A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfcrouched and extended inhumation. Most Yayoi burials have heads oriented eastwards.

T. Kanaseki et al.: ‘Yamaguchi-ken Doigahama iseki’ [Doigahama site, Yamaguchi prefecture], Nihon noko bunka no seisei, ed. Nihon Kokogaku Kyokai (Tokyo, 1961), 223–61 [in Japanese]; C.M. Aikens and T. Higuchi:

The prehistory of Japan (London, 1982), 204–6.

SK

dolmen see CROMLECH

Dong Dau Prehistoric settlement site covering 3 hectares, located just north of the Red River, which forms the type-site for the Dong Dau phase of the Vietnamese prehistoric sequence in the Red River valley. Excavations in 1965 and 1967–8 revealed a stratigraphy 5–6 m thick, the earliest phase belonging to the PHUNG NGUYEN culture. Such sites are rarely deeply stratified, and at Dong Dau it was possible to trace the development of the Phung Nguyen pottery tradition into the cultural phase named after Dong Dau itself. The Phung Nguyen tradition of ornamenting pottery with incised designs continued into this phase, and there was a vigorous bone industry, including the production of harpoons. Stone jewellery, such as pierced ear ornaments, were fashioned, and rice remains reveal an agricultural subsistence base.

Whereas the Phung Nguyen sites have very little evidence for copper-based technology, there is no doubt that metal casting became fully established in northern Vietnam during the Dong Dau culture, the sandstone and clay moulds as well as the cast axeheads and fishhooks being closely paralleled in northeast Thailand and at DOC CHUA. Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Dong Dau developed into the GO MUN culture, a period which saw a further increase in the number of bronze implements cast in the Red River valley.

Ha Van Tan: ‘Nouvelles recherches préhistoriques et protohistoriques au Viet Nam’, BEFEO 68 (1980), 113–54.

CH

Dongodien see EAST TURKANA; NDERIT

Dong Son culture One of the most complex manifestations of centralized chiefdoms in mainland Southeast Asia, originating in the 1st millennium BC in the lower valley of the Red River, Vietnam. The culture is characterized by its inhumation cemeteries, which contain an impressive range of bronze artefacts such as the famous Dong Son bronze drums.

In a handful of Dong Son cemeteries, the dead

DONG SON CULTURE 205

were interred in wooden boat coffins. Eight such burials have been found at Chau Can, in the Red River valley of Vietnam, where the coffin wood has been radiocarbon-dated to the unexpectedly early date of 1000–400 BC, although this may simply reflect the age of trees used to make the coffins. Apart from the human skeletons, much organic material has survived at Chau Can, including the wooden haft of a bronze axe, a bamboo ladle and a spear handle. In the Viet Khe burial, on the northern margins of the Red River delta, the boat coffin is 4.5 m long and contained over 100 artefacts, mainly of bronze. Calibrated radiocarbon dating suggests that this burial took place in about 400 BC, and may be compared to the burials at Chau Can, although in this case no primary interment was found.

Although most Dong Son archaeological sites comprise cemeteries, investigations at Co Loa (a moated settlement of the later 1st millennium BC located on the Red River floodplain, 15 km northwest of Hanoi) confirm the historic sources in revealing at least one large, central, defended site which has been widely interpreted as a chiefly centre. The moat at Co Loa surrounds three sets of ramparts, which have been dated by literary and archaeological evidence to at least the 3rd century BC. In 1982, excavations uncovered a Heger 1 bronze drum (one of four basic types of southeast Asian bronze drums, according to a descriptive system suggested by the Austrian F. Heger in 1902). The drum, like others of the Heger 1 type, was richly decorated with scenes showing warriors with feathered head-dresses, war canoes, houses and a set of four drums being played from a wooden platform. Co Loa also contained over 100 bronze socketed ploughshares or hoes, and a cache of several thousand bronze arrowheads was found outside the defended area. Other similar sites probably existed in other parts of the Red River delta area and the Ma valley (Higham 1989: 190–209).

Dong Son, the type-site of the culture, is located on the southern bank of the Ma River in northern Vietnam. It was first examined in 1924 by the French customs official Pajot, who encountered inhumation graves associated with bronze spearheads, decorated axes, ornamented plaques and drums. More recently, Vietnamese excavations have shown that there was a rapid transition from the Go Mun to the early Dong Son culture at this site. Decoration on the drums indicates that the people were given to ceremony and display in which the drums themselves played a significant part. It was formerly thought that the Dong Son bronze industry had its origins in China or even eastern

206 DONG SON CULTURE

Europe, but research on the DONG DAU and GO MUN cultures has provided clear evidence that it had local origins.

F. Heger: Alte Metalltrommeln aus Südost-Asien (Leipzig, 1902); O.R.T. Janse: Archaeological research in Indo-China III: The ancient dwelling site of Dong-S’on (Thanh-Hoa, Annam) (Cambridge, MA, 1958); Luu Tran Tieu: Khu Mo Co Chau Can (Hanoi 1977) [Vietnamese-language description of the excavation of Chau Can]; Ha Van Tan: ‘Nouvelles recherches préhistoriques et protohistoriques au Viet Nam’, BEFEO 68 (1980), 113–54; P. Wheatley: Nagara and commandery (Chicago, 1983), 91–3; C.F.W. Higham: The archaeology of mainland Southeast Asia

(Cambridge, 1989).

CH

Dongzhou see EASTERN CHOU

Dorestad Urban site in the Netherlands, the archaeological investigations of which constitute perhaps the most ambitious open-area study of a medieval site in Europe. L.J.F. Janssen carried out the first excavations in 1842 for the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden at Leiden; by 1859 Janssen was convinced that this was the site of the celebrated Carolingian port of Dorestad. Further campaigns were led by J.H. Holwerda in the 1920s. From a methodological standpoint, the massive 30 ha excavations from 1967 by W.A. van Es for the Dutch State Archaeological Service remain a remarkable undertaking.

Van Es, a Roman archaeologist by training, was faced with the destruction of the site by a new housing development. Convinced that the tradition of trenching early medieval emporia (e.g. BIRKA, Haithabu, IPSWICH and Kaupang) failed to provide any topographical data which, in turn, might demonstrate the function and political character of the site, he adopted mechanical means to expose as much of the settlement as possible. This controversial decision was not uniformly accepted at the 1972 Göttingen conference on early medieval towns, but the results affirmed van Es’ decision.

Dorestad lies beneath the modern small town of Wijk bij Duurstede where the most northerly branch of the Rhine splits into the river Lek and the Kromme Rijn. The 7thto 9th-century written sources indicate that it was located within the bifurcation of the rivers. The sources indicate that as early as the mid-7th century it was a mint for the gold trientes of the Frankish moneyer Madelinus. At this time it lay within Frisia, although it may have been under Merovingian dominance. By the early 8th century the centre lay in territory disputed between Radbod of Frisia and his Mero-

vingian neighbours. By 720 it was finally in Merovingian hands, and from then on served intermittently for the Franks. Throughout this period it is mentioned as a port at which Anglo-Saxon monks disembarked. Its role was undoubtedly developed under the Carolingians when it became one of the greatest centres in Europe.

Coins bearing a distinctive symbol of a ship were minted at Dorestad in the early 9th century, and its status as a toll station is mentioned in numerous sources. The coin evidence suggests that Dorestad’s economic decline had begun by 830, when its mint ceased to function. This coincided with the first recorded Viking attack of 834. From 841 or 850 it was actually in Viking hands. After this the raids continued, and by the 860s a combination of raids and the silting up of the river brought about its final abandonment. Its functions thereafter were taken over by Tiel and Deventer.

Van Es’ investigations indicate that Dorestad covered at least 40 hectares by the 9th century. It appears to have been composed of several zones. Alongside the river lay the harbour. Only part of this was excavated, showing that this consisted of plank walkways (each about 8 m wide) which were supported on wooden piles and extended out into the Kromme Rijn. Behind these lay a road approximately 3 m wide which ran along the original river bank.

On the other side of the road lay a line of buildings with their longitudinal axes towards the river. Each building would appear to have had its own walkway, an extension of the plot of land in which it lay. Possibly each building occupied an enclosed yard. Behind these buildings lay a cemetery at De Heul containing as many as 2350 individuals. In the centre of the cemetery was found a rectangular wooden building, about 8 × 15 m, which has been interpreted as a church.

North of the cemetery, beyond the riverbank settlement, lay a complex of farms, identified by their accompanying granaries. Each farm was situated in its own farmyard with its own well. The buildings themselves were bow-shaped, post-built structures similar to rural dwellings known from this region. Most buildings were internally divided into two sections of unequal length with opposing entrances in each side wall. Roads also ran through this part of Dorestad. To the south (i.e. to the west of the de Heul cemetery) lay another sector of the settlement. This contained another cemetery (De Engk) comprising a further 1000 inhumations. The surrounding sector remains undefined. South of this, occupying Middelweg, it has been proposed that there lay a Roman fort, from which the earliest

Merovingian trading settlement would have evolved.

Dorestad was pre-eminently a trading settlement founded about 630, which, to judge from the dendrochronological dates obtained from the wooden piles found in the river, was significantly enlarged in c.675. The influx of coins found in the excavations, many of them minted at Dorestad, indicates that its economic boom occurred between c.775 and c.825. The range of objects found at Dorestad indicates that it served the central Rhineland as an entrepot. Wooden barrels for transporting wine (re-used as the linings of wells) have been provenanced to the central Rhineland as has a huge proportion of the pottery (made either at Mayen or at production sites in the Vorgebirge Hills). Mill-stones, glass vessels and a range of minor stone objects were produced in the same region. Most scholars believe that these goods were shipped on via the Dutch archipelago and via the Frisian port of Medemblik, to places along the north German littoral, and as far north as the port of Ribe in western Jutland.

Products brought southwards remain a mystery. Only Baltic amber attests a two-way traffic. However, goods like slaves, furs, salt, honey, wax and possibly precious metals (to judge from the written sources) passed through the settlement en route for Merovingian and Carolingian centres to the south. Van Es’ decision means that Dorestad represents a key site in North Sea archaeology; it is a measure of economic and political activity in a formative age for the European community. In addition, its material culture is a well-dated point of reference for the archaeology of post-classical northwestern Europe.

W.A. van Es and W.J.H. Verwers: Excavations at Dorestad 1, the harbour: Hoogstraat I (Amersfoort, 1980); ––––:

‘Dorestad centred’, Medieval archaeology in the Netherlands, ed. J.C. Besteman, J.M. Bos and H.A. Heidinga (Maastricht, 1990), 151–82.

RH

Dorset culture Culture that occupied the Canadian Arctic from 550 BC until at least AD 1000. Best known for exquisite miniature carvings – perhaps the paraphernalia of SHAMANS – the Dorset culture appears to have been a more successful adaptation to the conditions of this region than the preceding

TRADITION cultures (from which it developed). This is demonstrated by the huge area occupied by Dorset groups, and by evidence that they had perfected winter hunting on the sea ice. However, by the time the THULE culture spread across the

DVARAVATI CULTURE 207

Canadian Arctic around AD 1000, the Dorset had largely or entirely disappeared for reasons that are not well understood.

M.S. Maxwell: Prehistory of the Eastern Arctic (Orlando, 1985).

RP

Dosariyah see ARABIA; PRE-ISLAMIC

Dotawo, Kingdom of, see GEBEL ADDA

double spout and bridge bottle Type of closed vessel common in much of Andean South America in which two spouts on the top of the vessel are connected by a handle.

dromos see THOLOS

Dura Europus |

see PARTHIANS |

Dur Kurigalzu |

see KASSITES |

Dur-Sharrukin |

see KHORSABAD |

Dur-Untash-Napirisha see ELAM

Duweir, Tell ed- see LACHISH

Dvaravati culture Complex polity which emerged in the central plain of Thailand between about AD 200 and 950. The name derives from two silver medallions found under a sanctuary at Nakhon Pathom in central Thailand, which proclaim that the building was the meritorious work of the King of Sri Dvaravati. Nakhon Pathom and U Thong are the best known of several large moated settlements; such sites contain substantial religious buildings which reveal a preference for Buddhism, although Hindu gods such as Siva were also worshipped.

U Thong was occupied at least from the beginning of the first millennium AD; the moats enclose an area of about 1690 by 840 m, and numerous foundations for Buddhist buildings have been uncovered. Excavations by J. Boisselier have revealed the foundations of an assembly hall and 3 octagonal STUPA bases. An inscription on copper, dated stylistically to the mid-7th century AD, records the accession of Harsavarman to the lion throne. It is feasible to see U Thong and other large moated sites, such as Nakhon Pathom, as competing centres within the polity of the Dvaravati culture. Excavations at Nakhon Pathom, the largest of the moated ceremonial centres, have concentrated on Buddhist buildings, and the nature of any secular

208 DVARAVATI CULTURE

structures remains to be clarified. Covering an area of 3700 × 2000 m, the site is dominated by a number of Buddhist sanctuaries.

At the site of Ku Bua, the moats and ramparts, which follow a roughly rectangular outline, cover an area of 2000 × 800 m, and are dominated by a central Buddhist temple; several other ruined structures are visible within the moats. The Buddhist temple and other buildings were decorated in stucco. Some representations show upper-class individuals or prisoners being chastised; the depiction of Semitic merchants stresses the importance of exchange to the Dvaravati economy.

The few inscriptions which have survived show that the vernacular language of the Dvaravati culture was Mon. The presence of an upper stratum in Dvaravati society is shown by the two terracotta ‘toilet trays’ from Nakhon Pathom, which bear numerous symbols of royalty. Early in the 11th century AD, the area came under strong influence from the expansionary and powerful rulers of ANGKOR, who probably exerted political control over the occupants of the Chao Phraya valley thereafter.

The early phases of the Dvaravati culture correspond to the FUNAN polities in the lower Mekong and trans-Bassac area of Vietnam, but the full development was contemporary with the ZHENLA CULTURE and the early period of Angkor. A series of competing polities centred on the large moated sites, rather than a single state, is the more likely interpretation of the political organization of the Dvaravati (see also MANDALA).

P. Dupont: L’archéologie Mi Mone de Dvaravati (Paris

1959); E. Lyons: ‘The traders of Ku Bua’, Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America 19 (1965), 52–6; J. Boisselier: Nouvelles connaissances archéologiques de la ville d’U-T’ong (Bangkok 1968); P. Wheatley: Nagara and Commandery (Chicago, 1983), 199–219.

CH

Dzibilchaltún Large LOWLAND MAYA city located in the dry northwestern corner of the Yucatán peninsula. Occupation extended from Middle Preclassic times into the Late Postclassic (i.e. c.1000 BC–AD 1400). The population declined in the Early Classic, peaking at about 25,000 during the Late Classic period, and dropped again in the Early Postclassic. With a large CENOTE at its centre, Dzibilchaltún consists of about 8000 structures arranged in numerous groupings, some joined by SACBES; many buildings of the Late Classic period (c.AD 600–900) feature PUUC-style architecture. The structural remains of the site cover nearly 20 sq. km, with rural agricultural populations living in the surrounding 100 sq. km. Located near the salt-producing regions of coastal Yucatán, Dzibilchaltún probably played an important role in the Maya salt trade.

E.W. Andrews IV: ‘Dzibilchaltun, a northern Maya metropolis’, Archaeology 21 (1968) 36–47; E.B. Kurjack:

Prehistoric lowland Maya community and social organization: a case study at Dzibilchaltun, Yucatan, Mexico

(New Orleans, 1974); E.W. Andrews V: ‘Dzibilchaltun’,

Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians I, ed. V.R. Bricker and J.A. Sabloff (Austin 1981), 313–41.

PRI

dzimbahwe see GREAT ZIMBABWE

E

Early Dynastic (Mesopotamia) One of the earliest periods of the Sumerian civilization (see SUMER), which was divided into three phases (ED I–III: c.2900–2350 BC) defined primarily by excavations in the DIYALA REGION. Also known as the ‘pre-Sargonic period’.

Early Dynastic (Egypt) The first two (or, according to some chronologies, the first three) dynasties of pharaonic Egypt, c.3000–2649 BC. Also known as the Archaic period.

Early Historical periods see JAPAN 5

early (‘archaic’) Homo sapiens The species

Homo sapiens has its origins some 400,000 years ago, although the first fossils attributed to our species are not actually ‘anatomically modern’, this being true only of the later subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens (see

ANATOMICALLY MODERN HUMANS). Early Homo

sapiens fossils from Petralona in Greece, Swanscombe in Kent, Heidelburg, Broken Hill/Kabwe (central Africa see SANGOAN) and the Dali skull from China exhibit a high cranial vault with associated reduction of the facial bones and teeth which sets them apart from HOMO ERECTUS. Brain sizes for these hominids fall within the modern human range at 1100–1400 cm3. Given their African and European distribution, it has been suggested that early Homo sapiens constituted the ancestors of both anatomically modern humans and NEANDERTHALS. Others wish to classify the Neanderthals separately as Homo neanderthalensis.

C.B. Stringer: ‘Human evolution and biological adaptation in the Pleistocene’, Hominid evolution and community ecology, ed. R. Foley (London, 1984), 55–84; G. Richards: Human evolution: an introduction for the behavioural sciences (London, 1987); C.S. Gamble:

Timewalkers: The prehistory of global colonization (London, 1993).

PG-B

Early Iron Age (East Africa) Widespread cultural complex with a related set of distinctive pottery wares most of which date to the early and

mid-1st millennium AD, although those in the region west of Lake Victoria date back as early as the latter part of the 1st millennium BC. The distribution excludes the drier, more northerly parts of East Africa and the Eastern Rift Valley and flanking high grasslands; it fits remarkably closely with that of Bantu languages in south-central as well as eastern Africa. Following the arguments of Posnansky, Oliver and Fagan in the early 1960s and the research thus provoked (see Soper 1971), it is generally held that this Early Iron Age (‘EIA’) complex indicates the rapid expansion of speakers of eastern Bantu with a new iron-based and agricultural economy. Its emergence from the older, pre-Iron Age western Bantu in the forest zone remains a subject of debate.

The East African Early Iron Age has several known regional variants, one of the most important of which is Urewe, found at sites around Lake Victoria and westwards to Rwanda, Burundi, the Western Rift Valley and the forest edge in Zaire. The type-site of Urewe (the exact location of which is more correctly called Ulore) is close to the Lake in western Kenya, where collections were made by Archdeacon W.E. Owen in the 1940s. Some occurrences of Urewe ironwork and pottery (formerly described as ‘dimple-based’) are about 2000 years old, but claims for much earlier dates, such as 500 BC or earlier, have generally been discounted. Apart from their ‘dimpled’ bases, Urewe and related Early Iron Age pottery vessels are distinguished by bevelled rims and decoration in patterns of grooves and scrolls.

Beyond the Eastern Rift Valley, towards the coast and extending southwards, the Early Iron Age is represented by the related Kwale pottery, beginning in about the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. Kwale pottery was first recognized and defined by Robert Soper (1967), the type-site being in the Kwale hills behind Mombasa. Other derivatives of Urewe further south in Tanzania and beyond have comparable dating in the early-mid 1st millennium AD (e.g. UVINZA and KALAMBO). The term ‘Mwitu tradition’ has been proposed recently for much of this widespread early Iron Age phenomenon. Before the

210 EARLY IRON AGE

end of the 1st millennium AD, however, as these agricultural and iron-using communities adjusted, stabilized and differentiated as regional Bantuspeaking groupings in their various local environments across sub-equatorial Africa, the ceramic continuity also broke up. Pottery groups of the later Iron Age and recent times vary from one region to another and generally contrast with those of the Early Iron Age.

M.D. Leakey et al.: Dimple-based pottery from Central Kavirondo, Coryndon Memorial Museum Occasional Papers 2 (Coryndon, 1948); R.C. Soper: ‘Kwale’, Azania 2 (1967), 1–17; ––––: ‘Early Iron Age sites in north-east- ern Tanzania’, Azania 2 (1967), 19–36; ––––:

‘Radiocarbon dating of “dimple-based ware” in western Kenya’, Azania 4 (1969), 148–53; –––– ed.: ‘The Iron Age in eastern Africa’, Azania 6 (1971) [whole volume]; D.W. Phillipson: The later prehistory of Eastern and Southern Africa (London, 1977).

JS

Early Khartoum see KHARTOUM MESOLITHIC

Early Transcaucasian culture see KURA-

ARAXIAN

Easter Island Easternmost Polynesian island, first settled around 1400 BP from central eastern Polynesia. Easter Island presents one of the poorest terrestrial and marine floras and faunas in the Pacific. Its prehistory is divided into three phases: early (1400–1000 BP), Ahu Moai phase (1000–500 BP) and the Huri Ahu phase (500 BP to European contact in AD 1722). The famous statues, AHU and temple complexes were constructed in the middle phase and may have been destroyed in the wars of the last phase.

P. McCoy: ‘Easter Island’, The prehistory of Polynesia, ed. J. Jennings (Canberra, 1979), 135–66; P.V. Kirch: The evolution of Polynesian chiefdoms (Cambridge, 1984), 264–78.

CG

Eastern Anatolian Bronze Age see KURA-

ARAXIAN

Eastern Chou (Tung-Chou; Dongzhou) Chinese cultural phase lasting from 771 to 255 BC, which was in many respects the most formative era in the history of China. It occupies the latter half of the Chou dynasty (1122–220 BC, see CHINA 2) which followed the shift of the ROYAL DOMAIN from its

location near Hsi-an to that of Lo-

yang.

The period is divided into two main eras: the Chu’un-ch’iu period (770–481 BC) and the Chan-

kuo period (480–255 BC). The former coincides with Ch’un-ch’iu Tso-chuan [The Tso commentary on the Ch’un-ch’iu], a literary source with detailed accounts of that era which, in the form we know now, has been transmitted from Han times. The latter period coincides with similarly transmitted literary sources such as the Chan-kuo-ts’e [‘Intrigues’ of the Warring States] and the Kuo-yü [Discourses of the States].

It was during the Eastern Chou period that sovereignty of the Chou kings gradually came to an end, while the major states were largely occupied with internecine warfare; one or another briefly gaining ascendency. Yet, at the same time, there was marked progress towards the foundation of the historico-literary culture together with the development of philosophical concepts that were to mould the future two millennia of ‘imperial’ China’s culture. Much of this cultural development was proscribed during the CH’IN dynasty (Ch’in from 255 BC had rapidly conquered the remaining states and established in 221 BC the short-lived Empire under its name), but then restored under the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220).

Very valuable finds relating to the cultures of the various MIDDLE STATES and to such ‘barbarian’ states as CH’U, WU, YÜEH, PA, SHU and TIEN have shed considerable light upon the manner in which both technological and artistic influences from the Middle States were adapted and modified by the ‘barbarian’ states. These peripheral regions, however, also influenced certain technological and artistic developments in the Middle States (Barnard 1987). The discovery of iron casting and the development of malleable cast-iron technology emerged early in the Eastern Chou period.

M. Hsiao: ‘Shih-lun Chiang-nan Wu-kuo ch’ing-t’ung- ch’i’ [Thoughts on the bronzes of the State of Wu from Chiang-nan], WW 5 (1984), 11–15; Li Hsüeh-ch’in:

Eastern Zhou and Qin civilizations, trans. Chang Kwangchih (New Haven, 1985); Chang Kwang-chih: The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven, 1986), 394–9; N. Barnard: ‘Bronze casting technology in the peripheral “barbarian” regions’, BMM 12 (1987), 3–37; D.B. Wagner: ‘Toward the reconstruction of ancient Chinese techniques for the production of malleable cast iron’, East Asian Institute Occasional Papers 4 (1989), 1–72;

––––: Iron and steel in ancient China (Leiden, 1993).

NB

East Turkana Area east of Lake Turkana (Rudolf) in northern Kenya, which has been celebrated since the 1960s for its volcanic-ash and lake beds containing Early Stone Age materials and Lower Pleistocene and Plio-Pleistocene fossils. With regard to the history of the discovery of early

hominid remains, the finds made in this region – at Koobi Fora and other sites – by Richard Leakey and Glynn Isaac followed up those at OLDUVAI (Tanzania) and in the OMO valley (Ethiopia). Apart from the controversy over the classification and dating of the remarkable ‘1470’ skull, generally held now to be a representative of HOMO HABILIS dated at about 1.75 million years old (see Reader 1988), this region has produced other Homo habilis and HOMO ERECTUS specimens (the latter from 1.5 million years), as well as both robust and gracile australopithecines (see AUSTRALOPITHECUS), some well over 2 million years old.

Y. Coppens et al., eds: Earliest man and environments in the Lake Rudolf basin (Chicago, 1976); G. Meave and R.E. Leakey, eds: Koobi Fora Research Project I: The fossil hominids and an introduction to their context, 1968–74

(Oxford, 1978); J. Reader: Missing links: the hunt for earliest man, 2nd edn (London, 1988).

JS

East Wenatchee Single component câche site on the upper Columbia River in eastern Washington state, western North America, which contained the largest CLOVIS fluted points ever found, as well as ‘preforms’, and bevelled bone artefacts. TEPHROCHRONOLOGY was used to date the câche: grains of volcanic ash from the eruption of Glacier Peak in the nearby Cascade Mountains dated at 9300 BC adhering to the lower face of the points indicate a date of deposition shortly after this eruption.

P.J. Mehringer, Jr.: ‘Clovis cache found – weapons of ancient Americans’, NGM (1988), 500–3; –––– and F.F. Foit, Jr.: ‘Volcanic ash dating of the Clovis cache at East Wenatchee, Washington’, National Geographic Society Research 6/4 (1990), 495–503.

RC

Eberdingen-Hochdorf see HOCHDORF

Ebla (Tell Mardikh) Town-site 55 km southwest of Aleppo in northern Syria, which flourished in the Early to Late Bronze Age. In its earliest phase Tell Mardikh was the site of a protohistoric village of the late 4th millennium BC, followed by an early protoSyrian settlement containing substantial remains of KHIRBET KERAK ware. The Bronze Age city, with an estimated population of many thousands, was divided into four main quarters, as well as an acropolis including palaces and administrative structures.

Between 1974 and 1976 Italian archaeologists excavated an archive of about 6000 fragmentary clay tablets, incised with texts written in a cuneiform script similar to that used in the roughly contem-

EDFU 211

porary Sumerian town of KISH, identifying Tell Mardikh as Ebla and casting light for the first time on the history of northern Syria during the late 3rd millennium BC (Pettinato 1981). The archive, written in both Sumerian and ‘Eblaite’, a previously unknown form of the Semitic family of languages (i.e. similar to Ugaritic and Hebrew), was found in the ruins of Palace G, dating to c.2400–2250 BC. Until the discovery of the archive very little was known about northern Syria before the 2nd millennium BC, and it had not been suspected that there were such powerful 3rd-millennium Syrian citystates interacting with the Early Dynastic cities of SUMER and northern Mesopotamia (e.g. LAGASH and MARI).

In the 23rd century BC the Bronze Age city was sacked by the early Akkadian ruler Naram-Sin, and by c.2000 BC it appears to have been completely destroyed. The city nevertheless continued to thrive in the Middle Bronze Age until it was sacked by the HITTITES in c.1600 BC, and there are numerous subsequent settlement strata, including traces of occupation as late as the 7th century AD.

C. Bermant and M. Weitzmann: Ebla: an archaeological enigma (London, 1979); P. Matthiae: Ebla: an empire rediscovered, trans. C. Holme (London, 1980); G. Pettinato:

The archives of Ebla: an empire inscribed on clay (New York, 1981).

IS

eboulis (éboulis) Fragments of naturally fallen rock which often form the bulk of the archaeological deposit in caves and rock shelters. The rate and type of eboulis deposition, and its subsequent alteration by natural processes, are often used as indicators of climate in the archaeology of the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe.

F. Bordes: A tale of two caves (New York, 1972), 11, 28–36; H. Laville et al.: Rock shelters of the Périgord (London, 1980), 51–73.

RJA

Eburran see KENYA CAPSIAN

Ecbatana see MEDES

Eda see EXPLORATORY DATA ANALYSIS

Edfu (anc. Djeb, Apollonis Magna) Egyptian site consisting of a large stone temple complex, dating to the period between the reigns of Ptolemy III and XII (c.237–57 BC), and the adjacent ruins of a city inhabited from the early pharaonic period until the Christian (Byzantine) and Islamic periods. The earliest remains at Edfu have made it the type-site

212 EDFU

for the ‘Edfuan’, a group of non-microlithic Palaeolithic industries in Upper Egypt, which are roughly contemporary with the HALFAN industry (the latter being found further to the south, in the Wadi Halfa area of Nubia). The temple of Horus at Edfu is the best-preserved major Ptolemaic religious structure in Egypt. The study of the inscriptions has enabled Egyptologists to reconstruct many of the details of the daily rituals within the temple, including the feeding, bathing and clothing of the cult-image of the god in his sanctuary (Fairman 1954).

M. de Rochemonteix and E. Chassinat: Le Temple d’Edfou (Paris, 1892; Cairo, 1918–); K. Michalowski et al.: Tell Edfou, 4 vols (Cairo, 1937–50); H.W. Fairman: ‘Worship and festivals in an Egyptian temple’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Manchester 37 (1954), 165–203; B.J. Kemp: ‘The early development of towns in Egypt’, Antiquity 51 (1977), 185–200; S. Cauville: Edfou (Cairo, 1984).

IS

Edfuan see EDFU

edge effects see NEAREST NEIGHBOUR

ANALYSIS

EDXRF see X-RAY FLUORESCENCE

SPECTROMETRY

Effigy Mound Culture Late WOODLAND peoples who lived in what is now Wisconsin (and parts of neighbouring states) in eastern North America from c.AD 600 to 1200. They built variously shaped mounds, and the name Effigy Mound Culture comes from the animal shapes of many mounds, although conical and linear mounds also occur. Burials and hearths are frequently found in these low, often large mounds. The mounds are usually clustered together in groups, typically in locally prominent places. They perhaps served as the focus of group activities for widely distributed, semi-sedentary populations.

W.M. Hurley: ‘The Late Woodland stage: effigy mound culture’, The Wisconsin Archeologist 67 (1986), 283–301; L.G. Goldstein: ‘Landscapes and mortuary practices: a case for regional perspectives’, Regional approaches to mortuary analysis, ed. L.A. Beck (New York, 1995), 101–21.

GM

Egypt (Arab Republic of Egypt; anc. Kemet, Aegyptus) The Egyptian section of the Nile Valley descends for 800 km from the Sudan border to Cairo, then continues for a further 240 km along each of the major Delta branches down to the Mediterranean coast. The modern country of

Palaeolithic |

700,000 – 5000 BC |

||||

Lower Palaeolithic |

700,000 – 100,000 BC |

||||

Middle Palaeolithic |

100,000 – |

30,000 |

BC |

||

Upper Palaeolithic |

30,000 – |

10,000 |

BC |

||

Epipalaeolithic (Elkabian, Faiyum B) 10,000 |

– 5500 BC |

||||

Predynastic |

|

5500 – 3000 BC |

|||

Badarian (Faiyum A,Merimda) |

|

5500 |

– 4000 BC |

||

Amratian (Merimda, el-Omari A) |

|

4000 |

– 3500 BC |

||

Early Gerzean (el-Omari B) |

|

3500 |

– 3200 BC |

||

Late Gerzean (protodynastic, Macadi) |

3200 |

– 3000 BC |

|||

Dynastic period |

|

3000 – |

332 BC |

||

Early Dynastic period (Dynasty 1–2) |

3000 |

– 2649 BC |

|||

Old Kingdom (Dynasty 3–6) |

|

2649 |

– 2150 BC |

||

1st Intermediate period (Dynasty 7–11) |

2150 |

– 2040 BC |

|||

Middle Kingdom (Dynasty 11–13) |

|

2040 |

– 1640 BC |

||

2nd Intermediate period (Dynasty 14–17) |

1640 |

– 1550 BC |

|||

New Kingdom (Dynasty 18–20) |

|

1550 |

– 1070 BC |

||

3rd Intermediate period (Dynasty 21–25) |

1070 |

– |

712 BC |

||

Late period (Dynasty 25–30) |

|

712 |

– |

332 BC |

|

Greco-Roman period |

|

332 BC – AD 395 |

|||

Macedonian period |

|

332 – 304 BC |

|||

Ptolemaic period |

|

304 – |

30 BC |

||

Roman period |

|

30 BC – AD 395 |

|||

Christian period (‘Coptic’) |

|

AD 395 – 641 |

|||

Islamic period |

|

AD 641 – |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 12 Egypt Chronology of Egypt.

Egypt, consisting of the Nile Valley, the Delta, the oases and the eastern and western deserts, is in an unusual geographical position at the junction of three continents. Its northern border faces towards Europe (across the Mediterranean), its southern and western borders are in Africa and its eastern border is separated from Western Asia only by the Sinai desert and the Red Sea.

1 Prehistory. Egypt’s earliest inhabitants appeared during the Palaeolithic period in the grasslands of northeastern Africa (c.700,000 BC). With the onset of a drier climate (c.25,000 BC) the Eastern and Western Deserts began to form, evidently forcing the early Egyptians to move into the Nile Valley. There is evidence at some terminal Palaeolithic sites in Egypt (e.g. WADI KUBBANIYA and TUSHKA) for an unexpectedly early phase of experimentation with plant domestication. In the EPIPALAEOLITHIC period (c.10,000–7000 BC) several semi-nomadic, hunting and fishing cultures emerged in the Western Desert (see NABTA PLAYA) and the Nile

valley (see ELKAB and FAIYUM REGION). By about

5300 BC, as the climate moistened, numerous

EGYPT 213

|

|

Mediterranean Sea |

|

|

N |

|||

|

Alexandria |

Tell el-Faracin |

|

|

Behbeit el-Hagar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mendes |

|

|

|

|

|

Sais |

|

|

Tanis |

|

|

|

|

|

Naukratis |

|

|

Qantir + Tell el-Dabca |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Tell Basta |

Tell el-Maskhuta |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Tell Atrib |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

Bitter Lakes |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Merimda |

|

|

Heliopolis |

|

|

|

|

|

Abu Roash |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Cairo |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Giza |

Macadi |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Abu Ghurob + Abusir |

el-Omari |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Saqqara |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Memphis |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Faiyum region Dahshur |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

el-Lisht |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Qasr el-Sagha |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tarkhan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meidum |

|

|

SINAI |

|

|

|

|

Hawara |

|

|

||

|

|

Gurob |

el-Lahun |

|

|

Serabit el-Khadim |

||

|

Herakleopolis Magna |

el-Hiba |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

h |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

u |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

Beni Hasan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

f |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Hermopolis Magna |

|

Deir el-Bersha |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

el-Amarna |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meir |

|

|

Hatnub |

|

|

|

|

|

Nile |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Deir el-Gebrawi |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Asyut |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

el-Badari |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hammamiya |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Akhmim |

|

Red Sea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Abydos |

Dendera |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hiw Semaina region |

||

|

|

|

|

|

el-Amra |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Naqada |

Deir el-Ballas |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Koptos |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Armant |

Luxor (Thebes) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gebelein |

el-Mocalla |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Esna |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hierakonpolis |

Elkab |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edfu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wadi Shatt er-Rigal |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gebel el-Silsila |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kom Ombo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elephantine |

Aswan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philae |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

100 km |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

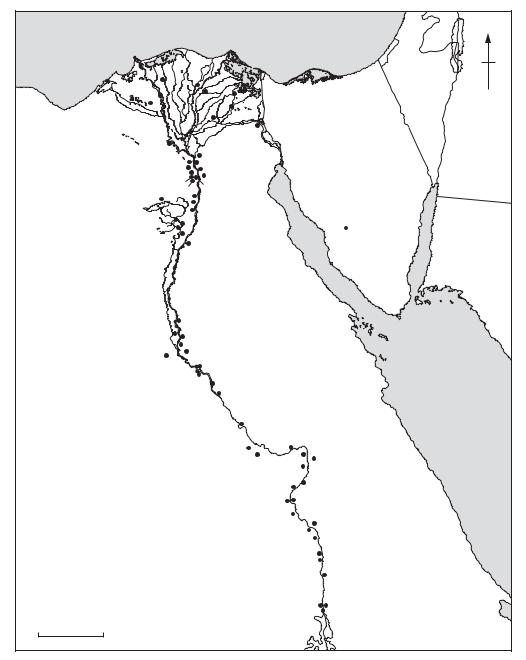

Map 22 |

Egypt Major sites in the region mentioned in the main text or with individual entries in the Dictionary. |

|||||||

214 EGYPT

Neolithic communities had begun to settle along the course of the Nile.

The late Neolithic period in Egypt, generally described as the ‘predynastic’, began in the late 6th millennium BC. A relative chronology for the Upper Egyptian predynastic period (i.e. the AMRATIAN and GERZEAN periods), was first created by Flinders Petrie in the early 1900s (see SERIATION). When Caton-Thompson and Brunton excavated in the el-Badari region (1924–6), they found stratigraphic confirmation of Petrie’s dating system (at Hammamia) and considerable evidence of the earliest Upper Egyptian phase, the Badarian period (see el-BADARI; c.5500-4000 BC). Petrie’s sequence dates 1 to 30 – which he had been careful to leave unallocated – were duly assigned to the various phases of the Badarian. Although radiocarbon and thermoluminescence dates from el-Badari suggest that the period stretched back at least as early as 5500 BC, Brunton’s pre-Badarian – or ‘Tasian’ – phase has been discredited since the 1960s (Hoffman 1979: 142). It has proved somewhat difficult to make direct comparisons between the culture of northern and southern regions of Egypt, since the sites in Upper (southern) Egypt are mainly cemeteries while those in Lower Egypt are mainly settlement remains. Excavations from the 1970s onwards, however, have begun to obtain more information on Upper Egyptian settlements and Delta cemeteries (see van den Brink 1992).

Cemeteries dating to the Amratian phase (also known as Naqada I; c.4000–3500 BC) have been excavated at several sites in Upper Egypt, stretching from Deir Tasa in the north to the Lower Nubian site of Khor Bahan. A rectangular Amratian house has been excavated at Hierakonpolis (Hoffman 1980) and small areas of late Gerzean settlement were excavated at ABYDOS (Peet 1914: 2) and el-Badari (Baumgartel 1970: 484). The earliest Neolithic remains in Lower Egypt are the Faiyum A encampments excavated by Caton-Thompson (1926). The Faiyum A culture was followed by that of MERIMDA BENI SALAMA, the latest phase of which was roughly synchronous with the settlements and cemeteries of EL-OMARI, south of Cairo. The next phase in the Lower Egyptian predynastic is attested at MAðADI, a settlement and cemetery dating from the early to mid-4th millennium BC. Excavations during the 1980s at Minshat Abu Omar and TELL EL-FARAðIN have begun to provide crucial new evidence for the transition to the Early Dynastic period.

T.E. Peet: ‘The year’s work at Abydos’, JEA 1 (1914), 37–39; G. Caton-Thompson: ‘The Neolithic industry of the Northern Faiyum Desert’, JRAI 56 (1926), 309–23;

E.J. Baumgartel: The cultures of prehistoric Egypt, 2 vols (Oxford, 1955–60); W.B. Emery: Archaic Egypt (Harmondsworth, 1961), 30–1; E.J. Baumgartel: Petrie’s Naqada excavation: a supplement (London, 1970); A.J. Arkell: The prehistory of the Nile valley (Leiden, 1975); M.A. Hoffman: Egypt before the pharaohs (New York, 1979); ––––: ‘A rectangular Amratian house from Hierakonpolis’, JNES 39 (1980), 119–37; B.G. Trigger: ‘The rise of Egyptian civilization’, Ancient Egypt: a social history, ed. B.G. Trigger et al. Cambridge, 1983), 1–70; E.C.M. Van den Brink, ed.: The Nile Delta in transition: 4th–3rd millennium BC (Tel Aviv, 1992); B. MidantReynes: The prehistory of Egypt trans. I. Shaw (Oxford, 2000) A.J. Spencer: Early Egypt (London, 1993); K. Bard: ‘The Egyptian predynastic: a review of the evidence’, JFA 21 (1994), 265–88.

2 Pharaonic period. The historical period in Egypt began with the unification of the country into a single state in c.3000 BC, which appears to have coincided with the appearance of many of the accepted components of the state: urbanization, literacy and bureaucracy. Whereas the chronology of the prehistoric and predynastic periods is based primarily on stratigraphy, seriation and radiometric methods of dating, the historical period (usually divided into thirty ‘dynasties’ in accordance with the History compiled by the Egyptian historian Manetho in the 3rd century BC) relies primarily on an elaborate framework of textual evidence.

During the Early Dynastic period (c.3000–2649 BC) the fundamental elements of pharaonic civilization took shape, from the development of the elaborate funerary architecture of the elite to the codification of temple rituals and the evolution of complex systems of taxation and government. The Old Kingdom (c.2649–2150 BC) was characterized archaeologically by the appearance of stone architecture, particularly in the form of royal PYRAMID complexes such as the Step Pyramid of Djoser (c.2620 BC) at SAQQARA and the Great Pyramid of Khufu (c.2540 BC) at GIZA. Only a few traces of Old Kingdom settlements have survived, therefore the evidence for daily life and sociopolitical change derives primarily from religious and funerary contexts. A general decline in royal architecture is observable by the 6th dynasty (c.2323–2150 BC). The proliferation of funerary monuments among the provincial elite of the 6th–8th dynasties has been interpreted as evidence of a gradual decentralization of power, leading to the social instability of the 1st Intermediate Period (c.2150–2040 BC).

At the height of the Middle Kingdom (c.2040–1640 BC) the pharaohs of the 12th dynasty (mostly called Amenemhat or Senusret) reestablished the traditional political hierarchy and