- •Contents

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •About the Authors

- •How to Use Herbal Medicines

- •Introduction

- •General References

- •Agnus Castus

- •Agrimony

- •Alfalfa

- •Aloe Vera

- •Aloes

- •Angelica

- •Aniseed

- •Apricot

- •Arnica

- •Artichoke

- •Asafoetida

- •Avens

- •Bayberry

- •Bilberry

- •Bloodroot

- •Blue Flag

- •Bogbean

- •Boldo

- •Boneset

- •Borage

- •Broom

- •Buchu

- •Burdock

- •Burnet

- •Butterbur

- •Calamus

- •Calendula

- •Capsicum

- •Cascara

- •Cassia

- •Cat’s Claw

- •Celandine, Greater

- •Celery

- •Centaury

- •Cereus

- •Chamomile, German

- •Chamomile, Roman

- •Chaparral

- •Cinnamon

- •Clivers

- •Clove

- •Cohosh, Black

- •Cohosh, Blue

- •Cola

- •Coltsfoot

- •Comfrey

- •Corn Silk

- •Couchgrass

- •Cowslip

- •Cranberry

- •Damiana

- •Dandelion

- •Devil’s Claw

- •Drosera

- •Echinacea

- •Elder

- •Elecampane

- •Ephedra

- •Eucalyptus

- •Euphorbia

- •Evening Primrose

- •Eyebright

- •False Unicorn

- •Fenugreek

- •Feverfew

- •Figwort

- •Frangula

- •Fucus

- •Fumitory

- •Garlic

- •Gentian

- •Ginger

- •Ginkgo

- •Ginseng, Eleutherococcus

- •Ginseng, Panax

- •Golden Seal

- •Gravel Root

- •Ground Ivy

- •Guaiacum

- •Hawthorn

- •Holy Thistle

- •Hops

- •Horehound, Black

- •Horehound, White

- •Horse-chestnut

- •Horseradish

- •Hydrangea

- •Hydrocotyle

- •Ispaghula

- •Jamaica Dogwood

- •Java Tea

- •Juniper

- •Kava

- •Lady’s Slipper

- •Lemon Verbena

- •Liferoot

- •Lime Flower

- •Liquorice

- •Lobelia

- •Marshmallow

- •Meadowsweet

- •Melissa

- •Milk Thistle

- •Mistletoe

- •Motherwort

- •Myrrh

- •Nettle

- •Parsley

- •Parsley Piert

- •Passionflower

- •Pennyroyal

- •Pilewort

- •Plantain

- •Pleurisy Root

- •Pokeroot

- •Poplar

- •Prickly Ash, Northern

- •Prickly Ash, Southern

- •Pulsatilla

- •Quassia

- •Queen’s Delight

- •Raspberry

- •Red Clover

- •Rhodiola

- •Rhubarb

- •Rosemary

- •Sage

- •Sarsaparilla

- •Sassafras

- •Saw Palmetto

- •Scullcap

- •Senega

- •Senna

- •Shepherd’s Purse

- •Skunk Cabbage

- •Slippery Elm

- •Squill

- •St John’s Wort

- •Stone Root

- •Tansy

- •Thyme

- •Uva-Ursi

- •Valerian

- •Vervain

- •Wild Carrot

- •Wild Lettuce

- •Willow

- •Witch Hazel

- •Yarrow

- •Yellow Dock

- •Yucca

- •1 Potential Drug–Herb Interactions

- •4 Preparations Directory

- •5 Suppliers Directory

- •Index

Jamaica Dogwood

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

Jamaica dogwood is characterised by various isoflavone constituents, to which the antispasmodic properties described for the wood have been attributed. In addition, sedative and narcotic activities have been documented following preclinical studies, thus supporting the reputed herbal uses. However, there is a lack of clinical research assessing the efficacy and safety of Jamaica dogwood. Although Jamaica dogwood is reported to be of low toxicity

in various animal species, it is also documented as toxic to humans.(G51) In view of this, excessive use of Jamaica

dogwood and use during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Species (Family)

Piscidia piscipula L. Sarg. (Leguminosae)

Synonym(s)

Erythina piscipula L., Fish Poison Bark, Ichthyomethia communis

S.F. Blake, I. piscipula (L.) Hitchc., I. piscipula (L.) Hitchc., var. typica Stehle & L. Quentin, P. inebrians Medik, P. erythina L., P. toxicaria Salisb., Robinia alata Mill., West Indian Dogwood

Part(s) Used

Root bark

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHC 1992(G6)

BHP 1996(G9)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL(G37)

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General References G6 and G40.

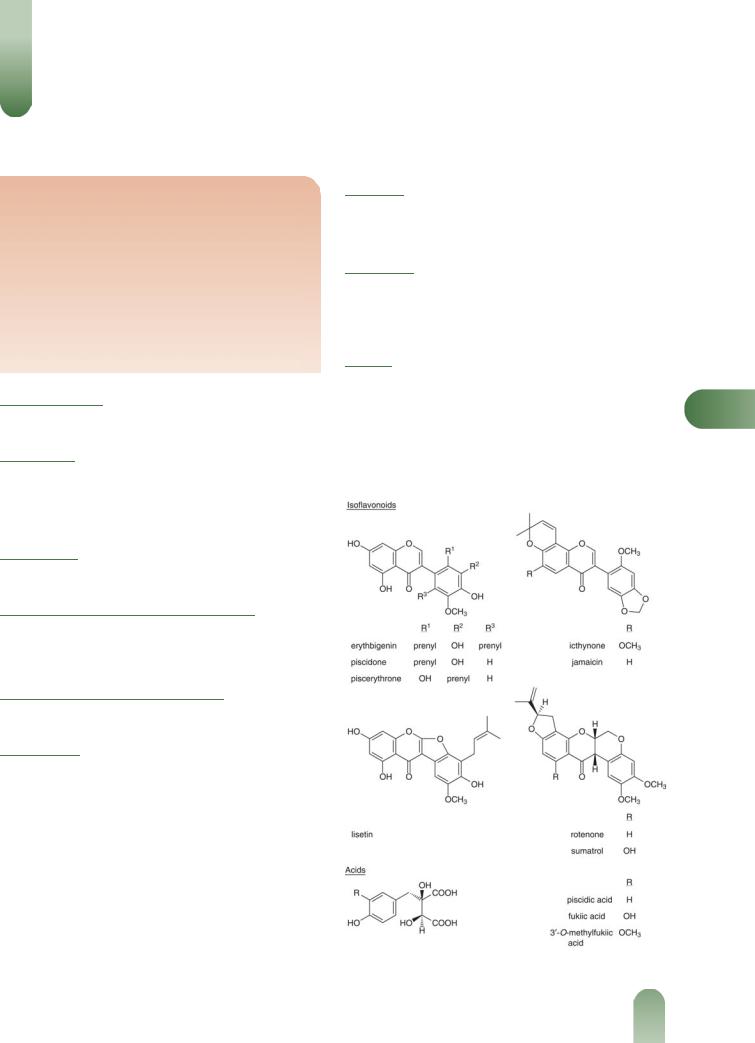

Acids Piscidic acid (p-hydroxybenzyltartaric) and its mono and diethyl esters,(1) fukiic acid and the 30-O-methyl derivative; malic acid, succinic acid, and tartaric acid.

Isoflavonoids Ichthynone, jamaicin, piscerythrone, piscidone and others. Milletone, isomillettone, dehydromillettone, rotenone and sumatrol (rotenoids), and lisetin.(2–5)

Glycosides Piscidin, reported to be a mixture of two compounds, saponin glycoside (unidentified).(6)

Other constituents Alkaloid (unidentified, reported to be from

the stem), resin, volatile oil 0.01%, b-sitosterol, tannin (unspecified).(6)

Food Use

Jamaica dogwood is stated by the Council of Europe to to be

toxicologically unacceptable for use as a natural food flavour-

ing.(G16)

Herbal Use

Jamaica dogwood is stated to possess sedative and anodyne properties. Traditionally, it has been used for neuralgia, migraine,

insomnia, dysmenorrhoea, and specifically for insomnia due to neuralgia or nervous tension.(G6, G7, G8, G64)

Dosage

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses |

|

||

recommended in older and contemporary standard herbal and/or |

J |

||

pharmaceutical reference texts are given below. |

|||

Dried root bark |

1–2 g as a decoction three times daily.(G6, G7) |

||

Liquid extract |

1–2 mL |

(1 : 1 in 30% alcohol) three times |

|

daily.(G6, G7) |

|

|

|

Liquid Extract of Piscidia |

(BPC 1934) 2–8 mL. |

|

|

Figure 1 Selected constituents of Jamaica dogwood.

379

380 Jamaica Dogwood

Figure 2 Jamaica dogwood (Piscidia piscipula).

J

Figure 3 Jamaica dogwood – dried drug substance (root bark).

Pharmacological Actions

In vitro and animal studies

Results of early studies reported Jamaica dogwood to possess weak cannabinoid and sedative activities in the mouse, guinea-pig and cat.(6–8) In addition, in vitro antispasmodic activity on rabbit intestine, and guinea-pig and rat uterine muscle(6, 9, 10) were noted and in vivo utero-activity in the cat and monkey were documented.(6, 7, 10, 11) In some instances, in vitro antispasmodic activity was found to be comparable to, or greater than, that observed for papaverine.

More recent work has supported these findings and reported that the antispasmodic activity of Jamaica dogwood on uterine smooth muscle is attributable to two isoflavone constituents, one being equipotent to papaverine.(11)

Jamaica dogwood extracts have also been documented to exhibit antitussive, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory activities in various experimental animals.(7)

Rotenone is an insecticide that has been used in agriculture for the control of lice, fleas, and as a larvicide.(G45) Jamaica dogwood has been used extensively throughout Central and South America as a fish poison;(6) the wood contains two piscicidal principles, rotenone and ichthynone.

Rotenone has reportedly exhibited anticancer activity towards lymphocytic leukaemia and human epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx.(G22)

Clinical studies

There is a lack of clinical research assessing the effects of Jamaica dogwood and rigorous randomised controlled clinical trials are required.

Side-effects, Toxicity

There is a lack of clinical safety and toxicity data for Jamaica dogwood and further investigation of these aspects is required.

Symptoms of overdose are stated to include numbness, tremors, salivation and sweating.(G22)

Jamaica dogwood has been found to be toxic when administered parenterally to rats and rabbits, but non-toxic when given orally, with doses exceeding 90 g dried extract/kg tolerated.(6) An LD50 (mice, intravenous injection) of an unidentified saponin constituent has been reported as 75 mg/kg body weight.(9) Oral doses of up to 1.5 mg/kg were stated to have no effect.(6)

Jamaica dogwood is stated to be irritant and toxic to humans.(G51) Rotenone is documented to be carcinogenic.(G22)

Contra-indications, Warnings

None documented. However, in view of the available information, Jamaica dogwood should be used with caution.

Drug interactions None documented. However, the potential for preparations of Jamaica dogwood to interact with other medicines administered concurrently, particularly those with similar or opposing effects, should be considered. There is limited evidence from preclinical studies that Jamaica dogwood has sedative activity.

Pregnancy and lactation Jamaica dogwood has been reported to exhibit a potent depressant action on the uterus both in vitro and in vivo. In view of this and the general warnings regarding the use of Jamaica dogwood, it should not be used during pregnancy and lactation.

References

1 Bridge W et al. Constituents of 'Cortex Piscidiae Erythrinae'. Part I. The structure of piscidic acid. J Chem Soc 1948; 257.

2Falshaw CP et al. The Extractives of Piscidia Erythrina L. III. The constitutions of lisetin, piscidone and piscerythrone. Tetrahedron

1966; Suppl 7: 333–348.

3Redaelli C, Santaniello E. Major isoflavonoids of the Jamaican dogwood Piscidia erythrina. Phytochemistry 1984; 23: 2976–2977.

4Delle Monache F et al. Two isoflavones from Piscidia erythrina. Phytochemistry 1984; 23: 2945–2947.

5 Harborne JB, Mabry TJ, eds. The Flavonoids. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1982: 606.

6Costello CH, Butler CL. An investigation of Piscidia erythrina (Jamaica Dogwood). J Am Pharm Assoc 1948; 37: 89–96.

7Aurousseau M et al. Certain pharmacodynamic properties of Piscidia erythrina. Ann Pharm Fr 1965; 23: 251–257.

8Della-Loggia R et al. Evaluation of the activity on the mouse CNS of several plant extracts and a combination of them. Riv-Neurol 1981;

51: 297–310.

9 Pilcher JD et al. The action of the so-called female remedies on the excised uterus of the guinea-pig. Arch Intern Med 1916; 18: 557–583.

10Pilcher JD, Mauer RT. The action of female remedies on the intact uteri of animals. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1918; 97–99.

11Della Loggia R et al. Isoflavones as spasmolytic principles of Piscidia erythrina. Prog Clin Biol Res 1988; 280: 365–368.

Java Tea

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

The reported pharmacological activities of Java tea are mainly associated with the lipophilic flavonoids, benzochromene and, to a lesser extent, diterpene constituents.

Documented scientific evidence from in vitro and animal studies provides some supportive evidence for some of the traditional uses of Java tea. However, there is a lack of clinical data and well-designed, controlled clinical trials involving adequate numbers of patients are required. Furthermore, studies investigating the active principles responsible for specific pharmacological activities and their mechanisms of action are necessary.

There have been reports of adulteration/botanical substitution occurring with Orthosiphon.(G2)

In view of the lack of toxicity and safety data, excessive use of Java tea, and use during pregnancy and lactation, should be avoided.

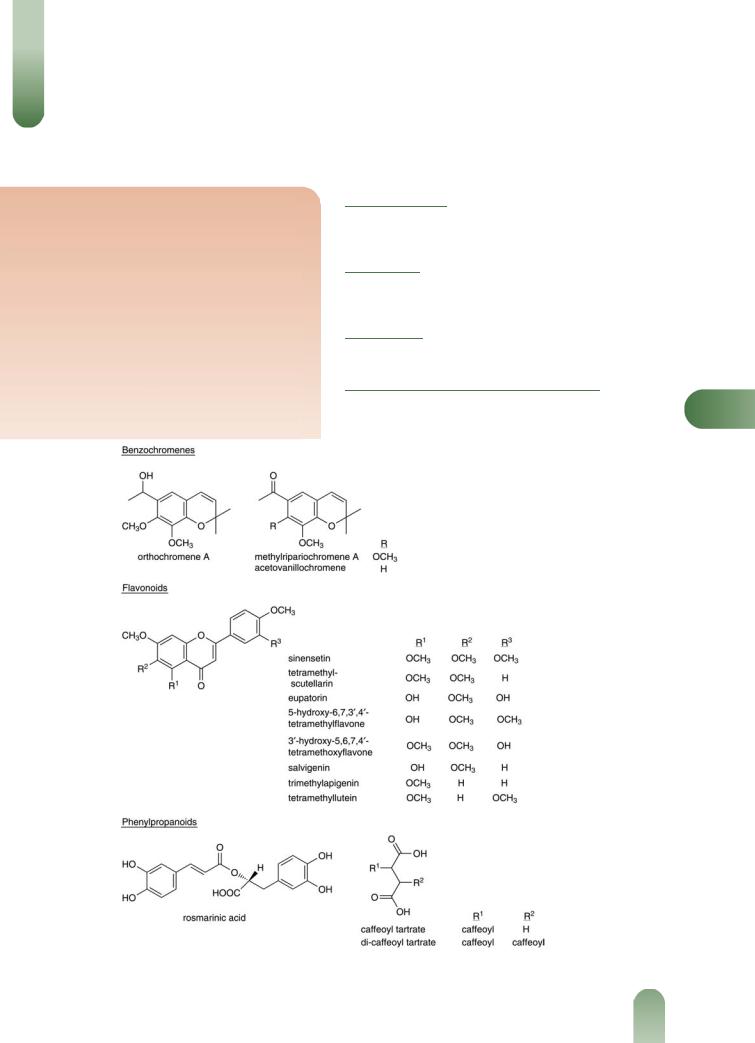

Figure 1 Selected constituents of java tea.

Species (Family)

Orthosiphon aristatus var. aristatus (Blume) Miq. (Labiatae/ Lamiaceae)

Synonym(s)

Kumis Kucing (Indonesian, Malay), Orthosiphon aristatus Miq.,

Orthosiphon spicatus (Thunb.) Bak., O. stamineus Benth.

Part(s) Used

Fragmented dried leaves, tops of stems

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHP 1996(G9)

BP 2007(G84) J

Complete German Commission E(G3)

381

382 Java Tea

ESCOP 2003(G76)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

Ph Eur 2007(G81)

Legal category (Licensed Products)

Java tea is not included in the GSL.

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General References G2 and G52.

Benzochromenes Orthochromene A,(1) methylripariochromene A(2) and acetovanillochromene.(1, 3)

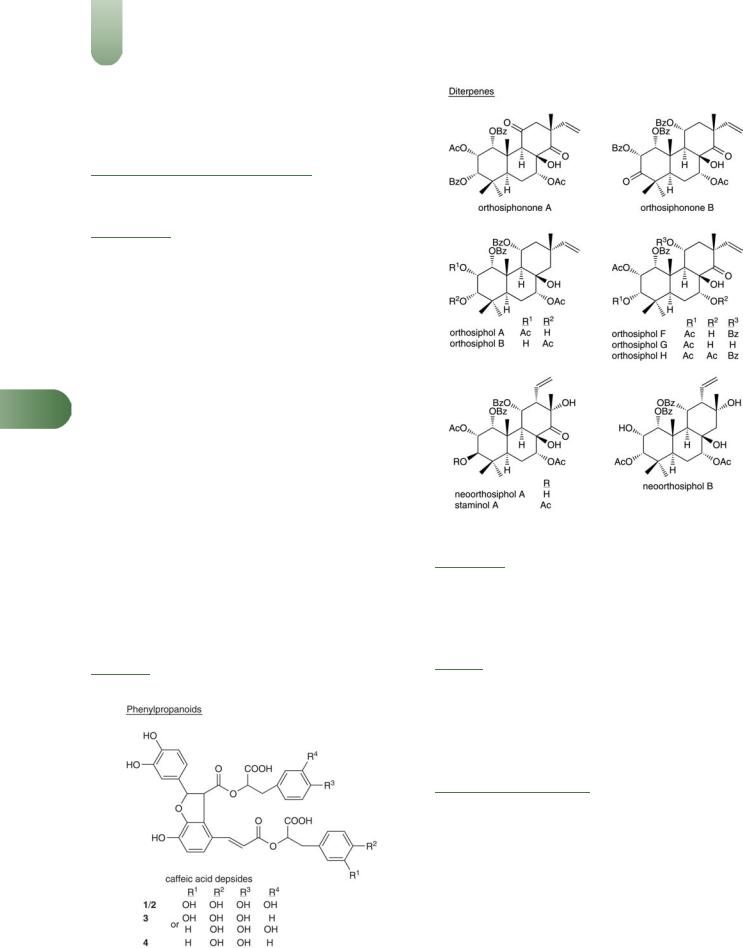

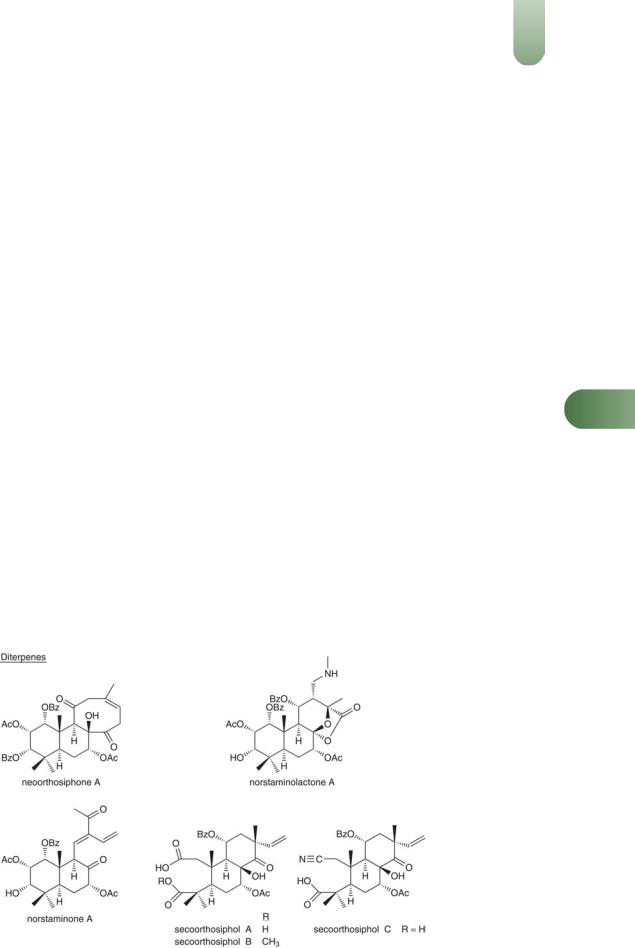

Diterpenes Numerous closely related pimarane-type diterpenes,

including orthosiphonones A and B,(1) orthosiphols A, B, E to I, M, N, P, R, S, T,(4, 5) staminol A(5) neo-orthosiphols A and B(3, 6, 7)

neo-orthosiphone A,(8) norstaminolactone A, norstaminols B and C, norstaminone A,(7) and seco-orthosiphols A to C.(9)

Jelemene, b-caryophyllene, a-humulene, b-caryophyllene oxide, can-2-one and palmitic acid.(10)

Flavonoids Sinensetin, tetramethylscutellarein, eupatorin, 5- hydroxy-6,7,30,40-tetramethoxyflavone, 30-hydroxy-5,6,7,40-tetra-

methoxyflavone, salvigenin, trimethylapigenin, tetramethoxylute- olin(11) nine flavonoids which are methylated derivatives ofEssential oil 0.02–0.7%. Various compounds including b-

scutellarein (5,6,7,40-tetramethoxyflavone) or 6-hydroxyluteolin (5,6,7, 30,40-pentahydroxyflavone), quercetin-3-O-glucoside, kaempferol-3-O-glucoside,(3, 12–15) 40,5,6,7-tetramethoxyflavone, 30,40,5,6,7-pentamethoxyflavone.(16)

Phenylpropanoids Rosmarinic acid (major), caffeoyl tartrate, dicaffeoyltartrate, four caffeic acid depsides (1–4).(13)

Other constituents Inositol, phytosterols (e.g. b-sitosterol),(11, 13) esculetin (a coumarin), potassium salts.

Food Use

Java tea is not used in foods.

Figure 2 Selected constituents of java tea.

Figure 3 Selected constituents of java tea.

Herbal Use

Java tea has traditionally been used in Java for the treatment of hypertension and diabetes.(1, 6, 17, G35) It has also been used in folk

medicine for bladder and kidney disorders, gallstones, gout and rheumatism. Java tea is stated to have diuretic properties.(18)

Dosage

Dosage for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses recommended in contemporary standard herbal reference texts are given below.

Dried material 2–3 g in 150 mL water two to three times daily as an infusion.(G52)

Pharmacological Actions

In vitro and animal studies

Diuretic effects Several studies in rats have reported diuretic activity of extracts of O. stamineus and O. aristatus(18–20) and of

flavonoids (sinensetin and a tetramethoxyflavone) isolated from O. aristatus.(21) Intraperitoneal administration of a hydroalcoholic extract of O. stamineus to rats caused a significant diuresis over the following 2–24 hours compared with controls.(18) The effect was similar to that observed following intraperitoneal administration of hydrochlorothiazide (10 mg/kg).(18) Oral administration of an aqueous extract of O. aristatus increased ion excretion to a similar extent as did furosemide, although no diuretic action was noted.(20)

|

|

Java Tea |

383 |

|

|

Oral administration of methylripariochromene A (100 mg/kg) |

been reported to exhibit a suppressive effect on contractile |

|

|||

has been shown to increase urinary volume in fasted rats for three |

responses in the rat thoracic aorta.(3) |

|

|

||

hours after oral administration; the increase in urine volume was |

Cytostatic effects Sinensetin and tetramethylscutellarein |

have |

|

||

similar to that observed with oral administration of hydrochloro- |

|

||||

thiazide (25 mg/kg).(17) |

Sodium, potassium and chloride ion |

been reported to demonstrate in vitro cytostatic activity towards |

|

||

excretion was increased with methylripariochromene A (100 mg/ |

Ehrlich ascites tumour cells.(23) Growth inhibition appears to be |

|

|||

kg), although urinary sodium ion excretion did not increase. A |

dose dependent, with 50% inhibition occurring at concentrations |

|

|||

mechanism for the diuretic action of methylripariochromene A |

of approximately 30 and 15 mg/mL for sinensetin and tetra- |

|

|||

has not yet been elucidated, although it appears to have a different |

methylscutellarein, respectively. Orthosiphols A and B have been |

|

|||

mode of action to that of hydrochlorothiazide.(17) |

reported to inhibit inflammation induced by the tumour promoter |

|

|||

|

In normoglycaemic rats, oral adminis- |

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) on mouse ears.(4) |

|

||

Hypoglycaemic effects |

Fractions of O. stamineus leaves have been reported to have |

|

|||

tration of an aqueous extract of O. stamineus (0.5 g/kg) had no |

activity against a melanoma cell line in vitro.(24) |

|

|

||

significant effect on fasting blood glucose concentrations over a 7- |

Antimicrobial effects An aqueous extract of O. aristatus has |

|

|||

hour period, although |

administration of 1 g/kg produced a |

|

|||

significant decrease in blood glucose concentration compared |

demonstrated antibacterial activity against two serotypes of |

|

|||

with that in a control group.(22) A hypoglycaemic effect was also |

Streptococcus mutans (MIC 7.8–23.4 mg/mL).(25) Other in vitro |

|

|||

observed following administration of O. stamineus extract (1 g/kg) |

studies have reported a lack of antibacterial activity for flavonoids |

|

|||

to rats loaded with glucose (1.5 g/kg) and in streptozotocin- |

(sinensetin, tetramethylscutellarein and a tetramethoxyflavone in |

|

|||

induced diabetic rats; the effect of O. stamineus extract in |

concentrations of 10 and 100 mg/mL) isolated from O. aristatus |

|

|||

streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats was similar to that observed |

leaves against Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas |

|

|||

with glibenclamide (10 mg/kg).(22) |

aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus.(21) |

|

|

||

Antihypertensive effects Methylripariochromene A has been |

O. stamineus extract has also been shown to inhibit spore |

J |

|||

germination in six out of nine fungal species tested: Sacchar- |

|||||

reported to have several pharmacological actions related to |

omyces pastorianus, Candida albicans, Rhizopus nigricans, |

||||

|

|||||

antihypertensive activity. |

|

Penicillium digitatum, Fusarium oxysporum and Trichophyton |

|

||

In stroke-prone, spontaneously hypertensive rats, subcutaneous |

mentagrophytes.(26) |

|

|

||

administration of methylripariochromene A (100 mg/kg) produced |

|

|

|

||

a continuous reduction in systolic blood pressure and a decrease in |

Other effects In vitro, O. spicatus has been shown to inhibit 15- |

|

|||

heart rate. Methylripariochromene A also suppressed agonist- |

lipoxygenase, an enzyme thought to be involved in the develop- |

|

|||

induced contractions in the rat thoracic aorta and decreased the |

ment of atherosclerosis.(11) Furthermore, the flavonoids sinensetin |

|

|||

contractile force in isolated guinea-pig atria without significantly |

and tetramethylscutellarein demonstrate dose-dependent inhibi- |

|

|||

affecting the beating (heart) rate. The mechanism of action for |

tion with IC50 values of 114 5 and 110 3 mmol/L, respectively, |

|

|||

these antihypertensive effects of methylripariochromene A is, |

although other flavonoids from O. spicatus appear to be less |

|

|||

however, unclear.(17) |

|

efficient inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase. The inhibitory activity of |

|

||

Migrated pimarane-type diterpenes (neo-orthosiphols A and |

the whole extract was greater than could be expected from the |

|

|||

B), isopimarane-type diterpenes (orthosiphols A and B, orthosi- |

activities of each of its flavonoid constituents, and it has been |

|

|||

phonones A and B), benzochromenes (methylripariochromene, |

suggested that synergism may be occurring.(11) More recent in |

|

|||

acetovanillochromene, orthochromene A) and flavones (tetra- |

vitro studies have shown that flavonoids from O. spicatus prevent |

|

|||

methylscutellarein, sinensetin) isolated from O. aristatus have |

oxidative inactivation of 15-lipoxygenase, with trimethylapigenin, |

|

|||

Figure 4 Selected constituents of java tea.

|

384 |

Java Tea |

||

|

eupatorin and tetramethylluteolin showing the strongest enzyme- |

|||

|

stabilising effects.(27) However, there was no correlation between |

|||

|

enzyme stabilisation and enzyme inhibition.(27) |

|||

|

Clinical studies |

|||

|

Clinical investigation of preparations of Java tea is extremely |

|||

|

limited. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross- |

|||

|

over study reported no effect on 12and 24-hour urine output or |

|||

|

on sodium excretion in 40 healthy volunteers who received 600 mL |

|||

|

of an infusion of Orthosiphon leaves daily (equivalent to 10 g |

|||

|

dried leaves) for four days.(28) A small number of uncontrolled |

|||

|

studies has explored the effects of preparations of Java tea and |

|||

|

reported conflicting findings. The design of such studies does not |

|||

|

allow the observed effects to be attributed definitively to the |

|||

|

intervention. A study involving six healthy volunteers who drank |

|||

|

Orthosiphon tea (250 mL) every six hours for one day reported an |

|||

|

increase in urine acidity six hours after ingestion.(29) |

|||

|

A study involving 67 patients with uratic diathesis who received |

|||

|

Java tea for three months reported that no effects were observed |

|||

|

on diuresis, glomerular filtration, osmotic concentration, urinary |

|||

|

pH, plasma content and excretion of calcium, inorganic |

|||

J |

phosphorus and uric acid.(30) |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Side-effects, Toxicity |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

None documented. |

|||

|

Contra-indications, Warnings |

|

||

|

None known. In view of the lack of clinical data on the use of Java |

|||

|

tea, excessive or long-term use should be avoided. It has been |

|||

|

recommended that adequate fluid intake (2 L or more per day) |

|||

|

should be ensured whilst using Java tea,(G35) although the |

|||

|

scientific basis for this statement is not clear. |

|||

|

Drug interactions None documented. However, in view of the |

|||

|

documented pharmacological actions of Java tea, the potential for |

|||

|

preparations of Java tea to interfere with other medicines |

|||

|

administered concurrently, particularly those with similar or |

|||

|

opposing effects, should be considered. |

|||

|

Pregnancy and lactation There are no data available on the use |

|||

|

of Java tea in pregnancy and lactation. In view of the lack of |

|||

|

toxicity data, use of Java tea during pregnancy and lactation |

|||

|

should be avoided. |

|||

|

Preparations |

|||

|

Proprietary single-ingredient preparations |

|||

|

Germany: Carito mono; Diurevit Mono; Nephronorm med; |

|||

|

Orthosiphonblatter Indischer Nierentee; Repha Orphon. |

|||

|

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations |

|||

|

Austria: |

Solubitrat. France: Dellova; Tealine. Germany: |

||

|

Aqualibra; BioCyst; Canephron novo; Dr. Scheffler Bergischer |

|||

|

Krautertee Blasenund Nierentee; Harntee STADA; Harntee- |

|||

Steiner; Hevert-Blasen-Nieren-Tee N; Heweberberol-Tee; Nephronorm med; Nephrubin-N; Nephrubin-N. Spain: Lepisor; Urisor. Switzerland: Bilifuge; Demonatur Dragees pour les reins et la vessie; Prosta-Caps Chassot N; Tisane pour les reins et la vessie.

References

1Shibuya H et al. Indonesian medicinal plants. XXII. 1) Chemical structures of two new isopimarane-type diterpenes, orthosiphonones A and B, and a new benzochromene, orthochromene A from the leaves of Orthosiphon aristatus (Lamiaceae). Chem Pharm Bull 1999; 47: 695–698.

2 Guerin J-C, Reveillere H-P. Orthosiphon stamineus as a potent source of methylripariochromene A. J Nat Prod 1989; 52: 171–173.

3Ohashi K et al. Indonesian medicinal plants. XXIII. 1) Chemical structures of two new migrated pimarane-type diterpenes, neoorthosiphols A and B, and suppressive effects on rat thoracic aorta

of chemical constituents isolated from the leaves of Orthosiphon aristatus (Lamiaceae). Chem Pharm Bull 2000; 48: 433–435.

4Masuda T et al. Orthosiphol A and B, novel diterpenoid inhibitors of TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate)-induced inflammation,

from Orthosiphon stamineus. Tetrahedron 1992; 48: 6787–6792.

5 Stampoulis P et al. Staminol A, a novel diterpene from Orthosiphon stamineus. Tetrahedron Lett 1999; 40: 4239–4242.

6Shibuya H et al. Two novel migrated pimarane-type diterpenes, neoorthosiphols A and B, from the leaves of Orthosiphon aristatus (Lamiaceae). Chem Pharm Bull 1999; 47: 911–912.

7Awale S et al. Norstaminaneand isopimarane-type diterpenes of

Orthosiphon stamineus from Okinawa. Tetrahedron Lett 2002; 58:

5503–5512.

8 Awale S et al. Neoorthosiphonone A; a nitric oxide (NO) inhibitory diterpene with new carbon skeleton from Orthosiphon stamineus. Tetrahedron Lett 2004; 45: 1359–1362.

9Awale S et al. Secoorthosiphols A-C: three highly oxygenated secoisopimarane-type diterpenes from Orthosiphon stamineus.

Tetrahedron Lett 2002; 43: 1473–1475.

10Schut G, Zwaving JH. Content and composition of the essential oil of

Orthosiphon aristatus. Planta Med 1986; 52: 240–241.

11Lyckander IM, Malterud KE. Lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus as inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase. Acta Pharm Nord 1992; 4: 159–166.

12Schneider G, Tan HS. Die lipophilen Flavone von Folia Orthosiphonis.

Dtsch Apoth Ztg 1973; 113: 201.

13Sumaryono W et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the phenolic constituents from Orthosiphon aristatus. Planta Med 1991; 57: 176–180.

14Proksch P. Orthosiphon aristatus (Blume) Miquel—der Katzenbart. Pflanzeninhaltsstoffe und ihre potentielle diuretische Wirkung. Z Phytother 1992; 13: 63–69.

15Pietta PG et al. High-performance liquid chromatography with diodearray ultraviolet detection of methoxylated flavones in Orthosiphon leaves. J Chromatog 1991; 547: 439–442.

16Bombardelli E et al. Flavonoid constituents of Orthosiphon stamineus.

Fitoterapia 1972; 43: 35.

17Matsubara T et al. Antihypertensive actions of methylripariochromene A from Orthosiphon aristatus, an Indonesian traditional medicinal plant. Biol Pharm Bull 1999; 22: 1083–1088.

18Beaux D et al. Effect of extracts of Orthosiphon stamineus Benth,

Hieracium pilosella L., Sambucus nigra L., and Arctostaphylos uvaursi (L.) Spreng. in rats. Phytother Res 1998; 12: 498–501.

19Casadebaig-Lafon J. Elaboration d'extraits végétaux adsorbés, réalisation d'extraits secs d'Orthosiphon stamineus Benth. Pharm Acta Helv 1989; 64: 220–224.

20Englert J, Harnischfeger G. Diuretic action of aqueous Orthosiphon extract in rats. Planta Med 1992; 58: 237–238.

21Schut GA, Zwaving JH. Pharmacological investigation of some lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon aristatus. Fitoterapia 1993; 64: 99–102.

22Mariam A et al. Hypoglycaemic activity of the aqueous extract of

Orthosiphon stamineus. Fitoterapia 1996; 67: 465–468.

23Malterud KE et al. Flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus. Planta Med 1989; 55: 569–570.

24Estevez NA. Fractions of Orthosiphon stamineus Benth. leaves with antitumour activity. Preliminary results. Rev Cuba Farm 1980; 14: 21.

25Chen C-P et al. Screening of Taiwanese drugs for antibacterial activity against Steptococcus mutans. J Ethnopharmacol 1989; 27: 285–295.

26Guerin J-C, Reveillere H-P. Antifungal activity of plant extracts used in therapy. II. Study of 40 plant extracts against 9 fungi species. Ann Pharm Franc 1985; 43: 77–81.

27Lyckander IM, Malterud KE. Lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus prevent oxidative inactivation of 15-lipoxygenase.

Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1996; 54: 239–246.

28Du Dat D et al. Studies on the individual and combined diuretic effects of four Vietnamese traditional herbal remedies (Zea mays,

Java Tea |

385 |

Imperata cylindrica, Plantago major and Orthosiphon stamineus). J Ethnopharmacol 1992; 36: 225–231.

29Nirdnoy M, Muangman V. Effects of Folia orthosiphonis on urinary stone promoters and inhibitors. J Med Assoc Thailand 1991; 74: 319– 321.

30Tiktinsky OL, Bablumyan YA. The therapeutic effect of Java tea and Equisetum arvense in patients with uratic diathesis. Urol Nefrol 1983; 48: 47–50.

J