A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES 165

|

SWEDEN |

|

Barents |

Neolithic cultural areas |

|

|

|

|

Sea |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Bug-Dniestrian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tripolye (Cucuteni-Tripolye) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dniepr-Donetsian |

|

|

Kunda |

Antrea |

Oleneostrovski |

|

Sredni Stog |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Sarnate |

|

Narva |

|

|

Narva |

|

Sventoji |

Zvejnieki |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Upper Volga |

|

|||

|

Lubana |

|

R U S S I A |

|

||

|

|

Pit-and-comb |

|

|||

|

|

Usvyaty |

|

|

|

|

POLAND |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fatyanovo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sunghir |

|

|

Neolithic sites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Palaeolithic and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mesolithic sites |

|

Korolevo |

|

Khotylevo |

|

|

Scythian barrows |

|

|

|

|

|

Greek colonies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kostenki- |

Kapova |

|

|

|

|

|

Borshevo |

|

|

||

|

|

Cave |

|

Arzhan |

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

Karbuna Olbia |

Voloshski- |

|

|

Pazyryk |

||

|

|

Volgograd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vassil’evka |

|

|

|

|

|

Ak-Kaya Elizavetovka |

|

|

K A Z A K H S T A N |

|

|

Kiik-Koba/Starosel’ye/ |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

Murzak-Koba |

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

Black |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Sea |

Kudaro |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T U R K E Y |

|

Caspian |

|

|

|

|

|

Sea |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Azykh |

Kobystan |

|

0 |

500 km |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||

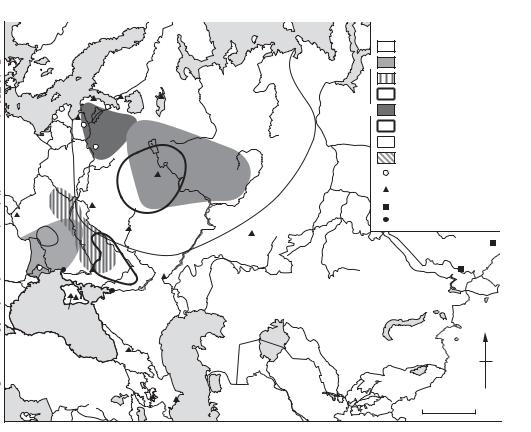

Map 21 CIS and the Baltic states Some major Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic sites in the CIS and the Baltic states, as well as selected Greek colonies and Scythian barrows.

in north Russia (OLENEOSTROVSKI), Latvia

(ZVEJNIEKI) and the Ukraine (VOLOSHSKI-

VASSIL’EVKA), and the evidence from these sites suggests both inter-group conflicts and a degree of social stratification.

Around 6500–6000 BP, pottery began to be produced on a large scale throughout much of European Russia, but many of the local economies retained a foraging character. The sites in the river valleys of Moldova and Ukraine (BUG-

DNIESTRIAN, DNIEPR-DONETSIAN) contained a

limited number of domesticated animal bones. This, and the imprints of cereals on the pottery, indicates contact with groups of farmers. However, sites belonging to cultural groups in central Russia (UPPER VOLGA) and the Eastern Baltic (NARVA) suggest a purely foraging economy.

In Azerbaidjan, south of Baku, Kobystan presents an impressive assemblage of paintings and engravings on the surface of rock outcrops on the coast of the Caspian Sea. The earliest group, pre-

sumed to have been executed during the early Mesolithic, consists of elongated (up to 1.5 m high) human figures. A later group, attributed to a timespan from the late Mesolithic to Neolithic, features hunting scenes with archers, dancing human figures, and ‘solar boats’. (The latest group, presumed to be Bronze Age, consists of stylized human and animal figures; amongst the latter, wild goats may be recognized.)

Around 4000 BC (6000 BP), Tripolye (see groups emerged in Moldova and southwestern Ukraine, later spread-

ing into the Middle Dniepr area. Initially, the Tripolye economy mixed farming with foraging, but by c.3500 BC it had become strongly agricultural; metallurgy and metal-working began to develop even in the early stages of the Tripolye culture (e.g. at KARBUNA). Simultaneously, GUMELNIT¸ A sites appeared in southern Moldova and the northwestern Pontic area. Concurrently with the Middle/Late Tripolye 5600–4800 BP

166 CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES

(4500–3400 BC), a cultural tradition known as the SREDNI STOG, characterized by horse-breeding, developed in the neighbouring steppe area. Various groups of foragers continued to live in the forested areas of East-European Plain. PIT-AND-COMB POTTERY, exclusively associated with foraging economies, spread across vast areas of central and northern Russia. The tradition of ‘pile dwelling’ emerged at a number of lake sites in the Western Dvina catchment (e.g. USVYATY).

From about 3000 BC, the Tripolye culture entered its final stage, characterized by a gradual disintegration of the single cultural tradition into a number of differently oriented metallurgical centres (e.g. Usatovo and Sofievka). The Tripolye complex ultimately ended in a total collapse of the agricultural economy: from 2800 BC, the predominantly pastoral PIT-GRAVE tradition spread through the South Russian steppes. At about the same time (c.3000–2300 BC), the Corded Ware tradition emerged, comprised of several local groups, widely spread across northwestern and central Russia. One of these groups (Fatyanovo) spread far to the east. Stock-breeding became an important element in the economy of many of these groups, but foraging remained the dominant strategy in a number of areas (North Belorussian sites in the Usyvaty area, late Neolithic sites in the Lubana area of Latvia, the sites belonging to the ‘coastal tradition’ in ŠVENTOJI and elsewhere).

In the forested area of European Russia, from the late 2nd to early 1st millennium BC, there seems to have been a gradual increase in the importance of stock-breeding as well as the development of local metallurgical and metal-working tradition. The main source of copper ores for these groups were the Uralian and South Siberian deposits. At some stage, the influence of Uralian groups which controlled the production and distribution of bronze tools became apparent in a wider area from Finland to Lake Baikal (e.g. the SEIMA-TURBINO complex). 2 Iron Age. Agriculture, allegedly of a swidden type (Petrov 1968), spread through the forested area of European Russia during the early Iron Age (1st millennium BC). A number of fortified settlements (GORODIŠCˇE) emerged, and several cultural groups are identifiable, e.g. STROKED POTTERY, DNIEPRDVINIAN, MILOGRADIAN and others (Sedov 1982).

The predominantly nomadic SCYTHIANS left numerous barrows in the ‘steppe corridor’ of southern Russia and Ukraine. The Scythian groups developed political and economic relationships with the Greek colonies and city-states on the Black Sea (e.g. OLBIA, Elizavetovka). Their cultural influence extended far to the east, as evidenced by the ‘royal

tombs’ in the Southern Siberia (PAZYRYK, ARZHAN). A number of predominantly agricultural groups – sometime called ‘agricultural Scythians’ and often regarded as ‘pre-Slavs’ – emerged in the forest-steppe area.

In the course of the 1st millennium AD, plough agriculture gradually spread into the forested areas of central Russia. The first archaeologically identifiable Slavic antiquities (with ‘Prague-type pottery’) emerged in Central and Eastern Europe in the 6th century AD. The first Slavonic urban centres (Ladoga, Novgorod, Kiev and others) emerged in the densely populated agricultural areas along the major waterways (Volkhov, Ilmen, Dniepr) in the 8th century AD. In the 9th century these areas became the target of Viking intrusions. In the second half of the 10th century AD, the greater part of Eastern Slavic groups united to form the Kievan Rus: the first major state in the region.

3 The history of archaeology in the region. The first archaeological excavations in Russia were made in Russia in the early 18th century during the reign of Peter the Great. The excavations of the Slavic barrows near Ladoga (Brandenburg 1985) and the acquisition of gold objects from Scythian barrows in Siberia (Rudenko 1962) are typical of this phase of enquiry. In 1846, the Russian Archaeological Society was founded in St. Petersburg. In 1859, the Imperial Archaeological Commission was set up within the Ministry of the Imperial Court. During the 19th century, Russian archaeologists concentrated on the excavation of classical sites: Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast (where the excavators included L. Stefani, V.V. Latyshev and M.I. Rostovtseff), SCYTHIAN sites (I.E. Zabelin and S.A. Zhebelev), Bronze Age sites in the Southern Russia, including the famous MAIKOP barrow (N.I. Veselovsky), and the PIT-GRAVE, CATACOMB and TIMBER-GRAVE tumuli (V.A. Gorodtsov); and the Slavic antiquities of Central and Northern Russia (N.E. Brandenburg, A.A. Samokvasov and D.Y. Spitsyn).

From the 1870s onwards, Russian scholars carried out the excavations of Palaeolithic sites at KOSTENKI-BORSHEVO (I.S. Polyakov) as well as in the Ukraine and in Siberia. During these years, Neolithic sites were discovered south of Ladoga Lake (A.A. Inostrantsev), as was the Fatyanovo cemetery (A.S. Uvarov), and the Bronze Age Volosovo site (I.S. Polyakov).

At a methodological level, V.A. Gorodtsov (1908) outlined the principles of typological classification of prehistoric materials. At the same time, Gorodtsov was one of the first to introduce the concept of an ‘archaeological culture’ to the Russian

discipline (Gorodtsov 1908). Both he and A.A. Spitsyn (Spitsyn 1899) adhered to the culturalethnic theory which equated ‘archaeological culture’ with ethnicity. On 18 April 1919, Lenin signed a decree establishing the Russian Academy for the History of Material Culture (RAIMK), which replaced the Imperial Archaeological Commission. The establishment of this centralized archaeological structure in the new Communist state was instigated by Nikolai Y. Marr (1865–1934), a Marxist linguist and archaeologist.

The structure of Soviet archaeology was repeatedly modified until the 1970s, when at least three hierarchical levels could be distinguished: AllUnion; Republic; and regional. All-Union institutions were entitled to carry out archaeological investigations on the whole territory of the USSR; they included the Research Institutes of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in Moscow, St. Petersburg (earlier Leningrad) and Novosibirsk. Each Soviet republic had either its own Institute of Archaeology (as in Ukraine and Georgia) or Departments of Archaeology within the Institutes of History (as in the Baltic republics, Belarus and elsewhere). Archaeological investigations were also carried out by major universities, and national (e.g. the State Museum of History, Moscow) and local museums.

The excavation techniques adopted in the USSR encouraged the large-scale exposure and stripping of archaeological layers. Great attention was attached to the identification of various types of structures, and to the distribution of artefacts within these structures. The minute application of this technique resulted in some outstanding achievements, such as the identification of Palaeolithic dwellings in the 1930s.

At a theoretical level, MARXIST historical materialism was the dominant epistemology in the Soviet archaeology. In accordance with this, archaeology was viewed as a part of history and was oriented towards the study of the evolution of society and culture. The Marxist approach greatly encouraged interpretations of a ‘sociological’ kind, and Soviet archaeology focused on the identification of three paramount elements in ancient cultures: technology, social organization and ideology. In the 1930s, Soviet archaeologists (e.g. Ravdonikas 1930) promoted the ‘stadial concept’ of prehistory, which viewed prehistory as a sequence of ‘socio-economic formations’ (a concept which greatly influenced V. Gordon Childe). In the 1930s and 1940s, P.P. Efimenko (1938a) and P.I. Boriskovsky (1950) advanced a theory according to which the basic social structure, characterizing the

CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES 167

Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, was an egalitarian ‘primitive herd’. This was replaced by a matriarchal ‘clan society’ at the transition to the Upper Palaeolithic. The remains of Palaeolithic ‘long houses’ were cited as one piece of evidence for this change. This theory was later much criticized: G.P. Grogor’ev (1968) convincingly argued that no major social differences are detectable through the Palaeolithic, that the nuclear family had already existed in the Lower Palaeolithic, and that there was no evidence for clan organization in the Upper Palaeolithic.

In the period after the Second World War, the Marxist approach took the form of a ‘sociological archaeology’ based on the early agricultural civilizations of Central Asia (e.g. Masson 1976; Alyokshin 1986). A different strand in Soviet archaeology concentrated on the analysis of prehistoric technology, and culminated in the works of S.A. Semenov, G.F. Korobkova and their disciples who pioneered the technique of

ANALYSIS (Semenov 1964; Semenov and Korobkova 1983). Like their counterparts in the West, Soviet archaeologists continually debated the proper aims of archaeology. According to one school of thought, e.g. Yu.N. Zakharuk (Zakharuk 1969) and V.F. Henning (Henning 1983) the prime objective of archaeology is to isolate an ‘ideal’ social model of human society – the ‘archaeological sources’ (such as artefacts) providing the means to discover this.

Another school of thought, often referred to as ‘strict archaeology’ and exemplified by L.S. Klejn (1991), G.S. Lebedev (1992) and their followers, focused their attention on the development of the theoretical base of archaeology and on the strict definition of basic concepts. This approach, similar in some ways to the ideas advanced by David Clarke

in his ‘ANALYTICAL ARCHAEOLOGY’, examines the

relations between artefact, attribute, type and culture. For example, ‘type’ in these schemes is often viewed as a ‘system of attributes’ (Lebedev 1979). Proponents of this school argue that only after completing an ‘internal synthesis’ can archaeologists proceed to ‘historical synthesis’, i.e. to the interpretation of archaeological entities in terms of social, economic, ethnic and cultural processes.

The dual approach of Soviet archaeologists to archaeological entities was particularly clear in their treatment of archaeological ‘cultures’ – ‘culture’ being universally recognized as the basic archaeological concept. The approach that stemmed from the theories of Spitsyn and Gorotsov, assuming a direct equation of archaeological cultures with

168 CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES

ethnicities, remains the leading paradigm among many Russian and Ukrainian archaeologists, such as A.Y. Bryusov (1956), Y.N. Zakharuk (1964), M.Yu Braichevsky (1965). This approach, in particular, informed those Soviet archaeologists who developed theories related to the origin of the Slavs (e.g. Tretyakov 1966; Lyapushkin 1961; Sedov 1982) and the SCYTHIANS (e.g. Artamonov 1974). However, another group of scholars (e.g. Zhukov 1929; Sorokin 1966; Grogir’ev 1972) tended to view archaeological cultures as purely taxonomic units.

General

P.P. Efimenko: Dorodovoe obšcˇestvo: Ocˇerki po istorii pervobytnogo obšcˇestva [Pre-clan society: essays on the history of primitive society] (Leningrad, 1938a); V.P. Petrov: Podsecˇnoe zemledelie [Swidden cultivation] (Kiev, 1968); V.I. Konivets: Paleolit Krainego Severo-Vostoka Evropy

[Palaeolithic of the extreme northeast of Europe] (Moscow, 1976); S.M. Tseitlin: Geologija paleolila Severnoi Azii, [Geology of the Palaeolithic of Northern Asia] (Moscow, 1979); L.L. Zaliznjak: Ohotniki na severnogo olenja Ukrainskogo Polesja epohi final’nogo paleolita. [Final Palaeolithic reindeer hunters of the Ukrainian Polesye] (Kiev, 1981); V.V. Sedov: Vostocˇnye slavjane v VI–XIII vekah [The Eastern Slavs in the 6th–13th centuries AD] (Moscow, 1982); O. Soffer: The Upper Palaeolithic of the Central Russian Plain (Orlando, 1985); V. Ranov: ‘Tout commence au Paléolithique’, DA 185 (1993), 4–13.

History of archaeology in the region

A.A. Spitsyn: ‘Rasselenie drevne-russkih plemën po arheologicˇeskim dannym’ [The settlement of early Slavic

tribes according to archaeological evidence]. ˇ

Zurnal ministerstva prosvešcˇenija (St. Petersburg, 1898/9), 301–40; V.A. Gorodtsov: Russkaja doistoricˇeskaja keramika

[Russian prehistoric pottery], Transactions of the 11th Russian Archaeological Congress (Kiev, 1901); ––––:

Pervobytnaja arheologija [Prehistoric archaeology] (Moscow, 1908); V.S. Zhukov: ‘Voprosy metodologii vydelenija kul’turnyh elementov i grupp’ [On the methodology of the identification of cultural elements and groups], Kul’tura i byt neselenija Central’no-Promyšlennoi oblasti [Culture and mode of life of the population of the Central Industrial District] (Moscow, 1929); V.I. Ravdonikas: ‘Za marksistskuju istoriju material’noi kul’tury’ [Marxist history of material culture], Izvestija GAIMK (1930/7), 3–4; P.P. Efimenko: Pervobytnoe obšcestvo: Ocerki po istorii paleolithiceskogo vremeni

[Primitive society: essays on the history of Palaeolithic epoch] (Leningrad, 1938b); P.I. Boriskovsky: Nacˇalnyi etap pervobytnogo obšcˇestva [The initial stage of primitive society] (Leningrad, 1950); A.Ya. Bryusov: ‘Arheologicˇeski kul’tury i etnicˇeski obšcˇnosti’ [Archaeological culture and ethnic entities], Sovetskaja arheologija 26 (1956), 5–27; I.I. Lyapushkin: ‘Dneprovskoe lesostepnoe levoberezˇ ’e v epohu zˇ eleza’ [The forest-steppe Dniepr left-bank in the Iron Age], MIAS 104 [Materials on the archaeology of the USSR]

(Moscow and Leningrad, 1961); S.I. Rudenko: Sibirskaja kollekcija Petra I [The Siberian Collection of Peter I], Svod arheologicheskih istochnikov [Collection of Archaeological Records], D 3–9 (Moscow, 1962); S.A. Semenov: Prehistoric technology, trans. N.W. Thomson (Bath, 1964); Yu. N. Zakharuk: ‘Problemy arheologicˇeskoi kul’tury’ [The problems of archaeological culture], Arheologija 17 (1964), 12–42; V.Yu. Braichevsky: ‘Teoreticˇny osnovy doslidzˇ en’ etnogenezu’ [Theoretical basis of ethnogenetic studies], Arheologija 2 (1965), 46–56; V.S. Sorokin: Andronovskaja kul’tura [The Andronovo Culture], Svod arheologicˇeskih istochnikov [Collection of Archaeological Records], 133/2 (Moscow, 1966); P.P. Tretyakov: ‘Finno-ugry, balty i slavjane na Dnepre i Volge

[The Finno-Ugrians, Balts and Slavs on the Dniepr and Volga] (Moscow and Leningrad, 1966); G.P. Grigor’ev:

Naccˇalo verhnego paleolita i proiskhozˇ denie Homo sapiens

[The beginnings of the Upper Palaeolithic and the origin of Homo sapiens] (Leningrad, 1968); Yu.N. Zakharuk: ‘O metodologii sovetskoi arheologii I eë problemah’ [On the methodology of Soviet archaeology and its problems], Sovetskaja arheologija 3 (1969), 11–20; G.P. Grigor’ev: ‘Kul’tura i tip v arheologii: kategorii analiza ili real’nost?’ [Culture and type in archaeology: analytical units or realities?], Transaction of the All-Union Session on the Results of Archaeological and Ethnographic Field Investigations in 1971 (Baku, 1972), 5–9; M.I. Artamonov: Kimmeriitsy i skify [The Cimmerians and Scythians] (Leningrad, 1974); V.M. Masson: Ekonomika i social’nyi stroi drevnih obšcˇestv [Economy and social pattern in ancient societies] (Leningrad, 1976); G.S. Lebedev: ‘Arheologicˇeskii tip kak sistema priznakov’ [The archaeological type as a system of attributes], Tipy v kul’ture [Types in culture], ed. L.S. Klejn (Leningrad, 1979), 74–87; V.V. Sedov: Vostocˇnye slavyane v VI–XIII vekah [The Eastern Slavs in the 6th–13th centuries AD], Arheologija SSSR (Moscow, 1982); V.F. Henning: Predmet i ob’jekt nauki arheologii

[The subject-matter of archaeology] (Kiev, 1983); S.A. Semenov and G.F. Korobkova: Tehnologija drevnih proizvodstv [Technology of prehistoric production] (Leningrad, 1983); N.E. Brandenburg: Kurgany Juznogo Priladoz’ja [Barrows of the south Ladoga area], Materialy po arheologii Rossii [Materials on the archaeology of Russia] (St. Petersburg, 1985); V.A. Alyokshin:

Social’naja struktura i pogrebal’nyi obrjad drevnezemledel’ceskih obscesty Srednei Azii i Bliznego Vostoka [The social structure and burial rites of early agricultural societies in Middle Asia and the Near East] (Leningrad, 1986); L.S. Klejn: Arheologicˇeskaja tipologija [An archaeological typology] (Leningrad, 1991); G.S. Lebedev: Istorija otecˇestvennoi arheologii 1700–1917 [History of Russian archaeology, 1700–1917] (St. Petersburg, 1992).

PD

Cishan see TZ’U-SHAN

Cliff Palace Largest cliff dwelling in the American Southwest, consisting of 217 rooms and 33 kivas, occupied by the ANASAZI in the 13th

century AD. It was discovered in 1888 by Richard Whetherill, a local cowboy and explorer of Southwestern prehistoric sites, while he was looking for stray cattle on Mesa Verde (now a National Park) in southwestern Colorado.

F. McNitt: Richard Wetherill: Anasazi (Albuquerque, 1957).

JJR

Clogg’s Cave Limestone cave and rock shelter in the Buchan region of Victoria, Australia. The basal deposits contain extinct megafauna, with no human associations, dating back to 23,000 BP. The earliest occupation is associated with the

TRADITION dating to 17,000 BP; increasing use of the cave between 13,000 and 9000 BP is associated with backed blades on chert, quartz and jasper. The cave is one of the few Pleistocene sites dug in Victoria.

J. Flood: ‘Pleistocene man at Clogg’s Cave: his tool kit and environment’, Mankind 9 (1974), 175–88; ––––:

Archaeology of the dreamtime (Sydney, 1983), 23–8.

CG

Clovis PALEOINDIAN culture, dating from c.10,000 to 9,000 BC, evidence of which occurs throughout much of North America. Clovis sites are identified by the presence of the distinctive Clovis fluted projectile point; these lanceolate bifaces are distinguished from later projectile points by a shallow flake scar or ‘flute’ that extends from the point’s base, approximately one-third up each face of the tool. Clovis is the earliest Paleoindian, big-game hunting culture of North America and is one of the complexes making up the LLANO tradition. On the basis of linguistic, dental and genetic evidence, Clovis is hypothesized to have been the New World ‘founding culture’. Traits shared with Palaeolithic sites in eastern Europe include large blades, end-scrapers, burins, unifacial flake tools, shaft wrenches, cylindrical bone points, flaked bone, red ochre and worked tusks. Examples of major sites are Naco, LEHNER and MURRAY SPRING (Arizona), BLACKWATER DRAW (New Mexico), Dent (Colorado) and EAST WENATCHEE (Washington state). Clovis people hunted a wide variety of Late Pleistocene animals, including now-extinct forms of mammoth and bison, as well as smaller animals like deer. Although poorly represented in the archaeological record, plant foods were undoubtedly important as well.

E.W. Haury et al.: ‘The Lehner mammoth site, southeastern Arizona’, AA 25 (1959), 2–34; G. Frison:

Prehistoric hunters of the High Plains (New York, 1991); D.

‘COASTAL NEOLITHIC’ (VIETNAM) 169

Stanford: ‘Clovis origins and adaptations: an introductory perspective’, Clovis: origins and adaptations, ed. R. Bonnichsen and K. Turnmire (Corvallis, 1991), 1–13; D. Meltzer: ‘Is there a Clovis adaptation?’, From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Palaeolithic Paleo-Indian adaptations, ed. O. Soffer and N. Praslov (New York, 1993), 293–310.

RJE/JJR

cluster analysis Techniques of MULTIVARIATE STATISTICS, with the common aim of dividing a collection of objects into groups or clusters on the basis of the similarity between each pair of objects. ‘Similarity’ can be regarded as the statistical equivalent of the spatial proximity of

objects (see MULTIVARIATE STATISTICS); groups

should ideally consist of objects which are close to each other but further from objects in other groups. There are many measures of distance; for continuous data the most common is Euclidean distance (the multivariate equivalent of a ‘crow-fly’ distance on a map, in contrast to, for example, distances measured along roads). Archaeologists experimented with various techniques in the 1960s and 1970s; the most commonly used now are k-means cluster analysis and Ward’s method. The main criticisms of cluster analysis are that it creates clusters whether any exist naturally in the data or not, and that the choice of the number of clusters is often arbitrary. The k-means method partly meets these objections by providing diagnostic statistics which can be used to suggest the best number of clusters in a DATASET. For case-studies see

ARMANT and MASK SITE.

R.M. Cormack: ‘A review of classification’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 134 (1971), 321–67; J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 173–86, 180–4 [K-means]; B.S. Everitt: Cluster analysis, 2nd edn (London, 1980), 16–7 [Ward’s method]; C.R. Orton:

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 46–55; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 196–208; M.J. Baxter: Exploratory multivariate analysis in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1993).

CO

‘Coastal Neolithic’ (Vietnam) Many coastal regions of Southeast Asia incorporate the remains of raised shorelines on which are located prehistoric settlements. These sites, dating from after c.4000 BC, were sited to take advantage of rich coastal resources, and excavations reveal the remains of shellfish and fish, as well as pottery vessels, polished stone artefacts including large hoes, and inhumation cemeteries. In Vietnam, these sites are referred to as ‘coastal Neolithic’, but to date there appear to be no surviving biological remains to

170 ‘COASTAL NEOLITHIC’ (VIETNAM)

indicate the presence of agriculture or stock raising. It might be that the inhabitants cultivated root crops, such as yam or taro, but equally they could have been sedentary hunter-gatherers. The bestknown ‘coastal Neolithic’ cultures in Vietnam are called after the sites of Da But, Cai Beo, Hoa Loc, Bau Tro and Quynh Van. Thac Lac (in central Vietnam), probably dating to c.3000–2000 BC, incorporates ceramics richly ornamented with parallel bands infilled with impressions recalling those found at PHUNG NGUYEN sites.

Two radiocarbon dates suggest that the upper layers of the six-metre-deep midden at Quynh Van (in northern Vietnam) belong to the mid-4th millennium BC. Excavations have uncovered 31 inhumation graves; unusually, for a site of this date, there were no polished stone implements. Although usually ascribed to the ‘Coastal Neolithic’, Quynh Van might just as well have been a sedentary settlement whose inhabitants exploited the wealth of the marine habitat rather than practising agriculture.

Ha Van Tan: ‘Nouvelles récherches prehistoriques et protohistoriques au Viet Nam’, BEFEO 68 (1980) 113–54.

CH

coatepantli (Nahuatl: ‘serpent-wall’) Mesoamerican structure of the Postclassic period (c.AD 900–1521) consisting of a long stone wall placed within or surrounding a ceremonial precinct, decorated with relief carvings of serpents and/or sacrifice. There are surviving examples at

TENOCHTITLAN and Tula (see TOLTECS).

PRI

Cochasquí Residential site of the so-called Cara Phase peoples in northern Ecuador during the Integration Period (c.AD 500–1450), consisting of 15 rectangular earthen pyramids with ramps and a large number of circular funerary platforms covering shaft-and-chamber tombs. Each of the pyramids had one or more perishable structures on their tops. Cochasquí was the residence of the chiefly and noble families of one of the small kingdoms that characterized late period highland Ecuador.

U. Oberem: Cochasquí: estudios arqueologicos, Colección Pendoneros, 3 vols (Otavalo, 1981); S.J. Athens: ‘Ethnicity and adaptation: the Late Period-Cara occupation in Northern Highland Ecuador’, Resources, power, and interregional interaction, ed. E. Schortman and P. Urban (New York, 1992), 93–219.

KB

the early Holocene until the appearance of pottery in c.AD 1–200. Cochise was defined in 1941 by Edwin Sayles and the geologist Ernst Antevs, on the basis of buried sites in the Whitewater Draw region of southeastern Arizona. The developmental sequence is divided into three stratigraphically distinct stages: Sulphur Spring (c.10,000–8000 BP), Chiricahua (up to 3500 BP) and San Pedro (c.3500–2000 BP). The relationship with CLOVIS remains unclear, although chronometric evidence does not support contemporaneity. The discontinuity between Sulphur Spring and Chiricahua is less than current stratigraphic and chronometric evidence indicates. The validity of Sayles’ ‘Cazador stage’, transitional between Sulphur Spring and Chiricahua, has been seriously questioned following the re-examination of deposits at the Whitewater Draw localities. Reinvestigation of BAT CAVE reliably dates the introduction of maize and squash to c.1200 BC. Cochise, long thought to have been ancestral to the MOGOLLON culture, is considered by many to have a similar link with the HOHOKAM. The major sites of the culture are VENTANA CAVE and Cienega Creek in Arizona, and Bat Cave and Tularosa Cave in New Mexico.

E.W. Haury: The stratigraphy and archaeology of Ventan Cave (Tucson, 1950); E.B. Sayles: The Cochise cultural sequence in southeastern Arizona (Tucson, 1983); N.H. Wills: Early prehistoric agriculture in the American Southwest (Santa Fe, 1988).

JJR

Coclé Culture which flourished between AD 500 and 1100 in the south-central Panama province of the same name. It is known primarily for its gold objects and polychrome pottery decorated with crested birds, dogs, reptiles, marine creatures and insects. The typically small Coclé sites, such as SITIO CONTE and Río Cano, are located along rivers; they appear to be the centres of chiefdoms. The structural remains are built of earth, and sites typically lack stone masonry; lines of stone pillars or columns in association with ‘altar’-like boulders are often found.

S.K. Lothrop: Coclé: an archaeological study of central Panama, Memoirs of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University 8 (Cambridge, 1942); O.F. Linares: Studies in Pre-columbian art and archaeology 17 (Washington, D.C., 1977) [section on ‘Ecology and the arts in ancient Panama’].

PRI

Cochise Archaic, pre-ceramic hunter-gatherer |

codices (sing. codex) Mesoamerican ‘books’ |

made from the beaten bark of the fig tree or deer |

|

culture of the southern American Southwest from |

skin. They were usually sized and coated with lime |

plaster, painted with HIEROGLYPHIC texts and then folded like a screen.

F.B. de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex: general history of the things of New Spain, 12 books in 13 vols, trans. A.J.O. Anderson and C. Dibble (Santa Fe, 1950–82); J.E.S. Thompson: The Dresden Codex (Philadelphia, 1972); K. Ross: Codex Mendoza: Aztec manuscript (Fribourg, 1978); ‘Special section: rethinking Mixtec codices’, AM 1/1 (1990).

PRI

Cody Complex One of several complexes of the PLANO culture of the PALEOINDIAN period in the northern Great Plains of the United States. The tool assemblage consists of projectile points, flake tools, scrapers, gravers, wedges, choppers, bifaces, hammer stones, and bone tools that are often found with bison kill and processing sites. Diagnostic tools are both Eden and Scottsbluff projectile points types as well as Cody knives. The Horner site in northwestern Wyoming is the type site for the Cody Complex, and is estimated to date between 8000–5500 BC. The Cody Complex lies stratigraphically between the Alberta and Frederick complexes at the site.

C. Irwin-Williams et al.: ‘Hell Gap: Paleo-Indian occupation on the High Plains’, PAnth 18 (1973), 40–53; G. Frison and L. Todd: The Horner site: the type site of the Cody cultural complex. (New York, 1983).

WB

cognitive archaeology Study of the ways of thought of past societies (and sometimes of individuals in those societies), as inferred from surviving material remains. Cognitive archaeology, or the archaeology of the human mind, can be recognized as a theme in the New Archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s, but it did not gain a distinct identity until the early 1990s. Like environmental archaeology, however, it is very much part of a wider enterprise of archaeology: the study of the whole human past. In humans, thought and action (or at least sustained action) are inseparable. For that reason Marcus and Flannery, for instance, prefer to speak of ‘holistic’ rather than ‘cognitive’ archaeology, in their approach to the study of Zapotec ritual at the Mesoamerican site of MOGOTE (Marcus and Flannery 1994: 55).

Whereas the so-called

ARCHAEOLOGY of the late 1980s and early 1990s was largely anti-processual in its aims and rhetoric, cognitive archaeology developed directly and without hiatus from the functional-processual archaeology of earlier decades. It represented a change of emphasis towards cognitive issues, which had been somewhat neglected after a few initial and

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY 171

programmatic statements in the first writings of the New Archaeology.

Certainly Kent Flannery in his early overview of Mesoamerican prehistory offered an early example of what he termed ‘contextual analysis’ (Flannery 1976), applied in the cognitive sphere, and in the same volume Robert Drennan considered the role of religion in social evolution, working very much in the functional-processual tradition. Flannery and Marcus have gone on to produce innovatory work on ritual and religion (Flannery and Marcus 1983; Marcus and Flannery 1994). Another early and significant contribution was Martin Wobst’s pioneering study of style and communication (Wobst 1977).

Cognitive-processual archaeology went beyond its functional-processual predecessor, however, by attempting to apply valid generalizations not only to material aspects of culture but also to the cognitive sphere. This undertaking recognized that ideology is an active force within societies and must be given a role in explanations – as Marxist and neo-Marxist thinkers have long argued. However, if generalizations about human cognitive behaviour are to be made, this must be on the basis of research, not through the formation and application of some a priori principle, in the manner of many MARXIST

ARCHAEOLOGISTS.

Cognitive archaeology, although working in the processual tradition, does not overlook the role of the individual. The notion of the ‘cognitive map’ is a useful one (Renfrew 1987), making explicit the world view which each individual carries in the mind’s eye. The shared beliefs and concepts of the community are in some ways the aggregate of those of the individuals who constitute it. This approach, which is termed by some philosophers ‘methodological individualism’ (Bell 1994), is common enough in the systematic social sciences. For instance the economic decisions of the individual are considered in the field of microeconomics, and their aggregate effects in macroeconomics. The philosophy of science has its own contributions to make to the understanding of the role of the individual in society.

Cognitive archaeology acknowledged, too, that material culture is to be seen as an active force in constituting the world in which we live. As Hodder (1986) has argued, individuals and societies construct their own realities, and material culture has an integral place within that construction. The scope of cognitive archaeology can be outlined in several ways (see Renfrew and Bahn 1991: 339–70). For instance, it may be divided into two very broad fields: pre-sapient and sapient. It is now well

172 COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY

documented that about 100,000 years ago our own species, Homo sapiens sapiens, became established in parts of Africa, and that by 40,000 years ago it had dispersed over much of the globe. The development of the cognitive faculties of the earlier hominids, which formed a crucial part in the processes leading to the emergence of Homo sapiens, constitutes the ‘pre-sapient’ area of cognitive archaeology. What, for instance, is the relationship between toolmaking and cognitive abilities? When and how did language emerge?

The sapient field of cognitive studies, on the other hand, is concerned with the human story over the past 40,000 years. The hardware (i.e. our brain power) may have changed little over this time-span, but the changes in our ‘software’ (i.e. ‘culture’) have brought about radical transformations. Organized hunting requires the deployment of sophisticated cognitive faculties (Mithen 1990), and it has been suggested that Palaeolithic CAVE ART was used as part of an educational process by which the young were initiated into and introduced to the society and social store of knowledge and experience which this necessitated. The emergence of settled village life and then of cities, the use of writing and of developing technologies such as metallurgy, the rise of organized religion and of widely influential ideologies, the development of states and empires: all of these have their cognitive aspects, as indeed do farming origins (see Hodder 1990). Moreover, although some of these developments may be traced in quite different parts of the world, each area followed its own trajectory of development: the ‘software’ was independently generated. Part of the challenge of cognitive archaeology is to analyse the ways in which the formation of symbolic systems, in each particular case, moulded and conditioned later developments.

The focus of cognitive archaeology is the special human ability to construct and use symbols (see also SIGN AND SYMBOL). A symbol is something which stands for, or represents, something else: ‘a visible sign of an idea or quality or of another object’ (Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 1925: 974 ‘symbol’). The word derives from the Greek ‘to place together’, and the notions of juxtaposition (of X by Y) and of metaphor (where X is equated with Y) are closely related. The cognitive-processual archaeologist focuses on the ways in which symbols were used. This may be contrasted with the attempt to seek the ‘meaning’ of symbols, which would generally be the object of the anti-processual or interpretive archaeologist (see CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY). The distinction is an important

one. As we shall see, both approaches inevitably rely upon the insights and intuitions of the modern investigator: the creative, and in that sense subjective, aspects of scientific enquiry are not in doubt. It is a common misconception of the scientific method, deriving largely from the polemic of Bourdieu, that it is somehow inhuman, mechanistic or lacking in creativity. On the contrary, the role of the individual, as noted above, has to be considered systematically, as the approach of methodological individualism allows (Bell 1994). For the cognitiveprocessual archaeologist, it is enough that this approach should generate insights into how ancient minds worked, and into the manner in which that working shaped their actions.

For the interpretive archaeologist, working in the grand tradition of idealists like Collingwood, this is not enough. One seeks, instead, to ‘enter the mind’ of early individuals through some effort of active empathy. This experience of ‘being’ that other, long-dead person, or at least undergoing an experience to be compared with theirs, is what characterizes the subjective, idealist and interpretationist approach of the antiprocessual and ‘post-modern’ archaeologist (see

POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY). The cogni-

tive-processual archaeologist is sceptical of the validity of this empathetic experience, and sceptical too of the privileged status which must inevitably be claimed by the idealist. As in the conduct of all scientific enquiry, it is not the source of the insight which validates the claim, but the explicit nature of the reasoning which sustains it and the means by which the available data can be brought into relationship with it. As Popper (1968) long ago emphasized, validation rests not upon authority but on testability and on the explicitness of the argumentation, even if testing is not always, in practice, an easy undertaking.

The scope of cognitive archaeology roughly coincides with the various ways in which humans use symbols:

1 design, in the sense of coherently structured, purposive behaviour;

2 planning, involving time scheduling and sometimes the production of a schema prior to carrying out the planned work;

3 measurement, involving devices for measuring, and units of measure;

4 social relations, with the use of symbols to structure and regulate inter-personal behaviour;

5 the supernatural, with the use of symbols to commune with the other world, and to mediate between the human and the world beyond;

6 representation, with the production and use of depictions or other iconic embodiments of reality.

The distinction between planning and design is not always a clear one, since so much human behaviour involves both. For instance the builders of the MALTESE TEMPLES of the 3rd millennium BC produced small models in limestone of the structures which they had built or were to build. It is difficult now to know whether the model preceded or succeeded the construction of the building itself. In either case, however, the model is a representation of the relevant part of the cognitive map in the mind of the modeller, and such material representations help to make more concrete the concept of the cognitive map itself. Of course cognitive maps are involved in all planning and design: in such cases they are models for the future. But if the former were the case (i.e. model before construction), this is a good example of both planning and design. In some cases, however, it is useful to emphasize the distinction between the two. For instance, in the production of stone tools (Gowlett 1984; Davidson and Noble 1989; Wynn 1991), raw material may have had to be acquired from some distant source. There is no doubt that the use of the material in some cases entails a deliberate journey undertaken at least in part to secure its acquisition. That implies planning, in the sense of timestructuring of a more complex kind. Comparable structuring of manufacturing processes has been considered in terms of the ‘chaîne opératoire’ (the ordered chain of actions etc., leading towards the transformation of a given material towards the manufacture of a product (Karlin and Julien 1994), and time structuring has been emphasized by Marshack (1991) in his consideration of Palaeolithic mobiliary art. In a different sense it was involved in the solar and lunar alignments of some of the European MEGALITHIC monuments and STONE CIRCLES (Heggie 1981).

The cognitive issues involved in tool production are often subsumed under the term ‘design’. It has long been assumed that the production of most artefacts, for instance of such stone tools as Acheulean handaxes, involves the use of a mental template, which serves to guide the person producing the artefact. But, as one example of cognitive archaeological investigation has shown, the production of an artefact type need not depend upon any sophisticated conceptualizing, nor need it presume the use of language (Bloch 1991). ‘Representation’, the sixth symbolic category in the list, comes very close to the literal meaning of the term ‘symbol’, as defined above. Of course not all symbols are visible

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY 173

or material – spoken words may reasonably be regarded as symbols – but no-one could doubt that all representations are symbols. We have perhaps not yet sufficiently considered the momentous nature of the step taken when clay was first modelled to produce, for instance, a small representation of the human form, or when a sharp implement was first used to carve the outline of an animal on a piece of bone. The creation and preservation of representations offers us great potential for considering a number of important cognitive steps, from the first application of pigment in some ice age cave to the great fresco cycles of the Italian Renaissance.

It is in the archaeology of historic periods, where written texts are available, that the most rapid progress in cognitive archaeology can perhaps be made. The problem in periods when such records are available is generally one of relating the archaeological and the textual evidence (for if elucidation of the material evidence carries pitfalls, that of the written text is still more perilous, as the critical theorists have so effectively shown). (It seems unnecessary, by the way, to follow the postmodernist fashion of regarding everything, including the archaeological record, as ‘text’: the archaeological record is usually a palimpsest, and the notion of ‘reading a text’ can hardly be applied to the randomly accumulated detritus of the centuries.) A message, if it is to be decoded, has to have been encoded in the first place. Here there is need for much further research on the semiotics of non-verbal communication. For the historical archaeologist (along with the Near Eastern specialist, the Classicist or the Mayanist) the challenge is to use the available texts in such a way that they can be applied to the inferences drawn from the material remains. The theoretical problems in reconciling such disparate bodies of evidence have yet to be systematically addressed.

There are numerous published case-studies of cognitive archaeology, ranging from research into the specific cognitive changes that characterized the emergence of modern humans (Mellars 1991) to the analysis of the symbolism of Classical Greek portraiture (Tanner 1992). The adoption of a cognitive approach often forces archaeologists to address fundamental questions which would previously have been ignored or avoided, such as ‘How religious were the ancient Egyptians?’ (Kemp 1995), ‘Is there a place for aesthetics in archaeology?’ (Taylor et al. 1994) and ‘How did ancient people perceive the landscapes in which they lived?’ (Bradley 1994).

E. Cassirer: An essay on man (New Haven, 1944); L.A.

174 COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY

White: The science of culture (New York, 1949); K.R. Popper: Conjectures and refutations (New York, 1968); R. Drennan: ‘Religion and social evolution in Formative Mesoamerica’, The early Mesoamerican village, ed. K.V. Flannery (New York 1976), 345–68; K.V. Flannery: ‘Contextual analysis of ritual paraphernalia from Formative Oaxaca’, The early Mesoamerican village, ed. K.V. Flannery (New York, 1976), 333–45; M. Wobst: ‘Stylistic behaviour and information exchange’, For the Director: essays in honor of James B. Griffin, ed. C.E. Cleland (Ann Arbor, 1977), 317–42; D.C. Heggie:

Megalithic science, ancient mathematics and astronomy in Northwest Europe (London, 1981); C. Renfrew: Towards an archaeology of mind (Cambridge, 1982); K.V. Flannery and J. Marcus, eds: The Cloud People: divergent evolution of the Zapotec and Mixtec civilizations (New York, 1983); J.A. Gowlett: ‘Mental abilities in early man: a look at some hard evidence’, Hominid evolution and community ecology, ed. R.A. Foley (London, 1984), 167–92; I. Hodder: Reading the past, 1st edn (Cambridge, 1986); C. Renfrew: ‘Problems in the modelling of socio-cultural systems’,

European Journal of Operational Research 30 (1987), 179–92; I. Davidson and W. Noble: ‘The archaeology of perception: traces of depiction and language’, CA 30 (1989), 125–56; I. Hodder: The domestication of Europe

(Cambridge, 1990); S. Mithen: Thoughtful foragers: a study of prehistoric decision making (Cambridge, 1990); M. Bloch: ‘Language, anthropology and cognitive science’, Man 26 (1991), 183–98; M. Donald: Origins of the modern mind (Cambridge, 1991); A. Marshack: ‘The Taï plaque and calendrical notation in the Upper Palaeolithic’, CAJ 1/1 (1991), 25–61; P. Mellars: ‘Cognitive changes and the emergence of modern humans’, CAJ 1/1 (1991), 63–76; C. Renfrew and P. Bahn: Archaeology, theories, methods and practice (London, 1991), 339–70; T. Wynn: ‘Tools, grammar and the archaeology of cognition’, CAJ 1/2 (1991), 191–206; J.J. Tanner: ‘Art as expressive symbolism: civic portraits in Classical Athens’, CAJ 2/2 (1992), 167–90; C. Renfrew et al.: ‘What is cognitive archaeology?’, CAJ 3/2 (1993), 247–70; J.A. Bell: Reconstructing prehistory, scientific method in Archaeology (Philadelphia, 1994); R. Bradley, ‘Symbols and signposts – understanding the prehistoric petroglyphs of the British Isles’, The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology, ed. C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow (Cambridge, 1994), 95–106; C. Karlin and M. Julien, ‘Prehistoric technology: a cognitive science?’, The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology, ed. C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow (Cambridge, 1994), 152–64; J. Marcus and K.V. Flannery: ‘Ancient Zapotec ritual and religion’, The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology, ed. C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow (Cambridge, 1994), 55–74; C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow, eds: The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology (Cambridge, 1994); M. Taylor, T. Vickers, H. Morphy and C. Renfrew: ‘Is there a place for aesthetics in archaeology?’, CAJ 4/2 (1994), 249–69; B.J. Kemp: ‘How religious were the ancient Egyptians?’, CAJ 5/1 (1995), 25–54.

CR

cognitive-processual approach see

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY

collapse, Lowland Maya see COPÁN;

LOWLAND MAYA

Co Loa see DONG SON CULTURE

colorimetric analysis Method of quantitative chemical analysis relying on the formation of a coloured compound in solution. The coloured compound is specific to the element being measured and it absorbs in the uv/visible region with an intensity proportional to concentration.

MC

Columnata see AFRICA 1

Commagene |

see NEMRUT DAGH |

cone mosaics |

see STIFTMOSAIK |

confidence interval Term used in statistical analysis to describe a range of values between which the value of a particular PARAMETER is thought to lie, together with a percentage representing the level of confidence with which this can be expressed

(see PARAMETER ESTIMATION). In BAYESIAN

STATISTICS this figure expresses a level or strength of belief; in classical statistics it represents the frequency with which repeated SAMPLES can be expected to include the true value of the parameter within their confidence interval, e.g. with a 90% confidence interval, 90% of samples would include the true value.

S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 301–9; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 70–3.

CO

confirmatory data analysis (CDA) Term used to describe such classical approaches to statistical analysis as HYPOTHESIS TESTING, as opposed to the more open-minded techniques of

EXPLORATORY DATA ANALYSIS (EDA).

Confucius (K’ung-tzu; Kongzi) see CH’U-FU;

LU

Con Moong Cave located on the Cuc Phuong massif, south of the Red River Delta in Vietnam. It has an unusually long stratigraphic sequence, beginning with the late Pleistocene culture and terminating in a layer ascribed to the HOABINHIAN. The early stone industry was domi-