style is flexible, naturalistic and full of life; later examples are more monumental and rigid and betray Mycenaean influence.

A.J. Evans: Palace of Minos at Knossos (London, 1921–36); M. Ventris and J. Chadwick: Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Cambridge, 1973); G. Cadogan: Palaces of Minoan Crete (London, 1976); M.S.F. Hood and D. Smyth:

Archaeological survey of the Knossos area (London, 1981); J.W. Graham: The palaces of Crete (Princeton, 1987); R. Hägg and N. Marinatos: The function of the Minoan palaces

(Stockholm, 1987); P. Halstead: ‘On redistribution and the origin of the Minoan-Mycenaean palatial economies’

Problems in Greek prehistory, ed. E.B. Frence and K.A. Wardle (Bristol, 1988), 519–30; J.W. Myers et al.: The aerial atlas of ancient Crete (London, 1992).

RJA

Knowth One of three giant Neolithic PASSAGE GRAVES in the famous group, Knowth was excavated from 1960 by George Eogan and probably dates from the end of the 4th millennium BC. The conical mound has an oval groundplan (80 × 90 m) and covers two opposed megalithic passage-graves: Knowth East (40 m long with an elaborate cruciform and corbelled chamber) and West (24 m long). Like nearby NEWGRANGE, the external perimeter of the mound was lined with kerbstones (127). Knowth also produced one of the finest examples of Neolithic decorative art: a flint macehead delicately carved with spirals and faceted lozenges.

G. Eogan: Knowth and the passage-tombs of Ireland

(London, 1986)

RJA

Kobadi see AFRICA 2

Kobystan see CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES

Kodiak tradition Tradition known from the Pacific Eskimo region around Kodiak Island in southwestern Alaska, where it replaced the Ocean Bay tradition around 2500 BC. It is characterized by a wide variety of polished slate implements. The period from 1500 BC to AD 1000 is known as the Kachemak stage of the Kodiak tradition, and is distinguished by an increasingly elaborate material culture. The introduction of aspects of

340 KODIAK TRADITION

THULE culture from northern Alaska by AD 1000 marked the end of the Kodiak tradition.

D.E. Dumond: The Eskimos and Aleuts (London, 1987).

RP

Kofun period (AD 300–710) |

see JAPAN 4 |

Koh Ker Court centre of |

Jayavarman IV |

(AD 928–942), located 80 km northeast of ANGKOR. Founded as a rival to Angkor, then under the control of Harsavarman I and Isanavarman II, Jayavarman IV was responsible for the construction of Prasat Thom, one of the largest temple mausolea known from the Angkorean period. It was associated with a large reservoir and a range of secular buildings, which matches the usual configuration of a cult centre of this period. The art style, particularly on the stone lintels, represents a number of innovations giving rise to the so-called Koh-Ker style.

L.P. Briggs: ‘The ancient Khmer empire’, TAPS 4/1 (1951), 1–295.

CH

Kojiki One of the two earliest surviving chronicles of Japan, compiled under the Ritsuryo state as part of the legitimization of the ruling dynasty (the other being the Nihon Shoki). The Kojiki was compiled in AD 712 and consists primarily of a brief mythology and genealogical lists. Both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki were based on earlier, non-extant texts, the Teiki and Kyuji, and supplemented by four later works (together with which they comprised the Six Ancient Histories). They provide important documentary evidence for the Kofun period (see JAPAN 4).

D.L. Philippi, trans.: Kojiki (Tokyo and Princeton, 1968).

SK

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test see GOODNESS-

OF-FIT

Kolomiishchina (Kolomiiscina) see

TRIPOLYE

Kolomoki North American site, covering some 150 ha in the Chattahoochee River valley of southwestern Georgia, at which the primary occupation is characteristic of the Weeden Island culture (found along the Gulf Coastal Plain in the Late WOODLAND period). Kolomoki consists of a large, rectangular PLATFORM-MOUND (Mound A) at the

east end of a plaza, an arc-shaped village surrounding the plaza, and a number of smaller mounds located both inside and outside the village. Mound A measures 60 × 100 m at the base and is 17 m high. Several of the smaller mounds contained evidence of elaborate mortuary events involving the burial of high status individuals. The village occupation and most mound construction date to between AD 300 and 500.

W. Sears: Excavations at Kolomoki: final report (Athens, GA, 1956); J. Bense: Archaeology of the Southeastern United States: Paleoindian to World War I (New York, 1994), 170–5.

RJE

Kolo rock paintings The most important collection of hunter-gatherer art in eastern Africa, located in the Kondoa district of north-central Tanzania. While the finest concentration is on a series of rock-shelters around Kolo (on the escarpment overlooking the Maasai Steppe), their distribution is much broader, extending from Kondoa into districts to west and northwest. Most of the painted rock-shelters were occupied on several occasions, and some of them possess deep sequences of Late Stone Age deposits spread over several millennia. Rarely however is it possible to correlate individual layers with particular paintings, therefore archaeologists’ aspirations of employing the evidence of the paintings, alongside the excavated bones and lithics, to illustrate the succession of cultures and economies of Late Stone Age hunter-gatherers have been frustrated except in a general way. Attempts have been made to reconstruct a sequence of painting styles, especially by noting superpositions; but the results seem to be of limited validity.

H.A. Fosbrooke, L.S.B. Leakey et al.: Tanganyika Notes and Records 29 (1950), 1–61; M.D. Leakey: Africa’s vanishing art (London, 1983).

JS

kom see TELL

Kom el-Ahmar see HIERAKONPOLIS

Kom Medinet Ghurob |

see GUROB |

Kom Ombo (anc. Ombos) |

Egyptian stone-built |

temple and settlement site located 40 km north of Aswan, with surviving structural remains dating from at least as early as the 18th dynasty (c.1550–1070 BC). There are also a number of

Upper Palaeolithic sites scattered over the surrounding region (see SEBILIAN). The Ptolemaic and Roman temple, cleared by Jacques de Morgan in 1893, is an unusual structure divided into two halves, with one dedicated to the crocodile-god Sobek and the other to the hawk-god Haroeris.

J. de Morgan et al.: Kom Ombos, 2 vols (Vienna, 1909).

IS

Kom el-Shuqafa see ALEXANDRIA

Kondoa see KOLO ROCK PAINTINGS

Koobi Fora see EAST TURKANA

Koptos (Qift, anc. Kebet) Egyptian site located on the east bank of the Nile about 40 km north of Luxor. The surviving settlement remains at Koptos date back to the beginning of the historical period (c.3000 BC), including three colossal limestone statues of the local fertility god Min and various other items of ‘preformal’ sculpture, which were excavated by Flinders Petrie in an Early Dynastic context at the temple of Min. The upstanding remains of the temple date mainly to the New Kingdom and later (for a description of preformal art at Koptos and other Early Dynastic Egyptian sites see Kemp 1989: 64–91). To the east of the main city site there are cemeteries dating to the late predynastic period (c.3300–3000 BC), when NAQADA, situated almost opposite Koptos on the west bank, was the dominant town in the region. The Greek and Roman remains at Koptos have been studied by Claude Traunecker and Laure Pantalacci (1989).

W.M.F. Petrie: Koptos (London, 1896). A.J. Reinach:

Rapports sur les fouilles de Koptos (Paris, 1910); B.J. Kemp: Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization (London, 1989); C. Traunecker and L. Pantalacci: ‘Le temple d’Isi à El Qual’a près de Coptos’, Akten München 1985 3, ed.: S. Schoske (Hamburg, 1989), 201–10.

IS

Korolevo Stratified Palaeolithic site, situated on the high terrace of the Tisza river, in the Transcarpathian region of the Western Ukraine near the Hungarian border. The site was discovered in 1974 by V.N. Gladilin and comprises 14 levels, including seven ACHEULEAN and six MOUSTERIAN strata; the upper stratum allegedly belongs to an early stage of the Upper Palaeolithic. The archaeological deposits range in date from the Günz-Mindel interglacial to the Early Würm. The five Acheulean levels at Korolevo show consider-

KOSTENKI-BORSHEVO 341

able cultural continuity, and seem quite different to the other Acheulean assemblages of central and western Europe: choppers are common, handaxes are atypical, and there is an early development of the

LEVALLOIS TECHNIQUE.

V.N. Gladilin: Problemy rannego paleolita vostocˇnoi Evropy

[The problems of the early Palaeolithic in Eastern Europe] (Kiev 1976).

PD

Körös culture see STARCEVO (STARCEVO- |

|

ˇ |

ˇ |

KÖRÖS-CRIS¸ ) CULTURE

Kostenki-Borshevo Group of Upper Palaeolithic open-air sites situated in the valley of the River Don, 40 km south of the town of Voronezh, in central Russia. Discovered by I.S. Polyakov in 1879, the sites have been excavated since the 1920s by P.P. Efimenko, and later by N.D. Praslov and others. There are 24 sites in the group, 10 of which are multi-layered. At the oldest sites, two distinct cultural traditions are recognizable: the Streletzkian and Spitzinian. The Streletskian, characterized by archaic MOUSTERIAN-like tools, side-scrapers and laurel-leaf points, is represented at sites such as Kostenki 1, stratum 5; Kostenki 6, stratum 5; Kostenki 12, stratum 3. In the latter case, charcoal from stratum 1a (i.e. the layer considerably above the Streletskian level) has been radiocarbon dated to 34700 ± 700 BP (GrN 7758). The fauna included horse, mammoth, reindeer, wolf, red deer, rhinoceros and polar fox.

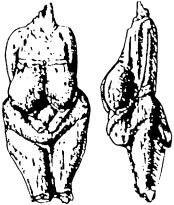

Figure 27 Kostenki-Borshevo Upper Palaeolithic ‘Venus figurine’ from Kostenki-Borshevo, central Russia. Source: A. Velichko (ed.): Arheolojia i paleogeografija pozdnego paleolita russkoi rauniny

(Moscow: Nauka, 1981).

342 KOSTENKI-BORSHEVO

The lithic inventory of the Spitzinian lacks any archaic elements and is characterized by a high proportion of end-scrapers, a variety of burins, and scaled pieces. It has been investigated at two sites: Kostenki 12 (stratum 2) and Kostenki 17 (stratum 2). The latter site was radiocarbon dated to 32000 +2000/–1600 BP (GrN-10512). The faunal remains consist of wolf, horse, bison, reindeer, mammoth, polar fox, hare and antelope-saiga.

A later industry known as the ‘Gorodtsovian’ is also present at the sites (eg Kostenki 14, stratum 2). It presents a developed Upper Palaeolithic technology with a variety of small end-scrapers, scaled pieces, knives and a peculiar bone industry which includes spatulae. Radiocarbon dating at Kostenki produced several dates; the oldest are 32700 ± 700 BP (GrN-7758) and 25100±150 BP (LE-1437). The fauna includes horse, hare, red deer, rhinoceros, reindeer, mammoth, wolf, antelope-saiga, bison and polar fox. Another distinct industry, of uncertain age but with characteristic points, end-scrapers and scaled pieces (Telmanian), has been identified in the upper stratum of Kostenki 8. The fauna consists of wolf, hare, mammoth, horse, polar fox, cave lion and bison. A sample of charcoal from the underlying stratum 2 has been radiocarbon dated to 27700 ±750 BP (GrN-10509).

A fully developed Upper Palaeolithic tradition (Kostenkian) is represented at the site of Kostenki 1, stratum 1. A series of radiocarbon measurements range from 24100±500 to 21300±400 BP. The fauna consists of mammoth (more than 100 individuals), wolf, hare, polar fox, fox, horse, reindeer, brown bear and musk ox. The lithic inventory includes burins (the most common type), end-scrapers and a characteristic type of shouldered point (the ‘Kostenki-type’). Stratum 1 of Kostenki 1 contained over 150 specimen of ‘mobiliary art’: anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines. The female figurines made of mammoth ivory and marl are the most common type. Amongst the zoomorphic types, mammoths, lionesses and brown bears may be recognized; see also GRAVETTIAN and

‘VENUS’ FIGURINES.

One of the most outstanding achievements of Soviet archaeology in the 1930s was the discovery of structures consisting of mammoth bones – usually interpreted as dwellings. Two such structures were located in stratum 1 of Kostenki 1. They are oval-shaped (36 by 14–15 m), oriented southeast to northwest, and have a row of hearths along one of the axes. The structures are surrounded by 10–12 storage pits.

N.D. Praslov and A.N. Rogachev, eds: Paleolit Kostenki-

Borševskogo raiona na Donu [The Palaeolithic of the Kostenki-Borshevo area on the Don] (Leningrad, 1982).

PD

Koster North American prehistoric site located on thick alluvial and colluvial deposits along the eastern edge of the lower Illinois River in Greene County, Illinois. Large-scale excavations conducted during the 1970s revealed that these deposits contained at least 23 stratigraphically distinct cultural horizons dating from the Early Archaic to the Late Prehistoric periods (8000 BC–AD 1000). Investigation of these deposits yielded a continuous record of Holocene soil formation, deposition, and human occupation in west central Illinois. Of particular importance is the late Middle Archaic Helton phase dating from c.3800 to 2900 BC. Analysis of cultural materials from the Helton-phase occupation zones has provided important new insights on trends toward sedentism during the mid-Holocene.

T. Cook: Koster: an artifact analysis of two Archaic phases in West Central Illinois (Evanston, 1976); J. Brown and R. Vierra: ‘What happened in the Middle Archaic? Introduction to an ecological approach to Koster Site archaeology’, Archaic hunters and gatherers in the American Midwest, ed. J. Phillips and J. Brown (New York, 1983), 165–95; E. Hajic: Koster Site archaeology I: stratigraphy and landscape evolution (Kampsville, 1990).

RJE

Kot Diji Type-site of the Kot Dijian, a local culture which preceded the emergence of the INDUS CIVILIZATION. The site is located on an ancient flood channel of the Indus River, about 40 km east of MOHENJO-DARO, and was excavated by F.A. Khan in 1955–7. Sixteen main occupation levels have been identified at Kot Diji; the three uppermost levels date to the Mature Indus period (c.2600–1900 BC), including the remains of mudbrick structures containing typical HARAPPAN ceramic forms, steatite seals, terracotta figurines and copper implements. The 13 earlier levels belong to the ‘Kot Dijian’ period (roughly equivalent to the preand early Harappan phases elsewhere in the Indus region), which is dated by three calibrated radiocarbon dates to the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. A thick layer of charred materials separates Kot Dijian from Harappan materials, but it is uncertain whether this apparent disaster was natural or caused by human activity. A large stone and mud-brick perimeter wall was constructed early in the Kot Dijian period, enclosing 5 m thick deposits of superimposed structures.

Typical Kot Dijian artefacts include terracotta figurines, ground stone tools and chert sickle-blades and projectile points, as well as wheel-made ceramics, buff or red in surface colour and decorated with black or brown paint. Distinctive decorative motifs on Kot Diji ceramics include bands of wavy lines and fish-scale patterns. Ceramics in the Kot Diji style occur at a number of contemporaneous sites in the lower Indus area and beyond, including HARAPPA, AMRI, Gumla and Rahmen Dehri (Agrawal 1982).

F.A. Khan: ‘Excavations at Kot Diji’, PA 5 (1965), 11–85; D.P. Agrawal: The archaeology of India (Copenhagen, 1982), 129–35.

CS

kouros and kore (pl. kouroi, korai) Life-size marble sculptures of nude young men (kouroi) and dressed maidens (korai) produced in archaic Greece from the early 6th century BC until the early 5th century BC. The early kouroi reveal the strong influence of Egyptian conventions for standing male statues – stiff upright posture, strongly symmetrical except for one foot placed in front of the other – but the canon develops to form the basis of classical Greek sculpture. Some of the kouroi seem to have been offerings to the Gods Apollo and Poseidon, while the korai were strongly associated with the cult of Athena at Athens.

RJA

Kuang-han see SAN-HSING-TUI

Ku Bua see DVARAVATI CULTURE

Kudaro Group of stratified cave-sites on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus, in Southern Ossetia, Georgia. The faunal remains at each of the Kudaro sites are dominated by cave bear. The lower levels contain an ACHEULEAN-type assemblage, recently dated by means of THERMOLUMINESCENCE to 360,000–350,000 BP (Lyubin 1993). The upper levels yielded typical LEVALLOISMOUSTERIAN assemblages, radiocarbon dated to 44150±2400/1850 BP (GrN-6079).

Kudaro 3 is situated in the same valley at 1564 m above sea-level. The lower layers contained Acheulean-type industries, overlain by Mousterian deposits. The low concentration of finds suggests that the cave acted as a temporary camp-site.

Tsona Cave is situated on the southern slope of Mount Bub, at an altitude of 2100 m, near the sources of the Kvirila river in Southern Ossetia.

AL-KUFA 343

Two lower levels contain Acheulean-type industries, while the upper levels produced Levallois-Mousterian assemblages.

V.P. Lyubin: Moust’erskie kul’tury Kavkaza [The Mousterian cultures of the Caucasus] (Leningrad, 1977);

––––: ‘Paleolit Kavkaza’ [The Palaeolithic of the Caucasus], Paleolit Kavkaza i Severnoi Aziii [The Palaeolithic of the Caucasus and Northern Asia], ed.P.I. Boriskovsky (Leningrad, 1988), 9–142; V.P. Lyubin: ‘Hronostratigrafija paleolita Kavkaza’ [The chronostratigraphy of the Caucasian Palaeolithic], Rossijskaja arheologija 1 (1993), 5–14.

PD

kudurru (Akkadian: ‘frontier/limit’) Type of Mesopotamian boundary stone in the form of a cone, oval or cylinder, decorated with reliefs depicting human figures and religious symbols, and often carved with cuneiform decrees or real estate contracts, as well as lists of threats to those who transgressed them. Textual references indicate that boundary stones were already in use in SUMERIAN times but they became particularly common in northern Mesopotamia during the KASSITE dynasty (c.1600–1100 BC) when the AKKADIAN term kudurru was introduced. Their inscriptions were often copied onto clay tablets and placed in temples, while the stones themselves served as physical tokens of land ownership, perhaps deriving originally from the rough boulders used to denote the edges of plots of agricultural land.

U. Seidl: ‘Die babylonischen Kudurru-reliefs’, Baghdader Mitteilungen 4 (1968), 7–220; I.J. Gelb, P. Steinkeller and R.M. Whiting: Earliest land tenure systems in the Near East: ancient kudurrus (Chicago, 1991).

IS

al-Kufa Islamic-period site in Iraq, which includes the only Umayyad period palace studied in the eastern Islamic world. The excavations carried out at al-Kufa in 1938, 1953 and 1956 were limited to the palace, which reflects the strong influence of SASANIAN architecture on early Islamic building. Its construction (in c.AD 670) is attributed very specifically to ðUbayd b. Abihi, the Umayyad governor of Iraq. This interpretation connects the textual evidence on ðUbayd’s wellknown career in Iraq as governor with the earliest palace on the site. While plausible, the association of structures and sites with specific individuals and events means that the earlier or subsequent life of a site tends to be ignored. The same process has occurred to some extent at AL-WASIT and to a degree is the result of excavating so that archaeology fills out the historical gaps, rather than

344 AL-KUFA

allowing the archaeology to lead the interpretation of the site.

M.A. Mustafâr: ‘Taqrîr awwalî ðan at-tanqîb fî’l Kûfa l’l- mawsim al-thâlith’, Sumer 12 (1956), 2–32. [translated into English by C. Kessler, Sumer 19 (1957), 36–65]; K.A.C. Creswell: Early Muslim architecture I/1 (Oxford, 1969), 46–58; H. Djait: ‘Al-Kûfa’, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edn (Leiden, 1971); ––––: Al-Kufa: naissance de la ville islamique (Paris, 1986).

GK

Kujavian barrows Polish earthen barrows of the late 5th and early 4th millennium BC, named after the region of Kujavia (in which they are concentrated). They consist of a trapezoidal or almost triangular mound that is higher and wider at the end oriented to the east. The eastern part of the mound usually covers an individual (occasionally paired or multiple) extended inhumation, which may be accompanied by a simple range of grave goods (collared jars, scrapers, arrowheads, amber beads etc.). The Kujavian graves are thus interesting exceptions to the – apparently – collective burials that are found in most monumental tombs in the Neolithic in Europe. Some of the Kujavian mounds may have contained a wooden chamber, or been built over the site of a wooden structure.

R. Joussaume: Dolmens for the Dead, trans. A. and C. Chippindale (London, 1988), 27–30.

RJA

Kuk swamp Situated near Mount Hagen in the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea, and dating from after about 9000 years BP, this site offers the earliest evidence for agriculture in Oceania. Kuk has provided insight into changing forms of subsistence and the mutual relationship between food production, exchange and social hierarchy.

Around 9000 years ago a clay fan was laid down in the swamp, possibly as a result of erosion on the slopes around the swamp caused by human clearance. This clay fan was drained artificially, providing the first evidence of a tradition of ditch digging in the Highlands which has continued until today (Bayliss-Smith and Golson 1992). The exact use of the swamp at this period is unknown, but it may well have been used for growing root crops such as taro, which respond well to wet conditions. Swamp cultivation is itself just one element in Pleistocene land management in the Highlands: there is also evidence in various areas of tree clearance through burning (Swadling and Hope 1992). Burning may have been carried out in order to sustain areas of grassland useful for hunting, which

were threatened by a rising tree-line after the glacial maximum.

The swamp was cultivated in a series of discontinuous phases, with major episodes of use around 6000 and 2000 years ago. These are associated with a complex system of mounds and drains, which together created a mosaic of wet and dry environments, good for growing root crops adapted to both sets of conditions. The discontinuous use of the swamp can be linked with farming practices in the region as a whole: the swamp was used at times of crisis in the dry-land farming system, and was abandoned when innovations (such as soil tillage or tree fallowing) extended the range and increased the yields from the dry-land sector.

Coincident with the first ditches at Kuk is the earliest evidence of the ‘wealth economies’ of the Highlands, in the form of polished axes and coastal sea shells. The link between production and exchange further explains the history of swamp use. The root crops grown in the swamp may have been used to support pig herds rather than people, at least from 6000 years ago onwards. In the Highlands today, the pig provides the point of articulation between subsistence on the one hand, and exchange and social standing on the other. Pigs are basic to all forms of exchange, and individuals wishing for success in exchange networks must intensify subsistence production to support more pigs. Those with access to swamp lands in the past (and present) could grow large amounts of root crops even when areas outside the swamp were degraded through over-exploitation.

It follows that the history of this early site cannot be explained simplistically in terms of nutritional requirements. Rather, the Kuk evidence shows that throughout the Holocene there has been a dynamic relationship between elements of the farming system and the demands of the social system that it was designed to provision.

J. Friedman and M. Rowlands, eds: The evolution of social systems (London, 1977), 419–55; J. Golson: ‘No room at the top: agricultural intensification in the New Guinea Highlands’, Sunda and Sahul, etc. J. Allen et al. (London, 1977); T. Bayliss-Smith and J. Golson: ‘A Colocasian revolution in the New Guinea Highlands’, Archaeology in Oceania 27 (1992), 1–21; P. Swadling and G. Hope: ‘Environmental change in New Guinea since human settlement’, The naive lands, ed. J. Dodson (Melbourne, 1992).

CG

Kuldura Site in the Southern Tadjikistan depression offering the earliest evidence for hominid presence in Central Asia. Discovered and studied