- •Contents

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •About the Authors

- •How to Use Herbal Medicines

- •Introduction

- •General References

- •Agnus Castus

- •Agrimony

- •Alfalfa

- •Aloe Vera

- •Aloes

- •Angelica

- •Aniseed

- •Apricot

- •Arnica

- •Artichoke

- •Asafoetida

- •Avens

- •Bayberry

- •Bilberry

- •Bloodroot

- •Blue Flag

- •Bogbean

- •Boldo

- •Boneset

- •Borage

- •Broom

- •Buchu

- •Burdock

- •Burnet

- •Butterbur

- •Calamus

- •Calendula

- •Capsicum

- •Cascara

- •Cassia

- •Cat’s Claw

- •Celandine, Greater

- •Celery

- •Centaury

- •Cereus

- •Chamomile, German

- •Chamomile, Roman

- •Chaparral

- •Cinnamon

- •Clivers

- •Clove

- •Cohosh, Black

- •Cohosh, Blue

- •Cola

- •Coltsfoot

- •Comfrey

- •Corn Silk

- •Couchgrass

- •Cowslip

- •Cranberry

- •Damiana

- •Dandelion

- •Devil’s Claw

- •Drosera

- •Echinacea

- •Elder

- •Elecampane

- •Ephedra

- •Eucalyptus

- •Euphorbia

- •Evening Primrose

- •Eyebright

- •False Unicorn

- •Fenugreek

- •Feverfew

- •Figwort

- •Frangula

- •Fucus

- •Fumitory

- •Garlic

- •Gentian

- •Ginger

- •Ginkgo

- •Ginseng, Eleutherococcus

- •Ginseng, Panax

- •Golden Seal

- •Gravel Root

- •Ground Ivy

- •Guaiacum

- •Hawthorn

- •Holy Thistle

- •Hops

- •Horehound, Black

- •Horehound, White

- •Horse-chestnut

- •Horseradish

- •Hydrangea

- •Hydrocotyle

- •Ispaghula

- •Jamaica Dogwood

- •Java Tea

- •Juniper

- •Kava

- •Lady’s Slipper

- •Lemon Verbena

- •Liferoot

- •Lime Flower

- •Liquorice

- •Lobelia

- •Marshmallow

- •Meadowsweet

- •Melissa

- •Milk Thistle

- •Mistletoe

- •Motherwort

- •Myrrh

- •Nettle

- •Parsley

- •Parsley Piert

- •Passionflower

- •Pennyroyal

- •Pilewort

- •Plantain

- •Pleurisy Root

- •Pokeroot

- •Poplar

- •Prickly Ash, Northern

- •Prickly Ash, Southern

- •Pulsatilla

- •Quassia

- •Queen’s Delight

- •Raspberry

- •Red Clover

- •Rhodiola

- •Rhubarb

- •Rosemary

- •Sage

- •Sarsaparilla

- •Sassafras

- •Saw Palmetto

- •Scullcap

- •Senega

- •Senna

- •Shepherd’s Purse

- •Skunk Cabbage

- •Slippery Elm

- •Squill

- •St John’s Wort

- •Stone Root

- •Tansy

- •Thyme

- •Uva-Ursi

- •Valerian

- •Vervain

- •Wild Carrot

- •Wild Lettuce

- •Willow

- •Witch Hazel

- •Yarrow

- •Yellow Dock

- •Yucca

- •1 Potential Drug–Herb Interactions

- •4 Preparations Directory

- •5 Suppliers Directory

- •Index

Valerian

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

The traditional use of valerian as a mild sedative and hypnotic is supported by evidence from preclinical and some clinical studies. Clinical trials, however, have been heterogeneous in their design, outcomes, and products assessed, such that the evidence for the hypnotic and sedative effects of valerian root is inconclusive when considered collectively or for individual preparations. The chemistry of valerian root is welldocumented. The sedative activity of valerian has been attributed to both the volatile oil and iridoid valepotriate fractions, but it is still unclear whether other constituents in valerian represent the active components. The valepotriate compounds are highly unstable and, therefore, are unlikely to be present in significant concentrations in finished products and probably degrade when taken orally. In view of this, the clinical significance of both the sedative and cytotoxic/ mutagenic activities of valepotriates documented in vitro is unclear.

There are only limited data on safety aspects of valerian preparations from clinical trials. Randomised, placebocontrolled trials involving healthy volunteers or patients with diagnosed insomnia indicate that adverse events with valerian are mild and transient. Post-marketing surveillance-type studies are required to establish the safety of valerian preparations, particularly with long-term use. Some studies suggest that valerian may have a more favourable tolerability profile than certain benzodiazepines, particularly in view of its apparent lack of ’hangover’ effects, although this requires further investigation.

Intake of valerian preparations immediately (up to two hours) before driving or operating machinery is not recommended. Excessive consumption of alcohol whilst receiving treatment with valerian root preparations should be avoided. Patients should seek medical advice if symptoms worsen beyond two weeks’ continuous treatment with valerian. Patients with known sensitivity to valerian should not use valerian root preparations. The potential for preparations of valerian to interfere with other medicines administered concurrently, particularly those with similar (such as barbiturates and other sedatives) or opposing effects, should be considered.

There are isolated reports of adverse effects, mainly hepatotoxic reactions, associated with the use of singleingredient and combination valerian-containing products.

VHowever, causal relationships for these reports could not be established as other factors could have been responsible for the observed effects.

Species (Family)

Valeriana officinalis L. (Valerianaceae)

Synonym(s)

All-Heal, Belgian Valerian, Common Valerian, Fragrant Valerian,

Garden Valerian

Part(s) Used

Rhizome, root

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

American Herbal Pharmacopoeia(1, G1) BHC 1992(G6)

BHP 1996(G9) BHMA 2003(G66) BP 2007(G84)

Complete German Commission E(G3)

EMEA HMPC Community Herbal Monograph(G80) ESCOP 2003(G76)

Martindale 35th edition(G85) Ph Eur 2007(G81) USP29/NF24(G86)

WHO volume 1 1999(G63)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL(G37)

Constituents

See also References 1–5.

Alkaloids Pyridine type. Actinidine, chatinine, skyanthine, valerianine and valerine.

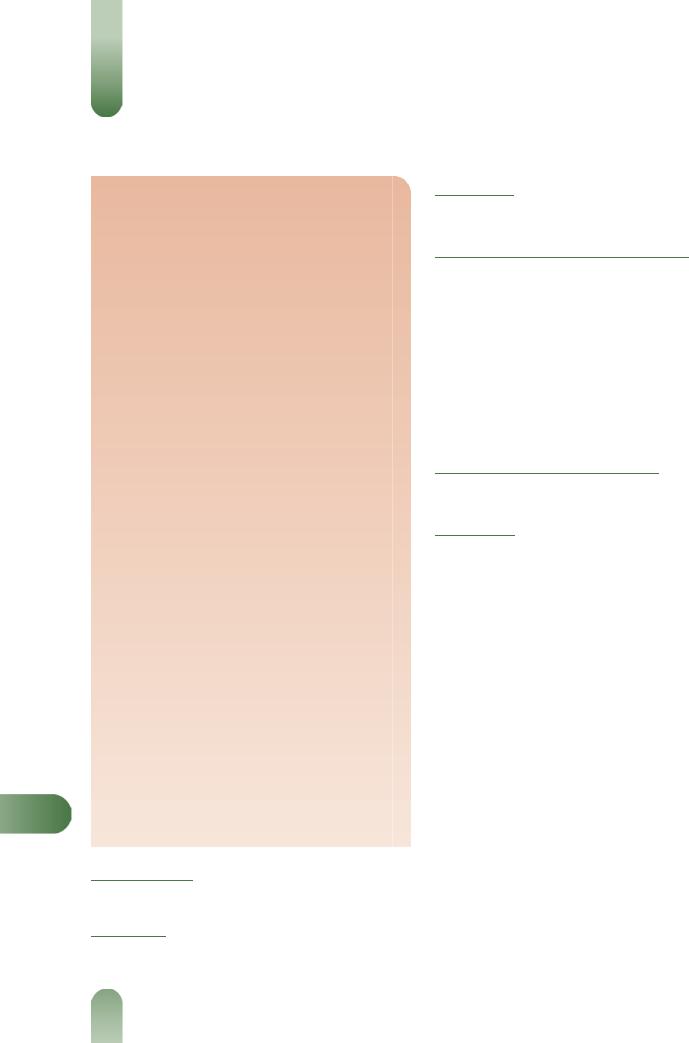

Iridoids (valepotriates) Valtrates (e.g. valtrate, valtrate isovaleroxyhydrin, acevaltrate, valechlorine), didrovaltrates (e.g. didrovaltrate, homodidrovaltrate, deoxydidrovaltrate, homodeoxydidrovaltrate, isovaleroxyhydroxydidrovaltrate) and isovaltrates (e.g. isovaltrate, 7-epideacetylisovaltrate). Valtrate and didrovaltrate are documented as the major components. Valerosidate (iridoid glucoside).(6) The valepotriates are unstable and decompose on storage or processing; the main degradation products are baldrinal and homobaldrinal. The baldrinals may react further and are unlikely to be present in finished products.

Steroids b-sitosterol, clionasterol 3-b-O-glucoside and a mixture of 60-O-acyl-b-D-glucosyl clionasterols where the acyl moieties are hexadecanoyl (major), 8E,11E-octadecadienoyl and 14-methyl- pentadecanoyl.(7)

Volatile oils 0.5–2%. Numerous identified components include monoterpenes (e.g. a- and b-pinene, camphene, borneol, eugenol, isoeugenol) present mainly as esters, sesquiterpenes (e.g. b- bisabolene, caryophyllene, valeranone, ledol, pacifigorgiol, patchouli alcohol, valerianol, valerenol and a series of valerenyl esters,

valerenal, valerenic acid with acetoxy and hydroxy derivatives).(8–

11)

Other constituents Amino acids (e.g. arginine, g-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamine, tyrosine),(1, 12) caffeic and chlorogenic acids (polyphenolic), methyl 2-pyrrolketone, choline, tannins (type unspecified), gum and resin.

580

Valerian 581

Figure 1 Selected constituents of valerian.

Quality of plant material and commercial products

According to the British and European Pharmacopoeias, valerian consists of the dried underground parts of V. officinalis L.,

including the rhizome surrounded by the roots and stolons.(G81, G84) It contains not less than 5 mL/kg of essential oil for the whole

drug and not less than 3 mL/kg for the cut drug, both calculated with reference to the dried drug, and not less than 0.17% of

sesquiterpenic acids expressed as valerenic acid, calculated with reference to the dried drug.(G81) As with other plants, there can be

variation in the content of active compounds (e.g. valerenic acid derivatives and valepotriates) found in valerian rhizomes and roots.(13) Detailed descriptions of V. officinalis root for use in botanical, microscopic and macroscopic identification have been published, along with qualitative and quantitative methods for the assessment of V. officinalis root raw material.(1, G1)

Food Use

Valerian is not generally used as a food. Valerian is listed by the

Council of Europe as a natural source of food flavouring (root: category 5) (see Appendix 3, Table 1).(G17) Previously, valerian has

been listed as GRAS (Generally Recognised As Safe).

Herbal Use

tionally, it has been used for hysterical states, excitability, insomnia, hypochondriasis, migraine, cramp, intestinal colic, rheumatic pains, dysmenorrhoea, and specifically for conditions presenting nervous excitability.(G2, G6, G7, G8, G32, G64) Modern interest in valerian is focused on its use as a sedative and hypnotic.

A Community Herbal Monograph adopted by the European Medicines Agency's Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products states the following therapeutic indications for valerian root:

V

Valerian is stated to possess sedative, mild anodyne, hypnotic, |

|

antispasmodic, carminative and hypotensive properties. Tradi- |

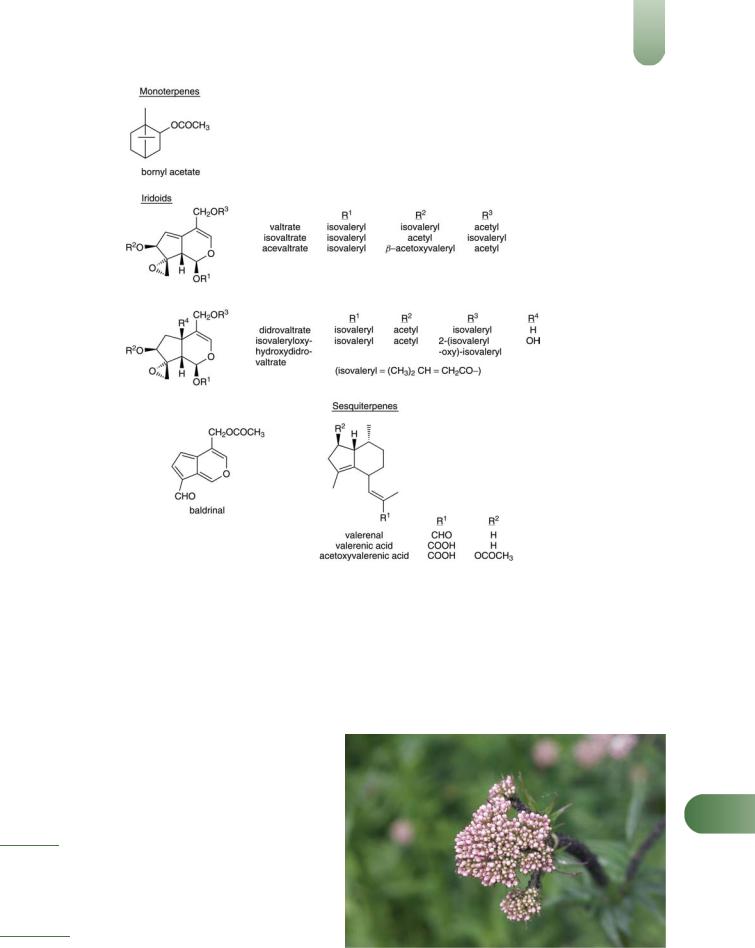

Figure 2 Valerian (Valeriana officinalis). |

582 Valerian

Figure 3 Valerian – dried drug substance (rhizome).

traditional use, for support of mental relaxation and to aid natural sleep; well-established use, for the relief of mild nervous tension and difficulty in falling asleep.(G80)

Dosage

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses recommended in standard herbal reference texts are given below.

Dried rhizome/root 1–3 g as an infusion or decoction up to three times daily.(G6)

Tincture 3–5 mL (1 : 5; 70% ethanol) up to three times daily;(G6, G50) 1–3 mL, once to several times daily.(G3)

Extracts Amount equivalent to 2–3 g drug, once to several times daily;(G3) 2–6 mL of 1 : 2 liquid extract daily.(G50)

Doses given in older texts vary. For example: Valerian Liquid Extract (BPC 1963) 0.3–1.0 mL; Simple Tincture of Valerian (BPC 1949) 4–8 mL; Concentrated Valerian Infusion (BPC 1963) 2– 4 mL.

Clinical trials investigating the effects of valerian root extracts on sleep parameters have used varying dosages, for example,

valerian extract 400 mg/day (drug to extract ratio of 3 : 1)(14) and 1215 mg/day (drug to extract ratio of 5 to 6 : 1).(15)

Pharmacological Actions

Sedative and hypnotic properties have been described for certain valerian rhizome/root preparations following preclinical and clinical studies. However, the available scientific evidence is strong; also it remains unclear precisely which of the constituents of valerian are responsible for the observed sedative and hypnotic properties.(5) Attention had focused on the volatile oil, and then

Vthe valepotriates and their degradation products, as the constituents responsible. However, it appeared that the effects of the volatile oil could not account for the whole action of the drug, and the valepotriates, which degrade rapidly, are unlikely to be present in finished products in significant concentrations. Current thinking is that the overall effect of valerian is due to several different groups of constituents and their varying mechanisms of action. Therefore, the activity of different valerian preparations

will depend on their content and concentrations of several types of constituent.(4) One mechanism of action is likely to involve increased concentrations of the inhibitory transmitter GABA in the brain. Increased concentrations of GABA are associated with a

decrease in CNS activity and this action may, therefore, be involved in the reported sedative activity.

In vitro and animal studies

Sedative properties have been documented for valerian and have been attributed to both the volatile oil and valepotriate fractions.(16, 17) Screening of the volatile oil components for sedative activity concluded valerenal and valerenic acid to be the most active compounds, causing ataxia in mice at a dose of 50 mg/ kg by intraperitoneal injection.(16) Further studies in mice described valerenic acid as a general CNS depressant similar to pentobarbitone, requiring high doses (100 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection) for activity.(18) A dose of 400 mg/kg resulted in muscle spasms, convulsions and death.(18) Valerenic acid was also reported to prolong pentobarbitone-induced sleep in mice, resulting in a hangover effect. Biochemical studies have documented that valerenic acid inhibits the enzyme system responsible for the central catabolism of GABA.(19) An aqueous extract of roots and rhizomes of V. officinalis (standardised to 55 mg valerenic acids per 100 g extract) inhibited the uptake and stimulated the release of radiolabelled GABA in isolated synaptosomes from rat brain cortex.(20, 21) Further work suggested that this aqueous extract of valerian induces the release of GABA by reversal of the GABA carrier, and that the mechanism is Naþ dependent and Ca2þ independent.(21) The extract contained a high concentration of GABA (about 5 mmol/L) which was shown to be sufficient to induce the release of radiolabelled GABA by this type of mechanism.(22) Aqueous and hydroalcoholic (ethanol) extracts of valerian root displaced radiolabelled muscimol binding to synaptic membranes (a measure of the influence of drugs on GABAA receptors). However, valerenic acid (0.1 mmol/L) did not displace radiolabelled muscimol in this model.(23) Other in vitro studies using rat brain tissue have shown that hydroalcoholic and aqueous total extracts of V. officinalis root, and an aqueous fraction derived from the hydroalcoholic extract, show affinity for GABAA receptors, although far lower than that of the neurotransmitter itself.(24) However, a lipophilic fraction of the hydroalcoholic extract, hydroxyvalerenic acid and dihydrovaltrate did not show any affinity for the GABAA receptor in this model.

The effects of valerian extracts on benzodiazepine binding to rat cortical membranes have also been explored. Very low concentrations of ethanolic extract of V. officinalis had no effect on radiolabelled flunitrazepam binding in this model, although

concentrations of 10 10 to 10 8 mg/mL increased radiolabelled flunitrazepam binding with an EC50 of 4.13 10 10 mg/mL.(25)

However, flunitrazepam binding was inhibited at higher concentrations (0.5–7.0 mg/mL) of valerian extract (IC50 4.82 10 1 mg/ mL). In other investigations, valerian extract potentiated radiolabelled GABA release from rat hippocampal slices, and inhibited synaptosomal GABA uptake, confirming the effects of valerian extract on GABAA receptors.(25)

Radiolabelled ligand binding studies have also shown that constituents of dichloromethane and petroleum ether extracts of

valerian have strong binding affinities for 5-HT5a receptors but only weak binding affinities for 5-HT5b receptors.(26) At

concentrations of 50 mg/mL, the petroleum ether and dichloromethane extracts inhibited binding of radiolabelled lysergic acid diethylamide to 5-HT5a receptors by 86% and 51%, respectively. Generation of an IC50 curve for the petroleum ether extract produced a biphasic curve. Valerenic acid, a constituent of both extracts, had an IC50 of 17.2 mmol/L. In other radiolabelled ligand binding experiments, a 45% methanol extract of valerian root

(drug to extract ratio 4–6 : 1; containing valerenic acids 0.388%, and no valepotriates) had an IC50 value of 450 mg/mL at melatonin-1 (ML) receptors obtained from chicken brain, whereas a 45% methanol extract of hops' cones (containing flavonoids 0.479%, calculated as rutin) had an IC50 value of 71 mg/mL at these receptors. A preparation (ZE-91019) containing both extracts had an IC50 value of 97 mg/mL, suggesting a synergistic action between the two extracts at ML1 receptors.(27)

CNS-depressant activities in mice following intraperitoneal injection have been documented for the valepotriates and for their degradation products, although activity was found to be greatly reduced following oral administration.(28) A study explored the effects of a mixture of valepotriates on the behaviour of diazepamwithdrawn male Wistar rats in the elevated plus-maze test (a measure of the anxiolytic or anxiogenic properties of drugs).(29) Rats were given diazepam (up to 5 mg/kg for 28 days) then vehicle only for three days to induce a withdrawal syndrome. Rats given diazepam or a mixture of valepotriates (stated to contain dihydrovaltrate 80%, valtrate 15% and acevaltrate 5%) administered intraperitoneally (12 mg/kg) spent a significantly greater proportion of time in the 'open' arms of the maze than did those in the control group.

Another specific valepotriate fraction, Vpt2, has been documented to exhibit tranquillising, central myorelaxant, anticonvulsant, coronary-artery dilating and anti-arrhythmic actions in mice, rabbits, and cats.(30, 31) The fraction was reported to prevent arrhythmias induced by Pituitrin vasopressin and barium chloride, and to exhibit moderate positive inotropic and negative chronotropic effects.

Antispasmodic activity on intact and isolated guinea-pig ileum has been documented for isovaltrate, valtrate and valeranone.(32) This activity was attributed to a direct action on the smooth muscle receptors rather than ganglion receptors. Valerian oil has been reported to exhibit antispasmodic activity on isolated

guinea-pig uterine muscle,(33) but proved inactive when tested in vivo.(34)

In-vitro inactivation of complement activation has been reported for the valepotriates.(35)

In-vitro cytotoxicity (inhibition of DNA and protein synthesis, and potent alkylating activity) has been documented for the valepotriates, with valtrate stated to be the most toxic compound.(36) Valepotriates (valtrate and didrovaltrate) isolated from the related species Valeriana wallichii, and baldrinal (a degradation product of valtrate) have been tested for their cytotoxic activity in vitro using cultured rat hepatoma cells. Valtrate was the most active compound in this system, leading to a 100% mortality of hepatoma cells after 24 hours' incubation at a concentration of 33 mg/mL.(37) More detailed studies using the same system showed that didrovaltrate demonstrated cytotoxic activity when incubated at concentrations higher than 8 mg/mL of culture (1.5 10 5 mol/L) and led to 100% cellular mortality with 24 hours of incubation at a concentration of 66 mg/mL. The cytotoxic effect of didrovaltrate was irreversible within two hours of incubation with hepatoma cells. In mice, administration of intraperitoneal didrovaltrate led to a regression of Krebs II ascitic tumours, compared with control.(37) A subsequent in vivo study, in which valtrate was administered to mice (by intraperitoneal injection and by mouth), did not report any toxic effects on haematopoietic precursor cells when compared with control groups.(38) The valepotriates are known to be unstable compounds in both acidic and alkaline media and it has been suggested that their in vivo toxicity is limited due to poor absorption and/or distribution.(2) Baldrinal and homobaldrinal, decomposition

|

|

Valerian |

583 |

|

products of valtrate and isovaltrate respectively, have exhibited |

|

|||

direct mutagenic activity against various Salmonella strains in |

|

|||

vitro.(39) |

|

|

|

|

Clinical studies |

|

|

|

|

Pharmacokinetics |

There are only limited data on the |

|

||

pharmacokinetics of valerian preparations and their constituent |

|

|||

compounds. The pharmacokinetics of valerenic acid were |

|

|||

explored in a single-dose study involving six healthy adults who |

|

|||

received a 70% ethanol extract of valerian root (LI-156, |

|

|||

Sedonium, Lichtwer Pharma; drug to extract ratio 5 : 1) 600 mg |

|

|||

in the morning. For five participants, maximum serum concentra- |

|

|||

tions of valerenic acid occurred between one and two hours after |

|

|||

valerian administration and ranged |

from 0.9 to 2.3 ng/mL; |

|

||

valerenic acid concentrations were measurable for at least five |

|

|||

hours after valerian administration.(40) For one subject, maximum |

|

|||

concentrations occurred at both one and five hours after valerian |

|

|||

administration. The mean (standard deviation (SD)) elimination |

|

|||

half-life (t1/2) for valerenic acid was 1.1 (0.6) hours and the mean |

|

|||

(SD) area under the plasma concentration time curve was 4.80 |

|

|||

(2.96) mg/mL/hour. Further investigation of the pharmacokinetics |

|

|||

of valerian is required, including those of different manufacturers' |

|

|||

preparations and their constituents. |

|

|

|

|

Sleep disorders, hypnotic activity |

Numerous studies |

have |

|

|

explored the effects of valerian preparations on subjective (e.g. |

|

|||

participants' self-assessment of sleep quality) and/or objective (e.g. |

|

|||

sleep structure, such as duration of rapid eye movement (REM) |

|

|||

sleep or slow-wave sleep) sleep parameters. Collectively, the |

|

|||

findings of these studies are difficult to interpret, as different |

|

|||

studies have assessed different valerian preparations and different |

|

|||

dosages, and some have involved healthy volunteers whereas |

|

|||

others have involved patients with diagnosed sleep disorders. In |

|

|||

addition, other studies have used different subjective and/or |

|

|||

objective outcome measures, and some have been conducted in |

|

|||

sleep laboratories, whereas others have assessed participants |

|

|||

receiving valerian whilst sleeping at home. Overall, several, but |

|

|||

not all, studies have documented a hypnotic effect for valerian |

|

|||

preparations with regard to subjective measures of sleep quality, |

|

|||

and some have documented effects on objective measures of sleep |

|

|||

structure. There is a view that investigating subjective measures of |

|

|||

sleep quality may be the most appropriate or relevant form of |

|

|||

assessment.(41) Several trials, including the most recent studies, |

|

|||

particularly those involving individuals with sleep disorders rather |

|

|||

than healthy volunteers, are summarised below. |

|

|

||

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover |

|

|||

study involving 16 patients with previously established psycho- |

|

|||

physiological insomnia according to International Classification |

|

|||

of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) criteria and confirmed by polysomno- |

|

|||

graphy assessed the effects of single-dose and longer-term |

|

|||

administration of valerian root extract on objective parameters |

V |

|||

of sleep structure and subjective parameters of sleep quality.(42) |

||||

Participants received a 70% ethanol extract of valerian root (LI- |

|

|||

156; drug to extract |

ratio 5 : 1) 600 mg, or placebo, one |

hour |

|

|

before bedtime for 14 days, followed by a wash-out period of 13 days before crossing over to the other arm of the study. There were no statistically significant effects on objective and subjective parameters of sleep following single-dose valerian administration. Similarly, after long-term treatment, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in sleep efficiency (ratio of time spent asleep to time spent in bed). There was a statistically significant difference with valerian on parameters of slow-wave

584 Valerian

sleep, compared with baseline values, which did not occur with placebo. However, it is not clear if this difference was significantly different for valerian, compared with placebo, as no p-value was given.

The effects of repeated doses of the same valerian root extract (LI-156) were assessed in a randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled, parallel-group trial involving 121 patients with insomnia not due to organic causes.(43) Participants received valerian extract 600 mg, or placebo, one hour before bedtime for 28 days. At the end of the study, clinical global impression scores were significantly higher for the valerian group than for the placebo group.

A crossover study assessing the same valerian root extract (LI156) involved 16 individuals aged 50 to 64 years with mild sleep complaints (e.g. difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings) who received a single 300 mg or 600 mg dose of the extract, or placebo, at 10 pm on one occasion, with a 6-day wash-out period before crossing over to each of the other arms of the study.(44) Participants underwent a battery of tests designed to assess objective and subjective measures of sleep at 7.05 am on the morning after each treatment intervention. There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups for any of the outcome variables measured (p > 0.05).

In a randomised, double-blind, pilot study, 14 older women who were poor sleepers received valerian aqueous extract (Valdispert forte; drug to extract ratio 5–6 : 1), or placebo (n = 6), for eight consecutive days.(15) Valerian 405 mg was administered one hour before sleep for one night in the laboratory, then taken three times daily for the following seven days. Valerian recipients showed an increase in slow-wave sleep, compared with baseline values. However, valerian had no effect on sleep onset time, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or on self-rated sleep quality, when compared with placebo. In another randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving older participants, 78 hospitalised patients with various chronic conditions in addition to difficulty sleeping received an aqueous valerian root extract (Baldrian Dispert) 270 mg daily, or placebo, for 14 days.(45) At the end of the study, sleep latency and sleep duration were significantly improved in the valerian group, compared with the placebo group (p < 0.001 for both).

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 128 volunteers explored the effects of an aqueous extract of valerian root (400 mg) and a proprietary preparation of valerian and hops (Hova) on subjective measures of sleep quality. Each participant took each of the three preparations at night for three non-consecutive nights.(14) On the basis of participants' selfassessment, valerian significantly reduced sleep latency (time to onset of sleep) and improved sleep quality, compared with placebo (p < 0.05). Subgroup analysis suggested that the effects of valerian were most marked among participants who described themselves as 'poor' or 'irregular' sleepers.(14) It was reported that the

Vvalerian–hops preparation did not significantly affect sleep latency or sleep quality, compared with placebo, only that the valerian– hops preparation administration was associated with an increase in the number of reports of 'feeling more sleepy than usual the next morning' (i.e. a 'hangover' effect). The authors were unable to explain this discrepancy in the results for the two preparations.

In a subsequent study, eight individuals with mild insomnia each received aqueous valerian root extract 450 mg, 900 mg or

placebo, in a random-order experimental design over almost three weeks.(46) The time to the first period of five consecutive minutes without movement, measured using wrist-worn activity meters, was used as an objective measure of sleep latency. For this

parameter, valerian 450 mg significantly reduced the mean sleep latency, compared with placebo, although there was no further reduction in sleep latency with valerian 900 mg. Subjective assessments indicated that participants were more likely to experience a 'hangover' effect with valerian 900 mg.(46)

The effects of a valerian root/rhizome extract (tablets containing 225 mg extract equivalent to 1000 mg crude drug, standardised for total valerenic acids 2.94 mg, valerenal 0.46 mg and valtrates 1.23 mg; Mediherb, Australia) two tablets at night half an hour before going to bed on self-assessed sleep parameters were assessed in a series of randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled, 'n-of-1' crossover trials involving 24 patients with chronic insomnia diagnosed by a general practitioner. The trials were conducted in a general practice setting and involved three pairs of one-week treatments with valerian extract and placebo (i. e. each n-of-1 trial lasted for six weeks).(47) Statistical analyses found that participants did not show any response to valerian for any of the outcome measures either individually or when individual results were pooled. N-of-1 trials have recognised limitations, including some which can increase the possibility of false negative results, although these were taken into consideration during the analysis of these data. Investigation of dosage regimens involving higher doses of this extract administered for longer periods may be warranted.(47)

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted entirely over the Internet, 391 adults who scored at least 40 points on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scale and who reported having sleeping problems on at least two occasions received two capsules containing valerian extract (each containing valerenic acids 3.2 mg; no further details of preparation provided) one hour before bedtime, capsules containing kava extract (each

containing total kavalactones 100 mg) one three times daily, or placebo, for 28 days.(48) At the end of the study, there were no

statistically significant differences between valerian and placebo with respect to the primary outcome measure changes from baseline in Insomnia Severity Index scores. The study also assessed effects on anxiety (see Anxiety, depression and other conditions).

The effects of preparations of valerian root extract have been compared with those of certain benzodiazepines. In a randomised, double-blind trial, 75 individuals with non-organic and nonpsychiatric insomnia received valerian root extract (drug to extract

ratio 5 : 1) 600 mg or oxazepam 10 mg; both treatments were taken 30 minutes before going to bed for 28 days.(49) At the end of the

treatment period, sleep quality had improved significantly (p < 0.001) in both groups, compared with baseline values, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p= 0.70). The effects of a combination valerian preparation were compared with those of bromazepam in a three-week, randomised, double-blind trial involving patients with 'environmental' sleep disorders (temporary dyscoimesis and dysphylaxia) according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-IV criteria.(50) The combination preparation, containing valerian 200 mg and hops extract 45.5 mg, was reported to be equivalent to bromazepam 3 mg with regard to sleep quality. These findings require confirmation in rigorous studies designed specifically to

test for equivalence.

Several of the studies summarised above(14, 15, 43, 45, 46) were included in a systematic review of nine randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of monopreparations of valerian.(51) All trials included in the review had different designs and assessed the effects of different valerian preparations administered according to different dosage regimens, so the validity of considering their results collectively is questionnable. The review concluded that the

evidence for valerian as a treatment for insomnia is inconclusive and that there is a need for further rigorous trials.

Several other studies have assessed the effects of valerian extract in combination with other herb extracts, such as hops (Humulus

lupulus) and/or melissa (Melissa officinalis), on measures of sleep.(52–56)

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallelgroup trial, 184 adults with mild insomnia received two tablets of a valerian–hops preparation (each tablet containing 187 mg of a 45% methanol extract of valerian, drug to extract ratio 5–8 : 1, and 42 mg of a 45% methanol extract of hops, drug to extract ratio 7–10 : 1; n = 59), or placebo (n = 65), each night for 28 days;

a third study arm received diphenhydramine 50 mg each night for 14 days followed by placebo for 14 days (n = 60).(52) At the end of

the study, there was no statistically significant difference in sleep latency between the valerian–hops group and the placebo group (p

=0.08). There were no statistically significant differences between groups with respect to the sleep continuity variables, as measured by polysomnography, nor in the duration of sleep stages 3 and 4, and REM sleep. The physical component, but not the mental component, of the quality-of-life measure used was significantly improved in the valerian–hops group, compared with the placebo group after 28 days (p = 0.028).

A randomised, double-blind trial involving healthy volunteers who received Songha Night (V. officinalis root extract 120 mg and M. officinalis leaf extract 80 mg) three tablets daily taken as one dose 30 minutes before bedtime for 30 days (n = 66), or placebo (n

=32), found that the proportion of participants reporting an improvement in sleep quality was significantly greater for the

treatment group, compared with the placebo group (33.3% versus 9.4%, respectively; p = 0.04).(54) However, analysis of visual analogue scale scores revealed only a slight, but statistically nonsignificant, improvement in sleep quality in both groups over the treatment period. Another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving patients with insomnia who received Euvegal forte tablets (containing valerian extract 160 mg and lemon balm extract 80 mg) two daily for two weeks reported significant improvements

in sleep quality in recipients of the herbal preparation, compared with placebo recipients.(55) A placebo-controlled study involving 'poor sleepers' who received Euvegal forte reported significant

improvements in sleep efficiency and in sleep stages 3 and 4 in the treatment group, compared with placebo recipients.(56)

In a single-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involving 12 healthy volunteers, two different single doses of a combination preparation (ZE-91019) containing extracts of valerian and hops

(valerian 500 mg, hops 120 mg; valerian 1500 mg, hops 360 mg) were assessed for their effects on EEG recordings.(57) Some slight effects on the quantitative EEG were documented following administration of the higher dose valerian–hops combination, suggesting effects on the central nervous system. The same preparation (two or six tablets as a single dose; n = 16), in addition to caffeine 200 mg, was administered to healthy volunteers in a controlled (caffeine 200 mg plus placebo; n = 16) study which aimed

to determine the pharmacodynamics of co-administration of the two preparations by measuring EEG responses.(58) EEG recordings at one hour after administration indicated that the lower dose of the valerian–hops preparation reduced caffeine-induced arousal and the higher dose inhibited the caffeine-induced arousal. It was stated

that this indicates that the valerian–hops combination preparation acts via a central adenosine mechanism,(58) although which constituents are responsible for this effect is not known.

The effects of a related species, V. edulis, on sleep parameters were assessed in a preliminary randomised, double-blind, placebo-

Valerian 585

controlled, crossover trial involving five male children (7 to 14 years) with intellectual deficits (intelligence quotient < 70).(59) Participants received tablets containing V. edulis dried crushed root 500 mg (containing 5.52 mg valtrate/isovaltrate, didrovaltrate and acevaltrate were absent; Mediherb, Australia), or placebo (which contained 25 mg dried V. edulis root to achieve blinding for odour), at a dose of 20 mg/kg body weight administered each night at least one hour before bedtime for two weeks following a two-week run-in period. Participants underwent a one-week wash-out period before crossing over to the other arm of the study. Time awake, total sleep time and sleep quality all improved in the valerian group, compared with baseline values (p < 0.05 for each), whereas only sleep quality improved in the placebo group, compared with baseline values (p = 0.04).(59) However, as no statistical analyses appear to have been conducted to examine any differences between the valerian and placebo groups, these findings raise the hypothesis that dried V. edulis root has effects on certain sleep parameters and this requires testing in welldesigned clinical trials involving adequate numbers of participants. In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, a preparation of constituents (Valmane, comprising didrovaltrate 80%, valtrate 15% and acevaltrate 5%; Whitehall Pharmaceuticals) obtained from the root of V. wallichii, another related species, was assessed for its effects on sleep parameters in 19 individuals who had undergone withdrawal from benzodiazepines.(60) Participants received the valerian preparation at a dose of 100 mg, or placebo, three times daily starting two days after completing benzodiazepine withdrawal and continuing for 15 days. At the end of the study, wake time after sleep onset was significantly reduced in the valerian group compared with the placebo group, whereas sleep latency was significantly improved in the placebo group, compared with the valerian group (p < 0.05 for both). The study has methodological limitations, including the small sample size, and these apparently conflicting findings require further investigation in well-designed clinical trials involving adequate numbers of participants.

Anxiety, depression and other conditions |

The effects |

of a |

|

preparation containing a mixture of valepotriate compounds |

|

||

(stated to contain dihydrovaltrate 80%, valtrate 15%, acevaltrate |

|

||

5%) were assessed in a randomised, double-blind, placebo- |

|

||

controlled, parallel-group trial involving 36 patients with general- |

|

||

ised anxiety disorder diagnosed according to DSM-III-R (Diag- |

|

||

nostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) criteria.(61) |

|

||

Participants received capsules containing the valepotriate mixture |

|

||

50 mg, diazepam 2.5 mg, or placebo, for four weeks according to a |

|

||

flexible dosing regimen (one to three capsules of the active |

|

||

treatments) depending on the participants' response. At the end of |

|

||

the study, there were no statistically significant differences |

|

||

between the three groups for the primary outcome variable |

|

||

mean total Hamilton Anxiety scale scores (p > 0.05) and for |

|

||

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scores. As a sample size |

V |

||

calculation was not carried out, and as the study involved only a |

|||

small sample, it is possible that the trial did not have sufficient |

|

||

statistical power to detect differences (if they exist) between the |

|

||

three groups. |

|

|

|

In another randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, |

|

||

conducted entirely over the Internet, 391 adults who scored at least |

|

||

40 points on the STAI scale and who reported having sleeping |

|

||

problems on at least two occasions received two capsules |

|

||

containing valerian extract (each containing |

valerenic |

acids |

|

3.2 mg; no further details of preparation provided) one |

hour |

|

|

before bedtime, capsules containing kava extract (each containing |

|

||

586 Valerian

total kavalactones 100 mg) one three times daily, or placebo, for 28 days.(48) At the end of the study, there were no statistically significant differences between valerian and placebo with respect to the primary outcome measure changes from baseline in STAI anxiety scores. The study also assessed effects on insomnia (see Sleep disorders, hypnotic activity).

The effects of valerian have also been assessed on mental stress in laboratory-based studies involving healthy volunteers. In a randomised controlled trial, 36 participants received valerian root extract (LI-156) 1200 mg (n = 18) or kava root extract (LI-150) 120 mg daily for seven days; a third group of participants acted as a no-treatment control group.(62) Participants' heart rate and blood pressure measurements were taken before, during and after a mental stress test at baseline and seven days later following treatment. The results suggested that increases in systolic blood pressure in response to mental stress were lower in the valerian group, compared with those in the control group. These results, however, can only be considered preliminary as the control group did not receive placebo. Further investigation using a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial design is required.(62)

The effects of another valerian extract at a dose of 100 mg (no further details of preparation given), with or without propranolol 20 mg, on activation and performance under experimental social stress conditions were assessed in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 48 healthy volunteers.(63) Valerian was reported to have no statistically significant effect on physiological activation and to lead to less intensive subjective feelings of somatic arousal, compared with control.

Several studies have assessed the effects of combinations of valerian and other herbal ingredients in patients with anxiety or depression. In a randomised, double-blind study involving 100 patients with anxiety, a combination of valerian and St John's wort was significantly more effective than diazepam according to a physician's rating scale and a patient's self-rating scale.(64) In a randomised, double-blind trial involving 162 patients with dysthymic disorders, the effects of a valerian and St John's wort combination preparation (Sedariston) were compared with those of amitriptyline 75–150 mg.(65) Another randomised, double-blind trial, involving 100 patients with mild-to-moderate depression compared Sedariston with desipramine 100–150 mg.(66) Pooling the results of these two studies indicated there were 88 (68%) treatment responders in the Sedariston group and 66 (50%) in the group that received standard antidepressants.(67) This difference was not statistically significant. As valerian root is not known for antidepressant effects, it is likely that any antidepressant activity observed in the studies described above is attributable to St John's wort.

Several studies have assessed the effects of valerian, or herbal combination products containing valerian, on performance the morning after treatment (see Side-effects, Toxicity).

VSide-effects, Toxicity

Clinical data

There are only limited clinical data on safety aspects of valerian preparations from clinical trials. Clinical trials have the statistical power to detect only common, acute adverse effects and postmarketing surveillance-type studies are required to establish the safety of valerian preparations, particularly with long-term use.

Few controlled clinical trials of valerian preparations have provided detailed information on safety. Where adverse event data were provided, randomised, placebo-controlled trials involving

healthy volunteers or patients with diagnosed insomnia reported that adverse events with valerian were mild and transient, and that

the types and frequency of adverse events reported for valerian were similar to those for placebo.(44, 47, 51, 68) One study involving

small numbers of patients reported a lower frequency of adverse events with valerian than with placebo; the authors did not suggest an explanation for this.(42) Studies comparing valerian

preparations with benzodiazepines have reported that valerian root extract (LI-156) 600 mg daily for 14 days(68) or 28 days(49) had

a more favourable adverse effect profile than flunitrazepam 1 mg daily for 14 days(68) and oxazepam 10 mg daily for 28 days,(49)

respectively.

There is an isolated report of cardiac complications and delirium associated with valerian root extract withdrawal in a 58- year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension and congestive heart failure.(69) The man had been taking valerian root extract (530 mg to 2 g, five times daily), multiple other medications and had undergone surgery, therefore a causal link with valerian could not be made. There have been isolated reports of hepatotoxic reactions following the use of combination products containing valerian, although these products contained other herbal ingredients which could also be implicated.(70, G18, G21) Several other reports document hepatotoxic reactions with single-ingredient valerian products, although it is possible that these were idiosyncratic reactions.(71) There is a lack of data on the safety of the long-term use of valerian.

Cases of individuals who had taken overdoses of valerian or valerian-containing products have been documented. One case involved an 18-year-old female who ingested 40–50 capsules of powdered valerian root 470 mg, approximately 20 times therapeutic doses.(72) The patient presented three hours after ingestion with fatigue, crampy abdominal pain, chest tightness, tremor and lightheadedness. Liver function test values were normal; a urine screen tested positive for tetrahydrocannabinol. The patient was treated with activated charcoal, and symptoms resolved within 24 hours. Several cases (n = 47) have been documented of overdose with a combination valerian-containing product ('Sleep-Qik'; valerian dry extract 75 mg, hyoscine hydrobromide 0.25 mg,

cyproheptadine |

hydrochloride |

2 mg).(73, 74) Individuals |

had |

ingested tablets |

equivalent to |

0.5–12 g valerian extract. |

Liver |

function tests were carried out for most patients and yielded results within normal ranges.

Effects on cognitive and psychomotor performance

Studies assessing the effects of valerian preparations on measures of performance report conflicting results: some suggest that there is slight impairment for a few hours following ingestion of single doses of valerian, whereas other studies report no effects on performance following administration. As these studies have assessed the effects of different preparations of valerian, the conflicting results may simply relate to differences in the chemical composition of the products tested. Further research is needed to establish whether or not specific valerian preparations impair performance following ingestion. In contrast, the few studies investigating the potential for impaired performance the morning following treatment (i.e. 'hangover' effects) with valerian preparations have found that such impairment does not occur, at least with the preparations and dosages tested. Several of the studies examining these aspects are summarised below.

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, nine healthy participants each received a 70% ethanol extract of valerian root (containing valerenic acid 0.25%; drug to

extract ratio 4 : 1) 500 mg, 1000 mg, and triazolam 0.25 mg, as a single dose with a one-week wash-out period between treatments. There were no statistically significant differences in the outcomes of cognitive and psychomotor tests performed before and two, four and eight hours after each treatment dose between the valerian and placebo groups.(75) A similar finding was obtained in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involving ten healthy participants who underwent assessments of mood and psychomotor performance before and after receiving a valerian root extract (LI-156) at doses of 600, 1200 and 1800 mg, and diazepam 10 mg, with a one-week wash-out period between treatments. Compared with placebo, valerian had no statistically significant effects on mood or on cognitive and psychomotor performance.(76)

The two studies described above involved younger (aged less than 30 years) participants. Another randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study involved 14 healthy older participants (mean age 71.6 years, range 65–89 years) who received valerian 400 mg and 800 mg (Jamieson, Canada; subsequently reported to contain valerenic acid, 1-acetoxyvalerenic acid and 1- hydroxyvalerenic acid 0.63%), temazepam 15 mg and 30 mg, and diphenhydramine 50 mg and 75 mg, with a three-day wash-out period between treatments. No statistically significant differences on measures of psychomotor performance or sedation were found for valerian, compared with placebo.(77)

In a randomised, double-blind trial involving 102 healthy volunteers, the effects of single-dose valerian extract (LI-156) 600 mg on reaction time, alertness and concentration were compared with those of flunitrazepam 1 mg and placebo.(68) The treatment was administered in the evening and psychometric tests were carried out the next morning. After a one-week wash-out period, 91 volunteers continued with the second phase of the study, which comprised 14 days' administration of valerian extract 600 mg or placebo. Single-dose valerian extract administration did not impair reaction time, concentration or coordination. A 'hangover' effect was reported by 59% of flunitrazepam recipients, compared with 32% and 30% of placebo and valerian recipients, respectively (p < 0.05 for flunitrazepam versus valerian). At the end of the 14-day study, there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.45) between valerian extract and placebo on mean reaction time (a measure of performance).

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 80 volunteers compared the 'hangover' effects of tablets containing valerian and hops, a syrup containing valerian only, and flunitrazepam 1 mg, all given as a single dose.(78) Performance the morning after treatment, measured both objectively and subjectively, was impaired only in the flunitrazepam group.(78) Side effects occurred more frequently in the flunitrazepam group (50%), compared with the valerian and placebo groups (10%). In a further placebo-controlled study involving 36 volunteers who received valerian–hops tablets, valerian syrup, or placebo, and who underwent a battery of cognitive psychomotor tests 1–2 hours after drug administration, there was a slight, but statistically significant, impairment in vigilance with valerian syrup and impairment in the processing of complex information with valerian–hops tablets, compared with placebo.(78)

Preclinical data

Toxicological studies documented in the older literature have reported an LD50 of 3.3 mg/kg for an ethanolic extract of valerian administered intraperitoneally in rats, and that daily doses of 400– 600 mg/kg, administered intraperitoneally for 45 days, did not lead

|

Valerian |

587 |

|

to any changes in weight, blood or urine measurements, compared |

|

||

with controls.(1) Literature cited in a review of the safety of |

|

||

valerian describes LD50 values of 64 mg/kg for valtrate, 125 mg/kg |

|

||

for didrovaltrate and 150 mg/kg for acevaltrate in mice after |

|

||

intraperitoneal injection.(G21) Another study in mice reported that |

|

||

valerenic acid 150 mg/kg, given by intraperitoneal |

injection, |

|

|

caused muscle spasms and that 400 mg/kg caused heavy convul- |

|

||

sions.(18) The latter dose was lethal to six of seven mice. |

|

||

In vitro cytotoxicity and mutagenicity have been documented |

|

||

for the valepotriates. The clinical significance of this is unclear, |

|

||

since the valepotriates are known to be highly unstable and, |

|

||

therefore, probably degrade when taken orally. Only traces of |

|

||

valepotriates or their degradation products (in part, baldrinals) |

|

||

are likely to be found in finished products.(G80) |

|

|

|

In toxicological studies in rats, there were no changes in bile |

|

||

value and liver enzyme activity in animals treated with a valerian |

|

||

preparation (Indena, Italy; no further details provided) as a single |

|

||

dose (0.31 to 18.6 g/kg) or 3.1 g/kg for 28 days. In vitro, incubation |

|

||

of human hepatoma cells with the same valerian preparation at a |

|

||

concentration of 20 mg/mL led to increased cell death, compared |

|

||

with values for control.(79) No such effect was seen for the valerian |

|

||

preparation at a concentration of 2 mg/mL, when compared with |

|

||

control. |

|

|

|

A study in rats involved the administration of valepotriates (6, |

|

||

12 and 24 mg/kg administered orally) during pregnancy up to the |

|

||

19th day when animals were sacrificed.(80) There were no |

|

||

differences between valepotriate-treated rats and control rats as |

|

||

determined by fetotoxicity and external examination studies, |

|

||

although the two highest doses of valepotriates were associated |

|

||

with an increase in retarded ossification evident on internal |

|

||

examination. |

|

|

|

Contra-indications, Warnings |

|

|

|

Intake of valerian preparations immediately (up to two hours) |

|

||

before driving or operating machinery is not recommended.(G80) |

|

||

The effect of valerian preparations may be enhanced by |

|

||

consumption of alcohol, so excessive consumption of alcohol |

|

||

whilst receiving treatment with valerian root preparations should |

|

||

be avoided.(G80) Patients should seek medical advice if symptoms |

|

||

worsen beyond two weeks' continuous treatment with valer- |

|

||

ian.(G80) Patients with known sensitivity to valerian should not use |

|

||

valerian root preparations.(G80) |

|

|

|

Drug interactions Only limited data on the potential for |

|

||

pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions with other |

|

||

medicines administered concurrently are available for valerian root |

|

||

preparations. In view of the documented pharmacological actions |

|

||

of valerian the potential for preparations of valerian to interfere |

|

||

with other medicines administered concurrently, particularly those |

|

||

with similar or opposing effects, should be considered. In |

|

||

particular, co-medication with barbiturates and other sedatives |

V |

||

is not recommended because of the potential for |

excessive |

||

sedation.(G80) |

|

|

|

In an open-label, fixed-treatment, crossover study, 12 healthy volunteers received two tablets containing 500 mg of a 70%

ethanol extract of valerian root (containing total valerenic acids 5.51 mg per tablet) each night for two weeks.(81) The probe drugs

dextromethorphan 30 mg and alprazolam 2 mg were administered before and after valerian exposure to assess the effects of valerian on CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in dextromethorphan pharmacokinetics after valerian exposure, compared with baseline values.

588 Valerian

The maximum plasma concentration of alprazolam was significantly increased following valerian exposure, compared with baseline values (p < 0.05) although there were no statistically significant differences in other pharmacokinetic parameters measured. Another study involved healthy volunteers who received valerian root extract (subsequently found to contain quantities of valerenic acid only at the limits of detection (10 ng/mL)) 125 mg three times daily for 28 days.(82) No statistically significant changes in phenotypic ratios for CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 and CYP3A4/5 were observed for valerian, although the valerian product tested may not be representative of other valerian preparations and their effects on CYP enzymes.(82) In in-vitro experiments, aqueous, ethanol and acetonitrile extracts of commercial monopreparations and combination preparations of valerian root inhibited cytochrome P450 3A4 activity and P- glycoprotein transport, as determined by an ATPase assay.(83)

Pregnancy and lactation The safety of valerian during

pregnancy and lactation has not been established and, therefore, its use should be avoided.(G80)

Preparations

Proprietary single-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Nervisatis. Australia: Herbal Sleep Formula. Belgium: Dormiplant; Relaxine; Valerial. Brazil: Noctaval; Recalm; Sonoripan; Valeriane; Valerimed; Valerin; Valerix; Valezen; Valmane. Canada: Nytol Natural Source; Sleep-Eze V Natural; Unisom Natural Source. Chile: Sominex. Czech Republic: Koren Kozliku Lekarskeho; Valdispert. Finland: Valrian. Germany: Baldorm; Baldriparan Stark; Baldrivit; Baldurat; Cefaluna; Dolestan; Euvegal Balance; Luvased mono; Recvalysat; Sedonium; Sporal mono; Valdispert. Israel: Relaxine; Valeton. Italy: Ticalma. Mexico: Neolaikan. Netherlands: Dormiplant; Valdispert. Portugal: Valdispert. Russia: Novo-Passit (Ново-Пассит). South Africa: Calmettes. Spain: Ansiokey; Coenrelax; Valdispert; Valeriana Orto; Valsedan. Sweden: Baldrian-Dispert; Neurol; Valerecen. Switzerland: Baldriparan pour la nuit; Natu-Seda; ReDormin; Sedasol eco natura; Sedonium; Valdispert. UK: Phytorelax; Sedonium.

Venezuela: Floral Pas.

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Armonil; Dioxicolagol; Nervocalm; SDN 200; Sedante Dia; Serenil; Sigmasedan; Valeriana Oligoplex. Australia: Calmo; Coleus Complex; Dan Shen Compound; Executive B; Extralife Sleep-Care; Goodnight Formula; Humulus Compound; Lifesystem Herbal Plus Formula 2 Valerian; Macro Anti-Stress; Multi-Vitamin Day & Night; Natural Deep Sleep; Pacifenity; Passiflora Complex; Passionflower Plus; Prosed-X; Relaxaplex; Valerian Plus Herbal Plus Formula 12;

VValerian. Austria: Baldracin; Baldrian AMA; Eryval; Euvekan; Hova; Nervenruh; Nerventee St Severin; Sedadom; Sedogelat; Songha; Species nervinae; Thymoval; Valin Baldrian; Wechseltee St Severin. Belgium: Natudor; Seneuval; Songha. Brazil: Passicalm; Sominex; Sonhare. Canada: Herbal Nerve; Herbal Relax; Herbal Sleep Aid; Herbal Sleep Well. Chile: Armonyl; Recalm; Valupass. Czech Republic: Baldracin; Bio-Strath; Contraspan; Dr Theiss Rheuma Creme; Dr Theiss Schwedenbitter; Euvekan; Hertzund Kreislauftee; Nervova Cajova Smes; Novo-Passit; Persen; Sanason; Schlaf-Nerventee N;

Songha Night; Species Nervinae Planta; Valofyt Neo; Visinal. France: Biocarde; Euphytose; Mediflor Tisane Calmante Troubles du Sommeil No 14; Mediflor Tisane Circulation du Sang No 12; Neuroflorine; Passinevryl; Spasmine; Sympaneurol; Tranquital. Germany: Ardeysedon; Avedorm duo; Baldrian-Dispert Nacht; Baldriparan N Stark; Biosedon; Boxocalm; Cefasedativ; Dormarist; Dormeasan; Dormo-Sern; Dormoverlan; Dr. Scheffler Bergischer Krautertee Nervenund Beruhigungstee; Dreierlei; Euvegal Entspannungsund Einschlaftropfen; Gutnacht; Gutnacht; Heumann Beruhigungstee Tenerval; Hingfong-Essenz Hofmanns; Hyperesa; Klosterfrau Beruhigungs Forte; Kytta-Sedativum; Leukona-Beruhigungs- bad; Luvased; Moradorm S; Mutellon; Nervendragees; Nervenkapseln; Nervoregin forte; Neurapas; Nitrangin compositum; Oxacant-sedativ; Pascosedon; Phytonoctu; Plantival novo; Pronervon Phyto; Schlafund Nerventee; Schwedentrunk Elixier; Sedacur; Sedariston Konzentrat; Sedariston plus; Sedaselect D; Selon; Sensinerv forte; Tornix; Valdispert comp; Valeriana comp novum; Valeriana mild; Valverde Baldrian Hopfen bei Einschlafstorungen und zur Beruhigung; Vivinox Day. Hungary: Euvekan; Hova. India: Well-Beeing. Israel: Calmanervin; Calmanervin; Nerven-Dragees; Passiflora Compound; Passiflora; Songha Night. Italy: Anevrasi; Biocalm; Dormiplant; Fitosonno; Florelax; Glicero-Valerovit; Noctis; Parvisedil; Reve; Sedatol; Sedopuer F. Mexico: Nervinetas; Plantival. Portugal: Neurocardol; Songha; Valesono. Russia: Doppelherz Vitalotonik (Доппельгерц Виталотоник); Herbion Drops for the Heart (Гербион Сердечные Капли); Persen (Персен); Sanason (Санасон). South Africa: Avena Sativa Comp; Biral; Entressdruppels HM; Helmontskruie; Krampdruppels; Restin; Stuidruppels; Wonderkroonessens. Spain: Natusor Somnisedan; Nervikan; Relana; Sedasor; Sedonat; Valdispert Complex. Switzerland: Baldriparan; Dormeasan; Dormiplant; Dragees pour la detente nerveuse; Dragees pour le coeur et les nerfs; Dragees pour le sommeil; Dragees sedatives Dr Welti; Hova; Nervinetten; ReDormin; Relaxane; Relaxo; Songha Night; Soporin; Strath Gouttes pour le nerfs et contre l'insomnie; Tisane calmante pour les enfants; Tisane pour le sommeil et les nerfs; Valverde Coeur; Valverde Detente dragees; Valverde Sommeil; Valviska; Zeller Sommeil. UK: Avena Sativa Comp; Bio-Strath Valerian Formula; Boots Alternatives Sleep Well; Boots Sleepeaze Herbal Tablets; Calmanite Tablets; Constipation Tablets; Daily Tension & Strain Relief; Digestive; Fenneherb Newrelax; Fenneherb Prementaid; Gerard House Serenity; Gerard House Somnus; Golden Seal Indigestion Tablets; Herbal Indigestion Naturtabs; Herbal Pain Relief; HRI Calm Life; HRI Golden Seal Digestive; HRI Night; Indigestion and Flatulence; Kalms Sleep; Kalms; Laxative Tablets; Menopause Relief; Modern Herbals Stress; Napiers Digestion Tablets; Napiers Sleep Tablets; Napiers Tension Tablets; Natrasleep; Natural Herb Tablets; Nerfood Tablets; Nervous Dyspepsia Tablets; Newrelax; Nighttime Herb; Nodoff; Period Pain Relief; PMT Formula; Prementaid; Quiet Days; Quiet Life; Quiet Nite; Quiet Tyme; Relax Bþ; Roberts Alchemilla Compound Tablets; Scullcap & Gentian Tablets; Sominex Herbal; Stressless; SuNerven; SureLax (Herbal); Unwind Herbal Nytol; Valerina Day Time; Valerina Day-Time; Valerina Night-Time; Valerina NightTime; Vegetable Cough Remover; Wellwoman; Wind & Dyspepsia Relief. USA: Calming Aid; Stress Complex; StressEez. Venezuela: Cratex; Equaliv; Eufytose; Lupassin; Nervinetas; Pasidor; Pasifluidina; Rendetil.

References

1Upton R, ed. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and Therapeutic Compendium. Valerian root. Valeriana officinalis. Analytical, Quality

Control, and Therapeutic Monograph. Santa Cruz: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, 1999.

2 Houghton PJ. The biological activity of valerian and related plants. J Ethnopharmacol 1988; 22: 121–142.

3 Morazzoni P, Bombardelli E. Valeriana officinalis: traditional use and recent evaluation of activity. Fitoterapia 1995; 66: 99–112.

4 Houghton PJ. The scientific basis for the reputed activity of valerian. J Pharm Pharmacol 1999; 51: 505–512.

5 Houghton PJ, ed. Valerian. The genus Valeriana. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997.

6 Inouye H et al. [The absolute configuration of valerosidate and of didovaltrate]. Tetrahedron Lett 1974; 30: 2317–2325 [German].

7Pullela SV et al. New acylated clionasterol glycosides from Valeriana officinalis. Planta Med 2005; 71(10): 960–961.

8Bos R et al. Isolation and identification of valerenane sesquiterpenoids from Valeriana officinalis. Phytochemistry 1986; 25: 133–135.

9 Bos R et al. Isolation of the sesquiterpene alcohol ( )-pacifigorgiol from Valeriana officinalis. Phytochemistry 1986; 25: 1234–1235.

10Stoll A et al. New investigations on Valerian. Schweiz ApothekerZeitung 1957; 95: 115–120.

11Hendricks H et al. Eugenyl isovalerate and isoeugenyl isovalerate in the essential oil of Valerian root. Phytochemistry 1977; 16: 1853–1854.

12Lapke C et al. Free amino acids in commercial preparations of

Valeriana officinalis L. Pharm Pharmacol Lett 1997; 4: 172–174.

13Gao XQ, Björk L. Valerenic acid derivatives and valepotriates among individuals, varieties and species of Valeriana. Fitoterapia 2000; 71: 19–24.

14Leathwood PD et al. Aqueous extract of valerian root improves sleep quality in man. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1982; 17: 65–71.

15Schulz H et al. The effect of valerian extract on sleep polygraphy in poor sleepers: a pilot study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1994; 27: 147–151.

16Hendricks H et al. Pharmacological screening of valerenal and some other components of essential oil of Valeriana officinalis. Planta Med 1981; 42: 62–68.

17Wagner H et al. Comparative studies on the sedative action of Valeriana extracts, valepotriates and their degradation products. Planta Med 1980; 39: 358–365.

18Hendriks H et al. Central nervous depressant activity of valerenic acid in the mouse. Planta Med 1985; 51: 28–31.

19Riedel E et al. Inhibition of g-aminobutyric acid catabolism by valerenic acid derivatives. Planta Med 1982; 48: 219–220.

20Santos MS et al. The amount of GABA present in aqueous extracts of valerian is sufficient to account for [3H]GABA release in synaptosomes. Planta Med 1994; 60: 475–476.

21Santos MS et al. Synaptosomal GABA release as influenced by valerian root extract – involvement of the GABA carrier. Arch Int Pharmacodyn 1994; 327: 220–231.

22Santos MS et al. An aqueous extract of valerian influences the transport of GABA in synaptosomes. Planta Med 1994; 60: 278–279.

23Cavadas C et al. In vitro study on the interaction of Valeriana

officinalis L. extracts and their amino acids on GABAA receptor in rat brain. Arzneimittelforschung/Drug Res 1995; 45: 753–755.

24Mennini T et al. In vitro study on the interaction of extracts and pure compounds from Valeriana officinalis roots with GABA, benzodiazepine and barbiturate receptors in the brain. Fitoterapia 1993; 64: 291–300.

25Ortiz JG et al. Effects of Valeriana officinalis extracts on [3H] flunitrazepam binding, synaptosomal [3H]GABA uptake, and hippocampal [3H]GABA release. Neurochem Res 1999; 24: 1373– 1378.

26Dietz BM et al. Valerian extract and valerenic acid are partial agonists

of the 5-HT5a receptor in vitro. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2005; 138(2): 191–197.

27Abourashed EA et al. In vitro binding experiments with a valerian, hops and their fixed combination extract (Ze91019) to selected central nervous system receptors. Phytomedicine 2004; 11: 633–638.

28Veith J et al. The influence of some degradation products of valepotriates on the motor activity of light-dark synchronized mice. Planta Med 1986; 52: 179–183.

Valerian 589

29Andreatini R, Leite JR. Effect of valepotriates on the behavior of rats in the elevated plus-maze during diazepam withdrawal. Eur J Pharmacol 1994; 260: 233–235.

30Petkov V. Plants with hypotensive, antiatheromatous and coronarodilating action. Am J Chin Med 1979; 7: 197–236.

31Petkov V, Manolav P. To the pharmacology of iridoids. Paper presented at the 2nd Congress of the Bulgarian Society for Physiological Sciences, Sofia, October 31–November 3, 1974.

32Hazelhoff B et al. Antispasmodic effects of Valeriana compounds: an in vivo and in vitro study on the guinea-pig ileum. Arch Int Pharmacodyn 1982; 257: 274–287.

33Pilcher JD et al. The action of so-called female remedies on the excised uterus of the guinea-pig. Arch Intern Med 1916; 18: 557–583.

34Pilcher JD, Mauer RT. The action of female remedies on the intact uteri of animals. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1918; 97–99.

35Van Meer JH. Plantaardige stoffen met een effect op het complementsysteem. Pharm Weekbl 1984; 119: 836–942.

36Bounthanh C et al. The action of valepotriates on the synthesis of DNA and proteins of cultured hepatoma cells. Planta Med 1983; 49: 138–142.

37Bounthanh C et al. Valepotriates, a new class of cytotoxic and antitumour agents. Planta Med 1981; 41: 21–28.

38Braun R et al. Influence of valtrate/isovaltrate on the hematopoiesis and metabolic liver activity in mice in vivo. Planta Med 1984; 50: 1–4.

39Hude W et al. Bacterial mutagenicity of the tranquillizing constituents of Valerianaceae roots. Mutat Res 1986; 169: 23–27.

40Anderson GD et al. Pharmacokinetics of valerenic acid after administration of valerian in healthy subjects. Phytotherapy Research 2005; 19(9): 801–803.

41Leathwood PD, Chauffard F. Quantifying the effects of mild sedatives. J Psychiatr Res 1983; 17: 115–122.

42Donath F et al. Critical evaluation of the effect of valerian extract on sleep structure and sleep quality. Pharmacopsychiatry 2000; 33: 47–53.

43Vorbach EU et al. Therapie von Insomnien. Wirksamkeit und Verträglichkeit eines Baldrianpräparats. Psychopharmakotherapie 1996; 3: 109–115.

44Diaper A, Hindmarch I. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of two doses of a valerian preparation on the sleep, cognitive and psychomotor function of sleep-disturbed older adults. Phytother Res 2004; 18: 831–836.

45Kamm-Kohl AV et al. Moderne Baldriantherapie gegen nervöse Störungen im Senium. Med Welt 1984; 35: 1450–1454.

46Leathwood PD, Chauffard F. Aqueous extract of valerian reduces latency to fall asleep in man. Planta Med 1985; 51: 144–148.

47Coxeter PD et al. Valerian does not appear to reduce symptoms for patients with chronic insomnia in general practice using a series of randomised n-of-1 trials. Complement Ther Med 2003; 11(4): 215– 222.

48Jacobs BP et al. An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia. Medicine 2005; 84 (4): 197–207.

49Dorn M. [Baldrian versus oxazepam: efficacy and tolerability in nonorganic and non-psychiatric insomniacs. A randomised, double-blind, clinical, comparative study]. Forsch Komplement Klass Naturheilkd

2000; 7: 79–84.

50Schmitz M, Jäckel M. [Comparative study investigating the quality of life in patients with environmental sleep disorders (temporary

dyscoimesis and dysphylaxia) under therapy with a hop-valerian |

V |

preparation and a benzodiazepine preparation.] Wiener Med |

|

Wochenschrift 1998; 148: 291–298 [German]. |

51Stevinson C, Ernst E. Valerian for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Sleep Med 2000; 1: 91–99.

52Morin CM et al. Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep 2005; 28(11): 1465–1471.

53Muller-Limmroth W, Ehrenstein W. Untersuchungen über die Wirkung von Seda-Kneipp auf den Schlaf schlafgëstorter Menschen. Med Klin 1977; 72: 1119–1125.

54Cerny A, Schmid K. Tolerability and efficacy of valerian/lemon balm in healthy volunteers (a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study). Fitoterapia 1999; 70: 221–228.

590 |

Valerian |

|

|

|

55 |

Dressing H et al. Verbesserung der Schlafqualität mit einem |

69 |

Garges HP et al. Cardiac complications and delirium associated with |

|

|

hochdosierten Baldrian-Melisse-Präparat. Eine plazebokontrollierte |

|

valerian root withdrawal. JAMA 1998; 280: 1566–1567. |

|

|

Doppelblindstudie. Psychopharmakotherapie 1996; 3: 123–130. |

70 |

MacGregor FB et al. Hepatotoxicity of herbal medicines. BMJ 1989; |

|

56 |

Dressing H et al. Baldrian-Melisse-Kombinationen versus |

|

299: 1156–1157. |

|

|

Benzodiazepin. Bei Schlafstörungen gleichwertig? Therapiewoche |

71 |

Shaw D et al. Traditional remedies and food supplements. A five-year |

|

|

1992; 42: 726–736. |

|

toxicological study (1991–1995). Drug Safety 1997; 17: 342–356. |

|

57 |

Vonderheid-Guth B et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of valerian and |

72 |

Willey LB et al. Valerian overdose: a case report. Vet Human Toxicol |

|

|

hops extract combination (ZE-91019) on the quantitative- |

|

1995; 37: 364–365. |

|

|

topographical EEG in healthy volunteers. Eur J Med Res 2000; 5: 139– |

73 |

Chan TYK et al. Poisoning due to an over-the-counter hypnotic, |

|

|

144. |

|

|

Sleep-Qik (hyoscine, cyproheptadine, valerian). Postgrad Med J 1995; |

58 |

Schellenberg R et al. The fixed combination of valerian and hops |

|

71: 227–228. |

|

|

(Ze91019) acts via a central adenosine mechanism. Planta Med 2004; |

74 |

Chan TYK. An assessment of the delayed effects associated with |

|

|

70(7): 594–597. |

|

valerian overdose. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1998; 36: 569. |

|

59 |

Francis AJP, Dempster RJW. Effect of valerian, Valeriana edulis, on |

75 |

Hallam KT et al. Comparative cognitive and psychomotor effects of |

|

|

sleep difficulties in children with intellectual deficits: randomised trial. |

|

single doses of Valeriana officinalis and triazolam in healthy |

|

|

Phytomedicine 2002; 9: 273–279. |

|

volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp 2003; 18: 619–625. |

|

60 |

Poyares DR et al. Can valerian improve the sleep of insomniacs after |

76 |

Gutierrez S et al. Assessing subjective and psychomotor effects of the |

|

|

benzodiazepine withdrawal? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psych |

|

herbal medication valerian in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem |

|

|

2002; 26: 539–545. |

|

Behav 2004; 78: 57–64. |

|

61 |

Andreatini R et al. Effect of valepotriates (valerian extract) in |

77 |

Glass JR et al. Acute pharmacological effects of temazepam, |

|

|

generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot |

|

diphenhydramine, and valerian in healthy elderly subjects. J Clin |

|

|

study. Phytotherapy Res 2002; 16: 650–654. |

|

Psychopharmacol 2003; 23: 260–268. |

|

62 |

Cropley M et al. Effect of kava and valerian on human physiological |

78 |

Gerhard U et al. [Effects of two plant-based sleep remedies on |

|

|

and psychological responses to mental stress assessed under |

|

vigilance]. Schweiz Runsch Med Prax 1996; 85: 473–481 [German]. |

|

|

laboratory conditions. Phytotherapy Res 2002; 16: 23–27. |

79 |

Vo LT et al. Investigation of the effects of peppermint oil and valerian |

|

63 |

Kohnen R, Oswald W-D. The effects of valerian, propranolol, and |

|

on rat liver and cultured human liver cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol |

|

|

their combination on activation, performance, and mood of healthy |

|

Physiol 2003; 30: 799–804. |

|

|

volunteers under social stress conditions. Pharmacopsychiatry 1988; |

80 |

Tufik S et al. Effects of a prolonged administration of valepotriates in |

|

|

21: 447–448. |

|

rats on the mothers and their offspring. J Ethnopharmacol 1994; 41: |

|

64 |

Panijel M. Die behandlung mittelschwerer angstzustände. |

|

39–44. |

|

|

Therapiewoche 1985; 41: 4659–4668. |

81 |

Donovan JL et al. Multiple night-time doses of valerian (Valeriana |

|

65 |

Kneibel R, Burchard JM. Zur Therapie depressiver Verstimmungen in |

|

officinalis) had minimal effects on CYP3A4 activity and no effect on |

|

|

der Praxis. Z Allgemeinmed 1988; 64: 689–696. |

|

CYP2D6 activity in healthy volunteers. Drug Metab Disp 2004; 32 |

|

66 |

Steger W. Depressive Verstimmungen. Z Allgemeinmed 1985; 61: 914– |

|

(12): 1333–1336. |

|

|

918. |

|

82 |

Gurley BJ et al. In vivo effects of goldenseal, kava kava, black cohosh, |

67 |

Linde K et al. St John's wort for depression – an overview and meta- |

|

and valerian on human cytochrome P450 1A2, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4/5 |

|

|

analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 1996; 313: 253–258. |

|

phenotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005; 77: 415–426. |

|

68 |

Kuhlmann J et al. The influence of valerian treatment on 'reaction |

83 |

Lefebvre T et al. In vitro activity of commercial valerian extracts |

|

|

time, alertness and concentration' in volunteers. Pharmacopsychiatry |

|

against human cytochrome P450 3A4. J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 2004; 7 |

|

|

1999; 32: 235–241. |

|

(2): 265–273. |

|

V