A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdftion, such as EL MIRADOR, Uaxactún and Cerros, date to this interval.

The Classic period is customarily divided into Early (AD 200–600) and Late (AD 600–900) intervals. The Early Classic period is the time of expansion of the STELE cult throughout the lowlands from its apparent centre of development in the region of TIKAL and many sites are ‘named’ in inscriptions by reference to a particular EMBLEM GLYPH. The period is also marked by contacts with TEOTIHUACAN, as evidenced by architectural details (TALUD-TABLERO-style buildings), motifs on buildings and stelae (e.g. images of the rain-god Tlaloc), cylinder tripod pottery and distinctive green obsidian. The end of the Classic period in parts of the southern lowlands, especially near Tikal, is marked by a ‘hiatus’ a perplexing interval of 60 or so years during which very few stelae were erected and elite burials were accompanied by grave goods of lesser quality and quantity.

The Late Classic period is best known in the southern lowlands, where large cities surrounded by dense rural settlement (see Ashmore 1981) covered the landscape. Cities consisted of complexes of stone and masonry buildings, including temple-pyramids and elite residential and administrative structures (such as palaces and acropolises); many of these were decorated with paint, mosaics and stuccoed and modelled reliefs. Other architectural forms found at large lowland centres included courts for playing the BALLGAME, causeways or SACBES joining complexes at the site, and reservoirs. The lowlands were heavily settled during this time, with total population estimates running into the millions. The size and distribution of archaeological sites suggests that population densities might have strained the ability of the agricultural technologies to meet the needs for food. Hieroglyphic texts speak of increased military activity, alliances between sites and frequent battles with the attendant capture of rival kings.

In the southern lowlands, the end of the Classic period is marked by the events of the ‘collapse’, which signalled a dramatic finale to elite culture (see Culbert 1973). Population declined precipitously and early Postclassic remains are found primarily at smaller site centres, in rural areas and around the peripheries of the former Classic core.

The collapse, beginning about AD 800, is marked by the cessation, over a century or longer, of most of the distinctive features of elite culture, such as STELAE, sumptuary burials, monumental construction and polychrome pottery manufacture. Most of the largest centres were also abandoned, leading to the traditional view that the entire southern low-

LOWLAND MAYA 365

lands was devoid of settlement by about AD 1000. Populations did indeed decline dramatically, but in some smaller centres and especially in rural regions occupation continued into Postclassic times. Possible causes of the collapse have been heavily debated and include environmental factors (drought, crop failure, soil exhaustion; see Rice and Rice 1984), disease, internal social disruptions (uprisings, continual elite warfare) and external conflicts. Most archaeologists agree that the collapse was an elite phenomenon and was multi-causal, with different factors operating more or less simultaneously in different places (see COPAN for further discussion of the collapse).

During the period of the collapse, however, the northern lowlands experienced an unparalleled cultural florescence during the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic periods (see Sabloff and Andrews 1986). From about AD 700–1000 the sites of the PUUC region, such as SAYIL and Uxmal, Cobá to the east and also Chichén Itzá in the north-central peninsula, grew and prospered. According to Maya myth and history, Chichén Itzá fell to an alliance between MAYAPAN and Izamal around AD 1200 and its inhabitants fled after the city was sacked.

The Late Postclassic period in the lowlands dates from roughly AD 1200 to the time of European contact/conquest in the early 16th century (although conquest of some remote regions, such as Petén, Guatemala, did not take place until 1697). In the northern lowlands the Late Postclassic period is known from sites such as Tulum, a small port and trading/pilgrimage centre perched on the edge of the peninsula overlooking the Caribbean Sea and MAYAPAN, in the northwest part of the peninsula. The region was integrated politically into a confederacy or ‘league’ of 16 provinces or states, centred in Mayapán.

In the southern lowlands, the Late Postclassic period has been poorly known until recently. Only a few sites, such as Lamanai in Belize and Topoxté in Petén, provide evidence of continuity of occupation from the time of the Classic ‘collapse’ until European contact. At the time of the coming of the Spaniards there was a series of small Maya chiefdoms or kingdoms scattered throughout the area. In central Petén four lineages with separate capitals were integrated by a kind of confederacy centred on Late Petén-Itzá, similar to that of MAYAPAN. However, the antiquity of this arrangement is unknown.

T.P. Culbert, ed.: The classic Maya collapse (Albuquerque, 1973); S. Garza T. and E.B. Kurjack: Atlas arqueológico del estado de Yucatán, 2 vols (Mexico, 1980); W. Ashmore:

Lowland Maya settlement patterns (Albuquerque, 1981);

366 LOWLAND MAYA

R.S. MacNeish: ‘Mesoamerica’, Early man in the New World, ed. R. Shutler, Jr. (Beverly Hills, 1983), 125–35; S.G. Morley, G.W. Brainerd and R.S. Sharer: The ancient Maya, 4th edn (Stanford, 1983); D.S. and P.M. Rice: ‘Lessons from the Maya’, Latin American Research Review

19 (1984), 7–34; J.A. Sabloff and E.W. Andrews V, eds:

Late lowland Maya civilization: classic to postclassic

(Albuquerque, 1986); J.A. Sabloff: The new archaeology and the ancient Maya (New York, 1990).

PRI

Lo-yang (Luoyang) see EASTERN CHOU;

WESTERN CHOU

Lu Ancient Chinese state which was enfeoffed to Po-ch’in, son of Chou-kung, the Duke of Chou, early in the WESTERN CHOU period (c.1115 BC). Its capital was situated in the vicinity of present day CHU’Ü-FU, Shan-tung, China. Chou-kung, brother of Wu-wang, the conqueror of SHANG and first king of the Chou dynasty, was ‘regent’ during the minority of Ch’eng-wang, the second king of Chou. These historical personages have been verified in contemporary and later inscribed bronzes.

Lu was also the home state of Confucius (fl.c.500 BC), whose existence has, however, yet to be archaeologically demonstrated. In the traditional literature, so strongly flavoured with Confucian concepts, there is, not unexpectedly, a wealth of detail but it is often of dubious validity. A vast literature, largely of Western Han and later compilation, has built up around the figure of Confucius. The indirect rôle of Confucian concepts, through the traditional literature, on interpretational matters requires constant review (see CHINA 2). A large number of works on Confucianism have been published by the Committee on Chinese thought (Chicago and Stanford, 1953–62), mainly under the editorship of A.F. Wright.

H.G. Creel: Confucius, the man and the myth (London, 1951); Shigeki Kaizuka: Confucius, trans. G. Bownas (London, 1956); Anon.: Ch’ü-fu Lu-kuo ku-ch’eng [The ancient city of Ch’ü-fu of the state of Lu] Ch’i-nan, 1982).

NB

Luangwa Central African Late Iron Age ceramic tradition found at sites such as Twickenham Road in Zambia. As part of his ‘Two Stream’ hypothesis, David Phillipson thought that the Luangwa Tradition developed north of the Copperbelt out of a Western Stream (i.e. Kalundu) unit similar to the Chondwe culture. According to this scheme, cattlebased societies with Luangwa pottery spread throughout the subcontinent, establishing the

present distribution of Bantu languages. New linguistic research, along with settlement studies and ceramic analyses, have modified this interpretation. Rather than being related to Kalundu (see KALOMO CULTURE), the ceramic style is linked with the Naviundu complex (see DIVUYU), and associated with Western Bantu. At a general level Western Bantu speakers differ from Eastern Bantu in that they trace biological descent through the mother; they also own few, if any, cattle, emphasize brideservice, and traditionally have non-hereditary leaders. The distribution of Luangwa pottery does not extend far south of the Zambezi River, and its patterning reflects the formation of the ‘matrilineal belt’ across Central Africa.

D.W. Phillipson: ‘Iron Age history and archaeology in Zambia’, JAH 15 (1974), 1–25; T.N. Huffman: ‘Ceramics, settlements and Late Iron Age migrations’, AAR 7 (1989), 155–82.

TH

Luba see AFRICA 5.4

Lucy see AUSTRALOPITHECUS; HADAR;

OLDUVAI

Lumbini Religious site located in the Himalayan foothills of Nepal, believed to be the birthplace of the Buddha. The remains include an inscribed sandstone column of the MAURYAN ruler Asoka (273–232 BC), several STUPAS (many now largely destroyed), temples, monastic complexes and an artificial pond enclosed by brick terraces. Evidence of construction at the site ranges in date from the 3rd century BC to the 10th century AD.

D. Mitra: Buddhist monuments (Calcutta, 1971), 58–60; B.L. Pradhan: Lumbini-Kapilwastu-Dewadaha (Kathmandu, 1979).

CS

luminescence dating see

THERMOLUMINESCENCE; OPTICALLY STIMULATED LUMINESCENCE DATING.

Lung-shan (Lungshan) Neolithic culture in China (c.4000–2000 BC), out of which many of the essential aspects of Chinese civilization began to emerge, including the production of wheel-turned pottery and li-style ceramics; the building of hang-t’u structures, walled settlements and large buildings on raised hang-t’u platforms; the emergence of early writing and SCAPULIMANCY (see CHINA 3); an increase in differential burials and

marked variations of mortuary wealth; more efficient kiln design; a greater variety of domesticated animals; the placement of human sacrifices under building foundations; signs of violence indicative of warfare; and evidence for the killing of captives.

The Lung-shan period was once described as the ‘Black Pottery Culture’ and viewed as the successor of the ‘Painted Pottery Culture’ (see YANG-SHAO), thus resulting in a ‘two culture theory’ of the Chinese Neolithic. These earlier interpretations of its significance, however, have undergone appreciable revision since the 1950s. The concept of a ‘Lungshanoid expansion’ was advanced and maintained until the late 1970s, then more or less discarded in favour of a ‘Lungshanoid horizon’ (Chang 1986a: 234). Following the course of archaeological discovery over the ensuing decades, the formulation of ‘spheres of interaction’ is now favoured as a more suitable basis for interpretation of the growing corpus of archaeological data.

In China, however, much of the study of archaeological assemblages may, perhaps, be classed as SERIATION (see CHINA 4). Accordingly, the Lungshan has been compartmentalized into such general regions as the Shan-tung Lung-shan culture, the Middle Yellow River Valley Lung-shan cultures (Eastern, Northern, and Western Ho-nan Lungshan), Shan-hsi Lung-shan, and Shan-hsi Lung-shan, and the related LIANG-CHU, CH’I-CHIA and Ch’ing-lung-ch’üan III cultures. It has also been subdivided into phases, and it is likely that future research will concentrate on the interplay between the different geographical and chronological sections.

In the Shen-hsi and Ho-nan phases of the Lungshan, especially the latter, the earliest signs of metal production appeared, although this evidence is somewhat complicated by the arguments relating to the existence of HSIA and the beginnings of the Shang period (see CHINA 2). Nevertheless, towards the close of the Lung-shan period, the development of metallurgy and writing clearly heralds the rise of civilization in China and the concept of a nuclear area from which influences began to spread centrifugally throughout the ‘barbarian’ peripheral regions.

Chang Kwang-chih: Shang China (New Haven, 1980);

––––: The archaeology of ancient China, 4th edn (New Haven, 1986a); ––––, ed.: Studies of Shang archaeology

(New Haven, 1986b).

NB

LURISTAN 367

Luni industries Middle Palaeolithic stone tool industry first identified by V.N. Misra from surface sites in the Luni River Valley of southern Rajasthan, India. Common tool types include concave and convex scrapers, carinated scrapers, burins, points, handaxes, cleavers and adze blades. Luni artefacts have been found in two main contexts: working floors near ancient lake beds and in association with river gravels. Rhyolite is the most common raw material, but quartzite and quartz were also used.

L.S. Leshnik: ‘Prehistoric explorations in North Gujarat and parts of Rajasthan’, East and West 118 (1968), 295–310; B. Allchin, A. Goudie and K. Hegde: The prehistory and palaeogeography of the Great Indian Desert

(London, 1978), 166–96.

CS

lunulae Crescent-shaped chest ornaments manufactured from sheet gold in the 2nd millennium BC. Lunulae are the most magnificent of a range of beaten and incised goldwork associated with the ‘food vessel’ and BEAKER cultures of the British Isles. Their distribution is concentrated in Ireland, and they were probably hammered out of gold plucked from the streams of western Britain. Many lunulae are decorated with repeated geometric (often triangular) motifs and parallel lines, particularly around their rims and near their terminals. Unlike most contemporary prestige items, lunulae occur mainly as isolated finds and never as burial goods; this suggests they were used as votive offerings, and perhaps also that they were not owned by individuals.

J. Taylor: Bronze Age goldwork of the British Isles

(Cambridge, 1980).

RJA

Luoyang (Lo-yang) see EASTERN CHOU;

WESTERN CHOU

Lupemban industry see SANGOAN

Luristan Mountainous region of western Iran in which a number of early agricultural sites have been excavated, including Tepe Asiab, Tepe Guran, Tepe Giyan and Tepe Sarab. The earliest of these is Asiab, located in the Kermanshah region, where pit-like circular depressions and the surviving bones of goats indicate an early 7th-millennium semi-nomadic herding community living in tents or reed huts. Tepe Guran dates to a slightly later stage in the Neolithic of western Iran; its eight-metre- deep stratigraphy dates from c.6500 to 5500 BC,

368 LURISTAN

showing a gradual transition from an aceramic culture and ephemeral clusters of huts to more permanent Neolithic settlement characterized by pottery and domed ovens which are similar to those excavated at JARMO in Iraq. Tepe Sarab, like Asiab, appears to have been a seasonally occupied settlement; the earliest levels at Sarab are contemporary with the upper strata at Guran, according to calibrated radiocarbon dates ranging from 6006 ± 98 to 5655 ± 96 BC (see Radiocarbon 1963).

Luristan is best known for the unprovenanced ‘bronzes’ that began to appear on the antiquities market in large quantities in 1928–30 (although some examples had already been acquired by the British Museum in the 19th century). These distinctive bronze artefacts, mainly from late Bronze Age and early Iron Age tombs in the Zagros region, include ritual buckets, pinheads, horse-gear, daggers, axes, shields, pole-tops and standards. Some have reliable provenances, such as those excavated at Baba Jan, Kuh-i Dast, Pusht-i Kuh and Surkh Dum (see Vanden Berghe 1971), permitting the formulation of a basic chronology placing them mainly in the first half of the 1st millennium BC (Moorey 1974). In general, however, their interpretation is hampered by the fact that ‘objects deriving from other places are given the fashionable label by dealers’ Frankfort 1970: 340).

There appears to have been a sharp decline in Luristan metalworking after the emergence of the Achaemenian empire in the late 6th century BC, perhaps as a result of the centralization of craftworkers in the vicinity of such cities as Pasargadae and Persepolis (see PERSIA). The debate over the origins and development of the bronzes has centred on the question of whether they can be directly associated with a particular cultural group, such as the KASSITES or the ancestors of the Medes.

The excavations at such seasonally occupied Neolithic sites as Tepe Asiab and Tepe Sarab have been complemented by ethnographic work undertaken by Frank Hole and Sekandar Amanolahi-Baharvand among the modern pastoral nomads of Luristan (Hole 1979). Through a combination of interviews and observation they found that the fundamental differences between the settled agriculturalists and the nomads related to forms of accommodation and quantity of equipment. They also noted that the nomads’ seasonal movements were surprisingly short, wherever possible exploiting regions where summer and winter pastures are only a few kilometres apart. The modern nomads were almost entirely independent of the settlements, leading Hole to suggest that the raising of animal stock in the early Neolithic might

profitably be examined in complete isolation from contemporaneous developments in cereal cultivation.

P. Calmeyer: Datierbare Bronzen aus Luristan und Kirmanshah (Berlin, 1969); H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth, 1970); C.L. Goff: ‘Excavations at Baba Jan, 1968: third preliminary report’, Iran 8 (1970), 141–56; H. Thrane: ‘Tepe Guran and the Luristan bronzes’, Archaeology 23 (1970), 27–35; C.L. Goff: ‘Luristan before the Iron Age’, Iran 9 (1971), 131–52; L. Vanden Berghe: ‘Excavations in Push-i Kuh, tombs provide evidence in dating typical Luristan bronzes’, Archaeology 24 (1971), 263–70; P.R.S. Moorey: Ancient bronzes from Luristan (Oxford, 1974); F. Hole: ‘Rediscovering the past in the present: ethnoarchaeology in Luristan, Iran’, Ethnoarchaeology: implications of ethnography for archaeology, ed. C. Kramer (New York, 1979), 192–218.

IS

Luwians Indo-European-speaking people who appear to have established themselves in southwestern Anatolia by the late 3rd millennium BC; they were perhaps responsible for violent destruction levels in settlements such as Alaça Hüyük and Hisarlik. It has been suggested that these invaders in fact constituted the earliest wave of ‘HITTITES’ (in the broadest sense of the term). The Luwian language at least seems to have survived well into the neo-Hittite phase (early 1st millennium BC), when one of its dialects was transcribed into the so-called Hittite hieroglyphs.

J.D. Hawkins: ‘Some historical problems of the hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions’, AS 29 (1979), 153–67.

IS

Luxor Theban religious site dedicated to the cult of the fertility god, Amun Kamutef. Known as the ipet resyt (‘southern harem’), the first major parts of Luxor temple were constructed in the reign of Amenhotep III (c.1391–1353 BC) and it was augmented by successive pharaohs (including Ramesses II and Alexander the Great). It was constructed largely as a suitable architectural setting for the culmination of the Festival of Opet, which comprised a ritual procession of divine images from KARNAK. The main purpose of this festival was to allow the reigning king annually to reinforce his power by uniting with his royal ka (spiritual essence or double) in the temple sanctuary. It was transformed into a shrine of the imperial cult in the Roman period and eventually partially overbuilt by the mosque of Abu Haggag. In 1989 a cachette of exquisitely carved and well-preserved 18th-dynasty

stone statuary was excavated from beneath the floor of the court of Amenhotep III.

A. Gayet: Le temple de Louxor (Cairo, 1894); L. Bell, ‘Luxor temple and the cult of the royal ka’, JNES 44 (1985), 251–94; M. El-Saghir, The discovery of the statuary cachette of Luxor temple (Mainz, 1991).

IS

L’yalova culture see PIT-AND-COMB

Lydenburg (Heads site) Village site of the Early Iron Age just east of the town of Lydenburg in the eastern Transvaal, South Africa. The site, on sloping ground above a small stream, is heavily eroded, and the only structural features so far revealed by excavation are a dozen shallow pits containing variable quantities of bone, iron slag, charcoal, pottery, stone, and daga (puddled clay) from pole and daga huts. The most notable finds are the remains of seven terracotta heads, unique in the Early Iron Age of eastern and southern Africa (although a fragment, unassociated, has been

LYNCHET 369

recorded 50 km to the east). Small finds include beads of iron, copper, and shell, and pieces of worked bone and ivory. The site is securely dated to the early 6th century AD. Opinion is divided as to whether the ceramics owe their origin to movements from the north, or from the east coast.

R.R. Inskeep and T.M. Maggs: ‘Unique art objects in the Iron Age of the Transvaal’, SAAB, 30 (1975), 114–38; T.M. Evers: ‘Excavations at the Lydenburg heads site, eastern Transvaal, South Africa’, SAAB 37 (1982), 16–33.

RI

lynchet (‘cultivation terrace’) ‘Positive lynchets’ are formed by the build up of slopewash deposits along the edge of field boundaries as a result of ploughing. Erosion on the downslope side of the boundary creates ‘negative lynchets’. They are well documented in the so-called CELTIC FIELDS, while long strip lynchets are characteristic of post-Roman agriculture.

Ordnance Survey: Field archaeology in Great Britain

(Southampton, 1973), 141.

PTN

M

Maðadi Late predynastic/protodynastic settlement and cemeteries located about 5 km south of Cairo, dating to c.3600–2900 BC. Maðadi is the typesite of the final culture in the Lower Egyptian predynastic sequence, roughly equivalent to the late Gerzean (Naqada III) phases at such Upper Egyptian sites at HIERAKONPOLIS and ABYDOS (see EGYPT: PREHISTORIC). The settlement at Maðadi, consisting mainly of wattle and daub oval huts, is thought to have acted as an important entrepôt, controlling trade between Upper Egypt and the Levant and probably also exploiting the copper reserves of the Sinai peninsula (Rizkana and Seeher 1984). Cemetery South at Maðadi is the earliest of the three cemeteries, and the 468 graves shallow round pits sometimes covered with rough stone blocks – are among the first Lower Egyptian funerary contexts to show pronounced variations in quality of funerary equipment, thus suggesting the appearance of social stratification.

M. Amer: ‘Annual report of the Maadi excavations, 1935’, CdE 11 (1936), 54–7; M.A. Hoffman: Egypt after the pharaohs (New York, 1979), 200–14; I. Rizkana and J. Seeher: ‘New light on the relation of Maadi to the Upper Egyptian cultural sequence’, MDAIK 40 (1984), 237–52;

––––: Maadi, 4 vols (Mainz, 1987–90).

IS

Mabveni Earliest cultural ‘package’ of the Central African Early Iron Age (EIA), dating to the 2nd–6th centuries AD. Mabveni was the first site

to show that EIA |

people were |

newcomers |

with a new way of |

life and set |

of beliefs. |

Keith Robinson uncovered raised grain-bin supports, an underground storage pit, remains of domestic cattle, sheep/goat teeth, metal slag and characteristic pottery of the Gokomere facies of NKOPE. The pottery differs somewhat from that of Ziwa, the next Nkope facies to the north, and this may be due to a merge with an earlier Kulundu Tradition occupation such as

BAMBATA.

K.R. Robinson: ‘An early Iron Age site from the Chibi District, southern Rhodesia’, SAAB 16 (1961), 75–102;

T.N. Huffman: ‘Cattle from Mabveni’, SAAB 30 (1975), 23–4.

TH

Macassans Sailors from the southern Celebes port of Macassar in present-day Indonesia, who visited northern Australia to collect and process bêche-de-mer (sea-cucumber). These visits may date back over a thousand years.

C.C. Macknight: The voyage to Marege (Melbourne, 1976).

CG

Ma-chia-pang (Majiabang) see HO-MU-TU;

LIANG-CHU; YANG-SHAO

Machu Picchu The fabled ‘lost city’ of the INCA

– located in the Urubamba Valley, Peru – was in reality the country residence of Pachacuti Inca Yupanki, the founder of the Inca empire. It is remarkable for its preservation, for the numbers of shrines and religious edifices (Pachacuti was extremely interested in religious matters, having founded the state religion), and for its setting in a precipitous, forest-covered landscape with views of various snow-capped (and hence sacred) mountains. In modern times, Machu Picchu and related ruins are in danger because of their popularity with tourists.

H. Bingham: Machu Picchu, a citadel of the Incas: report of the explorations and excavations made in 1911, 1912, and 1915 under the auspices of Yale University and the National Geographic Society (Oxford, 1930); L. Meisch: ‘Machu Picchu: conserving an Inca treasure’, Archaeology 38/6 (1986), 18–25; J.H. Rowe: ‘Machu Picchu a la luz de documentos del siglo XVI’, Histórica 14/1 (1990), 139–45.

KB

Macon Plateau see OCMULGEE

Madrague de Giens Site near Toulon in southern France where a Roman wreck of

c.70–50 BC was discovered in 1967 at a depth of 18 m. It was excavated in 1971–83 by Patrice Pomey and André Tchernia. The main cargo consisted of wine stored in about 6000–7000 amphorae, with a filled weight of some 350–400 tonnes; there were also consignments of blackgloss table ware and red coarseware. The forty-metre hull was magnificently preserved, and is a fine example of shell-first mortise- and-tenon construction (see MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY). The excavation at Madrague de Giens has improved understanding of exchange mechanisms in pre-conquest Gaul, the economic behaviour of the Roman elite, and the organization of wine production. Alongside luxury commerce, the coarseware is one of many instances of wrecks providing evidence on long-distance trade in mundane, utilitarian goods, a possibility previously denied by primitivist models of the ancient economy.

A. Tchernia, P. Pomey and A. Hesnard: L’épave romaine de la Madrague de Giens (Paris, 1978); A. Tchernia: Le vin de l’Italie Romaine (Paris, 1986); A.J. Parker: ‘The wines of Roman Italy’, Journal of Roman Archaeology 3 (1990), 325–31; ––––: Ancient shipwrecks of the Mediterranean and the Roman provinces (Oxford, 1992), 249–50.

DG

Maes Howe Neolithic PASSAGE GRAVE on

Mainland in the Orkney Islands, Scotland – one of the most finely built examples of the chamber tomb tradition. Constructed in about 2750 BC, it consists of a passage 12 m long, lined with huge but thin megaliths and built in two sections of different height, leading into a vaulted chamber of about 4.5 metres square. This chamber has small square cells set into three of its walls above the floor-level, internal buttresses in each of the corners, and a corbelled roof. The impression given by the interior is almost ‘architectural’ – the builders have used the thin and regularly fractured local slabs of flagstone to great symmetrical effect. The chamber is surrounded by a stepped stone cairn, heaped over with earth and rubble to form a round mound, the whole now measuring about 35 m in diameter and 7.3 m high. The tomb was excavated by Gordon Childe (1954–5) and Colin Renfrew (1973–4), but the chamber had been largely empty for centuries: runic inscriptions on the chamber walls reveal that the tomb was entered during the medieval period by Vikings.

V.G. Childe: ‘Maes Howe’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 88 (1954–6); C. Renfrew:

Investigations in Orkney, Society of Antiquaries of London

MAGHZALYA, TELL 371

Research Report 38 (London, 1979); ––––, ed.: The prehistory of Orkney (Edinburgh, 1985).

RJA

Magan see UMM AN-NAR

Magdalenian Final industry of the Upper Palaeolithic of Western Europe, centred on southwest France and northern Spain in the period between about 15,000 and 10,000 BC. The Magdalenian, named after the type-site of La Madeleine, is traditionally divided into Magdalenian I–VI (Breuil 1912) by means of the typology of the rich bone, ivory and antler industry (including spearthrowers, harpoons and BÂTONS PERCÉ (i.e. bâtons-de-commandement); this series has been extended backwards to include the primitive ‘Magdalenian 0’ uncovered at LAUGERIE HAUTE. However, the validity of the series is now doubted, and Abbé Breuil’s strict evolutionary sequence from the various bone points and bâtons of the Lower Magdalenian (I–III) through to the increasingly complex prototype, single-row and double-row harpoons of the Upper Magdalenian (Magdalenian IV–VI) has largely been abandoned. The bone typology has never been satisfactorily tied to a stone tool typology; indeed Laville et al. (1980: 295) suggest that Magdalenian stone assemblages are best divided simply in two, equating with Magdalenian 0–I and Magdalenian II–VI. In this scheme, the earliest lithic assemblage is characterized by certain AURIGNACIAN traits (e.g. carinate scrapers) and later by raclettes. The later assemblage is rich in burins and backed bladelets.

Although the classic Magdalenian is concentrated around southern France and northern Spain, certain features of the complex are present in other parts of western Europe (Britain, Germany) and in Poland; Praslov et al. (1989) cite assemblages from Russia (e.g. Yudinovo on the Sudost River) that seem related to the Magdalenian lithic assemblages.

H. Breuil: Les subdivisions du Paléolithique supérieur et leur signification, Comptes Rendus de 14e Congrès International d’Antropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistorique (Geneve, 1912); H. Laville et al.: Rockshelters of the Perigord (New York, 1980); N.D. Praslov et al.: ‘The steppes in the late Palaeolithic’, Antiquity 63 (1989), 784–92.

RJA

Maghzalya, Tell Aceramic Neolithic settlement site on the Sinjar plain to the west of Mosul in northwestern Iraq. The village covered one hectare and, with its curving buttressed enclosure wall, is

372 MAGHZALYA, TELL

the earliest known fortified settlement in Mesopotamia. An area of about 4,500 sq. m was excavated by Soviet archaeologists in 1977–80, revealing a series of rectangular clay houses with stone-built foundations and stone-paved, plastered floors. The 15 occupation strata contained flint arrowheads and obsidian sickle blades, as well as stone rubbing stones, querns and pestles. The presence of wild and domesticated barley and emmer wheat, alongside faunal remains suggesting the hunting of wild bulls, indicates that the assemblage at Maghzalya was essentially characteristic of the ‘Jarmoan’ culture (c.7000–6000 BC; see JARMO). The site has been compared with ACERAMIC NEOLITHIC (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) settlements in Syria and Anatolia, such

as TELL ABU HUREYRA, ÇAYÖNÜ TEPESI and

MUREYBET (Merpert et al. 1981: 62).

N.Y. Merpert, R.M. Munchaev and N.O. Bader: ‘Investigations of the Soviet expedition in northern Iraq, 1976’, Sumer 37 (1981), 22–54; N. Yoffee and J.J. Clark, ed.: Early stages in the evolution of Mesopotamian civilization: Soviet excavations in northern Iraq (Tucson, 1993).

IS

Maglemosian (Maglemosean) Widespread family of early Mesolithic industries, extending from Britain across the North European Plain, defined in the Magle Mose bogland area of Zealand, Holland. The lithic industry is characterized by the presence of axes obliquely blunted points and flints in the shape of large isoceles triangles. The presence of microliths (tiny worked flints) and axes (presumed to represent evidence of increased wood-working in the more thickly forested Holocene environment) differentiate the assemblages from those of the Upper Palaeolithic.

The Maglemosian is often contrasted with the other two main assemblage types of the Meso-

lithic, the SAUVETERRIAN and the TARDENOISIAN.

However, the exact distribution of the Maglemosian really depends on how loosely or tightly the characteristics of the industry are defined – modern researchers tend to stress that variation between assemblages can arise from different environmental contexts and different preservation as much as from ‘cultural’ differences. It is now felt unwise, for example, to assume that the sites of northern Britain with ‘Maglemosian’ characteristics (most famously, STAR CARR) are culturally distinct from the non-Maglemosian lowland sites. Rowley-Conwy suggests that rather than debating how to assign each site, it might be better to break the Mesolithic of France, the United Kingdom and the North European Plain into the

following broad chronological scheme (1) broadblade assemblages with obliquely blunted points (roughly equivalent to the Maglemosian) (2) narrow-blade assemblages with a more varied range of microlith shape, especially in the scalene triangle shape (this phase seems to originate in southern France) (3) blade and trapeze industries across Europe, but not the United Kingdom.

S.K. Kozłowski, ed.: The Mesolithic in Europe (Warsaw, 1973); P. Rowley-Conwy: ‘Between cavepainters and crop planters: aspects of the temperate European Mesolithic’ Hunters in transition, ed. M. Zvelebil (Cambridge, 1986), 17–29.

RJA

magnetic survey Common geophysical survey technique that makes use of a magnetometer to measure minor fluctuations in the earth’s magnetic field at specific points on an archaeological site. Anomalies in the magnetic field suggest that the underlying area has been disturbed in some way, possibly by ancient buried structures. In particular, magnetic surveys can be helpful in locating rubbishfilled ditches and pits, kilns, hearths, and features lined with fired clay. Like the other main geophysical survey technique, the soil RESISTIVITY SURVEY, magnetometer surveys are a form of relative measurement and the results have to be carefully interpreted. Unlike resistivity surveys, they are not affected by the amount of moisture retained in the soil, but care has to be taken to allow for natural fluctuations in the earth’s magnetic field and, sometimes, to make sure that metal objects that may affect the results are removed from the surface of the site before the survey. Furthermore, many natural features and modern features also produce magnetic anomalies. Typically, the survey procedure might involve taking readings at one metre intervals across a grid laid out over the site using the most common type of magnetometer, a proton magnetometer. After correcting the readings for any general fluctuations in the magnetic field during the course of the survey, the data can be plotted out to reveal features of potential interest.

A. Clark: Seeing beneath the soil: prospecting methods in archaeology (London, 1990).

RJA

magnetometer see ARCHAEOMAGNETIC DATING; MAGNETIC SURVEY

Magosi, Magosian Stone Age rock-shelter located beside natural cisterns in a dry part of northeastern Uganda, which was once thought to

illustrate the ‘intermediate’ stage between the African Middle and Late Stone Ages, that is essentially the transition from LEVALLOIS flake industries towards a microlithic one (‘WILTON’ type), around the end of the Pleistocene. Such conclusions were based on E.J. Wayland’s excavations in the 1920s. Re-examination in the 1960s (Posnansky and Cole 1963) indicated that much of the supposedly ‘transitional’ materials in the Magosi stratigraphy resulted from mixing of those from higher and lower levels. ‘Magosian’ levels elsewhere (notably at APIS ROCK in Tanzania) have been similarly reinterpreted, just as the concept of a linear progression of stone-age cultures defined by tool types and lithic technology has become less fashionable.

M. Posnansky and G.H. Cole: ‘Recent excavations at Magosi, Uganda’, Man (O.S.) 1963 [article no.133].

JS

Maiden Castle see HILLFORT

Maikop Famously rich series of Bronze Age burial mounds (kurgans), located in the North Caucasus (Russia) and discovered and excavated in 1897 by N.I. Veselovsky. The largest of the mounds was 11 m high; burial chambers contained pottery, metal tools and ornaments, and two golden and 14 silver vessels. Among the remarkable finds were gold figurines of bulls and lions, originally sewn onto garments; gold and silver bull-figurines adorning canopies; gold beads and rings; gold, silver, turquoise and carnelian beads; copper axes, tanged axes and spearheads. Some of these prestige items were of Middle Eastern origin.

MAJIABANG 373

By comparing the Maikop finds to similar assemblages from a number of sites, Russian archaeologists (Iessen 1950; Munchaev 1970) have identified a ‘Maikopian culture’, which is concentrated in the northwestern Caucasus, but which influenced the northeastern Caucasus and Transcaucasia. A.A. Iessen (1963) has distinguished two stages in the development of the Maikopian tradition: the Maikop proper and the Novosvobodnaya. The former is characterized by large rectangular burial chambers beneath kurgans, while the Novosvobodnaya-type kurgans contained dolmens. Iessen (1950) dates the Maikop culture to the middle/second half of the 3rd millennium BC, while a more recent series of radiocarbon measurements for the Ust’-Jegutinsky cemetery, near the town of Cherkessk, suggest calendar dates of c.2500–2400 BC. However, the detailed chronology of the culture, and its relationships with the (broadly contemporary) north-Caucasian variant of and the KURA-ARAXIAN in Transcaucasia, remain unclear.

A.A. Iessen: ‘Khronologii bol’ših kubanskih kurganov’ [The chronology of the Great Kuban kurgans], Sovetskaja arheologija 12 (1950), 157–202; ––––: ‘Kavkaz i Drevnii Vostok v IV–III tysjacˇeletii do n.e.’ [The Caucasus and the Ancient East in the 4th–3rd millennium BC], KSIA 93 (1963), 3–14; R.M. Munchaev: Kavkaz na zare bronzovogo veka [The Caucasus on the eve of the Bronze Age] (Moscow, 1970).

PD

Majiabang see MA-CHIA-PANG

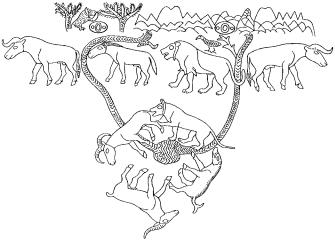

Figure 29 Maikop Early ‘landscape’ design incised on a silver bowl of the 3rd millennium BC found at Maikop (now in the Hermitage, St Petersburg). Source: H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth: Pelican, 1970), fig. 243.

374 MAKAPANSGAT

Makapansgat Oldest of the South African sites that have yielded remains of AUSTRALOPITHECUS located in the ancient Limeworks cavern system, containing bone-rich breccia, ten

miles east–northeast of Potgietersrus, central Transvaal, South Africa. On faunal grounds the site is thought to be around three million years old. Raymond Dart’s osteodontokeratic (bone, tooth and horn) ‘culture’ proposed on the basis of finds from this site is now explained in terms of the natural factors affecting bone accumulation and preservation in ancient limestone caverns.

C.K. Brain: The Transvaal ape-man-bearing cave deposits

(Pretoria, 1958); J.M. Maguire: ‘Recent geological, stratigraphic and palaeontological studies at Makapansgat Limeworks’, Hominid evolution: past, present and future, ed. P.V. Tobias (New York, 1985).

RI

Makouria see NUBIA

Malatya (Arslantepe; anc. Melitene) The modern Turkish town of Malatya is built over the ruins of a Hellenistic/Roman town but the adjacent tellmound of Arslantepe dates back to the Bronze Age and early Iron Age. This earlier settlement flourished during the late Hittite and Syro-Hittite periods (c.1300–700 BC), but there are also strata dating back to the 4th millennium BC, which contain ceramic material comparable with URUK and TEPE GAWRA, as well as numerical tablets and Uruk-style CYLINDER SEALS, suggesting that the Sumerians had established extensive trading links as far north as the Anatolian plateau.

L. Delaporte: Malatya Arslantepe (Paris, 1940); S.M. Puglisi and P. Meriggi: Malatya I (Rome, 1964).

IS

Malkata Egyptian settlement and palace site of the early 14th century BC, situated at the southern end of western Thebes, opposite modern Luxor, which was excavated in 1888–1918 (Tytus 1903; Hayes 1951) and the early 1970s (Kemp and O’Connor 1974). It comprises several large official buildings (including four probable palaces) built by the 18th-dynasty ruler Amenhotep III (c.1391–1353 BC), as well as kitchens, store-rooms, residential areas and a temple dedicated to the god Amun. To the east of Malkata are the remains of a large artificial lake evidently created at the same time as Amenhotep III’s palaces (Kemp and O’Connor 1974).

R. de P. Tytus: A preliminary report on the pre-excavation of the palace of Amenhotep III (New York, 1903); W.

Hayes: ‘Inscriptions from the palace of Amenophis III’, JNES 10 (1951), 35–40; B.J. Kemp and D. O’Connor: ‘An ancient Nile harbour: University Museum excavations at the Birket Habu’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 3/1 (1974), 101–36.

IS

Maltai see ASSYRIA

Maltese temples Group of around 24 architecturally similar ritual buildings erected on the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Gozo c.3500–2500 BC, representing some of the earliest sophisticated stone architecture in the world. The islands’ first inhabitants, who may have arrived from Sicily in the 5th millennium BC, built simple stone and mud-brick ritual structures, exemplified by a small oval-roomed ‘shrine’ at Skorba. These structures, together with rock-cut tombs created in the 4th millennium BC, provide possible antecedents for the temples. Even so, the temples were a precocious development, unparalleled elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Their typological evolution remains unclear, but the most complicated designs appear to be elaborations of an early ‘three-leaf clover’ shaped groundplan (e.g. Ggantija South). Nearly all the temples have monumental concave facades, in front of which rituals were probably performed; the later examples are built entirely of large, well-tooled blocks. Trilithons form imposing temple entrances and the upper courses of walls are

A B C

D

F E

Figure 30 Maltese temples The evolution of the ‘Maltese temples’: (A) a rock-cut tomb, Xemxija, (B) lobed temple, Mgarr East, (C) trefoil temple, with later cross-wall, Skorba West, (D) 5-apse temple, Ggantija South, (E) 4-apse temple, Mnajdra Central, (F) 6-apse temple, Tarxien Central; the scale measures 3 m. Source: D. Trump: ‘Megalithic architecture in Malta’, The megalithic monuments of western Europe, ed. C. Renfrew (London, 1981), p. 65.