A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

second cataract northwards up to the region of KOM OMBO. Dated to the period between about 18,000 and 15,000 BC, the Halfan assemblages include some unusually small tool types, manufactured with an unusual LEVALLOIS technique and used to produce compound tools such as harpoons and arrows. The encampments generally appear to be smaller than those of their KHORMUSAN predecessors.

A.E. Marks: ‘The Halfan industry’, The prehistory of Nubia I, ed. F. Wendorf (Dallas, 1968), 392–460.

IS

half-life The time taken for half of a given number of atoms of a radioactive isotope to decay e.g. the half-life of 14C (see RADIOCARBON DATING) is 5730 years.

Hallstatt Cultural phase of the late Bronze Age and the first part of the Iron Age in central Europe, named after a site close to Lake Hallstatt near Salzburg in the Austrian Alps. The site itself consists of the remains of a large cemetery, in an area made rich from the Bronze Age onwards by saltmining – there are many ancient mine galleries in the locality. The inhumations and cremations (over 2000 burials have been found) are associated with numerous grave-goods, including pottery, finely made swords and other weaponry, horse fittings, and ornaments such as FIBULAE.

Following the German archaeologist Paul Reinecke, who first classified the material from

HALLSTATT 265

Hallstatt, it is conventional to divide the Hallstatt period into Hallstatt A (1200–1000BC) and Hallstatt B (1000–800/750 BC) in the later Bronze Age; and Hallstatt C (800/750–600 BC) and Hallstatt D (600–450 BC) in the early Iron Age. The Hallstatt is also often broken up geographically into an ‘east’ Hallstatt (Austria, Poland etc) and ‘west’ Hallstatt (south Germany, east France).

Hallstatt A and B belong to the period of the URNFIELD COMPLEX of the later Bronze Age. This era is characterised by cremation burial in large pottery urns, often with short cylindrical necks and wide bodies. Grave goods include swords in range of standardized shapes – those discovered at the site of Hallstatt, as elsewhere, were often extremely finely made and decorated (e.g. amber pommels) – and a range of bronze pins and other ornaments. Although urnfield burials are not much differentiated in terms of grave structure, the number and richness of grave goods varies greatly and presumably reflects a social elite. A quite specific range of symbols was used in bronze decoration, including sun symbols, waterfowl and wagons. Unlike the cemeteries, settlements are not well documented but seem to consist largely of groups of farmsteads; excavations at one site at Hascherkeller in Lower Bavaria indicate that a range of crafts (weaving, bronze ornament casting, potting) were carried out even at smaller settlements (Wells 1993).

Hallstatt C marks the beginning of the Iron Age, during which iron implements and weaponry

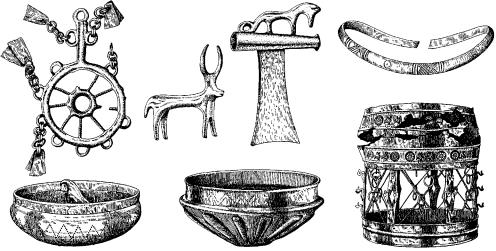

Figure 18 Hallstatt Selection of objects found in Tomb 507 at Hallstatt, c.7th century BC. Source: Trésors des princes celtes, exh. cat. (Paris, 1987), fig. 47a.

266 HALLSTATT

gradually replace bronzes, and central Europe begins to reveal contact with Italy, perhaps facilitated by earlier trade in salt. Inhumation burial under barrows replaces cremation burial, and burials are more strongly differentiated by wealth. Hallstatt D is the period of the great Hallstatt princely burials, which present extremely rich inventories of gravegoods as well as four-wheeled funerary carts – an especially elaborate example is the HOCHDORF cart, covered in iron sheeting. However, many decorative objects continue to use the typically Hallstatt motifs of the waterbird, sun and wagon; Reinecke contrasted this early Iron Age Hallstatt material culture with the material in the succeeding LA TÈNE style (the classic period of CELTIC ART), which evolved after c.450BC and gives its name to the second half of the Iron Age.

Mediterranean trade and the growth of social complexity. The archaeology of the early Iron Age (Hallstatt D) in central and central-western Europe is dominated by a series of massive hillfort settlements, such as the famous HEUNEBURG and MONT LASSOIS hillforts, associated with a sequence of extremely rich princely burials such as those of KLEIN ASPERGLE or VIX. The hillforts of this period represent a complexity of organization in economy and society that outstrips anything seen before the 6th century BC; they are often regarded as ‘proto-urban’ in the sense that they demonstrate a concentration of population, a degree of planning in their layout or architecture, and specialised craft production centres. It is also during Hallstatt D (i.e. c.600–475 BC) that direct trading with the Mediterranean region and Mediterranean entrepots such as Massalia in southern France develops. The richer Hallstatt sites (e.g. Vix, Heuneberg) are often located near important river valley trading routes, particularly those that link northern and central Europe to the Mediterranean. The material culture of these sites is characterized by imports from the Mediterranean region, and by Mediterraneaninfluenced local production; in one of its building phases, the Heuneburg fortifications were rebuilt in mudbrick in a Mediterranean-influenced style. Much of the discussion of the early Hallstatt archaeological record centres on the question of whether the particularly rich and powerful chiefdoms of Hallstatt D arose as a direct result of trading relationships with the civilised world (e.g. Frankenstein and Rowlands 1978).

The prime example of an early Greek trading entrepôt, Massalia (or Massilia, now Marseilles) in southern France, was founded in the 6th century BC. The establishment of Massalia followed a Greek pattern of settling colonies and entrepots on the

coast near trading river systems – a pattern begun with the establishment of Al Mina on the Orontes in Syria before 800 BC, Naucratis on the Nile Delta in Egypt in the 7th century BC etc. Unlike these early colonies, but like other colonies established on the Spanish and Black Sea coasts in the 7th and 6th centuries, the contacts Massalia established with its non-urban hinterland had a fundamental impact on the political and economic structure of the region. In the case of Massalia, ‘luxury’ goods such as decorated bronzes, fine pottery and wine flowed north; archaeological evidence for the goods obtained by the Greeks is lacking, but perhaps they secured slaves, furs, salt and iron.

Many of the imported goods are connected with wine consumption (Greek painted cups, Etruscan flagons, bowls and kraters), and seem to have formed prestige goods for the local elites. It may be that this form of ‘conspicuous consumption’ reflects the importance of feasting and gift exchange between elites at such meetings in the establishment of social dominance. In one developed version of this argument (summarised in Nicholson 1989), it is posited that the Greeks initiated the ‘trade’ by presenting local chieftains with elaborate presents in exchange for access to raw materials. The local leaders then used these exotic gifts to enhance their prestige and passed on the material as gifts to subordinate leaders. It is argued, though impossible to prove, that the gift-giving and receiving became intensely competitive, leading to an inflationary spiral in the exchange economy, with local leaders demanding ever more costly items to gather and permit passage of goods. As they developed trading relationships with the region north of the Black Sea, and elsewhere in Europe, it is possible that the Greeks discovered a cheaper or less problematic source of goods. Whatever the cause, the trading/exchange relationship between the Greek world and the early Celtic chiefdoms ended in crisis: at the end of Hallstatt D centres such as the Heuneburg are destroyed or quickly decline. As the established prestige-goods economy of the west Hallstatt region sank in importance, elites of adjacent regions grew in strength and inventiveness: the Hallstatt/La Tène transition seems to mark a shift in regional power as well as a cultural and artistic evolution.

S. Frankenstein and M.J. Rowlands: ‘The internal structure and regional context of early Iron Age society in south-western Germany’, Institute of Archaeology Bulletin 15 (1978), 73–112; P.S. Wells: Culture contact and culture change: Early Iron Age Central Europe and the Mediterranean world (Cambridge, 1980); N. Freidin: The early Iron Age in the Paris Basin, BAR IS 131 (Oxford,

1982); P. Nicholson: Iron Age pottery production in the Hunsrück-Eifel-Kulture, BAR IS 501 (Oxford, 1989); M.L.S. Sorensen and R. Thomas: The Bronze Age-Iron Age transition in Europe, BAR IS 483 (Oxford, 1989); P.S. Wells: ‘Investigating the origins of temperate Europe’s first towns: Excavations at Hascherkeller, 1978 to 1981,

Case studies in European prehistory, ed. P. Bogucki (Ann Arbor, 1993), 181–203.

RJA

Hallur Prehistoric settlement on the Tungabhadra river in Karnataka, India, which was excavated by Nagaraja Rao in 1965. It consists of two phases: the Neolithic-Chalcolithic (early 2nd millennium BC) and the early Iron Age (BLACK- AND-RED WARE period; late 2nd millennium BC). Circular houses with earthen floors and interior hearths were found in the earlier phase, along with food remains dominated by cattle and domesticated millet. The iron artefacts recovered from the second phase have been identified as the earliest iron implements in southern India (Nagaraja Rao 1971: 139–41).

M.S. Nagaraja Rao: Protohistoric cultures of the Tungahadra valley (Dharwar, 1971).

CS

Hama (pre-Islamic) see ARAMAEANS

Hama (Islamic) Ayyubid and Mamluk citadel (11th–14th centuries AD), excavated in 1931–8. Still one of the most important Syrian TELLS so far studied, the Hama citadel – like other fortifications on the Islamic side of the frontier with the Crusaders – was rebuilt in the 12th century. The ceramics recovered were somewhat imprecisely recorded in terms of stratigraphy, but the excavation remains a central point of reference for the studies of Syrian ceramics of the 12th–14th centuries. The chronology of these ceramics is now being revised in the light of excavations at ALRAQQA, ðAna, Qalðat Jabar and other Syrian sites.

V. Poulsen: ‘Les Poteries médiévales’, Hama: fouilles et recherches de la Fondation Carlsberg 1931–38 IV/2 (Copenhagen, 1957), 115–283; D. Sourdel: ‘Hamât’, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edn (Leiden, 1971); A. Northedge et al.: Excavations at ðÂna (Warminster, 1988); C. Tonghini: Qalðat Jaðbar: a study of a Syrian fortified site of the late 11th–14th century (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 1995).

GK

Hamadan see MEDES

Hamangia culture Late Neolithic culture of the lower Danube Black Sea region (Romania and

HANG GON 267

Bulgaria) of the late 5th/early 4th millennium BC. Makers of a dark-coloured impressed and burnished pottery, the most famous site of the

Hamangia culture is the cemetery of ˇ

CERNAVODA

where 400 or so extended inhumations are accompanied by stone jewellery, Spondylus shell beads and stylized pottery figurines.

D. Berciu: Cultura Hamangia (Bucharest, 1966).

RJA

Hammamia see EL-BADARI

Han dynasty Chinese chronological phase dating from 206 BC to AD 220. Following the downfall of the short-lived empire of CH’IN, and the unsuccessful attempt of the aristocratic Hsiang Y to re-establish the old Chou form of federalism (see CHINA 2), Liu Pang (of peasant origin) finally defeated the former, and so established the empire of Han. The new centralized imperial form of government was gradually to take shape, with its marked emphasis on the roles of scholars and officials, and with the Confucian doctrine suitably applied to the exigencies of the new regime (see LU for brief discussion of Confucius). This general pattern persisted over the next two millennia. It was also during Han that the empire expanded over most of the area of present-day China, overland contacts with the civilizations of the West (including Rome) were first recorded, and tremendous progress was made in the arts, science, technology and commerce.

H.H. Dubbs: The history of the former Han dynasty, 3 vols (Baltimore, 1938–55); M. Loewe: Records of Han administration, 2 vols (Cambridge, 1967); Y Ying-shih: Trade and expansion in Han China (Berkeley, 1967); M. Loewe:

Everyday life in early imperial China (London, 1968); H. Bielenstein: The bureaucracy of Han times (Cambridge, 1980).

NB

Hang Gon Settlement site in the Dong Nai valley, southern Vietnam. The site was disturbed by a bulldozer and subsequently examined by Saurin in 1960, when the surface finds recovered included three sandstone moulds for casting an axe and ringheaded pins. A late 3rd millennium BC radiocarbon date from the organic crust on the surface of potsherd has been used to support an early date for bronze metallurgy in Southeast Asia, but there was no stratigraphic relationship between the dated material and the moulds.

E. Saurin: ‘Station préhistorique à Hang-Gon près Xuan Loc’, BEFEO 51 (1963), 433–52.

CH

268 HAOULTI-MELAZO

Haoulti-Melazo Axumite site in the Ethiopian highlands, located about 10 km southwest of the city of AXUM itself, which was excavated by Jean Leclant and Henri de Contenson during the 1950s. The principal building is a stone-built sanctuary in which numerous votive deposits have been found, including figurines representing domesticated animals and women. The pre-Axumite phase of the site has yielded South Arabian stelae, a pair of unusual limestone statues of seated women and an elaborate limestone throne, all of which indicate the cultural influence of South Arabia on the early development of the site.

J. Leclant: ‘Haoulti-Mélazo 1955–1956’, AE 3 (1959), 43–81; H. de Contenson: ‘Les monuments d’art SudArabe découverts sur le site de Haoulti (Ethiopie) en 1959’, Syria 39 (1962), 64–87; ––––: ‘Les fouilles à Haoulti-Mélazo en 1958’, AE 5 (1963), 1–52.

IS

Harappa Large urban site of the INDUS CIVILIZATION, dating to the 3rd millennium BC and located along the ancient course of the river Ravi, a tributary of the Indus, Pakistan. The total area covered by Harappa is about 150 ha, almost half of

Granaries |

|

|

R i |

v e r |

b e |

d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Working |

|

|

|

|

|

560 |

|

|

|

floors |

540 |

540 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

550 |

||

Workmen’s |

N. gateway |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

quarters |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

W. gateways |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Harappa Village |

||

560 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CITADEL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

terraces |

540 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

540 |

Mound AB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

560 |

|

|

|

|

540 |

|

|

560 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

550 |

|

|

|

|

550 |

550 |

|

|

|

560 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

570 |

|

|

|

Police |

|

|

|

|

Mound E |

560 |

550 |

|||

Cemetery 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

station |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

540 |

|

||

540 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cemetery R37 |

|

|

540 |

|

|

|

To Montgomery |

||

|

|

|

|

|

18 miles |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ruined |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Serai |

|

|

|

|

|

|

excavated buildings and cemetery |

|||||

|

To Mohenjo Daro |

fortification investigated in 1946 |

|||||||

|

400 miles |

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

inferred fortification |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

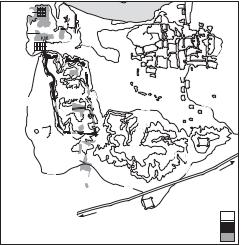

Figure 19 Harappa Plan of Harappa, type-site of the early Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley, showing the citadel mound, the mounds of the ruined lower town to the east, granaries and circular brick platforms (thought to be working areas for processing grain) to the north and, to the south, one of the few cemeteries known from the Harappan civilization (marked R37). Source: B. and R. Allchin: The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan (Cambridge, 1982), fig. 7.2.

which is taken up by two principal mounds (AB and E) and a number of smaller ones.

The site has been excavated by Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni (1920–25), Madho Sarup Vats (1925–34), Sastri (1937–41), Mortimer Wheeler (1946) and M.R. Mughal (1966). The current excavations (Meadow 1991) indicate continuous occupation from pre-urban Early Harappan to the post-urban Late Harappan period. Brick quarrying by 19th-century British railway builders resulted in disturbances of archaeological deposits and little is known of the original urban plan and architectural style. The architectural fragments that have been excavated provide evidence for multi-roomed rectangular structures built on unbaked brick platforms.

The structures and platforms at Harappa, constructed of standardized unbaked or fired bricks in the typical Indus 1:2:4 size ratio, were arranged along streets, and evidence for an extensive system of drains and wells also exists. The ‘citadel mound’ (AB), 18m high, consisted of massive mudbrick platforms and revetment walls, containing numerous wells, drains and fragmentary structural remains. Recent excavations on the eastern mound

(E) have revealed an enclosure wall and gateway, structures of baked and unbaked brick arranged into streets, and several superimposed pottery kilns. Evidence for production of a range of other specialized craft goods has been identified from surface remains. The excavations on Mound F uncovered circular fired-brick platforms interpreted by Wheeler (1947: 77–8) as threshing floors, and a large structure often construed as a granary.

Two distinct areas of burials have been excavated

– the Mature Harappan Cemetery R37, with more than 200 graves, and the post-urban Cemetery H. Artefacts from the Early Harappan levels include painted ceramics similar to KOT DIJI style ceramic vessels, as well as ceramic bangles, and animal and human figurines. Typical Mature Harappan artefacts include steatite seals, terracotta figurines, FAIENCE, shell, stone and ceramic ornaments and a wide range of wheel-made ceramic vessels. The types of pottery range from undecorated wares to black painted red ware storage and serving vessels, including the characteristic dish on stand, painted in naturalistic motifs including leaves, birds, fish, and herbivorous mammals, and trees. Late Harappan artefacts include the distinctive Cemetery H ceramic burial urns, painted in black, with common motifs including the peacock, bull, stars, leaves, and trees, within parallel black bands.

M.S. Vats: Excavations at Harappa (Delhi, 1940); R.E.M. Wheeler: ‘Harappa 1946: the defences and Cemetery

R37’, AI 3 (1947), 58–130; R.H. Meadow, ed.: Harappa excavations, 1986–1990 (Madison, 1991).

CS

Hargeisan Term used to describe the Late Stone Age industries of the Holocene in northern Somalia (Somaliland) and bordering Ethiopia. Like KENYA CAPSIAN, the Hargeisan industries are distinguished from the general run of the East African Late Stone Age (see WILTON) by the marked blade- and-burin element, the variety of types of point and, conversely, a less pronounced microlithic tendency.

J.D. Clark: The prehistoric cultures of the Horn of Africa

(Cambridge, 1954), 218–9.

JS

Hariri, Tell see MARI

Harmal, Tell (anc. Shaduppum) Small townsite of the Early Dynastic period (c.2900–2350 BC) at the eastern edge of modern Baghdad, which was excavated in 1946 by the Iraqi archaeologist Taha Baqir. It was a small but well fortified town incorporating three temples. Cuneiform tablets found at the site identify it as the ancient city of Shaduppum (‘the treasury’), a peripheral administrative centre of the Sumerian state of ESHNUNNA

in the DIYALA REGION.

T. Baqir: Tell Harmal (Baghdad, 1959).

IS

Harness (Edwin Harness Mound) The largest of 14 earthen mounds comprising the Liberty Earthworks, Ross County, Ohio (USA). It is associated with the Middle WOODLAND period (c.200 BC–AD 400, see HOPEWELL) cultural manifestation. Mound investigations began in the early 19th century and continued, intermittently, until the 1970s. The presence of numerous human burials, many containing exotic materials (such as copper, mica and galena), indicates that the Harness mound was a Hopewell mortuary facility. Archaeological investigations conducted in 1976–7 revealed the remains of a Hopewell civic-ceremonial building at the base of the mound. Radiocarbon dates suggest that this building was constructed in about AD 300.

N. Greber: ‘A comparative study of site morphology and burial patterns at Edwin Harness and Seip Mounds 1 and 2’, Hopewell archaeology: the Chillicothe conference, ed. D. Brose and N. Greber (Kent, OH, 1979), 27–38; N. Greber: Recent excavations at the Edwin Harness Mound, Liberty Works, Ross County, Ohio, MJA Special Paper No. 5 (Kent, OH, 1983).

RJE

HASANLU 269

Harran (pre-Islamic) see ASSYRIA

Harran (Islamic) Islamic site which is one of the few in the Turkish part of Jazira to have been excavated, although the results have never been properly published. The excavations mainly had the effect of clarifying K.A.C. Creswell’s studies of the Great Mosque, but had they been completed they would have been far more significant, since the site had survived very well, having avoided obliteration by Crusader period fortifications or modern settlement. Harran is far older than the Islamic period, but it is especially interesting as a site where paganism survived as late as the Caliph alMaðmun’s visit in AD 830. It was the last capital of the Umayyads under Marwan II (744–750) who built a mosque. Under Salah al-Din (Saladin), much of the Umayyad mosque was rebuilt between 1171 and 1184 and in this later period the site relates to Ayyubid and Mamluk sites in northern Syria and Seljuk sites in Anatolia.

D.S. Rice: ‘Mediaeval Harrân’, AS 2 (1952), 36–84; K.A.C. Creswell: Early Muslim architecture I/2 (Oxford, 1969), 644–8; G. Fehérvari: ‘Harrân’, Encyclopedia of Islam. 2nd edn (Leiden, 1971).

GK

Hasanlu Bronze Age to Iron Age settlement site located to the south of Lake Urmia in northwestern Iran, which was first excavated by Aurel Stein in 1936. The site was occupied from the early 3rd millennium BC onwards, and the artefactual record of the second half of the 2nd millennium BC was characterized by a distinctive style of burnished black or grey pottery. However, it was during the 11th–9th centuries BC that the settlement flourished, when it was the principal city of the Manneans, a non-Indo-European people whose territory surrounded Lake Urmia. Stratum IV, the Mannean phase, includes the remains of a large palace complex. The site was eventually destroyed in c.800 BC, probably at the hands of the rulers of URARTU. The American excavations between 1959 and 1977 have revealed the bodies of the city’s last defenders as well as weaponry, jewellery and metalwork. Among the metalwork, was a unique gold bowl decorated with motifs including deities, chariots and animals thought to be connected with HURRIAN mythology; the bowl is thought to be some centuries earlier in date than the phase of destruction.

A. Stein: Old routes of western Iran (London, 1940), 390–404; M.J. Mellink: ‘The Hasanlu Bowl in Anatolian perspective’, IA 6 (1966), 72–87; O.W. Muscarella: ‘Hasanlu in the 9th century’, AJA 75 (1971), 263–6;

270 HASANLU

––––: The catalogue of ivories from Hasanlu (Philadelphia, 1980).

IS

Hassuna, Tell Type-site of the Hassuna cultural phase of the 6th millennium BC, which has been found at a number of sites in northern Mesopotamia. The sequence of three Neolithic camp sites in the lowest excavated strata at Tell Hassuna, a few kilometres to the south of Mosul, constitute the earliest traces of settled life in the plains of northern Mesopotamia. The next phase in the site’s history is Hassuna Ib, which is probably contemporary with stratum I at the more southerly site of TELL ES-SAWWAN. The beginnings of the Hassuna culture (including elaborate mud-brick buildings and carved stone artefacts) have in fact been found at Tell es-Sawwan, rather than at the type-site itself. The people of the Hassuna phase typically relied on the cultivation of a variety of forms of grain (emmer, einkorn, bread wheat and barley) and built settlements consisting of streets of multi-room mud-brick houses with plastered walls; some of the dead (particularly children and adolescents) were buried, along with grave-goods (pottery and stone vessels and alabaster statuettes), under the floors of houses, although unidentified extramural cemeteries must also exist. There are two phases of Hassuna ceramics: ‘archaic’ and ‘standard’, the latter being more skilfully decorated and painted in a thicker brown paint. Tell Shemshara, a settlement in the lower Zab valley, is an aceramic version of the Hassuna culture, with no evidence of pottery until the onset of the Samarra phase in c.5600BC.

S. Lloyd and F. Safar: ‘Tell Hassuna’, JNES 4 (1945), 255–89; C.S. Coon: ‘Three skulls from Hassuna’, Sumer 4 (1950), 93–6; T. Dabagh: ‘Hassuna pottery’, Sumer 21 (1965), 93–111; P. Mortensen: Tell Shimshara: the Hassuna period (Copenhagen, 1970).

IS

Hassuna period see HASSUNA, TELL

Hastinapura Large multi-mounded site, located along an ancient course of the Ganges river in modern Uttar Pradesh, India, which may have been the site of the capital of the Kaurava kingdom. It dates from the early 2nd millennium BC to c.AD 300 and is mentioned in the Mahabharata. A few features in the lowest excavated levels may date to

the OCHRE COLOURED POTTERY period (pre-

1200 BC). The site was reoccupied from c.200 BC until c.AD 300, with the construction of fired brick buildings oriented along cardinal directions;

materials from this period include wheel-made grey ware pottery vessels and Buddhist figurines.

B.B. Lal: ‘Excavations at Hastinapur and other explorations in the upper Ganga and Sutlej Basin, 1950–52’,

AI 14 (1958), 4–48; T.N. Roy: The Ganges civilization

(New Delhi, 1983), 30–3, 84–6.

CS

Hathial see TAXILA

Hatnub Ancient name for the site of a set of travertine quarries situated 18 km southeast of elAmarna, on the eastern side of the Nile in Middle Egypt. The inscriptions, graffiti and archaeological remains of the workers’ settlements show that it was intermittently exploited for about 3000 years, from the reign of Khufu (c.2551–2528 BC) until the Roman period.

R. Anthes: Die Felseninschriften von Hatnub (Leipzig, 1928); I.M.E. Shaw: ‘A survey at Hatnub’, Amarna reports III, ed. B.J. Kemp (London, 1986), 189–212; ––––:

‘Pharaonic quarrying and mining: settlement and procurement in Egypt’s marginal regions’, Antiquity 68 (1994), 108–19.

IS

Hatra (el-Hadr) Pre-Islamic town-site in the central Jazira steppe about 250 km northwest of Baghdad, which emerged during the SELEUCID period (c.250 BC) as a small caravan town and meeting place. By the end of the 1st century BC it had become the capital of the kingdom of Araba, which lay at the edge of the PARTHIAN empire. The fortified town, covering an area of over 300 ha, became a centre of Parthian resistance to the Romans as well as an important cult centre, but in AD 233 it was captured by the Roman army. A few years later the town was sacked by the SASANIANS (some of whose siege equipment was excavated in the surrounding region) and was then effectively abandoned.

W.I. al-Salihi: Hatra (Baghdad, 1973); J.K. Ibrahim: PreIslamic settlement in Jazirah (Baghdad, 1986).

IS

Hattusas (Boghazköy) see HITTITES

Haua Fteah Large cave site, forming the roofed portion of an oval, sediment-filled limestone dissolution shaft (120 × 70 metres in size) not far from the coast on the northern slopes of the Gebel el Akhdar in Cyrenaica, northeastern Libya. In 1951–5, Charles McBurney excavated a 14 m deep trench inside the cave, consisting of a main cutting (11 × 9 m) and a basal deep sounding (2.5 × 1.5 m), still without reaching bedrock. In analysing this single stratigraphic column, McBurney concen-

trated on questions of chronology and long-term culture change, as reflected above all in the lithic artefacts, particularly their metrical attributes. Eighteen radiocarbon dates were obtained for the upper part of the sequence, but for the lower part McBurney relied upon a combination of other methods, and in doing so he pioneered approaches later to be tested and tried at sites such as KLASIES

RIVER MOUTH and BORDER CAVE. Interpolating

and extrapolating from the radiocarbon dates, and making use of estimated rates of sedimentation, McBurney calculated the age of the basal deposits at about 90–100,000 years BP; within the sequence there were warmer and colder episodes (as shown by sedimentological and faunal analyses) which he equated with the last interglacial, the last glacial, and the current interglacial periods respectively. The occurrence throughout the sequence of molluscs used for food (Patella coerula and Trocus turbinatus) permitted a palaeo-temperature analysis of their shells and the comparison of these results with those obtained on Mediterranean DEEP-SEA CORES where the foraminifera showed similar fluctuations; these in turn could be compared with Caribbean cores for which absolute dates had been obtained by the Pa/Th method (see URANIUM

SERIES DATING).

In McBurney’s view, the ‘industrial traditions’ at the Haua could be seen ‘growing and developing’, subject to ‘sudden outbursts or mutations’ and also to ‘decay and atrophy’, ‘in a manner strangely similar to the evolutionary history of organisms’ (McBurney 1967: 14). The various changes in the cultural sequence were almost invariably interpreted as evidence of migration and/or population replacement, although the ultimate origins for such movements usually remained unknown. Whatever imperfections or limitations may be detected in the excavator’s methods and theoretical assumptions, however, it remains true (as recognised by P.E.L. Smith) that the Haua is ‘the most important Upper Pleistocene site known in North Africa.’

C.B.M. McBurney: The Haua Fteah (Cyrenaica) and the Stone Age of the Southeast Mediterranean (Cambridge, 1967); P.E.L. Smith: ‘A key site on the Mediterranean’, Science 164 (1969), 705–8; C.B.M. McBurney:

Archaeology and the Homo sapiens sapiens problem in Northern Africa. Lecture in honour of Gerrit Heinrich Kroom

(Amsterdam–Harlem, 1977); A.E. Close: ‘The place of the Haua Fteah in the late palaeolithic of North Africa’, Stone Age prehistory, ed. G.N. Bailey and P. Callow (Cambridge, 1986), 169–80.

PA-J

HEIJO 271

Hawara Egyptian royal necropolis in the southeast corner of the Faiyum region, dominated by the 12th-dynasty pyramid complex of Amenemhat III (c.1800 BC), which was excavated by Flinders Petrie in 1888–9 and 1910–11. The mortuary temple immediately to the south of the pyramid may originally have been similar to the complex surrounding the Step Pyramid of Djoser (c.2620 BC) at SAQQARA. Known to Classical authors as the ‘Labyrinth’, the temple was visited by Herodotus, who gave an account of a complex of 3000 rooms and many winding passages. In the surrounding cemetery Petrie found some of the most impressive Faiyum mummy-portraits dating to the Roman period (c.30 BC–AD 395).

W.M.F. Petrie: Hawara, Biahmu and Arsinoe (London, 1889); ––––: Kahun, Gurob and Hawara (London, 1890);

––––, G.A. Wainwright and E. Mackay: The Labyrinth, Gerzeh and Mazguneh (London, 1912); A.B. Lloyd: ‘The Egyptian Labyrinth’, JEA 56 (1970), 81–100; D. Arnold: ‘Das Labyrinth und seine Vorbilder’, MDAIK 35 (1979), 1–9.

IS

Hazleton see COTSWOLD-SEVERN TOMBS

Hazor see CANAANITES

heavy mineral analysis Destructive analytical technique used in pottery studies, whereby heavy minerals (specific gravity >2.9) are separated from the lighter fraction by flotation of the crushed sample in a liquid of known specific gravity, such as Bromoform. The heavy minerals sink in this liquid and can then be examined using a polarizing microscope. The technique is mainly applied to sandy fabrics which may not lend themselves to examination in thin section since the heavy minerals are present in low concentrations relative to the mass of undiagnostic quartz. The heavy mineral suite (e.g. kyanite, zircon etc.) can be compared to the heavy mineral assemblage in sands from known localities and thus helps to provenance the pottery.

D.P.S. Peacock: ‘The heavy mineral analysis of pottery: a preliminary report’, Archaeometry 10 (1967), 97–100; D.F. Williams: ‘The Romano-British black-burnished industry: an essay on characterisation by heavy mineral analysis’, Pottery and early commerce, ed. D.P.S. Peacock (London, 1977), 163–220.

PTN

Hebrews see ISRAEL, ISRAELITES

Heijo Site of the palace and capital of the Ritsuryo state in Nara prefecture Japan from AD 710 to 784. The capital was laid out on a grid-plan after

272 HEIJO

the design of the Chinese capital of Chang-an and measured 4.3 × 4.8 km. The palace site was excavated from 1952 onwards, and was bought by the government to protect it from development in 1961. Plans of excavated palace buildings are reproduced in surface landscaping and some of the buildings and parts of the wall have been reconstructed using a combination of traditional and modern building techniques.

K. Tsuboi and M. Tanaka: The historic city of Nara: an archaeological approach (Paris and Tokyo, 1991).

SK

Heliopolis (Tell Hisn; anc. Iwnw) Egyptian site of the pharaonic period which is now largely covered by the northwestern suburb of Cairo. It was the site of the first known sun temple, dedicated to the god Ra-Horakhty and probably dating back to the early Old Kingdom (c.2600 BC). Excavations have also revealed a Predynastic cemetery, the tombs of the 6th-dynasty chief priests of Heliopolis, and a necropolis of ‘Mnevis-bulls’ dating to the late New Kingdom (c.1300–1070 BC). The only major monument still in situ is a pink granite OBELISK from the reign of Senusret I (c.1971–1926 BC). The obelisks now in New York and London (Cleopatra’s Needles) both date to the New Kingdom phase of the site (c.1550–1070 BC).

W.M.F. Petrie and E. Mackay: Heliopolis, Kafr Ammar and Shurafa (London, 1915); F. Debono: The predynastic cemetery at Heliopolis (Cairo, 1988).

IS

Helladic Term used to describe the Bronze Age of central and southern Greece, just as Cycladic and Minoan describe the Bronze Age cultural sequences of the Aegean islands and Crete, respectively. The Helladic is divided into Early (3000–2000BC), Middle (2000–1550BC) and Late (1550–1050BC), with Late Helladic corresponding to the

MYCENAEAN period.

RJA

Hell Gap Site in southeastern Wyoming which has given its name to a type of PALEOINDIAN projectile point and also to a complex of the PLANO Culture. The Hell Gap site consists of a stratified series of short-term campsites where bison was the predominant animal represented. Stratigraphy and point types at the Hell Gap site firmly established the Paleoindian sequence of Goshen, FOLSOM, Midland, Agate Basin, Hell Gap, Alberta, CODY, and Frederick complexes. Possible dwellings are represented by post-mould patterns at the Midland and Agate Basin levels and a circular arrangement

of rocks that were weights for a tipi in the Frederick level.

C. Irwin-Williams et al.: ‘Hell Gap: Paleo-Indian occupation on the High Plains’, PAnth 18 (1973), 40–53.

WB

Hembury (or Southwestern) ware Type of early Neolithic pottery of the very end of the 5th millennium and earlier 4th millennium BC, named after a causewayed enclosure in Devon, and found throughout southwest England (and as far east as Wiltshire). Hembury ware is in the form of roundbased open and rimmed bowls, often with lugs in a variety of shapes (and sometimes perforated). Peacock (1969) demonstrated that the gabbroic clay from which most Hembury ware is made comes from the Lizard Peninsular at the tip of Cornwall; it appears to have been a prestige ware, made by skilled potters and traded or exchanged over considerable distances.

D.P.S. Peacock: ‘Neolithic pottery production in Cornwall’, Antiquity 43 (1969), 145–9.

RJA

Hemmamieh (Hammamia) see EL-BADARI

Hemudo see HO-MU-TU

henge Ditched and banked circular and subcircular ritual enclosures of the British Neolithic and Bronze Age. The ditch is usually internal to the bank (unlike most historic defensive enclosures), although there are exceptions to this rule (notably Stonehenge); occasionally there is a bank both inside and outside the ditch. Henges can be as small as 10 m or less in diameter, while the most massive examples (e.g. the later examples in Wessex, notably DURRINGTON WALLS, Mount Pleasant, Marden, AVEBURY and Dorchester) can be over 400 m in diameter. There is usually one entrance (a ‘Class I’ henge), or two (a ‘Class II’ henge), most often opposed, entrances. Exceptional sites, such as Avebury, have up to four entrances. Class I henges seem to be the earliest, with examples dating from the late 4th millennium BC onwards, with Class II henges dating from the mid-3rd millennium into the late 2nd millennium. The Class II henges are also more likely to enclose major stone circles, and are often associated with GROOVED WARE pottery.

When excavated, many henges have revealed features such as internal settings of wooden posts. Exceptionally, at Durrington Walls and other major Wessex henges, these settings are concentric and massive and have been interpreted as the posts of huge wooden buildings, lying within the banks

of the henge. There may also be pits, cists and burials or associated standing stones. A relatively small number of henges enclose stone circles; where this is so, the ditch and bank of the henge may remain an imposing element of the site, as at Avebury, or become a relatively minor boundary marker as at STONEHENGE. (Slightly confusingly, the term henge is derived from the name of Stonehenge – ‘hanging stone’ – which as a site is by no means a typical example of the henge class of monument.) Henges occasionally have bank-and- ditch ceremonial avenues leading up to their entrances, as at Stonehenge, and are sometimes also associated with another class of enigmatic ritual monument, the CURSUS.

Henges occur across much of Britain, although there are marked regional concentrations – notably in southern Britain (Wessex) and the Orkneys (e.g. the Stones of Stenness and Brodgar). They seem to have replaced the of the earlier Neolithic in providing a ritual focus for communities. Although they are generally classed as ritual (i.e. non-domestic, non-utilitarian) structures, henges are so varied in their size, development over time, and the internal structures they exhibit, that the nature of that ritual must have varied considerably.

R.J.C. Atkinson et al.: Excavations at Dorchester, Oxon (Oxford, 1951); A. Burl: Stone circles of the British Isles

(Yale, 1976); A.F. Harding and G.E. Lee: Henge monuments and related sites of Great Britain: Air photographic evidence and catalogue, BAR BS 175 (Oxford, 1987).

RJA

Herakleopolis Magna (Ihnasya el-Medina; anc. Henen-nesut) Egyptian town 15 km west of modern Beni Suef, which reached its peak as the capital of the 9th and 10th dynasties during the 1st Intermediate Period. The surviving remains include two New Kingdom temples (one dedicated to the ram-god Harsaphes) and the nearby necropolis of Sedment el-Gebel incorporating a cemetery of the 1st Intermediate Period and Greco-Roman rock-tombs. There are also a settlement, cemetery and temple of the Third Intermediate Period (1070–712 BC), which have been excavated during the 1980s.

E. Naville: Ahnas el Medineh (Heracleopolis Magna)

(London, 1894); W.M.F. Petrie: Ehnasya 1904 (London, 1905); J. Padro and M. Pérez-Die: ‘Travaux récents de la mission archéologique espagnole à Hérakleopolis Magna’, Atken München 1985 II, ed. S. Schoske (Hamburg, 1989), 229–37; M. Pérez-Die: ‘Discoveries at Heracleopolis Magna’, EA 6 (1995), 23–5.

IS

HESY, TELL EL273

Hermopolis Magna (el-Ashmunein; anc. Khmun) Egyptian site located close to the modern town of Mallawi, which was the cult-centre of the god Thoth and capital of the 15th Upper Egyptian province. It was subject to extensive plundering in the early Islamic period, but there are still many remains of temples dating to the Middle and New Kingdoms, including a pylon (ceremonial gateway) constructed by Ramesses II (c.1290–1224 BC). The latter contained stone blocks quarried from the abandoned temples at the nearby site of EL-AMARNA (c.1353–1335 BC). There is also a comparatively well-preserved COPTIC basilica built entirely in a Greek architectural style and reusing stone blocks from a Ptolemaic temple.

G. Roeder: Hermopolis 1929–39 (Hildesheim, 1959); J.D. Cooney: Amarna reliefs from Hermopolis in American collections (Brooklyn, 1965); G. Roeder and R. Hanke:

Amarna-reliefs aus Hermopolis, 2 vols (Hildesheim, 1969–78); A.J. Spencer: Excavations at el-Ashmunein, 4 vols (London, 1983–93).

IS

Heshbon see HISBÂN

Hesy, Tell el- Settlement site on the southern Palestinian coastal plain, 26 km northeast of Gaza. The deepest strata date to the Early Bronze Age (c.3000–2100 BC) and the most recent archaeological remains comprise a Muslim cemetery of the 17th and 18th centuries AD. Flinders Petrie argued that the site was that of ancient LACHISH (now identified with Tell ed-Duweir), while William Albright suggested that it was the CANAANITE citystate of Eglon mentioned in the Bible (Joshua 10: 34–7), a theory which has still been neither proved nor disproved.

Investigated by Petrie in 1890, this tell-site was the first in the Palestinian region to be excavated using scientific stratigraphic techniques. The fortunate exposure of a large number of strata, as a result of floodwater erosion, enabled Petrie to establish an evolutionary typology (or SERIATION) of pottery types that could then be applied to the sections of stratigraphy in other parts of the site. He also used CROSS DATING, based on stratified Egyptian imports, to link the local chronology with that of Egypt. The site was subsequently excavated by Frederick Bliss, whose methods involved the pioneering use of a site GRID system involving a network of 5-foot squares. In 1892, Bliss’s excavations in one of the Late Bronze Age strata (‘City III’) unearthed a cuneiform tablet bearing a letter written in Akkadian by an Egyptian colonial official called Pa’pu. This document, roughly

274 HESY, TELL EL-

contemporary with the ‘AMARNA letters’, was the first item of Egyptian diplomatic correspondence to be excavated outside Egypt.

From 1969 onwards the site has been surveyed and excavated by the American Schools of Oriental Research (Fargo and O’Connell 1978; Blakely et al. 1980–93), with the principal aim of re-evaluating the stratigraphy described by Petrie and Bliss. In addition to clarifying many details of the site’s history, the American expedition has studied the changing climate and landscape of the coastal plain, in order to view the settlement in its full environmental and geomorphological context.

W.M.F. Petrie: Tell el-Hesy (London, 1891); F.J. Bliss: A mound of many cities (London, 1894); V.M. Fargo and K.G. O’Connell: ‘Five seasons of excavation at Tell elHesy’, BA 41 (1978), 165–92; J.N. Tubb and R. Chapman: Archaeology and the Bible (London, 1990), 26–9; J.A. Blakely et al., eds: Tell el-Hesi, 5 vols (Winona Lake, 1980–93).

IS

Heuneburg, the Early Iron Age (Hallstatt) hillfort near the upper reaches of the Danube in Baden-Württemberg, southern Germany. In most of its phases defended with timber and rubble fortifications, in the late 6th century BC the hilltop of the Heuneburg was (uniquely for Iron Age northern Europe) partly encircled with mud-brick walling on stone foundations and given projecting rectangular bastions. This is perhaps the most striking archaeological manifestation of the way in which the HALLSTATT elites copied Mediterranean inventions and styles, also shown in the imported items and artistic motifs and styles revealed in the princely burials of the period – e.g. HOCHDORF. (It seems doubtful whether mudbrick defences were suited to the wetter northern European climate, and it has been argued that the bastions were not usefully arranged – the innovations were abandoned in the next phase of building.) The Heuneburg settlement evidence includes amphorae, perhaps originally filled with wine, sherds of black-figure Greek vases (imported from the Greek trading centre of Massalia in southern France, founded c.600 BC) and other exotic items and materials such as coral. The Heuneburg may itself may have been a centre for the manufacture of elite items, including high quality wheel-made ceramics, and evidence of metal-working shops.

The Heuneburg is surrounded by a series of rich princely wagon graves, notably the 13m-high Hohmichele. The burials of this barrow (probably 6th century BC) were robbed, but fragments suggest a rich set of gravegoods and include a very rare find of

silk cloth. This Heuneburg-Hohmichele pattern of a defended settlement with rich satellite burials is repeated at other chiefly residences of the period such as the Hohenasperg near Stuttgart (the richest

grave here is KLEINASPERGLE) and MONT LASSOIS

in eastern France (associated with the VIX burial).

E. Gersbach: ‘Heuneburg – Aussensiedlung-Jüngere Adelsnekropole: Eine historische studie’, Marburger Beiträge zur Archäologie der kelten, 1 (1969), 29; W. Kimmig: ‘Early Celts on the Upper Danube: the excavations at the Heuneburg’, Recent archaeological excavations in Europe, ed. R. Bruce-Mitford (London, 1975), 32–65.

RJA

el-Hiba (anc. Teudjoi, Ancyronpolis) Ancient Egyptian settlement and necropolis comprising remains dating from the late New Kingdom to the Greco-Roman period (c.1100 BC–AD 395). The date of the foundation of the pharaonic town of Teudjoi is not known – the range of ceramics and depth of stratigraphy revealed by excavations in 1980 suggest that it was founded during the New Kingdom or earlier. In the 21st and 22nd dynasties (c.1070–712 BC) Teudjoi became an important frontier settlement between the two areas controlled

by the cities of HERAKLEOPOLIS MAGNA and

HERMOPOLIS MAGNA respectively. It was during this period that the large temple of Shoshenq I was built. After a period of decline the town regained its importance under the name of Ancyronpolis in the Greco-Roman period (c.304 BC–AD 395), when it developed into a military settlement.

Surface survey and sampling strategies. The earliest excavators at el-Hiba tended to focus either on the Greco-Roman settlement (Ranke 1926; Paribeni 1935) or on the cemeteries, where a number of caches of Greek and demotic papyri were found (Grenfell and Hunt 1906; Turner 1955). In 1980, Robert Wenke undertook a surface survey of the whole site and a set of test excavations among the settlement remains. This procedure involved the use of surface sampling, which was initially intended to take the form of a series of randomly selected transects (i.e. a form of ‘probabilistic sampling’, see SAMPLING STRATEGIES) from which deductions about the site as a whole might be made by statistical means. However, the ancient construction methods at el-Hiba had involved the movement of debris across the site and, in the postdepositional phase, varying degrees of looting and disturbance had taken place in different locations.

Wenke was therefore forced to adopt a more pragmatic non-probabilistic sampling design in which artefacts were collected from relatively