- •Contents

- •Preface to the Third Edition

- •About the Authors

- •How to Use Herbal Medicines

- •Introduction

- •General References

- •Agnus Castus

- •Agrimony

- •Alfalfa

- •Aloe Vera

- •Aloes

- •Angelica

- •Aniseed

- •Apricot

- •Arnica

- •Artichoke

- •Asafoetida

- •Avens

- •Bayberry

- •Bilberry

- •Bloodroot

- •Blue Flag

- •Bogbean

- •Boldo

- •Boneset

- •Borage

- •Broom

- •Buchu

- •Burdock

- •Burnet

- •Butterbur

- •Calamus

- •Calendula

- •Capsicum

- •Cascara

- •Cassia

- •Cat’s Claw

- •Celandine, Greater

- •Celery

- •Centaury

- •Cereus

- •Chamomile, German

- •Chamomile, Roman

- •Chaparral

- •Cinnamon

- •Clivers

- •Clove

- •Cohosh, Black

- •Cohosh, Blue

- •Cola

- •Coltsfoot

- •Comfrey

- •Corn Silk

- •Couchgrass

- •Cowslip

- •Cranberry

- •Damiana

- •Dandelion

- •Devil’s Claw

- •Drosera

- •Echinacea

- •Elder

- •Elecampane

- •Ephedra

- •Eucalyptus

- •Euphorbia

- •Evening Primrose

- •Eyebright

- •False Unicorn

- •Fenugreek

- •Feverfew

- •Figwort

- •Frangula

- •Fucus

- •Fumitory

- •Garlic

- •Gentian

- •Ginger

- •Ginkgo

- •Ginseng, Eleutherococcus

- •Ginseng, Panax

- •Golden Seal

- •Gravel Root

- •Ground Ivy

- •Guaiacum

- •Hawthorn

- •Holy Thistle

- •Hops

- •Horehound, Black

- •Horehound, White

- •Horse-chestnut

- •Horseradish

- •Hydrangea

- •Hydrocotyle

- •Ispaghula

- •Jamaica Dogwood

- •Java Tea

- •Juniper

- •Kava

- •Lady’s Slipper

- •Lemon Verbena

- •Liferoot

- •Lime Flower

- •Liquorice

- •Lobelia

- •Marshmallow

- •Meadowsweet

- •Melissa

- •Milk Thistle

- •Mistletoe

- •Motherwort

- •Myrrh

- •Nettle

- •Parsley

- •Parsley Piert

- •Passionflower

- •Pennyroyal

- •Pilewort

- •Plantain

- •Pleurisy Root

- •Pokeroot

- •Poplar

- •Prickly Ash, Northern

- •Prickly Ash, Southern

- •Pulsatilla

- •Quassia

- •Queen’s Delight

- •Raspberry

- •Red Clover

- •Rhodiola

- •Rhubarb

- •Rosemary

- •Sage

- •Sarsaparilla

- •Sassafras

- •Saw Palmetto

- •Scullcap

- •Senega

- •Senna

- •Shepherd’s Purse

- •Skunk Cabbage

- •Slippery Elm

- •Squill

- •St John’s Wort

- •Stone Root

- •Tansy

- •Thyme

- •Uva-Ursi

- •Valerian

- •Vervain

- •Wild Carrot

- •Wild Lettuce

- •Willow

- •Witch Hazel

- •Yarrow

- •Yellow Dock

- •Yucca

- •1 Potential Drug–Herb Interactions

- •4 Preparations Directory

- •5 Suppliers Directory

- •Index

Hydrocotyle

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

The chemistry of hydrocotyle is well studied and its pharmacological activity seems to be associated with the triterpenoid constituents. Documented preclinical studies support the herbal use of hydrocotyle as a dermatological agent although robust clinical studies are lacking. In view of the lack of toxicity data, excessive ingestion of hydrocotyle and use during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Species (Family)

Centella asiatica (L.) Urban (Apiaceae Umbelliferae)

Synonym(s)

Asiatic Pennywort, Centella, Gotu Kola, Hydrocotyle asiatica L., Hydrocotyle lurida Hance, Indian Pennywort, Indian Water Navelwort, Ji Xue Cao

Part(s) Used

Herb

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHP 1983(G7)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

WHO volume 1 1999(G63)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL (for external use only)(G37)

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General Reference G60.

Amino acids Alanine and serine (major components), aminobutyrate, aspartate, glutamate, histidine, lysine and threonine.(1) The root contains greater quantities than the herb.(1)

Flavonoids Quercetin, kaempferol and various glycosides.(2–4)

Terpenoids Triterpenes, asiaticoside, centelloside, madecassoside, brahmoside and brahminoside (saponin glycosides). Aglycones are referred to as hydrocotylegenin A–E;(5) compounds A–D are reported to be esters of the triterpene alcohol R1- barrigenol.(5, 6) Asiaticentoic acid, centellic acid, centoic acid and madecassic acid.

Volatile oils Various terpenoids including b-caryophyllene, trans- b-farnesene and germacrene D (sesquiterpenes) as major components, a-pinene and b-pinene. The major terpenoid is stated to be unidentified.

Other constituents Hydrocotylin (an alkaloid), vallerine (a bitter principle), fatty acids (e.g. linoleic acid, linolenic acid, lignocene, oleic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid), phytosterols (e.g. campesterol, sitosterol, stigmasterol),(7) resin and tannin.

The underground plant parts of hydrocotyle have been reported

to contain small quantities of at least 14 different polyacetyl- enes.(8–10)

Food Use

Hydrocotyle is not used in foods.

Herbal Use

Hydrocotyle is stated to possess mild diuretic, antirheumatic, |

H |

|

dermatological, peripheral vasodilator and vulnerary properties. |

||

Traditionally it has been used for rheumatic conditions, cutaneous |

|

|

affections, and by topical application, for indolent wounds, |

|

|

leprous ulcers, and cicatrisation after surgery.(G7, G64) |

|

|

Dosage |

|

|

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses |

|

|

recommended in standard herbal reference texts are given below. |

|

|

Dried leaf 0.6 g as an infusion three times daily.(G7) |

|

|

Figure 1 Selected constituents of hydrocotyle.

371

372 Hydrocotyle

Figure 2 Hydrocotyle (Centella asiatica).

HPharmacological Actions

In vitro and animal studies

The triterpenoids are regarded as the active principles in hydrocotyle.(7) Asiaticoside is reported to possess wound-healing

ability, by having a stimulating effect on the epidermis and promoting keratinisation.(11) Asiaticoside is thought to act by an

inhibitory action on the synthesis of collagen and mucopolysaccharides in connective tissue.(11)

Both asiaticoside and madecassoside are documented to be

anti-inflammatory, and the total saponin fraction is reported to be active in the carrageenan rat paw oedema test.(12)

In vivo studies in rats have shown that asiaticoside exhibits a

protective action against stress-induced gastric ulcers, following subcutaneous administration,(13) and accelerates the healing of chemical-induced duodenal ulcers, after oral administration.(14) It was thought that asiaticoside acted by increasing the ability of the rats to cope with a stressful situation, rather than via a local effect

on the mucosa.(13)

In vivo studies in mice and rats using brahmoside and brahminoside, by intraperitoneal injection, have shown a CNSdepressant effect.(15) The compounds were found to decrease motor activity, increase hexobarbitone sleeping time, slightly decrease body temperature, and were thought to act via a cholinergic mechanism.(15) A hypertensive effect in rats was also observed, but only following large doses.(15) In vitro studies with brahmoside and brahminoside indicated a relaxant effect on the rabbit duodenum and rat uterus, and an initial increase, followed by a decrease, in the amplitude and rate of contraction of the isolated rabbit heart.(15) Higher doses were found to cause cardiac

arrest, although subsequent intravenous administration in dogs caused no marked change in an ECG.(15)

Fresh plant juice is reported to be devoid of antibacterial activity,(16) although asiaticoside has been reported to be active versus Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus leprae and Entamoeba histolytica, and oxyasiaticoside was documented to be active against tubercle bacillus.(16, 17) The fresh plant juice is also stated not to exhibit antitumour or antiviral activities, but to

possess a moderate cytotoxic action in human ascites tumour cells.(16)

Clinical studies

Several studies describing the use of hydrocotyle to treat wounds and various skin disorders have been documented. However, these

studies have important methodological limitations and preclude definitive conclusions on the effects of hydrocotyle. Robust clinical studies are required. A cream containing a hydrocotyle extract was found to be effective in the treatment of psoriasis in seven patients to whom it was applied.(18) An aerosol preparation, containing a hydrocotyle extract, was reported to improve the healing in 19 of 25 wounds that had proved refractory to other forms of treatment.(11) A hydrocotyle extract containing asiaticoside (40%), asiatic acid (29–30%), madecassic acid (29–30%) and madasiatic acid (1%) was stated to be successful as both a preventive and curative treatment, when given to 227 patients with keloids or hypertrophic scars.(19) The effective dose in adults was reported to be between 60 and 90 mg. It was proposed that the triterpene constituents in the hydrocotyle extract act in a similar manner to cortisone, with respect to wound healing, and interfere with the metabolism of abnormal collagen.(19)

Pharmacokinetics There are only very limited data on the pharmacokinetics of constituents of hydrocotyle.

The triterpene constituents are reported to be metabolised primarily in the faeces in a period of 24–76 hours, with a small percentage metabolised via the kidneys.(19) An extract containing asiatic acid, madecassic acid, madasiatic acid and asiaticoside reached peak plasma concentrations in 2–4 hours, irrespective of whether it is administered in tablet, oily injection or ointment formulations.(19)

Side-effects, Toxicity

Clinical data

There is a lack of clinical research assessing the effects of hydrocotyle and rigorous randomised controlled clinical trials are required.

A burning sensation was reported by four of 20 patients during the period of application of an aerosol preparation containing hydrocotyle.(11) However, it is not clear whether other components in the formulation contributed to this reaction. Ingestion of

hydrocotyle is stated to have produced pruritus over the whole body.(G51)

Preclinical data

In vitro antifertility activity against human and rat sperm has been described for the total saponin fraction.(17) Asiaticoside and brahminoside are thought to be the active components, although no spermicidal or spermostatic action could be demonstrated for

Figure 3 Hydrocotyle – dried drug substance (herb).

the pure saponins.(17) A crude hydrocotyle extract has been reported to significantly reduce the fertility of female mice when administered orally.(10) No mechanism of action was investigated.

Teratogenicity studies in the rabbit have reported negative findings for a hydrocotyle extract containing asiatic acid, madecassic acid, madasiatic acid and asiaticoside.(19)

Contra-indications, Warnings

It is stated that hydrocotyle may produce photosensitisation.(G7)

Drug interactions None documented. However, the potential for preparations of hydrocotyle to interact with other medicines administered concurrently, particularly those with similar or opposing effects, should be considered. There is limited evidence from preclinical studies that brahmoside and brahminoside, constituents of hydrocotyle, have CNS depressant activity.(15)

Pregnancy and lactation Hydrocotyle is reputed to be an abortifacient and to affect the menstrual cycle.(G30) Relaxation of the isolated rat uterus has been documented for brahmoside and brahminoside.(15) Triterpene constituents have been reported to lack any teratological effects in rabbits.(19) However, in view of the lack of toxicity data, the use of hydrocotyle during pregnancy and lactation should be avoided.

Preparations

Proprietary single-ingredient preparations

Austria: Madecassol. Belgium: Madecassol. Brazil: CentellaVit. Chile: Celulase Plus; Celulase; Centabel; Escar T; Madecassol. France: Madecassol. Greece: Madecassol. Hong Kong: Madecassol. Italy: Centellase. Mexico: Madecassol. Portugal: Madecassol. Singapore: Centellase; Centica. Spain: Blastoestimulina. Venezuela: Litonate; Madecassol; Triffadiane.

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Celu-Atlas; Centella Queen Complex; Centella Queen Reductora; Centellase de Centella Queen; Centellase Gel; Clevosan; Clevosan; Clevosan; Estri-Atlas; Garcinol Max; Ginal Cent; Ginkan; Herbaccion Celfin; Lidersoft; Mailen; Moragen; No-Gras; Ovumix; Pentol; Redudiet; Vagicural Plus; Venoful; VNS 45. Australia: Extralife Leg-Care. Brazil: Composto Anticelulitico; Composto Emagrecedor; Derm'attive 10; Emagrevit. Chile: Celulase Con Neomicina; Cicapost; Dermaglos Plus; Escar T-Neomicina; Madecassol Neomicina. France: Calmiphase; Fadiamone; Madecassol Neomycine

Hydrocotyle 373

Hydrocortisone. Italy: Angioton; Angioton; Capill Venogel; Capill; Centella Complex; Centella Complex; Centeril H; Centeril H; Dermilia Flebozin; Emmenoiasi; Flebolider; Gelovis; Neomyrt Plus; Osmogel; Pik Gel; Varicofit; Venactive. Malaysia: Total Man. Mexico: Madecassol C; Madecassol N. Monaco: Akildia. Portugal: Antiestrias. Spain: Blastoestimulina; Blastoestimulina; Blastoestimulina; Cemalyt; Nesfare.

References

1George VK, Gnanarethinam JL. Free amino acids in Centella asiatica. Curr Sci 1975; 44: 790.

2 Rzadkowska-Bodalska H. Flavonoid compounds in herb pennywort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris). Herba Pol 1974; 20: 243–246.

3Voigt G et al. Zur Struktur der Flavonoide aus Hydrocotyle vulgaris L. Pharmazie 1981; 36: 377–379.

4 |

Hiller K et al. Isolierung von Quercetin-3-O-(6-O-a-L- |

|

|

arabinopyranosyl)-b-D-galaktopyranosid, einem neuen Flavonoid aus |

|

|

Hydrocotyle vulgaris L. Pharmazie 1979; 34: 192–193. |

H |

5 |

Hiller K et al. Saponins of Hydrocotyle vulgaris. Pharmazie 1971; 26: |

|

|

780. |

|

6Hiller K et al. Zur Struktur des Hauptsaponins aus Hydrocotyle vulgaris L. Pharmazie 1981; 36: 844–846.

7 Asakawa Y et al. Monoand sesquiterpenoids from Hydrocotyle and Centella species. Phytochemistry 1982; 21: 2590–2592.

8Bohlmann F, Zdero C. Polyacetylenic compounds. 230. A new polyyne from Centella species. Chem Ber 1975; 108: 511–514.

9 Schulte KE et al. Constituents of medical plants. XXVII. Polyacetylenes from Hydrocotyle asiatica. Arch Pharm (Weinheim)

1973; 306: 197–209.

10Gotu Kola. Lawrence Review of Natural Products, 1988.

11Morisset T et al. Evaluation of the healing activity of hydrocotyle tincture in the treatment of wounds. Phytother Res 1987; 1: 117–121.

12Jacker H-J et al. Zum antiexsudativen Verhalten einiger Triterpensaponine. Pharmazie 1982; 37: 380–382.

13Ravokatra A, Ratsimamanga AR. Action of a pentacyclic triterpenoid, asiaticoside, obtained from Hydrocotyle madagascariensis or Centella asiatica against gastric ulcers of the Wistar rat exposed to cold (28). C R Acad Sci (Paris) 1974; 278: 1743–1746.

14Ravokatra A et al. Action of asiaticoside extracted from hydrocyte on duodenal ulcers induced with mercaptoethylamine in male Wistar rats. C R Acad Sci (Paris) 1974; 278: 2317–2321.

15Ramaswamy AS et al. Pharmacological studies on Centella asiatica Linn. (Brahma manduki) (N.O. Umbelliferae). J Res Indian Med 1970; 4: 160–175.

16Lin Y-C et al. Search for biologically active substances in Taiwan medicinal plants. 1. Screening for anti-tumor and anti-microbial substances. Chin J Microbiol 1972; 5: 76–81.

17Oliver-Bever B. Medicinal Plants in Tropical West Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

18Natarajan S, Paily PP. Effect of topical Hydrocotyle asiatica in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol 1973; 18: 82–85.

19Bossé J-P et al. Clinical study of a new antikeloid agent. Ann Plast Surg 1979; 3: 13–21.

Ispaghula

Summary and Pharmaceutical Comment

The characteristic component of ispaghula is the mucilage which provides it with its bulk laxative action. Many of the herbal uses are therefore supported, although no published information was located to justify the use of ispaghula in cystitis or infective skin conditions. Adverse effects and precautions generally associated with bulk laxatives apply to ispaghula. Clinical evidence exists for hypocholesterolaemic activity.

The EMEA Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products

(HMPC) draft Community Herbal Monographs for ispaghula husk(G82) and seed(G83) include the following therapeutic

indications: (a) treatment of habitual constipation; (b)

Iconditions in which easy defecation with soft stools is desirable, e.g. in cases of painful defecation after rectal or anal surgery, anal fissures and haemorrhoids;(G82, G83) and for ispaghula husk, (c) in patients for whom an increased daily fibre intake may be advisable, e.g. as an adjuvant in

constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, and as an adjuvant to diet in hypercholesterolaemia.(G82) Bulk laxatives lower the transit time through the gastrointestinal tract and may affect the absorption of concurrently administered drugs. Concomitant use with thyroid hormones

and medicines known to inhibit peristalsis should only be under medical supervision.(G82, G83)

Ispaghula seed and husk may be used during pregnancy and lactation.

Species (Family)

Plantago ovata Forssk. (Plantaginaceae)

Synonym(s)

Blond Psyllium, Indian Plantago, Ispagol, Ispaghul, Pale Psyllium,

Spogel

Part(s) Used

Seed, husk

Pharmacopoeial and Other Monographs

BHC 1992(G6)

BHP 1996(G9)

BP 2007(G84)

Complete German Commission E (Psyllium, Blonde)(G3)

EMEA HMPC Community Herbal Monographs(G82, G83)

ESCOP 2003(G76)

Martindale 35th edition(G85)

Ph Eur 2007(G81)

WHO volume 1 1999(G63)

USP29/NF24(G86)

Legal Category (Licensed Products)

GSL(G37)

Constituents

The following is compiled from several sources, including General References G2, G6, G52 and G59.

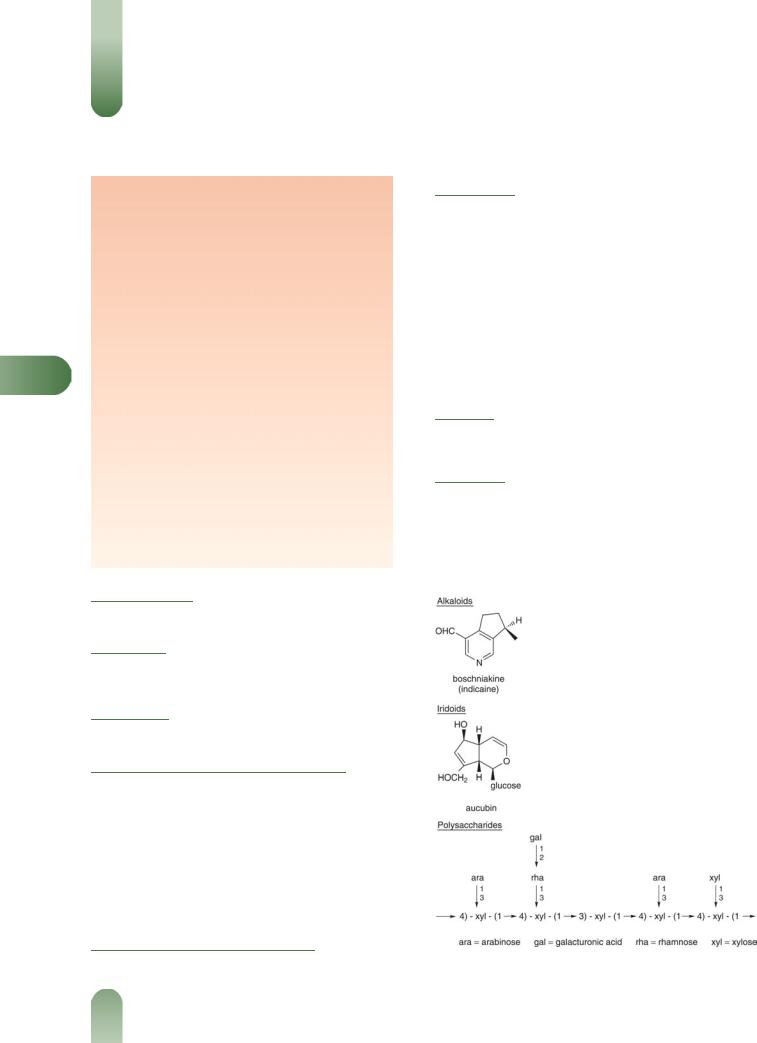

Alkaloids Monoterpene-type. (þ)-Boschniakine (indicaine), (þ)- boschniakinic acid (plantagonine) and indicainine.

Mucilages 10–30%. Mucopolysaccharide consisting mainly of a highly branched arabinoxylan with a xylan backbone and branches of arabinose, xylose and 2-O-(galacturonic)-rhamnose moieties. Present mainly in the seed husk.

Other constituents Aucubin (iridoid glucoside), sugars (fructose, glucose, sucrose), planteose (trisaccharide), protein, sterols (campesterol, b-sitosterol, stigmasterol), triterpenes (a- and b- amyrin), fatty acids (e.g. linoleic, oleic, palmitic, stearic), tannins.

Food Use

In food manufacture, ispaghula may be used as a thickener or stabiliser.(G41)

Herbal Use

Ispaghula is stated to possess demulcent and laxative properties. Traditionally, ispaghula has been used in the treatment of chronic

constipation, dysentery, diarrhoea and cystitis.(G2, G4, G6–G8, G32, G43, G52, G64) Topically, a poultice has been used for furunculosis.

The German Commission E approved use for chronic constipation and disorders in which bowel movements with loose stools are desirable, e.g. patients with anal fistulas, haemorrhoids, preg-

Figure 1 Selected constituents of ispaghula.

374

Figure 2 Ispaghula (Plantago ovata).

nancy, secondary medication in the treatment of various forms of diarrhoea and in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.(G3)

The European Medicines Agency (EMEA) Committee on

Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) has adopted a Community Herbal Monograph for ispaghula husk(G82) and seed.(G83) The

draft monographs include the following therapeutic indications under well-established use: (a) treatment of habitual constipation;

(b) conditions in which easy defaecation with soft stools is

desirable, e.g. in cases of painful defaecation after rectal or anal surgery, anal fissures and haemorrhoids;(G82, G83) and for ispa-

ghula husk, (c) in patients for whom an increased daily fibre intake may be advisable, e.g. as an adjuvant in constipationpredominant irritable bowel syndrome, and as an adjuvant to diet in hypercholesterolaemia.(G82)

Dosage

Dosages for oral administration (adults) for traditional uses recommended in older and contemporary standard herbal reference texts are given below.

Seeds 5–10 g (3 g in children) three times daily;(G6, G7) 12–40 g per day, husk 4–20 g;(G3) 3–5 g.(G43) Children 6–12 years, half adult

dose. Children under six years, treat only under medical supervision.(G52) Seeds should be soaked in warm water for

several hours before taking.

Liquid extract 2–4 mL (1 : 1 in 25% alcohol) three times

daily.(G6, G7)

Husk 3–5 g.(G46) Seeds and husk should be soaked in warm water for several hours before administration.

|

Ispaghula |

375 |

|

|

The EMEA HMPC Community Herbal Monographs advise the |

|

|||

following dosages. |

|

|

||

Ispaghula husk, indications (a) and (b) (see Herbal Use)(G82) |

|

|||

Adults, elderly, adolescents aged over 12 years: 7–11 g daily in |

|

|||

divided doses. Children aged 6–12 years: 3–8 g daily in divided |

|

|||

doses. |

|

|

||

Ispaghula husk, indication (c) (see Herbal Use)(G82) Adults, |

|

|||

elderly, adolescents aged over 12 years: 7–20 g daily in one to three |

|

|||

divided doses. |

|

|

||

Ispaghula seed, indications (a) and (b) (see Herbal Use)(G83) |

|

|||

Adults, elderly, adolescents aged over 12 years: 25–40 g daily in |

|

|||

one to three divided doses. Children aged 6–12 years: 12–25 g daily |

|

|||

in one to three divided doses. |

|

|

||

Pharmacological Actions |

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

The principal pharmacological actions of ispaghula can be |

|

|||

attributed to the mucilage component. |

|

|

||

In vitro and animal studies |

|

I |

||

An alcoholic extract lowered the blood pressure of anaesthetised |

||||

|

||||

cats and dogs, inhibited isolated rabbit and frog hearts, and |

|

|||

stimulated rabbit, rat and guinea-pig ileum.(G41) The extract |

|

|||

exhibited cholinergic activity.(G41) A mild laxative action has also |

|

|||

been reported in mice administered iridoid glycosides, including |

|

|||

aucubin.(1) Four-week supplementation of a fibre-free diet with |

|

|||

ispaghula seeds (100 or 200 g/kg) was compared with that of the |

|

|||

husks and wheat bran in rats.(2) The seeds increased faecal fresh |

|

|||

weight by up to 100% and faecal dry weight by up to 50%. Total |

|

|||

faecal bile acid secretion was stimulated, and b-glucuronidase |

|

|||

activity reduced, by ispaghula. The study concluded that ispaghula |

|

|||

acts as a partly fermentable, dietary fibre supplement increasing |

|

|||

stool bulk, and that it probably has metabolic and mucosa- |

|

|||

protective effects. |

|

|

||

Ispaghula husk depressed the growth of chickens by 15% when |

|

|||

added to their diet at 2%.(G41) |

|

|

||

Ispaghula seed powder is stated to have strongly counteracted |

|

|||

the deleterious effects of adding sodium cyclamate (2%), FD & C |

|

|||

Red No. 2 (2%), and polyoxyethylene sorbitan monostearate (4%) |

|

|||

to the diet of rats.(G41) |

|

|

||

Clinical studies |

|

|

||

Ispaghula is used as a bulk laxative.(G3, G43, G52) The |

swelling |

|

||

properties of the mucilage enable it to absorb water in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby increasing the volume of the faeces

Figure 3 Ispaghula – dried drug substance (seed).

376 Ispaghula

and promoting peristalsis. Bulk laxatives are often used for the treatment of chronic constipation and when excessive straining must be avoided following ano rectal surgery or in the management of haemorrhoids. Ispaghula is also used in the management of diarrhoea and for adjusting faecal consistency in patients with colostomies and in patients with diverticular disease or irritable bowel syndrome.

Laxative effect Ispaghula increases water content of stools and total stool weight in patients,(3) thus promoting peristalsis and reducing mouth-to-rectum transit time.(4) In a short-term study, 42 adults with constipation (43 bowel movements per week) received either ispaghula (7.2 g/day) or ispaghula plus senna (6.5 g þ 1.5 g/day).(5) Both treatments increased defecation frequency, and wet and dry stool weights, improved stool consistency, and gave subjective relief.

A randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, multicentre study involved 170 subjects with chronic idiopathic constipation.(6) The study included a two-week baseline (placebo) phase, followed by two weeks' treatment with ispaghula (Metamucil) 5.1 g, twice

Idaily or docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily. Compared with docusate, ispaghula significantly increased stool water content

(0.01% versus 2.33% for docusate and ispaghula, respectively; p = 0.007), and total stool output (271.9 g/week versus 359.9 g/week for docusate and ispaghula, respectively; p = 0.005). Furthermore, bowel movement frequency was significantly greater for ispaghula, compared with docusate. It was concluded that ispaghula has greater overall laxative efficacy than docusate in patients with chronic constipation.(6)

Antidiarrhoeal effect An open, randomised, crossover trial involving 25 patients with diarrhoea compared the effects of loperamide with those of ispaghula and calcium.(7) Nineteen patients completed both periods of treatment. The results indicated that both treatments halved stool frequency. Ispaghula and calcium were reported to be significantly better than loperamide with regard to urgency and stool consistency.(7)

Nine volunteers with phenolphthalein-induced diarrhoea were treated in random sequence with placebo, ispaghula (Konsyl), calcium polycarbophyl or wheat bran.(8) Wheat bran and calcium polycarbophyl had no effect on faecal consistency or on faecal viscosity. By contrast, ispaghula made stools firmer and increased faecal viscosity. In a dose–response study involving six subjects, 9, 18 and 30 g ispaghula per day caused a near-linear increase in faecal viscosity.(8)

The effects of ispaghula have been explored in children. In an open, uncontrolled study, 23 children with chronic non-specific diarrhoea were treated with an unrestricted diet for one week, and then treated with ispaghula (Metamucil) for two weeks (one tablespoonful twice daily). Seven patients responded to the unrestricted diet and 13 were said to respond to ispaghula treatment.(9)

Hypocholesterolaemic effects In a double-blind, placebocontrolled, parallel-group study, 26 men with mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolaemia (serum cholesterol concentration: 4.86– 8.12 mmol/L) received ispaghula (Metamucil) 3.4 g, or cellulose placebo, three times daily at meal times for eight weeks.(10) At the end of the study, serum cholesterol concentrations were reduced by 14.8% in the treated group, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by 20.2% and ratio of LDL to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol by 14.8%, compared with baseline values. There were no significant changes in serum lipid concentrations with placebo treatment, compared with baseline values. Differ-

ences in serum cholesterol concentrations between the two groups were statistically significant after four weeks (p-value not reported).

A double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel trial study compared the effects of ispaghula (Metamucil 5.1 g, daily) and placebo in 118 patients (aged 21–70 years old) with primary hypercholesterolaemia (total serum cholesterol 55.7 mmol/L).(11) Thirtyseven participants maintained a high-fat diet and 81 a low-fat diet. Treated patients in both lowand high-fat diet groups showed small significant decreases (p < 0.05) in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels (5.8% and 7.2%, respectively, for high-fat diets; 4.2% and 6.4%, respectively, for low-fat diets). No significant differences were seen in LDL cholesterol response for treated patients on either diet.

In a randomised, double-blind, crossover study, 20 males (mean (SD) age 44 (4) years) with moderate hypercholesterolaemia (mean (SD) total cholesterol concentration 265 (17) mg/ dL, LDL 184 (15) mg/dL) were randomised to receive a 40-day

course of ispaghula (Metamucil) 15 g daily, or placebo (cellulose).(12) There was a wash-out period of more than 10 days

between treatments. Ispaghula lowered LDL cholesterol (168 mg/ dL) more than did cellulose placebo (179 mg/dL), decreased relative cholesterol absorption, and increased the fractional turnover of both chenodeoxycholic acid and cholic acid. Bile acid synthesis increased in subjects whose LDL cholesterol was lowered by more than 10%. It was concluded that ispaghula lowers LDL cholesterol primarily by stimulation of bile acid synthesis.(12)

A meta-analysis of eight published and four unpublished studies carried out in four countries reviewed the effect of consumption of ispaghula-enriched cereal products on blood cholesterol, and LDL and HDL cholesterol concentrations.(13) Overall, the trials included 404 adults with mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolaemia (5.17–7.8 mmol/L) who consumed low-fat diets. The meta-analysis indicated that subjects who consumed ispaghula cereal had lower total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol than subjects who ate control cereal concentrations (differences of 0.31 mmol/L (5%) and 0.35 mmol/L (9%), respectively). HDL cholesterol concentrations were not affected in subjects eating ispaghula cereal.

Another meta-analysis included eight studies involving a total of 384 patients with hypercholesterolaemia who received ispaghula and 272 subjects who received cellulose placebo.(14) Compared with placebo, consumption of 10.2 g ispaghula per day for 58 weeks lowered serum total cholesterol concentrations by 4% (p < 0.0001) and LDL cholesterol by 7% (p < 0.0001), but did not affect serum HDL cholesterol or triacyl glycerol concentrations. The ratio of apolipoprotein (apo) B to apo A-1 was lowered by 6% (p < 0.05), relative to placebo, in subjects consuming a lowfat diet.(14) It was concluded that ispaghula is a useful adjunct to a low-fat diet in individuals with mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolaemia.

A randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study evaluated the long-term effectiveness of ispaghula husk as an adjunct to diet in treatment of primary hypercholesterolaemia.(15) Men and women with hypercholesterolaemia followed the American Heart Association Step 1 diet for eight weeks prior to treatment. Individuals with LDL cholesterol concentrations between 3.36 and 4.91 mmol/L were randomly assigned to receive either ispaghula (Metamucil 5.1 g) or cellulose placebo twice daily for 26 weeks whilst continuing diet therapy. Overall, 163 participants completed the full protocol, 133 receiving ispaghula and 30 receiving cellulose placebo. Serum total and LDL cholesterol concentrations

were 4.7% and 6.7% lower, respectively, in the ispaghula group than in the placebo group after 24–26 weeks (p < 0.001).

A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial assessed the effects of ispaghula in lowering elevated LDL cholesterol concentrations in 20 children (aged 5–17 years).(16) Children with LDL cholesterol concentrations of >2.84 mmol/L after three months on a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet received five weeks' treatment with a ready-to-eat cereal containing watersoluble ispaghula husk (6 g/day) or placebo. The results indicated that there were no significant differences in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol or HDL cholesterol concentrations between the two groups.

In a similar 12-week study, 50 children (aged 2–11 years) with LDL cholesterol concentrations 5110 mg/dL received either cereal enriched with ispaghula (3.2 g soluble fibre per day) or plain cereal whilst maintaining a low-fat diet.(17) Total cholesterol decreased by 21 mg/dL for the ispaghula group in comparison with 11.5 mg/ dL for the control group (p < 0.001). LDL cholesterol also decreased by 23 mg/dL for the treated group in comparison with 8.5 mg/dL for the placebo group (p < 0.01).

The effect of adding water-soluble fibre to a diet low in total fats, saturated fat and cholesterol to treat hypercholesterolaemic children and adolescents has been reviewed.(18) The review summarised that reductions in LDL cholesterol concentrations ranged from 0–23%. This wide range may be related to dietary intervention and to clinical trial conditions. It was proposed that additional trials with larger numbers of well-defined subjects are needed.

Hypoglycaemic effect Several studies have shown that ispaghula husk lowered blood glucose concentrations due to delayed intestinal absorption.(G52) In one crossover study, 18 patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes received ispaghula (Metamucil) or placebo twice (immediately before breakfast and dinner) during each 15-hour crossover phase.(19) For meals eaten immediately after ispaghula ingestion, maximum postprandial glucose elevation was reduced by 14% at breakfast and 20% at dinner, relative to placebo. Postprandial serum insulin concentrations measured after breakfast were reduced by 12%, relative to placebo. Second-meal effects after lunch showed a 31% reduction in postprandial glucose elevation, relative to placebo. No significant differences in effects were noted between patients whose diabetes was controlled by diet alone and those whose diabetes was controlled by oral hypoglycaemic drugs. It was concluded that the results indicate that ispaghula as a meal supplement reduces proximate and second-meal postprandial glucose and insulin in non-insulin dependent diabetics.(19)

Other effects Ispaghula husk has been used to treat small numbers of patients with left-sided diverticular disease.(4) Marked motility was observed for the right colon, but was not as pronounced for the left colon. The effects of ispaghula in this condition may be worth further investigation.

In an open, randomised, multicentre trial, 102 patients with ulcerative colitis (three months in remission, salicylate-treated, colitis over 20 cm) received ispaghula (10 g twice daily; n = 35), oral mesalazine (500 mg three times daily; n = 37) or ispaghula plus mesalazine (n = 30) for one year.(20) Assessment, including endoscopy, was carried out at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. The results suggested that ispaghula may be equivalent to mesalazine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. However, this requires further investigation in a randomised, double-blind study.

Ispaghula |

377 |

Side-effects, Toxicity

In common with all bulk laxatives, ispaghula seed and husk may increase or cause flatulence, although this usually disappears in the course of treatment. There is a risk of abdominal distension and intestinal or oesophageal obstruction, particularly if ispaghula seed or husk is swallowed dry or without sufficient fluid.

Allergic reactions, including (rarely) anaphylactic reactions, may

occur.(G3, G83, G84)

Contra-indications, Warnings

The EMEA HMPC Community Herbal Monographs include the |

|

following information. Ispaghula seed and husk should not be |

|

used by patients with: a sudden change in bowel habit that persists |

|

for more than two weeks; undiagnosed rectal bleeding; failure to |

|

defecate following the use of a laxative; abnormal constrictions in |

|

the gastrointestinal tract; diseases of the oesophagus and cardia; |

|

potential or existing intestinal blockage (ileus); paralysis of the |

|

intestine or megacolon; poorly controlled diabetes mellitus; |

I |

known hypersensitivity to ispaghula seed or husk.(G82, G83) |

|

Ispaghula seed and husk should not be used by patients with |

|

faecal impaction and undiagnosed abdominal symptoms, abdom- |

|

inal pain, nausea and vomiting (unless advised by a doctor).(G82) |

|

Where ispaghula seed or husk is used in constipation, the use of |

|

ispaghula husk should be discontinued and medical advice sought |

|

if the constipation does not resolve within three days of starting |

|

treatment, if abdominal pain occurs and/or if there is any |

|

irregularity in the faeces. Where ispaghula seed or husk is used as |

|

an adjuvant to diet in hypercholesterolaemia this should be under |

|

medical supervision.(G82) Ispaghula seed and ispaghula husk |

|

should always be taken with a sufficient amount of fluid: for |

|

each 1 g of the herbal substance, at least 30 mL of fluid (water, |

|

milk or fruit juice) should be used to prepare a mixture. Taking |

|

these preparations without adequate fluid may cause them to swell |

|

and block the throat or oesophagus and may cause choking. |

|

Intestinal obstructions may occur if an adequate fluid intake is not |

|

maintained. Ispaghula should not be taken by anyone who has had |

|

difficulty in swallowing or any throat problems. If chest pain, |

|

vomiting or difficulty in swallowing or breathing is experienced |

|

after taking the preparation, immediate medical attention should |

|

be sought. The treatment of the debilitated patient requires |

|

medical supervision. The treatment of elderly patients should be |

|

supervised. Preparations of ispaghula seed and ispaghula husk |

|

should be taken during the day and at least 30 minutes away from |

|

intake of other medicines.(G82, G83) |

|

Drug and other interactions Bulk laxatives lower the transit |

|

time through the gastrointestinal tract and therefore may affect |

|

the absorption of other drugs.(G45) Absorption of concurrently |

|

administered drugs may be delayed. The EMEA HMPC Commu- |

|

nity Herbal Monographs include the following information. |

|

Enteral absorption of concomitantly administered medicines |

|

such as minerals (e.g. calcium, iron, lithium, zinc), vitamins |

|

(B12), cardiac glycosides and coumarin derivatives may be delayed. |

|

For this reason the product should not be taken within 0.5–1 hour |

|

of other medicines. If the product is taken together with meals in |

|

the case of insulin-dependent diabetics, it may be necessary to |

|

reduce the insulin dose. Ispaghula seed and husk should only be |

|

used concomitantly with thyroid hormones under medical super- |

|

vision as the dose of thyroid hormones may need to be adjusted. |

|

In order to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal obstruction, |

|

ispaghula seed and husk should only be used with medicines |

|

378 Ispaghula

known to inhibit peristalsis (e.g. loperamide, opioids and opioidlike agents) under medical supervision.(G82, G83)

Pregnancy and lactation Ispaghula seed and husk may be used during pregnancy and lactation.

Preparations

Proprietary single-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Agiofibras; Konsyl; Lostamucil; Metamucil; Motional; Mucofalk; Plantaben. Australia: Agiofibe; Ford Fibre; Fybogel; Metamucil. Austria: Agiocur; Laxans; Metamucil. Belgium: Colofiber. Brazil: Agiofibra; Metamucil; Plantaben. Canada: Laxucil; Metamucil; Mucillium; NovoMucilax; Prodiem Plain. Chile: Euromucil; Fibrasol; Metamucil; Plantaben. Denmark: Vi-Siblin. Finland: Agiocur; Laxamucil; Vi-Siblin. France: Mucivital; Spagulax Mucilage; Spagulax; Transilane. Germany: Agiocur; Flosa; Flosine;

IMetamucil; Mucofalk; Naturlax. India: Isogel. Ireland: Fybogel. Israel: Agiocur; Konsyl; Mucivital. Italy: Agiofibre; Fibrolax; Planten. Malaysia: Mucofalk. Mexico: Agiofibra; Fibromucil; Hormolax; Metamucil; Mucilag; Plantaben; Siludane. Monaco: Psylia. Netherlands: Metamucil; Mucofalk; Regucol; Volcolon. Norway: Lunelax; Vi-Siblin. New Zealand: Isogel; Metamucil; Mucilax. Portugal: Agiocur; Mucofalk. South Africa: Agiobulk; Agiogel; Fybogel. Singapore: Fybogel; Mucilin; Mucofalk. Spain: Biolid; Cenat; Laxabene; Metamucil; Plantaben. Sweden: Lunelax; Vi-Siblin. Switzerland: Agiolax mite; Laxiplant Soft; Metamucil; Mucilar. Thailand: Agiocur; Fybogel; Metamucil; Mucilin. UK: Fibrelief; Fybogel; Isogel; Ispagel; Regulan. USA: Fiberall; Hydrocil Instant; Konsyl-D; Konsyl; Metamucil; Reguloid; Syllact.

Proprietary multi-ingredient preparations

Argentina: Agiolax; Isalax Fibras; Kronolax; Medilaxan; Mermelax; Rapilax Fibras; Salutaris. Australia: Agiolax; Bioglan Psylli-Mucil Plus; Herbal Cleanse; Nucolox; PC Regulax. Austria: Agiolax. Belgium: Agiolax. Brazil: Agiolax; Plantax. Canada: Prodiem Plus. Chile: Bilaxil. Finland: Agiolax. France: Agiolax; Filigel; Imegul; Jouvence de l'Abbe Soury; Parapsyllium; Schoum; Spagulax au Citrate de Potassium; Spagulax au Sorbitol. Germany: Agiolax. Hong Kong: Agiolax. Ireland: Fybogel Mebeverine. Israel: Agiolax. Italy: Agiolax; Duolaxan; Fibrolax Complex; Sedatol; Sedatol; Soluzione Schoum. Mexico: Agiolax. Netherlands: Agiolax.

Norway: Agiolax. Portugal: Agiolax; Excess. South Africa:

Agiolax. Spain: Agiolax; Solucion Schoum. Sweden: Agiolax; Vi-Siblin S. Switzerland: Agiolax; Mucilar Avena. Thailand: Agiolax. UK: Anased; Fibre Dophilus; Fibre Plus; Fybogel Mebeverine; HRI Calm Life; Manevac; Nodoff; Nytol Herbal;

Slumber. USA: Perdiem; Senna Prompt. Venezuela: Agiolax; Avensyl; Fiberfull; Fibralax; Senokot con Fibra.Metamucil; Mucofalk; Pascomucil. Hong Kong: Agiocur;

References

1 Inouye H et al. Purgative activities of iridoid glycosides. Planta Med 1974; 25: 285–288.

2Leng-Peschlow E. Plantago ovata seeds as dietary fibre supplement: physiological and metabolic effects in rats. Br J Nutr 1991; 66: 331–

349.

3Stevens J et al. Comparison of the effects of psyllium and wheat bran on gastrointestinal transit time and stool characteristics. J Am Diet

Assoc 1988; 88: 323–326.

4 Thorburn HA et al. Does ispaghula husk stimulate the entire colon in diverticular disease? Gut 1992; 33: 352–356.

5Marlett JA et al. Comparative laxation of psyllium with and without senna in an ambulatory constipated population. Am J Gastroenterol

1987; 82: 333–337.

6McRorie JW et al. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 491–497.

7 Qvitzau S et al. Treatment of chronic diarrhoea: loperamide versus ispaghula husk and calcium. Scand J Gastroenterol 1988; 23: 1237– 1240.

8Eherer AJ et al. Effect of psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and wheat bran on secretory diarrhea induced by phenolphthalein. Gastroenterology 1993; 104: 1007–1012.

9Smalley JR et al. Use of psyllium in the management of chronic nonspecific diarrhea of childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1982;

1: 361–363.

10Anderson JW et al. Cholesterol-lowering effects of psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid for hypercholesterolemic men. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148: 292–296.

11Sprecher DL et al. Efficacy of psyllium in reducing serum cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic patients on highor low-fat diets. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 545–554.

12Everson GT et al. Effects of psyllium hydrophilic mucilloid on LDLcholesterol and bile acid synthesis in hypercholesterolemic men. J Lipid Res 1992; 33: 1183–1192.

13Olson BH et al. Psyllium-enriched cereals lower blood total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, but not HDL cholesterol, in hypercholesterolemic adults: results of a meta-analysis. J Nutr 1997; 127: 1973–1980.

14Anderson JW et al. Cholesterol-lowering effects of psyllium intake adjunctive to diet therapy in men and women with hypercholesterolemia: meta-analysis of 8 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71: 472–479.

15Anderson JW et al. Long-term cholesterol-lowering effects of psyllium as an adjunct to diet therapy in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Am J Clin Nut 2000; 71: 1433–1438.

16Dennison BA, Levine DM. Randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, two-period crossover clinical trial of psyllium fiber in children with hypercholesterolemia. J Pediatr 1993; 123: 24–29.

17Williams CL et al. Soluble fiber enhances the hypocholesterolemic effect of the step I diet in childhood. J Am College Nutr 1995; 14: 251– 257.

18Kwiterovich Jr PO. The role of fiber in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1995; 96: 1005–1009.

19Pastors JG et al. Psyllium fiber reduces rise in postprandrial glucose and insulin concentrations in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 1991; 53: 1431–1435.

20Fernández-Bañares F et al. Randomised clinical trial of Plantago ovata efficacy as compared to mesalazine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: A971.